Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 7 February 2026, 5:34 AM

Mental health awareness

Introduction

Mental health care has been described as ‘a family affair’ because modern support services are increasingly focused on community settings, where most mental health care now takes place. According to the Office for National Statistics (2010), there are 1.5 million people in the UK caring for a relative or friend with a mental health problem or dementia. There is an increasing emphasis on the role of family caregivers in supporting recovery for people in mental distress.

The course is of value to all carers. Carers for people with mental health problems can include people looking after a relative or a friend in their home. They might also include people who are paid to care, such as support workers in community-based services. We also recognise that in some situations the ‘cared-for-person’ might have some caring responsibilities and that informal and paid carers might also need looking after at times.

In this section you will develop an awareness of mental health problems. You will look at care and treatment options for individuals who are diagnosed with one of a range of mental illnesses. You will then study the role of family carers looking after a friend or relative with mental health problems, and their relationship and engagement with mental health services.

At the end of the section there is a short quiz to test what you have learned. On successful completion of the quiz you will earn a digital badge.

This section is divided into five topics and each of these should take you around half an hour to study and complete. The topics are as follows:

- Terminology and mental health discusses the difference between good mental health and mental health problems. It introduces the biomedical model as an approach to care and treatment and outlines some of the shortcomings of this model.

- Types of mental health problem describes signs and symptoms of specific mental health problems.

- Experiencing mental health problems explains how mental health problems can affect the individual.

- Mental health care and treatment outlines how mental health care aims for recovery and discusses specific treatment for particular types of mental health problems.

- Carer experience discusses the impact of mental health problems on family carers and how family carers can engage with mental health services.

Learning outcomes

By completing this section and the associated quiz, you will be able to:

describe the main types of mental health problem and how they might affect the cared-for person

explain the impact mental health problems might have on family carers.

1 Terminology and mental health

In the introduction to this section of the course you will have noticed that a number of different terms are used to describe the experience of people who for one reason or another have been associated with mental health issues. These issues are described as mental health problems, mental ill-health and mental illness. Other ways to describe mental health problems include mental disorder, mental disability, mental distress and mental incapacity. Many people understand mental health problems because of specific conditions. Later in this section you will learn about some of the types of mental health problems, including:

- depression

- schizophrenia

- bipolar disorder

- dementia.

In this course we are using the term ‘mental health problems’ because it suggests that the condition brings with it wider issues than an individual’s mental health status implies. Note the term ‘mental health problems’ is used in the plural. The person can often have more than one problem associated with their condition.

Activity 1

Consider what you think is meant by good mental health and how it might differ to having mental health problems. Jot down your thoughts in the box below.

Comment

The difference between having good mental health and experiencing mental health problems is a contested area. Good mental health is not just the absence of mental health problems. It is, instead, a positive state of well-being in which the individual

- is able to make the most of their potential

- copes with the everyday things that happen in life

- can play a full part in the lives of others.

However, many people with mental health problems argue that they can attain their potential, cope with life and enjoy fulfilling relationships as long as their particular needs are met. Others, of course, do not enjoy this positive state of mental health and require ongoing care and treatment.

1.1 The biomedical model

The most common way to understand mental health problems is by seeing them as an illness in the same way as other health problems, such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes, are seen as illnesses. Policymakers encourage us to do this. Underlying the biomedical model is the belief that mental illness has a cause that can be treated and, in many cases, the patient cured.

The biomedical model has its advantages:

- It offers explanations of mental ill-health that many people who experience mental health problems find reassuring as it can be the first stage towards recovery.

- Diagnosing and naming conditions can help to reassure people that what they experience is ‘real’ and shared by others.

- Relieves symptoms such as hallucinations, a rapid heartbeat or constant worrying so that the individual starts to feel better.

- Provides access to help and support that can help to alleviate some of the things that trouble the individual, such as not being able to go shopping.

However, the biomedical model is founded on the assumption that:

- the cause of the mental illness lies within the individual so the focus of treatment is on bodily symptoms

- there is a focus on what is normal so that medical judgements determine what is not normal.

