Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 1:46 AM

Accountability and communications

4. Accountability and communications

Introduction

Accountability is at the core of the work of voluntary organisations. In a broad sense, accountability means being held to account. In the sense of voluntary (and other) organisations, it means being responsible for actions taken by the organisation and also being able to communicate, explain and justify what they have done. Therefore, the organisation needs to be accountable to all its stakeholders – the people and groups who have an interest in what the organisation does, that is, service users, staff, volunteers, donors and members, funders, government, the wider public and so on.

Section 4 is divided into three topics:

- The role of trustees looks at the role trustees play in governance and strategy- setting. It also considers their responsibilities and the ways in which they are accountable.

- Know, grow and show the difference you make explains how voluntary organisations make an impact and how this activity can be planned, measured and communicated.

- Communicating with others explores what being a good communicator entails through examining different methods of communicating and how to improve the ‘message’. This can create more effective and accountable relationships with different audiences.

Learning outcomes

By completing this section and the associated quiz, you will:

- understand the difference between governance and management, and the role of trustees in voluntary organisations

- understand what is meant by the impact of a voluntary organisation and why it matters

- be able to improve the ways in which you communicate with others.

If you already work, volunteer or are a trustee then you will be able to apply the examples and knowledge gained to your own experience. If you do not yet work or volunteer in the voluntary sector then you could think about how these topics relate to an organisation you are interested in. You might even be inspired to consider applying for a role as a trustee, in which case you will have a clearer idea of what it entails.

4.1 The role of trustees

Trustees or members of the governing body play the key role of overseeing the organisation. They have specific responsibilities which they must carry out with the other members of the governing body, according to the organisation’s constitution and relevant legislation. All formal voluntary organisations have a ‘governing document’ which is called different things in different organisations, such as constitution, memorandum and articles of association, trust deed or rules. This document essentially contains the aims and rules of the organisation, lays out what the organisation will do and how it will do it, and illustrates how the organisation is democratic and accountable. If there are problems or questions about what the organisation has done, then it serves as a point of reference.

Governance relates to the systems and processes concerned with ensuring the overall direction, effectiveness, supervision and accountability of an organisation.

Good governance ensures that:

- the law and regulations are complied with

- an organisation is well run and efficient

- problems are identified early and dealt with appropriately

- the reputation and integrity of the sector are preserved

- charities make a difference and the objects of the charity are advanced.

Good governance involves:

- agreeing the purpose of the charity

- agreeing broad strategies to carry out the charity’s purpose effectively

- accounting for the non-profit’s performance

- ensuring it operates within the law.

Management, on the other hand, is about implementing the strategies agreed by the board, for example by detailed planning, putting procedures in place and raising money. Management and implementation is carried out by members of staff or volunteers. However, staff and volunteers may well contribute to governing and leading the organisation as well. There are inevitably exceptions, for example where trustees are also volunteers carrying out day-to-day duties in very small organisations; where the paid director of an organisation makes a substantial contribution to the strategic decision-making when meeting with the trustees; or where, in a very large charity where departments are devolved, they have considerable autonomy but this is usually still implementation and management rather than governing.

Who are trustees and what are their main responsibilities?

NCVO (2015) states that charity trustees are the people who are entrusted to look after money (or other resources such as land or property) given to a charity by a person or group of people. Charity trustees must ensure that these resources are used effectively to achieve the particular purpose for which they were given. Trustees are:

- voting members of the governing body

- elected or appointed in accordance with the charity’s constitution

- almost always unpaid

Trustees also have ultimate responsibility for everything the charity does and in a smaller organisation may delegate day-to-day tasks to staff and/or volunteers. This responsibility is not just at meetings but 365 days a year! This highlights what an important role being a trustee is. In a charitable company, company directors and trustees are the same people.

In thinking about their broader role, there are three essential questions for trustees to consider when governing a voluntary organisation:

- Why does my organisation exist?

- Where is it going now and in the future?

- Are we meeting our objectives in the most effective way?

The first of these questions relates to the impact and public benefit of the organisation; the second is about leadership, stewardship and strategy, that is, setting aims and objectives and priorities as well as safeguarding resources for beneficiaries; and the third is about stewardship and accountability. Again, this shows the importance and contribution of trustees in many different types of organisations in a range of fields.

Legal duties

The main legal duties for trustees of registered charities are laid down by the various Charities Acts in the UK and by the charity regulators. The key duties are to:

- ensure the charity is carrying out its purposes for the public benefit

- comply with the charity’s constitution and the law

- manage the charity’s resources responsibly

- act with reasonable care and skill

- act collectively

- ensure the charity is accountable.

There is a lot of guidance available on these issues (for example via National Council for Voluntary Organisations in England (see NCVO, 2015)) and the different charity regulators for the UK. The Wales Council for Voluntary Action also offers specific information and guidance. So if you are keen to become a trustee you might want to do some further reading (see the References at the end of this section). The charity you want to get involved with would also hopefully have information available.

