The Ancient Olympics: Bridging past and present

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 26 April 2024, 10:27 AM

The Ancient Olympics: Bridging past and present

Introduction

Our modern Games and the Ancient Olympics are different in many respects – today’s Olympics are strictly secular, whilst the Ancient Olympics were steeped in religion; our modern Games have 42 disciplines, compared to the six of the Classical world; today, men and women of all nationalities are invited to compete, whilst, according to the Greek author Pausanias (V.6.7-8), any woman of marriageable age discovered at the Ancient Olympic festival supposedly risked being thrown off a cliff; today athletes wear light clothes (often emblazoned with their nation’s flag), whilst Ancient Greek athletes competed – and trained – completely naked.

Clearly things have changed in some respects, but a series of underlying principles and values inherited from Ancient Greece are still central to the modern Olympic spirit. For example, the London 2012 theme of ‘truce’echoed the Ancient Olympic tradition of ekecheiria (sacred peace); Classical ideals of equality and self-improvement still motivate athletes to compete fairly and push themselves to the limit; the Rio theme song, ‘The Gods of Olympus visit Rio de Janeiro’, includes references to Poseidon, Hermes, Dionysus, Aphrodite, Apollo, Hercules, Artemis, Hephaestus and Zeus; and modern programmes such as the Rio 2016 Culture Festival remind us of Classical associations between sport, poetry, music, and prose composition.

This course highlights the similarities and differences between our modern Games and the Ancient Olympics and explores why today, as we prepare for Rio's 2016 Olympics, we still look back at the Classical world for meaning and inspiration.

Please note that within this course, animations of athletes contain scenes of nudity in order to give a more realistic representation of the Ancient Olympic games.

Find out more about studying with The Open University by visiting our online prospectus

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

show an awareness of the main similarities and differences between the modern Olympics and the Ancient Greek Games

assess the ethical, philosophical and cultural importance of the Olympics to the Ancient Greek World

understand the dual role of Olympia as a religious sanctuary and the location of the Ancient Olympic Games.

1 Historical influences

In the late 19th century, inspired by German excavations in Olympia and the introduction of Physical Education programmes in schools, the French baron Pierre de Coubertin campaigned for the revival of the Olympics. The Ancient Games had been banned in the 390s CE by Theodosius I (along with all other expressions of non-Christian cults), and, except for a few re-creations dotted through history (e.g. events held at the Hippodrome of Constantinople during the Byzantine period, the outlandish Cotswold Games of the 17th century or the Wenlock Games of the mid-19th century), the Olympic spirit had remained largely dormant.

De Coubertin’s efforts to stage a modern Olympic Games were initially met with apathy and limited success. However, after a passionate campaign (which included extravagant banquets and thrilling torch-lit spectacles), he obtained the approval of King George I of Greece to bring the Games back to life in 1896. From the outset, de Coubertin adopted the Ancient Greek Games and their underlying ideals as the main inspiration for his Olympic revival. For example, he was an ardent believer in the Classical principle of a healthy mind in a healthy body, so he ensured that the rules drafted by the International Olympic Committee (which would become the text of the Olympic Charter) reflected an emphasis on moral values and a concern with virtue and discipline as well as physical achievements. Promoting global peace (a modern ‘Olympian truce’) was also at the heart of the modern Olympic movement. Like the Ancient Greek Games, the first modern Olympics insisted on the principle of amateurism. (The participation of professional athletes was perceived as a threat to the Olympic ideals of fairness and equal opportunity, although, in practice, this measure simply exacerbated the unfairness and social inequality of the Victorian period, since only the richer gentlemen of leisure could afford the time and expense of taking part in the Games.) The athletic events of the 1896 Olympics were also combined with parallel spectacles of art, music, poetry and architecture, like the Ancient Games. De Coubertin himself would later admit that these spectacles were perhaps a weaker aspect of the first modern Olympics, which, ironically, is probably not far removed from the opinions of some Ancient Greek spectators – Pausanias (X.9.2), for instance, describes the musical competitions of the Pythian Games as ‘scarcely worthy of serious attention’.

The first modern Olympics were held in Athens rather than their original site of Olympia, partly for political reasons (Athens was now the capital of the recently established Greek nation) and partly due to the availability of infrastructure. A relatively small number of participants attended these Games and the quality of the athletes was variable to say the least, but, crucially, the event planted the seed of the Olympic revival and initiated a process that has led to the forging of the Modern Games that we know today. Since 1896, the modern Olympics have been held every four years (except 1916, 1940 and 1944). They have become a truly global event, and, although many aspects have changed since their inception in Ancient Greece (and continue to change as the Games are adapted to the 21st century), the underlying Classical ideals of peace, self-improvement, equality and mutual respect still resonate. By espousing and promoting these ideals, the Olympics act as a bridge between the past and our present.

Figure 1 This medal from the 1896 Olympics illustrates the conscious associations between the revived Olympics and the Ancient Greek Games. The obverse (left) shows the Athenian Acropolis and Parthenon. The reverse (right) shows Zeus holding a globe, upon which stands the goddess of victory (Nike) brandishing a wild olive branch.

2 What are the Ancient Olympics?

According to ancient scholars, the first ever Olympic Games were held in 776 BCE at the site of Olympia (in the district of Elis, on the Peloponnesian peninsula). This date was worked out by totting up the years from an early document that recorded Olympic victors. In fact, the roots of the Olympic festival probably stretch even further back in time to the Greek Bronze Age. Archaeological finds provide evidence of early manifestations of sporting events among the Mycenaeans and Minoans in the second millennium BCE, and there is a long literary tradition (particularly of Homeric texts) linking the development of Greek athletic festivals with funerary rituals that commemorated the deaths of local and mythological heroes (such as Pelops and Patroclus) whose funeral is related in Book 23 of Homer’s Iliad.

From the 8th century BCE onwards, the Ancient Games were held every four years in Olympia. This quadrennial cycle was known as an Olympiad, and it became such a cultural landmark that long periods of time were often measured in ‘Olympiads’, i.e. four-year units, by Ancient Greeks. Recent research suggests that the intriguing Antikythera mechanism (a complex clockwork device from the 2nd century BCE that has baffled archaeologists for over a century) may have originally been used partly as an Olympiad calendar.

Figure 2 The Antikythera mechanism, dubbed the world’s earliest computer, was found by sponge divers in 1901 at the bottom of the Ionian sea. One of its uses may have been to calculate the relation between Olympiads and the starting dates of other Ancient Greek athletic events.

The Ancient Olympics were, of course, a sporting event, but there was much more to it than that. Athletics were intertwined with most aspects of life and society in Ancient Greece, including religion, art, identity, politics, law and literature. This relation can be seen, for example, in the large number of athletic scenes decorating the ubiquitous black and red figure Athenian vases; the abundance of references to athletic traditions found in classical mythology; the sports-related metaphors of Plato’s philosophical texts; and the combination of altars, temples, accommodation for high-status officials, monuments, treasuries, banqueting facilities and sporting grounds found at the site of Ancient Olympia. By the 6th century BCE, a Hellenic cultural identity had come into full existence, and the Games played an important role in underpinning this identity across the Greek world.

Interactive presentation

The following interactive presentation displays a series of literary quotes relative to the impact of the Olympics in Greek and Roman culture.

Participation in the Ancient Olympics was limited to free Greek male amateur sportsmen (Herodotus V.22.2). Non-Greeks, slaves, people accused of murder or blasphemy, and women (with some rare exceptions), were not allowed to compete. This might seem restrictive by modern Olympic standards. However, these regulations did not put off scores of people from flocking to Olympia to watch the Games, travelling from all over the Greek city-states and colonies as far afield as Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. At its height, the Ancient Olympic festival probably hosted over forty thousand people. According to tradition, it was believed that all these athletes and spectators were able to travel safely to Olympia under the protection offered by a sacred truce (the ekecheiria), proclaimed before the start of the Game by the spondophoroi (truce-bearing heralds who took the message of peace to various regions of Greece).

It is reputed that the Olympic sacred truce dates back to 884 BCE, when Iphitos (king of of Elis), the lawgiver Lycurgus of Sparta and Cleosthenes (archon of Pisa) followed the advice of the Delphic oracle and signed a pact to put an end to local disputes, which were interrupting worship at Olympia. The terms of this pact were engraved on a bronze disc, which was displayed for centuries in the Temple of Hera at Olympia, and became adopted as part of the Ancient Olympic tradition. Although a truce was ceremonially proclaimed before the start of each Olympic Game, in practice this did not always stop all conflicts. For example, in 424 BCE, the Spartans threatened to invade Olympia; in 365 BCE, the sacred grove was shockingly occupied by Arcadians and Pisatans while the Games were in full swing, and in 312 BCE Macedonians raided Olympia and plundered the treasuries. The situation was therefore not too dissimilar from some of our modern Games, which celebrate peace and embrace the theme of truce but, in reality, do not stop armed conflicts from being fought in various parts of the world.

