History of reading: An introduction to reading in the past

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 March 2026, 9:32 AM

History of reading: An introduction to reading in the past

Introduction

The 11 essays comprising this course cover a wide range of topics in the history of reading, each designed to whet your appetite to explore the subject further, by searching the UK Reading Experience Database RED yourself. We have designed this course for you to dip in and dip out of, allowing you to select the area that interests you most. Click on the links below to select the essays you’d like to read.

- Reading the English Bible

- Charles Dickens and his readers

- Jane Austen’s readers

- A famous novel and its readers: Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847)

- Childhood reading in the 1870s and 1880s: the recollections of Molly Hughes

- Reading and World War I

- Reading places

- Reading while travelling

- Samuel Pepys: diarist, book collector and reader

- Robert Louis Stevenson’s reading

- Reading culture in the Victorian underworld

Find out more about studying with The Open University by visiting our online prospectus

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

recognise an increased interest in exploring the history of reading

understand a range of examples of research into the history of reading

use RED to follow up any personal interests in the history of reading.

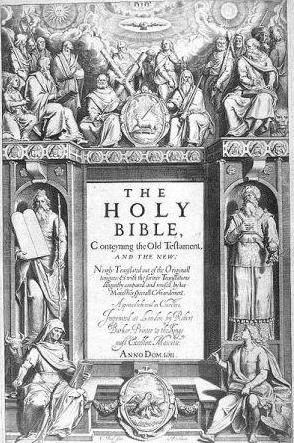

1 Reading the English Bible

By Bob Owens

The year 2011 marks the 400th anniversary of the publication of the most widely-read book in the English language: the translation of the Bible published in 1611 that has come to be known as the ‘Authorised Version’ or the ‘King James Bible’.

For more than 300 years this was the Bible people heard read in church every Sunday, and indeed it remained the best-selling Bible in the United States right up to the 1980s. It was not the first translation of the Bible into English. William Tyndale’s pioneering translation of the New Testament had appeared in 1526, but before he could complete the Old Testament he was hunted down and put to death as a heretic. In the sixteenth century, religious and secular authorities were very nervous about the idea that ordinary people should be allowed to read the Bible freely for themselves, and it was only in the Elizabethan age that Bible reading became at all widespread.

Vast numbers of copies of the authorised version of the Bible circulated from the seventeenth century onwards, in all kinds of formats – large and small, expensive and cheap. But how exactly did people read this most important of all books? And what impact did Bible reading have on them? There are many records in the UK RED site of Bible reading – nearly 1000 in total, and the number grows all the time. These enable us to explore the many different ways in which readers engaged with the Bible over the centuries.

Diaries are a prime source of evidence. In the diary kept by Puritan clergyman Isaac Archer from 1641 to 1700, he records that as an undergraduate at Cambridge he was ‘diligent in reading the scriptures every day’, and had read through the whole Bible each year for three years in succession, ‘according to Mr Byfield’s directions’ (UK RED: 22125).

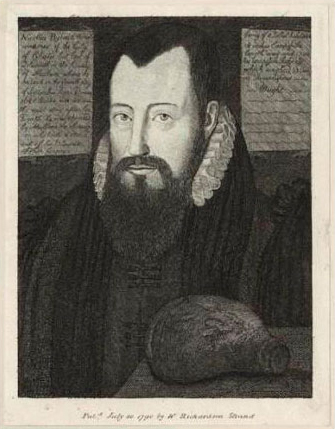

The ‘Mr Byfield’ here is Nicholas Byfield, author of Directions for the Private Reading of the Scriptures, first published in 1617, which included a calendar setting out which chapters are to be read each day, so that the entire Bible can be read from beginning to end over the course of one year. This piece of evidence shows how reading behaviour could be influenced by the advice given in books of instruction such as Byfield’s. Archer’s devotion to Bible reading was by no means unique. The diary of William Upcott, a bookseller’s assistant in the nineteenth century, reveals that he read about ten chapters of the Bible every morning and every evening (UK RED: 5917 and UK RED: 5918), and many similar examples can be found.

The most famous diarist on the UK RED site is Samuel Pepys. He is a wonderful source of evidence about reading, mainly because the information he gives is so precise. In his diary for Sunday 5 February 1660 (UK RED: 11620), to take just one example, he describes how, sitting beside his wife among the congregation in St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, London and feeling bored, he took up the Bible and ‘read over the whole book of the story of Tobit’. Pepys was evidently reading the text silently, but in public, among company. Although full of detail about the reader, the location, and the text being read this entry leaves many questions unanswered. Why did Pepys choose this particular part of the Bible? How exactly did he engage with the text: was he reading it purely for the story, or was he discovering deeper meanings in it? We can make some guesses in attempting to answer these questions. The Book of Tobit is included in the Apocrypha, the collection of books which up to the early nineteenth century was always included between the Old and New Testaments in the Authorized Version. It is an entertaining tale, with a fast-moving and eventful plot, and a cast of vividly drawn characters. It seems like just the thing to take Pepys’s mind off ‘a poor sermon’, and we might guess that he was reading Tobit more for literary pleasure than spiritual edification.

Bible reading was by no means only an activity for adults, and indeed in the past it was often the first book a child was given to read. In her Autobiography, written in 1855 and published in 1877, the feminist writer Harriet Martineau recalls her incessant early reading and study of the Bible (UK RED: 6622), describing how she made ‘Harmonies’ of the four gospels, and how much she was influenced by ‘the moral beauty and spiritual promises I found in the Sacred Writings’.

