Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 7:12 AM

Study Session 13 Human Values and Behaviour

Introduction

In Study Session 8 you learned about ways in which pollution of the air, water and food can affect the environment and human health. In this study session we focus on the human values and behaviour that either protect our health and the environment from contamination by human and animal waste, or result in exposure to sources of pollution. We describe how behaviour is influenced by knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and traditions concerning the causes of disease and responsibility towards the environment, and also by household economic factors and gender issues. These aspects of the social environment must be considered in your own community if you are to be successful in preventing and controlling infectious diseases and environmental pollution by encouraging everyone to use good WASH practices consistently and to value them as normal practices.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 13

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

13.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 13.1, 13.2 and 13.3)

13.2 Describe ways in which the social environment of knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and traditions can affect human values and behaviour towards WASH practices. (SAQs 13.1 and 13.3)

13.3 Give examples of how positive or negative human values and behaviour concerning WASH practices can affect infectious disease transmission and the physical environment. (SAQs 13.1, 13.2 and 13.3)

13.4 Explain why it is important to address economic factors and gender issues when devising a communication strategy to promote good WASH practices. (SAQs 13.1 and 13.3)

13.1 The physical and the social environment

Everywhere you look, you see people, animals and plants living in fields and forests, streams and hillsides, or in villages, towns and cities. These are all part of the physical environment of the ‘real world’ that we can see with our eyes and touch with our hands. In your town, there are physical structures that humans have built or made, including houses, churches, mosques, schools, shops and market stalls, a health centre, kebele office or a police station.

Can you identify some other features of the physical environment in your town? (Figure 13.1 gives some clues.)

You may have mentioned roads and traffic, pavements, advertising signs, electricity cables and lamp-posts, or perhaps ditches to catch water and prevent flooding in the rainy season, which are not visible in Figure 13.1.

The physical structures we have mentioned also provide the local population with various kinds of social services. For example, a church or mosque provides religious services; a school provides education; shops and markets provide access to food and other products; roads provide transport links; and houses provide shelter. These services contribute to the social environment of the community. The social environment also includes the attitudes, beliefs, practices and traditions that are expressed by the members of a community. Unlike the physical structures, they cannot be seen.

Case Study 13.1 will help you to see the difference between the physical and the social environment. Read the case study and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 13.1 Ato Belay interviews community members on their latrine use

Ato Belay was recently employed on an urban Health Extension project. He was given a task to prepare the annual plan of action on excreta management in his urban neighbourhood. He went house to house to collect data to identify who has, or has not, got a latrine, in order to design his plan of action. He recorded that less than 40% of households had latrines. The others were using open defecation and open urination in public places such as close to fences, around riverbanks, near waste containers or in the bush.

Ato Belay asked questions to find out why households do not have latrines, or do not use their latrine. Some said that constructing a latrine is too expensive. Others reported that collecting faeces in a latrine creates bad odour; they believed defecating in the open air is healthier because bad odour causes illness; others also said that open spaces have ‘good air’ when defecating. When Ato Belay asked about soiling the physical environment, some community members said: ‘Our ancestors never used latrines and the bush is not harmed by defecating there.’ Some people said that children should defecate in the open because latrines are only meant for adults. Others believed that children may be exposed to ‘evil’ influences emerging from the latrine pit if they use it at night. Ato Belay concluded that open defecation was the main sanitation problem in his community.

Now answer these questions:

- Which parts of the physical environment did Ato Belay ask about?

- What was the social environment he investigated?

- What was the public health problem he identified?

- What information does Ato Belay need to find out from community members in order to design his sanitation action plan?

The answers are as follows:

- The physical environments he asked about were latrines and the places where people urinated or defecated in the open.

- The social environment he investigated was the attitudes and beliefs of community members about using latrines and open defecation.

- The public health problem he identified was the widespread practice of open defecation by adults and children.

- Ato Belay needs to find out why residents are not using latrines even when the household has the facility, and why households without a latrine do not want to build one.

The part that the social environment plays in the above example demonstrates the importance of understanding why someone is defecating in the open or not using their latrine. So now we will look more closely at how the social environment influences WASH practices.