The biomedical model has shortcomings that a more holistic model might explain.

A holistic model of mental health takes into account the physical, spiritual, psychological, emotional, social and environmental components of our lives. In other words, it takes into account our person and everything about our life as a whole.

1.2 Stigma and discrimination

People who suffer from mental health problems often find that the causes of their distress do not lie within them but can be found in the situations in which they find themselves. For example, poor housing on noisy estates where the person feels isolated is more likely to lead to mental health problems than a well-supported home in a quiet and friendly environment. Today, being subjected to prolonged stress from work and the other demands made on people is a major cause of mental health problems.

Traditionally, people have tended to see others with mental health problems as being different. The result is that those with mental health problems have become cut off from the ‘normal’ social life that most people take for granted, such as good employment opportunities and wide social networks. This can also lead to two particularly damaging consequences: people with mental health problems can experience stigma and discrimination.

Stigma

Due to stigma, people with mental health problems are disapproved of. They are not seen as a person in their own right, but only as having a mental illness. Stigma can make their mental health problems worse because it isolates them, and consequently the mental health problems are harder to recover from. It is the mental illness that other people see and not the person. In this way people with mental health problems are also discriminated against.

Discrimination

Discrimination is the harmful treatment of an individual or group of individuals because of a particular trait or characteristic. Although the Disability and Equality Act 2010, which applies across Great Britain, explicitly forbids any form of discrimination, people with mental health problems might still experience indirect discrimination. For example, they might be excluded from sports clubs on the grounds that they do not fit in or excluded from up-market shopping malls where their presence or appearance offends consumers. They might also not have their mental health considered when they are at work, for instance being exposed to stressful situations or meeting unrealistic targets.

1.3 The legal framework

In England and Wales mental health practice is governed by two main pieces of legislation. The Mental Health Act 1983/2007 provides the overarching law on how care and treatment is offered, with provision for individuals to be sectioned if necessary. This means they can be made to accept treatment against their will in some carefully regulated circumstances. It is worth noting that most people who use mental health services do so as an informal or voluntary service user, and are not obliged to accept treatment if they do not wish to.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 is used to ensure that vulnerable people, particularly older people who are unable to govern their own affairs, are not exploited or harmed. If this is the case, Power of Attorney can be made so that another person takes on the legal authority to act on behalf of that individual. This often happens when an older person develops dementia and can no longer make decisions, for example to manage their finances or other everyday tasks. If you want to read more about the Mental Capacity Act, see Section 4 of this course, Positive risk-taking.

Scotland has its own mental health legislation: the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 2015. The Mental Health (Northern Ireland) Order 1986 governs care and treatment in Northern Ireland.

It is worth noting that most people who use mental health services do so on an informal or voluntary basis, and are not obliged to accept treatment if they do not wish to do so.

2 Types of mental health problem

Some mental health problems are common and many people with good mental health know what the problems feel like. It is estimated that one in four people will experience mental health problems at some point in their life, while at any one time one in six people will experience mental health problems. The majority of these people have depression or anxiety. Mental health problems are difficult to see; consequently they are not accepted as an illness in the same way as physical illness or disability.

In this section we focus on mental health problems that have an effect on people’s lives in one way or another. You will probably have heard of many of them.

Diagnoses

Before you study types of mental health problems, we’d like you to reflect on any diagnoses that you have heard of or had experience of.

Activity 2

Make a note of any mental health problems that you are aware of.

- What is its/their name(s)?

- What signs and symptoms might the mental health problem lead to?

Comment

Some mental health problems are common and many of the signs and symptoms are a familiar experience to most people. Some of the symptoms, for example, are part of the ‘normal’ way that people react to changes in their circumstances; strong feelings of sadness and guilt during a bereavement is normal, but it is not so normal in the absence of a bereavement. Some mental health problems feature symptoms that are not part of the normal experience for most people; hearing voices and holding odd beliefs about other people are two examples.

You will now consider types of mental health problems as they are classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). It is worth remembering that these are based on medical diagnoses and so are largely based on a biomedical model. When making a diagnosis professionals rely on a combination of signs and symptoms, as well as other information such as that gained from blood tests.

