Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 11 March 2026, 3:52 PM

Study Session 11 Integrated Solid Waste Management

Introduction

In Study Sessions 7–10 you learned about the composition of solid waste and the options for treating or disposing of wastes. None of the techniques and technologies that we looked at can on their own treat every type of solid waste; they need to be used in combination. This study session introduces the idea of Integrated Solid Waste Management, where a combination of methods are used to manage solid waste in a way that is best for people, communities and the environment.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 11

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

11.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 11.1)

11.2 Explain what is meant by integrated solid waste management. (SAQ 11.2)

11.3 Outline the reasons for shifting from a traditional to an integrated solid waste management strategy. (SAQ 11.3)

11.4 Identify ways of encouraging and supporting an integrated waste management approach. (SAQ 11.4)

11.1 What is Integrated Solid Waste Management?

Think back to previous study sessions and remind yourself what you understand by the following terms:

- waste reduction

- reuse of waste

- waste recycling.

Waste reduction means avoiding producing waste in the first place. In manufacturing industry, it is about using less raw materials to make a given product. In the home, waste reduction could include avoiding buying over-packaged products.

Reuse happens when something is used more than once for its original purpose – perhaps refilling a drinks bottle with water.

Recycling is the reprocessing of materials recovered from waste so that they can be used as raw materials in manufacturing processes, for example melting of glass bottles and forming them into new bottles. You may also have mentioned composting which is classed as a form of recycling.

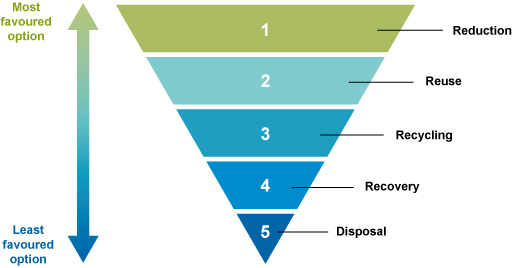

By now you are familiar with the waste hierarchy, which is shown again in Figure 11.1. In the past few study sessions, we have discussed all the options in the hierarchy from the most desirable (reduction) to the least desirable (disposal).

Unfortunately, many towns and cities are not able to follow the waste hierarchy and the only option used is disposal. Much of the waste is never collected (it is dumped or burned) and even where it is collected, most of the waste is taken to a landfill that has no means of controlling pollution from the site. Case Study 11.1 about the town of Jimma illustrates this situation.

Case Study 11.1 Waste management in Jimma: an example of current practice

In 2011, Jimma had a population of around 160,000; this had grown to 200,000 by 2014. Solid waste generation in 2011 was 88 metric tons per day with 87% of this being waste from households.

A total of 25% of households deposited their waste in communal containers that were then taken to landfill; 51% used disposal pits, their own back yards or open dumping of waste in public spaces; 22% burned their waste in public open spaces; and the remaining 2% of households had waste collected by private sector organisations. There is no formal system for collecting wastes for reuse or recycling.

Waste management is the responsibility of the municipality’s Social and Economic Department who employ 33 waste workers. The department has one tipper lorry for waste collection purposes and ten metal bins for commercial waste storage, each with capacity of 4 m3 that are placed randomly in residential and commercial areas. The budget for waste is less than 1% of the total municipal budget. Staff wages take up 90% and the remainder is spent on fuel, maintenance and other running costs.

The situation in Jimma is typical of many towns in Ethiopia. This session looks at how towns like Jimma can adopt the principles of Integrated Solid Waste Management to move their waste management systems further up the hierarchy and reduce the risks of damaging people’s health and the environment.

Integrated Solid Waste Management (ISWM) can be defined in many ways but it is probably best to think of it as a way of using a combination of waste management techniques to treat the different types of waste in ways that are environmentally, financially and socially sustainable. ISWM should be based on the waste hierarchy and focus on using the 3 Rs while finding a suitable way of dealing with the remaining waste. It also depends on collaboration among all the organisations and individuals involved in waste management.

Van de Klundert and Anschütz (2001) explain that the ISWM concept is built upon four basic principles:

- Equity: the allocation of resources, services and opportunity to all segments of the population according to their needs. In waste management this means thateveryone has a right to be served by a waste management system that protects their health and the environment. Pollution travels and doesn’t respect kebele or area boundaries, so if one area is neglected, a much larger area can suffer.

