Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 8:40 AM

Study Session 15 National Policy Context in Ethiopia

Introduction

Safeguarding the environment requires coordinated effort by individuals, communities, institutions and governments. In this final study session you will learn about the Ethiopian government’s policy response to the challenges of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) with a focus on the relevant health, water and environmental policies. We start this study session with an overview of the different types of national law and policy before briefly describing the most important policies and programmes that relate to WASH.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 15

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

15.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 15.1)

15.2 Describe the hierarchy of laws in Ethiopia. (SAQ 15.1)

15.3 Briefly describe the process of policy development in Ethiopia. (SAQ 15.2)

15.4 Outline the main policies in health, water, and the environment that are related to WASH. (SAQs 15.3 and 15.4)

15.1 Laws and policies in Ethiopia

There are many different words used to describe the various types of law and policy, so we start with an overview of the terminology.

15.1.1 The hierarchy of laws

The highest law in Ethiopia is the Constitution (Proclamation No.1/1995) which was adopted by the highest legislative body (parliament) and signed by the head of state in 1995. It states (FDRE, 1995):

The Constitution is the supreme law of the land. Any law, customary practice or a decision of an organ of state or a public official that contravenes this Constitution shall be of no effect.

The Constitution declares that Ethiopia is a federal and democratic state, and that religion and the state are separate. It describes the parliamentary structure of government and the human rights that are protected in the country. The Constitution states that the power to make national laws lies with the House of People’s Representatives (HPR) although some of their law-making powers are delegated to the Council of Ministers, which is the highest executive body in the government structure (Degol and Kedir, 2013).

The Constitution is at the top of a hierarchy of laws with different levels of importance, as shown in Figure 15.1.

Proclamations come below the Constitution in the hierarchy. They are acts of parliament, discussed and voted on in the HPR and signed by the president of Ethiopia. International treaties that have been ratified by Ethiopia (such as those you read about in Study Session 14) have similar status to proclamations because they are also enacted by the HPR.

Regulations are the next level. They are issued by the Council of Ministers to supplement a proclamation. Regulations have detailed descriptions of the provisions of the respective proclamation.

Directives are the lowest level in the Ethiopian legislation hierarchy. They describe how regulations should be implemented and are usually developed by a ministry or a department within a ministry.

At regional level, there is a similar hierarchy of state laws that includes proclamations, regulations and directives.

15.1.2 Policies, strategies and programmes

Policies are important statements of government plans. They lie outside the hierarchy of laws because they do not have the same legal status as proclamations, regulations and directives; however, they are related. Policies are statements of overall purpose that set out goals and provide principles that should be followed to achieve those goals. Policy goals and principles are made into laws by proclamations and regulations.

A strategy provides details for implementing a given policy. It sets out how policy goals will be achieved, for example by identifying who should be involved, and allocating roles and responsibilities. Examples of national strategies include the Food and Nutrition Strategy, Poverty Reduction Strategy, Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy, and National Hygiene and Sanitation Strategy.

Policies and strategies are put into effect in a range of programmes and projects, which could be described as action plans for implementation. Programme is a broad term used to describe any set of related events, activities or projects. Government programmes are specific to a particular sector and often cover a specified period such as five years. (Note that the word ‘policy’ is sometimes used in a more general sense to include any statement of overall aims, including strategies and programmes as well as named policies. We have used it in this broader sense in this study session.)

Ethiopian Government policies are based on the provisions of the Constitution. Several policies seek to deliver public benefits, including the Health Policy, Population Policy, Women’s Policy and the Ethiopian Water Resources Management Policy.

Public policy is created at all levels of government – federal, regional, zonal and woreda – but it is not only governments that have policies. Organisations, and even families and individuals, develop policies to guide their actions.

Can you think of any policies you are subject to at your place of work? (Or someone that you know if you are not currently in employment.)

The organisation you work for is likely to have a number of policies that apply to you, such as policies on holidays, sickness leave entitlement and disciplinary matters, to name a few.

15.2 Policy development

Policies are designed to serve the public at large, so policy development should be participatory, democratic and transparent. The process involves both top-down (initiating draft policies) and bottom-up (getting responses and feedback) approaches. Policy development has three main processes:

- identifying the need for a policy

- formulating the policy

- monitoring the policy and evaluating its effectiveness.

