Attachment in the early years

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 5:21 PM

Attachment in the early years

Introduction

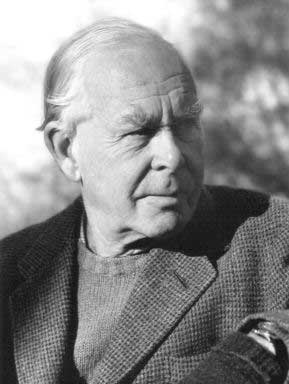

For most, if not all, people, the attachments we have with others are at the centre of our lives and play a large part in determining how happy and contented we are. Attachments are two-way, dynamic processes between people and start from the beginning of life. John Bowlby, often called ‘the father of attachment theory’, was the key figure in developing a complex model of the attachment system and proposing how it serves to provide security to individuals while also encouraging them to be active in the world. Research based on this theory is revealing the significance of the early years of life in the formation of attachments that go on to be central throughout life. This free course gives an introduction to this exciting area of contemporary study.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course E219 Psychology of childhood and youth.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

describe attachment classifications and how they are assessed

describe the features of caregiving that influence attachment, and the significance of attachment for lifespan development

discuss why the attachment system is an adapted and adaptive mechanism

recognise the need for ethical conduct in research carried out with children

1 Introduction to attachment

The following audio is an interview between Professor Elizabeth Meins, from the University of York psychology department and John Oates of The Open University. Professor Meins’s research focuses on caregiver ‘mind-mindedness’ and its role in predicting children’s development and social cognition.

The audio will help to give you an overview of the topic of attachment in young children and will highlight some of the key themes. It is important to listen to this before continuing with this course.

Transcript: Attachment in the early years: Elizabeth Meins

[MUSIC]

[MUSIC]

Human beings are social animals; the ‘ties that bind us’ together are at the centre of our shared lives. From the moment of birth, attachment relationships are crucial to our survival and well-being. Research into attachment – what it is, how it develops and its role in our adult relationships – is one of the most active areas of research in psychology.

1.1 The needs of immature young

Human infants, and indeed the newborns of any mammal species, cannot survive alone. They need the feeding, attention, care and protection of more mature individuals to enable them to grow and develop. By definition, newborn mammals need access to nutrition via suckling. As well as the need for food, there is also a need for security in terms of the protection that a more autonomous member of the same species can give – for example, against predators which find defenceless young animals an attractive and easy prey – and the need to learn crucial life skills from more knowledgeable and experienced individuals.

Two photographs. One shows a bird hovering above two chicks in a nest, whose beaks are open to receive food from the parent bird. The other photograph shows a female deer standing with her young fawn reaching up under to suckle.

For a species to survive, there have to be efficient and robust mechanisms of behaviour in both the young and the carers that keep them together during the period of dependent immaturity.

It is not surprising that evolution has favoured such mechanisms and that they have, to varying degrees in different species, become instinctive in that they do not have to be learned. A particularly striking example is where the hatchlings of some bird species, such as ducks and geese, ‘imprint’ on their mother and follow them around. This provides them with protection and opportunities to learn about how to garner their own food resources.

A photograph of a duck swimming along with twelve ducklings swimming behind her in a line.

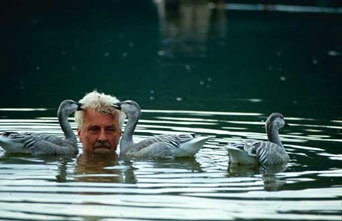

Konrad Lorenz, an ethologist (one who studies animal behaviour), succeeded in having young greylag goslings imprint on him and follow him, by being the first moving object that the chicks encountered after hatching. He found that these young birds imprint on any moving object that is in the immediate environment during a ‘critical period’ shortly after hatching happens.

This photograph shows a man, Konrad Lorenz, with just his head above water. Three goslings are swimming around him; two of them are pecking at his hair.

However, it is important to note that although the behaviour (following) is fixed, the target of the behaviour is not, in that it can be a goose parent, a human or a toy train, or indeed any other object. So the behaviour is adaptable at the same time; it involves some rapid learning about which object in the environment is to be the focus.

1.2 Attachment and human evolution

The ‘environment of evolutionary adaptiveness’ (EEA) in which earlier pre-human species evolved into Homo sapiens was very different to the world in which most of us live nowadays. For most humans, we live a largely ‘built’ environment; even what most of us think of as ‘wild’ countryside is to a greater or lesser extent the ‘tamed’ result of human activity. Apart from a few pockets of lived-in ‘natural’ places in remote corners of the globe, humans no longer need to be alert to the presence of predators, and we are largely protected against extreme environmental conditions because of our housing and clothing, and the ‘constructed’ nature of our current life-spaces.

One of the striking, distinguishing features of human development as opposed to the development of other animals is the long period of dependency of infants and then children on their caregivers. The psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott wrote that:

there is no such thing as a baby … if you set out to describe a baby, you will find you are describing a baby and someone. A baby cannot exist alone, but is essentially part of a relationship ... .

Here he is stressing that existence itself starts in the context of a providing relationship.

