Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 10:17 AM

Positive risk-taking

Introduction

Risk is a necessary and important part of life for all of us but we need to think about and manage this risk. In this section you will be looking at risk in relation to cared-for people. The cared-for person has the right to take risks. When managing risk, however, there is the potential for carers to be cautious with an emphasis on overprotecting the cared-for person. In this section you will be exploring how carers can continue to empower the person they are supporting to have a more fulfilling life – in particular through positive risk-taking.

Here we suggest that positive risk-taking can bring real benefits when it takes into account the needs and preferences of the cared-for person, the rights and responsibilities of their carers and the specific circumstances. The cared-for person is enabled to grow in confidence, learn from their experiences, develop new skills and abilities, or maintain the ones they already possess, and make full use of their opportunities and potential.

The course team acknowledges that there can be challenges with positive risk-taking. Paid care workers might feel more constrained than informal carers when it comes to positive risk-taking. Their employer might restrict what they would wish to do. At the same time, the informal carer might not be aware of the opportunities that could enhance the life of the cared-for person if they are encouraged to take positive risks.

You begin your study by looking at mental capacity. You then examine how independence can be encouraged and nurtured, followed by learning how carers can adopt the least restrictive practice (which means allowing the cared-for person to do the things they can still do) when considering risk to individuals. In the last topic you reflect on what happens when the cared-for person’s carer is unavailable and an emergency care plan is required.

At the end of the section there is a short quiz to test what you have learned about positive risk-taking. On successful completion of the quiz you will earn a digital badge.

This section is divided into four topics and each of these should take you around half an hour to study and complete. The topics are as follows:

- Mental capacity is explained and you learn about how capacity is assessed and the role carers might have in dealing with capacity.

- Promoting independence is about supporting people to reach their full potential and to be able to do as much as they can for themselves.

- Least restrictive practice is about ways to support people to enjoy independence and life-enhancing activities in the safest possible way.

- Emergency care plans are discussed in relation to why they are necessary and the type of essential information required.

Learning outcomes

By completing this section and the associated quiz, you will be able to:

understand why positive risk-taking is important as a means to enable cared-for people to have a more fulfilling life

understand how carers can balance positive risk-taking while providing safe care to the cared-for person.

1 Mental capacity

The law says you have to start from the position that everyone has the capacity to make decisions about their lives. Some people are born with limited capacity: through brain damage, for example. Other people lose their capacity to understand information and make decisions about themselves through accident, ill-health or a degenerative ageing process.

To better understand how capacity relates to the caring role, you first look at what capacity is and how it might affect a cared-for person. You go on to learn about how capacity is assessed and then how the caring role might be affected by the cared-for person’s capacity. Your learning from this topic will help you to appreciate how mental capacity and positive risk-taking are linked. For the cared-for person, having the mental capacity to make decisions is an important element in being able to judge exposure to risk.

Activity 1

Reflect on what you know about dementia or another serious health condition, such as a stroke, and make a list of the ways that the cared-for person’s mental capacity might be affected.

Comment

A feature of dementia is that the person gradually loses their ability over a period of time to remember and think clearly. Some health conditions such as cardiovascular accidents (strokes) can have the same effect. This of course can mean that a person’s ability to understand information and make decisions based on that information is impeded. Mental capacity might affect a cared-for person in a number of ways: for example, they are no longer able to manage their financial affairs, or decide on what to eat or which clothes to wear that are appropriate to the weather.

How capacity is determined is governed by law. The relevant law in Scotland is the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. At the time of writing, the Northern Ireland Assembly is considering a Mental Capacity Bill. In England and Wales the Mental Capacity Act 2005 is the primary legislation that sets out what capacity is and how an individual’s capacity is managed.

Crucially, the Mental Capacity Act states that a person lacks capacity if they are unable to make a decision for themselves in relation to a specific matter at a particular time. It acknowledges that the ability to make decisions can change with circumstances. For example, if a person lacks capacity to manage their financial affairs at one time, it should not be automatically assumed that they lack capacity to manage their financial affairs ever again.

A person’s capacity may be permanently affected due to dementia, a learning disability or brain injury. However, it is not associated with any particular condition and is dependent on an assessment being made before any decision about capacity is made. Capacity might also be temporary. An older person might become temporarily confused due to a urinary tract infection, for instance, but then receive treatment and recover and regain their ability to make informed decisions.