Why be a trustee?

There is a shortage of trustees, particularly from younger age and more diverse groups.NCVO's Getting Involved report cities a survey giving the reasons for becoming a trustee included:

- a desire to become more actively involved in the community (22%)

- the chance to do something to progress a cause (17%)

- more meaningful way to support a charity than donation (17%)

- the chance to develop skills (17%).

These reasons might be similar to the reasons for volunteering in general, but wanting to be a trustee is quite different because of the large responsibilities and liability. People might not realise all of this when they first apply for a role.

Activity 1

Watch this video of Cara Miller talking about being a trustee and her own experience of it. Make notes on what she says is involved and consider the benefits and challenges of the role.

Transcript

A charity trustee is actually a really big responsibility an unfortunately I think far too often people go into it thinking it’s a lovely thing to do but without really understanding exactly what’s involved. Most charities actually limited companies and therefore by becoming a trustee you are a company director and you have to adhere to all of the legislation that involves. There is a duty of good care which means you have to apply yourself completely. Being a trustee would usually involve a lot of meeting attendance so you have they have to be very well prepared for those meetings and to make a contribution. If you have a particular skill or experience that you bring to the table you are expected to be able to provide that information and advice for the benefit of the other trustees. That said, whilst it is hard work is also rewarding and can be a lot of fun particularly if you are a trustee of a charity that you have a personal interest in. I am a trustee of ‘Healthy ambitions’ in Suffolk which is a charity that aims to improve the health of people in the county and also reduce the health inequalities that exist within the population. My job is as Chair of the charitable giving committee, so my role is to spend the money of the organisation on grants to help us achieve our aims and one of those last year was funding breakfast clubs in schools in areas of deprivation. So we would help ensure that children were starting the day with food in their tummy’s so they are able to concentrate and I got to go along to two or three of those breakfast clubs and get involved and it was really good fun! So you do get brilliant opportunities like that, that you wouldn’t otherwise. I also think for young people being a trustee is an excellent opportunity. There are not very many young trustees and young people can add a lot to a board that can sometimes get overlooked. It is also really good experience to get used to attending meetings and seeing how decisions are made and discussed at board level.

Discussion

Cara highlights the issue that often people do not know what they are taking on. She says that being a trustee involves having a duty of care, complying with regulations, going to meetings and being well prepared; also that people need to be confident in sharing their skills and experience with the other trustees. She says that it can be a very rewarding experience and talks about how interesting she found seeing how the money was spent by her charity (which she did by setting up breakfast clubs). She also highlights how useful it would be if there were more young people as trustees: it would be good experience for them and the charities.

If you are interested in applying to be a trustee, you should ask yourself the following questions to reflect on whether you have the right aptitudes, skills and experience.

Box 1 Finding the right fit

- What are your motivations for wanting to be a trustee?

- Are you committed to the objects and values of the charity?

- On what level does the charity operate (international, national, local)?

- What does the charity do, for example campaigning, service delivery, policy, research?

- What will be expected from you?

- Is the charity financially sound?

- What is the size of the charity and what are its potential liabilities?

- What policies are in place to deal with risk?

- Who else is on the board? Can you meet them?

Activity 2

Imagine that you want to be a trustee (if you are already a trustee, reflect on what you thought about when you first applied). Write notes on the questions in Box 1 and reflect on which ones would be the most important for you personally.

Discussion

Your answer will be personal to you, but your main motivations may be that you support a particular cause and feel passionate about the values of a particular charity. You might even volunteer for the charity already and feel ready to help with its governance. You might also want to increase your own skills and experience because you want to look for paid work in the voluntary sector in the future. Knowing more about the charity and about what is expected of you (how many meetings a year, how much reading/preparation is involved, whether expenses are paid) is very important. Looking in more detail at the finances and legal aspects would definitely be important. You could find out much of this by talking to existing trustees and also get a sense of whether you would be happy working with them.

Box 2 provides the example of Angela, who became a trustee and was able to use her existing professional skills and experience and apply them to a different context. When advertising for new trustees, organisations often specify particular areas they wish to recruit to: for example, fundraising, finance, managing change, partnership working or networking and so on. In addition to the relevant specialist skills and experience, the following would also be relevant: good communication skills, being able to reflect on your work, being willing to learn and ask questions, a good listener and skills in chairing meetings.

Box 2 Example of a trustee’s contribution

Angela Beagrie, Head of Compliance with NHS Stockport Clinical Commissioning Group, was delighted to see a volunteer opportunity posted on a social media site by Reach that was just what she was looking for. She was keen to use her professional skills to help a charity that needed those skills to succeed.

Via Reach – which promotes skills-based volunteering – Angela was appointed as a trustee for Independent Options, a charity providing a range of services to people with learning disabilities in Stockport, Trafford and sections of Greater Manchester.