2 Attachment theory

Although it has long been recognised that humans form strong attachment relationships – not only between infant and mother, but also later in the lifespan via close friendships, sibling bonds, and romantic and marital relationships – the underlying processes have only been the subject of psychological enquiry since the middle of the twentieth century. Prior to this, it was widely thought that the main reason for attachments developing between mothers and their infants is that the mother satisfies ‘primary drives’ in the infant; especially the needs for sustenance, which the infant is not able to supply for herself.

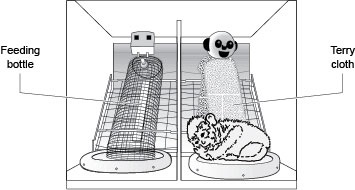

However, is it simply the assurance of basic physical survival that human infants need, or is the relationship itself also important? A classic set of studies with young monkeys by Harry Harlow (1958) explored this question.

This artwork shows a box with two simple models of monkeys, one with a wire-mesh body and one with a terry-cloth body. The wire body has a feeding bottle attached. A young monkey is curled up against the base of the terry-cloth model.

Harlow separated macaque infants from their mothers at birth and raised them in isolation cages. He found that close, frequent attention from human carers led to higher survival rates than care by captive natural mothers and that the infant monkeys learned to come to their human carers for food and comfort. He also noticed that the macaque infants often clung to the cloth pads that were used to cover the bases of the cages and they protested when these pads were removed for cleaning. He found that even a simple wire-mesh cone was often used as a refuge to cling to when the infants were frightened, and that this helped to boost survival rates. Covering the cone with cloth helped even more. Harlow then raised infant monkeys in isolation with only two simple ‘mother surrogate’ models available to them. In a key experiment, one of these ‘mothers’ was made from wire mesh and had an attached milk bottle from which the monkey could feed. The other ‘mother’ had a soft towelling surface but did not deliver any food.

The initial results were striking: the infant monkeys overwhelmingly preferred to cling to the ‘cloth mother’ rather than the ‘wire mother’ and when they were frightened, they almost always went straight to the cloth mother and held tightly to it – in spite of the fact that only the wire mother was their source of food. As the infants got older, these preferences increased rather than decreased. Furthermore, when these infant monkeys were put into an unfamiliar environment (a new room), the presence of their cloth mother greatly reduced their panic reactions. If the cloth mother was available, the infants would use it as what Harlow called a ‘base for operations’ (1958, p. 679), exploring the new room and its objects while periodically returning to cling to the mother surrogate. These findings were taken as strong evidence that there is another factor, stronger even than the provision of the basic necessity of food, which determines how macaque infants become attached to one object rather than another. Crucially, when Harlow moved the milk source to the cloth mother, this seemed to have no effect on the amount of clinging. Harlow had found that a bond with an object could provide security in the face of threat. What he called ‘contact comfort’ had emerged as being at least as significant as the basic needs for nourishment.

A photograph of a child aged about 4 years holding a white cloth against his cheek.

The research with different animals brought to the fore a series of questions that have been of great value in researching human development. The most important of these are as follows:

- Can infants bond with anyone or does it have to be the mother?

- What features of parenting are important for attachment?

- Does early parenting affect later life?

A central figure in research and theory addressing these questions is John Bowlby, whose work over four decades from 1940 established a strong, elaborated and productive theory, around the central concept of ‘attachment’. His interest in theorising attachment came about because of his involvement through case work and research with children who had mental health problems or were involved in criminality; so-called ‘juvenile delinquents’, to use a term in common use at the time. He recognised a common theme in the life histories of these children; that they had either lost one or both parents early in childhood through separation or death, or they had had very poor parenting. The term ‘maternal deprivation’ originated with Bowlby, based on this insight.

2.1 Internal working models

A central premise of attachment theory is that infants learn about ways of relating from early relationships with their attachment objects and build up a set of expectations about themselves in relation to others. On the basis of these first experiences they build what Bowlby termed an ‘internal working model’ (IWM), which means they can approach new situations with some prior ideas about how they can cope in the face of threat. This IWM has three elements: a model of the self, a model of ‘the other’ and a model of the relationships between these (Bowlby, 1969, 1973, 1988; Bretherton, 1990, 1991, 1993).

For example, one infant might have a father as the primary carer who is quite devoted and, as well as being with the infant most of the time that she is awake, is also very responsive to the infant’s distress. This infant will, thus, be likely to construct an IWM in which self is seen as capable of calling for comfort when needed and as worthy of receiving comfort. The model of other will represent an expectation that comfort will be given when needed and that the other will show concern for the infant’s state. The relationship part of this IWM will include an expectation of satisfactory resolution of crises, with mutual communication.

By contrast, another infant may have a carer who is quite depressed, spending a lot of time in a self-absorbed state and with a generally low mood. This infant may spend long periods of time alone or with an emotionally unavailable carer, where distress goes unacknowledged. When infant distress is responded to, it may sometimes be that the carer feels the distress as being invasive and the infant is handled roughly as a result. On other occasions, the infant’s distress may trigger a need in the carer for them to be cared for, and the carer will seek to reverse roles. In this situation, the infant’s IWM will have an ambivalent model of self: as sometimes worthy of attention but not always, as sometimes receiving comfort, but at times also expected to give comfort when distressed. The model of other will be similarly confused between availability, ignoring and rejecting aspects. The relationship model will also have multiple expectations. So an infant in this latter situation will have an IWM that is less able to generate accurate predictions of what will happen in the case of distress.

