Introducing ageing

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 1 December 2025, 6:24 PM

Introducing ageing

Introduction

Have you ever thought about how long you might live? In the UK and in many other parts of the world, most people can expect to live longer than their parents and grandparents did. A baby born in 2011 is almost eight times more likely to live to be 100 than one born in 1931 (Department of Work and Pensions, 2011). The World Health Organization estimates that globally the proportion of people aged over 60 will double from 11% in 2000 to 22% in 2050 (WHO, 2012). These big changes can have really significant effects on individuals and on society more widely.

Image showing four headlines as follows:

- Britain’s population timebomb: By 2060 there’ll be just two workers for every pensioner

- Facing the challenge of an ageing population

- Taxpayers would bear the brunt of free care for pensioners

- Woeful preparation for ageing population will cause misery, say Lords.

You may have seen headlines and comments like these yourself. But is this really the whole story? Do older people necessarily make greater demands on health care services? Shouldn’t we be celebrating the fact that most people are living longer? What about the quality of life people experience during these additional years? Isn’t it ageist to categorise all older people as nothing but drains on society? What about the contributions older people make to society? Asking lots of questions about something that is often taken for granted is an important part of what it means to approach a topic in an academic way. This course will help you to explore the topic of ageing in this way.

Core questions

- How is growing older in the 21st century different from growing older in the past?

- What is meant by ‘the Third Age’?

- What is meant by ‘the Fourth Age’?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of categorising older people in this way?

- How have your own experiences of ageing so far influenced the way you approach this topic?

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course K118 Perspectives in Health and Social Care.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

demonstrate knowledge and understanding of current issues in ageing and later life

reflect on experiences of ageing and later life

analyse case studies of care situations, drawing out their wider relevance to concepts and ideas

demonstrate developed literacy, numeracy, and digital and information literacy skills.

1 Thinking about your own ageing

We are all ageing from the moment we are born and most of us will be old one day. Particular events often make people suddenly aware of their own ageing – round number birthdays, for example, the first grey hair, or retirement. How people feel about their own ageing can vary hugely, depending on many different factors such as how generally happy they are with their lives, how much longer they expect to live, the older people they know and the ideas about ageing they have picked up from their wider culture.

Three pictures of a womans face, where the woman ages gradually across the three pictures from young to elderly.

In Activity 1 you are going to reflect on your own experiences of ageing so far, whether you think of yourself as currently ‘young’, ‘old’, ‘middle-aged’ or ‘ageless’.

Activity 1 My own ageing

Write a paragraph about your own experiences of ageing so far. You could write about:

- whether you feel the same age as your age in years (your chronological age)

- how you would describe your current age

- how other people affect your sense of your own ageing

- how changes to your body make you aware of your ageing

- what you are looking forward to about growing older

- what you fear about growing older.

Comment

Here is what one person wrote:

I was 41 last birthday and that feels about the right kind of age for me. Some days I feel much older, when I’m tired and I look in the mirror and see nothing but bags and wrinkles and grey hairs. And some days I forget I’m not still about 30. My parents are from Bangladesh and I was brought up to be quite respectful of old people. I think that probably makes me feel a bit more positively towards my own ageing because I have this idea in the back of my mind that being old means being wise and important (even though I can’t really envisage myself ever being like my grandmother who’s nearly 90!). I’m looking forward to having fewer responsibilities after my kids leave home and hopefully not being so busy after I have retired. I worry about getting dementia and having strangers coming in to my home to help me.

Reflecting on your own experiences of ageing is an important part of the academic study of ageing and later life because it affects the ways you approach the topic. Most people do not feel completely neutral about the topic of ageing. It is often difficult for people to imagine that they will ever really be old themselves (Jones, 2012). It is also very common for people who would generally be categorised by other people as ‘old’ to speak as if they were not old – to disassociate themselves from being old. Gerontologists (people who study ageing and later life) have been interested in why this happens, and come up with several different explanations (Bultena and Powers, 1978; Jones, 2006). However they tend to agree that the underlying reason is that we live in an ageist society – one which associates being old with being useless, redundant and of low value. It is therefore not surprising if people do not want to think of themselves as currently old or admit that they will one day be old.

The word ‘ageism’ was coined by Robert Butler:

Ageism can be seen as a process of systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against people because they are old, just as racism and sexism accomplish this for skin colour and gender. Old people are categorized as senile, rigid in thought and manner, old-fashioned in morality and skills … Ageism allows the younger generation to see older people as different from themselves, thus they subtly cease to identify with their elders as human beings.

You will return to the topic of ageism later in this course. But is being ‘old’ always a tale of decline, decrepitude and difficulty? This is the issue you will explore in the next section.