15.2.1 Initiating a policy idea

Policy can be reactive or proactive. Reactive policy is formulated in response to issues or concerns and to solve existing problems; proactive policy is designed to prevent a problem arising. Proactive policies are more difficult to formulate because it is challenging to persuade decision makers to allocate funds and other resources to a problem that is not yet perceived as a problem.

When you think about environmental policy, do you think it is mostly reactive or proactive? Which type of policy do you think is best suited to environmental issues, and why?

It is likely that you thought that environmental policy is largely reactive, for example, a policy on pollution is a response to a problem caused by pollution. But proactive policy would be better for environmental issues because it prevents problems from happening in the first place.

Ideas for new policies may come from the House of People’s Representatives (the parliament), from a specific ministry, or from the Council of Ministers through its Expert Group. The Expert Group may identify policy gaps based on research or public opinion, which are then developed and considered by the Council of Ministers.

15.2.2 Formulating the policy

Formulating a policy and developing a draft document is done by the process owner (policy-making institution). They will organise their own Expert Group or committee of government stakeholders to be responsible for the task. Sometimes a consultancy firm is used to fully develop the draft.

The draft policy document is disseminated to different audiences including policy beneficiaries and other stakeholders who may include federal and regional ministries, community and professional representatives, academic institutions, the donor community, etc. The feedback from these interested parties enables the Expert Group to enrich and revise the draft policy, which can then be submitted for approval. Once it has been approved internally it can be submitted to the Council of Ministers. Further discussion follows and modifications and additions are considered.

The Council of Ministers submits the revised policy to the relevant parliamentary committee who discuss it and may ask for clarifications from the process owner. The committee may call on public opinion in specially arranged meetings to get additional inputs to shape the final draft.

The revised draft policy will then be debated in parliament. Final amendments can be made and then the policy document is published. Proclamations and regulations linked to the policy are published in Negarit Gazeta and become law. The Negarit Gazeta is the official government gazette for the publication of all federal laws.

15.2.3 Implementing and monitoring

After the policy or proclamation is put into practice, its implementation should be monitored so that its effectiveness and continuing relevance can be evaluated. Monitoring may involve routine discussion of progress at meetings of the relevant ministry, annual meetings with wider stakeholder groups, reports on performance delivered to parliament, or field evaluations. This may lead to identification of policy gaps and then possible requests to the Council of Ministers and parliament to repeal or modify the provisions. In this way, policy implementation can be improved and kept up to date.

15.3 The Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

The Constitution includes several articles that are relevant to WASH, public health and the environment (FDRE, 1995).

Article 41/4: The State has the obligation to allocate ever-increasing resources to provide to the public health, education and other social services (economic, social and cultural duty and objectives).

Article 42/1: Workers have the right to reasonable limitation of working hours, to rest, to leisure, to periodic leaves with pay, to remuneration for public holidays as well as a healthy and safe work environment (labour rights).

Article 44/1 states that all persons have the right to a clean and healthy environment (environmental rights).

Article 89/8 states that government shall endeavor to protect and promote the health, welfare and living standards of the working population of the country (economic duty and objective).

Article 90/1 To the extent the country’s resources permit, policies shall aim to provide all Ethiopians access to public health and education, clean water, housing, food and social security (social duty and objective).

Article 92/1: Government shall endeavor to ensure that all Ethiopians live in a clean and healthy environment (environmental duty and objective).

These articles give rights to citizens and assign duties and objectives to the government. The Constitution states that all persons have the right to a clean and healthy environment, and the government has a duty to ensure that all Ethiopians live in a clean and healthy environment as far as it is able, which includes access to and use of clean water, sanitation and hygiene facilities.

Safeguarding the environment from any human-made damage is covered by Articles 92/2 and 92/4 which state that projects, investments or developments should not destroy and pollute the environment (water, air and soil).

15.4 Health policies

The rights and principles set out in the articles of the Constitution form the basis of government policy. In the health sector there are a number of different policy, strategy and programme documents that are relevant to WASH.

15.4.1 Health Policy (1993)

The Health Policy of 1993 outlines the need for strategies linked to the democratisation and decentralisation of the health system, and inter-sectoral collaboration. It specifies the need for ‘accelerating the provision of safe and adequate water for urban and rural populations’, ‘developing safe disposal of human, household, agricultural and industrial wastes and encouragement of recycling’, and ‘developing measures to improve the quality of housing and work premises for health’ (Transitional Government of Ethiopia, 1993). The Health Policy has led to several health-related programmes and strategies.

