Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 10:17 AM

Study Session 15 Public–Private Partnership and Other Commercial Opportunities

Introduction

In cities across the world it has usually been the case that a municipal (public) authority takes responsibility for urban water supply. There are now variations in this service provision. In many countries, private businesses (or operators) have joined in partnership with public authorities to provide water in arrangements called public–private partnerships. This study session explores the concept of public–private partnerships and their application in urban water supply.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 15

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

15.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 15.1)

15.2 Describe the potential of public–private partnerships in improving access to safe water. (SAQs 15.2 and 15.3)

15.3 Give examples of microenterprises that can be effective in delivering safe water. (SAQ 15.4)

15.1 Public–private partnerships

In the major towns and cities of Ethiopia water is supplied by water utilities (also known as Town Water Supply Enterprises) but public–private partnerships (PPPs) can be helpful. A public–private partnership is any collaboration between public bodies, such as a municipality or even the government, and private companies. The belief is that private companies are more efficient and better run than bureaucratic public bodies, and the management skills and financial acumen that they bring will create better value for money for customers. The incentive for the private companies is the profit that can be generated. PPPs have become popular, to the extent that the number of people served by private water operators in developing and former Communist countries increased from 94 million in 2000 to more than 160 million in 2007 (Marin, 2009). Philippe Marin’s report, Public–Private Partnerships for Urban Water Utilities, which was a review of PPPs in urban water utilities in developing countries, was undertaken because of the interest generated in these arrangements. At the time of the report (2009), about 7% of the urban population in the developing world was served by private water operators. There are different ways in which PPPs can be set up (described later in this study session) but the sections that follow now briefly consider the factors that Marin covered in his report.

15.1.1 Access

Marin found that where most of the investment for expansion of access was provided by the public partner rather than the private operator, access to piped water increased. The finance provided by the public partner is thus crucial if the aim is to increase the number of people with access to water.

15.1.2 Quality of service

Marin reported that often water PPPs substantially improved service quality, in particular by reducing water rationing (for example, in Guinea, Gabon, Niger and Senegal). This had the advantage of improving drinking water quality because a constant flow of water through the piping system reduces the risk of infiltration of unclean water from the soil around the pipelines.

15.1.3 Operational efficiency

The three main indicators of operational efficiency (water losses through leakage, etc., payment collection and labour productivity) were also studied by Marin.

Water losses

Any water lost is a loss in income, and so, perhaps predictably, Marin found (in line with other researchers) that private operators were effective in reducing water losses, some reducing non-revenue water to less than 15% (which Marin states is similar to that of some of the best-performing water utilities in more developed countries).

Can you recall what non-revenue water is?

In Study Session 7 you learned that it is water from which no income accrues to the water utility.

Payment collection

Not surprisingly, because of the financial benefits to the private partner, it was found that the introduction of a private operator markedly improved the payment collection rate.

Labour productivity

There was strong evidence that the introduction of private operators resulted in an improvement in labour productivity. This is the amount of work undertaken by each employee. Many of the public water utilities studied were over-staffed, and the PPPs when set up were followed by significant redundancies, ranging from 20% to 65% of the labour force. Besides the over-staffing issue, layoffs were often motivated by a need to change the overall profile of the workforce and to hire more skilled people (Marin, 2009).

Marin concludes by saying that the biggest contribution that private operators can make in a PPP is in improving operational efficiency and service quality. Improving service quality results in customers becoming more willing to pay their bills, and increasing operational efficiency results in increased income. Both of these factors lead to more money being available for investment in expansion of services. In turn, expansion of services results in more customers and consequently increased income, which again can be invested to bring access to water to even more people.

15.2 Assessing the performance of a PPP

The performance of a PPP (and indeed a public water utility) can be assessed through the following parameters (Athena Infonomics, 2012):

- Accessibility: What proportion of the population have access to water? Is the distance to the water point less than 1 km or 30 minutes’ walking time? Pickering and Davis (2012), using survey data from 26 sub-Saharan countries, found that the further away a water source was, the less water was used; when the distance was more than 30 minutes away, households collected less water than was necessary for basic needs.

- Affordability: Is the cost of the water needed less than 5% of the household’s income?

- Cost recovery: Is the cost of providing the water being recouped?

- Minimisation of non-revenue water: Is this reduced to no more than most 15%?

