Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 13 March 2026, 11:41 PM

Communicable Diseases Module: 3. Bacterial Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

Study Session 3 Bacterial Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

Introduction

This study session and the next one focus on the communicable diseases that can be prevented by immunization with vaccines. Together they are known as vaccine-preventable diseases. In this study session you will learn about vaccine-preventable diseases caused by bacteria. In Study Session 4 we will describe those that are caused by viruses. Greater understanding of these diseases will help you to identify the ones that are common in your community, so that you can provide effective vaccination programmes, and identify and refer infected people for specialised treatment at a higher health facility.

You will learn about vaccines in detail in the Immunization Module.

In this study session, you will learn some basic facts about bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases, particularly how these diseases are transmitted, and how they can be treated and prevented. Our focus will be on tetanus and meningitis, because tuberculosis (TB), which is a bacterial vaccine-preventable disease, will be discussed in much more detail in Study Sessions 13–17 of this Module. Bacterial pneumonia (infection of the lungs), caused by bacteria called Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, is also discussed in detail later, in Study Session 35. A vaccine against Haemophilus influenzae is already being given to children in Ethiopia. A new vaccine against Streptococcus pneumoniae is planned to be introduced in Ethiopia, probably in 2011/2012.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 3

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

3.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3)

3.2 Describe what causes common bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases, how the infectious agents are transmitted, and the characteristic symptoms of an affected person. (SAQs 3.1 and 3.4)

3.3 Describe how the bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases tetanus and meningococcal meningitis can be treated, controlled and prevented in rural communities. (SAQs 3.2, 3.3 and 3.4)

3.1 Vaccines, immunity and vaccination

Before we can tell you about the vaccine-preventable diseases, you need to understand what is meant by a vaccine. Vaccines are medical products prepared from whole or parts of bacteria, viruses, or the toxins (poisonous substances) that some bacteria produce. The contents of the vaccine have first been treated, weakened or killed to make them safe. If a vaccine is injected into a person, or given orally by drops into the mouth, it should not cause the disease it is meant to prevent, even though it contains material from the infectious agent. Vaccines are given to susceptible persons, particularly children, so that they can develop immunity against the infectious agent (Figure 3.1).

As you will recall from Study Session 1, immunity refers to the ability of an individual to resist a communicable disease. When a dead or weakened micro-organism is given in the form of a vaccine, this process is called vaccination or immunization. For simplicity, in this Module we will refer to ‘vaccination’, but you should be aware that these two terms are used interchangeably.

The vaccine circulates in the body and stimulates white blood cells called lymphocytes to begin producing special defensive proteins known as antibodies. Antibodies are also normally produced whenever a person is infected with active bacteria or viruses transmitted from a reservoir in the community. Antibodies and white blood cells are very important natural defences against the spread of infection in our bodies, because they can destroy infectious agents before the disease develops. What vaccination does is to stimulate this normal response, by introducing a weakened or killed form of infection, which the white blood cells and antibodies attack.

This defensive response against the harmless vaccine increases the person’s level of immunity against the active infectious agents, if the same type that was in the vaccine gets into the body. The protective effect of vaccination lasts for months or years afterwards, and if several vaccinations are given with the same vaccine, the person may be protected from that infection for their lifetime. The Module on Immunization will teach you all about the vaccines available in Ethiopia in the Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI), and how they are stored and administered in vaccination programmes.

3.2 Overview of bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases

Vaccine-preventable diseases are important causes of death in children. The causes, infectious agents, modes of transmission, symptoms, and methods of prevention, treatment and control of the most important bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases are summarised in Table 3.1. Note that some of the diseases shown in Table 3.1, such as diphtheria and pertussis, are no longer common in Ethiopia, or in other countries where vaccination in childhood against their infectious agents is widespread. Tuberculosis and bacterial pneumonia are discussed in detail in later study sessions.