- Effectiveness:the waste management methods used must meet the overall aims of any waste plan and meet the needs of the people. At the very least, effectiveness means that all the waste is collected and disposed of in a safe way. Once this has been achieved, higher-level aims such as maximising waste recycling and composting should be addressed. Again, a scheme is only effective if it covers the whole of the kebele, city or district.

- Efficiency: in general, efficiency means increasing output for a given input, or minimising input for a given output. An efficient waste management system is one that is equal and effective while making the best use of the resources available (staff effort, use of equipment and cost).

- Sustainability: for a project, programme or other activity to be sustainable it must be effective and last a long time. To achieve sustainability social, environmental and economic factors must be considered. Sustainability of the waste management system can be achieved if it is appropriate to the local conditions and can continue in the long term by using the human, financial and material resources available in the area. It should also be environmentally sustainable in that it minimises the use of non-renewable natural resources (such as oil) and doesn’t lead to long-term environmental problems that will be left for later generations to address.

Which of the following waste management systems meet the four conditions of ISWM?

- a.Waste is collected from households that can pay a weekly fee; those who can’t pay use informal methods of waste disposal.

- b.A network of korales coordinated by the kebele collect recyclable materials (glass, paper and metals), householders take the remaining waste to communal bins (one per 30 households) which are emptied by the kebele’s contractor who takes the waste to landfill.

- c.Waste is collected from households in well-off areas by charging a weekly fee; in poorer areas the waste is collected from communal bins by kebele employees.

- d.Under a grant from an aid agency that will run for two years, a kebele’s waste is collected, taken to a transfer station and then driven 20 km to a landfill site that is also funded by the grant.

Options (b) and (c) do broadly meet these conditions (although we should find out more about the standard of the landfills).

Option (a) does not meet the criteria of equity or effectiveness.

Option (d) is good for the environment and people’s health but is not financially sustainable.

11.2 The advantages of ISWM

Introducing ISWM means adopting all of the beneficial practices that have been described in previous study sessions and ensuring that they all work together effectively. It has a number of advantages for the different sectors of society. Here are some examples:

- Reduction and reuse at source – reducing waste at the source and reusing wastes means that less waste has to be collected. This lowers costs for residents, businesses and the local authority. Also, the pollution generated in transporting the waste and at the disposal site is reduced. Waste reduction and reuse means that there is less pollution from manufacturing and a reduced need to import goods. Finally, society benefits because people have the use of items that they may not otherwise be able to afford.

- Waste separation at source – many ISWM schemes require householders and businesses to separate reusable and recyclable materials from the rest of the waste and sort them by type (Figure 11.2). This helps to make people more aware of what they throw away and means that the material separated for recycling is of a higher quality and has a higher selling price. In alternative schemes, where recyclable materials are extracted from mixed wastes at the transfer station, there is a greater health risk to those who do this work and also to those who work in the recycling industry.

- Recycling – like reduction and reuse, recycling has benefits outside the waste management system. Recycling reduces the need to extract raw materials from the ground or to import them. Producing metals, glass and paper from waste materials rather than raw materials consumes far less energy. Also in common with reduction and reuse, recycling means less waste is sent to landfill, giving further reductions in pollution.

- Organic waste recovery – composting organic waste is a form of recycling (see Study Session 9) and has similar benefits to other recycling processes. The amount of waste sent to landfill is reduced and the compost can be used locally to improve soils and the crops grown on them. Organic waste can also be used in anaerobic digesters to produce biogas for cooking and lighting.

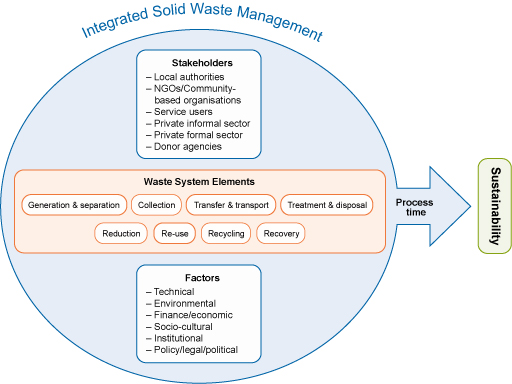

11.3 The components of ISWM

An ISWM system is more than just the 3 Rs. It has three components: the waste system elements; the stakeholders; and the influencing factors. These three components are shown in Figure 11.3. The waste system elements are the stages in the waste management chain that have been discussed in previous study sessions. In ISWM, every stage in the chain should be guided by strategies to minimise the waste that reaches the disposal site, to protect the environment and where possible to generate income from waste. The stakeholders are the people and organisations involved and the influencing factors are other aspects that need to be considered when developing an ISWM system. Stakeholders and the influencing factors are described below.