- Water quality: Is there adherence to national standards?

- Operational efficiency: What is the quantity of water supplied per capita? What is the duration of water supply in hours per day?

These parameters can be used to evaluate whether a PPP is beneficial, with data from before the partnership’s creation being compared with data after the PPP has been running for, say, a year.

15.3 PPP for bill payment

In Ethiopia, a public–private partnership called ‘Lehulu’ (which means both ‘for all’, and ‘for all services’, in Amharic), established jointly by the Ethiopian Ministry of Communications and Information Technology and a private company, was launched in early 2013. Its remit was to allow easy payment of bills from the Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation (EEPCO), EthioTelecom, and Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority (AAWSA). Based on the ‘build–own–operate–transfer’ model, this was said to be the first such institution in Africa, and has the potential to create more than 450 jobs (Kifiya Financial Technology, n.d.). In the build–own–operate–transfer model of PPP, a private firm sets up a system, owns and runs it for several years, and then transfers it to the public sector.

The one-stop facility is available in various parts of Addis Ababa and other towns. Customers can save time, energy and transport costs by paying all three of their bills in one location, instead of having to go to three different payment points. At launch there were 31 Lehulu centres in Addis Ababa, with plans to expand to other towns such as Mekele, Bahir Dar, Hawassa and Adama. Addis Ababa has 2.1 million transactions per month and 1.1 million bill-paying customers (Anon., 2013a), and the payment centres have extended opening hours, from 8:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. on Mondays to Fridays, and from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on Saturdays (Kifiya Financial Technology, n.d.). For each bill processed, the private company running the system receives 2.54 cents (Anon., 2013b). There are plans to make the system accessible online and via mobile phones so that payments can be made without the customer actually going into one of the payment centres. This will save even more time and energy.

15.4 Other possibilities for PPPs

According to François Munger (2008) the most common public–private partnership arrangements in the water sector in developing countries take the following forms:

- Management contracts, where the private firms look after the management, operation and maintenance of the entire water system or part of it (for example, the distribution network) for a limited period of time (approximately five years) in exchange for a performance-related fee.

- Lease contracts, where the private firms maintain and operate the water supply system, at their own risk, deriving revenue from the water tariff, for a fixed period (six to ten years). Investment is financed and carried out by the public sector.

- Concessions, where the private firms provide a service at a given standard for a fixed time (20 to 30 years). The private firms operate, manage, and make the investments, carrying the commercial risks. For example, in countries where hand pumps are common, a private company may take on the role of supplying pump mechanics and spares to keep hand pumps operational.

- Build–own–operate–transfer contracts, as mentioned earlier, are where private firms construct new water treatment plants and run them for a number of years before handing them over to the public sector.

As you can see, there are several different models of PPP.

Can you recall an example of a build–own–operate–transfer PPP?

The Lehulu PPP is an example of such a model.

15.5 Microenterprises

A microenterprise can be defined as a small business that employs fewer than ten people and is started with a small amount of capital. Water supply is an area in which microenterprises operate in a number of different ways, as you will discover in this section.

15.5.1 Selling water at public taps

Public taps (Figure 15.1) are one way of distributing water. The water is sold to people by volume, and customers come to the public tap with water containers. Although many of the public taps are owned and run by the public utility, some are microenterprises: the water is bought from the water utility by the tap attendant and then sold on to consumers at a higher price. A survey of public taps in Addis Ababa (Howard, 2005) found that water was being sold at a price up to eight times the cost of buying directly from the water utility! Public taps are open for only a few hours each day, which can sometimes result in long queues.

15.5.2 Selling water using tankers

Private sellers also supply water through the use of water tankers (Figure 15.2) licensed by the government. This happens in areas not served by a piped water distribution system. The tanker usually has a capacity of 20,000litres and the water is pumped into water storage tanks at the households, which usually have a capacity of about 3000 litres.