2 Introducing Monty Meth

In Activity 2 you will be introduced to Monty Meth, an 87-year-old man living in London. Thinking about issues through individual case studies can be a good way to start exploring ‘the bigger picture’. Case studies also help us to work through questions that are relevant for other people, in different situations.

Activity 2 A day in the life of Monty Meth

Part 1

Watch Video 1. You might find it helpful to watch it through twice – all the way through to begin with, and then again, pausing it whenever you want to make notes.

Transcript: Video 1 A day in the life of Monty Meth

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

[LAUGHTER AND INDISTINCT VOICES SPEAKING]

[COMPUTER CHORD]

Then answer the following question:

How does Monty’s life compare to yours? What is different and what is similar?

Fill in Interactive table 1 using the first column for yourself and the second column for Monty. This will help you to think about the significance (or not) of your age and Monty’s age.

Please note: At this point you do not need to write anything in the third column (titled ‘Molly Davies, age 90’). It forms part of a later activity.

| Name / Age | Monty Meth, age 87 | Molly Davies, age 90 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living situation | |||

| Health | |||

| Family responsibilities | |||

| Paid work | |||

| Unpaid work | |||

| Social life | |||

| Busyness | |||

| Satisfaction with life |

Comment

Here is what one person wrote:

| Me, age 41 | Monty, age 87 | |

|---|---|---|

| Living situation | With my partner and her three kids. | Lives with his wife; children have grown up and left home. |

| Health | Okay. I seem to get constant colds and coughs, especially in the winter – think the kids bring them home from school. | Really good for his age! Goes swimming every morning. |

| Family responsibilities | The kids – looking after them practically and financially. | Does not mention any family responsibilities. His wife seems to be as healthy and active as Monty, so she does not seem to need any looking after. |

| Paid work | Full time. | Does not do any paid work. |

| Unpaid work | None except helping out at the kids’ school events sometimes. Unless you count looking after the kids! | Does lots, especially through the Enfield Over-50s Forum. |

| Social life | Not much! Can never get a babysitter. Sometimes go to the pub on a Friday night. | Seems very friendly with the group of people he swims with every day. Mentions going to the theatre. It seems likely that his work with the Enfield Over-50s Forum has sociable aspects. |

| Busyness | Too busy a lot of the time – there is just too much to fit in. | Seems very busy – he goes swimming every morning as well as all the other things. |

| Satisfaction with life | Fairly satisfied but I would like to have more time to do things for me, and more time to spend with my partner without the kids around. | Seems very satisfied with his life. |

Part 2

Now think about two adults that you know personally, one younger than you and one older than you. Filling in Interactive table 2 will give you two more people to compare with your own and Monty’s experiences, which will give you further information about the significance of age

| Younger Adult / Age | Older Adult / Age | |

|---|---|---|

| Living situation | ||

| Health | ||

| Family responsibilities | ||

| Paid work | ||

| Unpaid work | ||

| Social life | ||

| Busyness | ||

| Satisfaction with life |

Comment

And here is what the same person wrote in the second table:

Younger adult My step-brother, aged 28 | Older adult My mum, aged 61 | |

|---|---|---|

| Living situation | With my mum. | With my step-brother. |

| Health | Has asthma – mostly seems to be okay though. | Fine. |

| Family responsibilities | None, as far as I know. | Still doing the laundry, cleaning and cooking for my step-brother. |

| Paid work | Sometimes. He never seems to manage to keep jobs for long. | Works part-time at a garden centre. |

| Unpaid work | None, as far as I know. | Is ‘Brown Owl’ of her local Brownie group and secretary of local Gardening Club. Takes a neighbour shopping every week. Visits my Gran in the care home twice a week. Helps a friend with her garden. |

| Social life | At the pub or out clubbing most nights. Also goes on holiday with a group of friends every year. | Loads – goes walking with a group of friends most weeks, goes to a pilates group, goes out for meals with friends and goes on holiday with them most years. |

| Busyness | Not very busy. | Pretty busy, but do not think she feels ‘too busy’ like I do. |

| Satisfaction with life | I do not think he is actually very happy with his life. I know he would like his own place but cannot afford it. | Pretty happy. I know she gets a bit fed up with looking after my step-brother sometimes but she also says she likes his company. She had a tough time after my step-dad left, but she seems to have come through that now and to enjoy her life. |

Although Monty is presumably coming to the end of his life, he is very far from being the burden on health and social care services that the newspaper headlines predict. Indeed he seems to be contributing more to society than some younger people. He also seems to find his life enjoyable, satisfying and meaningful. So how can we explain the mismatch between Monty’s experiences and the fears people have of what it means to have an ageing population? Is Monty just really unusual or really lucky? In other words, is he typical of older people, or atypical? In the next section you will look at one answer to this question which has had a very significant influence on people working in the field of ageing.