A second central premise of attachment theory is that IWMs arise out of the oft-repeated experiences of the specific nature of the early relationships between infants and carers and, crucially, that the IWMs persist onwards into childhood and beyond. The argument goes that these expectations about self, other and relationships are carried into subsequent interactions with other people, providing a template to make initial sense of new encounters:

No variables ... have more far-reaching effects on personality development than have a child’s experiences within his family: for, starting during his first months ... in his relations with both parents, he builds up working models of how attachment figures are likely to behave towards him in any of a variety of situations; and on those models are based all his expectations, and therefore all his plans, for the rest of his life.

Thus, in typically bold fashion, Bowlby set out this central tenet of attachment theory, and this now serves as a springboard to the topics that are considered in the rest of this course.

2.2 What Bowlby did and didn’t say

Theoretical ideas about early attachment tend to touch us more deeply than some other psychological theories, since we are often drawn by them to reflect on our own early experiences and how they have affected us, for good or ill. Add to this the forthright nature of Bowlby’s thinking and writing, and the controversial nature of his theory becomes easier to understand. Bowlby’s attachment theory has often been misrepresented and has been, in consequence, criticised for things that he didn’t actually state, so it is worth briefly reviewing these to highlight some important aspects of what he did say.

Mother as single attachment figure?

It is a common misapprehension that Bowlby believed that a child basically needs a single attachment, ideally to the biological mother. Although Bowlby believed that healthy attachment in infants is based on relatively long-term, stable relationships with carers, he did not see a single attachment as necessarily being the best and only way of achieving this. Indeed, he explicitly recognised that the attachment to a ‘father’ can complement and support an infant’s attachment to their ‘mother’ and that other people in an infant’s social world can also play important roles. He also came to the conclusion that there is nothing sacrosanct about this ongoing care being provided by the biological parents and that it can equally well be provided by other consistently and reliably available people. Indeed, he argued that a variety of attachment objects could lead to a more fully developed and differentiated IWM, since it would encompass relations with different people, better preparing the child for forming relationships with a wider range of people later on in life.

Understanding this aspect of attachment theory has a number of important practical implications. For example, it suggests that fathers or other male caregivers can provide a perfectly adequate attachment figure, as can female caregivers, other than the biological mother. Hence, a belief that only the mother can be an effective caregiver is not supported by attachment theory, which is relevant for views about mothers working while their children are very young, or for social workers concerned about placing children who are at risk.

Infants form attachments with those people around them who care for them sensitively and consistently. The more frequently, sensitively and consistently a person cares for an infant, the higher that person becomes in the infant’s ‘hierarchy of attachment figures’, and the more likely it is that this is the person who will be turned to by the infant in times of stress. Looking at this globally, most infants are embedded in a network of ‘carers’, including not only siblings, grandparents and other relatives, but also other members of the community.

Rigidity of IWMs

Although a key feature of Bowlby’s view of IWMs was that they are the basis for the relationships that infants come to form later in their lives, he did not see them as permanently and unalterably fixed during infancy. As previously stated, contact with a greater variety of people with whom an infant can form attachments is a benefit, according to Bowlby, who saw this as a way in which IWMs can be modified and develop. This part of the theory also began to further question the idea that infants need just a strong bond with a totally available and responsive biological mother for healthy emotional development. This flexibility in the attachment system is another aspect of its adaptive significance in evolution, allowing the infant and then the child to adjust to changes in the caregiving environment.

2.3 ‘Good-enough’ mothering

Bowlby was much influenced by the work of Donald Winnicott, who, in his work with mothers and infants, came to see how important it is for a mother to be emotionally available to her infant, and for a ‘system’ of two-way communication to be built up. At the same time, he did a great deal to challenge the idea of a ‘perfect mother’. He strongly believed that an important part of a mother’s role is to allow her infant to experience tolerable frustrations. He coined the term ‘good-enough mother’ to describe a mother who allows just the right amount of delay in meeting an infant’s needs to encourage both tolerance of waiting and confidence in ultimate satisfaction (Winnicott, 1964). This then leads, according to Winnicott, to a healthy development of independence and sense of self (Winnicott, 1965). He did not believe that a mother was doing the best for her child if her aim was to alleviate all distress, discomfort and frustration at the earliest possible opportunity.

3 Attachment classification

Ainsworth, who spent some years in the early 1950s working with Bowlby, initially examined the effects of ‘maternal deprivation’ (the lack of an adequate mother experience in infancy) on children’s development (Ainsworth, 1962).

In 1954, she left for Africa, and moved attachment theory forward through her observations of 28 mothers and their children in Uganda. She noted that, although there were some important differences between children in how they behaved when they were separated from their mothers, it was actually during reunions after separations that differences between children’s behaviours were most evident. She identified three different types of attachment: secure, insecure and absent. She later spent a long period in Baltimore, USA, closely observing and recording the behaviour of two further samples of infants and their mothers. It was during this time that she clarified her attachment categories by subdividing the insecure classification into two. She also developed a standard method for assessing attachment in infants aged around 1 year, the ‘Strange Situation Test’ (SST), which has become a ‘gold standard’ laboratory technique for attachment researchers (Ainsworth et al., 1978).

