Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 7 March 2026, 12:15 AM

Communicable Diseases Module: 1. Basic Concepts in the Transmission of Communicable Diseases

Study Session 1 Basic Concepts in the Transmission of Communicable Diseases

Introduction

As you will recall from the Module on Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation, health is defined as a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being and not the mere absence of disease. The term disease refers to a disturbance in the normal functioning of the body and is used interchangeably with ‘illness’. Diseases may be classified as communicable or non-communicable. Communicable diseases are caused by infectious agents that can be transmitted to other people from an infected person, animal or a source in the environment. Communicable diseases constitute the leading cause of health problems in Ethiopia.

Before we describe each communicable disease relevant to Ethiopia in detail in later study sessions, it is important that you first learn about the basic concepts underlying communicable diseases. Understanding these basic concepts will help you a lot, as they form the basis for this Module.

In this first study session, we introduce you to definitions of important terms used in communicable diseases, the types of infectious agents that cause these diseases, the main factors involved in their transmission, and the stages in their natural development. This will help you to understand how measures for the prevention and control of communicable diseases are put into place at several levels of the health system, including in homes and at your Health Post – which is the focus of Study Session 2.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 1

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

1.1 Define and use correctly all of the key terms printed in bold. (SAQs 1.1 and 1.5)

1.2 Identify the main types of infectious agents. (SAQs 1.2 and 1.3)

1.3 Describe the main reservoirs of infectious agents. (SAQ 1.3)

1.4 Describe the chain of transmission of communicable diseases and explain how infectious agents are transmitted by direct and indirect modes. (SAQs 1.3 and 1.5)

1.5 Describe the characteristics of susceptible hosts and the main risk factors for development of communicable diseases. (SAQ 1.4)

1.6 Describe the stages in the natural history of communicable diseases. (SAQ 1.5)

1.1 What are communicable diseases?

As described in the introduction, the organisms that cause communicable diseases are called infectious agents, and their transmission to new uninfected people is what causes communicable diseases; (note that infectious diseases is an interchangeable term). Familiar examples of communicable diseases are malaria and tuberculosis. Diseases such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes mellitus, which are not caused by infectious agents and are not transmitted between people, are called non-communicable diseases.

This curriculum includes a Module on Non-Communicable Diseases, Emergency Care and Mental Health.

Tuberculosis is caused by an organism called Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which can be transmitted from one person to another. Is TB a communicable or non-communicable disease?

It is a communicable disease because it is caused by an infectious agent and it develops as a result of transmission of the infectious agent.

1.1.1 The burden of communicable diseases in Ethiopia

Outpatient refers to someone who comes to a health facility seeking treatment, but does not stay overnight. An inpatient is someone admitted to a health facility, who has at least one overnight stay.

Communicable diseases are the main cause of health problems in Ethiopia. According to the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health, communicable diseases accounted for most of the top ten causes of illness and death in 2008/09. As you can see in Table 1.1, most causes of outpatient visits are due to communicable diseases.

Can you identify the communicable diseases in Table 1.1?

You may not recognise them all (you will learn about them in later study sessions), but you probably mentioned malaria, respiratory infections, parasitic diseases, pneumonia and diarrhoea.

| Rank | Diagnosis | Percentage of all outpatient visits |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Malaria (clinical diagnosis without laboratory confirmation) | 8.3 |

| 2 | Acute upper respiratory infections | 8.1 |

| 3 | Dyspepsia (indigestion) | 5.9 |

| 4 | Other or unspecified infectious and parasitic diseases | 5.0 |

| 5 | Pneumonia | 4.8 |

| 6 | Other or unspecified diseases of the respiratory system | 4.0 |

| 7 | Malaria (confirmed with species other than Plasmodium falciparum) | 3.7 |

| 8 | Diarrhoea with blood (dysentery) | 3.7 |

| 9 | Helminthiasis (caused by worms) | 3.5 |

| 10 | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (muscles, bones and joints) | 3.0 |

| Total % of all causes of outpatient visits | 47.2 | |

A clinical diagnosis is based on the typical signs and symptoms of the disease, without confirmation from diagnostic tests, e.g. in a laboratory.

The naming of infectious agents is discussed in Section 1.2.1.

