Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 19 February 2026, 8:57 PM

Defining and exploring the voluntary sector

1. Defining and exploring the voluntary sector

Introduction

In this section you will be introduced to the voluntary sector and will consider what is unique to voluntary organisations and to charities specifically: what defines them. You will explore the context in which voluntary organisations work, some history of the sector and what brings all different kinds of voluntary organisations together.

Section 1 is divided into three topics:

Structure and regulation in the voluntary sector looks at where voluntary organisations have come from, how a typical voluntary organisation might be organised and what rules they have to follow.

Size, scope and role of the voluntary sector steps back to give an overview of the sector as a whole: what kinds of voluntary organisations are out there, what they do and who works in them.

Values-based organisations explores the guiding principles that underpin the voluntary sector and encourages you to consider them against your own values.

If you are already active in a voluntary organisation then it will help you to keep that organisation in mind throughout this section and think about how the organisation compares to others in the voluntary sector. If you do not yet work in the sector then this will help you to think about the kind of organisation you might be interested in being involved with.

Learning outcomes

By completing this section and the associated quiz, you will:

understand where some voluntary organisations have come from, and who they might register with and report to, if required

know more about the type and number of voluntary organisations in the UK and their staff and volunteers

have an awareness of what drives voluntary organisations and of the environment that they are working in.

1.1 Structure and regulation in the voluntary sector

Different institutions in society can act for the good of the public. Traditionally, there are three sectors: the public sector, the private sector and the voluntary sector, and each of these three sectors has a role to play in social development.

The public sector includes organisations that provide basic public services such as armed forces, policing, roads, education and health. These services are provided through income from taxation and, in the UK, national insurance. The public sector spends by far the largest amount on social welfare activity.

The private sector includes organisations and individuals that provide goods and services and their primary aim is to make a profit; for example, shops, manufacturers, financial services, etc. Profits are distributed to owners and shareholders as well as reinvested. Many private sector organisations endeavour to act in a socially responsible way through providing good conditions of employment, being a good citizen in the local community and supporting a clean environment by not wasting resources.

The voluntary sector is different from the other two sectors because it is not-for-profit and is not government controlled like the public sector. Traditionally, it has occupied a third space and sits between the public and private sectors. The third space is one where needs have not been met because the private sector has not seen it as profitable to do so and the public sector has either neglected these needs or not been able to afford to address them.

However, boundaries between the sectors have become more blurred. Think of private sector organisations now running services that used to be provided by local authorities or hospitals (for example, cleaning or waste collection). As the public sector has developed and evolved, the interface with the voluntary sector and its relationship with voluntary organisations as providers of services has changed and continues to change dramatically.

Public sector libraries are often run by volunteers instead of paid staff. There are also more partnerships between the sectors – for example, a new NHS hospital built using private sector finance – or voluntary organisations working with local authorities to provide social housing or care for children with disabilities. Another growth area is social enterprises which, although they are businesses generating profits, also have social or environmental goals.

Most organisations in all three sectors are regulated or inspected in some way so that customers or clients are protected. Organisations such as the Financial Services Authority, Ofcom, and the National Audit Office are often in the news reporting on some aspect of public or private organisations’ work. The voluntary sector is also partially regulated: this is the case of organisations that are registered charities, however not all voluntary organisations are registered. Those that are registered are subject to the Charities Act 2011 (England and Wales), the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005, the Charities Act (Northern Ireland) 2008 and the Charities Act (Northern Ireland) 2013. Registration and regulation of charities is done by the Charity Commission in England and Wales, the Charity Commission in Northern Ireland, and in Scotland by the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR). Fundraising by charities is also subject to regulation and this is done by the Fundraising Regulator.

Public benefit

The various charities acts define a charity as a body or trust which:

is for a charitable purpose, and

is for the public benefit.

Public benefit relates to:

the charity’s purpose and what it was set up to achieve

how the charity's purpose is beneficial

how the trustees will carry out the charity's purpose for the public benefit.

Public benefit is the legal commitment of charities and what the Charity Commissions or OSCR regulate. It also gives organisations the focus to demonstrate the benefits they bring to the public and their various stakeholders (Charity Commission, 2013). Decisions about whether a particular charity (in England and Wales) meets the requirement of public benefit is made by the Charity Commission and in law. In Scotland a broad definition of public benefit is enshrined in law (Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005), and it is the role of the OSCR to decide whether the charity meets a charitable purpose and is for the public benefit.

Why do we have charities?

There are many documented histories of the voluntary sector, with similarities and differences between the fields of interest such as health, social policy, environment and education. In general, early initiatives came from faith-based organisations providing almshouses, schools and care of the sick. Even old-age pensions and unemployment insurance schemes were administered by voluntary organisations.

The government gradually became involved, helped or took over some of these services. The ethos of the early twentieth century was liberal, in that the government saw its role as working with voluntary organisations to provide vital welfare services (Thane, 2011).

The emergence and development of the welfare state in the 1940s meant that the government took over responsibility for providing what charities had previously been providing independently. A general consensus began to emerge as to the role of charities (and other voluntary organisations) within the welfare state:

A charity should not duplicate or replace what is the obligation of the state to provide. This would be a pointless duplication of effort, and a misuse of charitable funds.

A charity should seek to complement and supplement what the state provides, pioneering new approaches, enhancing existing services and generally building on the basic provision undertaken by government.