In this study session, we will describe tetanus and bacterial meningitis, so that you will be able to identify and refer cases of these diseases, and also know how you might help to prevent them in your community.

| Disease | Bacterial cause (scientific name) | Mode of transmission | Symptoms | Prevention and control methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Respiratory by coughing or sneezing | Chronic cough, weight loss, fever, decreased appetite (more details are given in Study Session 13) | BCG vaccine, chemoprophylaxis, early diagnosis and treatment |

| Diphtheria | Corynebacterium diphtheriae and its toxin | Respiratory by coughing or sneezing | Sore throat, loss of appetite, and slight fever | Diphtheria vaccine, combined with two or four other vaccines against pertussis, tetanus, BCG, etc. |

| Pertussis | Bordetella pertussis | Respiratory by coughing or sneezing | Runny nose, watery eyes, sneezing, fever, and continuous cough, followed by vomiting | Pertussis vaccine, combined with two or four other vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, BCG, etc. |

| Tetanus | Clostridium tetani | From soil into a wound or broken skin, through direct contact | Stiffness in the jaw and neck, with stomach and muscle spasms | Tetanus vaccine for children, combined with other vaccines, or given alone for women of childbearing age |

| Meningitis (infection of the brain or spinal cord) | Neisseria meningitidis | Respiratory by coughing or sneezing | Fever, headache, neck stiffness, coma | Meningococcal vaccine and treatment by antibiotics |

Streptococcus pneumoniae | Respiratory by coughing or sneezing | Fever, headache, neck stiffness, coma | Treatment by antibiotics; a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) will be introduced to Ethiopia soon | |

| Pneumonia (infection of the lungs) | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Respiratory by coughing or sneezing | Cough, fast breathing/difficult breathing (more details are given in Study Session 35) | Treatment by antibiotics; a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) will be introduced to Ethiopia soon |

Haemophilus influenzae | Respiratory by coughing or sneezing | Cough, fast breathing/difficult breathing (more details are given in Study Session 35) | Treatment by antibiotics; Hib is part of the pentavalent vaccine |

3.3 Tetanus

In this section, you will learn about what tetanus is, how it is transmitted, what its clinical symptoms are, and how it can be treated and prevented. Having this information will help you to identify cases of tetanus and refer them to the nearby hospital or health centre for further treatment. All cases should be reported to the District Health Office. After reading this section, you should also be able to educate your community about the causes of tetanus, and how to prevent it. You will learn how to give the tetanus toxoid vaccine to children, and to women of reproductive age, in the Module on Immunization.

3.3.1 Definition, cause and occurrence of tetanus

Tetanus is a neurological disorder, that is, a disorder of the nervous system. Symptoms of tetanus are tight muscles that are difficult to relax, and muscle spasms (muscle contractions that occur without the person wanting them to). These problems with the muscles are caused by a toxin (poison) produced by the bacteria called Clostridium tetani.

Tetanus is among the top ten causes of illness and death in newborns in Ethiopia. Tetanus in newborns is called neonatal tetanus. Nine out of every 1,000 newborns in Ethiopia have neonatal tetanus. More than 72% of the newborns who have tetanus will die.

Tetanus is also common among older children and adults who are susceptible to the infection. Unvaccinated persons are at risk of the disease, and people who have a dirty wound which favours the growth of the bacteria that cause tetanus are especially vulnerable.

3.3.2 Mode of transmission of tetanus

People can get tetanus through exposure to tetanus bacteria (Clostridium tetani) which are always present in the soil. The bacteria can be transmitted directly from the soil, or through dirty nails, dirty knives and tools, which contaminate wounds or cuts. A newborn baby can become infected if the knife, razor, or other instrument used to cut its umbilical cord is dirty, if dirty material is used to dress the cord, or if the hands of the person delivering the baby are not clean. Unclean delivery is common when mothers give birth at home in poor communities, but it can be prevented by skilled birth attendants (Figure 3.2).

The disease is caused by the action of a toxin produced by the bacteria, which damages the nerves of the infected host. This toxin is produced during the growth of the tetanus bacteria in dead tissues, in dirty wounds, or in the umbilicus following unclean delivery of the newborn.

3.3.3 Clinical manifestations of tetanus

The time between becoming infected with Clostridium tetani bacteria and the person showing symptoms of tetanus disease is usually between three and 10 days, but it may be as long as three weeks.

What is the name given to the gap in time between infectious agents entering the body, and the first appearance of the disease they cause? (You learned this in Study Session 1.)

It is called the incubation period.

