Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:23 PM

1 What is ‘open’ education?

1.1 Introduction

This section of the course will look at what meaning ‘open’ might have in different contexts, what makes an educational resource or practice ‘open’ and open licensing.

- What does openness mean and how does it impact on practice?

- What is an ‘open’ educational resource or practice?

- What does an open licence look like and what does it do?

Learning outcomes

- have a better understanding of what makes a practice or resource open

- understand what are the different types of educational resources

- have an awareness of the different types of Creative Commons licences.

1.2 What does ‘open’ mean?

What does it mean to describe an educational practice or educational resource as ‘open’? In part, this depends on the definition of ‘open’ you are using, but it also reflects the context you are working in or referencing. To start thinking about openness, let’s introduce some of the characteristics usually associated with this concept.

Access

Open is often associated with increased access to resources. In particular it is associated with open access and the drive to ‘open up’ academia by publishing research outputs on an open licence. Access to research is increased because resources might not have previously been available and potential users do not need to pay to view or use materials (e.g. resources are not behind a paywall). Increasing access to a resource can also refer to the way a resource is displayed or presented. For more on accessibility see Section 3.5.

Transparency

‘Open’ is often associated with increased transparency, for example in relation to one’s own practices or data. This is particularly the case when one shares data, research and materials with others and by doing so enables public scrutiny of processes, outputs and assertions. For example, making datasets openly available allows others to check for errors, carry out different or the same analyses and ultimately develop and improve research further.

A wide range of government bodies, organisations and foundations support increased or open access to research or data through policy or by funding projects, networks or initiatives that develop open materials or practices. These include the Scottish Funding Council which funds projects such as Opening Educational Practices in Scotland (OEPS) and Open Scotland which is supported by The University of Edinburgh and other organisations, including OEPS. The Wellcome Trust and Research Councils UK (RCUK) have open access publishing policies. Open Knowledge Foundation Scotland is a third-sector organisation that promotes, connects and supports open education initiatives across Scotland.

Free

The term ‘free’ is often used in relation to open educational resources (OER). But what does ‘free’ mean within the context of ‘open’?

As noted above, increasing access to resources often involves removing the need to pay for a resource at the point of use. This type of ‘free’ has been described as ‘gratis’, as the user is not charged a fee to access or use the resource. Any costs associated with a resource’s creation and/or maintenance are absorbed elsewhere, for example by the creator or funder. (OER projects and providers are often supported by philanthropic organisations such as The Hewlett Foundation or the Gates Foundation.)

Another meaning of ‘free’ within the context of openness is ‘libre’. If a resource is ‘libre’ it doesn’t have limitations on the way in which you can use it. Within the context of openness this refers to the potential of openly licensed materials to be reused. However, different licences afford the user different levels of reuse, and some are not considered to be ‘free’ in the ‘libre’ sense. Open licensing is discussed in more detail in Section 1.5. In the meantime, if you are interested in finding out more about the distinction between ‘libre’ and ‘gratis’ and the controversy over open licensing you can read more in ‘Is OER actually open? Gratis vs libre’.

Sharing

In these cases, increasing access to resources through sharing, particularly when material is shared digitally, often means that resources are able to go beyond the original contexts and boundaries intended by their creator.

In Section 1.6 you will find some examples and further reading for each of the above characteristics associated with 'openness’.

Activity 1A

The course will explore the meaning of ‘open’ educational resources and ‘open’ educational practices. To begin with, however, let’s focus more broadly on what kind of qualities might be associated with openness.

- Do the above characteristics (sharing, free, transparency and access) resonate with you? Which of these do you feel are particularly relevant in your context and why?

- How would you characterise openness?

Write down your thoughts in your reflective log. You may find it useful to revisit these observations later in the course.

1.3 Open educational resources and open educational practices?

Having thought a bit more about what ‘open’ means, let's now take a closer look at what is meant by practices and resources that are ‘open’. To start with, let’s focus on a particular kind of resource that will help us make sense of openness in practice: open educational resources (OER).

Educational resources are anything you use to help with your teaching or learning. A video you’ve used in class, a lesson plan, a register, a presentation, a textbook or chapter from a book or a model that you use to illustrate an example … the list is endless!

You might have looked for resources online or in the library to accompany your lessons or a presentation. You might have used an online video or found an image which helps illustrate a point you want to make. Maybe you have searched TES Resources or BBC Bitesize for inspiration when planning your lessons. Often there are copyright restrictions on how you can use resources that you find, but within an educational context you are able to use these due to what is described as ‘fair dealing’ or ‘fair use’.

