Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 7:48 AM

Communicable Diseases Module: 2. Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases and Community Diagnosis

Study Session 2 Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases and Community Diagnosis

Introduction

In the first study session, you learned about the basic concepts in the transmission of communicable diseases. The knowledge you gained will help you to understand this study session because they are interlinked. In the first section, you will learn about the different ways of classifying communicable diseases. Following classification you will learn the approaches in prevention and control of communicable disease. This will help you in identifying appropriate measures for the prevention and control of communicable diseases that you, as a Health Extension Practitioner, and other health workers will put into place in your community. This study session forms the basis for study sessions later in this Module on specific diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Finally, you will learn how to apply the methods of community diagnosis to assess and prioritise actions to prevent and control the main communicable diseases in your community.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 2

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

2.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 2.1, 2.2 and 2.4)

2.2 Identify the two main ways of classifying communicable diseases, and illustrate their usefulness. (SAQs 2.1 and 2.2)

2.3 Describe and give examples of prevention and control measures targeting the reservoir of infection. (SAQs 2.3 and 2.4)

2.4 Describe and give examples of prevention and control measures targeting the mode of transmission of communicable diseases. (SAQs 2.3 and 2.4)

2.5 Describe and give examples of prevention and control measures that protect the susceptible host from communicable diseases. (SAQs 2.3 and 2.4)

2.6 Describe the basic processes involved in community diagnosis and give examples of how you would apply these methods. (SAQ 2.5)

2.1 Classification of communicable diseases

Communicable diseases can be classified in different ways into groups with similar characteristics. Classification will help you to select and apply appropriate prevention and control measures that are common to a class of communicable diseases. In this section you will learn the basis for each way of classifying communicable diseases and its relevance to your practice. This will be clarified using examples of communicable diseases that you may already be familiar with.

In Study Session 1 you have learned the types of infectious agents which can be used for classification of communicable diseases. Apart from this, there are two main ways of classifying communicable diseases, which are important for you to know. The classification can be clinical or epidemiologic, as described in Box 2.1.

Box 2.1 Two ways of classifying communicable diseases

Clinical classification is based on the main clinical manifestations (symptoms and signs) of the disease.

Epidemiologic classification is based on the main mode of transmission of the disease.

Now, we will discuss the details of each type of classification with specific examples.

2.1.1 Clinical classification of communicable diseases

As stated in Box 2.1, this classification is based on the main clinical manifestations of the disease. This way of classification is important in helping you to treat the symptoms and signs that are common to (shared by) individuals who suffer from different diseases. Clinical classification is illustrated by the example given below.

Diarrhoeal diseases

Some diseases are classified as diarrhoeal diseases. The main clinical symptom is diarrhoea, which means passage of loose stool (liquid faeces) three or more times per day. Two examples of diarrhoeal diseases are shigellosis and cholera. (Further details about these diseases are in Study Session 33 of this Module). People with watery diarrhoeal disease suffer from loss of fluid from their bodies. Therefore, even though the infectious agent might be different, as in the examples of shigellosis and cholera, the common management of patients with diarrhoeal disease includes fluid replacement (Figure 2.1).

Other clinical classifications

Another clinical classification refers to diseases characterised as febrile illnesses, because they all have the main symptom of fever, for example, malaria. Respiratory diseases are another clinical classification; their main symptoms include cough and shortness of breath, as in pneumonia.

Diseases have many symptoms and signs. As a Health Extension Practitioner, you will need to decide which symptom is the main one for classification. Using the method of clinical classification will help you decide to treat the main symptom. You will be able to identify the main symptoms more easily when you learn about specific diseases later on in this Module. Bear in mind that for most diseases, treatment of the main symptom is only supportive (that is it will not cure the disease). Therefore, you have to give treatment specific to the infectious agent. This will be discussed later in this Module under the specific diseases.

2.1.2 Epidemiologic classification

This classification is based on the main mode of transmission of the infectious agent. The importance of this classification for you is that it enables you to select prevention and control measures which are common to (shared by) communicable diseases in the same class, so as to interrupt the mode of transmission. To clarify the importance of epidemiologic classification, consider the following examples.

Cholera and typhoid fever are two different diseases which can be transmitted by drinking contaminated water. Therefore, they are classified as waterborne diseases, using the epidemiologic classification. The common prevention measures for the two diseases, despite having different infectious agents, include protecting water sources from contamination and treatment of unsafe water before drinking, for example by boiling (Figure 2.2) or adding chlorine.

The main types of epidemiologic classification are described in Box 2.2.