11.3.1 Stakeholders

The term stakeholder refers to any individual or organisation that has a stake or an interest in a programme or activity or is affected by the activity. When it comes to the management of a kebele’s waste, who are the stakeholders? Everybody who lives or works in the kebele is a stakeholder. So are people who visit the kebele for any reason (perhaps relations of residents). The organisations in the kebele are also stakeholders (businesses, commerce, government etc.). If a private sector organisation is involved in providing the service, it too is a stakeholder. The organisations that provide any funding for the ISWM (local and national government, NGOs, aid agencies) are also stakeholders. This is such a wide group because every person, institution, organisation and industry in the kebele generates waste and is affected by the way it is collected, treated and disposed of.

Waste management requires a concerted effort throughout the process of its management and the degree of involvement of stakeholders varies from place to place. So it is necessary to identify stakeholders and their areas of interest and degrees of involvement in waste management (e.g. funding, training, waste collection, recycling etc.).

List the stakeholders in waste management in your home village, town or city.

Your list will depend on where you live but could include:

- households, individuals, businesses and other waste producers

- kebeles and municipalities

- urban health bureaus

- micro- and small enterprises

- city greening, beautification and parks development agencies

- private sector organisations engaged in waste collection, transfer and transport

- korales

- waste pickers

- dealers who buy and trade in recyclable wastes

- end-user industries that buy recyclables

- NGOs.

One of the main challenges of ISWM is coordinating the stakeholders and getting them to work together for a common goal. So those working in waste management need to be able to work with the various stakeholders and help them to agree the way forward. Participation by the community members in planning and decision making is especially important because their cooperation and a positive attitude to recycling and reuse will be essential.

11.3.2 Influencing factors

Several factors will influence the selection, operation and effectiveness of any waste management scheme and need to be considered when planning a successful ISWM programme. They include:

- Technical factors – refer to the selection of technologies that are available and will function with the quantities and composition of the waste produced. For example, the technology designed to compost one ton of waste a day will not be suitable for processing 50 tons per day. The reliability of the technology needs to be taken into account; it must operate under Ethiopian climate conditions and be repairable using locally available materials and people.

- Financial factors – are aspects that deal with budgeting and costs of the waste management system. Some of the most important issues to consider are the effect of private sector involvement and recovering the cost of the system from residents, businesses and government. The impact of the market prices of recovered materials, the amount and source of any subsidy to cover collecting wastes from those who cannot pay, and any other income-generation schemes also need to be considered.

- Environmental factors – focus on the effects of waste management on land, water and air, the need for conservation of non-renewable resources, pollution control, and public health concerns (Figure 11.4).

- Political and legal factors – refer to the administrative context in which the waste management system exists; the goals and priorities that have been set; the determination of roles and responsibilities; the existing or planned legal and regulatory framework and the decision-making processes.

- Socio-cultural factors – include the influence of culture on waste generation and management in the household and in businesses and institutions, the community and its involvement in waste management; the relations between people in the community of different age, sex and ethnicity; and the social conditions of waste workers.