Interactive presentation

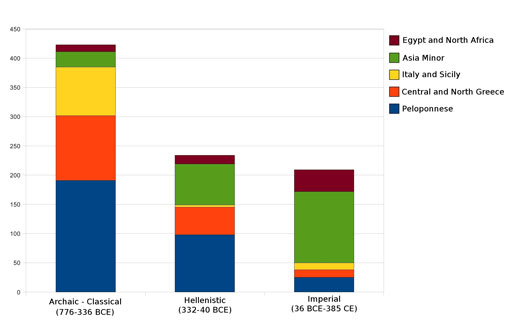

This interactive presentation will give you an illustration of the geographical diversity of the Ancient Olympic athletes. The earliest victors came primarily from mainland Greece and the Greek cities of Sicily and Southern Italy. However, areas such as Asia Minor and Egypt eventually came to dominate the victory lists in later periods. If you would like to explore more interrelations between these and other regions of the Ancient world, have a look at the HESTIA project.

Figure 3 Graph illustrating the geographical diversity of Ancient Olympic athletes

In addition to their athletes, Greek communities sent sacred ambassadors (theoroi) as their official representatives to the Ancient Olympics. Theoroi were roughly similar to our modern diplomats. The coming together of theoroi united the Greek community, albeit temporarily. Their mission (i.e. their theoria), was a sort of pilgrimage. Theoria literally means ‘watching’ or ‘spectacle’ (from the same root as English ‘theatre’), a term which expresses their responsibility to watch the festival events on behalf of their community. As well as witnessing the festival, theoroi liaised with local leaders, represented their state in the official procession and sacrifice, and carried out a further sacrifice on behalf of their community. They also looked after the interests of their state’s athletes if any difficulties arose. Theoroi wore special wreaths (as the hero Theseus does in Euripides’s 5th century BCE play Hippolytus, lines 798-810; these showed that they were on sacred business and should not be harmed.

The Ancient Olympics lasted for over a millennium (from the 8th century BCE to the 4th century CE). This is, by most measures, a staggering amount of time for any festival to persist. During this period, the Games evolved from unofficial athletic rituals in the Dark Ages to a well-established quadrennial festival in the Classical period, developing later into a Romanised spectacle that would eventually degenerate into gladiatorial contests. The Olympics were constantly readapted to each period, with different durations, events and regulations. This course will focus principally on the Ancient Olympics at their zenith, around the 5th century BCE. However, as you make your way through the material in the following pages, try to bear in mind the duration of the Ancient Olympics and consider the ways in which the Games changed through time.

Interactive presentation

This interactive presentation shows how the Ancient Olympic Games evolved over time.

2.1 Further resources

Reading

Anderson, D. (2000) The Story of the Olympics. New York, Harper Collins.

Finley, M.I., & Pleket, H.W. (1976) The Olympic Games: the first thousand years. New York, Viking Press.

Paleologos, C. (1976) The Ancient Olympic Games, in Killanin, L. & Rodda, J. (Eds.), The Olympic Games (pp. 24-26). New York, Macmillan.

Web links

3 The broader context: Other athletic festivals in Ancient Greece

Olympia was not the only place to host sporting games in Ancient Greece. The Greeks were passionate about athletic festivals, and different cultural manifestations of the athletic spirit could be found in many regions of the Hellenic world. In the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, as the influence and cultural impact of the Olympics were consolidated, other major athletic festivals began to emerge, each held at a different location under the patronage of one of the Greek gods. Three of the more important festivals were the Isthmian Games (named after the Isthmus of Corinth, held in honour of Poseidon, the Nemean Games (held at Nemea in honour of Zeus) and the Pythian Games (held at Delphi in honour of Apollo).

These three major festivals, along with the Olympics, are collectively known as the Panhellenic (i.e. all-Greek) Games, in reference to the breadth and depth of their cultural impact within the Greek world. They were also referred to in Ancient Greece as the Periodos (i.e. circuit) Games, because their starting dates were organised in a way that avoided clashing with each other, thereby allowing athletes, as well as the more avid spectators, to attend a different game every year if they wished to. The Nemean and Isthmian Games were held both the year before and the year after the Olympic Games; the Pythian Games were held between the Nemean and Isthmian Games (on the third year of each Olympiad cycle).

| Year 1 | Olympics (July - August) |

| Year 2 | Nemean (July - August) |

| Isthmian (April - May) | |

| Year 3 | Pythian (July - August) |

| Year 4 | Olympics (July - August) |

| Year 5 | Nemean (July - August) |

| Isthmian (April - May) | |

| Year 6 | Pythian (July - August) |

Footnotes

The Panhellenic cycle. Note that July and August come before April and May. This is because the Attic calendar started after the summer solstice. July – August was their first month, which was called Hekatombaion.The Panathenaic Games, held in Athens every four years, were also grand in scale and culturally significant. However, they were not considered a Panhellenic festival. They were sporting events held as part of the local Panathenaia religious celebrations, which were organised in honour of the city’s patron goddess, Athena. The Panathenaic Games were distinctive in that athletic victors were awarded emblematic large vessels (known as Panathenaic amphorae) full of olive oil, which was a valuable commodity. The Heraean Games also had a very distinctive aspect; only virgin females could compete. These games were held at Olympia in honour of Hera (Zeus’s wife). Victors were awarded a wreath of wild olive and given the privilege of setting up their effigy in the Temple of Hera (within the sacred grove of Olympia).

By the Hellenistic period, hundreds of other minor sporting events were dotted across the Greek world. These smaller festivals (e.g. the Soteria Games of the Aetolians, the Sebasteia Games of Judaea or the Nikephoria Games of King Eumenes II of Pergamon (one of his letters can be seen here)) varied significantly in structure, ethos and duration. For most of Ancient Greek history, they were eclipsed by the cultural impact and significance of the Olympics, which were by far the largest and most popular athletic festival. However, these minor sporting events played an important role during the later Roman period, when the Games were banned by Theodosius I. Because they were less prominent and more geographically spread out, they were harder to suppress and therefore succeeded in keeping the ancient athletic spirit alive for some time, years after the Olympics had ceased to be.

Interactive presentation

This interactive presentation will give you the locations and details of the Panhellenic, Panathenaic and Heraean Games.

3.1 Further resources

Reading

Miller, S. (2006) Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven, Yale University Press.

Miller, S. (1992) Nemea: A Guide to the Site and Museum. University of California Press.

Weir, R. (2004) Roman Delphi and its Pythian Games. Oxford, British Archaeological Reports International Series.

Web links

4 Preparing for the games: Training body and mind

The preparations of an ancient Olympic athlete started many months, even years, before the opening of the festival, in the gymnasion. The Ancient Greek gymnasion was a public location used for training, education, exercise and socialising – something roughly similar to our modern community centre. In Ancient Greek society, achieving a harmonious balance between body and mind was an important aspect of an individual’s personal development. The gymnasion therefore hosted wrestling matches as well as music rehearsals and provided weight lifting training as easily as philosophy lectures.

Animation 1 Ancient Greek athletes training for the Olympics

This broad conception of the education process was known as kalokagathia, from kalos k’agathos, meaning ‘beautiful and good’, or as the Roman poet Juvenal later put it in one of his tongue-in-cheek satires, ‘a sound mind in a sound body’ (X.356). Olympic athletes were expected to adhere to this guiding principle by demonstrating not just physical prowess but also virtue, loyalty, valour, attitudes of self-improvement and moral responsibility. The combination of skill, strength and ethical behaviour was referred to as arete (which could be loosely translated as ‘excellence’), and it was the role of the gymnastes (the coach) to instil this sense of responsibility in the athletes as part of the training process.

How does that sound to you?: the apoxyomenos

Figure 4 Before starting their training or competition, Ancient Greek athletes rubbed oil from a small jar (an aryballos, like the one above) onto their skin. After exercise, they washed the oil, dust and sweat off their bodies using a sponge, water and a curved metallic tool called a stlengis. ‘Apoxyomenos’ was the word used to refer to the person who cleaned himself in this manner.

