Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 13 March 2026, 2:39 PM

Communicable Diseases Module: 14. Diagnosis and Treatment of Tuberculosis

Study Session 14 Diagnosis and Treatment of Tuberculosis

Introduction

In this study session you will learn about methods for diagnosis of tuberculosis, be introduced to different categories of patient with TB and also learn about treatment of tuberculosis with drugs, including the major side-effects of these medications. Even though you are not the person with responsibility for diagnosing and prescribing anti-TB drugs, having this information will enable you to swiftly identify and refer people suspected of having TB and ensure there is follow-up for confirmed cases. You will also learn more about the main method of diagnosis of TB, which is sputum examination under a microscope, and other supportive measures like chest X-ray, which is likely to help diagnosis of individuals who are smear-negative.

Your role is to make sure that every person diagnosed with TB takes the recommended drugs, in the right combinations and at the right time, for the appropriate duration. The best way to achieve this is for you to watch each patient swallow the drugs. This is called Directly Observed Treatment, Short Course (DOTS) and was introduced in Study Session 13. Directly observed treatment can take place at a hospital, health centre or health post, the patient’s workplace or home. If drugs are taken incorrectly or irregularly, the patient will not be cured and drug resistance may arise. To a large extent, the success of TB treatment by drugs depends on your effectiveness in overseeing the patient’s adherence to the treatment.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 14

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

14.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 14.1, 14.2 and 14.3)

14.2 Describe methods used to diagnose tuberculosis and the different types of case definitions. (SAQ 14.2)

14.3 Describe different treatment categories used to treat tuberculosis. (SAQs 14.2 and, 14.3)

14.4 Describe the main drugs used to treat tuberculosis and the processes that help you ensure patients are following the correct treatment schedules. (SAQ 14.3)

14.5 Describe the potential side-effects associated with the drugs used to treat tuberculosis and explain how such side effects are managed. (SAQ 14.4)

14.1 Diagnostic methods

In Study Session 13 you learnt about the clinical symptoms of TB. They are a cough for two or more weeks, spitting up blood in the sputum, weight loss, fever or night sweats for three or more weeks, fatigue, and loss of appetite, chest pains or difficulty breathing.

If a person comes to you complaining of a persistent cough that has lasted for over two weeks and they are also producing whitish sputum, what should you do?

Sputum is a secretion coughed up from the lungs and expectorated (expelled) through the mouth.

This person is showing symptoms that are consistent with an active TB infection. You should obtain sputum samples from this individual to send for sputum examination to confirm the diagnosis.

Remember, taking a history from the person you suspect of having TB will allow you to determine if they need to be referred for a sputum examination.

If you ask the right questions and make the right observations, you will be able to identify those individuals who you suspect of having TB. What to look for depends on the type of TB involved. The key symptoms of both forms of TB are summarised in Box 14.1.

Box 14.1 Key symptoms of both forms of TB

Active Pulmonary TB disease (PTB)

A low grade fever is defined as a slight increase in body temperature that does not exceed 38.5oC.

Pulmonary TB has several manifestations. The most common and obvious one is a persistent cough that lasts for two weeks or more which is usually accompanied with the production of whitish sputum.

Other key symptoms are spitting of blood, weight loss, low grade fever, loss of appetite, night sweating, chest pain and shortness of breath or difficulty in breathing. Any person with persistent cough of two or more weeks (with or without any of these other symptoms) should be suspected of having TB and you should refer them for a sputum examination.

Extra-Pulmonary TB disease (EPTB)

![]() Persons with one or more of these symptoms should be investigated for extra-pulmonary TB and referred urgently to a health facility.

Persons with one or more of these symptoms should be investigated for extra-pulmonary TB and referred urgently to a health facility.

The symptoms of EPTB will vary depending on the organ affected (this was summarised in the previous Study Session in Table 13.2), but they can include: back pain, swelling on the spine, long-lasting bone infection, painful joint swelling (usually affecting one joint), painful urination, blood in urine, frequent urination, hoarseness of voice, pain on swallowing, headache, fever, neck stiffness, vomiting, irritability, convulsions, swelling of the lymph node with draining pus and long-lasting ulcers resistant to antibiotic treatment.