In the next part you learn more about the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and how it might protect the cared-for person.

1.1 The Mental Capacity Act 2005

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 details certain principles or guidance by which capacity should be assessed. It states how managing a cared-for person’s capacity must be carried out.

These principles are summarised below.

- Capacity must be assumed, unless a lack of capacity is established (i.e. the starting point is to assume someone is able to make decisions).

- A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them to do so have been taken without success.

- A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because they make an unwise decision.

- Any decisions or actions made related to capacity must be in the cared-for person’s best interests.

- Any decisions or actions taken related to capacity must be achieved in a way that is least restrictive of the person’s rights and freedom of action. (You learn more about least restrictive practice later in this section.)

Activity 2

To help you understand how the principles are applied, read the brief case study below. Would you conclude that the person at the centre of the case study, Desmond, has capacity or lacks capacity?

Case study: Desmond

While out shopping Desmond collected his pension and gave half to a Big Issue seller. He then found and wore a colourful hat, which he wore to the supermarket where he bought some processed food and enjoyed a strong coffee with four sugars.

Later that day a neighbour told Desmond’s daughter that he should not be allowed out by himself as he had made a fool of himself and clearly was unable to look after himself properly.

Comment

It seems that the neighbour who witnessed Desmond’s behaviour earlier that day assumed he was not able to look after himself as he should. You might argue about how wise Desmond’s decisions were, but they do not necessarily demonstrate lack of capacity to make decisions. At this stage, no attempt had been made to ascertain if Desmond was able to understand any concerns about his behaviour, retain information about any concerns, think through why his neighbour was concerned or communicate his own views on what he was doing.

Placing restrictions on Desmond’s trips to town would not necessarily be acting in his best interests as it would deprive him of the opportunity to act independently and stop him doing what he wanted. If his daughter and others continued to have concerns about Desmond’s behaviour they could ask for an assessment of his capacity.

You learn more about assessing capacity in the next activity.

Activity 3

1.2 Assessing mental capacity

When assessing someone’s mental capacity, in the first instance you should always presume a cared-for person has sufficient understanding or mental capacity to make decisions. Only when you have real doubt about the cared-for person’s capacity to make a decision in a particular situation should you make an assessment and a decision for them – for example, when the person is considering moving to a care home or when they start giving away their money. Before deciding someone lacks the capacity to understand information and make decisions, you should first establish if the person can be supported in making their own decisions.

Questions you could ask are:

- Does the person have any mental impairment?

- Are there any signs or symptoms of disability, illness or cognitive decline?

If yes, further questions are:

- Should these issues be assessed and treated before lack of capacity is determined?

- Does the impairment or disability prevent the person from making the decision? Being ill, disabled or mentally impaired does not automatically lead to a lack of mental capacity.

In many circumstances, such as everyday decisions, the carer might be the best person to answer these questions. However, for some decisions a person’s mental capacity needs to be assessed and this would be the responsibility of professionals such as a social worker or a doctor. In these circumstances, every effort to help the person to understand the information and to make a decision must be made before judging that the person can or cannot make their own decisions.

1.3 Mental capacity and decision making

If the cared-for person lacks capacity to make a decision, then someone else might have to make the decision on their behalf. Very often it is the carer who accepts this responsibility. However, there are times when the responsibility does not lie with the carer.

Some decisions about social care services that require funding or treatment for a health condition are normally made by a health or social care professional. However, although this type of decision is outside the responsibility of the carer, the carer should still be consulted and asked for advice as they will usually know the cared-for person best.

The law says that any decisions must be made in the ‘best interests’ of the cared-for person. This means taking all the relevant factors into account, including:

- consulting the carer and any other family members and close friends

- involving the cared-for person as much as possible and listening to what they say

- taking into account the cared-for person’s past opinions, values and beliefs

- restricting the person’s freedom as little as possible.

When the carer is asked to help, it is important that their opinions are taken into account. You can do this by listening to them and remembering that they often have a better understanding of the cared-for person than anyone else.

2 Promoting independence

To promote independence means to support a person to reach their full potential and really do as much as they can for themselves.

This topic will help you to recognise that the concept of independence varies from person to person and to appreciate the impact independence can have on everyday life.

A valued life is one where a person is given respect, dignity and privacy and is supported to make their own choices about what happens to them. This topic will help you to understand this, so you can support the people you care for with a better awareness of the role positive risk-taking can play in helping them in gaining or retaining their independence.