13.2 How does the social environment influence WASH practices?

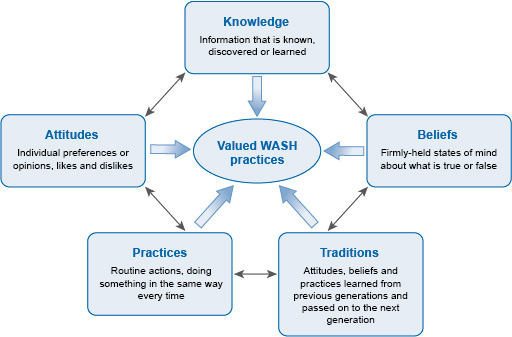

The building blocks of our behaviour lie in our knowledge, practices, attitudes, beliefs and traditions, all of which contribute to the social environment. Figure 13.2 summarises the interactions between these invisible aspects of the inner personal world of every individual and their community, and shows that they all influence whether good water, sanitation and hygiene practices are adopted.

We have called the behaviours at the centre of Figure 13.2 ‘valued WASH practices’ to indicate that they are actions that a community values and approves. Individuals who are observed doing these actions (for example, washing their hands before eating) gain credit from others in the community because they are behaving in these valued ways. An example of a behaviour that is valued in rural Ethiopia is debo, the practice of neighbours working together to harvest the crops from each farm in turn.

Notice that each part of Figure 13.2 is interacting with all the other parts to influence valued WASH behaviours. The main message of the diagram is that you must consider all these aspects in the social environment of your community if you want to be successful in replacing unhealthy or environmentally damaging behaviours by valued WASH practices. We begin by considering the limitations of knowledge to bring about behaviour change from unhealthy to good WASH practices.

13.2.1 Knowledge of WASH practices is not enough to change behaviour

Knowledge can be defined as all the information we have learned and synthesised during our growth and development.

We assume you know that people who drink dirty water may get sick as a result because harmful bacteria live in the water. Think for a moment about how you acquired this knowledge?

You may have been told not to drink dirty water by your parents; or perhaps you learned about bacteria at school; or maybe the Health Extension Worker made a poster about only drinking clean water to avoid getting diarrhoea; you could have heard about it on the radio, or learned from your own experience if you drank dirty water as a child and developed diarrhoea afterwards.

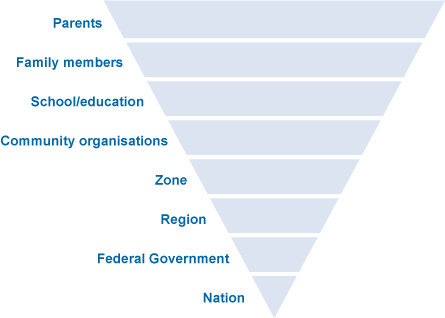

Figure 13.3 summarises the ‘upside-down pyramid’ of sources of knowledge acquired during a lifetime.

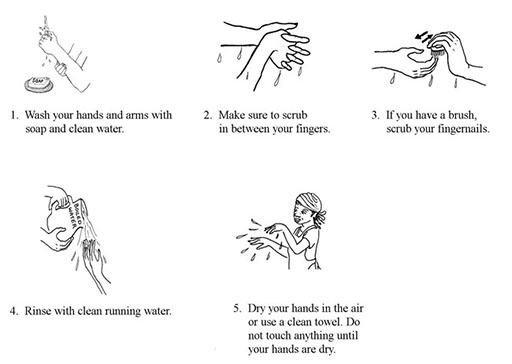

Education is a key factor in improving the knowledge of WASH issues in a community. Learning about hygiene and sanitation in school is a particularly important driver of behaviour change. The Ethiopian government has a strong commitment that all children should attend school. If children learn the right way from a young age, they will keep good WASH practices throughout their lives. For example, they can be taught the correct way to wash their hands at critical times, that is, before and after preparing food or eating, and after urinating, defecating or cleaning a child’s bottom (Figure 13.4).