The word gymnasion comes from gymnos, which means ‘naked’. Some athletes wore a perizoma (loincloth) or, very occasionally, tied up their genitals with a strap called kynodesma, but by and large they trained and competed completely naked. There has been a lot of speculation as to why and how this tradition, which probably started in the 6th century BCE, developed. Ease of movement when competing and an aesthetic appreciation of the naked male body probably played a role. However, there is also a deeper philosophical and moral dimension – nakedness emphasised equality. By stripping athletes of their material signs of status (be it the most expensive gowns or the poorest rags), equal treatment was encouraged. Competitors were left with little more than their mind and body, so their performance was seen as a result of the skills that emanated directly from their person rather than their circumstances. For this same reason, Ancient Olympic athletes were, in principle, expected to be amateurs rather than professional sportsmen (professionalism was seen as an unfair advantage over those who could not afford the luxury of full-time training). This principle of equality was called isonomia, and it had far reaching implications across diverse areas of Ancient Greek culture (most notably in the development of Athenian democracy).

So what’s the difference?

The modern gym and the Ancient gymnasion

Figure 5 Left image: people training in a modern gym. Right image: scene from an Ancient Greek gymnasion (Berlin Staatliche Museen, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Antikensammlung inv. no. F2180).

What do you think are the main differences between the modern gym and the Ancient Greek gymnasion in terms of the activities, training regimes and motivations of their users? Once you have come up with a few ideas, click on ‘reveal comment’ to read some of our suggestions.

Comment

The Ancient Greek gymnasion was, in many ways, an inspiring and nurturing environment. However, in certain respects, it could also be considered harsh, restrictive and alienating when compared to our modern gyms. The extracts used here to illustrate the similarities and differences between modern gyms and Ancient Greek gymnasia are from the ‘Gymnasium law of Beroia’ – a set of rules inscribed on the wall of a gymnasion in the Macedonian city of Beroia in the 2nd century BCE.

According to the Gymnasium law of Beroia, ‘none of the following may enter the gymnasion and strip for exercise: a slave, a freedman or one of their sons, a man who is incapable of physical training, a man who has prostituted himself, a man who works in commerce, a man who is drunk, a madman. If the gymnasiarch (i.e. the head of the gymnasion) knowingly allows one of these men to oil himself, or continues to allow it after someone has reported this and pointed it out to him, he shall pay a fine of 1000 drachmas...’.

These limitations might strike us as unnecessarily alienating from a modern point of view. This is perhaps because we are used to most modern high street gyms being run by private companies as commercial enterprises. Their main aim is to make a profit and, therefore, they are generally open to any member of the public who can afford the fees, regardless of gender, chastity or devoutness. The Ancient Greek gymnasion, on the other hand, was funded – and in some cases administered – by wealthy benefactors (gymnasiarchs) who received honour from their cities in return for that service.

The Ancient Greek gymnasion was principally a place of physical and mental development, where ethical values and intellectual qualities were inculcated to the young. This was called ephebeia (a system by which men aged between 17 and 19 received physical education in all Greek cities). In addition, according to the Gymnasium law of Beroia, ‘the ephebes [i.e. adolescent males] and those less than 22 years of age are to train in spear-throwing and archery every day…’, which served as a form of military training. Therefore, setting a right example and creating a propitious learning environment was crucial. The gymnasion also played an important role in the preparations for athletic festivals and, as a result of this, had a religious dimension that modern gyms clearly do not have.

Today, gyms are not generally thought of as a venue for formal education – their main emphasis is on sporting and health. However, there still are some links between pedagogy and modern gyms. For instance, many schools contain gyms, where Physical Education classes are imparted as part of a child’s development. In addition, many commercial high street gyms offer training that goes well beyond weightlifting and pedalling (e.g. yoga, martial arts or Tai Chi).

Finally, it could be said that Ancient Greece put the ‘physical’ into Physical Education in more ways than one. Ancient Greek athletes exercised naked, covered in olive oil. Homosexual encounters between older men and younger boys were not uncommon in the gymnasion. By comparison, the clothed, chaste exercising of modern high street gyms sets a very different tone!

The Panhellenic Games are also referred to sometimes as the Stephanitic Games (from stephanos, meaning ‘crown’ or ‘garland’). This is because none of the athletic victors in these festivals received direct financial rewards – they trained and competed, in principle, for glory (kleos) and to honour the gods. Ancient Olympic victors were awarded a wreath of wild olive, a wreath of wild celery at the Nemean Games, a wreath of pine at the Isthmian Games and a wreath of laurel at the Pythian Games. These awards had no material value in themselves. However, they symbolised the glory achieved by the victor – a priceless, intangible reward. The concept of kleos was engrained in an athlete’s training process from the word go. It was considered his principal motivation and reflected a profoundly Greek cultural understanding of ethics.

Box 1 Highlight: glory in ancient thought – and modern

Sport, rock and roll, Hollywood stardom, politics, even war, can all be ways of aiming at glory. The idea of glory (kleos), and in particular sporting glory, is pervasive in the ancient world. A whole book (23) of Homer’s Iliad is devoted to Patroclus’s funeral games (and the rest of the Iliad is about the glory - and the horror - of war). Most of Pindar’s poetic work is about celebrating athletic triumphs. Plato tells us, at Symposium 174a, of how the crowds flocked to fete the poet Agathon when he won an Athenian dramatic prize. Chariot-racing was still causing riots in Byzantium up to its fall to the Turks. Thucydides has Pericles saying in his ‘funeral oration’ that the Athenian warriors ‘thought it more beautiful to stand firm and die, rather than to fly and save their lives; they ran away from the word of dishonour, but on the battlefield their feet stood fast, and in an instant, at the height of their fortune, they passed away from the scene, not of their fear, but of their glory’ (Thucydides, Histories 2.42).

Greek ethicists thought that glory was part of what makes a good life, and so something that was ethically important: one of the virtues listed by Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics (IV.2) is the virtue of magnificence, putting on a spectacular show. But modern ethicists usually have little to say about glory. Partly because of the influence of philosophers like Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), they usually say only what Arthur Adkins said in a famous study of Greek ethical concepts, namely that glory cannot be an important idea for us: “For any man brought up in a western democratic society… duty and responsibility are the central concepts of ethics… in this respect we are all Kantians now” (Adkins 1960, 2).

One contemporary philosopher who suspects there is a gap here between what we really think about ethics, and what we only think we think about ethics, is The Open University’s own Timothy Chappell. He argues that in practice our ethical beliefs about glory are much closer to the ancient Greeks’ than the most typical products of modern moral philosophy suggest. That might be a reason for reforming either our beliefs about glory, or the way we do moral philosophy. Chappell suggests it is the latter. You can read more about his views in his article, Glory as an ethical idea.

Although in principle, glory, equality and self-improvement were the driving force behind the Ancient Olympic spirit, of course, reality was not always rosy in Olympia. The noble goals of excellence and virtue were not always the athletes’ main priority and the idealistic principles of equality and fairness were not always adhered to by judges and organisers. Just like the modern Games, the Ancient Olympic Games had their fair share of scandals, bribes, accusations of corruption and other irregularities. Many Ancient Greek athletes were de facto professionals rather than keen amateurs. Much like the 1896 Games (which, in practice, priced out anyone who was not a gentleman of leisure), in the Ancient Olympics only wealthy people could afford to foot the bills of a long training regime and cover the costs of travelling to Olympia in order to compete as athletes. What is more, despite the fact that cheating was considered disgraceful and insulting to the gods, several ancient authors suggest that it was not entirely uncommon.

Video: Roger Bannister

Sir Roger Bannister, the first athlete to run a recorded mile in less than four minutes in 1954, discusses the links between modern ethics in sports and Ancient Olympic values.

The figure of the Hellanodikes was central in trying to prevent these cases of foul play. The Hellanodikai (literally ‘judges of Greece') were a cross between our modern referees and the Olympic Organising Committee. They were in charge of upholding the rules, organising the Games, maintaining standards, dividing contestants into age categories and participating in some of the ceremonial acts (e.g. the procession that opened the Games and the awards ceremony). The Hellanodikai (ten in total from the 4th century BCE onwards) were elected every Olympiad from the citizens of Elis (a nearby town). Their role started months before the Games opened, supervising the training of the athletes and making sure that nobody who wasn't allowed to tried to participate in a competition. If athletes were discovered breaking any of the rules, the Hellanodikai would be entitled to use their rhabdos (a long stick) on them. For more serious cases of bribery, blackmail or match fixing, fines were imposed. The money raised by these fines was normally used to commission Zanes statues (bronze sculptures of Zeus displayed in the Altis area of Olympia). People who saw these statues would know that they represented the embarrassment and disappointment that came with being discovered cheating. The name and city of the cheating athlete were engraved on the statue's base, so the embarrassment of his corruption would live long past the athlete's lifetime and act as warning to future generations.