The Care Act, which came into force in England in April 2015, replaced most of the current law regarding carers and people being cared for, and put new obligations on local authorities. One of these is a general duty to promote an individual’s well-being. This means that they should always have people’s well-being in mind when they make decisions about them or plan services. The term ‘well-being’ includes:

- personal dignity (including treatment of the individual with respect)

- physical and mental health and emotional well-being

- protection from abuse and neglect

- control by the individual over day-to-day life (including over care and support)

- participation in work, education, training or recreation

- social and economic well-being

- domestic, family and personal relationships

- suitability of living accommodation

- the individual’s contribution to society.

Local authorities have to consider the impact of your role as a carer on your well-being. Similarly, they have to consider the impact of a disabled person’s needs on their well-being.

In a paper published by Scope, Our Support,Our Lives (Davies, 2015), about the right to independent living, we are told that social care is about more than just the basics and must enable disabled people to live fully independent lives, putting them at the centre of their own care. This concept applies to anyone receiving care, not just people with disabilities, and Scope says that this is the key to being able to achieve the well-being principles outlined in the Care Act.

Definition of well-being from the Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014:

- a.physical and mental health and emotional well-being

- b.protection from abuse and neglect

- c.education, training and recreation

- d.domestic, family and personal relationships.

Activity 4

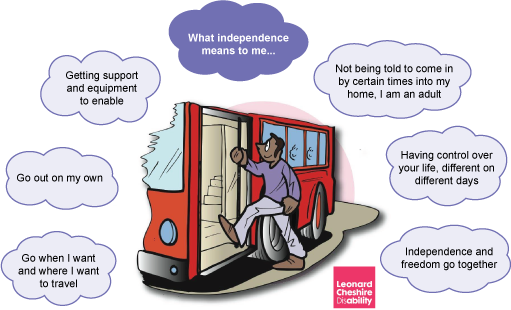

The quotes in Figure 1 are from a Customer Action Network meeting at Leonard Cheshire Disability when participants were asked what independence meant to them. These are things that most of us take completely for granted, but for people living with disabilities or other conditions that make them dependent on others, that is how they define independence.

Look at what someone with a significant disability can achieve with the right support. Ray De Grussa mastered using specialist computer software to achieve his ambition of composing music. He received an award at Adult Learners’ Week in 2012 but his real reward was that he was finally enabled to achieve his ambition.

2.1 Care or support – what’s the difference?

There’s a subtle but very important distinction between caring for someone and supporting them, which can mean the difference between being just ‘ok’ and living to their full potential.

Caring for someone

Although we use the term ‘caring for someone’ throughout this course, and it is the most widely used term for looking after someone, the simplest care involves helping someone in their daily needs. An example of simply caring for someone would be ‘Would you like a cup of tea?’ to which the reply is ‘Yes’. The carer then makes and hands the individual a cup of tea. On the face of it, this looks like good care but what part does the cared-for person play in this task?

Supporting someone

If ‘caring for someone’ is the minimum standard, ‘supporting someone’ goes to the next level. It is about empowering people to take more control over even the smallest things in their lives or even a small part of a small thing; things that most of us would take for granted. Basically, it’s about seeing every ‘care need’ as an opportunity to help the person you care for to make choices, develop skills and be more involved in creating their own outcomes. This should be a gradual process, bit by bit supporting the person to lead a more fulfilled life.

Let’s go back to our example of the cup of tea. You have asked ‘Would you like a cup of tea?’ and the reply was ‘Yes’. The extra step is supporting the individual to complete as many of the stages of making the tea for themselves that they are able to. They may only be able to put the tea bag in the cup but that is a start. Maybe they could also switch on the kettle and get the milk from the fridge in time. Yes, it will take longer but will be much more rewarding for the individual than just being given a cup of tea. It is true that it may be a nice thing to make someone a cup of tea but not if they never have the opportunity to make one for you.

Why the distinction is important

Without supporting the people we care for to become empowered there are few chances for them to continuously develop in all aspects of their life. By supporting them in even the smallest tasks, they make progress every day – it might be two steps forward, one step back, or only happen over a long period of time, but the important thing is they are making progress.

In terms of care provision it is important because it is the ‘harder’ path to take for staff and caregivers. It involves more patience, more thought, more involvement and more time. But becoming more involved in someone’s development engages carers more, and it is rewarding to see the person you care for achieve something new or be able to do something they were able to do when less care was needed. It gives better outcomes for both staff and carers and the people they are supporting.