Jim Grassick, chair of the charity’s board, says, ‘In Angela’s case, we were looking for someone who might help us in our dealings with local members of Parliament as we tried to publicise the plight of some of our users’ parents, who we feel are unjustly treated by the local authority. Not deliberately, but by accident as they are lumped together with everyone else. Angela brought this experience. She had worked as a Special Advisor in the political office in No. 10 Downing Street, advising on lobbying strategies.’

’However, Angela has brought a lot more to the charity. She has experience of writing company strategies. She is focused on turning information into actions.’

’It’s fantastic,’ Angela says of her appointment, ’I’d only been there a few months and already helped to write their strategic plan. I’m now working on a campaign to get the support of the local MPs for the issues affecting the families we work with.

’I didn’t realise so much was going on locally. There were so many opportunities and charities that need the skills you can offer.’

Reach (2016b) summarise the issues around eligibility, that is, who can become a trustee. Most people over 18 years of age can become trustees, except those who have already been disqualified as company directors and those who have been convicted of an offence involving dishonesty or deception.

Applying to be a trustee is similar to a job application: it may involve a letter of application, your CV and an interview.

As well as making a difference, being a trustee can provide considerable experience if you are interested in building a CV suited to working in the voluntary sector. However, trustees cannot go on to be employed by the organisation where they are a trustee.

You will finish this topic by thinking about what it is like to be a member of staff or a volunteer in an organisation where there is a threat to accountability and the impact on the organisation and its stakeholders.

Activity 3

Imagine you are working or volunteering in an organisation where the trustees do not seem to be in control of finances or strategy. Write down three things that would concern you, for example the impact on the organisation’s purpose, service users, staff, volunteers, wider support.

Discussion

The main issue of course is the impact of poor governance on the service users and other beneficiaries. Other concerns could include: impact on the levels of donation and support from members of the public; poor publicity; volunteers or staff leaving and difficulties in recruitment; difficulty in getting contracts or grants; intervention by the charity regulator or legal issues. In terms of concerns about your own role, if the trustees asked you for information you might be unsure how much you should complain about the lack of direction. You might wonder whether you should ‘whistleblow’, going outside of the organisation to alert another authority about the situation.

4.2 Know, grow and show the difference you make

With limited money in the voluntary sector it is vitally important to take time to consider whether you are making the biggest difference you can with the resources you have.

The difference that a voluntary sector organisation makes to people, communities or the environment is called its impact. An impact could be anything from reduced isolation of older people in Wolverhampton to a greater number of puffins in the UK, for example. Achieving its impact is the ultimate purpose of the voluntary organisation; it is why it exists. Impact is the profit of the voluntary sector.

To achieve its impact a voluntary organisation produces products and services. It might produce services such as a parenting class for new parents or products such as an audio book for people with sight loss, for example. These products and services are called outputs. They aren’t produced for the sake of providing services, but as a way of achieving the organisation’s impact.

This distinction between what a voluntary organisation produces (outputs) and what it achieves (impact) is important. Being clear on this distinction means that you are better able to think about why you are doing the things you do and to consider or even measure whether they are working and if they could be done better.

Activity 4

Read the statements below and decide whether each statement relates to the output or the impact of a youth centre in Barnsley:

- a games session on Saturdays for 12–16 year olds

- reduced local vandalism committed by young people

- 75% of young people have new friendships

- a table-football table

- five one-to-one sessions with a youth worker

- increased confidence.

Discussion

The following relate to the outputs (products and services) of the youth club:

- a games session on Saturdays for 12–16 year olds

- a table-football table

- five one-to-one sessions with a youth worker.

The following relate to the impact (difference made) of the youth club:

- reduced local vandalism committed by young people

- 75% of young people have new friendships

- increased confidence.

There are lots of reasons to keep a focus on your impact, as well as your outputs. Not least among these is that a voluntary organisation’s funders or donors will be interested in it and will often require evidence of the difference you are making with their money.

Focusing on the impact your project or organisation makes will help you to:

- make decisions: choose the work that is most likely to make the difference that you want and work out how to measure it

- improve: make changes to your work based on knowledge of what is working well or not so well and what makes the biggest difference

- be accountable: provide information to your funders or donors of the difference that you plan to make and are making with their money

- engage people: remind staff, volunteers and funders why they do it and inspire others to take part or support you too.

In order to really focus on the impact of your project or organisation you will need to first plan what difference you want to make and how to measure it. The next step is to measure the impact and analyse the results. Finally, you work out what learning you can draw and communicate the results to others. These steps will now be explained in more detail.

Planning your impact

Voluntary organisations are often addressing urgent needs in the people they work with, for instance supporting someone with nowhere safe to sleep that night or someone who feels suicidal. It can be all too easy to get caught up in working with the people who come to you first or working in the way that your funders want or you have always done. It is important to take a step back and plan what difference you want to make so that you can make decisions about which work to take on.