We will now describe in more detail different methods used to diagnose tuberculosis and other procedures that are used to diagnose extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB). Diagnosis of tuberculosis is made at health centres and hospitals, but you will make a vital contribution by identifying those individuals who may be infected with TB and referring them for investigation. Part of your role is to provide information and counsel those who are about to undergo diagnostic investigation and treatment.

14.1.1 Microscopic examination of sputum smears

Sputum microscopy is the most efficient way of identifying a tuberculosis infection. It is the primary tool used for diagnosing TB and for monitoring the progress of treatment until the patient is cured. You are expected to oversee the collection of sputum samples during initial diagnosis, and at various times during drug treatment to monitor the effectiveness of the treatment.

You will recall from Study Session 13 that three sputum samples will be collected over two consecutive days, and that one of the sputum samples is collected in the morning. The samples are sent to a laboratory and Figure 14.1 illustrates a health professional examining a sputum smear using a microscope. The smear is treated with chemicals that reveal the presence of TB bacteria and these can be seen using a microscope (they cannot be seen with the naked eye). The examined specimens are classified as being either smear-positive pulmonary TB or smear-negative. However, you should know that a smear-negative result could either mean the patient has TB but it is not showing in the sputum, or that the person does not have TB.

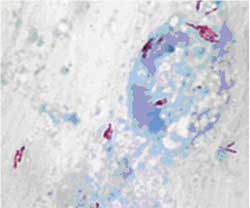

An example of a positive smear, seen under a microscope, is shown in Figure 14.2. The smear has been stained with chemicals to reveal the presence of TB bacteria (they appear as purple rod-shaped bacteria).

A diagnosis of TB is made if at least two out of the three sputum smears are positive for TB bacteria. TB is also confirmed if one sputum specimen is positive for bacteria, and there is also evidence of abnormalities in a chest X–ray. Finally, in people living with HIV (or in the presence of a strong clinical suspicion of HIV infection), only one positive smear result is necessary to make a diagnosis of smear-positive pulmonary TB.

14.1.2 Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray can only be ordered by a doctor or a clinician.

Chest X-ray is another tool used in diagnosing TB. It is particularly important when diagnosing TB in individuals who are smear-negative for the TB bacteria or who are unable to produce sputum. It is also an important diagnostic tool for those persons who may have extra-pulmonary tuberculosis; such individuals may not be able to produce sputum and should be referred to the doctor/clinician for a chest X-ray. It is also possible to have EPTB and a normal chest X-ray.

What distinguishes EPTB from PTB?

In EPTB the active infection occurs in an organ other than the lungs (see Study Session 13, Table 13.2 for a list of organs that can be affected and the symptoms associated with EPTB infection).

Why do you think a chest X-ray is useful in diagnosing TB?

If you recall from Study Session 13, TB enters the body via inhalation of droplet nuclei contaminated with TB bacteria. Because they enter the body via the lungs they produce changes in the lungs that can be seen on a chest X-ray.

14.1.3 TB culture from sputum

A culture involves growing the bacteria in the laboratory; this test can only be ordered by a doctor or a clinician.

Culturing of TB bacteria from a sputum sample in the laboratory is very expensive and takes several weeks to produce a result; however it is a very sensitive and highly specific tool. It plays a key role in identifying the type of drug-resistant TB found in a patient, such as those patients who are not responding to treatment as well as expected. Culture with Drug Sensitivity Testing (DST will be covered in Study Session 16) takes even longer; but provides crucial information about which antibiotics will kill the bacteria isolated from the patient. You should send patients for TB culture and DST if they are suspected of drug-resistance.

14.1.4 Biopsy

Biopsy is an important tool used to diagnose extra-pulmonary TB. It is the removal and examination of tissues from the living body to determine the existence or cause of a disease. It involves the microscopic examination of a small specimen of tissue extracted from the patient’s body. It is particularly useful for diagnosing extra-pulmonary TB in the lymph nodes and joints, as well as other affected organs. It can also be used to confirm pulmonary TB by sampling lung tissue in smear-negative suspects. Again, only doctors and clinicians are allowed to request this type of examination to diagnose TB.

14.2 Treatment of tuberculosis

The main objectives of anti-TB treatments include: to cure TB patients (by rapidly eliminating most of the bacteria), to prevent death or organ damage from active TB, to prevent relapse of TB (by eliminating the inactive bacteria), to prevent the development of drug resistance (by using a combination of drugs) and importantly to decrease TB transmission to others.