3 Introducing ‘the Third Age’

Peter Laslett (1915−2001) was an academic with wide-ranging interests including social history, politics and ageing. He was one of the founders of the University of the Third Age (U3A) (and also helped to establish The Open University). In 1989 he published a very influential book called A Fresh Map of Life: The Emergence of the Third Age (Laslett, 1989a), which you will look at in more detail in Activity 3.

Activity 3 A fresh map of life

Reading 1 - (a)

Click on the following link to read Reading 1 A new division of the life course (Laslett, 1989b), which is an extract from Laslett’s 1989 book.

Now, answer the following questions to check your understanding of what Laslett is arguing:

- a.In what ways does Laslett say that our modern ideas about ageing are influenced by what happened to older people in the past?

Comment

Laslett argues that in the past most people did not live to be old and we still have not really got used to the idea that people are living much longer nowadays. He says that in the past a greater proportion of older people experienced poor health and frailty and our ideas have not caught up with the fact that many older people now experience good health. This means that we still associate old age with frailty when this is no longer so common.

Reading 1 - (b)

- b.Write in your own words a brief description of the First, Second, Third and Fourth Ages.

Comment

You may have come up with something similar to the following:

- First Age – childhood, dependence and education.

- Second Age – younger and middle-aged adulthood, while people are generally working and raising families.

- Third Age – after people have generally stopped working and any children have left home.

- Fourth Age – once people are frail and dependent.

Reading 1 - (c)

- c.If people in the Third Age are healthy and active, how is the Third Age different from the Second Age?

Comment

The Second Age is a time when adults generally have lots of responsibilities to earn money and look after their families. In the Third Age they are much freer to pursue activities that they find personally fulfilling.

Reading 1 - (d)

- d.At what age do people generally enter the Fourth Age?

Comment

Laslett argues that there is no connection between someone’s chronological age (how old they are) and which stage of life they are in. Some people might enter the Fourth Age in their 60s or 70s, or even earlier, others not until their 90s or older. Or they might die suddenly, for example falling under the proverbial bus, while still in the Third Age.

Reading 1 - (e)

- e.What benefits does Laslett argue come from reconceptualising later life as having two distinct stages, the Third Age and the Fourth Age?

Comment

Laslett says that recognising the Third Age as a distinct stage has many benefits: it is a better reflection of most people’s lives in the developed world today; it helps us recognise that most people over retirement age are healthy and active; it is more optimistic for individuals who may be worried about their own ageing; it helps ensure the talents, experience and energies that older people have do not go to waste.

As Laslett himself acknowledges, there have always been some healthy and active people in their 70s, 80s and even older. But Laslett is arguing that this is now so common that we need to rethink our expectations about what is likely to happen over the course of someone’s life. Instead of thinking of life as falling into three main stages – childhood, adulthood and old age – we need to think of four. Rather than seeing healthy, active older people as exceptional, we need to recognise that many people can reasonably anticipate years of fulfilling life after they have finished paid work and any children have left home.

Characterising the Third Age

You may already have thought of some objections to Laslett’s argument – is having a Third Age a lot to do with how much money you have got and how healthy you are, for example? What about people with disabilities or long-term conditions? Is this way of dividing up the life course a bit dismissive of people in the Fourth Age? These kinds of reactions are an important part of developing an academic critique. For the moment, just make a note of any disagreements or objections you might have to Laslett’s argument – we will return to these later.

So how does Laslett’s theory help explain Monty’s experiences? In Activity 4 you will think about this.

Activity 4 Monty’s Third Age

Third Age - (a)

If you need to, go back to Activity 2 and watch Video 1 again to remind yourself about Monty’s experiences. Then answer the following questions:

- a.What examples in Monty’s life seem to fit Laslett’s characterisation of the Third Age?

Comment

Monty is very active and enjoys good health. He is certainly contributing to society through his work for the Enfield Over-50s Forum. He also seems to find his various activities rewarding and fulfilling. He does not seem to be in a period of his life characterised by decline and difficulty. Rather, he seems to be enjoying a full and varied life without the responsibilities of working or caring for family members that he had earlier in his life. Laslett argues that chronological age has very little to do with whether someone is in the Third Age or not, so Monty’s age does not preclude characterising him as being in the Third Age.

Third Age - (b)

- b.What factors do you think might have contributed to Monty’s long Third Age?