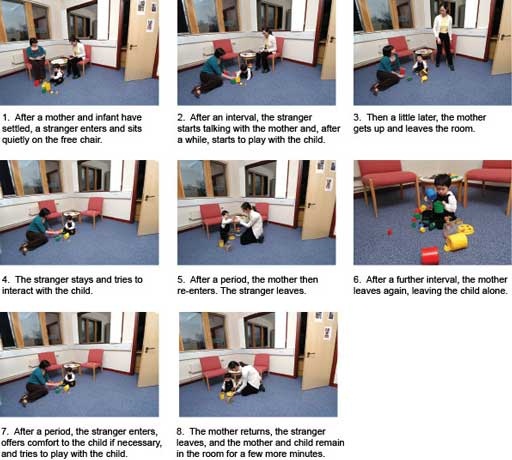

The procedure has eight episodes, designed to expose infants to increasing amounts of stress in order to observe how they organise their attachment behaviours with their parents when distressed by: being in an unfamiliar environment, the entrance of an unfamiliar adult, and brief separations from the parent.

Box 1: The Strange Situation Test

This assessment is carried out in an observation laboratory, with video cameras to record the behaviour of mothers and their infants. The room contains two easy chairs, a play area, perhaps defined by a rug, and a set of toys.

After a mother and infant have settled, a series of eight episodes follows. The video recording of the whole session is then coded by trained observers. (This method of assessing and classifying attachment is discussed further in Section 6.)

Eight photographs of a room with two easy chairs, a low table and some toys on the floor. A child is in each photograph, sometimes with a mother figure, sometimes with a stranger and sometimes either alone or with both people. The captions describe what is happening in each photograph:

- After a mother and infant have settled, a stranger enters and sits quietly on the free chair.

- After an interval, the stranger starts talking with the mother and, after a while, starts to play with the child.

- Then a little later, the mother gets up and leaves the room.

- The stranger stays and tries to interact with the child.

- After a period, the mother then re-enters. The stranger leaves.

- After a further interval, the mother leaves again, leaving the child alone.

- After a period, the stranger enters, offers comfort to the child if necessary, and tries to play with the child.

- The mother returns, the stranger leaves, and the mother and child remain in the room for a few minutes.

According to attachment theory, infants who have formed a good attachment to one or both parents should be able to use these figures as secure bases from which to explore the novel environment, because their IWMs contain representations of available parent figures. The stranger’s entrance should lead infants to inhibit exploration and draw a little closer to their parents, at least temporarily. The parent’s departure should lead infants to attempt to bring them back by crying or searching, and to less exploration of the room and toys. Following the parent’s return, infants should seek to re-engage in interaction and, if distressed, perhaps ask to be cuddled and comforted. The same responses should occur, with somewhat greater intensity, following the second separation and reunion. In fact, this is how about 65 per cent of infants, studied in a number of different countries, behave in the Strange Situation (van IJzendoorn and Kroonenberg, 1988), although there is substantial variation in this figure both within and between countries. Following the definitions developed by Ainsworth and her colleagues, these infants’ relationships are classified as securely attached (Type B) because their behaviour conforms to theoretical predictions about how babies should behave in relation to their primary caregiver if they have established a good attachment.

By contrast, some infants seem unable or unwilling to use their parents as secure bases from which to explore, and they are called insecure. Some insecure infants are distressed by their parents’ absence, and behave ambivalently on reunion, seeking contact and interaction but angrily rejecting it when it is offered. These infants are conventionally labelled insecure-resistant or ambivalent (Type C). They typically account for approximately 15 per cent of infants (van IJzendoorn and Kroonenberg, 1988). Other insecure infants seem little concerned by their parents’ absence. Instead of greeting their parents on reunion, they actively avoid interaction and ignore their parents’ bids. These infants are said to show insecure-avoidant attachments (Type A) and they typically constitute about 20 per cent of infants (van IJzendoorn and Kroonenberg, 1988). Further research has also described a fourth group of infants (Type D), whose behaviour is ‘disoriented’ and/or ‘disorganised’ (Main and Solomon, 1990). These infants simultaneously show contradictory behaviour patterns, and incomplete or undirected movements, and they seem to be confused or apprehensive about approaching their parents. Many of these infants appear to have been maltreated by their parents.

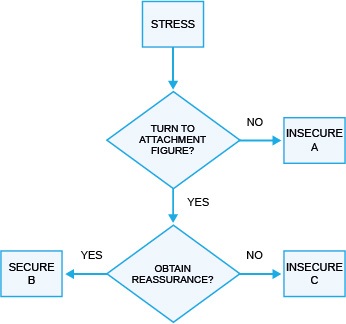

These varied reactions (for the three main categories) can be summarised in a simple flow chart:

Reading from the top of this diagram, first there is a rectangular box with the text ‘Stress’ inside. An arrow leads down from this box to a diamond-shaped box with the text ‘Turn to attachment figure?’ inside. An arrow labelled ‘No’ goes to the right from this box to a rectangular box with the text ‘Insecure A’ inside. An arrow labelled ‘Yes’ points downwards to another diamond-shaped box with the text ‘Obtain reassurance?’ An arrow labelled ‘No’ goes to the right from this box to a rectangular box with the text ‘Insecure C’ inside. An arrow labelled ‘Yes’ goes to the left from the diamond-shaped box to a rectangular box with the text ‘Secure B’ inside.