Box 2.2 Epidemiologic classification of communicable diseases

Based on the mode of transmission of the infectious agent, communicable diseases can be classified as:

- Waterborne diseases: transmitted by ingestion of contaminated water.

- Foodborne diseases: transmitted by the ingestion of contaminated food.

- Airborne diseases: transmitted through the air.

- Vector-borne diseases: transmitted by vectors, such as mosquitoes and flies.

Suppose while you are working in your health facility, a 20 year-old man comes to you complaining of high fever accompanied by violent shivering (rigors), vomiting and headache. A blood examination for malaria found evidence of Plasmodium falciparum. Assume that he acquired the parasite after being bitten by infected mosquitoes. How would you classify this man’s health problem, using two different classifications?

You will learn how to carry out the rapid blood test for malaria in Study Session 7 of this Module.

Clinically the disease is classed as a febrile illness because fever was the main clinical manifestation. Using epidemiologic classification, the disease is classed as vector-borne because it was transmitted by the mosquito.

When you have studied more about malaria in later study sessions, you will be able to see how the clinical classification as a febrile illness can help you in the management of the patient. As he has a high fever, in addition to treatment with anti-malarial drugs, you should take measures to lower the fever by giving him paracetamol. The epidemiologic classification of the disease as vector-borne helps you to select measures to prevent and control malaria in the community, for example by advocating protection from mosquito bites by using bed nets, and drainage of small collections of water where mosquitoes breed.

In the next section we will discuss the general approaches to prevention and control of communicable diseases at community level.

2.2 General approaches in the prevention and control of communicable diseases

You now have a working knowledge of factors involved in the chain of disease transmission (described in Study Session 1), and how to classify communicable diseases. This knowledge will help you to identify prevention and control measures that can be applied at each link in the chain. When we say prevention it refers to measures that are applied to prevent the occurrence of a disease. When we say control it refers to measures that are applied to prevent transmission after the disease has occurred. Most of the measures for prevention and control of communicable diseases are relatively easy and can be applied using the community’s own resources. You have an important role in educating the public to apply these measures effectively.

You have learned that prevention and control of communicable diseases involves interventions to break the chain of transmission. Can you recall the six factors involved in the chain?

They are the infectious agent, the reservoir, the route of exit, the mode of transmission, the route of entry, and the susceptible host.

We can simplify the discussion of prevention and control measures acting on the chain of transmission by merging these six factors into three groups:

- Infectious agents in the reservoir of infection and the route of exit from the reservoir are discussed under the heading ‘reservoir’.

- The ‘mode of transmission’ is the second category that we will discuss.

- The route of entry and the susceptible host are discussed under the heading ‘susceptible host’.

2.2.1 Measures targeting the reservoir of infection

During your community practice, the prevention and control measures you will undertake depend on the type of reservoir. In this section we will discuss measures for tackling human and animal reservoirs. When you encounter an infected person, you should undertake the measures described below.

Diagnosis and treatment

First, you should be able to diagnose and treat cases of the disease, or refer the patient for treatment at a higher health facility. There are two ways to identify an infected individual: when a patient comes to you (Box 2.3, on the next page, describes how you should approach a patient in order to identify a case), and by screening (discussed below). Identifying and treating cases as early as possible, reduces the severity of the disease for the patient, avoiding progression to complications, disability and death; and it also reduces the risk of transmission to others.

Box 2.3 Approaches to the diagnosis of a case

- The first step is to ask about the main complaints of the patient.

- Then ask about the presence of other related symptoms and risk factors.

- Examine the patient physically to detect signs of any diseases you suspect.

- Finally, refer the patient for laboratory examinations if available (e.g. blood examination for malaria).

Screening

Issues related to HIV/AIDS will be further discussed in Study Sessions 20–30 later in this Module.

Screening refers to the detection of an infection in an individual who does not show any signs or symptoms of the disease. It is carried out using specific tests called screening tests. Screening will help you to detect an infection early and organise appropriate treatment so as to reduce complications and prevent transmission to others. An example of screening that may be familiar to you is screening the blood of pregnant women for HIV infection.

Isolation

You will learn further details about tuberculosis in Study Sessions 13–17 of this Module.

Following detection of an infectious disease, you may need to separate patients from others to prevent transmission to healthy people. This is called isolation. It is not indicated for every infection, but it is important to isolate people with highly severe and easily transmitted diseases. For example, an adult case of active pulmonary tuberculosis (‘pulmonary’ means in the lungs) should be kept in isolation in the first two weeks of the intensive phase of treatment. The isolation period lasts until the risk of transmission from the infected person has reduced or stopped. The period and degree of isolation differs between different diseases, as you will learn in later study sessions.