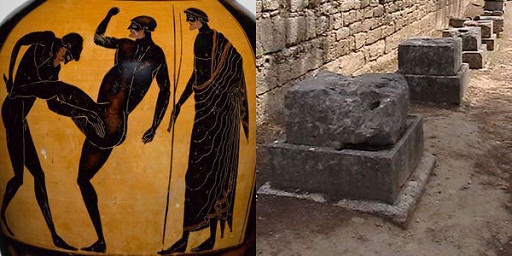

Figure 6 Left: a Hellanodikes (right) holding a rhabdos whilst refereeing a wrestling match (6th century BCE Panathenaic amphora), Metropolitan Museum, inv. no. 16.71. Right: bases of Zanes statues in the Altis area of Olympia. The statues that once stood on these bases were paid for by fines imposed on cheating athletes.

4.1 Further resources

Reading

Adkins, A. (1960) Merit and Responsibility. Oxford, Clarendon.

Chappell, T. “Glory as an ethical idea”. Philosophical Investigations 34 (April 2011), 105-134.

Miller, S. (2004) Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources. University of California Press.

Reid, H. (2011) Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World: Contests of Virtue (Ethics and Sport). London, Routledge.

Young, D. (1984) The Olympic myth of Greek amateur athletics. Chicago: Ares.

Web links

5 Day One: The opening ceremony (athletics and religion)

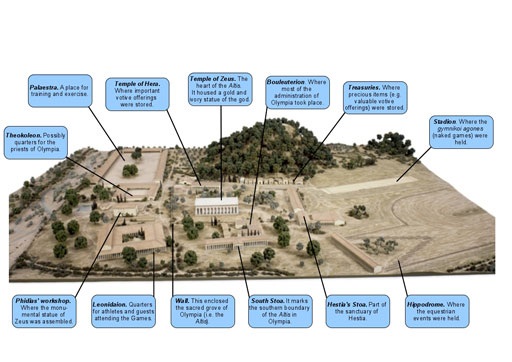

The Ancient Olympics were, in essence, a religious festival. The Games were held in honour of the god Zeus and almost all aspects of the athletic events and the rituals that surrounded them were connected with the realm of the sacred to some degree. This Olympic association between athletics and religion was made clear from the outset – the first day of the Games was dedicated principally to religious ceremonies. This level of devoutness, which might strike us as unusual compared to the secularity of modern Olympism, could be explained partly by the fact that Olympia had never been a city in the traditional sense – it was half sanctuary, half sports grounds compound. The site of Olympia was broadly divided into two sections by a large wall – the area where the athletic spectacles took place, and the Altis, or the sacred grove, where temples, halls, altars and the treasuries were located.

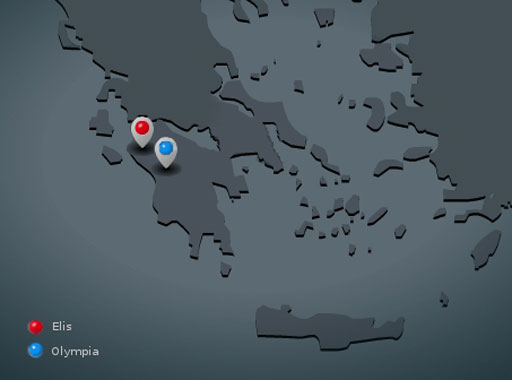

Figure 7 Model of the site of Olympia (British Museum) with the function of some its more important structures listed

When the Games were not being held, only a handful of officials and priests lived in Olympia. Most of the people who controlled and supervised the Games lived in the nearby town of Elis. In fact, the religious ceremony that opened the Olympic festival started in Elis, rather than Olympia itself. A large group of several hundred athletes, who would have gathered in Elis several months earlier in order to complete their training under the supervision of the ten Hellanodikai, began marching towards Olympia the morning before the start of the Games. They were accompanied by their families and entourage, the Hellanodikai, the fifty members of the Olympic council and the horses and chariots of the equestrian events. This mighty procession took one day and one night to cover the 36 kilometres that separate Elis from Olympia.

Figure 8 Locations of Elis and Olympia

Just before arriving, they stopped at the Pierian spring, a sacred site where the Hellanodikai were sprinkled with the blood of a sacrificed boar and washed in the spring’s waters. Purified by this ritual, they proceeded towards Olympia. A massive crowd waited for them there – thousands of spectators, traders, magicians, peddlers, scholars trying to spread their philosophies, lawyers, painters and sculptors displaying their works. According to Epicteus (I.6.23-29), writing in the 1st century CE, the noise and activity were overwhelming. When they arrived at Olympia, the Hellanodikai and athletes made their way to the Bouleuterion (council house). There, athletes would be classified into age groups (in order to ensure a fair competition) and give an oath in front of the statue of Zeus that they would commit no evil act during the Games. They would then proceed to one of the many altars in the sacred grove, where they would make an offering to Zeus, Hermes, Apollo or Hercules and pray for victory.

Box 2 Highlight: Hercules and Pelops – founding heroes

The foundation of the Olympic Games is usually attributed to one or both of the heroes Hercules and Pelops. The Hercules tradition goes back at least as far as the early 5th century BCE, when Pindar’s victory ode Olympian 10 (476 BCE) tells how Hercules laid out the sanctuary and ‘established the four years’ festival with the first Olympic games and its victories’ (ll.55-9), after successfully cleaning the stables of the local King Augeias. Lysias’s Olympic Oration 33 (written around 400 BCE) asserts that Hercules envisaged the games as conducive to ‘mutual friendship amongst the Greeks’.

The Pelops tradition also first appears in an ode by Pindar of 476 BCE (Olympian 1.93-6), which tells the story of his chariot-race against the Elean king Oinomaos for his daughter Hippodameia’s hand, and concludes with mention of the ongoing fame of the contests on the racecourse of Pelops. Hippodameia is supposed to have established the girls’ games of Hera’s Olympian festival in thanksgiving for her marriage (Pausanias 5.16.4).

Both heroes’ victories were celebrated in sculpture decorating the Temple of Zeus. Pelops’s chariot-race was prominently featured in the east pediment, over the entrance, while metopes depicting the twelve labours of Hercules were placed within the east and west porches. The Pelops story may have provided inspiration especially for charioteers, but the muscular Hercules is clearly a role model for all aspiring athletes. Sacrifices were regularly made to Pelops at his shrine within an ancient enclosed grove near Temple of Zeus, and to Hercules at an altar supposedly founded by the king Iphitos who re-instituted the Games in 776 BCE (Pausanias 5.4.6 and 5.14.9).

Figure 9 Metope from the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, depicting Hercules and the Cretan bull

5.1 Further resources

Reading

Miller, D. (1969) Gods and Games: Toward a Theology of Play. New York and Cleveland. World Publishing.

Sinn, U. and Thornton, T. (trans) (2000) Olympia: Cult, Sport and Ancient Festival. Princeton, Markus Wiener.

Stafford, E. (2011) Herakles (Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World). London, Routledge.

Valavanis, P. (2004) Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece. Los Angeles, Getty Publications.

Yalouris, N. (1976) Olympia: Altis and Museum. Zurich, Verlag Schnell & Steiner Munchen.

Web links

6 Day Two: The equestrian events and pentathlon

Day two was dedicated to equestrian events and the pentathlon. Horse owners would have spent the previous evening tending to their animals and making sacrifices to appease evil spirits; athletes would have started the day by marching in procession from the Altis to the sporting grounds in Olympia; and spectators were by now looking forward to the start of the sporting events – the hippikoi agones and gymnikoi agones (equestrian and naked games).

6.1 Equestrian Events

The equestrian events opened the sporting competitions in the Ancient Olympics. Compared to the simplicity of the athletic events, the equestrian races were flamboyant and ostentatious. Impressive racing horses and expensive chariots were paraded in front of spectators, and some prominent citizens used the event as an opportunity to flaunt their wealth and status. Chariot entries were sometimes sponsored by states rather than individuals, which was unheard of for other Ancient Olympic disciplines, and some competitors entered more than one chariot in an attempt to increase their chances of winning. For example, according to Thucydides (VI.18.16), the extravagant Alcibiades entered as many as seven chariots into the same race, winning first, second and fourth prize simultaneously.

Equestrian events were also unusual in that they were the only discipline that allowed adult women to compete. This was due to the fact that the owners of the chariots and horses were regarded as the real competitors in the event, rather than the riders or charioteers (who were frequently anonymous slaves or hired professionals). Therefore, as long as a female contestant entered the competition as an owner, this was considered to be within the rules. Before the start of the races, the Hellanodikai classified the horses into age groups in order to ensure fairness and equality (but there were no group divisions for jockeys or chariot drivers).