The first stage of planning your impact is to be clear on who you are there to make a difference to. The people or animals who will benefit from a voluntary organisation’s work are referred to as the beneficiaries. Beneficiaries are often described in groups such as: ‘older people in Wolverhampton’ or ‘children and young people (6–16) with mitochondrial disease’. Being clear on who you are there to support helps you to focus on where to spend your resources.

You can then consider what difference you want to make to those people or animals. It is best to use words that express that a change has happened, such as: increased, reduced, more, less, higher, lower, greater or fewer. For example:

- reduced isolation among older people in Wolverhampton

- older people in Wolverhampton have a greater awareness of local services

- older people in Wolverhampton feel more confident to leave the house

When working out how to measure whether or not you have achieved the planned impact then you should think about what you could count, collect or observe as signs of that change. Finally, you work out the best way to gather that information and who should do it. For example:

| Impact we want | What we will count, collect or observe (signs of impact) | How we will gather information (methods) |

| Reduced isolation among older people in Wolverhampton. | Number of people that older people have spoken to in the last week. | Ask them by telephone before and after they attend our lunch club. |

| Older people in Wolverhampton have a greater awareness of local services and events. | Whether or not older people know about:

| Ask them by telephone before and after they attend our lunch club. |

| Older people in Wolverhampton feel more confident to leave the house. | How confident they say they feel on a scale of 1 to 10. How confident they seem when leaving the house. | Ask them by telephone before and after they attend our lunch club. Ask the volunteers who collect them what they think. |

Measuring your impact

Measuring your impact is more complex than counting the income that you raise, or the services you deliver, but it is possible in even the smallest voluntary organisation.

There are many methods of collecting information to measure a voluntary organisation’s impact depending on their work, budget and whether they need numbers or stories. Popular methods for measuring impact include questionnaires, interviews, focus groups or evaluation forms. You can also look at existing data you haven’t collected yourself, such as that held by the government, or use more creative methods like video, pictures or diaries. Finally, don’t forget the informal things that you or your volunteers observe in your work.

The process of collecting this data is called monitoring. The process of drawing conclusions from the evidence you have and making judgements about it is called evaluation.

You don’t need to be a researcher to monitor and evaluate your impact. Sometimes complicated or long-term impacts can feel hard to measure, or you might feel that you cannot tell if an impact was definitely a result of your work. But you don’t have to look for scientific proof of your impact: your responsibility is just to look for the best possible evidence you can find with your available time and money. There are many resources available within the voluntary sector to guide you on this, for example from NCVO Charities Evaluation Services or from Evaluation Support Scotland.

In this video the Chief Executive of Evaluation Support Scotland covers some of the concerns that voluntary organisations raise around monitoring and evaluation of their impact in a light-hearted and amusing way:

Transcript

But now for something completely different.

Gene was glum. Her funds were tight. She felt she could do nothing right. Can’t prove her impact show success. A last resort – phone ESS. Directly I burst through the door, sprinkling post-its on the floor. Gene was filled with fear and dread, as I grabbed a flip-chart pen and said ‘Let’s do it! Let’s do it! Common, lets evaluate, reflecting, perfecting. Your evidence would then be great. Don’t wrangle, I’ll disentangle. I’ll really get you going with my weaver’s triangle. Let’s do it! Let’s evaluate.’

But Gene said – ‘I can’t do it, I can’t do it! Measure just makes me cry. It’s boring, I’m snoring, I do not even want to try. My funder just want numbers and evaluation might just show up all my blunders. I can’t do it, I can’t evaluate!’

So I said – ‘Let’s do it, let’s do it! I don’t just mean a questionnaire. Creative, innovative, so many different tools out there. So tap in, no flapping, I’ll thrill you with before and after body-mapping. Let’s do it! Let’s evaluate!’

But Gene said – ‘I can’t do it, I can’t do it! Evaluating is just a game. Your words are just absurd – objective, output, outcome, aim? You’re losers, confusers, and I really don’t want feedback from my service users. I can’t do it. I can’t evaluate!’

But I said – ‘Let’s do it, let’s do it. Evaluation must be done. The fact is – it’s good practice. Honestly, it will be fun. Not what-twoddle, a doddle, I’ll blow your mind when I whip out my logic model. Let’s do it. Let’s evaluate!’

‘I can’t do it, I can’t do it! I have cupboards full of useless stats that I’ve gathered, hap-hazard, for countless council bureaucrats. I’m luke-warm. I won’t conform, I pulled a muscle filling in that lottery form. I can’t do it. I can’t evaluate!’

‘Let’s do it, let’s do it! You want to show you’ve made the grade. Your task is to ask what difference you have really made. Let’s plan, it’s no scam. You know that all the ladies call me Outcome-man! Let’s do it, let’s do it! Let’s evaluate.’