The purposes for which an organisation is established will reflect the interests and concerns of its founders. Many charities have very tightly defined charitable purposes reflecting the founders’ intentions, which restrict what can be done. It is an important function of those charged with the governance of charities to interpret the purposes of the charity in light of present-day circumstances, A charity can also amend its governing document if there is a clear power allowing this. Certain powers are available in the Charities Act and the Companies Act and many charities also have specific powers of amendment in their governing documents. Where the change which the trustees wish to make is not covered by these powers, trustees can apply to the commission via a process of a cy pres scheme, which means that (in England and Wales) they have to apply to the Charity Commission. Whatever the source of the power, there will almost certainly be conditions that must be met when using it. The most common condition it to identify additional purposes that are near the original purposes. A charity for pit ponies might become an animal sanctuary, a faggot society (for collecting wood to burn heretics) might use its money for evangelism and St Dunstan's (which was restricted to treating soldiers blinded on active service founded on a wave of public sympathy after the gassings in World War 1) extended its remit to the welfare of all former service men and women. On the other hand, charities for the relief of girls in moral danger, which were popular in Victorian times (reflecting concern at the molestation of women servants and their consequent pregnancies) still find an active role in rape crisis and women’s aid, which is an interpretation of their objectives in relation to present-day needs.

Activity 1

Select a voluntary organisation that you have heard of or are interested in and then write notes on the following questions (you may need to look at an organisation’s website or leaflets to find the information). If you are already volunteering or working for a voluntary organisation then you might want to choose that one as your focus.

When was the organisation set up and by whom?

What was its original purpose and has that changed? If so, how and why?

How does the organisation demonstrate its public benefit?

Discussion

Here is an example of a registered charity in Oxfordshire:

In 1979 Oxfordshire County Council set up a museum at Cogges, a thirteenth-century manor house and farmstead.

It was originally a farm museum but due to increasing costs and falling visitor numbers, it closed in 2009 and then reopened under a different arrangement. It is now run by Cogges Heritage Trust with a small paid staff team and many volunteers. It is on lease from the Council but has to be self-financing. Its role as a museum is now downplayed and instead it concentrates on events, education and as a wedding and filming venue. It also promotes local food and sustainability.

The organisation has a website and is active on social media publicising what it does. Its purpose is to be somewhere for the local community to visit and relax, and to educate children and adults about its history and food sustainability.

The structure of typical voluntary organisations

The voluntary sector has much in common with other sectors in terms of the legal requirements for business and employment, the nature of many of the tasks that need to be done and the organisational structures that support these activities. There are ways though in which the voluntary sector is unique and one of these relates to the ownership of the organisation.

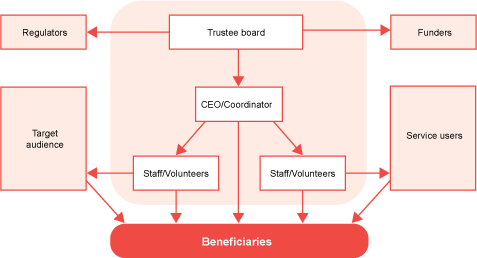

Figure 3 illustrates a typical charity structure, which includes a board of trustees who are responsible for the strategic direction of the charity and overseeing administration and management.

The CEO/coordinator/director will be the main point of contact between the board and the staff/volunteers.

Volunteers are a key element of voluntary organisations.

Beneficiaries are often the people being helped by the organisation.

The target audience might be members or beneficiaries, but could be different if the organisation seeks to influence government for example.

The regulators include the Charity Commission/OSCR/ CCNI, Companies House, HMRC.

The funders may include the people that you’re trying to influence (for example the government).

Some charities also have members, for example The National Trust.

You will now look at some of these in more detail.

The Board

Whilst shareholders or individuals may own companies, and the organisations may be in public ownership, voluntary sector organisations cannot be owned. Instead they have a board of trustees who act as custodians of the organisation and endeavour to cherish its values and ensure that it fulfils its mission. They have a form of accountability to the many stakeholders including funders, staff, volunteers and beneficiaries.

Boards in voluntary organisations can be called, amongst other things, management committees, executive committees or boards of trustees. If they are registered charities the roles and responsibilities of the trustees are defined in law and overseen by the Charity Commission or the OSCR.

In practice, boards of trustees are groups of people with different motives, backgrounds and skills. Effective boards provide leadership to any staff of the organisation, but do not carry out the tasks at an operational level. If the organisation is small and without any paid workers it is highly likely that the trustees will also be volunteers performing operational tasks. If this is the case it is important for them to be clear when they are acting as a trustee and when they are acting as volunteer workers.

Trustees usually carry out their trustee business by regular meetings, the frequency and timing of which is very dependent on the nature of the organisation. Sub-committees, special-interest groups and steering groups can be set up to run in parallel, involving trustees with special skills and other non-trustee volunteers. These must however report back and be accountable to the management board of trustees.

Trustees come from all walks of life and many voluntary sector organisations are endeavouring to create more diverse and representative boards that reflect their beneficiaries and other stakeholders.

The role of staff

Voluntary sector organisations employ people in a wide range of roles. Professionals such as accountants, marketing and communication specialists, administrators, IT technicians and HR professionals can all be found in the voluntary sector. They are employed because of their specialist professional skills which the organisation needs to deliver its services, raise funds and develop new projects. Frontline staff may include social workers, youth workers, vets, water engineers and counsellors.

