Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 7:10 AM

Study Session 6 Land Use and Urban Planning

Introduction

This is the second study session that looks at the growing trend for people to live in urban rather than rural areas. Study Session 5 described the main causes and effects of urbanisation. In this study session we will review how urbanisation changes the nature of the land surface and the consequences of that change. We will then consider the role of urban planning in reducing some of the negative effects of urbanisation and look at current urban development in Ethiopia.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 6

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

6.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3)

6.2 Explain the connections between land use and the physical environment. (SAQ 6.1)

6.3 Summarise the problems created by uncontrolled urban developments. (SAQ 6.2)

6.4 Describe how urban planning can contribute to sustainable urban living. (SAQ 6.4)

6.5 Summarise the achievements and challenges of the Integrated Housing Development Programme. (SAQ 6.5)

6.1 Change of land use

We depend on land to provide many essential life-supporting systems.

Think back through the previous study sessions and consider the different ways that we all use land. What different types of land use can you think of?

We use the land to provide food from agricultural activities; to supply wood from trees for construction and fuel; for water which is extracted from rivers and lakes on the land’s surface or from underground, and to provide rocks and building materials.

You may also have thought of the land that is used when we build houses, shops, factories, roads and other components that make up the urban environment. This is the aspect of land use that we will be focusing on in this study session.

Land use can be defined as arrangements, activities and inputs by people to produce, change or maintain a certain land cover type (FAO/UNEP, 1999). This definition makes it clear that there is a link between land use and land cover. Land cover is the observed biophysical cover on the Earth's surface. In non-urban areas land cover is usually described by the dominant vegetation type, such as forest, grassland or cropland. Changing the way the land is used (for example by building towns and cities on it) changes the land cover and has many direct and indirect effects.

Most consequences of changing land use through urbanisation can be grouped into two main categories: the decrease in natural and agricultural land, and the increase in hard surfaces of built-up areas.

6.1.1 Decrease in natural and agricultural land

Change from non-urban to urban land use causes the loss of many different types of vegetated land cover. This may be grassland used for grazing animals, cultivated fields that produce food and other crops, uncultivated areas of river banks and hillsides, and wooded areas covered with trees. Deforestation was discussed in Study Session 1 as one of the negative impacts of human use of resources.

What are the main negative effects of deforestation?

Deforestation can reduce the infiltration of water into the soil and groundwater, which can lower the water table and increase the volume and speed of surface run-off; if this happens it can increase soil erosion because the land surface is exposed. Deforestation also results in a loss of wildlife habitat and a reduction in biodiversity; and the loss of ecological services provided by trees (such as converting atmospheric carbon dioxide to oxygen by photosynthesis). You may also have mentioned the loss of the aesthetic value of trees, which are attractive elements in our biophysical environment.

The reduction in agricultural land also shifts the balance in the land area available for food production. The most productive land for agriculture tends to be near to towns. When towns expand this land gets covered with buildings and so it is no longer available for food production. This means there is less productive land available to meet the increasing demands for food from a growing urban population. The additional demands for food production in the areas around towns and cities can encourage the increased use of pesticides and fertilisers to improve productivity, which can have negative environmental impacts. It also encourages the cultivation of previously unused land such as sloping hillsides which, when ploughed, are extremely vulnerable to soil erosion when it rains.

6.1.2 Increased area of hard surfaces

The construction of urban areas increases the area of hard surfaces such as roofs, roads, and pavements. Unlike the natural land cover they replace, these hard surfaces are impermeable, meaning water cannot pass through them. When rain falls it does not infiltrate into soil and groundwater but instead pours off the surface very quickly. Water collects in gutters and drains and flows directly into rivers and ditches, which rapidly fill up and can overflow. The volume and speed of the flow of run-off leads to frequent flooding in many city areas (Figure 6.1). These problems are made even worse if there is no drainage system or if drainage is inadequate or becomes blocked with rubbish.