In cases of tetanus, the shorter the incubation period, the higher the risk of death. In children and adults, muscular stiffness in the jaw, which makes it difficult or impossible to open the mouth (called ‘locked jaw’) is a common first sign of tetanus. This symptom is followed by neck stiffness (so the neck cannot be bent), difficulty in swallowing, sweating, fever, stiffness in the stomach muscles, and muscular spasms (involuntary contraction of the muscles).

Babies infected with tetanus during delivery appear normal at birth, but they become unable to feed by suckling from the breast at between three and 28 days of age. Their bodies become stiff, while severe muscle contractions and spasms occur (Figure 3.3). Death follows in most cases.

A newborn baby (10 days old) who was born in a village with the assistance of traditional birth attendants, is brought to you with fever, stiffness in the stomach muscles and difficulty in opening his mouth, so he is unable to breastfeed. What is the possible cause of this baby’s symptoms, and why do you make this diagnosis? What action will you take?

The newborn may have tetanus since he was born at home without the care of a skilled birth attendant. The umbilical cord could be infected by tetanus. You should refer this child urgently to the nearest health centre or hospital.

The newborn may have tetanus since he was born at home without the care of a skilled birth attendant. The umbilical cord could be infected by tetanus. You should refer this child urgently to the nearest health centre or hospital.

3.3.4 Treatment, prevention and control of tetanus

Once a person has tetanus, he or she will be treated by an antibiotic drug. Antibiotics are medicines that destroy bacteria, or stop them from multiplying in the body. However, many people who have tetanus die despite the treatment. Hence, prevention is the best strategy, and vaccination is the best way to prevent tetanus.

Tetanus toxoid (TT) vaccination

The tetanus vaccine contains inactivated tetanus toxoid (poison), which is why it is often called TT vaccine. Tetanus toxoid vaccination is given routinely to newborns and infants as part of the threefold DPT vaccine (with diphtheria and pertussis vaccines), or the pentavalent (fivefold) vaccine, which includes vaccines for diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, Hepatitis B (a virus), and a bacterium called Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib). Neonatal tetanus can also be prevented by vaccinating women of childbearing age with tetanus toxoid vaccine, either during pregnancy or before pregnancy. This protects the mother and enables anti-tetanus antibodies to be transferred to the growing fetus in her uterus.

What is the name given to this mode of transmission? (You learned about it in Study Session 1 in reference to infectious agents being transferred from mother to baby).

The transmission from mother to fetus is called transplacental transmission because the mother’s antibodies pass across the placenta and into the baby.

Cleanliness is also very important, especially when a mother is delivering a baby, even if she has been vaccinated with TT vaccine.

People who recover from tetanus do not have increased natural immunity and so they can be infected again. Therefore they will need to be vaccinated.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF set a goal to eliminate neonatal tetanus by 2005. Elimination in this case would mean that the number of neonatal tetanus cases would have to be reduced to below one case per 1,000 live births per year in every district. Notice that elimination of a communicable disease does not mean there are no cases — just very few right across a country or region. Eradication means the total and sustained disappearance of the disease from the population.

Do you think that tetanus can ever be eradicated? Explain why, or why not.

Because tetanus bacteria survive in soil in the environment, eradication of the disease is not possible.

To achieve the elimination goal, countries like Ethiopia, with a high number of tetanus cases every year, need to implement a series of prevention strategies, which include those listed in Box 3.1.

Clean delivery practices are described in the Labour and Delivery Care Module.

Box 3.1 Strategies to prevent and control tetanus

- Vaccinating a higher percentage of pregnant women against tetanus with vaccines containing tetanus toxoid (TT).

- Vaccinating all females of childbearing age (approximately 15–45 years) with TT vaccine in high-risk areas where vaccination coverage is currently low.

- Outreach vaccination campaigns where health workers go to rural villages and give TT vaccine, usually three times at intervals (known as a ‘three-round’ vaccination campaign).

- Promoting clean delivery and childcare practices, through better hygiene and care of the newborn’s umbilicus.

- Improving surveillance and reporting of cases of neonatal tetanus. The case finding and reporting will help us to give appropriate treatment and vaccination to children.

3.4 Meningococcal meningitis

![]() Cases of meningitis must be referred urgently for medical treatment.

Cases of meningitis must be referred urgently for medical treatment.