Sometimes professional knowledge of other sectors is needed in order to shape a service. Those previously working elsewhere in relevant sectors can bring essential knowledge and understanding such as the nursing profession, education, the arts or the caring professions.

Many voluntary sector organisations are complex and need the same skills that might be needed in other significant organisations, or an even wider range of skills. In most small voluntary organisations staff will be expected to work across a range of areas (for example one person will carry out project work with some HR and IT duties).

While it’s true that many move in and out the voluntary sector, others develop careers totally within it, either by using their experience to support the activities of the organisation (such as a fundraiser raising money from charitable trusts) or developing skills related to the service user (such as a care worker in a residential care charity).

As the voluntary sector has evolved – bringing exciting opportunities, more complex funding streams and higher levels of accountability – the importance of having skilled fundraisers has increased, as well as skilled planners and managers, skilled ICT and HR professionals and of course qualified accountants to control the money.

Working in a smaller and a larger charity can be quite different. Larger charities tend to be more professionalised and corporate, but they also tend to have higher salaries and more professional development opportunities and possibly more job security. On the other hand, you might be able to see the difference you are making more readily in a smaller charity. However, the working environment might be less than ideal: perhaps several organisations sharing a small office, older equipment and fewer facilities.

One of the characteristics of many voluntary organisations is a relatively flat career structure with little or no formalised career path. It is often down to the individual’s determination and initiative to create their own pathway. Generally speaking if you have a general professional qualification and role – such as finance, marketing, HR or service delivery such as nursing or social work – there is more likely to be a structure through which you can progress, in larger organisations at least. In smaller organisations and in sector-specific roles such as fundraising, campaigning or volunteer management there may be less headroom and people may need to move to another non-profit organisation to find their next job.

The role of volunteers

Volunteers are essential to many voluntary sector organisations and their activities. Volunteers fulfil a huge variety of functions for no financial reward.

Individuals get involved with organisations on a voluntary basis for a huge range of motives, including the desire to make a difference, broaden social horizons, develop new skills and support a cause they passionately believe in. As well as donating money or equipment, many employers encourage their staff to work with voluntary organisations to share their expertise – thereby transferring knowledge to the organisation – or as regular volunteers. Young people are encouraged to undertake voluntary work as part of their own educational development and broadening of life skills.

It is important to recognise the influence that volunteers have within a charitable organisation and the need to listen to their views and seek feedback. Volunteers are often at the 'coal face', dealing directly with beneficiaries and delivering the organisation's services, so are well positioned to offer valuable insight to the organisation’s purpose and functioning.

The interface between trustees, staff and volunteers

The relationships between the key groups involved in the management of an organisation are crucial to the ongoing effectiveness of the organisation. In particular it is important that there is good and open communication between the groups, and clear and mutual understanding of their separate roles and responsibilities. The links between the senior management team (staff) and the (usually) volunteer trustees to whom they report are crucial and often where difficulties arise.

Likewise the relationship between paid staff and unpaid volunteers is sensitive. Some organisations are highly effective in harnessing the talents and contributions of volunteers at all levels and integrate them successfully into the overall organisation. Many charities (the smaller-income ones) have no paid staff and operate entirely with the efforts of volunteers. Others hardly use volunteers at all to deliver their services, or only for the most mundane tasks, and undervalue them. At the other extreme it is sometimes argued that some charities are guilty of exploiting them, expecting volunteers to take on tasks which could and should be paid work.

1.2 Size, scope and role of the voluntary sector

It is helpful to take a step back and consider the voluntary sector as a whole to get a picture of the context, scale and scope of people working together to make a difference. If you are already part of the voluntary sector this can be useful to you, helping you view your work or organisation alongside others within the sector to make comparisons and spot emerging trends. If you are looking to get involved with a voluntary organisation, then examining the sector as a whole gives you an idea of what is out there.

The voluntary sector today is made up of an increasing variety of groups and organisations ranging in scale, organisational structure, culture, size of membership and mission. Some are large national charities with well known names and logos, others are tiny local action groups. They may operate at an international, national or local level – or perhaps at all three.

The voluntary sector is actually very hard to define. Registered charities are part of the voluntary sector, but the sector also includes all organisations run by voluntary effort but which are not necessarily registered as charities, for example sports clubs and community groups. It also includes a growing number of socially focused businesses as well as political parties and housing associations, for example. This difficulty in defining the sector is reflected in the range of terms that are used to refer to the sector, many of which overlap. The most commonly used ones are:

the charity sector: this is a widely recognised term but organisations must meet the strict conditions required for charity registration. Not all voluntary organisations are charities.

the third sector: this term refers to the sector in relation to the private and public sector. The assertion that it comes third to those sectors is often contested, so this term is no longer widely used. (Note that this term is still used in Scotland.)

the not-for-profit/non-profit sector: this is another widely recognised term, but it can lead to a misunderstanding when charities do make a surplus, or ‘profit’, on certain activities. This surplus is allowed if it is then applied towards the charitable mission in other ways. The term also excludes socially focused businesses, such as social enterprises. To avoid this misunderstanding or exclusion, the term ‘beyond-profit sector’ is sometimes used.

the non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector: this term is more commonly applied to international organisations and particularly those with a campaigning focus, hence the emphasis that they are not part of government.

civil society: this is the widest term and refers to people working together to make a difference to their lives or the lives of others. As it isn’t a commonly known term outside of the sector, it can be confusing to some. In 2010 the government changed its Office of the Third Sector to the Office for Civil Society.

the voluntary and community sector (voluntary sector): this is an inclusive term for charities and organisations or community groups not registered as charities which undertake work of benefit to society. The ‘voluntary’ part of the term refers to the fact that all of these organisations are voluntary in some way: they have a voluntary trustee board, or money and/or time is volunteered. It is the preferred term among much of the sector and the one that will be used throughout this course.