Reporting

How to report communicable diseases will be discussed in Study Session 41 of this Module.

Cases of communicable diseases should be reported to a nearby health centre or woreda Health Office periodically, using the national surveillance guidelines.

Animal reservoirs

When infected animals are the reservoir involved in the transmission of communicable diseases, different measures can be undertaken against them. The type of action depends on the animal reservoir, and ranges from treatment to destroying the infected animal, depending on the usefulness of the animal and the availability of treatment. For example to prevent and control a rabies outbreak, the measures to be taken are usually to destroy all stray dogs in the area, and vaccinate pet dogs if the owner can afford this protection and the vaccine is available.

2.2.2 Measures targeting the mode of transmission

The measures that can be applied to interrupt transmission of infectious agents in water, food, other vehicles and by vectors, are described below.

The detailed discussion of interventions to prevent and control all these modes of transmission can be found in the Hygiene and Environmental Health Module.

Water

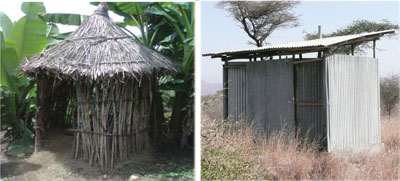

Measures to prevent transmission of infection due to contaminated water include boiling the water, or adding chemicals like chlorine. Disinfection is the procedure of killing most, but not all, infectious agents outside the body by direct exposure to chemicals. Adding chlorine is one method of disinfecting water. Physical agents can also be used, for example filtering water through a box of sand, or pouring it through several layers of fine cloth. Faecal contamination of water should also be prevented by protecting water sources and through proper use of latrines (Figure 2.3).

Food

Measures to prevent transmission in contaminated food include washing raw vegetables and fruits, boiling milk, and cooking meat and other food items thoroughly before eating. Contamination with faeces can be prevented by hand washing and proper use of latrines.

Other vehicles

Measures to tackle transmission in or on vehicles other than water and food include:

- Contaminated objects like household utensils for cooking, eating and drinking should be washed with soap and water.

- Contaminated medical instruments and clothing can be sterilised, disinfected or properly disposed of.

Sterilisation involves destruction of all forms of micro-organisms by physical heat, irradiation, gas or chemical treatment. The difference between disinfection and sterilisation is that disinfection kills most, but not all, micro-organisms. Disinfection can be done using alcohol, chlorine, iodine or heating at the domestic level; whereas sterilisation has to use extreme heating, irradiation or strong chemicals like a high concentration of chlorine.

Vectors

Measures against vectors include preventing breeding of vectors, through proper disposal of faeces and other wastes, eradication of breeding sites, and disinfestation. Disinfestation is the procedure of destroying or removing small animal pests, particularly arthropods and rodents, present upon the person, the clothing, or in the environment of an individual, or on domestic animals. Disinfestation is usually achieved by using chemical or physical agents, e.g. spraying insecticides to destroy mosquitoes, and removing lice from the body and clothing.

2.2.3 Measures targeting the susceptible host

The measures described below help to protect the susceptible host either from becoming infected, or from developing the stage of infectious disease if they are exposed to the infectious agents.

Vaccination

You will learn more about vaccine-preventable diseases in Study Sessions 3 and 4 of this Module.

As you already know from Study Session 1, vaccination refers to administration of vaccines to increase the resistance of the susceptible host against specific vaccine-preventable infections. For example, measles vaccination helps to protect the child from measles infection, and BCG vaccination gives some protection from tuberculosis (Figure 2.4).

Chemoprophylaxis

Chemoprophylaxis is pronounced ‘keem-oh-proff-ill-axe-sis’; (‘chemo’ refers to medical drugs, and ‘prophylaxis’ means ‘an action taken to prevent a disease’).

Chemoprophylaxis refers to the drugs given to exposed and susceptible hosts to prevent them from developing an infection. For example, individuals from non-malarial areas who are going to a malaria endemic area can take a prophylactic drug to prevent them from developing the disease if they become infected with malaria parasites from a mosquito bite.

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle

Proper nutrition and exercise improves a person’s health status, supports the effective functioning of their immune system, and increases resistance to infection.

Limiting exposure to reservoirs of infection

Measures taken to decrease contact with reservoirs of infection include:

- Condom use to prevent transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- Use of insecticide treated nets (ITNs) over the bed at night, insect repellants and wearing protective clothing to prevent diseases transmitted by insect vectors.