Table 1.2 shows that most causes of inpatient deaths are due to communicable diseases, including pneumonia, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and malaria. These and other communicable diseases will be discussed in detail in later study sessions of this module.

| Rank | Diagnosis | Percentage of all inpatient deaths |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pneumonia | 12.4 |

| 2 | Other or unspecified effects of external causes | 7.1 |

| 3 | Tuberculosis | 7.0 |

| 4 | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease | 5.1 |

| 5 | Anaemias | 3.9 |

| 6 | Other or unspecified diseases of the circulatory system (heart, blood vessels) | 3.7 |

| 7 | Hypertension (high blood pressure) and related diseases | 3.5 |

| 8 | Malaria (clinical diagnosis without laboratory confirmation) | 3.1 |

| 9 | Malaria (confirmed with Plasmodium falciparum) | 2.5 |

| 10 | Road traffic injuries | 2.3 |

| Total % of all causes of inpatient deaths | 50.8 | |

1.1.2 Endemic and epidemic diseases

Not all communicable diseases affect a particular group of people, such as a local community, a region, a country or indeed the whole world, in the same way over a period of time. Some communicable diseases persist in a community at a relatively constant level for a very long time and the number of individuals affected remains approximately the same. These communicable diseases are known as endemic to that particular group of people; for example, tuberculosis is endemic in the population of Ethiopia and many other African countries.

A case refers to an individual who has a particular disease.

By contrast, the numbers affected by some communicable diseases can undergo a sudden increase over a few days or weeks, or the rise may continue for months or years. When a communicable disease affects a community in this way, it is referred to as an epidemic. Malaria is endemic in some areas of Ethiopia, and it also occurs as epidemics due to an increase in the number of cases suddenly at the beginning or end of the wet season.

1.1.3 Prevention and control measures

The health problems due to communicable diseases can be tackled by the application of relatively easy measures at different levels of the health system. Here, we will use some examples at the individual and community levels, which are relevant to your work as a Health Extension Practitioner.

Some measures can be applied before the occurrence of a communicable disease to protect a community from getting it, and to reduce the number of cases locally in the future. These are called prevention measures. For example, vaccination of children with the measles vaccine is a prevention measure, because the vaccine will protect children from getting measles. Vaccination refers to administration of vaccines to increase resistance of a person against infectious diseases.

Once a communicable disease occurs and is identified in an individual, measures can be applied to reduce the severity of the disease in that person, and to prevent transmission of the infectious agent to other members of the community. These are called control measures. For example, once a child becomes infected with measles, treatment helps reduce the severity of the disease, and possibly prevents the child’s death, but at the same time it decreases the risk of transmission to other children in the community. In this context, treatment of measles is considered a control measure.

Later in this Module, you will learn that the widespread use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs) is recommended as a prevention measure for malaria, which is transmitted to people by mosquitoes. If you promote the effective use of mosquito nets in your community, how would you expect the number of malaria cases to change over time?

An increase in the effective use of mosquito nets should reduce the number of cases of malaria.

Next we look at the main ways in which infectious agents are transmitted.

1.2 Factors involved in the transmission of communicable diseases

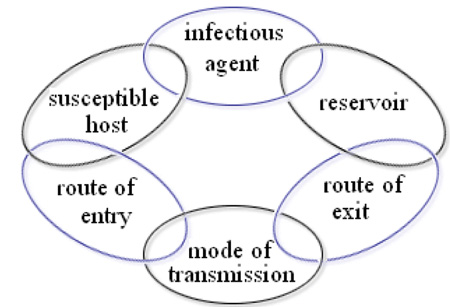

Transmission is a process in which several events happen one after the other in the form of a chain. Hence, this process is known as a chain of transmission (Figure 1.1). Six major factors can be identified: the infectious agent, the reservoir, the route of exit, the mode of transmission, the route of entry and the susceptible host. We will now consider each of these factors in turn.

1.2.1 Infectious agents

Scientific names

Tables 1.1 and 1.2 referred to Plasmodium falciparum as an infectious agent causing malaria. This is an example of how infectious agents are named scientifically, using a combination of two words, the ‘genus’ and the ‘species’ names. The genus name is written with its initial letter capitalised, followed by the species name which is not capitalised. In the example above, Plasmodium is the genus name and falciparum refers to one of the species of this genus found in Ethiopia. There are other species in this genus, which also cause malaria, e.g. Plasmodium vivax.