Size and income of the voluntary sector

The National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO), as the largest umbrella body for the voluntary sector in England, annually publishes research on the sector in the UK Civil Society Almanac (the Almanac). The Almanac is produced by bringing together data from registered charities’ accounts, administrative data and surveys such as the Labour Force survey.

The largest body for the voluntary sector in Wales is The Wales Council for Voluntary Action (WCVA).

In Northern Ireland you have the Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action (NICVA), while the Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (SCVO) is the largest voluntary sector body in Scotland.

This short animation takes you through the key facts and figures on the voluntary sector from the Almanac 2018. Some of the figures will then be explained in more detail in the rest of this topic.

One way to consider the size of the voluntary sector is to look at the number of registered organisations. Because many voluntary organisations are not registered – either they are too small to register or they prefer to be a company or other structure where we cannot distinguish their social purpose – the Almanac reports the number of organisations as those that are currently registered as general charities (those registered charities that meet the criteria of formality, independence, non-profit distributing, self-governance, voluntarism and public benefit). This is:

However, if we consider the wider ‘civil society’ definition of people working together to make a difference to their lives or the lives of others, then it is estimated that there are around 900,000 groups working in this way. These blurring boundaries and definitions make it tricky to conduct research on the full voluntary sector. Therefore, this group of 166,001 registered charities is used for all of the Almanac analysis but we must bear in mind that the full sector is much larger.

Another way to consider the size of the voluntary sector is by its income and expenditure. Figure 5 below from the Almanac gives the overall picture of the money into and out of the voluntary sector in 2015/16.

From this figure we can see that in 2015/16 the voluntary sector got £47.8 billion pounds, a rise on the previous year, driven by the increase in income from individuals. Donations or purchase of products and services by individuals is the largest source of money for the sector. This is followed by government sources, although cuts to total government spending in recent years have followed through to the voluntary sector, which has seen a downward trend in government funding since a 2008/09 peak. Levels of government grants to the sector – £2.8bn – are less than half the level they were ten years ago.

In terms of spending, the diagram shows that 85% of the sector’s income in 2013/14 went directly to achieving its charitable aims. In order to maximise the amount of money available for their charitable activities, charities also need to spend money in order to generate further funds. Voluntary organisations spent £5.4bn on generating funds in 2013/14 and for every £1 spent, £4.20 was generated in return. More than nine in ten charities also hold some form of assets – such as buildings, cash, investments – which they use to contribute towards their charitable activities or to help generate funds.

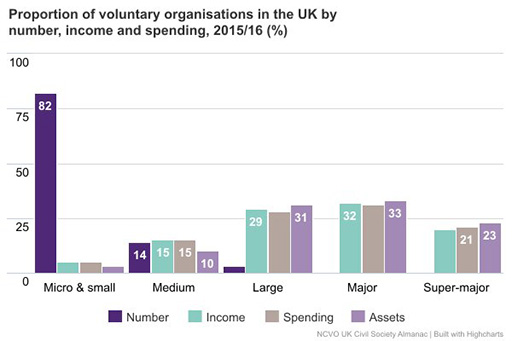

Money is not evenly distributed around the sector, which is very diverse. When a lot of people think of charities or the voluntary sector, they think of the large organisations like Oxfam or Cancer Research UK. Although these large organisations have a big proportion of the sector’s income, they are actually very few in number. In reality, there are considerably more small organisations in the voluntary sector than large ones.

Activity 2

Study the graph below that groups voluntary organisations by size (from micro to super major, as defined underneath) and shows how many organisations are in each group, along with their income, spending and assets. In particular, look at the first and second bars and try to extract the following pieces of information.

What percentage of voluntary organisations have an income of less than £100,000 per year, so are ‘micro’ or ‘small’?

What percentage of the sector’s income do the 3% of charities that qualify as ‘large’, ‘major’ or ‘super major’ receive?

Which size of organisation receives a total income that is roughly in proportion with the number of organisations in that category?

‘Micro’ is defined as less than £10,000 income per year

‘Small’ covers £10,000–£100,000 income per year

‘Medium’ is £100,000–£1million income per year

‘Large’ is £1million–£10million income per year

‘Major’ is £10million–£100 million income per year

‘Super major’ is over £100 million income per year.

Discussion

83% of all voluntary organisations have an annual income of less than £100,000, so are defined as ‘micro’ or ‘small’ organisations. These are likely to be local or specialist groups without any paid staff – sports or activity clubs, parent groups, rare illness support networks, for example. Even though they make up so much of the sector in number, they account for less than 5% of the total income.

Voluntary organisations with an annual income of £1m or more account for 80% of the sector’s total income, yet make up only 3% of the total number of charities. Most of the UK’s largest charities, by income, are organisations that work nationally or internationally. They are predominantly charities that focus on health (including health research), children, disability or international relief. Cancer Research UK is the UK’s largest charity.