As carers we tend to do things for the people we support as we underestimate their abilities or because it is quicker. But do you want to make life too easy for the people you support, with too many ‘get outs’? Why would they make the effort if you do it all?

This approach can lead to you telling the people you support what should happen rather than giving them the choice. Isn’t this the way that we treat our children until they start creating and living their own lives? And those who can’t communicate in the same way can become trapped and will often find another way to rebel in their desire for individuality. This can express itself as challenging or anti-social behaviour.

Activity 5

Read the case study below and put yourself in Betty’s shoes. Then answer the questions that follow.

Case study: Betty

Betty is a widow in her 70s who lived independently until she had a stroke recently. She has made a good recovery of her speech and cognitive skills but has lost the use of her right arm and is unsteady on her legs. Betty has family but none of them live close by and she receives support from a private home care service.

Betty gets frustrated at not being able to do all the things she used to, and feels the carer doesn’t have time to listen to her and find out what she needs: ‘She just carries out her tasks and goes off to the next customer.’

- How would you feel if you were Betty?

- How could the carer enable Betty to be more independent and do the things she wants in life?

Comment

Betty has already said that she thinks the carer doesn’t have time to listen so she may feel that she is being ‘a nuisance’. But other feelings may include frustration at having to be reliant on other people – she may be angry that this has happened to her. Betty has always been independent, so she may also be angry at herself because she can’t do everything she used to do.

The carer could take some time to find out about Betty’s feelings and the way she would like to be supported. They could work on a care plan so that anyone supporting Betty would know how she would like to be treated, and what is important to her and for her to enable her to have a good day.

By allowing Betty to do the parts of tasks she can manage for herself, she would feel more independent and less reliant on others.

2.2 People or technology?

Some disability charities, such as Sue Ryder, offer ‘re-ablement’ programmes that aim to help people who live with degenerative conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, or who have had strokes. Programmes such as this offer practical help and assistance to meet the specific needs of each participant.

Organisations like Reablement UK also offer training and support to care staff, giving them the knowledge and skills to work with people to regain their self-care skills and become as independent as possible.

Definitions of assistive technology

There is confusion and misunderstanding of the term ‘assistive technology’ at all levels – and this is not surprising. The technology is developing so fast that even the health professionals responsible for prescribing assistive technology will openly admit they are unaware of what is currently on the market.

However, there have been attempts to try to define assistive technology and what it can do. Here are two: the first is taken from the sales literature of RSLSteeper, a company that provides assistive technology equipment:

Assistive Technology is any device that helps a less able person do something that more able people can already do.

The second definition is from a user group consultation at the King’s Fund in 2001:

Assistive Technology (AT) is any product or service designed to enable independence for disabled and older people.

Although these definitions are accurate, they don’t really help to explain the vast array of technology out there, the different purposes of it or what it needs to be able to work effectively.

What we do know is that assistive technology can have a huge positive impact on someone’s life, as you will see from the following case study.

Case study: Beverley Glover

Beverley Glover is a great fan of assistive technology. She uses her device to open her doors, windows, curtains, raise and lower her bed, control her TV, DVD and fan, make calls to her daughters and, at Christmas, uses her lamp control to switch on her Christmas tree lights!

She also uses a communication device when she is out and about, which helps people to understand her.

Bev bought her equipment independently, but she was assessed by a specialist regional service in the north west who now provide her equipment,maintain it for her and add on bits of electrical equipment when she needs it – all for free.

Types of assistive technology

Assistive technology can be categorised in three ways:

- Augmentative or alternative communication

This refers to processes and tools to aid one-to-one communication, for example everything from communications passbooks (explaining a person’s background and preferences) through to a ‘grid’ (a Perspex board with words bordering a clear space so the recipient can see which word the user is looking at) to electronic devices that speak for the person (Primo).

- Communication assistive technology

For people with impaired speech, such as those living with conditions like cerebral palsy, autism or strokes, speech generation devices can help to enhance their existing capabilities or give a voice where speech is severely impaired.

- Environmental assistive technology

These technologies assist a person to engage with their living space, and can open and close doors and windows, curtains and blinds. It can turn lights on and off, and control heating as well as home entertainment. The technology can also answer and make phone calls, activate alarm or nurse calls, and control the functions of a bed.

How does assistive technology work?