In this section, we will describe what meningococcal meningitis is, how it is transmitted, what its clinical symptoms are, and also how it can be treated and prevented. With this information, we hope you will be able to identify a person with meningitis and refer him or her urgently to the nearest health centre or hospital for further diagnosis and treatment. You should also be able to detect meningococcal meningitis epidemics in the community.

3.4.1 Definition and cause of meningococcal meningitis

Meningococcal meningitis is an infection of the brain and spinal cord by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis (also known as the meningococcus bacterium). The disease is caused by several groups of meningococcus bacteria, which are given distinguishing codes such as type A, B, C, Y and W135.

In populations over 30,000 people, a meningitis epidemic is defined as 15 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per week; or in smaller populations, five cases in one week or an increase in the number compared to the same period in previous years.

The disease occurs globally, but in sub-Saharan Africa, meningitis epidemics occur every two to three years. An epidemic is a sudden and significant increase in the number of cases of a communicable disease, which may go on rising for weeks, months or years. Meningitis epidemics are common in many countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, including Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, these epidemics are usually caused by group A and C type meningococcus bacteria, and are more common in western Ethiopia. The disease is most common in young children, but it also can affect young adults living in crowded conditions, in institutions, schools and refugee camps.

3.4.2 Mode of transmission and clinical symptoms

Meningococcal meningitis is transmitted to a healthy person by airborne droplets from the nose and throat of infected people when they sneeze or cough. The disease is marked by the sudden onset of intense headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and stiffness of the neck. Other signs include lethargy (extreme lack of energy), coma (loss of consciousness), and convulsions (uncontrollable shaking, seizures). Box 3.2 summarises the general signs of meningitis, which may also be caused by some other serious conditions, and the more specific signs which are characteristic of meningitis.

Box 3.2 General and more specific signs of meningitis in infants

General signs of meningitis:

- Drowsy, lethargic or unconscious

- Reduced feeding

- Irritable

- High pitched cry.

More specific signs of meningitis:

- Convulsion (fits)

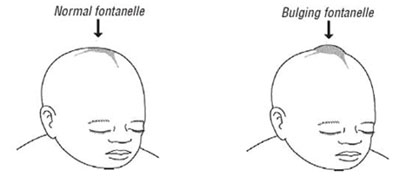

- Bulging fontanelle in infants.

![]() A child with typical signs of meningitis such as neck stiffness, bulging fontanelle and convulsion, should be immediately referred to the nearest hospital or health centre.

A child with typical signs of meningitis such as neck stiffness, bulging fontanelle and convulsion, should be immediately referred to the nearest hospital or health centre.

During examination of a baby with meningitis, you will notice stiffness of the neck, or bulging of the fontanelle – the soft spot on top of the head of infants (see Figure 3.4). The fontanelle bulges because the infection causes fluid to build up around the brain, raising the pressure inside the skull. A bulging fontanelle due to meningitis is observed in infants since the bones of the skull are not yet fused together.

Children may also show rigid posture due to irritation of the covering part of the brain or spinal cord. To check the presence of neck stiffness, ask the parents to lay the child in his/her back in the bed and try to flex the neck of the child (Figure 3.5).

If meningitis is not treated, mortality is 50% in children. This means that half of all cases end in death. However, with early treatment, mortality is reduced to between 5 to 10%. But about 10 to 15% of those surviving meningococcal meningitis will suffer from serious complications afterwards, including mental disorders, deafness and seizures.

3.4.3 Diagnosis and treatment of meningitis

Meningitis is diagnosed by physical examination of the person, and by laboratory testing of the fluid from their spinal cord, where the meningococcal bacteria can be found. In the hospital or health centre, the meningitis is treated using antibiotics given intravenously (IV), that is, liquid antibiotics given directly into the bloodstream through a vein.

Tetanus and meningitis are both diseases in which fever and stiffness of the neck are important symptoms. How could you tell these diseases apart in babies by examining them yourself?

Tetanus and meningitis can both be manifested by fever and neck stiffness, but there are other specific signs of each disease which help in differentiation. For instance, people with tetanus may have tightness of the abdominal muscles and may be unable to open their mouths. By contrast, the bulging fontanelle is a typical sign of meningitis in young babies, which would not be found in cases of tetanus. However, these diseases are very difficult to distinguish on the basis of clinical examination alone.