Medium-sized organisations are the only group to hold a percentage of the income (14%) that closely reflects the percentage of organisations within the sector (around 15%). Organisations in this category have an income of between £100,000 and £1m per year and are likely to include a local women’s aid charity or a national performing arts charity, for example.

Type of work of voluntary organisations

The NCVO’s Almanac considers the most common areas that charities in the UK work in by the amount spent. These are:

social services: by far the largest category of work, accounting for around 22% of the sector’s spending. Social services is a broad definition including organisations such as Barnados, Age UK and Crisis as well as charities engaged in emergency relief like the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI)

culture and recreation: the second most common category, with around 11% of spending, includes theatres, museums, galleries, sports clubs and zoos, for example the Royal Opera House, the Royal Shakespeare Company or the North of England Zoological Society.

The activities of voluntary organisations within their area of work vary, and can be summarised as:

providing a service: many charities offer a service directly to those they’re set up to support. Macmillan Cancer Support provide services to cancer patients, for example.

campaigning: some organisations find services only have a limited effect and that they can achieve a more significant impact by trying to influence others to change. For instance, Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) runs large public campaigns to change the opinion on smoking.

giving grants: some funders are charities themselves and provide grants of money to individuals or organisations to enable them to carry out their work, for instance the Garfield Weston Foundation or Comic Relief.

acting as umbrella or resource body: a number of voluntary organisations make a difference indirectly by supporting other charities to achieve their goals. For example, the National Council for Voluntary Organisations is a charity acting as an umbrella body with a goal to support and represent other charities. These umbrella or resource bodies are often called infrastructure organisations.

Voluntary sector workforce

The voluntary sector is a major employer in the UK, contributing 2.8% of the overall workforce. The number of people employed in paid roles in the voluntary sector is more than 827,000 – more than two and a half times the number employed by the UK's largest supermarket chain, and over half the number working for the NHS.

Apart from a small dip in 2010, this workforce has been steadily rising since 2002. This shows the voluntary sector to be an increasingly promising area for employment and career prospects.

Around two-thirds of the voluntary sector workforce are women, which is a similar gender ratio to the public sector but in stark contrast to the proportion of women employed in the private sector, which is just over a third. Voluntary sector employees are on average slightly older than those in other sectors, with almost two in five paid staff aged 50 and over. Almost two-fifths of the sector’s workforce work part-time, which is higher than in the public but less than the private sector.

Voluntary sector employees are mainly concentrated in small workplaces. Almost 60% of voluntary sector workers are in organisations of less than 50 employees, which is much higher than both the public and the private sectors. One-third of voluntary sector workers live in London or the South-East, reflecting the geographic distribution of voluntary sector organisations more generally.

Even though the voluntary sector employs a significant number of people, a lot of its power and impact comes from the work of volunteers. In 2016/17 around 11.9 million people (22% of the population) volunteered at least once a month and an even greater number, around 37% of all adults aged 16 and over, reported volunteering formally at least once in the previous year. This power is equivalent to 1.4 million full time employees to do the job, at an estimated value to the sector of over £22.6 billion per year.

Key challenges

The voluntary sector as a whole faces a number of general challenges that those working in voluntary organisations will need to consider if they are to try to overcome them in their specific context and carry out their work effectively. Some challenges have always been an issue for voluntary organisations, by nature of their place in society and their access to resources. Others change over time with new governments, technology and environmental or economic fluctuations.

Activity 3

Watch Karl Wilding, Director of Public Policy and Volunteering at NCVO, talk about some key challenges that the voluntary sector currently faces.

Transcript: Karl Wilding on voluntary sector challenges

While you are listening, note down the challenges that he raises. Once you have finished, note down two more challenges that you think the voluntary sector might face.

Discussion

The challenges that Karl Wilding raises are:

squeeze on income for the voluntary sector. Since 2008, after adjusting for inflation, the voluntary sector’s income has remained relatively static. Because the sector is delivering more and more public services through contracts, it is not able to build an asset base, meaning it can’t save and invest money that it can then use in the future.

increasing demand for services. Following the withdrawal of the government from providing services and support to those who need it, such as raising eligibility for services and reducing available benefits, there are more people who need support and they are coming to charities.

the blurring of the boundaries between sectors. The fact that people can be organised through social media, or make a difference in their day job or through corporate companies, leads people to question why we still need charities.

Some other challenges that the sector currently faces:

changes in government policy and law often affect the voluntary sector both directly, through their relationship with government, and indirectly, through the public’s relationship with the sector. For example, the Big Society ideology in 2010 had a big impact by increasing volunteer numbers and interest in voluntary organisations, but also by reducing investment in the structured voluntary sector. In another example, a Lobbying Act was introduced in 2014 which had implications for the voluntary sector as it placed some legal restrictions on their campaigning activity.

new technology offers a great opportunity to the voluntary sector in campaigning, organising people, marketing and providing services. However, it also presents a great challenge for organisations that don’t have the resources to invest in the equipment or training needed and so might get left behind.

demonstrating the difference they make is a key challenge for all voluntary organisations. Funders and donors are increasingly asking for evidence of the change that their money creates or will create. It is much harder for voluntary organisations to measure these changes than it is for private sector organisations to measure the profit they make.