In addition to the effect on the water cycle, the increase in hard surface area also influences the exchange of energy with the atmosphere, which can lead to localised changes to the weather and climate. In large cities the temperature can be a few degrees warmer than in surrounding rural areas, an effect known as an urban heat island. This is caused by the hard surfaces of roads and buildings, which absorb energy from the sun and radiate heat into the surrounding air to a much greater extent than natural vegetated surfaces, especially at night. The raised temperature can increase the impact of poor air quality on people’s health.

6.1.3 Extraction of building materials

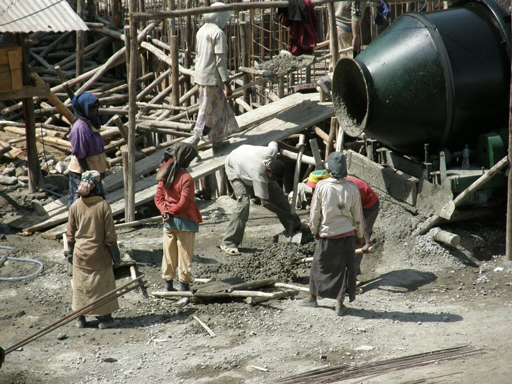

A third category of changed land use is the extraction of rocks and minerals for the construction industry (Figure 6.2). This process results in the loss of vegetated land cover where the rocks are extracted. Most of this resource extraction takes place in peri-urban areas because they are located conveniently close to the construction sites to minimise transport costs and time. Many small-scale, unregulated and low-technology extraction activities can be seen on sites around towns in Ethiopia.

These impacts of change in land use from rural to urban, combined with the effects that you read about in Study Session 5, add up to a lengthy list of negative consequences from urbanisation. Managing and minimising these effects is one of the main purposes of urban planning.

6.2 What is urban planning?

Urban planning is about designing towns and cities to function effectively and meet the needs of people living in them. This is a technical process, concerned with bringing benefits to people, controlling the use of land and enriching the natural environment. It requires careful assessment and planning so that community needs such as housing, environmental protection, health care and other infrastructure can be incorporated.

Urban planning means managing urban development so that uncontrolled and haphazard building is prevented. Unplanned development in peri-urban areas can lead to towns and cities spreading out and extending the impacts of change of land use over an ever-increasing area. In central urban areas, unplanned development gives rise to densely-packed, single-storey housing with narrow alleys making it very difficult to provide necessary services for the inhabitants (Figure 6.3). The negative effects of impoverished, informal settlements were described in Study Session 5.

What are the main negative impacts of slum areas on the people who live there?

The main problems are the poor quality of housing construction materials, overcrowding, and limited access to water and sanitation, which combine to create unhealthy living conditions.

Unplanned urban development is characterised by poor housing quality and by the lack of supporting infrastructure and services. These inadequate services can include any or all of: electricity, water supply, sanitation, drainage, solid waste management, roads and transport facilities, shops and schools and health care. The lack of available space in central urban areas also results in people building insecure homes in unsafe places, as shown in Figure 6.4. Urban planning aims to address these problems.

Historically, the concept of urban planning arose in Europe in the 19th century (Corburn, 2005). It emerged from the awareness that public health and infectious disease outbreaks were closely related to inadequate housing and poor sanitation, particularly affecting the urban poor. By the 20th century, the idea of land-use zoning was the dominant approach to urban planning. Zoning meant the creation of defined areas within a town that were designated for different activities such as residential, commerce, industry, etc. The aim was to improve urban living conditions by separating people from ‘noxious land uses’ (Corburn, 2005). However, zoning also had the effect of creating a social divide by separating areas where well-off people lived from those occupied by people with little or no income, with increasing inequality between the services and facilities available in different zones. Excluding people from living in central zones that were allocated for commerce and business resulted in increasing urban sprawl, where the effects of urbanisation and land-use change were spread over larger areas (UN-Habitat, n.d. 1). Recommended urban planning practice has since moved away from the zoning approach and currently adopts principles of integrated use designed to ensure the sustainability of future towns and cities.