The generally accepted coding system for the SST further classifies a child’s attachment into a sub-category of the three main categories (A1, A2, B1, B2, B3, B4, C1 and C2).

Research summary 1: How good is the SST as a measure of attachment?

One measure of the value of the SST is that it has been used in a large number of studies that have identified associations between SST attachment classifications and preceding, contemporaneous, and subsequent developmental measures. It is limited, however, in that it can only be used with children aged between about 9 and 18 months. A standard way of assessing the reliability of a measure is to repeat it within a short time period. Unfortunately, this is not possible with the SST as the assessment sensitises children and they react differently if the procedure is repeated. There have been criticisms of the categorical nature of the coding, and attempts have been made to instead use a series of rating scales, but these have not been very successful and are not commonly used. Observations of children in the home situation, and parental report using structured methods, have also been used and these have, in the main, been found to correlate with SST classifications. However, the crucial feature of the SST is that it ‘activates the attachment system’, which is not the case for children in their home environment, where they are likely to feel more secure.

3.1 Attachment and internal working models

According to attachment theory, the analysis of the SST indicates the three main forms that a child’s internal working model can take.

A child with a Type A attachment has a rather troubled attachment to her parent. She is often not upset at separation, and tends not to get close to her parent even when they are reunited after a separation. Often, she turns away from, rather than towards, the parent. She seems to expect the parent’s response to be inappropriate and the relationship to be difficult, and she seems to lack a solid sense of herself as worthy of affection.

A child with a Type B (secure) attachment has an image of her parent as a secure base, who is available for comfort. She also has an image of herself as worthy of her parent’s attention and love, and can gain some comfort from this when separated, having confidence that her parent will return. Her reactions to separation do not show panic; she has some capacity to contain them in the knowledge of her parent’s availability. She is able to use her parent for comfort, and shows pleasure at reunion. She has an untroubled expectation of closeness and warmth between people, and this is also shown in her being able to accept some contact with the stranger.

A child with a Type C attachment is likely to show distress at the separation, suggesting that the parent’s presence is important to her. But she seems to lack a firm belief that her parent will return, or that the parent will be able to comfort her effectively on return, and she thus fails to use her parent as a source of comfort at reunion. She is not easily able to comfort herself, nor does she seem to feel herself worthy of affection from her parent. She rejects the stranger’s attempts to console her. Her expectation seems to be a pessimistic one, that upset cannot be eased by another.

Disorganised behaviours (Type D) show a child being unable to ‘know what to do’; there seems to be a lack of clear expectations of what others can do or consistent strategies for handling stress. The child may seem to be somewhat hesitant about contact, not quite sure whether it is something to be sought or not, and there is little obvious goal seeking in the behaviour. The child may tend to turn to herself for comfort. She seems somewhat ‘dazed’ or confused, and may show repetitive, stereotyped movements.

Each type of attachment is associated with a different internal working model of self, other and the relationship. For example, the child whose behaviour is predominantly disorganised seems to lack a coherent IWM to structure their behaviour.

Following Bowlby’s theory that a child’s IWM will affect how they approach a new relationship, someone with a secure attachment, for example, might approach a relationship with a degree of confidence that the other will respond positively, while someone with an insecure-ambivalent attachment may be more likely to be hesitant and rather wary. Avoidant attachment is likely to be associated with a lack of motivation to relate to others. Insecure children with disorganised attachment-related behaviours are likely to find it hard to approach new relationships in consistent ways; for example they may ‘launch’ an attempt at relating but then fail to follow it through.

4 Influences on attachment

Because there is a great deal of variability in associations between parental behaviour and attachment classifications, it is difficult to identify precisely what aspects of parental behaviour are important. Some studies identify warmth but not sensitivity; some, patterning of stimulation but not warmth or amount of stimulation, and so forth. There is a general belief, however, that insecure-avoidant attachments are associated with intrusive, over-stimulating, rejective parenting, whereas insecure-resistant attachments are linked to inconsistent, unresponsive parenting (Belsky, 1999; de Wolff and van IJzendoorn, 1997).

Although the associations with disorganised (Type D) attachments are less well established, Type D attachments are more common among abused and maltreated infants, and among infants exposed to other pathological caregiving environments (Lyons-Ruth and Jacobvitz, 1999; Teti et al., 1995), and may be consequences of parental behaviours that infants find frightening or disturbing (Main and Hesse, 1990; Schuengel et al.,1999). There is also increasingly strong evidence that genetic factors are implicated in disorganised attachment (Gervai, 2009).