Equestrian events took place in the hippodrome, a large oval arena constructed to the east of the Altis and to the south of the stadion Although the location of the hippodrome was identified in 2008 thanks to geophysical survey techniques, no archaeological remains have been uncovered yet, so most of what we know about it is based on interpretations of ancient texts. It is believed that two large pillars stood at either end of the racing track to mark the turns (which were the most dangerous parts of the course). Races started in a dramatic staggered sequence, using a mechanism called the hippaphesis. This involved arranging the contestants in a prow formation and allowing the two individuals at the very back to start first, followed by the ones immediately in front of them, and so on until all competitors formed a straight line. At that precise point, a trumpet was blown and the race officially began.

Animation 2 tethrippon race

The first equestrian race to be held on the second day of the Olympics was the four-horse chariot (the tethrippon), which was the fastest and most dangerous of all. This was followed by the horseback races (the kele), which were roughly similar to modern horse races except that jockeys rode without stirrups. Next came the two-chariot race. During the 5th century BCE, two other equestrian events were held at the hippodrome – the apene (a mule-cart race) and the kalpe (a competition in which, apparently, jockeys had to complete the last lap by foot); however, these events were probably not very popular, as they disappeared relatively quickly. Towards the end of the 4th century BCE, a four-foal chariot race was added. The length of the races was 12 laps around the track (i.e. approximately nine miles) for the chariots and six laps (i.e. approximately four and a half miles) for horseback races.

So what’s the difference?: wheel designs: modern bicycles and Ancient Greek tethrippa

Figure 10 Left image: modern Olympic cyclist Victoria Pendleton. Right image: A tethrippon charioteer depicted on a black figure amphora from the Circle of Leagros, 6th century BCE (Harvard University Art Museum, inv. no. 1933.54).

What do you think are the main differences between modern bicycle wheels and the wheels of the Ancient Greek tethrippa? What are the factors affecting these differences? Once you have come up with a few ideas, click on ‘reveal comment’ to read some of our suggestions.

Comment

It would seem that the differences are obvious; sleek, modern and highly engineered against rough, ancient and hand crafted, but there are similarities when we look more closely. The aim is the same – to win a race using wheels and muscle power. And there lies the key technical similarity: how to get the most effective wheels? They need to be strong to survive all the loads applied to them; they need to be stiff; they need to be light. The heavier a wheel the more effort is needed to rotate it. But lightness brings the risk of reduced strength and stiffness.

The more common modern multi-spoke bicycle wheel is one of the most efficient structures ever created – its strength to weight ratio is excellent and its spokes are always kept stretched – but the large number of narrow spokes leads to air resistance as the wind circulates around each spoke and becomes turbulent (i.e. with a complex and erratic movement). This limitation moves the solution to a wheel design with four or five broad spokes. Since this is better manufactured in one piece, it requires a spoke that can take tensile and compressive (i.e. stretching and squeezing) loads.

Something the modern day Olympians share with their ancient counterparts is the solution to this spoke problem. Granted they used the natural material of wood and we use carbon fibre reinforced polymer (i.e. basically a plastic strengthened by strands of carbon), but both are examples of composite materials in that they have dissimilar materials working together. Wood has cellulose tubes with lining bonds whereas modern wheels have carbon fibres in an epoxy or polyester matrix (i.e. bonding plastic). Each provides a stiff, strong spoke which can compress without buckling but still be easy to rotate. So the wheels of the tethrippon might seem a long way from the bicycle wheels of today’s Olympics but they share a common approach – they minimise the weight, streamline the profile and maintain the strength and stiffness.

6.1.1 Further resources

Readings

Hemingway, S. (2004) The horse and jockey from Artemision: a bronze equestrian monument of the Hellenistic period. University of California Press.

Web links

6.2 Pentathlon

The pentathlon closed the sporting spectacles of the second day in the Ancient Olympics. In Classical Greek, pentathlon means 'five competitions'. These five events were the jump, discus, foot race, javelin throw and wrestling. Only one prize was awarded and each pentathlete was expected to participate in every one of the five events in order to be eligible for the award. Unlike equestrian events, the pentathlon clearly embodied the spirit of the Ancient Olympics. There was little ostentation or snobbery, and competitions were carried out with a minimal amount of paraphernalia (even the sporting grounds were stripped of any unnecessary adornments, leaving little more than a simple dug out area on the stadion surface in most cases). Pentathlon competitors required a broad range of skills in order to suceed in all five events, as well as a combination of physical prowess and psychological strength and endurance, which appealed particularly to the Ancient Greek principle of kalokagathia.

Jump

The jump event (halma), was similar to our modern version of the long jump, with some exceptions. The athletes jumped to the rhythm of music, probably played by an aulos (flute), which suggests that there may have been an element of choreography involved. They stood a short distance away from a small board (called bater) and stretched both arms out. Then they leaned back, ran forward and jumped from the board, keeping both legs together in the air, onto a shallow pit dug into the stadion surface. This pit, called the skamma, was full of loose soil (but probably not sand).

Animation 3 jump using halteres

One significant difference between the halma and the modern long jump is that Ancient Olympic athletes used a pair of weights called halteres. The halteres (which were also used as dumbbells during an athlete's training) were made of stone or metal. They could be long or spherical and did not have a standard weight. During the halma, they were carried by the jumper in front of him, thrust backward just before the jump and dropped in the descent, apparently to increase the distance of the jump. It is unclear whether the halteres really offered any physical advantage during the jump. Modern athletes have attempted to reconstruct the Ancient Olympic halma using halteres, but only worse results have been achieved with the use of weights.

Discus

Like the halma, the discus throw involved precision and rhythm as well as strength, and was probably conducted to the accompaniment of music. This athletic event was a favourite subject of Ancient Greek sculptors and vase painters, who have left us with many representations of this particular competition. Unlike the modern Olympic version, Ancient Greek discus throwers did not spin on their own axis before the throw. They started by bringing their left foot forward and shifting the weight of their body to their right side whilst holding the discus upfront with both hands at head level. With their right hand they swung the discus a few times back and forth by their side, turned their body with the movement of the swing and finally threw the discus straight ahead. It seems that the shape and weight of the discus were not standardised (although we do know that younger competitors always used a lighter version). The discuses that have been found are made of stone or metal (frequently bronze) and weigh between 2 and 2.5 kilos.

Animation 4 discus throw

Foot races

Running is the oldest known competition of the Ancient Olympics. There were four events in this discipline at Olympia: the stadion race, which consisted of a sprint of about 192 metres (i.e. one lap around the stadion); the diaulos, which translates literally as 'double flute' and consisted of a double-stadion race; the dolichos, a long race of approximately 7.5 to 9 kilometres; and the hoplitodromos, an unusual race introduced in the 6th century BCE in which athletes dressed in military armour (helmet, large shield and, originally, shin guards – weighing in total some 30 kilograms) and ran two laps around the stadion. There was no marathon race (this was only introduced in the modern Olympics). Foot races were particularly exciting spectacles for the audience, who stood on the slopes at either side of the stadion, about an arm's length from the athletes. Just like the equestrian games, a specially-designed starting mechanism was used in all foot races. It was called the hysplex, and it consisted of a set of hinged gates operated from the distance by the Hellanodikes, who would pull a cord in order to allow all runners to start simultaneously.

Figure 12 Detail of the stadion at Olympia. The stone structure in the centre of the image is a balbis (a strip of starting blocks that stretched across the surface of the stadion with a groove for the athletes to position their toes).

How does that sound to you?: the hysplex

Figure 13 The hysplex was a fence-like structure erected in front of the balbis. The design of the hysplex mechanism varied through time, but its function remained the same – acting as a physical barrier to reduce the number of false starts, which, according to Herodotus, were punished by whipping. The release of the hysplex was the equivalent of the starter's pistol in our modern Olympics.

Javelin throw

The level of success of a javelin throw was, like the discus throw and the halma, assessed on the basis of the distance achieved, but also the athlete's precision and rhythm. The javelin (akon) was thin and light and had approximately the same length as a man. It was made of wood (frequently elder wood) and had a small, sharp metallic tip. Much like its modern Olympic equivalent, the throw began with the javelin held at the athlete's shoulder level. The athlete gripped the javelin's shaft with his right hand and held the tip with the left hand. He stepped forward (there was probably no running) and then threw the javelin straight ahead as far as possible. Unlike the modern javelin throw, the Ancient Olympic akon was thrown with the use of a leather strap called an ankyle. The ankyle was wrapped around the javelin (close to its centre of gravity) and held between two of the athlete's fingers in a loop. During the last stage of the throw, the ankyle would be quickly unwrapped (which had the effect of artificially extending the athlete's arm), increasing the javelin's rotation (thus making it more stable in the air) and accelerating the projectile over a longer distance.