However, health education programmes are often unable to achieve behaviour change simply by giving adults knowledge of the health risks of poor hygiene or why they should not pollute the physical environment with waste. Even if people are given accurate information about what causes diarrhoea, this knowledge is generally not enough to persuade them to change poor hygiene and sanitation practices, their routine actions, doing something in the same way every time. For example, people whose routine practice is to defecate in the open every day are unlikely to change their behaviour simply because they have been given new knowledge about the risks to their health and the environment.

13.2.2 Attitudes, beliefs and traditions influence WASH practices

There are several reasons why unhealthy WASH practices persist, even if people have been given good information to help them change for the better. If you look again at Figure 13.2, you can see we have put ‘attitudes’ and ‘beliefs’ on either side of ‘valued WASH practices’. Attitudes are individual preferences or opinions about what a person likes or dislikes. Beliefs are firmly held states of mind about what is true or false. One reason for the persistence of bad WASH practices, even when correct knowledge is available, is that people have attitudes and beliefs that make them ignore the facts.

Can you suggest an attitude and a belief that people might express about not using a latrine even when there is one nearby?

Here are our suggestions, but you may have given other good answers:

- Attitudes against using latrines: ‘I dislike using latrines because they smell bad’; or ‘I prefer to empty my bowels in the open because the bad smell is blown away by the fresh air’.

- Beliefs against using latrines: ‘The bad odour collects in the latrine and causes disease if you breathe it into your body’; or ‘It is safer to defecate in the open because there are evil influences in latrines’.

Good WASH practices at community level also include handwashing, accessing clean drinking water, and keeping the physical environment clean and free from waste. Sustaining these practices builds our health, improves our lifestyle and helps us all to live longer. But first, negative attitudes and beliefs must be overcome and replaced with valued behaviours. For example, handwashing with soap before eating is not practised by everyone in Ethiopia, even though it prevents transmission of infection from dirty hands to the mouth. (Figure 13.5).

The example we gave earlier of debo – the valued practice in rural communities of neighbours helping to harvest crops from each other’s fields – can also be termed a tradition, a behaviour that is learned from previous generations and passed on to the next generation. Some traditions, like debo, bring positive benefits to the community and also to the environment. But some traditions expose people and the environment to possible harm.

Open defecation is a tradition in communities like the one we described in Case Study 13.1. Can you recall the tradition mentioned by some of the people he spoke to?

They told him that they continued to defecate in the open because their ‘ancestors never used latrines’. Behaviour that was accepted by the ancestors has become a tradition that people in this community pass on to their children.

Tradition is one reason why, according to the report of the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation in Ethiopia (JMP, 2014), about 37% of Ethiopians were still practising open defecation in 2012.

Traditions are very difficult to change because everyone in a community believes it is the right way to behave. Individuals who challenge the tradition are likely to meet opposition from the majority who want to go on doing things in the old way. If open defecation or not washing the hands at critical times is considered normal and traditional in a community, it will take time and effort to persuade people that using a latrine (Figure 13.6) or handwashing with soap are valued practices that benefit the whole community and also protect the environment.

13.3 Other influences on WASH practices

In this section, we discuss three factors that influence whether WASH practices are adopted in a community: economic factors; gender and privacy issues; and caring for the environment.

13.3.1 Economic factors influence WASH practices

The cost of constructing a protected water source, a latrine or handwashing facilities may be too much for some households to pay, especially when purchasing WASH facilities and services is seen as a lower priority than spending limited financial resources on other needs. Primary priorities for most households, whether urban or rural, include secure housing, food, clothing and education for their children, and possibly also transport costs to take children to school or adults to work. Installing even the most basic latrine or handwashing basin may be unaffordable, but people can still wash their hands with a bowl and a bar of soap (Figure 13.7).

However, constructing a latrine is much more expensive than buying a plastic bucket and some soap. The typical cost of a circular concrete slab for a pit latrine was about 260 ETB in 2015, plus there is also the cost of digging the pit and constructing a shelter, and paying a carpenter or bricklayer.