15.4.2 Health Sector Development Programme

The Health Sector Development Programme (HSDP) guides the development of national long-term plans in the health sector including those concerning water, sanitation and hygiene. The current programme, HSDP IV, covers the years 2010 to 2015 and is the fourth in a series of five-year programmes. It set targets at the national level for latrine access, household use of water treatment and safe water storage practices, and achievement of open-defecation-free (ODF) status in villages (MoH, 2010).

The Health Extension Programme (HEP) is an innovative community-based primary care system developed under the HSDP. Health Extension Workers deliver community-based antenatal and postnatal care as well as basic health information about WASH (Figure 15.2).

Health Extension Workers (HEWs) are often drawn from the communities they serve. What do you think are the advantages of this?

The HEW will understand the community and its cultural practices and will be better equipped to adapt the health messages to the community’s situation. The HEW is also likely to be trusted by the community as one of their own.

15.4.3 National Hygiene and Sanitation Strategy

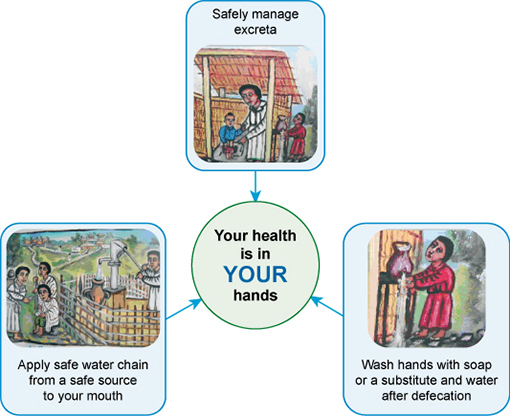

The National Hygiene and Sanitation Strategy (NHSS) of 2005 was developed by the Ministry of Health to complement the Health Policy. Figure 15.3 shows the image on the front cover of the document. This clearly illustrates the links between health and the three components of WASH.

The strategy starts with a ‘Sanitation Vision for Ethiopia’, which is: ‘100% adoption of improved (household and institutional) sanitation and hygiene by each community which will contribute to better health, a safer, cleaner environment, and the socio-economic development of the country’ (MoH, 2005). The strategy first describes the current situation, as it was in 2005, and then sets out objectives and plans for achieving the goal of the Vision Statement, which are being carried forward in various programmes and projects.

15.5 Water policies

In the water sector, there are also several relevant government policy documents. Two of the most important are briefly described here.

15.5.1 Ethiopian Water Resources Management Policy

This policy aims to enhance and promote the efficient and fair use of water resources for socio-economic development in a sustainable manner (MoWR, 1999). It has specific provisions related to water supply and sanitation, irrigation, and hydropower, and also specifies policy on cross-cutting issues such as allocation of resources, watershed management, technology and gender.

15.5.2 Ethiopian Water Resources Management Proclamation (No. 197/2000)

This proclamation was issued in 2000 with the purpose of protecting natural water sources from degradation, excessive use and pollution. It gave authority to the Ministry of Water Resources to issue licences for the development of water resources (dams, drinking water supply and irrigation schemes) and permits to discharge wastes.

15.6 Climate policies

As you know from previous study sessions, climate change is causing higher temperatures and changing rainfall patterns leading to increased drought and flooding. Flooding can destroy poorly constructed latrines and pumps and contaminate drinking water sources unless they are built with the risks from flooding in mind.

Look at the pump in Figure 15.4. What aspects of its construction will help resist damage from flooding?

The base is raised higher than the ground surface and it has a solid concrete cover which should be watertight to prevent floodwater entering the well or borehole.

15.6.1 Ethiopian Programme of Adaptation to Climate Change (EPACC)

On the basis of its vulnerability to climate change, Ethiopia adopted the National Adaptation Programme of Action in 2007. This was updated with the Ethiopian Programme of Adaptation to Climate Change in 2011, which looks at the challenges of climate change and seeks to design adaptation responses (The Red Desk, 2015).

EPACC envisages that each sector, region and local community in Ethiopia will have its own programme of adaptation. Adaptation practices are indicated for each sector including crop production, livestock, water, health, education, energy, infrastructure, institutional capacity and cultural heritage.