14.2.1 Classifications of TB and treatment categories

Classifications of TB cases are based on the following factors and you will see these terms used when cases are confirmed:

- organ involved: pulmonary or extra-pulmonary

- sputum result: smear-positive or smear-negative

- history of TB treatment: new or previously treated or relapsed

- severity of the disease: severe or not severe (covered later in this study session).

14.2.2 Definition of types of TB cases

You are already aware that a ‘case of TB’ is an individual in whom tuberculosis has been confirmed by microscopic examination, or diagnosed by a clinician or medical doctor.

However, there are several different types of TB cases (in other words different case definitions) and these are based on the smear result, history of previous treatment and severity of disease. These different case definitions are listed in Table 14.1, from which you’ll also see that if a patient does not fall into any of the main types, they are registered as ‘other’.

Knowing these different case definitions will help in your recording and reporting of cases, as well as giving you important information about the infectiousness of the patient, the risk of drug resistance, and where there is a need for follow-up of patients.

| Type of patient | Case definition |

|---|---|

| New | A patient who has never had treatment for TB, or has been on anti-TB treatment for less than four weeks. |

| Relapse | A patient who has been declared cured or treatment completed for any form of TB in the past, but who reports back to the health service and is found to be sputum smear-positive or culture positive. |

| Treatment after previous treatment failure | A patient who, while on treatment remained sputum smear-positive or became sputum smear-positive at the end of the five months or more, after commencing treatment. |

| Treatment after default (did not complete previous treatment) | A patient who had previously been recorded as defaulted from treatment and returns to the health service with smear-positive sputum. |

| Transfer in | A patient who is transferred from another district to continue treatment. |

| Other | A patient who does not fit into any of the above categories. |

| Chronic case | A patient who is still sputum smear-positive at the completion of a re-treatment regimen. |

14.3 Patient categories and treatment regimens

In order to establish treatment priorities, the WHO recommends that TB patients should be classified into four categories, as shown in Table 14.2. Patients are started on anti-TB drugs according to their category.

![]() You should refer patients with the following symptoms urgently to hospital for proper management:

You should refer patients with the following symptoms urgently to hospital for proper management:

- Coughing up blood

- Increasing breathlessness

- Suddenly increasing chest pain

- Progressively deteriorating general condition.

| Treatment category | Type of patient |

|---|---|

| I | Sputum smear-positive; new Sputum smear-negative; seriously ill, new EPTB; seriously ill, new Others (e.g. TB with HIV infection) |

| II | Sputum smear-positive; relapse Sputum smear-positive; failure Sputum smear-positive; return after default PTB patients who become smear-positive after two months of treatment (case definition = other) Return after default from re-treatment Relapses after re-treatment |

| III | Sputum smear-negative, not seriously ill, new EPTB, not seriously ill, new |

| IV | Chronic and drug resistant-TB cases (still sputum positive after supervised re-treatment) |

Always keep in mind that patients with severe forms of EPTB may come to you with the types of symptom mentioned in Study Session 13, Table 13.2 — perhaps with TB affecting the lining of the brain (TB meningitis) or the kidney (renal TB) or the spine (spinal TB). You must refer such patients to the hospital for proper management because they need additional medication and/or special care. Disseminated TB is often used to describe TB involving two or more organs or tissues of the body and it is considered as one of the severe forms of TB.

14.3.1 Treatment regimens for different TB categories

A regimen is a defined course of drug treatment.

If you are already a health worker, you will be familiar with the types of anti-TB drugs used in Ethiopia. However, we will teach the regimens here in detail because they may have been updated since you learned about them. The first line anti-TB drugs used are (drug abbreviation in brackets):

rifampicin (R), ethambutol (E), isoniazid (H), pyrazinamide (Z) and streptomycin (S).

Vials are small glass bottles of liquid injectable medications (or vaccines).

These drugs are provided in combination. For instance R, H, Z and E are combined in one preparation in the proportions (RHZE 150/75/400/275 mg). Similarly, two drugs can be combined in one preparation, for example R and H are combined (RH 150/75 mg), and so are E and H (EH 400/150 mg). Some drugs are available as single drug preparations; such as ethambutol 400 mg, isoniazid 150 mg and 300 mg, and streptomycin sulphate vials (1 g). Streptomycin is administered by injection while the other drugs are taken orally. All the drugs should be taken by patients together as a single, daily dose, preferably on an empty stomach to improve drug absorption.