Sizes and types of infectious agents

Infectious agents can have varying sizes. Some, such as Plasmodium falciparum and all bacteria and viruses, are tiny and are called micro-organisms, because they can only be seen with the aid of microscopes. Others, such as the ascaris worm (Ascaris lumbricoides), can be easily seen with the naked eye. The different types of infectious agents are illustrated in Table 1.3 according to their size, starting with the largest and ending with the smallest, and are then discussed below.

| Type of infectious agent | Number of cells | Visibility | Examples |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Helminths | many | Visible with the naked eye | Ascaris worm causes ascariasis Its length reaches 15–30 cm |  |

Protozoa | 1 | Visible with a standard microscope | Plasmodium falciparum causes malaria |  |

Bacteria | 1 | Visible only with a special microscope; much smaller in size than protozoa | Vibrio cholerae causes cholera |  |

Viruses | 0 | Visible only with a special microscope; much smaller in size than bacteria | HIV causes AIDS |  |

Helminths are worms made up of many cells; for example, Ascaris lumbricoides.

Protozoa are micro-organisms made up of one cell; for example, Plasmodium falciparum.

Bacteria are also micro-organisms made up of one cell, but they are much smaller than protozoa and have a different structure; for example Vibrio cholerae, which causes cholera.

Viruses are infectious agents that do not have the structure of a cell. They are more like tiny boxes or particles and are much smaller than bacteria; for example, HIV (the Human Immunodeficiency Virus), which can lead to AIDS.

Though not as common as causes of communicable disease in humans, other types of infectious agents include fungi (e.g. ringworm is caused by a fungus infection), and mites (similar to insects), which cause scabies.

1.2.2 Reservoirs of infectious agents

Many infectious agents can survive in different organisms, or on non-living objects, or in the environment. Some can only persist and multiply inside human beings, whereas others can survive in other animals, or for example in soil or water. The place where the infectious agent is normally present before infecting a new human is called a reservoir. Without reservoirs, infectious agents could not survive and hence could not be transmitted to other people. Humans and animals which serve as reservoirs for infectious agents are known as infected hosts. Two examples are people infected with HIV and with the bacteria that cause tuberculosis; these infectious agents persist and multiply in the infected hosts and can be directly transmitted to new hosts.

Animals can also be reservoirs for the infectious agents of some communicable diseases. For example, dogs are a reservoir for the virus that causes rabies (Figure 1.3). Diseases such as rabies, where the infectious agents can be transmitted from animal hosts to susceptible humans, are called zoonoses (singular, zoonosis).

Non-living things like water, food and soil can also be reservoirs for infectious agents, but they are called vehicles (not infected hosts) because they are not alive. You will learn more about them later in this study session.

Bacteria called Mycobacterium bovis can be transmitted from cattle to humans in raw milk and cause a type of tuberculosis. In this example, what is the infectious agent and the infected host or hosts?

The infectious agent is Mycobacterium bovis and the infected hosts are cattle and humans.

1.2.3 Route of exit

Before an infectious agent can be transmitted to other people, it must first get out of the infected host. The site on the infected host through which the infectious agent gets out is called the route of exit. Some common examples are described below.

Respiratory tract

The routes of exit from the respiratory tract are the nose and the mouth. Some infectious agents get out of the infected host in droplets expelled during coughing, sneezing, spitting or talking, and then get transmitted to others (Figure 1.4). For example, people with tuberculosis in their lungs usually have a persistent cough; Mycobacterium tuberculosis uses this as its route of exit.

Gastrointestinal tract

The anus is the route of exit from the gastrointestinal tract (or gut). Some infectious agents leave the human body in the stool or faeces (Figure 1.5). For example, the infectious agents of shigellosis, a disease which can cause bloody diarrhoea, use this route of exit.

Skin

Some types of infectious agents can exit the body through breaks in the skin. For example, this route of exit is used by Plasmodium protozoa, which are present in the blood and get out of the human body when a mosquito bites through the skin to suck blood.