- Wearing surgical or very clean gloves and clean protective clothing while examining patients, particularly if they have wounds, or the examination involves the genital area.

- Keeping personal hygiene, like taking a daily bath and washing your hands frequently. Hand washing with soap and water is the simplest and one of the most effective ways to prevent transmission of many communicable diseases (Figure 2.5). The times when hands must be washed are indicated in Box 2.4.

Box 2.4 When to wash hands with soap and clean water?

- After using the toilet

- After handling animals or animal waste

- After changing a diaper (nappy) or cleaning a child’s bottom

- Before and after preparing food

- Before eating

- After blowing the nose, coughing, or sneezing

- Before and after caring for a sick person

- After handling waste material.

Now you have many good ideas on what measures can be undertaken to prevent and control communicable diseases. However, you have to apply these methods effectively in order to prevent and control the most important communicable diseases in your community. But how do you identify these diseases? In the next section we will answer this question.

2.3 Community diagnosis

In order to select and apply effective prevention and control measures, you first have to determine which type of diseases are common in the community you are working with. How do you do that? The method is called community diagnosis and it involves the following four steps:

Data collection methods and data analysis are described in the Module on Health Management, Ethics and Research.

- Data collection

- Data analysis

- Prioritising problems

- Developing an action plan.

Let’s start with data collection and proceed to the others step by step.

2.3.1 Data collection

Data collection refers to gathering data about the health problems present in the community. This is important as it will help you to have good ideas about the type of problems present in the area where you work. Where do you get useful data concerning the health problems in your community? The following sources of data can be used:

- Discussion with community members about their main health problems

- Reviewing records of the health services utilised by the community

- Undertaking a community survey or a small-scale project

- Observing the risks to health present in the community.

After collecting data it should be analysed to make meaning out of it.

2.3.2 Data analysis

Data analysis refers to categorising the whole of the data you collected into groups so as to make meaning out of it. For instance you can assess the magnitude of a disease by calculating its prevalence and its incidence from the numbers of cases you recorded and the number of people in the population in your community.

Prevalence rates and incidence rates can also be expressed as ‘per 10,000’ or ‘per 100,000’ in much larger populations, e.g. of a region or a whole country.

Prevalence refers to the total number of cases existing in the population at a point in time, or during a given period (e.g. a particular month or year). The number of cases can be more usefully analysed by calculating the prevalence rate in the community: to do this you divide the total number of cases you recorded in a given period into the total number of people in the population. The result is expressed ‘per 1,000 population’ in a community as small as a kebele. For example, suppose that in one year you record 100 cases of malaria in a kebele of 5,000 people: for every 1,000 people in the kebele, there were 20 malaria cases in that year. So the prevalence rate of malaria in that kebele is expressed as 20 cases per 1,000 people in that year.

Calculating the prevalence rate is more useful than just counting the number of cases, because the population size in your kebele can change over time. The prevalence rate takes account of changes in the number of people, so you can compare the prevalence rates from different years, or compare the rate in your kebele with the rate in another one.

Incidence refers only to the number of new cases of a disease occurring in a given period. The incidence rate is calculated by dividing the total number of new cases of the disease in a certain period of time into the total number of people in the population, and is expressed as ‘per 1,000 population’.

If there were 10 new cases of cholera in a kebele of 5,000 people in one month, what is the incidence rate of cholera per 1,000 population in that period?

The incidence rate in this example is two new cholera cases per 1,000 population.

As a health professional working in a community affected by several health problems at the same time it is difficult to address all the problems at once. Therefore, you should give priority to the most important ones first. But how do you prioritise? You are going to see how to do that next.

2.3.3 Prioritising health problems

Prioritising refers to putting health problems in order of their importance. The factors that you should consider in prioritising are:

- the magnitude of the problem: e.g. how many cases are occurring over what period of time?

- the severity of the problem: how high is the risk of serious illness, disability or death?

- the feasibility of addressing the problem: are the prevention and control measures effective, available and affordable by the community?

- the level of concern of the community and the government about the problem.

Health problems which have a high magnitude and severity, which can be easily solved, and are major concerns of the community and the government, are given the highest priority. After prioritising which disease (or diseases) you will give most urgent attention to, the next step is to develop an action plan.

2.3.4 Action plan

An action plan sets out the ways in which you will implement the interventions required to prevent and control the disease. It contains a list of the objectives and corresponding interventions to be carried out, and specifies the responsible bodies who will be involved. It also identifies the time and any equipment needed to implement the interventions. Once you have prepared an action plan you should submit it for discussion with your supervisor and other officials in the woreda Health Office to get their approval. Then implement the work according to your plan.