‘I can’t do it, I can’t do it! I don’t have the skills or the support. I’ve concluded, it’s stupid since funders won’t read my report. They ignore me, or bore me. Why can’t bloody ESS just do it for me? I can’t do it! I can’t evaluate.’

So I said – ‘Let’s do it, let’s do it! I promise that you won’t be scared. I’m yearning for learning. Do you like your outcomes soft or hard? Dogmatic, fanatic. Measuring my impact makes me feel ecstatic. Let’s do it. Let’s evaluate!’

One more time – ‘Let’s do it, let’s do it! Policy makers want it now. Let’s mention prevention, you could show them why and how. Solution, contribution. Your evidence could really start a revolution. Let’s do it. Let’s evaluate!’

Thank you very much!

Activity 5

Communicating your impact

Once you have measured your impact, it is important to tell people about your results. If you have made a difference then your results can be used to promote your organisation, motivate staff and let others know what works.

It is also important to share your results even if you haven’t made the difference you hoped. Although this can feel daunting, it allows others to learn from them and helps them to feel that you are an honest and transparent organisation. Ultimately your aim is to make a difference to your beneficiaries, so sharing your impact in this way enables voluntary organisations to work together to make an even bigger difference for those people or animals.

People who might be interested in hearing about your results include:

- funders and donors

- staff and volunteers

- beneficiaries

- other voluntary organisations working in a similar area.

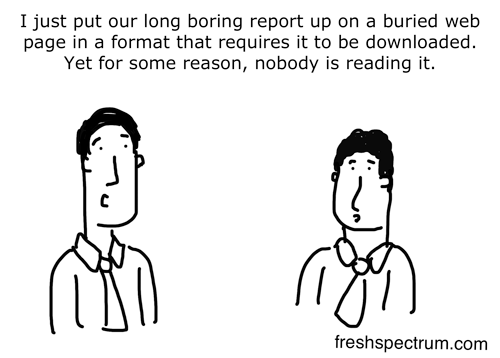

The traditional way for voluntary organisations to communicate the results of their impact measurement is in a report – sometimes called an impact report, evaluation report or annual report. However, there are lots of other less formal ways to share information about impact including on a website, in a presentation, through social media or verbally. It is good to make sure that your results are published in a way that people want to receive them and are more likely to read them.

Activity 6

Read the text below from a charity summarising and reflecting on their work and impact in the last year. See if you can identify the following aspects of their work:

- who their beneficiaries are

- what outputs (products or services) they provide

- what impact they have

- how they measure their impact.

Box 3 Reflecting on the past year

English for Action is a charity providing free ESOL classes (English for Speakers of Other Languages) for adults across London. All of our participants are migrants who have English as an additional language. Over the last year our lessons and workshops have been delivered in locations accessible to the participants, such as primary schools, community centres, faith organisations and workplaces. Our courses are free for all participants irrespective of their income, immigration status or nationality.

Last year, over 345 people attended our 18 ESOL courses in the London boroughs of Greenwich, Southwark, Wandsworth, Tower Hamlets and Lambeth. More than 50% of these were receiving ESOL support for the first time. Participants use our classes to learn language, make new friends, find out about local services and to take action that brings about positive change for themselves and the wider community.

In this last year, we have delivered our services through one full-time co-ordinator, 8 part-time teachers and 19 volunteers. We raised over £109,000, including multi-year funding from the Walcot Foundation and Esmee Fairburn.

We asked all of our participants to complete an evaluation form at the end of their course and 97% ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that they had improved their language skills as a result of attending. This supports the results of the informal assessments carried out by our teachers and recorded in the students’ portfolios which showed a profound improvement in language skills. In addition, 151 of our participants achieved an externally accredited ESOL or English Skills qualification.

In the last year we ran 15 class trips to places such as Kew Gardens, Greenwich, Tower Bridge and the South Bank Centre. 91% of participants reported in their evaluation forms that they had made new friends through these trips and the courses in general.

In our classes we discussed and shared information about many local issues that affected our participants including finding work, using libraries, housing, local transport, childcare, benefits, doctors’ surgeries and more. In their evaluation forms, 90% of participants reported that they had a better knowledge of services and facilities in their area after attending our courses. Students often used the words ‘confident’ and ‘confidence’ to talk about how they feel about using the services after the class.

Next year we hope to sustain our existing provision of ESOL classes, support more participants to make changes to improve their living conditions and campaign for wider access to ESOL across the UK.

Discussion

- Who their beneficiaries are:

- their beneficiaries are adult migrants living in London who have English as an additional language.

- What outputs (products or services) they provide:

- they provide ESOL classes and class trips.

- What impact they have:

- participants have improved language skills

- participants make new friends

- participants know more about the local services in their area and feel confident about using them.