What makes an educational resource open?

An open educational resource (OER) is a resource that, because of the licence it has, gives you explicit information and permission to reuse the resource without needing to ask the content’s author. The permissions given via an open licence state how you can reuse the resource (e.g. whether the author just needs to be attributed, whether you cannot use it for commercial purposes or whether you can make changes to the material) and how you should attribute it. OER are not necessarily always digital, but those that are made available online, for example via repositories, also give users the ability to remix the resources in situ.

From an author’s perspective, releasing your material as an OER and not requiring potential users to seek your permission for reuse can lead to interesting outcomes. You can find out more about ‘what happened next’ in relation to a variety of OER in Alan Levine’s True Stories of Open Sharing.

However, let's first explore in a little more depth what is meant by an OER. Defining OER is important, as what is meant by ‘open’ within this context provides a good foundation for thinking about the things that you need to do when creating an OER and how this might change your own practice.

UNESCO defines Open Educational Resources as:

‘… any type of educational materials that are in the public domain or introduced with an open licence. The nature of these open materials means that anyone can legally and freely copy, use, adapt and re-share them. OER range from textbooks to curricula, syllabi, lecture notes, assignments, tests, projects, audio, video and animation.’

Another way of thinking about what makes an educational resource ‘open’ is to think about what an ‘open’ resource enables you to do with its content/material. David Wiley, a well-known open education advocate describes OER as enabling you to do five things with material: Retain, Reuse, Revise, Remix, and Redistribute. These are also known as the ‘5 Rs’. According to Wiley, facilitating all of the ‘Rs’ enables an educational resource to be described as ‘open’. There are certain considerations that need to be taken into account to make this happen, and these are discussed in more detail later on in the course.

As you can see, just like copyrighted educational resources, OER can be all kinds of different materials you might use in your teaching or learning. OER can be both online and offline and in all kind of formats: many YouTube videos, presentations on Slideshare or photos on Flickr are often openly licensed, whilst whole textbooks in a range of subjects are often openly available (these are called ‘open textbooks’).

Open education

The idea of ‘opening up’, or giving greater access to educational opportunities, is not a new one. Removing barriers to knowledge and increasing access (the process of ‘democratising knowledge’) can be traced back to the development of the printing press, for example prior to compulsory education being introduced in the late 19th Century (1880 in England and Wales and 1872 in Scotland), philanthropic and charitable endeavours provided educational opportunities to working class children in the form of Ragged Schools and other initiatives.

The term ‘OER’ came into common usage in the early 2000s and has received support from many different individuals and organisations. Read about the types of commitments made by different organisations and individuals in the Cape Town Open Education Declaration from 2007 and the 2012 Paris OER Declaration. The Scottish Open Education Declaration of 2013 broadened the scope of the Paris OER Declaration by focusing on education as a whole.

You might be familiar with the open source movement, which was a forerunner of the OER movement. Open source means that code, software and tools are openly available so that people can improve and build on others’ work, as well as access the tools and software for no cost at the point of use. Examples include Moodle, Drupal, Ubuntu and Linux.

This ethos of community, sharing, increased access and collaboration underpins the open education movement and can be described as an ‘open educational practice’.

What does it mean for an educational practice be ‘open’?

As a range of different practices could be described as ‘open’ and support the use of OER, there is no definitive definition of open educational practices (OEP). However, looking closer at two working definitions of OEP will assist in understanding the difference between OER (open resources of a particular type) and OEP (which is more focused on the context and action to engender the use of OER and the outcomes from doing so).

Building on Conole’s (2010) definition of OEP as ‘…the set of activities and support around the creation, use and repurposing of Open Educational Resources’ and the associated ‘contextual’ dimensions of this, Ehlers and Conole (2010) developed a definition of OEP to reflect both the collaborative aspects of open practice and the reasons why all kinds of people might use OER:

‘Open Educational Practices (OEP) are the use of open educational resources with the aim to improve the quality of educational processes and innovate educational environments.’

Other definitions of OEP are broader and emphasise the social justice elements of openness. For example, the working definition used by the Opening Educational Practices in Scotland project:

We think of Open Educational Practices as those educational practices that are concerned with and promote equity and openness. Our understanding of ‘open’ builds on the freedoms associated with ‘the 5 Rs’ of OER, promoting a broader sense of open, emphasising social justice, and developing practices that open up opportunities for those distanced from education.

Open education as ‘disruptive’?