15.6.2 Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy

While the EPACC focuses on climate change adaptation, the government’s Climate Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) strategy, also launched in 2011, focuses on climate change mitigation. It seeks to cut the country’s carbon emissions, as you read in Study Session 12.

What is the overall aim of the CRGE strategy?

It aims to limit greenhouse gas emissions to 2011 levels while supporting economic development and growth.

15.7 Environment policies

There are several national policy documents that relate to environmental protection.

15.7.1 Environmental Policy of Ethiopia (EPE)

This policy, issued in 1997, aims to maintain the health and quality of life of all Ethiopians and to promote sustainable social and economic development. It seeks to do this through the sound management and use of resources and the environment as a whole, in accordance with the principles of sustainable development. It considers the rights and obligations of citizens, organisations, and government to safeguard the environment as indicated in the Constitution of Ethiopia. The EPE is a comprehensive document that defines policies for ten separate environmental sectors, covering soil and agriculture, forest and woodland, biodiversity, water, energy, minerals, human settlement, industrial waste, climate change and cultural heritage (FDRE, 1997). It also includes policies for ten cross-sectoral issues that need to be considered for effective implementation: population, community participation, land tenure, land use, social and gender issues, environmental economics, information systems, research, impact assessment, and education.

15.7.2 Environmental Impact Assessment Proclamation (No. 299/2002)

This proclamation follows the principles of the international agreement on Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) that you read about in Study Session 14. Major development projects that are likely to damage the environment (physical and social) are expected to have an EIA that identifies hazards and possible damage so that they can be mitigated during the project development. The proclamation outlines the duties of the proponent (developer) and specifies the details that must be included in the assessment and the impact study report (FDRE, 2002a). Approximately 30 EIAs are produced at the federal level each year, which is relatively low compared to other countries, but most EIAs happen at the regional level (SIDA, 2013).

15.7.3 Environmental Pollution Control Proclamation (No. 300/2002)

Pollution is defined in this proclamation as: ‘any condition which is hazardous or potentially hazardous to human health, safety, or welfare or to living things created by altering any physical, radioactive, thermal, chemical, biological or other property of any part of the environment in contravention of any condition, limitation or restriction made under this Proclamation or under any other relevant law’ (FDRE, 2002b).

The proclamation states that ‘no person shall pollute … the environment’ but also includes provisions for prevention and penalties if pollution does occur. It follows the ‘polluter pays principle’ and requires the person who causes pollution to pay for any clean up. Specific articles detail the need for proper management of hazardous and municipal waste and the adoption of environmental standards with reference to wastewater effluents, air, soil, noise and waste.

15.7.4 Solid Waste Management Proclamation (No. 513/2007)

This proclamation aims to prevent environmental damage from solid waste while harnessing its potential economic benefits. It defines solid waste management as the collection, transportation, storage, recycling or disposal of solid waste. The proclamation indicates the need for involvement of the private sector for effective management and describes the safe transport of solid waste including hazardous waste (FDRE, 2007).

15.7.5 Prevention of Industrial Pollution Regulation (No. 159/2008)

The purpose of this regulation is clear from its name. Factories must make sure their liquid waste meets environmental standards, and obtain a permit before discharging any liquid waste (FDRE, 2008). The factory must monitor the composition of its waste, keep records and report periodically to the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA).

15.7.6 Environmental and Social Management Framework

This framework document was prepared in collaboration with the World Bank. It sets out procedures to ensure that investments in WASH are implemented in an environmentally and socially sustainable manner (FDRE, 2013). It recognises the importance of protecting people and the environment from the negative impacts of development and safeguarding the lives and livelihoods of the population.

15.8 One WASH National Programme

To conclude this overview of national policies, and to conclude this module, we must consider the One WASH National Programme (OWNP). The OWNP, as the name suggests, is a single programme that combines water with sanitation and hygiene (Figure 15.5). Announced in 2013, it aims to address the WASH challenges in Ethiopia by adopting a unified and collaborative approach. The overall objective of the OWNP (FDRE, 2014) is:

to improve the health and well-being of communities in rural and urban areas in an equitable and sustainable manner by increasing access to water supply and sanitation and adoption of good hygiene practices.