- How they measure their impact:

- participants fill out evaluation forms after their course

- teachers complete informal assessments of the participants

- some participants achieve an externally accredited qualification

- teachers listen to the words students use to talk about how they feel after the class.

4.3 Communicating with others

A key skill often mentioned in a person specification in the voluntary sector is ‘being a good communicator’. What does that really mean and why does it matter? There are many different ways of communicating at work: speaking to others on a day-to-day basis, at appraisals and in supervision meetings; consulting volunteers individually or in a group; writing clear reports, letters, concise emails, texts and social media messages; and, just as important as speaking and writing, listening to others.

Developing your personal communication skills in a variety of contexts and with different audiences (such as service users, volunteers, trustees, staff, other organisations, funders, public meetings, politicians) can help you work more effectively with other people. Furthermore, good communication skills are part of accountability, in terms of how you inform, consult, negotiate and –where necessary – influence others.

How do people communicate?

The effective development of relationships requires you to communicate well, be organised and draw on skills that you might already have such as self-awareness, empathy with others, and so on. Whether you are working in a team, exercising leadership, managing your family or managing others’ work you will need to develop skills to work effectively with others.

Many of the skills involved relate to the process of communication. Talking and listening may be something you do every day, but most of us do not think about the process and therefore may not go through the loop necessary for learning to communicate more effectively. If you are a supervisor or manager, sometimes you may need assertiveness skills and working with others will additionally require you to be good at delegation as well as engaging with and developing your team.

The idea of information lies at the heart of communication. Information may be thought about in different ways. Some information may come as a surprise or as something more predicted, and some information may help to reduce uncertainty. It helps to think of information content in terms of its usefulness.

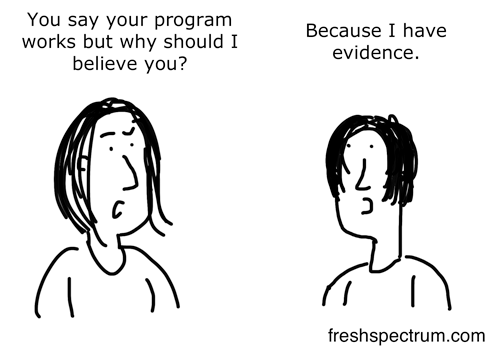

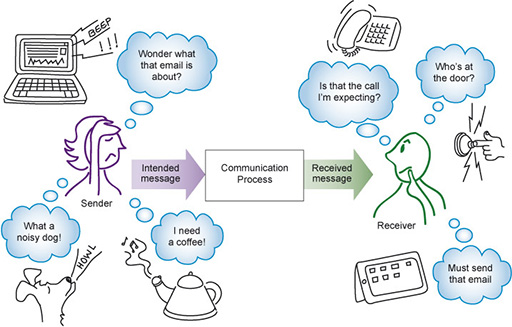

If you have a poor signal on your mobile then the noise of it breaking up might make it difficult to work out the words of the speaker. Figure 5 suggests that for everyday communication noise is not limited to the channel but is also subject to other distractions that limit concentration.

When talking to someone face-to-face your body language and tone of voice will probably be carrying far more information than the words you are speaking. Email is a particularly hazardous form of communication as the signal is limited to words and emoticons.

Whatever the means or channel of communications, you cannot know whether your recipient will be using the same assumptions to interpret your message as you were using when you ‘encoded’ it into words. Sensitivity to a recipient’s values, expectations, beliefs, prior knowledge and emotions can help you to put your message into words that are likely to convey the meaning you intended. Misunderstandings are particularly likely when the recipient thinks they know what you are likely to say, and hears what they expect, even if it is a long way from your intended message.

Having delivered your message, you can’t just assume it has been received in the way you intended. People don’t just passively receive messages: they actively select, filter and interpret them. If people do not think a message is likely to be interesting or important they may ignore it altogether, their minds may wander or they may switch their attention elsewhere.

Think about the implications of this for how you convey your organisation’s message or aims. For example, a person who believes passionately that there is an environmental crisis is likely to understand and respond to a campaigning leaflet from Friends of the Earth differently than someone who is highly sceptical.

Activity 7

Imagine you are a volunteer co-ordinator in a voluntary organisation and you’ve been asked to brief the other volunteers about some changes in how rotas will be organised. What might you do to prepare and communicate this message to this group?

Discussion

In order to communicate, we have to give expression to half-formed thoughts and ideas by putting them into acceptable words. It is often only in the process of expressing our ideas that we clarify our own thoughts.

This has implications if your message is at all complex, as in this example (since people are often fearful of or resistant to change). You will need to express, clarify and polish your ideas before communicating them. For written communication this usually involves a process of drafting and redrafting. Even for verbal communication you might want to make notes of the main points you want to communicate and – if it is important – practise saying them.