14.3.2 Phases of chemotherapy

The chemotherapy (drug treatment) of tuberculosis has two phases, known as the intensive and the continuation phases.

Intensive phase

The intensive phase consists of four or more drugs for the first eight weeks for new cases, and 12 weeks for re-treatment cases. It makes the patient non-infectious by rapidly reducing the load of bacteria in the sputum, usually within two to three weeks (except in cases of drug resistance). During the intensive phase, the drugs must be collected daily by the patient and must be swallowed under the direct observation (DOTS) of you or another health worker or a treatment supporter.

Continuation phase

The continuation phase immediately follows the intensive phase and is important to ensure completion of treatment and a cure; it is essential to avoid relapse after completion of treatment. This phase requires at least two drugs, to be taken for four or six months in the case of Category I and Category III patients, or for five months for Category II patients. During the continuation phase, you should encourage the patient to go and collect the drugs every month — perhaps you can accompany the patient to collect the drugs — and then follow-up to ensure that the patient is taking their medication properly.

14.3.3 Treatment regimens

According to WHO recommendations and the national guidelines that apply in Ethiopia, the following treatment regimens should be used:

Note that the number before the bracket refers to the number of months the drug is taken.

Category I and III patients are treated in the intensive phase with combinations of four ‘first-line’ drugs: isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for two months, which can be summarised as 2 (HRZE). In the continuation phase, they receive either a combination of isoniazid and rifampicin for four months 4 (HR), or a combination of isoniazid and ethambutol for six months 6 (HE).- For Category I patients with a smear-positive sputum result after two months of intensive treatment, extend the intensive phase for an additional one month. Then follow the continuation phase as above. If a patient is still smear-positive after five months of treatment, then they need to be categorised as ‘treatment failure’ and restart treatment (Category II).

- Category II patients are treated with five drugs for the initial two months of the intensive phase: a combination of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol 2 (HRZE), plus streptomycin (S); then continue with four drugs, excluding streptomycin, for an additional one month; then followed by five months of the continuation phase with isoniazid, rifampicin 5 (HR), and ethambutol (E).

- Category IV patients are treated with ‘second-line’ anti-TB drugs, which you do not need to know the details of.

These different treatment regimens are summarised in Table 14.3.

| Treatment category | TB treatment regimen | |

|---|---|---|

| Intensive phase (daily or three times every week) | Continuation phase (daily or three times every week) | |

| I | 2 (HRZE) | 4 (HR) or 6 (HE) |

| II | 2 (HRZES) followed by 1 (HRZE) | 5 (HRE) |

| III | 2 (HRZE) | 4 (HR) or 6 (HE) |

| IV | Second-line drugs | Second-line drugs |

Knowing this information will enable you to understand the type of drug regimen prescribed by the doctor or clinician for different patient categories. This will help you ensure that the drug treatment is being followed correctly.

Tables 14.4 and 14.5 show the amounts of the different drugs to be administered to patients — in particular the number of tablets they take at any one time. The number of tablets depends upon the body weight of the patient. You are not expected to know the precise dosage of each drug — for example how many milligrams of isoniazid is taken when the patient takes their tablets — but it is very important for you to know the number of tablets a particular patient should be taking. So it is important to check the weight of your patients periodically and refer them to a clinician for an adjustment of drug dose if there is change in their body weight during treatment.

| Regimen | Intensive phase (2 months) | Continuation phase (6 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 (HRZE) daily | 6 (HE) daily | ||

| H 75 mg + R 150 mg + Z 400 mg + E 275 mg tablets | H 150 mg + E 400 mg tablets | ||

| Patient’s weight | Number of tablets | Number of tablets | |

| 20–29 kg | 1½ | 1 | |

| 30–39 kg | 2 | 1½ | |

| 40–54 kg | 3 | 2 | |

| 55–70 kg | 4 | 3 | |

| Over 70 kg | 5 | 3 | |

Table 14.4 shows the 2 (HRZE) and 6 (HE) drug regimen for categories I and III. The Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health have now approved a move to the adoption of 4 (HR) in the continuation phase in such cases, which means four months of isoniazid and rifampicin. It may be some time before 4 (HR) becomes the standard in such cases, so in Table 14.3 both 6 (HE) and 4 (HR) are shown.