Local government may be able to assist households to obtain loans at low interest rates so that they can install WASH facilities. Community WASH projects may also be funded by local contributions and provide shared labour to build a communal latrine or protect a water source from contamination by human and animal waste.

Although there are costs involved, installing a WASH facility can also save some expenses for a household that uses them consistently. Diarrhoea, worm infestations and other communicable diseases resulting from poor WASH practices cause a significant economic burden on individuals, families, communities and Ethiopia nationally.

Can you think of expenses that the family of a child with severe diarrhoea will have to pay?

You may have mentioned the cost of treatment, including transport costs if the child goes to the health centre; and family members may lose income from their employment while caring for the sick child.

These expenses could have been reduced by using a latrine, handwashing at critical times and accessing improved water sources. The prevalence of diarrhoea among children in Ethiopia is still high: it tops the list of causes of morbidity (illness) in children under 5 and accounts for 16.5% of cases (MoH, 2014). If you multiply the costs to a single family with a sick child by the huge number of illness episodes that could be prevented by good WASH practices, you can see that WASH could bring huge economic benefits to the nation.

13.3.2 Gender, privacy and access issues influence WASH practices

It is against Ethiopian culture for women and girls to urinate in public, but it is quite common to see men and boys urinating in the street. Access to a safe and private place for this purpose is therefore a high priority for women, who may suffer great discomfort to avoid urinating or defecating until night time when they can go without being seen. However, this also exposes them to the risk of rape or robbery. Therefore, the provision of household latrines is a gender issue: it affects males and females differently.

Another difference between the genders in most Ethiopian families is that a woman prepares all the food. If her hands are clean when she touches food items and she washes fruits, vegetables and cooking utensils in clean water, the risk of transmitting infectious organisms to family members is much reduced. Research has shown that washing the hands with soap at critical times can reduce the incidence of diarrhoeal diseases in families by as much as 44%, and even without soap the reduction is about 30% (Curtis et al., 2011). This is very important in Ethiopia, where traditional food is eaten with the hands (Figure 13.8).

Installing handwashing facilities or building a latrine for the household therefore brings benefits to women in particular, but also improves the health of all family members.

13.3.3 Caring for the physical environment improves health outcomes

In Study Session 8, you learned about pollution of the urban environment when human excreta, household waste, animal droppings and other filth collects in the streets. All waste products are sources of disease because they attract rats, mice, dogs, flies and mosquitoes that can transmit infectious organisms to people. Bacteria, viruses and worms in rotting food and faeces are washed by rain into the soil and local sources of drinking water; they contaminate crops and get onto the hands of people working on the land or children playing. Unless hands are washed at critical times, the transmission of infection from soil to hands and into mouths is impossible to prevent. Therefore, keeping the community environment clean and free from waste (Figure 13.9), and persuading people of the health benefits of handwashing and latrine use are key goals for health workers and WASH workers.

In addition to protecting the environment as a way of protecting human health, we should also see the beautiful land, lakes and rivers, animals and plants of Ethiopia as our heritage.

13.4 Making WASH practices socially accepted and valued

It should be the aim of every WASH worker to make WASH practices socially acceptable and the norm in your community. If the majority of community members value and promote WASH practices, social pressure to conform will be felt by any individuals or households who do not behave in accordance with these shared norms. In model WASH communities, every household will use a latrine, hands are always washed at critical times, homes are kept clean and the neighbourhood is free from dirt and waste.

You will have to use excellent communication methods to give people accurate knowledge of the benefits of good WASH practices and the risks to health and the environment of persisting in harmful behaviours. Consultation and joint learning can be achieved through behaviour change communication (BCC) methods. These are a range of methods for communicating messages to communities and individuals about desirable changes to their behaviour, for example to improve hygiene practices. BCC methods include community meetings, local health conferences and community conversations (Figure 13.10), which enable everyone to share their views on WASH-related issues. BCC may include education of household members by urban Health Extension Workers and involvement of the Health Development Army.