So thinking through which means of communication might be best for your message – such as email, a text, a phone call, a message on social media or a newsletter – is very important. The medium constrains and shapes the message that can be sent: for example, what you can say in a text is very different from what you can say face-to-face. How well a medium is used can also give authority to your message or undermine it. For example, a confident, well-delivered presentation may add weight to your message, whereas a poor presentation may undermine it.

The message in this example would probably be better communicated via a face-to-face meeting, as it is likely to generate discussion and possibly disagreement. It could otherwise be done by email or even individual phone calls.

Listening to others

All too often, ‘listening’ is not wholly focused on the speaker. At a party your ‘listener’ may be looking over your shoulder to see if there is someone else they want to talk to. In a meeting your colleagues may stop listening because something you have said has started them thinking in more depth. Or you may have said something they disagree with and they are already trying to work out how to argue with you. Or they may simply be looking out for a gap in your talking so that they can make a point they have been waiting for ages to make. They may even be completely uninterested in what you have to say, and planning tonight’s evening meal!

A good listener will ‘listen’ to all aspects of the communication: the words, the tone of voice and the body language. Their attention will be fully on the person speaking and their main purpose will be to fully understand the speaker’s meaning. This sort of active listening is part of demonstrating empathy. A good listener might nod and smile as a way of encouraging the speaker. This is an important skill to exercise if the speaker lacks confidence or experience and needs encouragement, particularly in public meetings. See Box 4 for the key aspects of active listening in different contexts.

Box 4 Active Listening

Demonstrate that you are listening

Use your own body language and gestures to convey your attention. If your arms are folded or you are looking around you or reading your papers, you will not look like you are paying attention.

Show you are actively listening by:

- nodding occasionally

- smiling and other positive facial expressions

- mirroring the other person’s body language

- noting your posture and making sure it is open and inviting

- encouraging the speaker to continue with small verbal comments like 'yes', and 'uh huh'.

Demonstrate that you understand what is being said

As a listener, your role is to understand what is being said. We all have personal filters, assumptions, judgments and beliefs that can distort what we hear.

Show you understand what is being said by:

- reflecting back from time to time on what is being said. Saying something like: ‘What I’m hearing is…’ or ’It sounds like you are saying…’ are good ways to reflect back

- asking questions to clarify. Asking something like: ‘What do you mean when you say…’, ‘Is this what you mean?’ or ‘Can you give me an example of…’ can help

- summarising the speaker’s comments periodically.

Respond appropriately

Active listening is a model for respect and understanding. You are gaining information, perspective and context. You also need to respond appropriately.

What can help is to:

- be candid, open and honest in your response

- assert your opinions respectfully

- treat the other person as he or she (or you!) would want to be treated.

Meetings

Meetings are an inevitable part of organisational life and they are a crucial aspect of communicating well both for the chair of the meetings and the participants. Providing information and consulting are key elements of voluntary organisations being accountable. For example, meetings allow issues to be discussed, information provided, different groups consulted, positive or difficult feedback given in supervision or appraisals, staff motivated and change communicated. In the past, meetings often took place in formal settings such as offices and meeting rooms and nearly always involved people meeting ‘face to face’. Times have changed though and meetings are just as likely to be in a café or all the participants joining the meeting by phone or video calling. Much of what has been covered here on communication will relate to meetings in terms of ensuring your message is clear and developing listening skills.

Activity 8

- Think about a meeting that you have been involved in that went really well. List the reasons why you think it worked well.

- Think about a meeting that you have been involved in that did not work well. List the reasons why you think it worked poorly.

Discussion

Your answer will relate to your own experience, but reasons why meetings might go well include:

- the meeting has a clear purpose and the appropriate people are present

- people are prepared for the meeting

- the agenda is not too long

- the chair ensures that discussion keeps to the main issues, provides useful summaries of progress and makes sure people keep to the point

- people trust and respect each other’s opinions.

Conversely, some of the reasons why meetings do not go so well are:

- the agenda is very long

- the chair allows some individuals to dominate or not keep to the point and does not keep to time

- people are poorly prepared for the meeting, perhaps not having papers in advance or not having read them

- the meeting goes on too long without a break.

You may have thought of some other reasons why meetings are successful or not.

Meetings are a central part of running many voluntary organisations. However, meetings do have a tendency to take on a life of their own. As a result, it is worth asking periodically whether particular meetings are necessary or whether other means could be used to achieve the same ends, without compromising good communication between different groups.

Some of the possible advantages and disadvantages of meetings are shown in Box 5.

Box 5 Some advantages and disadvantages of meetings

Advantages – meetings can:

- improve decision-making by involving more points of view

- give a shared sense of ownership and commitment among participants

- facilitate good communication

- keep managers, staff and volunteers in touch with one another

- keep the organisation’s membership or service users involved

- help improve the communication and decision-making skills of those involved.