Animation 5 javelin throw

Wrestling

Wrestling (pale) was divided into two types in the pentathlon – orthia pale (which translates as 'upright wrestling') and kato pale (i.e. ground wrestling). The aim of orthia pale was to throw one's opponent on his hip, shoulder, or back. Three fair falls were required to win a match. Athletes started the fight in a position called systasis (i.e. 'standing together'), which involved leaning against each other with their foreheads touching. In kato pale, which was fought in a crouched position, opponents wrestled until one of them acknowledged defeat (which was signalled by holding up one's right hand with the index finger extended). Pale matches were fought in a simple, shallow pit (the skamma) dug into the surface of the stadion. Although opponents were broadly divided into different groups according to age, there were no specific weight classes. Competitors were expressly forbidden from punching, grabbing the opponent's genitals, biting, tripping, breaking the opponent's fingers or eye gouging. A Hellanodikes observed the fight at close range, ready to use his rhabdos in case one of the competitors infringed the rules. Pale was associated with the mythological character Palaestra, daughter of Hermes. According to Philostratus the Elder (II.32), she was a short-haired, feisty woman capable of beating almost anyone in a wrestling match. ‘Palaestra’ was also the name given to the area of a gymnasion used to train wrestlers.

Animation 6 wrestling

Once all five events had been held, the winner of the pentathlon was announced by a herald. This was a dramatic moment. The victor was awarded a ribbon (tainia) and a palm branch (klados phoinikos) and paraded around the stadion as the crowd cheered and threw flowers and ribbons. The losers quietly retired and the day ended with sacrifices at the shrine of Pelops.

7 Day Three: Sacrifices (Hecatomb) and feast

On the morning of day three, athletes, gymnastai, priests, and Hellanodikai gathered at the Prytaneion for the procession that would begin a day of sacrifice and feasting. Individuals would have been sacrificing animals on their own behalf at a range of altars, but this would be the official sacrifice, an impressive spectacle of great religious significance. Animal sacrifice was the central ritual act of Greek religion, so the sacrifice to Zeus would have been the focal point of the Olympic festival. Instead of a conventional architectural structure, Zeus was honoured by an unusual altar built from the ashes of the thighs of animals sacrificed there. According to Pausanias’s detailed description (5.13.8-14.2), in his day the mound was 42 metres in circumference at its base and seven metres high, with flights of stone steps allowing access to the top. Tradition dictated that only the wood of white poplar should be used for Zeus’s sacrifices.

The worship of Zeus in the Peloponnesian peninsula long predated the Games. Greek gods were thought to watch and enjoy festivals much as humans did, so the procession had to be graceful and it was an honour to participate in it. The Hellanodikai led (two of them in the 5th century BCE, up to ten in the 4th century BCE), dressed in striking purple robes. They were followed by seers and priests, and behind them came 100 bulls, destined for sacrifice, led by watchful attendants. Then came the sacred ambassadors from across the Greek world, followed by the competing athletes with their gymnastai and closest friends. Watched by crowds of spectators, the procession (pompe) travelled along the Altis boundary and round to the Great Altar. Like all Greek altars, Zeus’s Great Altar was situated outside, where people could gather.

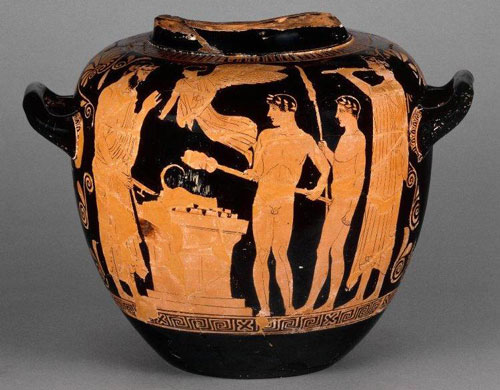

Figure 14 Scene from a 5th century BCE Athenian red figure stamnos, showing an idealised sacrifice carried out by victorious athletes in the presence of the winged goddess Nike. British Museum inv. no. 1839,0214.68.

After ritual hand washing, prayer and the scattering of barley, the first bull would be stunned and its throat cut. Thigh-bones and fat, the god’s portion, would be burnt on top of the altar to please Zeus with their meaty aroma. With a hundred bulls to sacrifice, that aroma must have become quite strong. Sacrifices were usually more modest. This hecatomb – the sacrifice of a hundred bulls, involved a huge financial outlay as an especially generous offering to Zeus. As was standard practice at religious festivals, the killing was followed by a magnificent public feast, the meat being distributed amongst all present, with particularly good cuts going to the priests, other worthies and victorious athletes. In addition to barbecued meat, there would have been black-puddings made from the sacrificed animals’ blood, and local produce such as bread and olives, washed down by copious quantities of wine. Sacrifices were almost the only occasion when people ate meat, so the hearty meal and celebrations that followed sacrifices made religious festivals enjoyable and sociable as well as sacred.

Animation 7 sacrifices and banquet

In the Modern Olympics, the sacrificial and religious aspects of the ancient games have been substituted by an emphasis on national and cultural identity. The opening ceremony in particular sets the tone for the modern Games and presents the host nation with the opportunity to make a big statement. This takes the form of a series of spectacles that strongly reference its cultural identity and heritage. Television ensures that the images of the opening and closing ceremonies, as well as those of the athletic competitions themselves, travel instantly across the globe and help to shape the international reaction to the hosting country’s organisation of the games. The Modern Games have thus developed their own complex series of ceremonies and rituals. These have, however, been divorced from any religious or sacrificial connotations; rather they are designed to emphasise national identity under an umbrella of international cooperation.

7.1 Further resources

Readings

Petropoulou, M. (2008) Animal sacrifice in Ancient Greek religion, Judaism, and Christianity, 100 BC to AD 200. Oxford, Oxford Classical Monographs.

Web links

8 Day Four: Running events and combat sports

The start of the fourth day was the morning after the night before. Spectators would still be recovering from the parties and feasts of the previous day. The gymnikoi agones were about to be resumed, divided into two disciplines – running events and combat sports.

8.1 Running Events

The fourth day of the Olympics also started at dawn with a procession from the Altis area. Athletes and Hellanodikai marched towards the apodyterion (the Ancient Greek version of our modern locker room), where the athletes undressed and rubbed oil from the aryballos onto their skin. The Hellanodikai made their way to the Hellanodikaion (the judges’ stand), a small fenced area by the stadion from which they observed the races and ensured that all the rules were being followed.

After the athletes entered the stadion and saluted the cheering crowd, the races began. Just like in the foot races of the pentathlon, the running events of the fourth day were divided into four types: the dolichos, the stadion, the diaulos, and the hoplitodromos. The styles of running and speed of the athletes varied depending on the type of race and distance. The first event was the dolichos (which was the longest of all and therefore gave the audience a chance to take their time settling down first thing in the morning). This was followed by the stadion which shared its name with the track on which it was held. The stadion race was considered especially significant – the entire Olympiad was named after the winner of this event. The last race was the hoplitodromos, which was added to the Ancient Olympics in 520 BCE and was probably viewed by Ancient Greeks with a combination of humour and admiration, with all its collisions, mishaps and clanking noises.

Animation 8 hopplitodromos

Each end of the stadion track was marked by a balbis, which acted as a starting and finishing line. The balbides (plural of balbis) ensured that the athletes' feet were side by side at the start of each race. This suggests that the traditional starting position in the Ancient Olympic races was upright (unlike the modern four-point starting position), and, judging by some scenes on decorated vases, with the arms stretched forward. The balbides at Olympia were some 30 metres long (i.e. approximately the width of the stadion). This restricted the number of competitors that could run side by side against each other. As a result of this limitation, it is likely that the foot races were held in at least two rounds, followed by a final runoff between the victors of each round.

8.2 Combat sports

After the last races had concluded, a brief intermission ensued to allow officials to dig up the skamma on the stadion surface, where the combat events would be held during the second half of the day. The combat sports of the fourth day were divided into two events: pyx (boxing) and the pankration (a form of all-in wrestling).