voluntary organisations sometimes face criticism for not seeming ‘business-like’ enough and the risk is that they won’t be taken seriously. In 2014 a government minister, when faced with concern from charities about legal restrictions on their campaigning, famously suggested that charities should ‘stick to their knitting and keep out of politics’. The voluntary sector often works with some of society’s most serious issues and the challenge is for organisations to engage effectively with the private and public sectors and with the wider public whilst still retaining their values.

public trust and confidence in the voluntary sector is essential for maintaining donation levels, volunteer levels and engagement from those who need support. This trust and confidence was severely challenged in 2015 with public and media reports of inappropriate fundraising techniques by a small number of charities. This led to a call for more regulation around fundraising.

as more and more government services are being contracted out to independent providers, the voluntary sector is challenged to both collaborate and compete with private sector companies to deliver these services. Sometimes voluntary organisations are brilliantly placed to deliver these services, with their knowledge and contacts with those in need. But voluntary organisations often find it hard to navigate the complex systems that are set up to bid to deliver the contracts.

You may have thought of other challenges as well and this is by no means an exhaustive list.

All of the challenges raised in Activity 3 affect the voluntary sector generally, but different parts of the sector are affected more or less by each and also by their own specific challenges: for example, larger organisations are particularly affected by changes in public trust, and arts organisations are particularly affected by changes to government cultural policy. It is down to the people within those organisations to consider which are most pertinent and how to try to overcome them.

1.3 Values-based organisations

Some of the best-known voluntary organisations in the UK today have a long history and many were founded by philanthropists, religious organisations or other groups of concerned people as a response to the social problems of the day. They had usually identified a vulnerable group in society needing help, or a particular cause or issue that was not being addressed by government. Some organisations still exist to challenge and confront government and to campaign. This has traditionally given voluntary organisations a strong identity as being ‘values-based’, as well as the perception that all the staff and volunteers share particular values. However, the idea of values-based organisations is not exclusive to the voluntary sector, and in recent years the potential benefits of organisations developing and communicating their core values has been recognised across all sectors.

The concept of values is quite abstract and can be complex so you will look first at how values are defined, what individual values are and then move on to how they can be applied to organisations.

Defining values

Generally speaking, values are deep-seated beliefs about what is right or wrong and about what is important or unimportant. They are principles, standards or qualities that people care about and that contribute to driving people’s behaviour. Values held by individuals are also supported by a set of unwritten rules or norms about what is socially acceptable behaviour – both personally and within society. Values operate at different levels: individuals, groups, organisations or even societies.

Values incorporate a degree of judgement, and this further implies that people’s values are based on what is important as well as how important it is to them. Therefore, once people have ‘internalised’ a set of values, it becomes a standard for understanding the world around them, directing and justifying their own actions, sustaining their attitudes and, inevitably, judging others’ actions. Values can be abstract, such as freedom of choice, or specific, relating to hunger, poverty or racism for example.

Activity 4

Figure 7 above shows some examples of values. Identify the values you think you uphold, as well as those that go against what you believe in.

Discussion

Your answer to this activity will depend on your own set of values. You may find that you share similar values with your friends or colleagues: values are one aspect of which job we choose, where we work and the people we enjoy spending time with.

If you are passionate about animals, you might choose not to work for a company that tests their products on animals. However, not everyone has a choice in where they work.

Individual values

Values can impact on a person's interest in, and choice of, particular types of work and organisation. Individual values also impact on how they interact with other people who may or may not share their values.

Individual values stem from our social background, religion (if we have one), ethnic origin, culture, upbringing, education and our experiences of life and work. Individual values are not static. They continue to evolve during our lifetime as we experience new situations and people’s behaviours, particularly ones involving conflict or difference, or ones we find surprising or offensive. These encounters provide opportunities to question and rethink our own values. Of course, we may not be fully conscious of the values we hold or of the value judgements we are making when taking particular actions. We are also not necessarily consistent in our behaviour, and there may be a discrepancy between what we say our values are and how we act.

Values could influence your behaviour and actions in the following areas:

where you work or volunteer

who your friends are

how you interact with others

why you might have been in conflict with another person, your team or your manager (if you have one).

You can build on this by thinking about statements such as ‘I like volunteering for the local hospital.’ This is considered to be an attitude or preference rather than a value, and stems from a deeper desire to do some social good. Other factors may also influence actions: in this example, choosing to volunteer may also be about filling spare time or gaining skills that are useful for obtaining paid work. Therefore, theorists argue that values are the bedrock for attitudes, which guide people’s actions. A caveat to this statement is that people do not always act in a rational way: human nature can be inconsistent and contradictory.

Thinking about how values and attitudes influence or drive your behaviour can be important in a work context. Imagine you are asked to carry out a task that does not fit with your values. Would this result in conflict?

For some people in the workplace, there is such a mismatch between their own individual values and what they are asked to do (or something they have witnessed) that they are driven to the practice of ‘whistleblowing’. This might mean raising concerns within the organisation or reporting the organisation to the media. There have been many high-profile examples of this in the health service (poor care, abuse and neglect in Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust) and in technological scandals (Julian Assange and Edward Snowden). Legislation now exists in many countries to protect whistle-blowers and in the UK the charity Public Concern at Work provides support for them.