6.3 Planning for sustainability

You could say that the purpose of urban planning is to manage land use so that it is sustainable. This means it should bring economic benefits, with social equity and without causing environmental harm. The promotion of ‘socially and environmentally sustainable human settlements development’ is part of the mission of UN-Habitat, the United Nations programme that is ‘working towards a better urban future’ (UN-Habitat, n.d. 2). They set out five principles for urban planning, shown in Box 6.1 (UN-Habitat, n.d. 1).

Box 6.1 UN-Habitat’s five principles for sustainable neighbourhood planning

The UN-Habitat approach to urban planning is based on three key features of sustainable neighbourhoods and cities, which are that they should be compact, integrated and connected. Five principles support these three features:

- Adequate space for streets and an efficient street network.

- High density of people: at least 15,000 people per km2.

- Mixed land use: housing mixed with business and other economic uses.

- Social mix: houses in different price ranges and tenures (rented, owned etc.) in any given area.

- Limited land-use specialisation: large areas should not be allocated for a single function.

In contrast with the zoning approach, these five principles emphasise the need for mixed land use developments that integrate different functions of residential, commercial and business together. Ideally, urban plans should mix housing with employment opportunities and include schools, shops and health care facilities. An adequate street network will allow access for cars, public transport and service vehicles. Plans should also consider the need for space for places of worship and for entertainment and leisure. Incorporating this diverse range of requirements for the urban environment is challenging. To be successful and sustainable, urban plans should ideally be developed with the participation of the people who will be living and working in the area. Meeting these expectations also requires significant economic resources, an effective decision-making and regulatory framework, and good governance.

We will now consider in a little more detail some aspects of sustainable urban planning that are particularly relevant to WASH, the environment and health, but are typically absent from unplanned developments. These are: housing quality; the infrastructure related to water, sanitation and solid wastes management; drainage systems; and green spaces.

6.3.1 Housing quality

One of the key elements to address health problems in poor urban areas is the quality of housing construction. Houses must be built with materials that are waterproof and durable, using appropriate construction techniques and following correct procedures. Regulatory systems need to be in place to ensure that buildings are constructed to a specified standard and monitoring procedures should be established to ensure compliance. However, the affordability of housing also needs to be considered. A research study found that the majority of households in Addis Ababa were unable to afford to build dwellings that met the standards set in 1994 and 2003 (Bihon, n.d.).

6.3.2 Infrastructure for water, sanitation and solid waste management

If you were planning a new water supply system for a town the first thing you would need to consider would be the source of water. (Some aspects of water source selection were discussed in Study Session 4.) Key questions include: Will there be enough water to meet the needs of the people living in the town? Will there be enough to meet future demand, say for the next 10 or 20 years? Is the quality of water acceptable? What water treatment will be needed to ensure the water is safe to drink? How far is the source from the town? And how will the water be moved from the source to users? Answering these questions is a complex technical process requiring models and calculations based on the number of people using the supply, expected use for non-domestic purposes, future expansion and growth, and geographical and hydrological survey data. In addition, for a piped water supply system, the infrastructure plan would include details of the network of water mains that deliver water to the users, with the layout of pipes and pumps required to distribute water to the new buildings.

Planning for sanitation is frequently neglected in urban plans. Sanitation services often focus on providing latrines and toilets but they do not give adequate attention to what happens next and how the waste is disposed of. Where houses are provided with piped water supplies and have water-flushed toilets, the most appropriate solution is a network of sewers to collect and transport the wastewater to a sewage treatment works. This is obviously a major undertaking at significant financial cost. In the absence of sewers, septic tanks are commonly used. Septic tanks are underground tanks into which sewage is piped. The wastewater remains in the tank for long enough for the solids to settle out as sludge and the liquid part is discharged from the tank, usually into the surrounding soil. The size of septic tank required is determined by the number of people using it. In heavily-populated urban areas, septic tanks are not ideal because there is limited space to accommodate the size and number of tanks required.