To achieve the national goals for improvement in WASH provision, the ultimate aim is that community members, working with the local administration, have a clear plan of action for changing behaviour locally, so that good hygiene and sanitation practices become the norm for every household. Caring for the physical environment around us, whether it is the urban world of houses and streets or the natural world of fields and streams, is a responsibility that everyone should value. Evaluation of WASH practices as they are implemented enables you and the community to keep track of the improvements to health and the environment that have been achieved.

Summary of Study Session 13

In Study Session 13, you have learned that:

- The physical environment is the world we can see around us; the social environment is the invisible world of social interactions between people, their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, practices and traditions.

- As a WASH worker you should understand the attitudes and beliefs about WASH practices in your community and whether they are valued or rejected.

- You should share your knowledge of how WASH practices benefit human health and protect the environment, but knowledge alone may not convince people to change traditional behaviours.

- Misconceptions, unhelpful attitudes and factually incorrect beliefs must be respectfully challenged and changed if you are going to achieve the goals for WASH improvement.

- Economic factors make it difficult for families to afford WASH facilities or make them a priority; however, repeated episodes of avoidable infections are a financial burden that WASH practices could reduce.

- Gender differences in sanitation behaviour mean that women in particular will be more comfortable, private and safe if they can access a latrine.

- Handwashing at critical times protects everyone from infection.

- Protecting the environment from pollution by faeces and other waste is a responsibility that everyone should share and value.

- Behaviour change communication strategies engage the whole community in developing an action plan, to make WASH facilities more available and good WASH practices the norm.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 13

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions.

SAQ 13.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.1 to 13.4)

First read Case Study 13.2 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 13.2 Ato Belay observes handwashing practices at a wedding

Ato Belay was invited to a wedding where food and drinks were served. He observed that most people washed their hands in plain water before eating, but used soap after eating. Some people did not wash their hands at all, so he politely asked them why not. Some said: ‘The handwashing facility is too crowded’, or ‘There is not enough soap’. Others believed there was no health benefit from handwashing. Some said that soap and water was for washing clothes and should not be wasted on washing hands.

- a.What handwashing practice was used by most people at this wedding?

- b.Identify a negative belief concerning handwashing at this wedding.

- c.Identify a negative attitude concerning handwashing at this wedding.

- d.How may economic factors have influenced handwashing behaviour at this wedding?

Answer

- a.The handwashing practice used by most people at this wedding was washing their hands in plain water before eating, but using soap after eating.

- b.A negative belief expressed by some wedding guests is that there is no health benefit from handwashing before eating.

- c.A negative attitude concerning handwashing at this wedding is that it is a waste of soap and water which should be saved for washing clothes.

- d.Better handwashing facilities and more soap would cost more to provide and may not have been affordable at this wedding.

SAQ 13.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.1 and 13.3)

- a.What are the critical times for handwashing that can have the greatest impact on infectious disease transmission?

- b.What percentage reduction in diarrhoeal disease episodes is achieved by routine handwashing at critical times with plain water or using water and soap?

Answer

- a.The critical times for handwashing are before and after preparing food or eating, and after urinating, defecating or cleaning a child’s bottom.

- b.Handwashing with plain water at critical times can reduce episodes of diarrhoea by about 30%; using soap and water reduces diarrhoeal diseases by about 44%.

SAQ 13.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.1 to 13.4)

How could building a latrine and ensuring all family members use good WASH practices benefit:

- a.the economic sustainability of the household?

- b.the women and girls in the family?

- c.the physical environment around the household?

Answer

Building a latrine and ensuring all family members use good WASH practices would have the following benefits:

- a.The economic sustainability of the household will be improved because there will be fewer episodes of diarrhoea and other infections, so the cost of health care, including transport to a health facility will be saved and adults will not lose so much in earnings when they are looking after a sick child.

- b.The women and girls in a family with a latrine will benefit from the privacy and security of having a safe place to urinate and defecate during the day, instead of the discomfort and risks associated with waiting to ease themselves in the open after dark.

- c.The physical environment around the household will not be contaminated by human waste, which attracts vermin and flies that spread infection; also, the waste will not be washed into the soil and local water sources where pollution not only affects the health of people but it also damages other animals and plants.