The innovative characteristic of the OWNP is that it involves four ministries: Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy; Ministry of Health; Ministry of Education; and Ministry of Finance and Development. The four ministries have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that sets out their roles and responsibilities. It therefore cuts across the traditional separation of responsibilities between ministries and has structures and processes designed to ensure closer cooperation and collaboration between all the stakeholders.

The guiding principles of the OWNP are integration, alignment, harmonisation and partnership and its motto, ‘One Plan, One Budget, One Report’, neatly summarises its approach. Funds from external donors are pooled in a Consolidated WASH Account which will help to reduce problems of fragmentation of resources and lack of coordination between development programmes. The organisational structure of the programme describes the roles and responsibilities at all levels from the WASH National Steering Committee at federal level through Regional Steering Committees, Woreda WASH Teams and Town/City WASH Technical Teams, to Kebele WASH Teams and communities. Successful implementation of the One WASH National Programme should result in huge and sustainable changes to WASH provision in Ethiopia.

Summary of Study Session 15

In Study Session 15, you have learned that:

- There is a hierarchy of laws in Ethiopia. The Constitution is the supreme law of the land with proclamations, regulations and directives at lower levels of the hierarchy.

- Policies set out government and regional plans and provide goals and principles to be followed. Strategies and programmes provide details for how policies should be implemented.

- Development of national policies has several steps from initial idea through consultation to final approval by parliament and publication.

- The Constitution has several articles that safeguard the environment and public health.

- The Health Policy of 1993 established the overall direction for health services in Ethiopia. This has been developed in several strategies and programmes, including HSDP IV and the National Health and Hygiene Strategy.

- The Water Resources Management Policy and Proclamation set out the principles and practice for fair and efficient use of water.

- Ethiopia’s Programme of Adaptation to Climate Change and the Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy seek to adapt to and mitigate the adverse effects of climate change respectively.

- Several proclamations provide the legal framework to support the goals and principles set out in the Environmental Policy of Ethiopia.

- Unlike previous programmes for WASH improvement, the One WASH National Programme takes a unified and collaborative approach to addressing the challenges of water and sanitation in Ethiopia.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 15

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions.

SAQ 15.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 15.1 and 15.2)

Which of the following statements are false? In each case explain why it is incorrect.

- A.Proclamation is the highest law in Ethiopia.

- B.Policy sets overall goals.

- C.Policies provide details for implementation of programmes.

- D.Regulations provide detailed descriptions of the provisions of strategies.

- E.Directive is lowest in the hierarchy of law.

Answer

A is false. The Constitution is the highest law in Ethiopia.

C is false. The statement would be true if it were reversed: programmes provide details for implementation of policies.

D is false. Regulations provide further details of proclamations, not strategies.

SAQ 15.2 (tests Learning Outcome 15.3)

Why is public consultation important when developing environmental and WASH-related policies?

Answer

Article 92/3 of the Constitution states that people have the right to be consulted about environmental policies that affect them. It is important to involve all stakeholders in the development of policy so they have the opportunity to give their opinions to the policymakers and influence the outcomes. Policies should serve the public at large, so the policymakers need to be aware of all possible impacts of the policy they are formulating.

SAQ 15.3 (tests Learning Outcome 15.3)

- a.What does the Constitution of Ethiopia say about people’s environmental rights?

- b.List three WASH-related national policies.

Answer

- a.In Article 44/1, the Constitution states that ‘All persons have the right to a clean and healthy environment’. You may also have mentioned the right to a healthy and safe work environment (Article 42/2).

- b.The three main policies are the Health Policy, the Water Resources Management Policy and the Environmental Policy.

SAQ 15.4 (tests Learning Outcome 15.4)

What environmental proclamation or regulation would you use to demonstrate wrongdoing in the following examples?

- a.A factory owner is discharging toxic effluent into a nearby river.

- b.A builder has dumped old building materials such as bricks and plaster at the edge of a slum area.

- c.A transport company is transporting radioactive waste in open-topped lorries.

Answer

To some extent there is overlap between the various proclamations and regulations and in some cases more than one could be applied but possible answers are:

- a.Factory owner – Environmental Pollution Control Proclamation and Prevention of Industrial Pollution Regulation.

- b.Builder – Solid Waste Management Proclamation.

- c.Transport company – Environmental Pollution Control Proclamation.