Where septic tanks and pit latrines are used, they need to be accessible for emptying (Figure 6.5). Sludge builds up in the tanks and pits and has to be removed on a regular basis. Faecal sludge management is a neglected area of urban planning. It requires systems to be in place for emptying the pits and tanks and transporting the sludge to an appropriate treatment plant or disposal site, away from the inhabited areas.

Urban plans also need to consider solid waste management. All sorts of wastes are indiscriminately discarded in towns and cities from homes, businesses and industry. Establishing systems to collect and manage the waste is a significant challenge, but urban planners can contribute by ensuring that the streets they design are wide enough to accommodate collection vehicles and that sites are identified for waste handling and disposal.

6.3.3 Drainage systems

Minimising the risk of flooding by designing effective drainage systems is another important aspect of urban plans. This is partly a matter of designing and building drains that are large enough to cope with high volumes of water. Rainwater from roofs can be collected and put to good use rather than just allowed to run into the drains. There are also ways of reducing the area of impermeable hard-surfacing so that more water can infiltrate into the ground and the speed and volume of surface run-off is reduced. These sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) include a range of techniques such as using gravel or cobblestones, which are permeable, rather than solid concrete, leaving grass or bare earth areas where possible so that water can infiltrate into the ground, and building ponds or water-holding areas into the drainage system so that rainwater is temporarily contained and the speed of flow is reduced.

6.3.4 Green spaces

Parks and other green spaces are important components of the urban environment for several reasons. Firstly, they are pleasant and enjoyable places to visit, offering a peaceful respite from busy city life (Figure 6.6). They provide areas of natural ground which absorb run-off and assist in the problems of surface water drainage. They also have a measurable cooling effect and can reduce the impact of the urban heat island. Feyisa et al. (2014) studied parks in Addis Ababa and found that the temperature inside the parks was as much as 6.7 ºC cooler than in the surrounding city.

6.4 Urban planning in Ethiopia

In the past the development of urban areas has received less attention than the rural and agricultural sector in Ethiopia (Ayenew, 2008). In combination with the significant challenges of urban poverty, this has allowed unplanned urban development and the growth of slum areas with undeveloped services and the associated social, health and environmental problems. In response to these challenges the government devised a National Urban Development Policy.

6.4.1 National Urban Development Policy

The National Urban Development Policy was approved in 2005 (Ayenew, 2008). It has two main packages: the Urban Development Package and the Urban Good Governance Package. The Urban Development Package set out the answer to the question ‘what’ was the government going to do to deliver urban-based public services of ‘jobs, houses, roads, schools, clinics, water supply etc.’? (MWUD, 2007). The Urban Good Governance Package set out how they would deliver these and other services with ‘efficiency, effectiveness, accountability, transparency, participation, sustainability, the rule of law, equity, democratic government and security’ (ibid).

The Urban Development Package includes five programmes, one of which is the Integrated Housing Development Programme.

6.4.2 Integrated Housing Development Programme

The Integrated Housing Development Programme (IHDP) is a government-led programme to provide new, affordable housing for low- and middle-income people. The programme began in 2005 and has been implemented in 56 towns across the country to date, but the greatest impact has been seen in Addis Ababa, where new condominium blocks are springing up all over the city (Cities Alliance, 2012) (Figure 6.7). Outside the capital the programme has since been suspended, partly because the multi-storey condominiums were unpopular and considered ‘an eyesore’ in smaller, low-rise towns (UN-Habitat, 2011).

The IHDP aimed to construct 360,000 new housing units in condominium blocks, to be built at low cost, plus 9000 commercial units, with the creation of 200,000 jobs and promotion of 10,000 small enterprises in the construction industry (UN-Habitat, 2011).