Signs are what another person can observe, whereas symptoms are what the individual experiences or feels. A mental health professional will try to observe for signs or ask another person known to the individual to talk about any signs they have observed, and seek information from the individual about their experience by questioning them during mental health assessment.

Classifications of mental health problems and their common signs and symptoms are described next.

2.1 Mood disorders

Mood disorder does not just refer to whether you are angry (in a bad mood) or understandably happy at hearing good news (in a good mood). Rather, mood refers to the individual being in despair and very sad (low in mood) or ecstatically happy and elated (high in mood).

Being in a good mood or being in a bad mood are common human emotions and we all have experienced them at one time or another. However, when there is an extreme tendency where a person’s mood is very low or very high for a prolonged time, then it might be due to diagnosable mental health problems. Disorders of mood include depression, mania and bipolar disorder.

Depression

When an individual is in a very low mood they are termed depressed. Signs and symptoms of depression include:

- Changes in appetite: the individual might eat more than usual or lose their appetite completely. Weight gain or weight loss results.

- Sleep changes: the individual is likely to have trouble getting off to sleep or is waking in the early hours. In the morning they will not feel refreshed and will feel tired most of the day.

- Feeling sad (crying a lot), without hope, and feeling guilty much of the time. Signs to other people include the individual seeming very negative in outlook and lacking motivation.

- Feeling tired, overwhelmed and pressured, lying in bed and isolating oneself.

Mania

Mania is rare but does occur at times. Typically, a person who is in a manic state might display the opposite signs and symptoms to a depressed person.

- The individual might be very active, or even overactive, so that they lose weight through missing meals or exercising excessively.

- The individual might be seen by others as overenthusiastic, over joyful and ecstatic even if there is no obvious reason for such high emotions. At times it can result in recklessness and not considering the consequences of their actions properly.

- The individual might complain that their thoughts are rushing so that they cannot concentrate on a task for very long and are easily distracted.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder used to be known as manic depression. Individuals who have bipolar disorder experience the highs of mania alternating with the lows of depression.

2.2 Anxiety disorders

When a person has a panic attack they breathe fast and deep, exhaling a lot of carbon dioxide (CO2) so they will feel faint. If they blow into a paper bag and then re-breathe from the paper bag they take in some of the CO2. It helps to slow down the breathing so the person feels better.

As the name suggests, anxiety disorders occur where the person feels unusually anxious, either in the short term or for a prolonged period. There are several types of anxiety disorder:

- General anxiety disorder in which the person feels fearful or anxious for a long time but without any obvious cause.

- Panic disorder in which the person has panic attacks that can be unpredictable.

- Phobias, which are an intense fear of something that triggers anxiety.

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), which causes the person to have intrusive thoughts or urges to do something, such as clean excessively, and an overwhelming desire or compulsion to repeat tasks such as check locks or flush the toilet.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety associated with a bad experience in which the person relives the fear and anxiety that they felt during that bad experience.

2.3 Psychosis

Psychoses are a group of serious mental health problems where the individual loses touch with reality. This experience is not something that most people can identify with and so the behaviour of an individual who is psychotic can seem very odd. The best-known type of psychosis is schizophrenia. A diagnosis of schizophrenia in most cases means that the individual is referred to specialist mental health services.

Schizophrenia

Many people think of people with schizophrenia as having a split mind. This is not the case. It does mean, though, that many people who have schizophrenia lose some of their personality – it is described as ‘fragmented’. This is largely due to the way schizophrenia affects people. The effects of schizophrenia are broadly divided into so-called positive symptoms and negative symptoms.

Positive symptoms are named positive, not because they are necessarily a good thing but because they add something to the person. For example, a diagnosis of schizophrenia is usually made when certain symptoms are present – that is the symptoms are added to the person.

There are typical examples of positive symptoms that are indications of psychosis and schizophrenia. The individual might display odd behaviour as a response to symptoms including hallucinations, delusions or other disordered thought processes.