Comment

We do not know definitively why Monty’s Third Age has lasted so long but it seems likely that his good health, regular exercise, relative affluence, apparently happy family situation and his own personality have all contributed.

You may agree that the Third Age seems to be quite a good description for the experiences of some individuals – perhaps you yourself if you are ‘in later life’, or other people you know, as well as Monty. But how typical are these individuals? Laslett was writing in 1989. Do his claims that most people can now expect to experience a Third Age hold up more than 25 years later? These are some of the issues that the next section explores.

4 The Third Age and population changes

To find out whether experiencing a Third Age is common nowadays, researchers need to look at lots of people’s experiences. However, they cannot just ask people ‘are you experiencing the Third Age?’ because most people would not know what that meant. They could ask them about their experiences of ageing and whether they feel they are in a period of self-fulfilment, but this would probably involve quite a lengthy explanation and lead to quite a long conversation, which would be very expensive and time-consuming to do with thousands of people. For large-scale studies, researchers generally need to ask quite straightforward and factual questions or to look at data about how long people are living and their health status. This does not exactly answer the question ‘is having a Third Age now common?’ but it may give clues that help to answer this question.

Activity 5 Statistics about ageing

Video 2 - (a)

The following animation, Video 2, presents you with some different statistics about older people living in the UK. Watch carefully, but you do not need to try to remember the exact numbers the video contains – focus on what it tells you about wider patterns in how people experience later life.

Then answer the following questions:

- a.Was there anything that surprised you in this information?

Comment

One person who studied these statistics reported, ‘I was surprised that so many families with working mothers depended on grandparents to do childcare. I was also surprised that only two-fifths (40%) of NHS money is spent on older people when they make up two-thirds (66%) of service users. This made me worry that older people were getting less good care than younger people, although there could be other reasons for this.’

Video 2 - (b)

- b.What aspects of later life do these statistics give information about?

Comment

Video 2 gives information about: satisfaction with day-to-day activities, ability to influence your own life, and ability to meet your goals; feeling contented or happy most days; and not feeling depressed. It also covers life expectancy and healthy life expectancy, life with a disability and life with a long-term illness, NHS spending on older people, care of grandchildren by grandparents and older people as informal carers.

Video 2 - (c)

- c.To what extent do these statistics seem to support the idea that most people have a Third Age?

Comment

The video seems to show that older people have higher levels of satisfaction with their day-to-day lives, control over their lives, being happy and so on than many other age groups. It shows that after the age of 65, both men and women have good health for more than half (57%) of their remaining lifespan. It also shows that many older people provide care and support for others. Taken together, the statistics certainly refute the idea that later life is inevitably a time of decline and despair. This is a key part of the idea of the Third Age. However, these statistics do not tell us whether people are feeling freer to pursue their own interests and goals than when they were younger, which is another part of Laslett’s argument.

Video 2 - (d)

- d.What further information might help you better answer the question about whether most people can expect to have a Third Age?

Comment

The video compares currently older people with currently younger people but they do not ask the older people who took part in the survey to compare this stage of life with previous ones. If you asked older people to compare their life now with their earlier life, that might give you some useful information.

Of course statistics like these are about the population as a whole – they do not tell you about a particular individual. If the average 65-year-old woman can expect 11.6 more years of good health, some are likely to experience only one more year while others some 30 more years. And of course not everyone below the age of 65 experiences good health or is without a disability. However, the statistics you have seen here do seem to support Laslett’s argument that most people nowadays can expect to experience many years of healthy and productive life after retirement. What the statistics here do not really tell you is whether this Third Age is also a time of self-fulfilment and freedom for most people.

A key academic skill is reading and thinking critically. This means not accepting things at face value but constantly asking yourself questions such as ‘is this really the case?’, ‘are there other possible explanations?’ or ‘how does this match up to what I already know?’ This is what you were beginning to do when you used the statistics to test out Laslett’s argument.

It is especially important to keep thinking critically when numbers and statistics appear, because many people do not feel fully comfortable with numbers, so they tend to skim over them, rather than reading them with full attention. This can mean that they do not really think about whether the numbers actually show what the author claims they do. People also tend to find numbers and percentages very convincing and persuasive, regardless of whether they are correct or not. For example, ‘63% of people living in this area are aged over 40’ sounds more authoritative and factual than ‘most people living in this area are aged over 40’. Working confidently and critically with numbers is also a very valuable skill in many employment contexts. In the next section, you are therefore going to apply and develop your critical reading skills with numbers and words to a short extract from an article in a local newspaper.

Applying the theory

Read the following article, which was featured in the Milton Keynes Citizen newspaper in 2013, and then undertake Activity 6.