As long as a piece of equipment has either an infrared or a radio signal in an independent living environment, the device can be used by someone with disability. Simply controlled devices such as table lamps can be converted by an adapted plug, which is then controlled by an infrared signal.

In the case of doors, windows, curtains, blinds and light fittings, the most satisfactory way of incorporating the technology is during the building of a property.

Devices can be fitted retrospectively, and while the additional wiring on the walls may not look very attractive, it is better to have the technology than not.

Note: Environmental technology that affects the building will not be funded by NHS assistive technology providers. In the case of supported living, however, depending on location, Social Services may assess the living environment and make adaptations to suit the needs of the patient.

Gaining access to equipment is achieved through a control device in the same way that an able-bodied person would turn on the TV with a remote control. What access is easiest for the individual will determine the type of control device and switch prescribed. When people say that assistive technology doesn’t work for them, access will usually be the problem. For example, the door or window will open and close remotely but the means to open it for that person has not been assessed correctly and is causing problems.

There are many, many controls and switches on the market and consequently choice can be daunting. People choosing assistive devices will need to take into account their condition and whether it is likely to deteriorate, to ensure the chosen device is the most appropriate one for them.

The next activity will start you thinking about the benefits of assistive technology.

Activity 6

Read the case study below and then answer the question that follows.

Case study: Ray Grocott and his Freeway machine

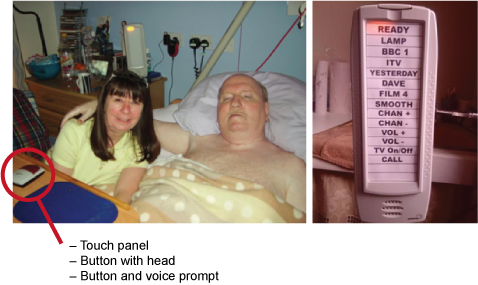

Ray Grocott lives in a Leonard Cheshire Disability residential service. Figure 5 shows Ray and his wife Diane, and Ray’s Freeway machine. Ray uses a Freeway device, which allows him to, for example, turn on lights, lamp, TV and radio, and to open doors and windows that are connected to his Freeway. As he is unable to hold the device, he can use a switch that can be activated by whatever movement the individual is capable of, such as head, chin, finger, foot and so on.

Diane realised the power of the technology when she was on the phone to Ray one evening. She told him, ‘There’s a great programme on BBC1.’ But as she began to explain it to Ray she was interrupted by a voice in the background, ‘Are you ready, Ray…, Lamp…, BBC1’ and they were able to watch the programme together.

Diane travels a lot for work and listens to audio books. She now shares her audio books with Ray who can access them when he wants. This has given them new topics for conversation.

Ray goes home at the weekends. North West Assistive Technology, their NHS assistive technology provider, has duplicated Ray’s system in his own home. When he wakes in the night he can turn on his light and the TV without breaking Diane’s sleep, which makes life so much better for Diane.

Diane said: ‘The Possum Freeway 2 has changed Ray’s life. To lose it now would be like him losing another ability.’

And Val Kirk, Assistant Therapist at Hill House (the Leonard Cheshire Disability care home) said: ‘Being empowered to take back independence which has been robbed from individuals by debilitating illness has improved their whole well-being.’

How do you think assistive technology has benefited Ray and his wife?

Comment

You may have thought about the following:

- The technology has increased Ray’s independence, giving him more control over his life.

- It has enhanced Ray and Diane’s relationship as it enables them to share activities and gives them more to talk about.

- As the technology has been duplicated in his home, Ray can be independent at home and this in turn enhances Diane’s life by giving her a better night’s sleep.

3 Least restrictive practice

What have you done today that could be considered risky? You might have driven a car, crossed a road, made a cup of tea, taken the dog for a walk …

Figure 6 Risky activities?

- Do you know what risks you are taking every day?

- If someone suddenly told you that you aren’t allowed to drive because of the risks involved, what would you say?

- If you never took a risk what would happen? Would you grow as a person?

- Do you think of risk as positive or negative?

Often risks are associated with injury, loss, danger, damage or threat, and if a risk is perceived negatively, it can be used as an excuse to prevent people from doing something.

For example, some people may think that direct payments and personal budgets could put people more at risk of abuse and exploitation; others may feel they reduce risk by giving people greater control over their lives.