- Hallucinations are sensory perceptions where there is no external stimulus. For example, an auditory hallucination such as hearing voices occurs when there is nobody speaking.

- Delusions are strongly held beliefs that other people don’t share. For example, the individual might believe that their neighbour can read their thoughts.

- Thought disorders include thinking that the television news is referring to that individual specifically or that the individual thinks that other people can control them through special cognitive powers.

In schizophrenia the individual might also feel very lethargic, unmotivated and seem to others disinterested in what is happening around them. They might be unable to look after their immediate environment without prompting. These are examples of the negative effects of schizophrenia – they take away from the individual.

2.4 Dementia

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a wide range of cognitive disorders. In cognitive disorders the individual loses their ability to think and might even lose their memory completely. Complete amnesia is very rare but the most common and prevalent type of cognitive disorder is dementia. The best-known type of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease. It is found mainly in older people but it can occur much earlier as a pre-senile dementia. Other well-known types of dementia are vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia and dementia with Lewy Bodies.

Features of dementia include:

- gradual memory loss

- inability to think through problems in everyday life

- inertia (inactivity)

- losing the ability to communicate and interact appropriately.

The Alzheimer’s Society has useful information about dementia, such as diagnosis and caring for a person with dementia.

2.5 Other disorders

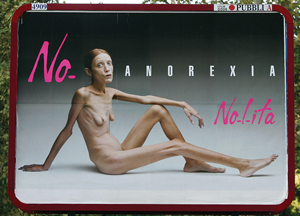

Eating disorders

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia are the best-known eating disorders. While they are often associated with young women and adolescent girls, each can occur in both genders and throughout the age range.

In anorexia the individual aims to lose weight. They will eat very little and purge their body (through vomiting or taking laxatives) to do so. It is thought that disordered body image and views about food and appearance cause severe weight loss. In contrast, individuals with bulimia are likely to binge eat before purging the body, for example by making themselves vomit.

Personality disorders

This is often referred to as BPD – Borderline Personality Disorder. It describes individuals who demonstrate challenging or anti-social behaviour caused by their disordered thoughts. Individuals might have poor coping skills, so that they get easily frustrated with life challenges, which in turn can lead them into prolonged conflict with family and friends. Due to the difficulty in forming proper relationships, many might self-harm repeatedly and are often described as attention seeking.

Substance-related disorders

Individuals who might be classified as having a substance-related disorder are dependent on drugs, alcohol or other addictive substances. Sometimes freely available drugs, including so-called legal highs, can contribute to mental health problems. Substance misuse can cause both physical and mental health related problems. If there is substance use or alcohol abuse in conjunction with other mental health problems such as schizophrenia, it can increase the severity of the symptoms. This is usually referred to as dual diagnosis, where specialist services for substance misuse and mental health problems are both involved in the care and treatment of the person.

The types of mental health problems we have described suggest that classifications are clear-cut but this is not always the case. Sometimes the differences between them are blurred. To better understand how mental health problems affect individuals we would like you to now turn to the personal experience of two people who have lived with mental health problems.

3 Experiencing mental health problems

An understanding of the effects that different types of mental health problems might have on the individual is best gained by hearing what people who live with mental health problems say about their experiences.

You will now watch a short video by the actor and TV presenter Stephen Fry who articulates the numbing effect his bipolar disorder can have. Note that the video is titled manic depression and not bipolar disorder, reinforcing that terms change as our understanding and ideas about mental health problems evolve.

Activity 3

View the video The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive Part 1.

Transcript: Stephen Fry talks about his depression

The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive Part 1

As you watch the video make brief notes on any signs and symptoms that Stephen Fry describes.

Comment

Fry talks about his frustration and misery as he describes the effect that his bipolar disorder has on his life. In the video he focuses on the depressive features of his mental health problems. You will have seen how he suffered; he wanted to be alone, he felt guilty that he had let other people down, and felt a tremendous sense of misery and failure. He doesn’t discuss the reckless and impulsive behaviour during the manic phases he has also experienced. If he had, he might have told of his shoplifting sprees and of how he was on the run from the police. It was when he was a young offender in prison that he was first diagnosed as having mental health problems.