MK to be OAP capital of the UK

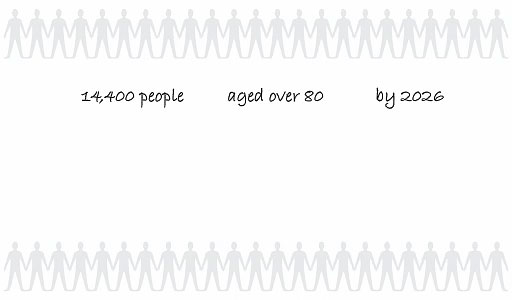

The number of people aged 80 or over living in Milton Keynes is set to double in a decade, making the city the old age pensioner capital of Britain.

New figures reveal that public services in Milton Keynes are on course to come under huge strain within a generation as the number of elderly people increases dramatically.

The statistics come from the city’s Joint Strategic Needs Assessment published by the Milton Keynes Clinical Commissioning Group and Milton Keynes Council. It shows the number of people aged 60 or over in the borough is going to increase by about 75 per cent between 2011 and 2026, from around 40,000 to 70,000. The national average is 32 per cent.

The number of people aged over 80 is set to increase by 100 per cent from 7,200 to 14,400 over the same period.

[...]

Milton Keynes has long had a reputation for being a young, vibrant city, home to thousands of young families.

However, it is the city’s very nature which has led to such a massive increase in the size of the elderly population as men and women who moved to the area in the 1960s and 70s are now nearing retirement age.

By 2026 people aged 60 or over will make up a quarter of the borough’s total population.

(Downes, 2013)

Activity 6 Going beyond the headlines

Click on the following link to access a Word version of the newspaper extract ‘MK to be OAP capital of the UK’ (Downes, 2013). Use the following questions to help you think critically about what it says..

- a.Using the highlighting tool in your word processor, or a highlighter pen if you are working from paper, choose one colour to represent statistics. Highlight all the statistics that are cited in the article. Now use a second colour to highlight all the claims that are made about what these statistics mean.

- b.The article tells us that a quarter, or 25%, of the population of Milton Keynes will be aged over 60 by 2026, but it does not tell us what percentage of the population will be aged 80 or older. Using the figures in this article, calculate this figure.

If you need a reminder of how to calculate percentages, try searching online using a search term such as ‘how to calculate percentages’. There are plenty of sources of help. If the first one you find does not make sense to you, try looking at another one.

- c.What further information would you need in order to find out whether Milton Keynes was going to be the OAP capital of the UK?

- d.What assumptions about ageing does this article make? How do the concept of the Third Age and the statistics you used in Activity 5 help to counter those assumptions?

- e.Can you think of alternative conclusions you could draw using some of the same statistics? Write the headline and first few sentences of a newspaper article giving a different spin on these figures. Do not worry too much about whether your version would really work as a newspaper article – just have a go at drawing some different conclusions.

Comment

- a.Click on the following link and open the Word document to see how one of the authors of this course has highlighted the document.

- b.Watch the following animation, which shows how you should have calculated the percentage:

Transcript: Animation 1

- c.In order to find out whether Milton Keynes was going to become the OAP capital of the UK, you would also need to know:

- What percentage of people aged 60+ and 80+ will other areas have by 2026?

- Are 25% and 5.15% actually particularly high? Is 5.15% of the population aged 80+ by 2026 an usually high proportion for a UK town, or is it quite typical?

- How reliable are these projections?

- Where do they come from and is it a reputable source?

While a 75% increase in the number of people aged over 60, compared to a national increase of 32% sounds big, if there were not very many people aged over 60 in 2013 it might not be remarkable. In the case of Milton Keynes, which, as the article suggests, has historically had quite a small population of older people, this increase could be Milton Keynes becoming more like the rest of the UK, rather than becoming the OAP capital.

You might also ask:

- What is an OAP capital?

- Is it the place with the highest proportion of people aged over 60?

- Or is it a place that many older people choose to live?

- Or is it a place that is particularly well-designed and welcoming for older people?

MK has always had a reputation as a youthful city – a new town, full of young families just beginning their lives together. But statistics just out show that with people who moved here in the 60s and 70s growing older, it’s also becoming a place for older people too. By 2026, 25% of the population is expected to be aged 60 and over, and the population of people aged over 80 is expected to double, as people live longer healthier lives.

- Other headlines could be ‘Milton Keynes citizens are living longer!’ or ‘Milton Keynes is getting older and wiser!’ or ‘Volunteer army at the ready to help us all!’

Apocalyptic demography?