Pyx was not too dissimilar from our modern boxing. Competitors were only allowed to punch each other (it was forbidden to bite, kick or trip one's opponent). Despite these restrictions, it was still a fairly violent event (judging by scenes from decorated vases, which often show bruised and bloodied pyx fighters). The aim of a pyx match was to knock out the opponent (or force him to admit defeat, which was signalled by raising the index finger, as in pale ). Like modern boxing, pyx fighters did not compete bare-handed – they wrapped their wrists and knuckles (but not their fingers) with long straps called himantes. The himantes were made of tanned oxhide and measured approximately four metres. Their aim was to protect the fighter's hand (rather than the opponent's face). Unlike modern boxing, there were no rounds and a boxer could carry on hitting an opponent even after the latter had fallen to the ground.

Animation 9 boxing

Box 3 Highlight: the morality of violence in sport

Two men square up to each other in front of an excited crowd. The two fighters throw punches at each other and the crowd roars. Perhaps this is a confrontation on a city street on a Saturday night, and the police are arriving to make some arrests. Or perhaps this is a boxing match at the Olympics and the contestants are sporting heroes.

But is there a moral distinction between a street fight and a boxing match? Boxing raises a host of questions about the justification of violence and our attitudes to it. Ancient Greece had an ambivalent attitude towards violence. For instance, blood and death were not shown on stage in plays (with some exceptions), possibly because they were considered distasteful; but Ancient Greek mythology is rife with explicit examples of cruelty, revenge, war, rape and murder. Most people would agree that violence is sometimes justified – in self defence, for example. But is the quest for sporting glory a good reason for trying to land a punch on someone? And is it right that people should take pleasure in seeing two men try to hurt each other?

Perhaps the most familiar objection to boxing is the long-term harm caused to the boxers themselves. The British Medical Association has called for boxing to be banned, citing the damage done to boxers’ brains. This raises broader questions about the role of law and its relation to morality. The BMA’s position can be seen as an example of paternalism – the view that one function of the law is to protect people from themselves. Opponents of a ban point out that boxers choose to fight, knowing the risks. Paternalism, they argue, is an unwarranted attack on freedom.

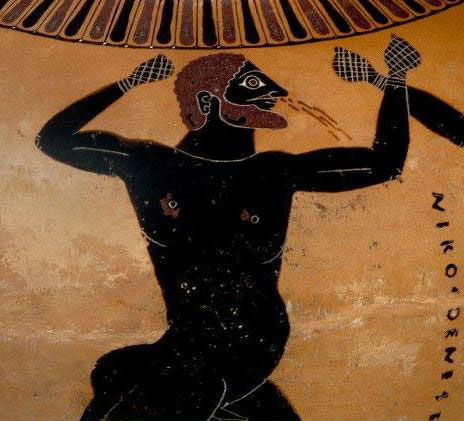

Figure 15 A pyx fighter bleeding heavily at the nose. The scene decorates a black figure amphora from the 6th century BCE. British Museum, inv. no. 1867,0508.968

Pankration (which translates literally as 'all force') was perhaps the most brutal of all Ancient Olympic events. It was a combination of boxing and wrestling, without the use of the himantes. Like pyx, the aim was to knock out the opponent or force him to admit defeat). However, unlike pyx, most forms of physical aggression were allowed: kicking, punching, slapping, holding, tripping, and so on. The only restrictions were the rules against biting and gouging the opponent's eyes. Pankration was closely associated with the myth of Hercules, who, according to tradition, fought a lion with his bare hands (presumably resorting to some of the moves that came to be expected from a pankration match).

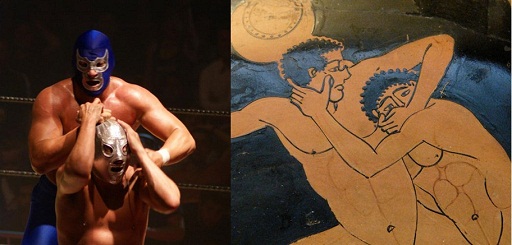

So what’s the difference?: modern Pro Wrestling and Ancient Greek pankration

Figure 16 Left: modern Pro-Wrestlers wearing Mexican Lucha-style masks. Right: two pankratiasts in an armlock decorating a red figure kylix from the 5th century BCE (British Museum, inv. no. 1850,0302.2).

What do you think are the main differences between modern Pro Wrestling and the Ancient Olympic pankration? Once you have come up with a few ideas, click on ‘reveal comment’ to read some of our suggestions.

Comment

Modern Pro Wrestling attracts large crowds. The atmosphere is riotous, with a mix of loud applause, cheering and booing. The public, who is titillated by the acrobatics and the more extreme forms of violence on the ring, incites the fighters with their shouts and gesticulations. Many of the wrestlers are already well known to the spectators – a few (like Hulk Hogan, Andre the Giant or Hacksaw Jim Duggan) have even achieved what some would consider star status.

So far, this does not seem too dissimilar from what we would expect to see in an Ancient Greek pankration match two and a half millennia ago. The Ancient Greek public standing around the stadion at Olympia cheered and reacted passionately to the sheer physicality of the event. Some pankratiasts had a cult following (like Theagenes of Thasos or Diagoras of Rhodes). In addition, the pankration, like a modern Pro Wrestling match, was not divided into rounds, had a referee (the Hellanodikes) observing the fight at close range and was fought until one of the opponents admitted defeat.

However, this is where the similarities end. Modern Pro Wrestling is not an Olympic event – it is a spectacle of the entertainment business, based mostly on theatre and choreography. Pankration, on the other hand, was firstly and foremost an athletic sport event. The wrestlers were not acting or performing rehearsed moves that had been agreed beforehand – they were competing for glory. Ancient Greek pankratiasts used no props (like the type of masks, extravagant sun shades, boots, chains, or even axes that we might expect from a WWF or Mexican Lucha Libre show); in fact they were completely naked! Unlike Modern Pro Wrestling matches, which are generally fought on an elevated wrestling ring with ropes, ring posts and a padded canvas mat surface, Ancient Greek pankration matches were fought in a simple skamma on the stadion.

All in all, pankratiasts were expected to act less like extravagant film stars and more like serious, focused athletes aspiring to achieve arete and kleos through their victory. Having said that, we do hear of cases where pankratiasts indulged in ostentation and antics. According to Polybius, the pankratiast Kleitomachos of Thebes once interrupted a fight mid-match to have a little chat with the public in order to criticise his opponent and try to gain the sympathy of the spectators!

8.2.1 Further resources

Readings

Boddy, K. (2008) Boxing: A cultural history. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Van Wees (2000, ed.) War and Violence in Ancient Greece. London and Swansea, Duckworth and the Classical Press of Wales.

Web links

9 Day Five: Honouring the victors

The last day of the Ancient Olympics was dedicated to honouring the victors. You may remember from the introduction an image of goddess Nike holding a wild olive branch, decorating one of the medals that was awarded in the 1896 Olympics. Before the start of the Ancient Olympic festival, a boy whose parents were still alive cut various branches from a sacred olive tree (the kotinos kallistephanos), which grew in the Altis area of Olympia and, according to Pindar (Olympian 3.60) , had supposedly been planted there by Hercules himself. These branches, which had to be cut with a gold sickle, were used to make the olive wreaths that were later awarded to Olympic victors.

On the fifth day of the Olympics, the victorious athletes and ten Hellanodikai marched in procession towards the Temple of Zeus in the Altis. The olive wreaths were brought from the Temple of Hera, where they would previously have been on display on a gold and ivory altar. The victors, wearing ribbons around their arms and heads and carrying palm branches, passed before the Hellanodikai who ceremonially crowned them with the wreaths.

Animation 10 procession

As well as the ribbons, palm branches and the olive wreath, victorious athletes were awarded free dinners for the rest of their lives. Tempting as this might sound, compared to the financial rewards often granted by governments to modern Olympic victors, these prizes might seem something of a let down after such efforts and sacrifices. In fact, they were intentionally chosen to be ephemeral and with little or no material value in order to emphasise the fact that the real reward was the glory that came with the victory itself – the admiration of fellow citizens, the honour of having one's name entered into the register of Olympic victors and the satisfaction of Zeus (in whose honour the festival had been held).

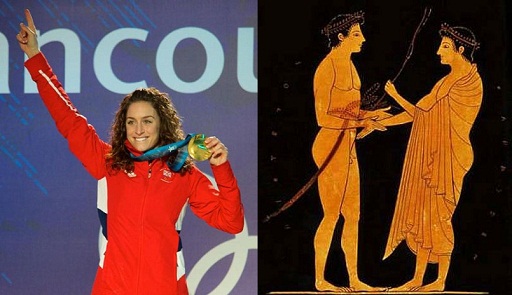

So what’s the difference?: modern and Ancient Greek celebrations of victory in sport

Figure 17 Left: modern Olympic athlete Amy Williams displays her gold medal in the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. Right: victorious athlete (left) with a stephanos, klados phoinikos and tainia, receiving his award from a Hellanodikes (right) on a red figure vase (6th century BCE).