Discussion on the rapid ascendency Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) such as Coursera, edX and FutureLearn over the past few years has often been framed within the context of their potential impact on formal education and the narrative of disruption. The idea of ‘disruptive innovation’ originates from Bower and Christensen (1995), and you can read more about this in relation to MOOCs and open education in the JISC CETIS publication MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher Education. Christensen, Raynor and McDonald (2015) revisit and clarify the idea of disruption in ‘What is disruptive innovation?’.

In responding to such claims about the impact of MOOCs there has also been discussion about how ‘open’ such resources are and determining what the difference is between OER and MOOCs. In answer to the latter question, an OER can, for example, refer to any type of open resource, not just a course. However the ‘openness’ of MOOCs in particular is often in question and MOOCs are often perceived as having a slightly different conception of ‘openness’ than that exemplified by Wiley’s ‘5Rs’. For example, whilst being free to take course or access a resource, you might only be able to view the materials if you sign up. Often MOOC content is not openly licensed, so you won’t be able to remix or reuse the materials used to make up the course.

Similarly, material might only be available for a limited time between the start and end dates of the MOOC and may not be released as OER afterwards. MOOCs are often acknowledged as being ‘open enrolment’ but they may not necessarily be open in terms of their content. However, there are exceptions, for example the Open University’s FutureLearn MOOCs are released on OpenLearn after their final presentation as perpetually open courses (see for example Introduction to cyber security).

Activity 1B

Before moving on to look at open licences and openness in a little more detail, let’s take a few minutes to explore some explanations of what open educational resources are and why open matters. There are a selection of descriptions and videos to choose from in Section 1.6, but to get started watch the short video ‘The OERs – open educational resources’ – you can watch it below or open it in a new window or tab in your web browser.

Transcript

For the longest time human societies evolved very slowly but since not so long ago our pace of change has been increasing exponentially, ever faster and faster and faster and faster and faster and a lot faster. This constant evolution is only possible through the production and assimilation of knowledge and a system transmitting it from generation to generation.

The most efficient system we have come up with so far is formal education a process whose pinnacle of achievement is a degree from a top university. The education given at these institutions opens a huge window of opportunities as students learn from the highest qualified professors and acquire the most cutting edge knowledge available. But the system as it is cannot deliver this knowledge to everyone, it is by nature exclusive. Now imagine that this were to change, how would our world be if everyone could benefit from the opportunities offered by studying at these institutions?

Well this is already happening. Some of the best universities in the US are openly sharing their courses online and this is just part of a trend, the trend of open educational resources. OERs are revolutionary technologies of knowledge delivery that use the internet to share and spread educational content making high quality education available for each motivated person to access for free. Opening access to top university courses is just one of the many things OERs can do. They can also serve as the best high school tutor guiding you through thousands of topics with interactive exercises. They make up what may be the biggest textbook library in the world and provide the best tailored way to improve and broaden your professional skills at your own pace. OERs are creating a new system of education, one which is better adapted to respond to our highly dynamic economy. Equal access to knowledge means equal opportunities in life and in a world with equal opportunities it all depends on you. Now that's the meaning of freedom.

Now use your reflective log to write down your thoughts about your own context and what kinds of resources could be open. Why might it be important to have educational resources that are open?

1.4 The practice of open educational resources

The next sections of the course will explore open practice as ‘use’ and situate the discussion within the context of finding and reusing open educational resources (OER). However, it is first worth remembering that in order to be able to ‘use’ an OER someone first needs to have shared the material and openly licensed it. Indeed, without sharing something with others it is not possible to widen access to that resource, meaningless to choose to make something free or low cost and impossible to increase transparency, as the material is not accessible. Sharing is therefore an important fundamental enabler or characteristic of ‘openness’ (see Section 1.2).

The cycle of creating, reusing or re-versioning material and then sharing it back is sometimes referred to as a ‘virtuous circle’ (see ‘Sharing and reuse in OER: experiences gained from open reusable learning objects in health’). Research has shown that, although a large number of students and educators use or adapt OER, they do not necessarily share the resources they have created on an open licence, nor share back reworked versions of resources they have found (see OER Evidence Report 2013–2014). This course looks at finding and reusing OER in Section 3 and what you need to do to effectively share material in Section 4.

Activity 1C

Reflect on the following questions:

- What kind of resources, if any, do you share?

- Who do you share with?

- Do you know what happens to what you share?

- Do others share with you and if so, is this an important source of finding new resources?

Write down your responses in your reflective log.