You will continue to gain the perspective of people who have experienced mental health problems by reading two transcripts of a case study that give two views of how depression affected Kate.

Activity 4

In this excerpt taken from Lorraine and Kate: Depression (OpenLearn, 2016), you will read how Lorraine noticed how work was taking its toll on her friend Kate. You will then have the opportunity to read about Kate’s own perspective.

Note in the response box below any life stresses that had a harmful effect on Kate’s mental health.

Part 1: Lorraine’s story

I’ve been friends with Kate since we were at primary school. After school I went to work for an estate agent, got married and now have a toddler and am expecting again. I still work at the estate agents, part-time. Kate got a job working for someone in a big firm in Leeds.

She lived with her Mum and Dad and travelled daily at first. We saw each other most weeks, went for a drink at our local, to the cinema, that sort of thing. Then Kate moved into a small bed-sit in Leeds but she mostly came home at week-ends and we kept in touch.

When Hayley was born she thought she was cute and would drop in to see us. We got a routine of us going out for the evening every other week. Kate’s job seemed very pressured. She had to have her work mobile on all the time because the people she worked for were overseas a lot and they could ring her any time.

So she didn’t want to go to the cinema or to the leisure centre in case she missed a call. Our nights out became less regular and when we did go out they were less fun, she seemed to be edgy.

We went away for two week’s holiday and we hadn’t arranged another meeting. Kate said she would ring when she was free. Weeks went by and it was a relief when she did ring. She said she didn’t want to meet because she wasn’t well. She was ‘signed off’. When she told me it was depression I told her how glad I was it wasn’t something serious.

That was over a year ago. I know now that depression is serious and that I said the worst thing possible. But I didn’t know and I hope I’ve been a good friend all the same. Kate hasn’t gone back to the job in Leeds but she’s much better although her medicine is still not quite right for her. Sometimes when they try a change of pills she gets side-effects and feels awful but she’s the old Kate again.

Now read what Kate said about the stress she was under.

Part 2: Kate’s story

Looking back I don’t really know how this happened to me. I suppose I did work too hard and I hadn’t had a proper holiday. How could I afford one, the money I’m chucking at my landlord? The best I can do is going back to Mam’s.

I just reached a point where work overwhelmed me. The inbox seemed to just fill, and I’d work harder and harder, but more and more things to do would appear. I felt stressed and anxious the whole time.

There were just some days I could hardly get out of bed because I knew what was waiting for me when I got to the office. And I was so tired as well, constantly tired. I had been keen on running, but that went out the window – even if I’d had the time, I could barely lace my shoes never mind get round the park.

I was lucky; I was at home when I ‘broke down’. It was a Monday morning and I just couldn’t get out of bed. Mum came in to see what had happened and I just started to cry and cry and couldn’t stop.

I couldn’t even talk to her, I just cried. She was worried, so she got me straight down to the surgery and our GP was great. He took it seriously – which surprised me to be honest. Thank god for that.

It’s a year later, I still have regular check-ups because I’m not back to normal and the medication still isn’t right. There are days when I don’t want to see anyone and I find crowds dreadful.

When I meet people I have to work hard at concentrating on what they are saying. Friends think I’m OK but I’m abnormally tired after being with them. Apart from thinking depression wasn’t serious Lorraine has been great and I love just seeing her and Hayley.

Watching Hayley crawl around takes me out of myself. I can see that I still worry too much. I realise it is me, I wasn’t over-worked, I’d got things out of proportion. Yes, I can see what went wrong but I still don’t know why.

Comment

You have read about the same situation from two perspectives. First Lorraine tells us how she observed Kate change from the good friend she used to know to the more distant and ‘edgy’ Kate. Kate’s symptoms match many you have read about earlier: feeling overwhelmed, being stressed and anxious, constantly tired, staying in bed, crying a lot and isolating herself. These are all typical signs and symptoms of depression.