4.1 Sensitivity

Sensitive parenting – that is, nurturant, attentive, non-restrictive parental care – and harmonious infant–parent interactions are associated with secure (Type B) infant behaviour in the SST, and this appears to be generally true of infants in a range of cultures (de Wolff and van IJzendoorn, 1997; Posada et al., 1999; Thompson, 1998). Infants who are classified as either insecure-avoidant (Type A) or insecure-ambivalent (Type C) are more likely to have parents who over- or under-stimulate, who fail to make their behaviours contingent on infant behaviour and appear cold or rejecting, and who sometimes act ineptly.

4.2 Emotional communication

One aspect of parenting behaviour that appears to be linked to attachment security is the expression of emotion, and emotional responses by both parents and infants.

Research summary 2: Emotional communication and attachment

Goldberg et al. (1994) analysed 30 video recordings of the SST, gathered in a longitudinal study of Canadian children. The recordings were selected to ensure that ten secure, ten insecure-avoidant and ten insecure-ambivalent relationships were included. The three groups were matched for infant gender, age at testing, and parent age, occupation and education. The analysis of the video tapes focused on recording and coding emotional events in the infants’ experience (smiles, whines, cries, etc.), and on mothers’ responses to these events.

First, it was found that insecure-ambivalent infants showed the highest frequencies of emotional events, followed by secure infants, with insecure-avoidant infants showing the fewest. There were also significant differences in the relative proportions of different types of emotional events: secure infants showed roughly equal proportions of positive, neutral and negative events, avoidant infants engaged in few negative events, and ambivalent infants showed high levels of negative emotion.

Taking into account these differing proportions of infants’ emotions, the mothers of secure infants responded most frequently to their infants’ emotions, and to all types of emotional event. Mothers of ambivalent infants responded rather less frequently overall, but a higher proportion of their responses were to negative affect; they rarely responded to positive emotions. Mothers of avoidant infants responded least often, and particularly infrequently to their infants’ negative emotions.

To summarise, secure infants showed a full range of emotions and their mothers responded to all of these; the dyads showed rich, full emotional exchanges. It could be said that the infants were learning that all emotions are ‘valid’ in relationships. The avoidant infants showed few emotions, and were especially muted in showing negative emotions. Their mothers were similarly unresponsive, especially to the very few negative emotions their infants showed. These infants seemed to be learning to suppress emotionality in general, and particularly to suppress negative feelings. The ambivalent infants showed a lot of distress, and their mothers responded especially to these displays. Ambivalent infants seemed to be learning that negative emotions get attention; that these are the ‘valid’ emotions in the relationship.

These results show clearly how mothers’ differential sensitivity to their infants’ emotional communications, and to the positive and negative emotions, can be an important factor leading to infants developing different types of internal working models of relationships. This confirms Ainsworth’s fundamental observations made during her pioneering studies (Ainsworth, 1969) as described earlier.

4.3 Mind-mindedness

Bretherton et al. (1981) and Fonagy and Target (1997) have suggested that the ability to understand that people have mental states is linked to the ability to develop a representation of self that is a component of the internal working model concept. Fonagy and Target suggest that this ‘reflective function’ serves as a basis of later social understanding, emerging as a natural consequence of generalisations from the early attachment relationship.

Research summary 3: Maternal mind-mindedness and attachment

Elizabeth Meins and her colleagues (Meins et al., 2001) carried out a study of 71 mothers and their infants where, as well as Strange Situation assessments of the infants when they were aged 12 months, data were also collected earlier when the infants were 6 months old. In this first set of sessions, the mothers’ behaviour and talk to their infants during a 20-minute free-play episode, with a range of toys available, were video recorded and subsequently analysed. As well as coding for maternal sensitivity, using a method devised by Ainsworth (Ainsworth et al., 1971), the recordings were analysed to find out the proportions of mothers’ utterances and behaviours that made clear reference to their infants’ mental states. It was found that the mothers of infants who were assessed as securely attached used substantially more of such references. Although the sensitivity codings also predicted attachment security, the latter measures were more powerful, suggesting that parents’ communication styles may be a crucial aspect of the transmission of attachment.

Describing parents who treat their children as ‘persons’, with thoughts and feelings, as ‘mind-minded’, Meins has argued that such parents tend to ‘treat their infants as individuals with minds, rather than merely entities with needs that must be met’ (Meins et al., 2001, p. 332), exposing infants and toddlers to more talk about psychological constructs. From this perspective, exposure to mental-state language and secure attachment are closely linked. Meins et al. (2002), in a subsequent study of 57 mother–infant pairs, looked at mothers’ mind-mindedness when the infants were 6 months old. They also collected data on how well these infants were subsequently able to perform on a range of tasks assessing the capacity to think about other people’s beliefs (so-called ‘Theory of Mind’ tasks). They found that the more mothers’ language made reference to and commented on their 6-month-old infants’ minds, the better the children’s performance on the theory of mind tasks at age 4.