| Regimen | Intensive phase (3 months) | Continuation phase (5 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 (HRZES) then 1(HRZE) daily | 5 (HRE) (three times per week) | ||

| H 75 mg + R 150 mg + Z 400 mg + E 275 mg tablets | S (vials) 1 g intramuscular | H 75 mg + R 150 mg + E 400 mg tablets | |

| Patient’s weight (kg) | Number of tablets | Number of vials | Number of tablets |

| 20–29 kg | 1½ | ½ | 1½ + 1 |

| 30–39 kg | 2 | ½ | 2 + 1½ |

| 40–54 kg | 3 | ¾ | 3 + 2 |

| 55–70 kg | 4 | 1 | 4 + 3 |

| Over 70 kg | 5 | 1 | 5 + 3 |

What is the regimen prescribed for the Category II relapsed TB patient?

The drug regimen used for Category II is 2 (HRZES), then 1 (HRZE), then 5 (HRE). Because the intensive phase is three months, but streptomycin is used for only two months (56 doses), it is helpful to write a reminder on the card about when to stop streptomycin.

14.3.4 Anti-TB drug treatment in special situations

Pregnancy

Anti-TB drug treatment for people with HIV on antiretroviral drugs will be discussed in Study Session 16.

Be sure to ask women patients whether they are pregnant. Most anti-TB drugs are safe for use in pregnancy, with the exception of streptomycin, because this can cause permanent deafness in the baby. Pregnant women who have TB must be treated, so ethambutol is used instead of streptomycin. Refer pregnant TB patients to a clinician who can prescribe the appropriate anti-TB drug regimen.

Oral contraception

Rifampicin interacts with oral contraceptive medications with a risk of decreased protection against pregnancy. A woman who takes the oral contraceptive pill (which you’ll probably know is medication used for preventing pregnancy) may choose between two options while receiving treatment with rifampicin, following consultation with a clinician. She could either take an oral contraceptive pill containing a higher dose of oestrogen (50 µg), or she could use another form of contraception. You should be in a position to give advice on the options for women in this situation; the Module on Family Planning will give you more guidance on topics such as this.

Breastfeeding

A breastfeeding woman who has TB can be treated with the regimen appropriate for her disease classification and previous treatment. The mother and baby should stay together and the baby should continue to breastfeed in the normal way.

The benefits of breastfeeding to the baby are greater than the risk of getting TB from the mother, or diarrhoeal diseases when the baby is fed with animal or formula milk using a feeding bottle. However, you need to advise the mother to take her child for screening for TB to a higher health facility. If the baby is not infected with TB, he or she will be provided with isoniazide preventive therapy. It is also important that the mother cover her mouth during coughing or sneezing, to prevent TB transmission to the baby.

14.3.5 Treatment of TB patients under Directly Observed Treatment (DOTS)

WHO recommends that directly observed treatment continue through the continuation phase if the regimen includes rifampicin.

As you appreciate from Study Session 13, DOTS is essential during the intensive phase of treatment (the first two to three months); it will also be needed during the continuation phase for patients with previous treatment failure who are being re-treated. Directly observed treatment ensures that the drugs are taken in the right combinations and on schedule, and that the patient continues treatment until all the doses have been taken. The health facility is the recommended place for treatment because of the ease of supervision. However, some patients live far away or do not find it convenient to come to a health facility, in which case you need to directly observe treatment at a place and time more convenient for them.

14.4 Side-effects of anti-TB drugs and their management

14.4.1 Types and severity of side-effect

Side-effects are unwanted symptoms, discomfort or more serious adverse (harmful) consequences of drug treatment. Serious side-effects are rare in patients taking anti-TB drugs. A minority of TB patients treated with Category I or Category II regimens experience adverse side-effects categorised as:

- major adverse side-effects giving rise to serious health concerns that require the stopping of anti-TB treatment

- minor side-effects causing relatively little discomfort and often responding to simple treatment of the symptoms; they may occasionally persist for the whole period of anti-TB treatment.