The standard design of IHDP condominium has five storeys, with a mixture of studios and 1-, 2- and 3-bedroom apartments. Each unit has a bathroom with shower, flush toilet, and basin, and a separate kitchen. The units are sold, not rented, and are transferred to owners by a computer-based lottery system. Owners have to pay a down payment. For studios and 1-bedroom units this is 10% of the price, for 2-bedroom units it is 20%, and for 3-bedroom units 40%. The remainder is paid by monthly mortgage payments with interest. Thirty per cent of units are allocated to women.

By 2011, 171,000 units had been built (UN-Habitat, 2011). The programme has been very popular and demand has exceeded supply from the outset. Its main achievements are a dramatic increase in the number of homeowners and an improvement in the living conditions of many thousands of people. In addition, the programme has created 176,000 jobs, mainly for mineral extraction and construction workers (Cities Alliance, 2012).

Despite these successes, a number of problems have arisen. Electricity and water companies have been slow to provide essential services because they lack the resources to meet the new demands. Approximately 50% of condominium sites are behind schedule because of delays with the infrastructure. The absence of a sewerage network is an obvious problem (only 3% of Addis Ababa is sewered) (UN-Habitat, 2011). Solid waste management is a more positive story, however, with opportunities for small enterprises to set up and organise door-to-door collection services.

The initial designs for the condominium sites included green spaces, but this idea was dropped when the housing density had to be increased. The sites had allocated spaces for commercial use, such as shops, food and drink outlets. There were also plans for communal buildings for social activities, but where these were built, the continuing management has been problematic. On other sites the communal buildings were not built, in order to reduce costs.

Affordability is a major issue. The costs put the units beyond the reach of many people on low incomes. Many people who have managed to make the initial down payment find that the monthly payments are too much, so they rent out all or part of the unit to other people. This has the unforeseen benefit of increasing the supply of rental housing in the city, but if people decide to share their unit this can result in overcrowded conditions. The higher down payment for the larger units can also cause overcrowding because families opt for a smaller unit than they need to reduce the initial cost.

Most building so far has been on the edges of Addis Ababa in areas with little or no employment opportunities. This forces people to travel into the city for work, which is costly for them and adds to the pressures on the transport system. There has also been criticism of the construction quality and the design of some of the blocks. The ongoing management of the sites, especially the shared areas, is also essential for the long-term sustainability of the programme (UN-Habitat, 2011).

What aspects of the IHDP’s condominium sites do and do not correspond to UN-Habitat’s principles for sustainable neighbourhood planning (Box 6.1)?

The condominium sites have wide streets and some space between the blocks but they are also compact and have a high density of people. There is some mixed land use, with units allocated for commercial purposes, but the location on the edges of the city means there are limited sources of employment. The sites are predominantly for the single function of housing. The condominiums are designed for low- and middle-income families, so there is little social mixing.

Summary of Study Session 6

In Study Session 6, you have learned that:

- Urban development causes a change in land cover with decrease in permeable surfaces and increase in hard, impermeable surfaces. The loss of agricultural land adds pressure on the food production system.

- This change in land cover reduces infiltration of rainwater into the ground, increases the rate and volume of surface run-off and may lead to flooding and soil erosion. It may also lead to raised temperatures in cities.

- Urban planning aims to avoid the problems of unplanned development, to design towns and cities that meet the needs of the people who live in them, and to provide a healthy environment.

- Urban planning has complex requirements which include consideration of housing quality and affordability; infrastructure for water, sanitation and waste management; effective drainage systems; and green spaces.

- In Ethiopia, many new condominiums have recently been built according to the Integrated Housing Development Programme’s plans for new housing for low- and middle-income households.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 6

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions.