15.5.3 Water vendors

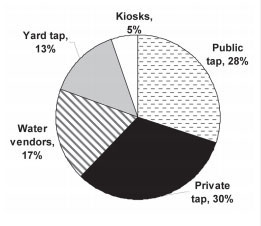

In a survey of three poor areas of Addis Ababa (Sharma and Bereket, 2008), it was found that 17% of the respondents (Figure 15.3) obtained their water from water vendors who had originally purchased the water from the public water utility (the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority). The water vendors in cities are usually people who have private taps in their homes or yards and who sell water from these. The price at which the vendors sold the water to the end users was again about eight times the price paid for the water, corroborating the findings of Howard (2005). Sharma and Bereket found in their survey that most people would have preferred to have their own private tap but the high initial cost of a private connection was prohibitive. If this could be paid in small instalments, 90% of those keen to acquire a private tap would take up the option. In Kombolcha, in Amhara Region it is possible to do this, with the set-up cost being paid in four instalments. There is scope for a private–public partnership here, with private companies providing the administrative arrangements to collect the instalments.

There are also water vendors who sell water from horse-drawn or donkey-drawn carts (Figure 15.4).

15.5.4 Selling water at kiosks

Sharma and Bereket (2008) found that the price of the water at kiosks (Figure 15.5, which were described in Study Session 7) was about three times the cost of water from the water utility. Water kiosks are common in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, and water is brought from the kiosk owner’s home to the kiosk and sold. Alternatively, if the kiosk is near the home of the owner, a hose connection to the house tap enables water to be sold direct. In a typical day a kiosk can serve 500–3000 people bringing their own water containers.

15.5.5 Selling water-related services

As part of the water industry, several microenterprises have emerged to supply plumbing services such as fixing leaks, extending pipelines around a house or compound, and selling and installing plumbing systems (such as tanks, pipes, latrines, WCs, etc.) (Figure 15.6).

Summary of Study Session 15

In Study Session 15 you have learned that:

- It is possible to obtain water from entities other than public utilities.

- One such possibility is a public–private partnership, where private companies collaborate with a public body to provide water services. These partnerships have the potential to bring about a more efficient service.

- Microenterprises are small businesses with fewer than ten staff members.

- In the water sector in Ethiopia, microenterprises operate some of the public taps, as well as undertaking tanker deliveries, water vending and water kiosk management.

- Microenterprises can also be set up for water-related services, such as plumbing and supplying equipment.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 15

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these.

SAQ 15.1 (tests Learning Outcome 15.1)

Match the following words to their correct definitions.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 3 items in each list.

microenterprises

public–private partnerships

labour productivity

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.small businesses with fewer than ten people working in them

b.the amount of work that each employee does

c.a collaboration between a public body and private companies

- 1 = a,

- 2 = c,

- 3 = b

SAQ 15.2 (tests Learning Outcome 15.2)

From the report by Marin (2009) on public–private partnerships, which of the following statements are false? Give reasons why they are so.

- A.A public–private partnership always results in more people having access to piped water.

- B.Public–private partnerships often result in improved service quality.

- C.Public–private partnerships are very efficient at collecting payments but don’t worry about non-revenue water.

- D.In public–private partnerships labour productivity increases, due only to reduction in staff numbers.

- E.The figures indicate that public–private partnerships are becoming more popular.

Answer

A is false. Increased access comes about only when the public partner invests the money.

C is false. Because they are concerned about income, public–private partnerships pay a lot of attention to reducing non-revenue water.

D is false. Labour productivity increases due to two factors: a reduction in staff numbers and an increase in the number of customers.

SAQ 15.3 (tests Learning Outcome 15.2)

List and briefly describe the measures by which the success or otherwise of a public–private partnership providing water supply services can be assessed.

Answer

The following criteria may be used to measure the success of a PPP providing water supply.

- a.Accessibility – the extent of coverage of the population, and the distance to the water point.

- b.Affordability – the cost of the water needed should be less than 5% of the household’s income.

- c.Cost recovery – the cost of providing the water should be claimed back from the population.

- d.Minimisation of non-revenue water – this should be reduced to 15% or less.

- e.Water quality – the water should meet national standards for quality.

- f.Operational efficiency – the quantity of water supplied per capita, and the duration of water supply per day.

SAQ 15.4 (tests Learning Outcome 15.3)

- a.Name two types of microenterprise that supply water to poor people in Ethiopian towns and cities.

- b.What is the main disadvantage that these consumers face?

- c.According to Sharma and Bereket (2008), what would help to overcome the above disadvantage?

Answer

- a.The microenterprises concerned are water kiosks and water vendors.

- b.The main disadvantage consumers face is the high cost of the water.

- c.This disadvantage can be overcome by assistance provided to the consumers to obtain their own private water connections.