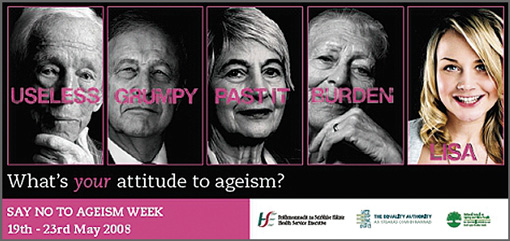

The article you just read could be seen as an example of what some gerontologists have termed ‘apocalyptic demography’ – that is, treating people living longer solely as a problem and burden to societies with terrible long term effects (Bytheway and Johnson, 2010). Rather than celebrating the fact that many people are living longer, and recognising the benefits that having more older people in the population might bring, apocalyptic demography focuses only on the negatives. An ageing population undoubtedly changes society and creates new challenges but it is both over-simplistic and ageist to frame this only as a problem. You may remember that part of Butler’s original definition of ageism was that it involved ‘systematic stereotyping’. As one commentator says:

The apocalyptic picture of the future is indeed ageist, because it objectifies people who are ageing and treats them as though they are all alike. They are not people anymore; they are ‘the burden’. From this negative point of view, these older people are not capable of contributing creative solutions to meeting their own needs. They have no agency. They are inert, the burden. The sky is falling, and it is falling because there are too many older people. That sounds ageist to me.

(Longino, 2005, p. 79)

One of the ways ‘isms’ like racism, sexism and, here, ageism, work is by over-generalising and stereotyping, as if everyone who can be categorised in a particular way is the same as everyone else in that category. Laslett’s concept of the Third Age can help to resist apocalyptic demography by making it clear that ageing is not simply about decline, dependency and difficulty.

This image is a poster for ‘Say No To Ageism Week’. It shows five images, left-to-right, of people’s faces. The first four images are in black and white and show older people. Over their faces are the captions ‘useless’, ‘grumpy’, ‘past it’ and ‘burden’. The right-hand image is in colour and shows a young woman. Below her face is the caption ‘Lisa’. Beneath the pictures is the question ‘What’s your attitude to ageism?’

Laslett’s argument about the growth of the Third Age is an example of an academic theory. Theories take a complex social phenomenon (in this case, ageing) and attempt to understand it more clearly by carrying out research and by developing explanations, categories and concepts. Theories can make things look simpler and more tidy than they actually are. Reality is usually messy and very complex, so no theory is perfect and explains everything. However, a useful theory takes you beyond what you already think you know and helps you to see things that you otherwise might not. That is why developing and refining theories is a key part of academic work.

One of the ways in which theories are developed is by other people reading and responding to the original theory. Laslett’s theory of the growth of the Third Age has been very influential and many people have developed and also criticised his ideas. While there is broad agreement that more people are living longer, healthier lives, some gerontologists have argued that Laslett’s emphasis on self-fulfilment in later life is unhelpful because it puts too much emphasis on personal achievement (Gilleard and Higgs, 2002). This can make it seem that, if people do not experience a Third Age, it is somehow their fault when, actually, their socio-economic circumstances or a combination of unlucky events are the main cause. Another common criticism is that the idea of the Third and Fourth Ages is rather unhelpful when thinking about people who are more dependent and frail. It is this issue that the next section focuses on.

5 What about the Fourth Age?

This photograph shows a group of older men sitting in wheelchairs which seem to have been abandoned in the middle of nowhere. Some of the men are flopped over as if they are asleep or unconscious.

In Activity 7 you are going to begin thinking about the Fourth Age by meeting Molly Davies, who lives quite a different life from Monty Meth.

Activity 7 A day in the life of Molly Davies

Click on the following link to watch Video 3 through twice, as before, and fill in Interactive table 3 to compare Molly’s life with the comments you made about your own and Monty Meth’s in Activity 2. You will see the comments you made about yourself and about Monty previously are filled in below.

Transcript: Video 3 Molly’s story

Video 3 Molly’s story

[CLOCK TICKING]

[PHONE RINGING]

[INDISTINCT FEMALE VOICE ON PHONE]

[INDISTINCT FEMALE VOICE ON PHONE]

| Name / Age | Monty Meth, age 87 | Molly Davies, age 90 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living situation | |||

| Health | |||

| Family responsibilities | |||

| Paid work | |||

| Unpaid work | |||

| Social life | |||

| Busyness | |||

| Satisfaction with life |

Comment

Here is how one person filled in the table:

| Monty Meth | Molly Davies | |

|---|---|---|

| Living situation | Lives with his wife, children have grown up and left home. | On her own with paid carers coming in four times a day. |

| Health | Really good for his age! Goes swimming every morning. | Pretty poor. She mentions being in pain at night and whenever she is not in her chair. She cannot see well or hear properly. She has arthritis in her neck. She cannot get herself dressed, washed or fed without help. |