Taking risks is an everyday part of life – and life without risks would be very dull indeed. While it is important to try to identify risks in advance and reduce the likelihood of them happening, this shouldn’t be an excuse for preventing people from having choice and control over their lives.

Do you like to have a drink in the pub or to go for a meal with friends? It’s an opportunity to socialise and catch up with people, which is important to us for all sorts of different reasons. But you may have also been told that you need to lose weight, or you need to cut down on the amount of alcohol consumed as you are drinking more than the recommended limits than is good for you. You can weigh that up and make a choice – do you go to the pub/restaurant or do you stay at home and eat a healthy meal?

If that choice was taken away from you, how would you feel?

There has to be a balance and you need to ensure that you do not prevent someone you care for from having the right to do something simply because you do not believe it is good for them. You need to empower people and help them to access opportunities and take chances – and be positive about potential risks.

If you try to prevent people from doing anything that could be regarded as dangerous, you could potentially be preventing somebody from doing something they have the right to do.

Sometimes it can be difficult for carers to know where the boundaries lie in terms of what they can/can’t or should/shouldn’t do. In the next activity you will look at an example, and write down what you think your responsibilities would be in relation to your care of Sheila.

Activity 7

3.1 Deprivation of liberty and restrictions

To start you thinking more widely about this topic and what it means for carers, take a look at this video about Tim and his desire for fish and chips.

Transcript: Working in an empowering way – fish and chips

Working in an empowering way – fish and chips

The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) are part of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. They aim to make sure that cared-for people are looked after in a way that does not restrict their freedom more than necessary. The safeguards should ensure that this is only done when it is in the best interests of the person and there is no other way to look after them.

A recent court decision has provided a definition of what is meant by the term ‘deprivation of liberty’. A deprivation of liberty occurs when ‘the person is under continuous supervision and control and is not free to leave, and the person lacks capacity to consent to these arrangements’.

Any type of restriction applied within a care setting (including the person’s home) must be risk assessed and consent gained for the specific act. If someone doesn’t have capacity, and arrangements are made on their behalf, the ‘least restrictive option’ should always be chosen, especially if the restrictions used mean that carers have ‘complete and effective control’ as this could constitute a deprivation of the person’s liberty.

Activity 8

Read this article from the Daily Mail (2012), which gives an example of how the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards were used to ‘overprotect’ somebody.

Comment

Although the person in question had dementia, it could not be proved that she was unable to make a decision about going on holiday.

The couple had been on many cruises in the last 20 years, so she would have an understanding of what the decision was about.

The council had been more concerned with finding ways to prevent her going on a cruise than with finding ways to make it possible.

3.2 The search for the least restrictive option

When professionals talk about using the ‘least restrictive option’ for cared-for people, some people think this means letting the person do whatever they want, even if it puts them at risk. The use of the least restrictive option applies only if the people you are caring for are considered to lack capacity under the Mental Capacity Act and should be used only if there is no better way to carry out the task. All people providing care should be comfortable with assessing capacity, but remember that just because someone makes a decision that others think is unwise, it doesn’t mean that they lack capacity – we all sometimes do unwise things even when we have capacity!

Capacity is what’s called ‘decision-specific and time-specific’: can the person make this decision at the time it needs to be made? The law says that we must do everything possible to enhance an individual’s ability to make their own decisions.

Activity 9

Read about Johnny and then decide in which areas of his life he needs support with decision making.

Case study: Johnny

Johnny lives in a residential home.

- He likes to wear his Manchester United kit when the team is playing.

- Johnny’s family have warned his support workers that when he is particularly anxious, he will try to go to major roads to look at lorries: he has been brought back from the motorway hard shoulder on several occasions.

- Johnny gets worried and anxious when he needs to go to the doctor or nurse.

- If he gets anxious Johnny can’t listen properly, which makes it hard for him to make decisions.

How can Johnny be supported? Write your thoughts in the space below.

Comment

People who care for Johnny could look for ways to improve his ability to make some decisions. They could perhaps ask his family for some tips on how to do this.

They could also find out more about what makes Johnny anxious, and particularly too anxious to listen properly. It will probably help to give him as much time as possible to make big or anxiety-producing decisions, and to repeat information in different ways, for example, by using pictures.

For little decisions, such as wearing his football strip, there is no reason to think that Johnny lacks capacity: he wears it when his team is playing. Even if he didn’t have capacity, there is no risk associated with this choice, so it should be respected and praised: it’s good to make choices and he is doing so.