Subsequent research by Meins and her colleagues has clarified a distinction between maternal sensitivity and mind-mindedness:

… appropriate mind-related comments and maternal sensitivity appear to assess distinct facets of infant–mother interaction. For example, imagine an infant begins to cry and reach up his or her arms when the mother walks away to get something from the other side of the room, resulting in the mother returning to comfort the child. This response would appear to be sensitive and socially contingent, but in the absence of the mother voicing her reasons for returning to comfort the child, it is impossible to establish whether the response is mind-minded. If, while comforting the infant, the mother remarks that the child is crying because he or she did not want her to leave or wished she would come back, these would be classified as appropriate mind-related comments. However, if the mother comments that the child is crying because he or she is angry with her or bored, these comments would be classified as nonattuned because they appear to misinterpret the infant’s likely internal state. Focusing on mind-related discourse thus provides crucial information on the mother’s psychological orientation toward her child.

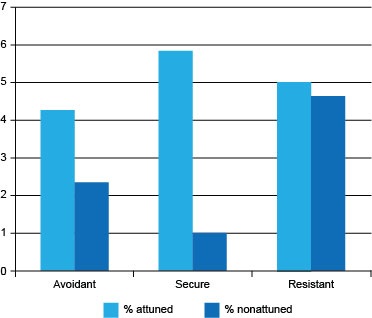

Developing this concept of ‘attunement’ has allowed more detailed investigation of the links between attuned and nonattuned comments made by mothers on their infants’ mental states. In a study of 206 mothers with their infants (Meins et al., 2012), it was found that these two types of comments appear to have independent effects on attachment security. As shown in Figure 12, a higher proportion of attuned comments was associated with a secure infant attachment classification, and a lower proportion of nonattuned comments was also a predictor of secure attachment. The chart also shows that very high proportions of nonattuned comments predict resistant attachment, more than avoidant.

This is a histogram chart. It has three sets of two bars. The first set shows the percentages of attuned and nonattuned comments made by mothers of avoidant infants. For attuned responses the percentage is 4.26 and for nonattuned it is 2.36. The next set of bars shows 5.85 per cent attuned responses and 1.01 per cent nonattuned responses for mothers of secure infants. The last set of bars shows 5 per cent attuned and 4.66 nonattuned responses by mothers of resistant infants.

5 Stability of attachment into later childhood

Predictions of subsequent development from Strange Situation attachment classifications are far from perfect, regardless of which attachment type is concerned (Lamb et al., 1985; Thompson, 1998). Rather, the predictive relationship between Strange Situation behaviour in infancy and subsequent child behaviour is found only when there is stability in caregiving arrangements and family circumstances, which maintain stability in patterns of parent–child interaction. This raises the interesting question of whether the prediction over time is attributable to individual differences in the quality of early infant–parent attachments or instead to the continuing quality of child–parent interactions over time? The latter would imply that the quality of early relationships was predictively valuable; not because it caused later differences directly, but because it presaged later differences in the quality of relationships that in turn support continuing differences in the child’s behaviour. Such a pattern of findings would suggest that stability in attachment is a consequence of stability in parent–child interactions and some evidence has been found that supports this (Belsky and Fearon, 2002).

5.1 Genetic and environmental influences

Until quite recently, the dominant view of attachment formation has been an environmental one, stressing the causal factors of sensitivity and other aspects of caregiving. However, while the evidence has stacked up for these environmental causes of differences in attachment relationships, the ‘strength of effect’ of these causes has consistently been shown to explain only part of the differences. For example, a meta-analysis of the effect size for maternal sensitivity has estimated that only about one-third of the variance in attachment security can be explained by variance in maternal sensitivity. Other factors such as emotionality and emotional responsiveness, and mind-mindedness, have additional effects, and a ‘cumulative risk’ model is now emerging for poorer attachment outcomes in which factors such as these and socio-economic factors have additive effects. But even with these additive effects, there is still variation among children’s attachment outcomes which cannot be explained by environmental variation. There is now an increasing interest in genetic differences in children and how these may also be significant influences on outcomes.

Disorganised attachment has been a particular focus of research in respect of the contributions that genetic variation and differences in caregiving environment make to the development of this outcome, which has negative consequences for children’s subsequent adolescent and adult life. While this is a relatively new and dynamic field of research, it has already shown the complexity of the mechanisms that underlie attachment disorganisation, and has provided some new insights into how genes and environments appear to interact in development.

5.2 Interventions to enhance attachment security

Not surprisingly, given the associations between secure attachment and positive outcomes for children, many initiatives have been taken to seek to enhance parenting, where parents are seen to need outside help, in order to improve attachment security. Given the consensus among many researchers that maternal sensitivity is one of the most important factors influencing attachment, most interventions have focused on this as a target, although the methods used vary widely, and there are several different programmes which have been shown to be effective (Oates, 2010). A meta-analysis of 81 research studies of intervention programmes (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2003) found that the more successful programmes were indeed targeted on sensitivity, that these were effective in enhancing sensitive responding, and, most importantly, that the expected improvements in attachment security also followed. This analysis further found that these gains were not necessarily dependent on long-term work with parents, but that short-term programmes (of 5–16 sessions), where these focus clearly on parental behaviour, can be successful.

6 Strange Situation Test

The Strange Situation Test is a standardised assessment of a child’s attachment status, which is normally carried out when a child is aged between 9 and 18 months of age. The following two videos show examples of this method being carried out in the laboratory of the Childhood and Youth Studies Group on The Open University’s Milton Keynes campus.