Values are just one component in people’s behaviour and actions: wider elements in an individual’s personality such as motivation, abilities, education and temperament also help determine their choices and areas of activity.

Organisational values

Much has been written about how values contribute to organisational culture in organisations across all three sectors (public, private and voluntary). Projecting an image of a strong organisational culture and a sense of shared values has been regarded as a useful marketing tool for organisations (Watson, 1996 cited in Hester et al., 2013, p. 306). In the context of the voluntary sector, voluntary organisations are often perceived to be particularly value-driven.

Organisational values may be similar to the types of personal values you have explored so far such as helping others, showing compassion, making a difference and so on. They are usually expressed in a more collaborative way, such as ‘we believe’ or ‘our objective is to…’ and so on. Just as personal values are the set of beliefs and principles guiding people’s behaviour, this also applies to organisations and how they work in practice.

In theory values guide organisations’ activities, services offered, recruitment and management policies. Statements of values explain to staff, stakeholders and the public what the purpose of the organisation is and what it stands for or what it feels is important. Sometimes an organisation’s values might be expressed as more ‘aspirational’, such as ‘This is what we want to achieve but we might not be there yet.’ Forrest et al. (2012, p. 1) at Cass Business School in London conducted a large-scale survey with detailed case studies on values in voluntary organisations. They found that the words most frequently used to express values were:

‘collaborate’

‘respect’

‘compassionate’

‘excellence’

‘professional’

‘creative’.

How do organisations communicate their values?

Organisations need to communicate their shared values in a way that its staff, volunteers and other stakeholders can understand and relate to. The most common approach is through its mission statement, website, social media websites such as Twitter and Facebook, advertisements for recruiting staff and volunteers and in fundraising campaigns.

The following extract highlights how all organisations (not just those in the voluntary sector) regard statements of values as important.

Box 1 Values-led businesses

Beyond pursuing success and profitability, organisations realised some time ago that their stakeholders needed them to be able to say: ‘This is how we do things here.’

It is hard now to find an organisation of any shape or size, from small NGOs to large corporates, which doesn’t publicly list its values, often quite prominently. Greenpeace International, for example, lists its values as: personal responsibility and nonviolence, independence, having no permanent friends or foes and promoting solutions. While Coca-Cola claims to be motivated by values of leadership, passion, integrity, accountability, collaboration, innovation and quality.

Similar lists can be found on the websites of virtually all organisations. The challenge is establishing what they mean and how stakeholders can ensure they are being lived and embodied, not just espoused.

Activity 5

Write down the most important values underlying the work of your organisation from published documents or your own observations. If you are not already working or volunteering, choose an organisation that you would like to work for and use their main website or what they put on social media sites to find the information about their values.

Has there been or can you foresee any conflicts that might arise between these different values?

Discussion

Your response to this task will reflect not only your own observations about your organisation and your colleagues but also your own values and attitudes. It might also have helped you to think about issues and values you had perhaps taken for granted. You may have struggled to find the information you need: perhaps if you work in (or chose) a small organisation, nothing is written down formally. This might have led you to think about whether that is appropriate and whether it affects staff/volunteer motivation or could impact on fundraising or seeking contracts.

Values in the voluntary sector

Having examined organisational values and how personal values fit with organisations, you will now focus on whether it is possible to identify shared values in the voluntary sector as a whole. Many discussions among researchers and voluntary sector practitioners about what is unique or different about the voluntary sector highlight that it is perceived to be values-driven, with staff, volunteers, founders, board members and other stakeholders sharing a set of core values. If values are at the heart of the sector, what does that mean given the diversity of organisations within the sector?

Values that could be considered common to the voluntary sector as a whole include honesty, participation, democracy, fairness, justice, accountability, equality, equity (fairness), compassion, freedom, empowerment, rights, solidarity, dignity, integrity, respect, trust, citizenship and tolerance.

The National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO) lists what it regards as the shared values for the voluntary sector:

Our values shape NCVO's culture.

They guide how we behave and make decisions.

We will;

use evidence. We base what we say and do on the best research and our members’ experiences.

be creative. We explore new ideas and approaches, looking for what will add real value.

be collaborative. We work with our members and partners to achieve the best results.

be inclusive. We value diversity and work to make sure that opportunities are open to all.

work with integrity. We are open and honest, and do what we believe is best for our members, volunteers and the voluntary sector.

Focusing on a sector as a whole inevitably involves making some general assertions. Not all of the values above would apply to all the organisations within the sector, but it gives a sense of the main purpose or direction for organisations considered to be part of this sector. Furthermore, having a set of shared values for the sector is perceived to give it an advantage over other sectors, which might be useful in bids for funding and contracts. It also builds an identity and set of goals that organisations, large or small, can share.

1.4 Key points from Section 1

In this section, you have covered the following:

All registered charities must show a public benefit; they are subject to laws, regulated by relevant bodies and overseen by boards of trustees; and are all voluntary in some way – that is, people give up their time through volunteering (bringing a wide range of skills and expertise to the sector) or they give up their money to further the cause.

There are over 166,000 registered charities in the UK employing over 880,000 people and involving over 11.9 million regular volunteers (with around two-fifths of the population volunteering on a less regular basis). But the voluntary sector is much larger than this, with an estimated 900,000 organisations working to make a social difference that cannot be accurately counted at this time. With an income of £47.8 billion and outgoings of £46.5 billion it is engaged in a huge variety of work in many fields, but does face a range of challenges today. The voluntary sector is predominantly made up of small organisations, with some of the few big charities becoming very large.