| Family responsibilities | Does not mention any family responsibilities. His wife seems to be as healthy and active as Monty, so she does not seem to need any looking after. | Does not mention any. |

| Paid work | Does not do any paid work. | None. |

| Unpaid work | Does lots, especially through the Enfield Over-50s Forum. | None. |

| Social life | Seems very friendly with the group of people he swims with every day. Mentions going to the theatre. It seems likely that his work with the Enfield Over-50s Forum has sociable aspects. | Not much. A friend sometimes takes her out in a wheelchair and you could see from the card she was writing that she had a visitor named ‘David’ recently. She describes her hairdresser as having become a friend, and goes to the hairdresser about every fortnight. |

| Busyness | Seems very busy – he goes swimming every morning as well as all the other things. | Not at all busy. |

| Satisfaction with life | Seems very satisfied with his life. | She says she loves flowers and enjoys looking at the ones in colours she can still see. She loved reading but finds it hard to do now. She does not seem unhappy with her life, but most of the things she says she likes she cannot really do anymore. |

Although Molly is only three years older than Monty, her life looks quite different. Her health is poor, she is in pain a lot of the time, she rarely goes out of the house and she needs quite a lot of help with everyday tasks like getting washed and preparing food. Molly, unlike Monty, does not seem to be in the Third Age. In Laslett’s terms she might be described as in the Fourth Age of decline towards death.

In some situations, it is useful to have a terminology to distinguish between people like Molly and people like Monty. As Laslett argues, it is important not to characterise everyone in the later stages of life as needing extensive support and having serious health issues. However, when you look more closely at the lives of people in the Fourth Age, like Molly, Laslett’s simple description of decline, dependency and decrepitude can seem a bit crude and possibly even a bit insulting to the individuals living those lives.

Studying the Fourth Age

Activity 8 is based on a study of people in the Fourth Age where the researchers found that the reality of people’s lives was much more complex than the rather stereotyped view of this stage in life that you encountered in the Laslett reading.

Activity 8 Living in the Fourth Age

Reading 2 - (a)

Click on the following link to read Reading 2 Hearing the voices of people with high support needs (Katz et al., 2013).

- a.Copy and paste below, three sentences or parts of sentences from the article that do seem to fit well with Laslett’s version of the Fourth Age.

Comment

There are several sentences you could have chosen including:

- ‘Most participants emphasized that they were simply living day to day, and hoping that no further deterioration in their physical or mental health would occur (and in some cases dreading it)’

- ‘Many participants were coping with several, often complex, health problems and described how their illnesses or disabilities had impacted on their daily lives’

- ‘a retired professor was despondent that his memory appeared to be deteriorating markedly in his seventies’

- a quote from June: ‘last time I went with the guild to the theatre it was absolute agony getting up and down from the seats… I like to do all these things, but I just can’t…’.

Reading 2 - (b)

- b.Copy and paste below, some of the sources from the article of self-fulfilment that participants experienced.

Comment

- There are lots of sources of self-fulfilment mentioned throughout the article. Examples include: ‘meaningful relationships’ with families, friends and carers, including making new friends; attending day centres; watching television programmes on topics they were particularly interested in (like travel); listening to music; continuing membership of a church; accessing nature despite not going outside.

Reading 2 - (c)

- c.In what ways did some people continue to make a contribution to society?

Comment

- Some of the examples mentioned included being a caller at bingo, making music, taking on formal roles within their community, such as committee membership, and producing theatrical shows.

Reading 2 in Activity 8 shows that, while being more frail and dependent usually reduces people’s scope to do things that they find fulfilling and to contribute to society, it does not do so absolutely. Clearly the people in Katz et al.’s 2013 study are living very different lives from Monty Meth, but it is not a simple story of decline and despair, as Laslett’s version of the Fourth Age might seem to suggest.

Neither is the boundary between being ‘Third Age’ and ‘Fourth Age’ as clear and as impermeable as it might sound. People may move in and out of the Fourth Age (Midwinter, 2005), for example if they are in remission from cancer. Some gerontologists have suggested that the trouble with Laslett’s idea of the Fourth Age is that he was not really interested in it – his focus was on making the case that people should recognise the existence and significance of the Third Age. This means that the Fourth Age works as a kind of black hole (Gilleard and Higgs, 2010). People fear it and focus on the Third Age and what it might mean to age well when you are healthy and independent. The Fourth Age then becomes a kind of residual space that sucks in everything that people do not want to think about. This means that people who are categorised, usually by other people, as in the Fourth Age can be seen as completely different and ‘other’ from most people and this can mean that they are treated less well (Grenier, 2012).