11.4 Applicability of ISWM

Integrated solid waste management can be planned for big cities such as Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, Bahir Dar, Hawassa, Mekelle and Adama or medium-sized cities such as Jimma, Nekemte, Dessie and Assela, or small towns like Wolkite, Wukro, Debre Birhan, Bedele and Maksegnit. Although the principles used are the same, some of the waste system elements are more applicable in particular sized communities as shown in Table 11.1.

| Waste management component | Big cities (population above 200,000) | Medium cities (population 100,000–200,000) | Small cities (population less than 100,000) |

| Reduction at source | Highly applicable | Highly applicable | Highly applicable |

| Sorting at household level | Applicable but not yet introduced as part of the formal waste system but could be done if sufficient start-up funding was available Some segregation takes place through the korales | Applicable but not yet introduced as part of the formal waste system but could be done if sufficient start-up funding was available and if the cities are close enough to manufacturers willing to take the materials recovered Some segregation takes place through the korales. | Applicable but not yet introduced, sorting would probably be limited to separating compostable wastes Some segregation takes place through the korales |

| Reuse of items | Highly applicable | Highly applicable | Highly applicable |

| Recycling | Highly applicable | Applicable if linked to big cities Can be promoted through small-scale recycling (paper for example) | Applicable and can be promoted through small-scale recycling (paper for example) |

| Composting | Applicable and can be scaled up at material-processing and energy-recovery facilities Can be scaled up by using the private sector/small-scale enterprises with subsidy | Applicable and can be scaled up by using the private sector/ small-scale enterprises with subsidy | Applicable and can be scaled up by creating awareness and by organising small-scale enterprises |

11.5 Encouraging ISWM

In the previous sections, we have explained the many benefits that ISWM brings to a community. ISWM helps to safeguard public health, improve the environment and gives a better image to the city. Hence improving waste services is a priority for many stakeholders – the government, NGOs, health and environment ministries and city councils.

However, developing and implementing ISWM needs start-up capital and an on-going revenue scheme. It needs investment in equipment and in the training and development of skilled staff. ISWM also requires effort from all the stakeholders. Therefore, it is sometimes necessary to encourage people to develop and implement ISWM by providing incentives. These incentives may be financial benefits or the offer of some other sort of reward for adopting an ISWM approach.

It is at the local level where encouragement and incentives need to be provided. This is a task for national or local government and can take a number of forms. For example:

- National government could allow municipalities that perform well in terms of waste collection and treatment the flexibility to spend more of their budget on waste services if it can be shown to achieve savings in other areas.

- Where good practice in waste management has been demonstrated, special funds could be allocated to allow this practice to be extended within an area or replicated in other areas.

- Local authorities could reward best performing individuals, institutions or environment clubs through various mechanisms including media coverage and awards.

- Financial support could be given to environmental groups and small-scale private sector enterprises that engage in waste collection, composting and recycling. This support could be provided through the savings achieved by the municipality in its collection, transport and disposal costs.

Even when incentives are provided, attempts to improve the waste management system are not always successful as shown in the following case study. Read the case study and then answer the questions below.

Case Study 11.2 Why do composting programmes fail? The case of Jimma

Jimma city administration organised a group of young people to become involved in waste composting through its job creation policy framework. The youth club members were identified by kebeles and sent to the Environment and Social Affairs Department of the municipality for training. The municipality ‘oriented’ them and provided them with land and basic tools to run the composting programme. These young people were very well motivated and started their job, hoping that they would earn sufficient money to sustain their livelihoods.

The task they were set was not simple. They had to collect compostable waste, separate and remove the waste components they did not need and send them back to the communal collection skips. Unfortunately, their training did not give them the information they needed to be sure about the mix of wastes for effective composting process (for example, whether it needed more leaves, more paper and or more food waste). They also did not know how to monitor the temperature and moisture content of the composting waste. Consequently, the compost took a long time to mature and even after six months they did not have good quality compost.

This youth group were very disappointed with their first batch of compost. They had hoped to sell the compost to local farmers but most of them had no interest in buying it because they had access to synthetic fertilisers distributed by the government. The farmers who did express an interest offered a small amount of money but this was not enough to cover the producers’ labour costs. The youths became frustrated and gave up the scheme.

What are the lessons that can be learned from this case study?

Several things could have been done much better:

- The initial training programme should have been expanded to cover the nature of waste, the types of waste needed to make compost and how to carry out the composting process (balancing the material mixes, how often to turn the compost heaps, how to measure the temperature and moisture content and how to know when the compost is ready for use).

- More equipment should have been provided (at the least, suitable thermometers should have been made available).

- The youths should have been supervised, assisted and guided through the process of making and selling compost for at least the first year to encourage them to keep on doing the job.

- A financial supporting mechanism should have been established for at least an initial period until markets for the compost had been established and money started to flow in.