Disadvantages – meetings can:

- tie up people’s time, taking them away from other work

- be expensive – eight people meeting for an hour is the equivalent of a day’s work

- reduce speed and efficiency – decisions can take a lot longer if it is necessary to wait for a meeting, and in the meantime opportunities may be lost

- lead to poor decisions or delay because of the need to try to reach agreement among many people

- dampen individual initiative and responsibility if too many decisions are taken by meetings.

Activity 9

Think about two or three meetings in which you have been involved. For each meeting answer the following questions.

- How necessary do you think the meeting was?

- Could some or all of its work have been carried out in other ways?

Discussion

Meetings are only one way of dealing with work, so it is important to think about whether alternatives may be better. For example:

- some decisions can be delegated to individuals rather than taken at meetings

- information can be shared at meetings but can also be disseminated in a variety of other ways: through notice boards, newsletters, email, websites, online discussion groups, etc.

- consultations can also take place through one-to-one meetings, telephone calls, computer conferencing and emails

- support can be given through individual supervision or peer support as well as in groups.

Even when meetings are necessary it is worth asking whether everyone has to be physically present in the same room, particularly where this would involve people travelling long distances. It may be more efficient to hold a telephone or computer conference for some or all of the participants. Whatever the format of the meeting, all of the elements of good communication need to be put into place.

4.4 Key points from Section 4

- Voluntary organisations are governed by a board of trustees and have a governing document (called a constitution here). Trustees have a duty to be accountable and also have legal responsibilities for their organisation. There are many reasons why people wish to be trustees, including making a difference and building their own skills and experience for working in the voluntary sector.

- Voluntary organisations seek to make an impact through the work that they do. Being clear about impact, in addition to outputs, contributes to the organisation’s accountability. Planning impact is important, as is being able to measure it. Communicating the results of the organisation’s impact to different audiences effectively is also a key element of their work.

- Being a good communicator is considered a key skill in many roles in the voluntary sector because of its contribution to working well with others and to accountability. People communicate through talking, listening and writing in different channels and styles and with different audiences. However, the message being conveyed may be received differently from how it was intended. Learning to listen actively is a key skill in helping the communication process and in helping others to have a voice at meetings. Meetings, which are one means of communication, are still important in organisations for reasons of accountability, consultation and communication, but they need thought and planning in order to work effectively.

4.5 Section 4 quiz

Well done, you have now reached the end of Section 4 of Taking part in the voluntary sector, and it is time to attempt the assessment questions. This is designed to be a fun activity to help consolidate your learning.

There are only five questions, and if you get at least four correct answers you will be able to download your badge for the ‘Accountability and communications’ section (plus you get more than one try!).

- Now try the Section 4 quiz to get your badge.

If you are studying this course using one of the alternative formats, please note that you will need to go online to take this quiz.

I’ve finished this section. What next?

You can now choose to move on to Taking my learning further where you can reflect on what you have learned, obtain your Statement of Participation for the course and find suggestions of other places you might like to visit.

If you have not done so already, you might like to visit one of the other sections so you can continue collecting your badges.

We would love to know what you thought of the course and how you plan to use what you have learned. Your feedback is anonymous and will help us to improve our offer.

- Take our Open University end-of-course survey.

Glossary

- charitable company

- A charity registered both at Companies House (as a company) and with the Charity Commission as a charity in its own right. (Compare this with an incorporated charity: a charity form that has its own legal personality enabling it to enter into contracts and to limit the liability of the trustees. A charity that employs staff, leases a building or enters into any kind of contract then it is likely to be incorporated.)

- constitution

- A type of document setting out an organisation’s purposes and rules. This is the most commonly known name for a governing document. For some organisations this document may be called ‘memorandum and articles of association’, ‘trust deed’ or ‘rules’ instead.

- governing body

- The group of people (often called the board of trustees) who control, manage and lead a voluntary organisation.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Julie Charlesworth (tutor at The Open University) and Georgina Anstey (consultant from the National Council for Voluntary Organisations).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Text

Box 2: extract from Reach (2016a) Success stories [Online]. Available at https://reachskills.org.uk/ knowledge-centre/ success-stories/ trustees/ angela-and-independent-options.

Box 4: extract from Knowhow Nonprofit (2016) NCVO/Knowhownonprofit [Online]. Available at https://knowhownonprofit.org/ people/ your-development/ working-with-people/ listening.

Figures

Figure 1: cacaroot/iStockphoto.com.

Figures 2 and 3: © Chris Lysy, https://gumroad.com/ l/ freshspectrum.

Figure 4: logo, English for Action; accompanying text adapted from English for Action.

Figure 5: © The Open University.

Videos

Activity 1: script by Cara Miller, Miller Wash Associates.

Section 4.2: video and script courtesy Steven Marwick, Director of Evaluation Support Scotland.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.