1.2.4 Modes of transmission

Once an infectious agent leaves a reservoir, it must get transmitted to a new host if it is to multiply and cause disease. The route by which an infectious agent is transmitted from a reservoir to another host is called the mode of transmission. It is important for you to identify different modes of transmission, because prevention and control measures differ depending on the type. Various direct and indirect modes of transmission are summarised in Table 1.3 and discussed below it.

| Mode of transmission | Sub-types of transmission |

|---|---|

| Direct | Touching Sexual intercourse Biting Direct projection of droplets Across the placenta |

| Indirect | Airborne Vehicle-borne Vector-borne |

Direct modes of transmission

Direct transmission refers to the transfer of an infectious agent from an infected host to a new host, without the need for intermediates such as air, food, water or other animals. Direct modes of transmission can occur in two main ways:

- Person to person: The infectious agent is spread by direct contact between people through touching, biting, kissing, sexual intercourse or direct projection of respiratory droplets into another person’s nose or mouth during coughing, sneezing or talking. A familiar example is the transmission of HIV from an infected person to others through sexual intercourse.

- Transplacental transmission: This refers to the transmission of an infectious agent from a pregnant woman to her fetus through the placenta. An example is mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV.

Indirect modes of transmission

Indirect transmission is when infectious agents are transmitted to new hosts through intermediates such as air, food, water, objects or substances in the environment, or other animals. Indirect transmission has three subtypes:

- Airborne transmission: The infectious agent may be transmitted in dried secretions from the respiratory tract, which can remain suspended in the air for some time. For example, the infectious agent causing tuberculosis can enter a new host through airborne transmission.

- Vehicle-borne transmission: A vehicle is any non-living substance or object that can be contaminated by an infectious agent, which then transmits it to a new host. Contamination refers to the presence of an infectious agent in or on the vehicle.

- Vector-borne transmission: A vector is an organism, usually an arthropod, which transmits an infectious agent to a new host. Arthropods which act as vectors include houseflies, mosquitoes, lice and ticks.

Arthropods are invertebrates (animals without backbones), such as insects, which have segmented bodies and three pairs of jointed legs.

Can you suggest some examples of vehicles that could transmit specific infectious agents indirectly to new hosts?

You may have thought of some of the following:

- Contaminated food, water, milk, or eating and drinking utensils. For example, the infectious agent of cholera can be transmitted to a person who eats food or drinks water contaminated with faeces containing the organism.

- Contaminated objects such as towels, clothes, syringes, needles and other sharp instruments. For example, sharp instruments contaminated with HIV-infected blood can transmit HIV if they penetrate the skin of another person.

- Soil is a vehicle for some bacteria. For example, a person can be infected with bacteria that cause tetanus if contaminated soil gets in through broken skin.

Can you think of a vector-borne disease mentioned several times in this study session?

Malaria is transmitted by mosquito vectors.

1.2.5 Route of entry

Successful transmission of the infectious agent requires it to enter the host through a specific part of the body before it can cause disease. The site through which an infectious agent enters the host is called the route of entry.

We have already mentioned all the routes of entry in previous sections. Can you summarise what they are, and give an example of an infectious agent for each of them?

The routes of entry are:

- The respiratory tract: some infectious agents enter the body in air breathed into the lungs. Example: Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- The gastrointestinal tract: some infectious agents enter through the mouth. Example: the infectious agents causing diarrhoeal diseases enter through the mouth in contaminated food, water or on unclean hands (Figure 1.6).

- The skin provides a natural barrier against entry of many infectious agents, but some can enter through breaks in the skin. Example: malaria parasites (Plasmoduim species) get into the body when an infected mosquito bites through the skin to suck blood.

Can you think of an infectious agent that enters and exits through the same body part? Can you think of one where the entry and exit routes are different parts of the body?

The route of entry and exit for Mycobacterium tuberculosis is through the respiratory system. The route of entry for infectious agents of diarrhoeal diseases is the mouth, but the route of exit is the anus with the faeces.

1.2.6 Susceptible hosts and risk factors

After an infectious agent gets inside the body it has to multiply in order to cause the disease. In some hosts, infection leads to the disease developing, but in others it does not. Individuals who are likely to develop a communicable disease after exposure to the infectious agents are called susceptible hosts. Different individuals are not equally susceptible to infection, for a variety of reasons.

Factors that increase the susceptibility of a host to the development of a communicable disease are called risk factors. Some risk factors arise from outside the individual – for example, poor personal hygiene, or poor control of reservoirs of infection in the environment. Factors such as these increase the exposure of susceptible hosts to infectious agents, which makes the disease more likely to develop.