Part of the definition of ageism at the beginning of this learning guide was ‘Ageism allows the younger generation to see older people as different from themselves, thus they subtly cease to identify with their elders as human beings’ (Butler and Lewis, 1973, p. 35). You could argue, then, that Laslett’s theory of the Fourth Age contributes to ageist attitudes towards some older people, even though the theory of the Third Age helps to break down ageist attitudes towards others.

As Molly Davies and Reading 2 suggest, people who might be categorised as living in the Fourth Age remain recognisably the same as younger, healthier people. They may have greater needs for support than other people but they continue to be complex individuals with different histories, personalities, needs and preferences.

6 Reflecting on the Third and Fourth Ages

In this final activity, you will draw together what you have learned about the Third and Fourth Ages and draw your own conclusions about the advantages and disadvantages of using these concepts to think about later life.

Activity 9 Applying the ideas

Think about someone you knew reasonably well who has grown older and then died, perhaps a member of your extended family, or a colleague. Choose someone whose last years and death you do not mind thinking about – if you do not want to think about someone you knew personally, you could pick a character from a book or a film or a historical figure.

How does what happened to them map on to Laslett’s theory of the Third and Fourth Ages? Is it helpful for understanding their life or is it not very helpful? Write a short summary of about 250 words describing first the person and what happened to them and then what you think about whether Laslett’s ideas are helpful in explaining their life.

Comment

One person wrote:

I thought about my great-aunt who died a few years ago in her late 80s. Until she was 77 she had a very active kind of old age, even though she had been physically disabled all of her life. Her activities were mostly centred around her church – she ran the Mothers’ Union group, played the organ most weeks, organised a handbell ringing group and was a churchwarden. She also did lots of gardening, ran errands for a younger but frailer friend, and looked after my grandmother when she developed dementia. When she was 77, she had a series of heart attacks and subsequently experienced a lot of health problems that left her effectively bedbound. After a few years of living at home with home carers visiting several times a day, she went into a residential care home where she lived for seven years before she died.

The theory of the Third and Fourth Ages is quite helpful in understanding the disjunction between her life before and after the heart attacks. Beforehand she was contributing to society very significantly and afterwards this was much less the case. She got very depressed in this period and often talked about being a burden, so she certainly felt that she was not contributing to society. However, even before the heart attacks she didn’t experience very good health and she had been disabled all her life, so it wasn’t quite as simple as a transition from good health to poor health. And I don’t think she found her Third Age life fulfilling all the time, especially not when she was caring for my grandmother with dementia which was very difficult for her.

Conclusion

In this course, you have begun to think about the topic of ageing and later life. In particular, you have examined the idea of the Third and Fourth Ages and thought about how they can be applied to both individuals and population ageing.

Key points

- Many people growing older in the UK today can expect to have many years of reasonably healthy and active life after they reach retirement age.

- The period of life around and after retirement age is sometimes known as the ‘Third Age’ and can be a time some people find particularly fulfilling and satisfying.

- The ‘Fourth Age’ refers to the period when an older person is frailer and often dependent on other people for their daily needs.

- Categorising older people in this way can be useful because it makes it clear that being older is not the same thing as being dependent and in ill-health. This can help resist 'apocalyptic demography', which treats our ageing population as a problem, not a success.

- Some of the disadvantages of categorising people in this way are that it seems to imply that people in the Fourth Age don’t experience self-fulfilment or make contributions to society, and that they are very different from everybody else.

- Your own experiences of your own and other people’s ageing affect the ways you approach the topic of ageing and later life.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Rebecca Jones.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Moyan Brenn in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Reading 1: Laslett, P. (1989) 'Chapter 1: A New Division of the Life Course', A Fresh Map of Life: The Emergence of the Third Age. © Peter Laslett

MK to be OAP capital of the UK: Downes, S. (2013) 'MK to be OAP capital of the UK', Milton Keynes Citizen, 19 September 2013, © Johnston Publishing Ltd. [Online] http://www.miltonkeynes.co.uk/news/mk-to-be-oap-capital-of-the-uk-1-5504261 (Accessed 15 July 2014)

Reading 2: Katz, J., Holland, C., Peace, S. (2013) 'Hearing the voices of people with high support needs', Journal of Aging Studies, Vol. 27, Issue 1, pp. 52-60. © Elsevier. Used with permission.

Figure 2: © iStockphoto.com / evgenyatamaneko

Figure 3: © iStockphoto.com / diego_cervo

Figure 4: © Equality Authority. Used with permission.

Figure 5: © Jim Linwood. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Figure 6: © iStockphoto.com / Claudiad

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

© The Open University

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University