Staff who support Johnny need to assess his capacity to understand the risk of going near major, busy roads. Maybe he cannot, for example, remember that the traffic goes really fast and may come on to the hard shoulder, or maybe he can remember this information but Johnny can’t use it to decide not to go to the motorway.

If the staff decide he lacks capacity to make this decision safely, then they must make a decision in Johnny’s best interests about how to plan for when he might want to go and look at lorries or show how he could look at lorries in a safer way than standing on the hard shoulder.

Johnny’s interest in looking at lorries has a lot more risk attached than whether he should wear his football shirt, and it would be completely wrong to say, ‘It’s Johnny’s choice to go and wander along the motorway so we must let him go.’

But we must not restrict his freedom more than is absolutely necessary. It would be far too restrictive, and not proportionate to the risk of harm, to lock Johnny in the house and deny him access to the outdoors because there is a risk that sometimes he will run after lorries.

Everything you do that might restrict a person’s freedom of action must be the least restrictive option that will meet the need – it’s not just about letting a vulnerable person do whatever they want, it is about keeping them safe while restricting their rights and freedoms as little as is possible.

Activity 10

What do you think might be the least restrictive option for Johnny, and how could you make the right decision in his best interests?

Comment

The best option, if it’s possible, might be to ask Johnny when he’s calm what he would like staff to do when he gets anxious. You could also consult his family to find out more about what might trigger this anxiety, and how best to respond.

Perhaps Johnny’s care plan could have regular ‘look at lorries safely’ time built into his walks with carers; he could have a scrapbook of lorries, or collect model ones.

The search for the least restrictive way to meet a need can uncover amazing creativity, and can involve the cared-for person and everyone involved in their care. The delight in finding an imaginative solution that keeps a person safe while respecting their rights is one of the real joys of providing adult social care.

4 Emergency care plans

So far in this topic you have learned about positive risk-taking that takes into account the cared-for person’s mental capacity, and ways to promote their independence using the least restrictive practice. Now you consider what happens when a carer is unable to continue in their caring role for whatever reason. Depending on the circumstances this might be for an hour or for weeks. In this topic you learn how an emergency care plan can contribute to positive risk-taking and you practise completing such a plan.

4.1 Why is an emergency care plan necessary?

Emergency care plans acknowledge the expertise and dedication of carers, and their responsibility in ensuring that as much as possible is done to make sure that the cared-for person continues to receive the care they need. The plans can be made either by the cared-for person or by their carers. However, whoever designs the emergency care plan, it is likely to consist of several similar elements.

Consider for a moment the wide range of activities performed by carers at every minute of every day. Depending on the situation, carers wash the cared-for person, dress them, administer their medication, help them use the toilet and clean themselves, take them shopping and advocate on the cared-for person’s behalf. These are just a small sample of roles and responsibilities that carers fulfil. When the carer is not available, the emergency care plan is one way that the cared-for person’s needs and preferences can be communicated to others.

It is important at this stage to point out that a situation where an emergency care plan is enacted is not a situation in which the cared-for person is subjected to additional restrictions. It is necessary to ensure that risk is managed in the best interests of the cared-for person, and that any risk management plan is implemented considering the potential positive benefits to that person. So, for example, if the normal carer is not available and less experienced carers take their place, it does not necessarily mean that any activities that the cared-for person normally does for themselves should not continue.

An emergency care plan is not just a document, it is a process. The process should involve preliminary discussions with the cared-for person, their family and carers. The discussions would attempt to foresee any potential emergencies for which the care plan is necessary and plan for them. This might need more than one conversation. At this stage the mental capacity of the cared-for person is discussed and an assessment arranged if it is thought necessary. (Mental capacity is discussed in Topic 1 of this section.)

4.2 Drawing up an emergency care plan

Drawing up a good and effective emergency care plan depends on accurate information being known about the cared-for person, and that this information is communicated in a way that others can understand. The next activity helps you to practise communicating information about a cared-for person succinctly and accurately, so that if another carer or professional needs to take action they can rely on the information in the plan to guide what they do.

You can carry out the activity as a carer for a specific person or, if you are not a carer, imagine someone you could be planning for.

Activity 11

Describe briefly the cared-for person’s diagnosis and their understanding of it. For example, ‘the person has dementia and they do not understand that they are not able to go out of the house unaccompanied’.

- What regular medication does the person take?