Additionally, some people in a community are more likely to develop the disease than others, even though they all have the same exposure to infectious agents. This is due to a low level of immunity within the more susceptible individuals. Immunity refers to the resistance of an individual to communicable diseases, because their white blood cells and antibodies (defensive proteins) are able to fight the infectious agents successfully. Low levels of immunity could be due to:

- diseases like HIV/AIDS which suppress immunity

- poorly developed or immature immunity, as in very young children

- not being vaccinated

- poor nutritional status (e.g. malnourished children)

- pregnancy.

In general terms, in what two ways could the risk of developing a communicable disease be reduced?

By reducing exposure to infectious agents, or increasing the person’s immunity, for example by vaccination or improving their diet.

Vaccination is discussed in detail in the Immunization Module in this curriculum.

Finally, look back at Figure 1.2. We can now summarise the chain of transmission as follows:

- the infectious agent gets out of the reservoir through a route of exit

- it gets transmitted to a susceptible host by a direct or indirect mode of transmission and it gets into the susceptible host through a route of entry

- if it multiplies sufficiently in the susceptible host it will cause a communicable disease.

1.3 Natural history of a communicable disease

The natural history of a disease is also referred to as the course of the disease, or its development and progression; these terms can be used interchangeably.

The natural history of a communicable disease refers to the sequence of events that happen one after another, over a period of time, in a person who is not receiving treatment. Recognising these events helps you understand how particular interventions at different stages could prevent or control the disease. (You will learn about this in detail in Study Session 2.)

Events that occur in the natural history of a communicable disease are grouped into four stages: exposure, infection, infectious disease, and outcome (see Figure 1.6). We will briefly discuss each of them in turn.

1.3.1 Stage of exposure

Here a contact refers to an association between a susceptible host and a reservoir of infection, which creates an opportunity for the infectious agents to enter the host.

In the stage of exposure, the susceptible host has come into close contact with the infectious agent, but it has not yet entered the host’s body cells. Examples of an exposed host include:

- a person who shakes hands with someone suffering from a common cold

- a child living in the same room as an adult with tuberculosis

- a person eating contaminated food or drinking contaminated water.

1.3.2 Stage of infection

At this stage the infectious agent has entered the host’s body and has begun multiplying. The entry and multiplication of an infectious agent inside the host is known as the stage of infection. For instance, a person who has eaten food contaminated with Salmonella typhii (the bacteria that cause typhoid fever) is said to be exposed; if the bacteria enter the cells lining the intestines and start multiplying, the person is said to be infected.

At this stage there are no clinical manifestations of the disease, a term referring to the typical symptoms and signs of that illness. Symptoms are the complaints the patient can tell you about (e.g. headache, vomiting, dizziness). Signs are the features that would only be detected by a trained health worker (e.g. high temperature, fast pulse rate, enlargement of organs in the abdomen).

1.3.3 Stage of infectious disease

At this stage the clinical manifestations of the disease are present in the infected host. For example, a person infected with Plasmodium falciparum, who has fever, vomiting and headache, is in the stage of infectious disease – in this case, malaria. The time interval between the onset (start) of infection and the first appearance of clinical manifestations of a disease is called the incubation period. For malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum the incubation period ranges from 7 to 14 days.

Remember that not all infected hosts may develop the disease, and among those who do, the severity of the illness may differ, depending on the level of immunity of the host and the type of infectious agent. Infected hosts who have clinical manifestations of the disease are called active cases. Individuals who are infected, but who do not have clinical manifestations, are called carriers. Carriers and active cases can both transmit the infection to others.

To which stage in the natural history of a communicable disease do a. active cases and b. carriers belong?

- a.Carriers are in the stage of infection, as they do not have clinical manifestations of the disease.

- b.Active cases are in the stage of infectious disease, as they have the manifestations.

Depending on the time course of a disease and how long the clinical manifestations persist, communicable diseases can be classified as acute or chronic. Acute diseases are characterised by rapid onset and short duration of illness. For instance, diarrhoea that starts suddenly and lasts less than 14 days is an acute diarrhoeal disease. Chronic diseases are characterised by prolonged duration of illness; for example, a chronic diarrhoeal disease lasts more than 14 days.