- Markets for the compost should have been identified beforehand.

From your study earlier in the Module, what specific information should the young people have been given about the required mix of brown and green waste for composting?

They should have been told to mix three parts of brown waste (paper, woody material, dried vegetation) to one part of green waste (food waste, animal manure, fresh vegetation).

Developing and implementing an ISWM system is a significant task that requires commitment and the cooperation of many stakeholders as well as financial investment. Its success will depend on continuing support from the community. As someone involved in promoting improved sanitation, you may find yourself working with a team charged with introducing an ISWM system. The sort of tasks that you could be doing include:

- helping to educate the public on the advantages of introducing the 3 Rs and the basic principles of integrated solid waste management

- working closely with the health sector and labour and social department of the municipality to protect the health of korales and others in the informal waste management sector

- identifying potential stakeholders in the town

- assessing the situation in and around the town and deciding with other stakeholders whether it is possible to introduce ISWM.

In Ethiopian towns, there is increasing focus on solid waste management. Adopting an ISWM approach that brings together the most effective technologies and has the support of all stakeholders will ensure that sustainable improvements are made which will benefit the communities and the environment.

Summary of Study Session 11

In Study Session 11, you have learned that:

- Integrated waste management is built upon the 3 Rs –reduce, reuse and recycle – and on the waste hierarchy.

- ISWM involves using a combination of waste management methods to achieve the best waste management solution.

- ISWM builds on the four principles of equity, effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability.

- ISWM has three components: the waste system elements; stakeholders; and influencing factors.

- ISWM can be applied to towns and cities of all sizes but the details will vary depending on the population size and amount of waste produced.

- Implementing ISWM requires resources and investment in equipment and staff training. It may be necessary to offer incentives to encourage municipalities and others to develop an ISWM system.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 11

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions.

SAQ 11.1 (tests Learning Outcome 11.1)

Rewrite the paragraph below using terms from the list provided to fill the gaps.

effective (more than once!), efficient, equity, sustainable.

The waste management system should ensure everyone in the community can benefit from the service provided. This is the principle of ……………… An ……………… system will function well and meet the needs of all the people. It will also be ………………, which means it will make the best use of available resources and ………………, meaning it will continue to be ……………… into the future.

Answer

The waste management system should ensure everyone in the community can benefit from the service provided. This is the principle of equity. An effective system will function well and meet the needs of all the people. It will also be efficient, which means it will make the best use of available resources and sustainable, meaning it will continue to be effective into the future.

SAQ 11.2 (tests Learning Outcome 11.2)

Explain why Integrated Solid Waste Management is described as ‘integrated’.

Answer

ISWM is described as integrated because it is a combination of different approaches. Rather than just recycling, for example, or any other single approach, ISWM depends on using many of the methods of waste management together. It is also integrated in the sense that it requires all stakeholders to work together in a collaborative way to achieve the goals of improved solid waste management.

SAQ 11.3 (tests Learning Outcome 11.3)

Which of the following statements are false? In each case explain why it is incorrect.

- A.ISWM has benefits for public and environmental health.

- B.ISWM is a simple, inexpensive approach to waste management.

- C.ISWM reduces the amount of plastic and other waste dumped in the streets.

- D.ISWM reduces the lifespan of the local landfill site.

- E.ISWM provides opportunities for production of compost and other valuable materials.

Answer

B is false. ISWM has many advantages but it is a complex long-term approach that needs financial and other resources.

D is false. ISWM will reduce the quantity of waste that goes to the landfill site because some will have been removed for reuse or recycling. Less waste means that the landfill site will take longer to fill up so its lifespan will be extended, not reduced.

SAQ 11.4 (tests Learning Outcome 11.4)

Give three examples of ways of encouraging or supporting an ISWM approach.

Answer

You may have mentioned any three of the following possible ways of encouraging and supporting ISWM:

- the national government can allow greater flexibility in budget spending by municipalities

- extra funds may be allocated to adopt or extend ISWM

- start-up funding can be provided for new initiatives such as waste collection, composting and recycling schemes

- special awards could be given to individuals and organisations to celebrate successful projects

- providing effective training for people who wish to start new schemes and supporting them in the early stages of development

- organising promotional campaigns to raise awareness of the 3 Rs among all members of the community.