Discussion

You might already share materials you have created with colleagues or friends or discuss your ideas informally. In most cases, you probably don’t mind how the materials are reused, as you are familiar with the context and reasons people might be reusing the materials you share. For example, perhaps one of your lesson plans provides a great starting point for a new colleague to develop a plan for their own class. Or a colleague could reuse an activity you developed with clients in a workshop.

However, although you might not mind how others use the resources you share, how do you know it’s OK to reuse resources? This is where an open licence has an important role, as it includes clear instructions to a potential user of a resource about who created it and how it can be used. Even if you don’t mind how someone uses material you have created, it is important to consider others and enable ease of use.

Now let’s take a look at what enables open practice to take place within the context of OER: open licences.

1.5 Open licensing

As noted in Section 1.3, UNESCO defines OER as ‘… any type of educational materials that are in the public domain or introduced with an open licence…’. Open licences tell the user who made the material and give clear instructions as to how, and in what context, the creator would like the material reused (making reuse ‘legal’). OER are also made available at no cost to the end user.

There are different types of open licence, but the most common types used for a range of resources are those produced under a Creative Commons (CC) licence. According to Creative Commons, during 2015 over one billion items will have been given Creative Commons licences!

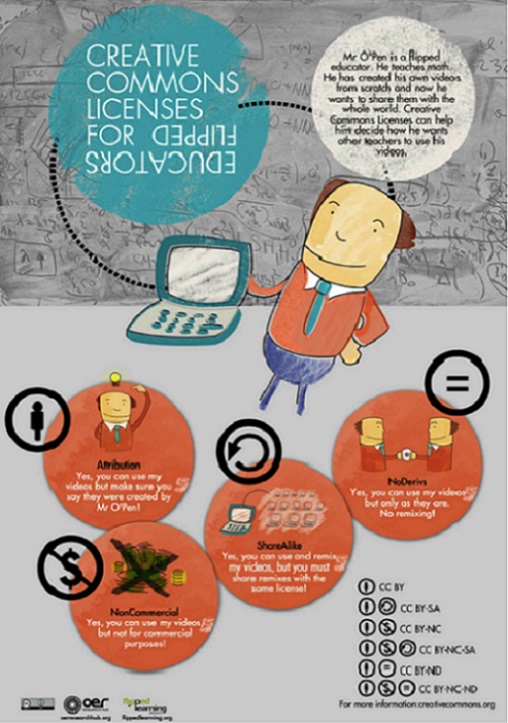

Let’s now take a closer look at the different possible components of a Creative Commons licence and what they mean (Figure 1.5).

As you can see in the bottom right-hand corner of the infographic above, the different components of licences can be combined in different ways to create specific licences with different types of instruction or permissions regarding their reuse (so, for example, the licence CC-BY-NC means that you can reuse the resource in any way you like if you attribute the author and do not reuse it for commercial purposes). Visit Creative Commons to read more about what the different licence types mean for your practice.

Section 4.4 looks in more depth at what licence you should choose when you’re creating an OER and Section 3.4 looks at how to attribute a licence correctly.

Activity 1D

Now that you have been introduced to Creative Commons licences what are your initial impressions of the different licence components?

Can you think of situations where you might use openly licensed materials in your role as a teacher, facilitator or organiser of learning opportunities? Would one kind of licence combination be more appropriate than another?

Write down your thoughts in your reflective log.

Now try the Section 1 quiz to consolidate your knowledge and understanding from this section. Completing the quizzes is part of gaining the statement of participation and/or the digital badge, as explained in Course and badge information.

1.6 If you want to know more ...

Each If you want to know more … section of the course thematically presents additional material and resources on the topics included in that section of the course.

Understanding open practices and open educational resources

Explore different perspectives on openness in this playlist created by the OER Research Hub or take a look at the ‘Understanding OER in 10 videos’ playlist.

For a more detailed and systematic exploration of ‘openness’ Chapter Two, ‘What sort of open?’ of Martin Weller’s book The Battle for Open is highly recommended. You can download the book for free.

Access

For an in-depth review of the open access movement, its motivations and impact, read this post from opensource.com. The article also highlights a 2012 book about open access by long-time advocate Peter Suber, and you can download a copy and find out more on the MIT press website. See also Peter Suber’s more recent reflections from 2013 in ‘Peter Suber on the state of open access: where are we, what still needs to be done?’

Read through the section on open access publishing and the selected resources in P2PU’s Open Research course or the Public Library of Science (PLOS) on open access. The Jisc is in the process of developing best practice advice for open access. Read ‘Unpicking the open access lock’ for suggestions focused on the HE sector. Creative Commons collates different examples of the impact of open licensing. See in particular examples of social justice.