- What as required (or PRN) medication does the person take?

- Is there any medication for emergency use and, if so, where is it kept?

- Is there any care the person does not wish? (An example might be not to resuscitate.)

Comment

It’s quite difficult being brief when asked to summarise an individual’s personality, their needs, preferences and everyday life. However, it should be remembered that this is for an emergency care plan in which small bits of accurate information can be communicated better than larger amounts of information that is not so useful in an emergency situation.

The simplest way to list medication is to copy out instructions provided by the pharmacist or doctor’s prescription. This might also be on the box of tablets or bottle of medicine if available. Make sure it is up to date though.

Few people like making life and death choices for a relative but sometimes, such as in end-of-life care, treatments that are available might not be in the best interests of the cared-for person. In other situations, the cared-for person, with mental health problems, for example, might prefer not to be taken to hospital in an ambulance.

It is worth thinking about what actions are possible and the potential outcomes and consequences. This might need discussion with professionals as well.

Activity 11 was an initial preparation, which provided essential background information about the cared-for person that can be quickly understood in an emergency. Once an emergency care plan is finalised it should be shared with those likely to be called upon, including relatives, neighbours and professionals. Anyone it is shared with should have been consulted.

Now we would like you to think about what to do if an emergency occurs in the cared-for person’s home. Some emergencies are foreseeable and can be prepared for. Examples of foreseeable emergencies include:

- a person with dementia leaving the cooker hob gas on

- a person with dementia getting lost

- a young adult with learning disabilities having an epileptic seizure

- an individual forgetting to take their medication for diabetes.

Other emergencies, of course, are unexpected but plans for them can still be made. In the next activity you consider foreseeable emergencies for a cared-for person (or an imaginary one if appropriate).

Activity 12

Key points from Section 4

In this section you have learned:

- what mental capacity is and how it is assessed

- the link between mental capacity and positive risk-taking

- the different ways in which carers can offer support and encouragement to promote independent living and how assistive technology can help some people

- why considering least restrictive practice is important in acknowledging risk but balancing that against empowering and supporting the people you care for to do some things for themselves

- why an emergency care plan might be necessary

- common features of an emergency care plan.

As you are now aware, caring for someone can feel all-consuming, so it is important that carers also take the time to look after themselves. Section 5 offers some suggestions of how carers can look after their own well-being.

Further information (optional)

If you are interested in learning more about making decisions on behalf of a cared-for person that are in line with their best interests, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice provides a helpful overview – see Chapter 5.

Section 4 quiz

Well done, you have now reached the end of Section 4 of Caring for adults, and it is time to attempt the assessment questions. This is designed to be a fun activity to help consolidate your learning.

There are only five questions, and if you get at least four correct answers you will be able to download your badge for the ‘Positive risk-taking’ section (plus you get more than one try!).

- I would like to try the Section 4 quiz to get my badge.

If you are studying this course using one of the alternative formats, please note that you will need to go online to take this quiz.

I’ve finished this section. What next?

You can now choose to move on to Section 5, Looking after yourself, or to one of the other sections, so you can continue collecting your badges.

If you feel that you’ve now got what you need from the course and don’t wish to attempt the quiz or continue collecting your badges, please visit the Taking my learning further section. There you can reflect on what you have learned and find suggestions of further learning opportunities..

We would love to know what you thought of the course and how you plan to use what you have learned. Your feedback is anonymous and will help us to improve our offer.

- Take our Open University end-of-course survey.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Frances Doran (Operations Training Supervisor at Leonard Cheshire Disability) and John Rowe (Lecturer for The Open University).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Images

Figure 1: courtesy © Leonard Cheshire Disability, https://www.leonardcheshire.org/

Figure 2: © fotocelia/iStockphoto.com

Figure 3: © Eva Katalin Kondoros/iStockphoto.com

Figure 4: courtesy © Leonard Cheshire Disability, https://www.leonardcheshire.org/

Figure 5: courtesy © Leonard Cheshire Disability, https://www.leonardcheshire.org/

Figure 6:

(a) © MACIEJ NOSKOWSKI/iStockphoto.com

(b) © Osamy Torres Martin/iStockphoto.com

(c) © Mapodile/iStockphoto.com

(d) © Johannes Campaan/iStockphoto.com

Video

Section 3.1 Video and transcript: courtesy © Leonard Cheshire Disability, https://www.leonardcheshire.org/