What life stresses did you note that affected Kate? She was, perhaps, overworked without adequate time to relax between work days, being pressured to perform for her employer, and she had money worries (the rental on her flat). It was all at a time when she moved away from her support network – Lorraine and her Mum.

In the next topic you will learn more about some of the interventions commonly used to alleviate mental health problems.

4 Mental health care and treatment

During the twentieth century, care and treatment of the mentally ill developed from an institutional system based in large mental hospitals to a largely community-based care system. The old mental hospitals provided custodial care, which required patients/inmates to live in a self-contained hospital community, supervised by a separate community of doctors, nurses and other service workers, such as an upholsterer, head gardener and cobbler. Today’s community care has most service users living independently, in small groups or with their own families, in the same community where the rest of us live.

Care and treatment has also evolved. The introduction of effective medication in the 1950s led to the gradual closure of the old hospitals and less need for constant supervision of individuals with serious mental health problems. Concurrently, new talking therapies were introduced that helped individuals to cope with life’s stresses. Today there is a range of effective medication that is used to treat mental health problems from schizophrenia to depression. Whereas at one time the goal was containment and alleviation of symptoms, today the goal of treatment is recovery.

4.1 Recovery

The concept of recovery acknowledges that the individual with mental health problems wants to have a meaningful and satisfying life, and it is the individual who defines for themselves what is meaningful and satisfying. With support from professionals, carers and fellow service users, the individual moves forward to attain their goals.

In their factsheet on recovery, Rethink, a major mental health charity and campaigning organisation, describes recovery as having components:

- working towards your goals

- having hope for the future

- something you achieve for yourself

- being an ongoing process

- taking responsibility for one’s life.

This, of course, depends on what is realistic for each individual.

4.2 Therapies

Today there is a wide range of medicines used specifically to treat mental illness, e.g. antipsychotics to treat schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, antidepressants for depression and anxiolytics to alleviate the symptoms of anxiety.

Talking therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) are now commonly prescribed, either as an alternative to medication or in conjunction with tablets. These recognise that the individual should be involved in their own recovery. They take the form of a programme guided by a therapist and which the person follows, doing ‘homework’ to practise what they learn. Examples are psychological help to overcome fears or other constraints to leading a full and active life.

Talking therapies are often used to treat irrational worries such as a fear of open spaces or heights. The therapist might think the appropriate treatment is a course to desensitise the person to being outside their house. In this psychological therapy the person would be exposed gradually to the situation that the phobia is about while carrying out a relaxation activity.

Activity 5

You will now match a treatment with specific mental health problems. Read the four scenarios below. When you have finished, select what you think is an appropriate treatment from the list.

a.

Antipsychotic medication

b.

CBT with antidepressant medication

c.

Counselling for PTSD

d.

Admission to a mental health unit

The correct answer is b.

Comment

As Ray has depression, the use of antidepressants at the same time as talking about his problems is probably the approach that would help him the most.

a.

Sectioning under the mental health law

b.

Desensitisation for a phobia of open spaces (agoraphobia)

c.

Antidepressant medication

d.

A leaflet on self-help

The correct answer is b.

Comment

It is most likely that Betty has a phobia, for which the appropriate treatment is desensitisation.

a.

CBT with antidepressant medication

b.

Sectioning under the mental health law

c.

Antipsychotic medication

d.

A paper bag

The correct answer is c.

Comment

It sounds like Carl has psychosis, which might develop into schizophrenia. Antipsychotic medication would help him at this stage of his mental health problems.

a.

Counselling for PTSD

b.

Sectioning under mental health law

c.

Antipsychotic medication

d.

Desensitisation to car crashes

The correct answer is a.

Comment

As Maya has PTSD the best approach is to offer her counselling, a type of talking therapy.

5 Carer experience

Mental health problems can have a huge impact on relatives and friends who support the cared-for person. They can be emotionally draining and upsetting, and many carers are not prepared for their new role. However, many carers also find a sense of achievement in their caring role and the relationship with the cared-for person becomes deeper and more meaningful.