3.4.4 Prevention and control of meningococcal meningitis

Next we describe how to prevent meningococcal meningitis from spreading in a community. The most important preventive and control methods are summarised in Box 3.3.

Box 3.3 Strategies to prevent and control meningitis

- Early identification and prompt treatment of cases in the health facility and in the community.

- Education of people in the community on the symptoms of meningitis, the mode of transmission and the treatment of the disease.

- Reporting any cases of meningitis to the District Health Office; and avoiding close contact with the sick persons. Your health education messages should tell everyone about this.

- Vaccination against meningococcus bacteria of types A, C, Y and W135, as described in the Immunization Module.

A mass immunization campaign that reaches at least 80% of the entire population with meningococcus vaccines can prevent an epidemic. However, these vaccines are not effective in young children and infants, and they only provide protection for a limited time, especially in children younger than two years old. A single case of meningitis could be a warning sign for the start of an epidemic. As a community Health Extension Practitioner, you will need to educate your community about the symptoms of meningitis and how it is transmitted. All cases should be reported to the District Health Office.

The next study session is also about vaccine-preventable diseases, but we turn your attention to those common diseases of this type that are caused by viruses.

Summary of Study Session 3

In Study Session 3, you have learned that:

- Vaccine-preventable diseases are communicable diseases that can be prevented by immunization with vaccines containing weakened or killed infectious organisms or their toxins.

- Vaccination increases the level of immunity in the body to the infectious agents that were used to make the harmless vaccine.

- Tuberculosis, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, meningococcal meningitis and streptococcal pneumonia are the commonest and the most important bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases.

- Tetanus and meningococcal meningitis are bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases that cause many deaths of children and adults in developing countries.

- Tetanus bacteria (Clostridium tetani) live in the soil and enter the body through wounds, breaks in the skin and, in the newborn, in the umbilical cord after it has been cut.

- The symptoms and signs of tetanus include rigid posture, stiffness in the jaw and neck, difficulty in swallowing, sweating, fever, stiffness in the stomach muscles and muscular spasms.

- Clean delivery of babies by trained health professionals, and vaccination of children and women in the reproductive age groups with tetanus toxoid (TT) vaccine, are the most important strategies for preventing neonatal tetanus.

- Meningococcal meningitis is caused by Neisseria meningitidis (or the meningococcus bacteria); they are passed from person to person in airborne droplets when the infected host coughs or sneezes, sometimes causing epidemics.

- A person who has signs of meningitis, such as high fever, neck stiffness,lethargy and loss of consciousness, or bulging of the fontanelle in babies, should be referred immediately to the nearest hospital or health centre.

- Cases of tetanus or meningococcal meningitis in the community should be reported to the District Health Office.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 3

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 3.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.1 and 3.2)

Mention two or more bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases that have the same modes of transmission.

Answer

Pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, pertussis and diphtheria all have the same mode of transmission: they are airborne bacteria.

SAQ 3.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.1 and 3.3)

What are the methods for preventing bacterial meningitis?

Answer

The preventive strategies of meningitis include early case identification and treatment, education of the community on the preventive methods such as avoiding close contacts with meningitis cases, and vaccination against meningitis.

SAQ 3.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.1 and 3.3)

If you observe a child who has a fever, neck stiffness and a rigid posture, as shown in Figure 3.6, what is the likely cause? What action will you take and why?

Answer

Fever, neck stiffness and rigid posture (as in Figure 3.6) are the signs of meningitis in a child. A young baby will also have bulging of the fontanelle. Tetanus can also be manifested with rigid posture. You should immediately inform the family and refer the child to hospital for urgent diagnosis and treatment.

SAQ 3.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.2 and 3.3)

Mention two major bacteria that commonly cause meningitis. Can you differentiate between the symptoms caused by these bacteria? What would you do if you encounter a person with these symptoms?

Answer

Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the two major bacteria that cause meningitis in children and adults. The two bacteria have similar symptoms (Table 3.1) and it is difficult to differentiate them by symptoms alone. As a Health Extension Practitioner, you need to refer patients with symptoms of meningitis to the nearest hospital or health centre.