Making a valid classification of a child’s attachment on the basis of videos such as these is a highly skilled task, requiring extensive training to reach a high degree of accuracy and reliability. For this reason, do not view these videos with an aim of assessing each child’s status. Rather, make use of them to better understand the method and, in particular, the reunion behaviour that is analysed.

Now view the videos below.

Transcript: Strange Situation Test 1

[CHILD COOS]

[KNOCKING]

[KNOCKING]

[CHILD SHRIEKS]

[CHILD CRIES]

[KNOCKING]

[CHILD CRIES]

[CHILD CRIES]

[MOTHER GENTLY SHUSHES]

[CHILD SHRIEKS]

[KNOCKING]

[CHILD CRIES MOMENTARILY]

[PROLONGED CRY]

[PROLONGED CRY]

[CRYING CEASES]

[SINGLE CRY]

[CRYING]

[CRYING]

[CRYING]

[KNOCKING]

Transcript: Strange Situation Test 2

[KNOCKING]

[KNOCKING]

[KNOCKING]

[KNOCKING]

[KNOCKING]

[CHILD CRIES MOMENTARILY]

[CRIES]

[CRIES CONTINUOUSLY]

[KNOCKING]

You may be concerned about the ethics of these tests. The protocols that are followed have been developed over many years to minimise and mitigate children’s distress and the two separation episodes are terminated as soon as either the carer or the supervising researcher feels that the stress may become too much for a child to cope with.

Conclusion

Children have a basic, evolved need for attachment to other individuals who can provide security as well as supplying physical needs such as food, warmth, clothing and shelter. Children can and do form multiple attachments with those people around them who provide ongoing care. Secure attachments are based on sensitive, emotionally responsive and attuned carer behaviours, and are associated with positive developmental outcomes. Finally, based on their experiences with those who care for them, children construct mental representations of what it is to be in a relationship with another.

Glossary

- Attachment

- A focused, enduring and emotionally meaningful relationship between two people, characterised by seeking to gain or maintain proximity through physical contact or communication. Mother–infant attachment is an important concept in Bowlby’s theory of maternal deprivation. The Strange Situation Test (SST) is one way of assessing whether an infant has formed a secure or an insecure attachment with the caregiver.

- Cognition

- A general concept concerned with all forms of knowing: for example, attention, perception, memory and thinking.

- Conservation

- In Piaget’s theory this refers to the understanding that quantities remain the same despite transformations (e.g. the volume of a liquid remains the same, irrespective of the shape of the container). Young children’s inability to understand this is considered by Piaget to show egocentrism.

- Environment of evolutionary adaptiveness (EEA)

- In evolutionary psychology this refers to the environment of our hominid ancestors, which has shaped the psychological mechanisms present in modern humans, through the process of selective pressure.

- Ethology

- The study of animal behaviour in the natural environment and, in particular, the ways in which certain behaviours may be adaptive in terms of promoting survival. Imprinting is an example of such behaviour.

- Imprint

- A term used in ethology to describe a phenomenon observed in some species of bird where the young, soon after hatching, have a strong tendency to become attracted to a particular moving object and thereafter to follow it. Bowlby drew a parallel between imprinting and mother–infant attachment, and this idea was influential in his theory of maternal deprivation.

- Internal working model (IWM)

- The term used by Bowlby to suggest that infants form representations of relationships early in life based, in particular, on the relationship with the primary caregiver. There are three elements: a model of the self, a model of ‘the other’ and a model of the relationships between the two. The IWM developed in infancy forms a template for future relationships, although some modification is possible.

- Mind-mindedness

- The ability to understand the mental states of others, which is specifically used to describe caregivers who treat their infants as individuals with minds, rather than merely entities with needs that must be met. There is some evidence for a link between a mother’s mind-mindedness and her infant’s development of theory of mind. It is one component of maternal sensitivity.

- Natural experiment

- A study in which researchers take advantage of naturally occurring events, rather than themselves manipulating variables. Twin studies are an example.

- Strange Situation Test (SST)

- A research method carried out in a laboratory playroom. The child, with its mother, is confronted with an adult who they have never seen before and is then left by the mother with this stranger, before being left entirely alone. The child’s responses to this series of increasingly stressful events are observed. The child is then reunited with the mother. This method has been widely used in attachment research and particularly in research that focused on individual differences. It has been criticised for its lack of ecological validity, the failure to take into account the mother’s behaviour and its narrow data base.

- Stress

- An imbalance between a person’s perception of the demands a situation makes of them and their perceived ability to cope with it.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by John Oates.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated in the acknowledgements section, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

Course image: Pablo in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Images:

Figure 1: © The Open University

Figure 2: © Getty Images/Getty Images

Figure 3: © Getty Images

Figure 4: © Getty Images

Figure 5: © iStockphoto

Figure 6: © The Open University

Figure 7: © Alamy

Figure 8: © Richard Bowlby

Figure 9: © iStockphoto

Figure 10: © John Oates

Figure 11: © The Open University

Figure 12: © The Open University.

AV

© The Open University

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2018 The Open University