Within this topic you will look at how caring for a family member impacts on family carers. You will examine family carers’ rights, and their relationship and engagement with mental health services. You will also consider how a more carer-centred approach might help to develop a relationship between family carers and mental health services.

5.1 Relationships and engagement

Caring for a relative with severe mental health problems is a distinct and unique experience and a steep learning curve for which few people are prepared. The relationship and engagement between families and professionals is therefore of great importance.

Activity 6

Reflect on how you think family carers should be helped by mental health professionals. Jot down your thoughts in the box below.

Comment

You might have considered that family caring in mental health is distinct from other kinds of caring and also very personal to the relationship the family has with the cared-for person. Because of this, you might think that mental health professionals should recognise that the needs of the family are not necessarily the same as the needs of the person being cared for. You might have thought that it is better if the family is involved and included in decisions made about the cared-for person and is acknowledged as a source of expert knowledge.

It is possible that you jotted down some barriers to effective caring: carers being taken for granted and isolated. Your own experience might have led you to conclude that family carers have been trapped in the confines of their caring role and just expected to cope.

On a more positive note, you perhaps know that there are ways to overcome these barriers, for example by taking into account family carers’ rights and responsibilities. This means listening to and taking seriously what they have to say. Providing timely support and assistance demonstrates to families that their responsibilities are recognised, and that they have a valued part to play in decision making and treatment approaches. It would also be to the family’s advantage to learn more about mental health and highlight any cultural diversity elements to professionals.

Key points from Section 2

In this section you have learned about:

- the terminology used to explain mental health problems

- particular types of mental health problems

- the effect mental health problems might have on the cared-for person

- specific examples of care and treatment

- the impact mental health problems might have on family carers.

Section 3 looks at palliative and end-of-life care. Studying Section 3 will show you how to maximise the cared-for-person’s quality of life, as well as how to support someone to reduce trauma during the final stages of life.

Further information (optional)

Now you have completed this section, why not explore OpenLearn for more on mental health? The BBC, in partnership with The Open University, broadcasts topics around mental health, such as All in the Mind. Why don’t you find out when you can listen to one of these programmes?

A large proportion of homeless people have diagnosable mental health problems. Think about what their lives must be like, and of ways in which you or others could help.

Using the internet, explore what charitable organisations and mental health campaigning groups offer. The sites for Rethink, MIND, the Alzheimer’s Society and Age UK offer a huge amount of information, resources and advice about mental health problems.

Section 2 quiz

Well done, you have now reached the end of Section 2 of Caring for adults, and it is time to attempt the assessment questions. This is designed to be a fun activity to help consolidate your learning.

There are only five questions, and if you get at least four correct answers you will be able to download your badge for the ‘Mental health awareness’ section (plus you get more than one try!).

- I would like to try the Section 2 quiz to get my badge.

If you are studying this course using one of the alternative formats, please note that you will need to go online to take this quiz.

I’ve finished this section. What next?

You can now choose to move on to Section 3, Palliative and end-of-life care , or to one of the other sections, so you can continue collecting your badges.

If you feel that you’ve now got what you need from the course and don’t wish to attempt the quiz or continue collecting your badges, please visit the Taking my learning further section. There you can reflect on what you have learned and find suggestions of further learning opportunities.

We would love to know what you thought of the course and how you plan to use what you have learned. Your feedback is anonymous and will help us to improve our offer

- Take our Open University end-of-course survey.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Frances Doran (Operations Training Supervisor at Leonard Cheshire Disability) and John Rowe (Lecturer for The Open University).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Images

Figure 1: © Marjan Apostolovic/iStockphoto.com

Figure 2: © Photogal/iStockphoto.com

Figure 3: © Andreas Solaro Stringer/Getty Images

Figure 4: © Chakrapong Worathat/Dreamstime.comExternal

Figure 5: © Tawheed Manzoor in Flickr https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by/ 3.0/

Figure 6: © Alina Solovyova/iStockphoto.com

Video

Activity 3: Transcript: (Stephen Fry) from Keeping Britain Alive, Episode 2 © BBC