Now that you have learned the basic concepts and methods relating to communicable diseases in general, it is time for you to move on to consider the diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control of specific diseases. In the next two study sessions, you will learn about the bacterial and viral diseases that can be prevented by vaccination.

Summary of Study Session 2

In Study Session 2, you have learned that:

- Communicable diseases can be classified based on their clinical or epidemiologic features.

- Clinical classification is based on the main clinical manifestations of the disease (e.g. diseases characterised by diarrhoea are classified as diarrheal diseases; diseases characterised by fever are febrile diseases).

- Epidemiologic classifications are based on the mode of transmission and include foodborne, waterborne, airborne and vector-borne diseases.

- Prevention and control measures for communicable diseases may target the reservoir of infection, the mode of transmission, or the susceptible host.

- Measures against a human reservoir include treatment and isolation. Measures against animal reservoirs can be treatment or destroying the animal.

- Measures against transmitters like food, water, other vehicles, and vectors, include hand washing with soap, effective use of latrines, destruction of breeding sites, disinfection, sterilisation and disinfestation.

- Measures to protect susceptible hosts include vaccination, keeping personal hygiene, use of bed nets and use of condoms.

- Community diagnosis of health problems involves data collection; data analysis; prioritising interventions based on the magnitude and severity of the problem, the feasibility of addressing it, and the level of concern; and making and implementing an effective action plan.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 2

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the questions below. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 2.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 2.1 and 2.2)

Tuberculosis (TB) is common in Ethiopia. Its main clinical manifestations include chronic cough and shortness of breath. Using this information, which classification of communicable diseases can you apply to TB and to which class does TB belong?

Answer

Using the given information, the classification could be based on the clinical manifestations of the disease (cough and shortness of breath); accordingly tuberculosis is classed as a respiratory disease.

SAQ 2.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 2.1 and 2.2)

How would you classify pulmonary tuberculosis using the epidemiologic method? What is the main importance of such classification?

Answer

Pulmonary tuberculosis is classified epidemiologically as an airborne disease. Such classification helps you in applying prevention and control measures against the disease.

SAQ 2.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 2.3, 2.4 and 2.5)

Suppose in a certain rainy season you diagnosed malaria in several people who came to you seeking treatment. Then, you undertook the following measures:

- a.You treated each patient with the appropriate drug.

- b.You mobilised the community to eradicate breeding sites of mosquitoes.

- c.You gave health education on the proper use of bed nets.

Which factor in the chain of disease transmission are you targeting with each of the above measures?

Answer

- a.Treatment of each patient targets the human reservoir.

- b.Eradication of breeding sites targets the mode of transmission.

- c.Bed net use targets the susceptible host.

SAQ 2.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 2.1, 2.3, 2.4 and 2.5)

Which of the following statements are true and which are false? In each case, explain your reasoning.

A Isolation of the susceptible host is advised for the duration of the incubation period of a severe and easily transmitted disease.

B Sterilisation refers to the destruction of all forms of micro-organisms by physical or chemical agents such as alcohol and chlorine.

C Vaccination and vector control target the infected host so as to prevent transmission of infection.

Answer

A is false. It is true that isolation is applied for severe and easily transmitted diseases, but it is applied to the infected hosts (not the susceptible hosts) until the risk of transmission is reduced or stops.

B is true. Sterilisation kills all forms of micro-organisms, unlike disinfection which kills most but not all forms.

C is false. Vaccination mostly targets the susceptible host and vector control targets the mode of transmission.

SAQ 2.5 (tests Learning Outcome 2.6)

Suppose among the diseases you have identified in your community, two are malaria and ascariasis (infection by ascaris worms). Let’s say the prevalence rate of malaria is 90 per 1,000 population and the prevalence rate of ascariasis is 200 per 1,000 population.

- a.If you need to prioritise activities to control one of these diseases, what other criteria should you consider?

- b.Malaria is a more severe disease than ascariasis. Let’s say that interventions for both diseases are equally feasible, but the community and government are more concerned about malaria. So, considering all the factors, to which disease do you give higher priority for prevention and control?

Answer

- a.The other criteria to be considered include the severity of the diseases, the feasibility of implementing effective interventions, and the concern of the community and the government.

- b.Malaria has priority in two out of the five criteria: that is severity, community and government concern, whereas ascariasis has priority in only one criterion, which is the higher prevalence. Both diseases have equal priority in feasibility of implementing interventions. Therefore, malaria should be given higher priority for prevention and control.