1.3.4 Stage of outcome

At this stage the disease may result in recovery, disability or death of the patient. For example, a child who fully recovers from a diarrhoeal disease, or is paralyzed from poliomyelitis, or dies from malaria, is in the stage of outcome.

In the next study session you will learn how communicable diseases are classified, and about the main types of prevention and control measures.

Summary of Study Session 1

In Study Session 1 you have learned that:

- Communicable diseases are caused by infectious agents that can be transmitted to susceptible individuals from an infected person, or from other animals, objects or the environment.

- Infectious agents include helminths, protozoa, bacteria, viruses and fungi.

- Six factors are involved in the transmission of communicable diseases: the infectious agent, the reservoir, route of exit, mode of transmission, route of entry, and the susceptible host.

- A reservoir is a human, another animal, or a non-living thing (such as soil), where the infectious agent normally lives.

- Modes of transmission of an infectious agent can be directly through person-to-person contact, or across the placenta from mother to fetus. Indirect transmission can occur through air, vehicles such as water, food and contaminated objects, or via a vector such as a mosquito.

- A susceptible host is a person or animal who can develop infection if exposed to the infectious agent. Susceptibility is increased if exposure is high, or the host’s immunity is low.

- The natural history of an untreated communicable disease has four stages: stage of exposure, stage of infection, stage of infectious disease, and stage of outcome.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 1

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the questions below. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 1.1 (tests Learning Outcome 1.1)

Consider a disease known as diabetes mellitus, which is characterised by an increase in the blood sugar level. Infectious agents may contribute to the development of the disease in early childhood, but are not the main cause of the disease. Can it be classified as communicable? Explain your reasons.

Answer

Diabetes mellitus is not communicable; rather it is non-communicable for the following reasons:

- The main cause of the disease is not an infectious agent

- It cannot be transmitted from a person with diabetes mellitus to another person.

SAQ 1.2 (tests Learning Outcome 1.2)

Giardiasis is an endemic communicable disease in Ethiopia. Its infectious agent (Giardia intestinalis) is a single-celled organism bigger than bacteria, but not visible with the naked eye. To which class of infectious agents listed below is it likely to belong? Explain your reasons.

A Helminths

B Viruses

C Protozoa.

Answer

C Protozoa is the correct answer. This group of infectious agents are single-celled organisms, which are bigger than bacteria but not visible with the naked eye.

SAQ 1.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4)

Hookworm infection is caused by parasites which are common in Ethiopia. The parasites live in the human intestine and lay eggs which are expelled from the body with the faeces into the soil. The eggs grow into worms in the soil, which penetrate the skin of people walking barefooted. Identify each of the following in this example:

A The infectious agent

B The reservoir

C The mode of transmission

D The route of exit and the route of entry.

Answer

A The infectious agents are hookworms.

B Humans are the reservoir for this parasite.

C The mode of transmission is indirectly by contaminated soil.

D The route of exit is through the anus with faeces, and the route of entry is through the skin.

SAQ 1.4 (tests Learning Outcome 1.4)

Based on the description in SAQ 1.3, what are the risk factors for hookworm infection?

Answer

The risk factors for hookworm infection include walking barefooted and poor environmental hygiene due to expelling faeces into the soil.

First read Abebe’s story and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case study 1.1 Abebe’s story

Typhoid fever is a disease that manifests clinically with high fever and headache. Suppose Abebe is infected with the infectious agent of typhoid fever, but he has no manifestations of the disease. He works in a cafe and among 20 people he served in one day, five got infected, but only three of these developed the disease. Among the three who developed typhoid fever, two recovered and one died.

SAQ 1.5 (tests Learning Outcomes 1.1, 1.2 and 1.6)

From the given information:

- a.What are the likely modes of transmission?

- b.Which of the affected persons are active cases and which are carriers?

- c.Can you group the 20 people who were served in the cafe into the four stages of the natural history of a communicable disease?

Answer

- a.The likely modes of transmission are contaminated food and water served in the café.

- b.Abebe and two of the five infected persons who did not develop the disease are carriers; whereas the three persons who developed the disease are active cases.

- c.All the 20 people who Abebe served in the cafe were in the stage of exposure. Only five of these persons were infected and hence were in the stage of infection. Among the five infected, the three who developed typhoid fever were in the stage of infectious disease. And among these, the stage of outcome for two was recovery and for one it was death.