Transparency

Since 2011, the Open Government Partnership has co-ordinated the international effort to help ‘governments [be] more open, accountable and responsive to citizens’. As of April 2016, there were 69 members of the partnership, including the United Kingdom.

Since 2005, UK Research Councils have required recipients of funding to publish open access, stating that ‘Free and open access to the outputs of publicly funded research offers significant social and economic benefits as well as aiding the development of new research.’

In some countries, greater transparency has had a massive impact on reducing corruption (see ‘Why conduct research in the open?’). This has also helped in disaster situations, see ‘How open map data is helping save lives in Nepal’.

Free

Open textbooks are the type of OER that have gained most traction in the United States due to the high cost of proprietary materials and the potential cost savings for students. Read more about the impact these are having across the USA in this opensource.com blog post: ‘How does your state use open educational resources?’.

In October 2015 it was announced that the Affordable College Textbook Act had been reintroduced for consideration by the United States Congress.

Sharing

Katy Jordan blogged the results of her research on MOOC completion rates. Find out what happened next.

The OER Research Hub is an open research project examining the impact of OER on learning and teaching that shared its methodologies, data and tools in the open. This has enabled others, such as the ROER4D project, which investigates the impact of OER in the Global South, to review and reuse their approach (see ‘Question harmonisation process’); and other researchers to reuse their data (see Robert Schwer’s post ‘Data reports OER research hub’).

Open education

For a quick overview of open education and its benefits, read this overview from the Scholarly Publishing & Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC). You can also see how open education developed on the Open Knowledge Foundation’s (OKF’s) crowdsourced timeline of important events. The OKF has also produced the Open Education Handbook, an invaluable resource that covers many of the topics contained in this course.

For a comprehensive look at recent developments in open education, read John Casey’s article ‘Taking care of business? The political economy of MOOCs and open education. If you’re interested in finding out more about the history of The Open University (UK), browse the History of the OU project blog.

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs)

An opensource.com article charts MOOCs, and their development from being openly licensed and open enrolment to being increasingly non-open in terms of course material.

Another exploration of this dual meaning of ‘open’ comes from Timothy Vollmer on the Creative Commons blog.

Using open educational resources (OER)

The Right to Research Coalition produced a series of ‘Open Access 101’ webcasts for conference participants to introduce people to the concepts of open access, open data and open education. Watch them here.

OER Policy for Europe has produced an OER Mythbusting! resource which helps answer common questions about OER and addresses some of the misconceptions about this type of resource. University College London’s (UCL’s) Why Use OER? also provides a more HE-orientated list of reasons to use OER. You could also look at Commonwealth of Learning’s ‘A basic guide to open educational resources (OER)’ or explore different definitions of OER in this Creative Commons wiki entry: ‘What is OER?’

A number of courses on using and reusing OER are available. These include Commonwealth of Learning’s short course called Understanding Open Educational Resources, the ExplOERer project’s facilitated course Learning to (Re)Use Open Educational Resources and Open Washington’s How to use Open Educational Resources.

Explore the relations between different facets of open knowledge by reading the Open Education Working Group’s Open Data as Open Educational Resources: Case Studies of Emerging Practice (eds. Javiera Atenas and Leo Havermann) or take a closer look at the development of open knowledge by exploring this joint Open Knowledge Foundation and Finnish Institute in London crowdsourced map.

Delve deeper into issues around the term ‘open’ within the context of OER by reading Vivien Rolfe’s blog post for ALT: ‘OER: a languishing teenager?’. Review JISC’s ‘Case studies of OER use’ in Higher Education or read the UKOER/SCORE Review Report – Journeys to Open Educational Practice.

Open licensing

For a concise introduction to Creative Commons licences read Jane Park’s overview: ‘What is Creative Commons and why does it matter?’ or watch Paul Stacey present an overview of Creative Commons licences (recorded as part of the BC campus course Adopting Open Textbooks).

If you’re interested in how to look for images that will meet the filter requirements of school PCs, or in devising activities with colleagues to encourage children to explore Creative Commons licensing, find out more in Open Knowledge Foundation’s post by educator Jo Badge.

The DigiLit Leicester project, in partnership with Leicester City Council, has produced a series of resources, including Understanding Open Licensing. Find out more about the project and the project’s other resources.

If you’d like to find out more about how to utilise open licences, check out examples of Creative Commons licence use.

Now go to Section 2 of the course.