Possible side-effects of the anti-TB drugs and their management are listed in Table 14.6.

| Side-effects | Drugs | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|

(a) Minor (continue anti-TB drugs) | Decreased appetite, nausea, abdominal pain | rifampicin pyrazinamide | Give tablets with small meals or last thing at night |

| Joint pains | pyrazinamide | Aspirin | |

| Burning sensation in the feet | isoniazid | Pyridoxine 100 mg daily | |

| Orange/red urine | rifampicin | Reassurance; symptom is harmless | |

| Itching, skin rash | streptomycin; rifampicin or isoniazid | Refer to higher health facility where TB treatment is available | |

(b) Major (stop the drug(s) responsible) | Deafness | streptomycin | Refer to higher health facility where TB treatment is available |

| Dizziness (vertigo, imbalance and loss of balance) | streptomycin | Refer to higher health facility where TB treatment is available | |

| Yellowish discoloration of the eye (hepatitis) | most anti-TB drugs | Refer to higher health facility where TB treatment is available | |

| Vomiting and confusion | most anti-TB drugs | Refer to higher health facility where TB treatment is available | |

| Visual impairment | ethambutol | Refer to higher health facility where TB treatment is available | |

| Shock, skin rash and decreased urine output | rifampicin | Refer to higher health facility where TB treatment is available | |

In the next study session we turn to the subject of following-up patients and tracing patients who are not taking their medication.

Summary of Study Session 14

In Study Session 14, you have learned that:

- Sputum examination should be done for all persons suspected of TB who are able to produce sputum; other diagnostic methods (chest X-ray, TB culture) support sputum examination but cannot replace it as the primary tool used for TB diagnosis.

- Treatment for TB consists of the intensive phase (two to three months) followed by the continuation phase (four to six months). Treatment involves a combination of drugs.

- If anti-TB drugs are taken incorrectly or irregularly, the patient will not be cured and drug-resistance may develop.

- Health workers have to take an active role in ensuring that every TB patient takes the recommended drugs, in the right combinations, on the correct schedule, for the appropriate periods of time.

- Anti-TB drugs are given under DOTS for the first two months for Category I and III patients, and for the whole course for re-treatment cases.

- If a patient has major side-effects related to the anti-TB drugs, refer the patient to a clinician or hospital. If the patient has minor side-effects, reassure the patient and give advice on how to relieve the symptoms.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 14

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 14.1 (tests Learning Outcome 14.1)

What are the phases of anti-TB treatment and how do they differ from each other?

Answer

There are two phases in TB treatment: the intensive phase and the continuation phase. During the intensive phase the patient took anti-TB drugs in front of you, or another health professional, or another treatment supporter. While in the continuation phase, the patient collects their medication monthly and you check that timely collection and adherence to treatment is occurring.

SAQ 14.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 14.1 and 14.2)

A 54-year-old farmer came to the health centre complaining of a cough that had lasted for over three weeks and produced whitish sputum. He also complained of low grade fever, drenching night sweat, marked loss of weight and decreased appetite.

- a.How would you classify this farmer, and what would you do for him?

- b.What additional test would you advise?

Answer

- a.This patient has symptoms of TB and is therefore a TB suspect and in need of investigation for TB. So you should refer this patient for sputum smear examination to a TB treatment facility.

- b.This patient also needs counselling for HIV testing, since there is significant overlap between these two diseases and HIV is one of the major risk factors for a patient to develop TB disease.

SAQ 14.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 14.1, 14.3 and 14.4)

W/r Almaz had experienced a cough with bloody sputum for one month; she was seen at a health centre and sputum examination showed positive for TB bacteria. She had no previous history of TB treatment.

- a.How do you classify W/r Almaz based on the smear result?

- b.Which type of patient is she (new, relapse, treatment failure, etc)?

- c.What category of treatment is needed for this patient and what is the correct treatment regimen?

Answer

- a.W/r Almaz should be classified as ‘smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis’.

- b.This patient is categorised as ‘new’ since there is no previous treatment for TB.

- c.This patient is put under ‘Category I’ and treated with the following regimen:

- Initial phase 2 (HRZE/S)

- Continuation phase 4 (HR) or 6 (HE).

SAQ 14.4 (tests Learning Outcome 14.5)

A 34-year-old female was diagnosed by sputum examination to have pulmonary TB and started on anti-TB drugs two weeks ago. She noticed reddish discoloration of her urine, but has had no other symptoms for one week. She was worried and came to you.

- a.What do you think is the most likely cause of discoloration of the urine in this patient?

- b.What advice would you give her?

Answer

- a.The most likely cause in this patient is related to rifampicin, since this drug can cause reddish discoloration of urine.

- b.Reassure the patient that this causes no harm; the patient should be advised to continue her medication.