What do you think are the main differences between modern and Ancient Greek ideas of victory in sport? How are these differences manifested in the honouring of the victors? Once you have come up with a few ideas, click on ‘reveal comment’ to read some of our suggestions.

Comment

The differences between ancient and modern Olympic victory have a lot to do with the contrast between the economics of religious sacrifice and those of the commercial market. In both contexts, however, there is a high value placed on human virtue as it is expressed in athletic performance. The enduring connection between striving, victory and virtue is at the heart of Olympic philosophy, ancient and modern.

The ancient Olympic victor was decorated with ribbons, a palm branch and a wreath of wild olive - symbols that dedicated him to the gods. Victory was less about receiving prizes than becoming a prize, a kind of offering to the gods. The modern Olympic victor, on the other hand, receives an enduring gold medal. The prize itself is not worth much money but the expectation is that it will attract lucrative commercial endorsements, professional sports contracts, even paid speaking engagements.

In recompense for the sacrifice of an Ancient Olympic victor, the gods were expected to benefit the community in concrete ways such as healing from disease or successful harvests. The victor therefore becomes a prized member of the community and is offered meals at public expense. At least one city’s confidence in the divine favour that a victory brought was so great that it even dismantled its protective walls for the athlete’s homecoming. The worth of the modern Olympic victory is based on marketing rather than religious beliefs, but at the same time it derives from similar ideas about the link between victory and virtue. We buy products that athletes endorse, watch them play sports, and listen to their speeches because we admire their virtues and hope to emulate them in our own lives. Olympic athletes inspire us even in our modern struggles.

The glory of ancient Olympic victory was characterised by its ephemerality. In contrast to the immortal gods, human excellence requires struggle and lasts only for a moment. But by resembling a god, if only for a moment, the athletic victor offers an inspiring example of our human potential. The transience of victory seems less emphasised today, but the reality is that Olympic glory rarely extends beyond the proverbial 15 minutes of fame. Modern Olympic medallists cash in quickly on their image, because it is soon forgotten. The general dream of Olympic victory, however, continues to inspire young and old alike.

Of course, many athletes used their Olympic victory as a platform on which to build highly profitable careers as high status, influential individuals. Their return home (eiselasis) was a momentous occasion. They were met by their families and fellow citizens and given a hero's welcome. A banquet and a symposion were normally organised by the athlete’s family in his honour. In addition, the wealthier families sometimes commissioned a life-size statue to commemorate the achievements of the athlete. The original statues are almost completely lost, but we can get a good idea of their visual impact from the copies set up in Roman gardens and baths and the description of Olympia by Pausanias. The different postures and equipment of the statues designate different contest disciplines, such as the hoplitodromos, pale and tethrippon racing. The powerful bodies in real-looking action poses were meant to convey the innate superiority of the aristocrats participating in the games. The practice of dedicating athletic statues began in the 6th century BCE and in many Greek sanctuaries soon produced dense accumulations of statues, as described by Pausanias in his writings.

Figure 18 The charioteer of Delphi, an Ancient Greek bronze statue from the 5th century BCE made to commemorate the victory of a tethrippon team in the Pythian Games.

If the athlete’s family were feeling particularly lavish and wanted to make sure that the news of the Olympic victory travelled far and wide, they had the option to commission a victory ode from a poet. These victory odes, which were created principally to extol the virtues of the athlete and his city, became an important element of the literary tradition of Ancient Greece. As Armand D’Angour explains (below), the victory odes of Pindar, in particular, were admired and regarded as masterpieces of literature.

Video: Armand D’Angour

Dr Armand D'Angour, author of the Pindaric Ode for Athens 2004 and the Homeric Ode for London 2012, tells us about Pindar and the tradition of ode composition as part of the honouring of victors in the Ancient Olympics.

Transcript: Ode for Athens 2004: English translation (audio)

9.1 Further resources

Readings

Kyle, D.G. (1996, July/August). Winning At Olympia. Archaeology, 49, 26-37.

Pindar (1997) Olympian Odes, Pythian Odes. Ed. and trans. William H. Race. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, Harvard University Press.

Web links

10 Conclusion

The modern Olympics owe a lot to the Ancient Greek Games. Many of the sporting events that we have grown accustomed to watching on TV or cheering on in our Olympic stadia (e.g. boxing, javelin, discus, long jump, foot races) are directly inspired by the competitions that were being held in Olympia more than two thousand years ago.

Perhaps more importantly, many of the underlying ideals of the Ancient Games are still at the heart of our modern Olympics. For example, the Olympic values are respect, excellence and friendship, while the Paralympic values are determination, equality, inspiration and courage. These are principles that we aspire to as a modern society, but their origins lie further back in time – they are the legacy of the Ancient Greek world.

Today, as in Ancient Olympia, cases of cheating, armed conflicts and allegations of corruption do occasionally mar the sporting events, but the modern Games still strive for the athletic ideals that are encapsulated within the Olympic spirit. These athletic ideals are constructed around Classical notions such as kalokagathia, arete, isonomia and kleos. We may have stopped hitting our athletes with a rhabdos when they misbehave, but by continuing to embrace the Olympic values of the Classical world, we strengthen the connections between the modern Games and their ancient origins in the Peloponnesian peninsula.

10.1 Further resources

Readings

Cousineau, P. (2003) The Olympic Odyssey: Rekindling the True Spirit of the Great Games. Quest Books, Wheaton Illinois.

Reid, H. and Evangeliou, C. (2008) "Ancient Hellenic Ideals and the Modern Olympic Games" in Barney, R. et al. (eds.) Pathways; Critiques and Discourse in Olympic Research. Ninth International Symposium for Olympic Research. Beijing: Capital University of Physical Education.

Web links

Introducing the Classical world

Olympic Movement virtual museum

British Olympic Association (BOA)

NHS Olympics: What’s your Sport?

International Olympic Association. The Legacy of Ancient Greece

11. Quiz

Question 1

a.

A. Started the first truce of the Ancient Olympics

b.

B. Banned the Olympics

c.

C. Won four pentathlons in a row

d.

D. Occupied Olympia’s sacred grove while the Games were in full swing

The correct answer is b.

Answer

Theodosius I was a Roman emperor who adopted Christianity as the official religion of the empire. Between 389 and 391 CE, he banned all forms of non-Christian religion, including the Panhellenic Games of Greece, which, at that time, was part of the Roman empire.

Question 2

a.

A. throwing an opponent on his hip

b.

B. throwing an opponent on his back

c.

C. forcing an opponent to admit defeat by raising his arm with the index finger pointing up

d.

D. All of the above

The correct answer is d.

Answer

A pale match could be won either by throwing an opponent on his hip, shoulder or back, or forcing him to admit defeat.

Question 3

a.

A. Agony

b.

B. Strength

c.

C. Naked

d.

D. Male

The correct answer is c.

Answer

The gymnasion derives its name from the Greek word for ‘naked’, because athletes trained and competed with their clothes off.

Question 4

a.

A. stadion

b.

B. dolichos

c.

C. hoplitodromos

d.

D. None of the above

The correct answer is d.

Answer

The Ancient Olympics did not have a marathon race. Marathon racing was introduced as an Olympic event in 1896 by Michel Bréal and Pierre de Coubertin.

Question 5

Link the sporting equipment with their appropriate sporting events in the right column by dragging and dropping the phrases.

himantes

boxing

hisplex

foot race

tethrippon

chariot race

halteres

long jump

ankyle

javelin throw

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

himantes

hisplex

tethrippon

halteres

ankyle

a.foot race

b.long jump

c.boxing

d.chariot race

e.javelin throw

- 1 = c

- 2 = a

- 3 = d

- 4 = b

- 5 = e

Answer

Himantes were long oxhide straps that were wrapped around the boxer’s wrists and hands.

The hysplex was a starting mechanism that resembled a long wooden fence. Its aim was to reduce the number of false starts in foot races.

The tethrippon was a small, light chariot drawn by four horses. It was fast and very dangerous to drive.

Halteres were weights made of stone or metal, used in the long jump. They were also used during an athlete’s training as an ancient equivalent of dumbbells.

The ankyle was a strap wrapped around the javelin and held between two of the athlete’s fingers in a loop. It was used to increase the javelin’s speed and accuracy.

Question 6

a.

A. The governor of Elis

b.

B. Spartan war heroes

c.

C. Pallas Athena, the patron of Athens

d.

D. Zeus

The correct answer is d.

Answer