SAQ 6.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 6.1 and 6.2)

You have come across the following terms in this study session when you have been reading about land use and the physical environment. Beside each term write a definition and then list the parts of the physical environment involved: atmosphere, water, or land.

| Term | Definition | Part(s) of physical environment |

| Urban heat island | ||

| Land use | ||

| Deforestation | ||

| Impermeable surfaces | ||

| Land cover |

Answer

| Term | Definition | Part of physical environment |

| Urban heat island | Effect caused by heat energy radiated from hard surfaces in large cities that raises temperature relative to surrounding rural areas, especially at night | Land, atmosphere |

| Land use | Arrangements, activities and inputs by people to produce, change or maintain a certain land cover type | Land |

| Deforestation | Clearance of forest areas | Land, water |

| Impermeable surfaces | Hard surfaces such as roofs, roads and pavements that water cannot infiltrate | Land, water |

| Land cover | Visible cover of the land such as forest, grassland, farmland, desert | Land |

SAQ 6.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 6.1 and 6.3)

What is the aim of urban planning? List three problems of unplanned urban development that can be solved by urban planning.

Answer

The aim of urban planning is to design towns and cities to function effectively and meet the needs of people living in them.

Three problems of uncontrolled urban development that can be solved by urban planning are:

- poor housing quality, including poor construction

- lack of infrastructure and services, especially for water, sanitation and solid waste management, but also electricity, roads and transport facilities, shops, schools and health care.

- lack of drainage systems that leads to flooding.

(You might also have chosen the following problems: increase in peri-urban areas, building insecure homes in unsafe places, lack of green spaces such as parks, disease outbreaks caused by poor sanitation.)

SAQ 6.3 (tests Learning Outcome 6.1)

What is zoning and why is it no longer considered a good idea in urban planning?

Answer

Zoning is the creation of defined areas within a town that are designated for different activities, for example zones for housing, commerce and industry, with the aim of improving urban living conditions by separating people from land uses that are harmful, such as industry. Zoning is no longer considered a good idea as it had the unintended effect of creating a social divide by separating well-off people and poorer people into different areas. This social separation was associated with inequality in services and facilities available in different zones – with poorer people having worse services and facilities.

SAQ 6.4 (tests Learning Outcome 6.4)

The three pillars of sustainability are economics, society and environment. For each pillar, give an example to show how urban planning can contribute to sustainable urban living.

Answer

We have selected the following, you may have chosen other examples:

- Economics – urban planning should consider economic benefits, for example affordable housing and employment.

- Society – urban planning needs to consider social equity, for example planning for mixed land use developments that integrate different functions of residential, commercial and business together, so that there is equitable access to services and facilities.

- Environment – urban planning should protect the environment. For example, it should provide sufficient green spaces; these areas of natural ground absorb run-off and assist in the problems of surface water drainage.

SAQ 6.5 (tests Learning Outcome 6.5)

Imagine that you are an urban WASH worker and have been asked to summarise in a short written report the achievements and challenges of the Integrated Housing Development Programme (IHDP) for people who have never heard of it before. In your report you should include a description of the IHDP, a list of its achievements and a warning about the challenges faced in its implementation.

Answer

The Integrated Housing Development Programme (IHDP) is an Ethiopian government-led programme begun in 2005 to provide new, affordable housing for low- and middle-income people. It was set up under the Urban Development Package which set out the answer to the question ‘what’ was the government going to do to deliver urban-based public services of jobs, houses, roads, schools, clinics and water supply.

The achievements of the IHDP are as follows: implementation in 56 towns to date; building of many condominiums in Addis Ababa; creation of 176,000 jobs in construction and mineral extraction; increased home ownership; and improved living conditions for many people.

There have also been, however, a number of challenges in its implementation. The IHDP has been suspended outside Addis Ababa because the high-rise condominiums were unpopular in smaller, low-rise towns. Where condominiums have been built, there have been delays in infrastructure and essential services such as electricity and sewerage because companies are unable to keep up with demand and there are concerns about the construction quality of some blocks. There has also been a reduction in planned green spaces and communal buildings for social activities in order to increase housing density and reduce costs. Although the condominiums are popular, they are expensive, which has led to some people sub-letting their units, or buying units that are smaller than required, leading to overcrowding. As condominiums have mainly been built on the edges of Addis Ababa where there is little employment, this has meant increasing pressure on transport because people have to travel into the city for work.