Values such as compassion, creativity or respect drive people's behaviour, guide organisations and unite the voluntary sector. It is worth considering the fit of your own values with those of voluntary organisations that you are interested in.

1.5 Section 1 quiz

Well done, you have now reached the end of Section 1 of Taking part in the voluntary sector, and it is time to attempt the assessment questions. This is designed to be a fun activity to help consolidate your learning.

There are only five questions, and if you get at least four correct answers you will be able to download your badge for the ‘Defining and exploring the voluntary sector’ section (plus you get more than one try!).

Now try the Section 1 quiz to get your badge.

If you are studying this course using one of the alternative formats, please note that you will need to go online to take this quiz.

I’ve finished this section. What next?

You can now choose to move on to Section 2, Money, or to one of the other sections so you can continue collecting your badges.

If you feel that you’ve now got what you need from the course and don’t wish to attempt the quiz or continue collecting your badges, please visit the Taking my learning further section, where you can reflect on what you have learned and find suggestions of further learning opportunities.

We would love to know what you thought of the course and how you plan to use what you have learned. Your feedback is anonymous and will help us to improve our offer.

Take our Open University end-of-course survey.

Glossary

- accountable

- Being responsible for, and able to explain and justify, actions taken.

- almshouses

- Homes financed by charities or philanthropists for people on low incomes. They were often financed by, and located next to, churches.

- asset base

- All the property belonging to a voluntary organisation. This includes investments, cash, land, buildings and vehicles, but it also covers the charity’s staff, volunteers, goodwill and reputation.

- beneficiaries

- Refers to service users, participants and so on, i.e. the people whom a voluntary organisation aims to benefit. The term incorporates a wider view however: if an organisation provides activities for children with disabilities, are the beneficiaries the parents or guardians of the children? Or the children themselves?

- Big Society

- An ideology based on empowering local people and communities to make change and decisions about services. It was a central theme of the Conservative party general election campaign in 2010.

- community group

- A social group whose members reside in a specific area and who come together to pursue a common interest.

- contract

- A written agreement enforceable by law. In the context of the voluntary sector, it usually relates to a specification for service delivery between a voluntary organisations and local or central government.

- customer

- The individual or organisation buying goods or services directly, without a contracting process.

- donor

- A person who donates something, especially money, to a voluntary organisation.

- empowerment

- Giving power or authority to others but also encouraging them to take power and equipping them with the skills, knowledge and confidence to do so.

- governance

- In terms of voluntary organisations it refers to all aspects of controlling, managing and leading organisations. It can also be applied at the national level and includes government and other authorities that run the country.

- grant

- A type of subsidy (money) given to a voluntary organisation by funders such as government, other voluntary organisations or private-sector organisations.

- housing association

- A non-profit organisation that rents houses and flats to people on low incomes or with particular needs.

- legislation

- A law or set of laws made by a government.

- norm

- Something that is usual, typical, standard or expected. Often used in describing society and expected behaviour or unwritten rules about behaviour.

- philanthropist

- Person engaged in philanthropy, which literally means ‘love of humanity’. It usually refers to people giving large sums of money to improve others’ welfare and wellbeing.

- social capital

- The trust, connections, bonds or ties between people in a place as well as the networks or organisations that bring people together. Where social capital is deemed to be low, people are perceived to be alienated and levels of prosperity and economic growth also low. Voluntary organisations often aim to improve social capital in areas.

- socially focused businesses

- A business that is created and designed to address a social problem. Most often, profits are reinvested in the business itself with the aim of increasing social impact.

- social enterprises

- Independent business that trades to deliver a social or environmental mission. Social enterprises aim to make a profit just like any other business. However, all profits or surpluses are reinvested back into their social or environmental purpose.

- special-interest group

- A community within a larger organisation with a shared interest in advancing a specific area of knowledge or learning.

- steering group

- A committee that oversees an organisation or project, provides advice where needed and ensures protocol is followed.

- sub-committee

- A committee composed of some members of a larger committee, board, or other body and reporting to it.

- trustees

- People who give their time for free to lead or steer voluntary organisations. Trustees set the direction for the organisation and are legally and financially responsible for it. Sometimes trustees are given other titles, such as governors, councillors, management committee members or directors.

- welfare state

- The UK is considered to have a welfare state, by which government takes responsibility for health and social care for all its citizens. It was originally perceived as a system whereby services would be provided free and paid for by National Insurance: the concept of free services has been eroded over the decades since it was first conceived in the Beveridge Report of 1942.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Julie Charlesworth (tutor at The Open University) and Georgina Anstey (consultant from the National Council for Voluntary Organisations).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Text

National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO) https://data.ncvo.org.uk/ (Accessed 29 April 2016).

Figures

Figure 1: © cnythzl iStockphoto.com.

Figure 2: © Everett Historical/Shutterstock.

Figures 3 and 7: © The Open University.

Figures 5 and 6: adapted from National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO) (2016a) UK Civil Society Almanac [Online]. Available at https://data.ncvo.org.uk/.

Video

‘Animation of key facts about the voluntary sector’ courtesy © NCVO https://www.ncvo.org.uk/.

Karl Wilding: © The Open University (2016).

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.