By contrast, it was the illustrations in the huge family Bible that sparked the imagination of the young Thomas Jackson: ‘There was one of Joshua’s army storming a hill fortress – with the great iron-studded door crashing down before the onrush of mighty men with huge-headed axes – that never failed to thrill’ (UK RED: 11442). What this entry reveals is how, even in a book as important as the Bible, features such as illustrations may be as important as the words themselves in determining the impact books make on readers.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

2 Charles Dickens and his readers

By Mary Hammond

Love him or hate him, it is widely accepted now that Charles Dickens was one of the giants of Victorian literature, far outselling his rivals and thus – so the story goes – exceptionally far-reaching in his power and influence. But how much influence did he really have, and on whom? Do healthy sales figures always equate to widespread enjoyment by readers? Evidence from the UK RED site gives us some diverse and often surprising answers.

Charles Dickens (1812-1870) about the age of 50, photographed by Mason & Co., c. 1862

Some entries support the common claim that working-class readers were particular fans of Dickens. East-Ender George Acorn was punished by his parents for wasting 3½d on a second-hand copy of David Copperfield, but later changed their minds by reading the saddest passages aloud to them (UK RED: 2368). Arthur Harding, a Victorian professional criminal, enjoyed A Tale of Two Cities and Dombey and Son when he read them in prison (UK RED: 5220), and another inmate, a fruit seller turned petty crook, was a Dickens expert who could perform any one of his characters on demand (UK RED: 12545). Similarly, while imprisoned in Reading Gaol in 1901, labourer Stuart Wood cried himself to sleep every night with ‘fellow sufferer’ David Copperfield in his arms (UK RED: 12644).

But the UK RED site also shows us that not all working-class readers felt the same about Dickens. One group of schoolboys being read A Christmas Carol by their teacher in the depressed steelworks town of Merthyr Tydfil between the two World Wars could not understand why Bob Cratchit was supposed to be hard done by when he had a perfectly good job (UK RED: 5222). And Norman Nicholson, son of a tailor, reading The Old Curiosity Shop and The Chimes in the 1920s, felt that ‘they were enough to sour a boy against the novels for the rest of his life’ (UK RED: 11378).

Women readers prove equally divided. Mary Russell Mitford, reading The Chimes in 1844, wrote to her friend Elizabeth Barratt Browning that she didn’t like it at all (UK RED: 17605), and received a letter in return in which Elizabeth claimed it had ‘touched me very much! I thought it and still think it, one of the most beautiful of [Dickens’s] works’ (UK RED: 17606).

Further, despite the common claim that he united Victorian families in the practice of shared reading, Dickens actually sometimes divided them. The mother of Thomas Jackson despised Dickens and suggested that her son read Thackeray as an antidote to the novels recommended by his Dickens-mad father (UK RED: 11444).

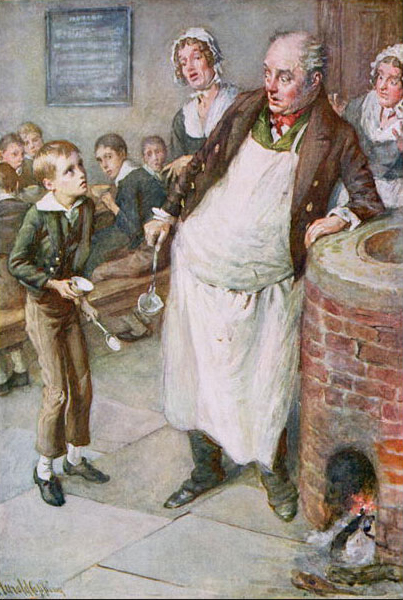

Children themselves had mixed opinions. The Victorian critic Andrew Lang recalled that as a child he used to be a swot, but being introduced to Dickens made him drop dull text-books for good (UK RED: 3213). Growing up in New Zealand in the late 1890s, Katherine Mansfield claimed with some pride that she could make the other girls cry when she read Dickens’s novels aloud in sewing class (UK RED: 3831). Several writers claim that it was reading Dickens as children that set them on their literary paths (UK RED: 3203; UK RED: 11249; UK RED: 17006), and his works had the still worthier effect of making the young R. L. Stevenson want to ‘go out and comfort someone’ (UK RED: 17574). But Vera Brittain was never able to read Dickens again after being read aloud to by her mother (UK RED: 20890), and when A. A. Milne, the future author of the Pooh stories, read Oliver Twist at the age of nine it gave him nightmares (UK RED: 3206).

Oliver asks for ‘more’, illustration for ‘Character sketches from Dickens’, compiled by B.W. Matz, 1924 (colour litho)

As well as recording disagreement among readers, entries in RED demonstrate the many different ways in which people read and the different needs reading can fulfill. In the 1850s novelist Elizabeth Gaskell read a bit of Little Dorrit over the shoulder of a fellow passenger on the bus and was frustrated that she had to get off before her companion turned the page (UK RED: 19152). In 1901 Newman Flower, later head of Cassell’s publishing house, rose at 4am to watch the funeral procession of Queen Victoria pass by and whiled away the hours of waiting by reading Bleak House, then got so engrossed in his book that he totally missed the cortege (UK RED: 3202). Victorian girls Mary Paley Marshall (UK RED: 4711) and H. M. Swanwick (UK RED: 4727) were both forbidden Dickens’s novels by their parents, but read them in secret anyway. Lady Charlotte Schreiber could only read him in small doses (UK RED: 7788), but Donald Hankey, an Army Subaltern, found that Dickens cheered him up no end when he was ill (UK RED: 10305). Virginia Woolf likewise found the ‘magnificent’ David Copperfield helped her headaches (UK RED: 7862), while her husband Leonard found Pickwick amusing while riding through the wilds of Ceylon (UK RED: 19790). Katherine Mansfield found reading Dickens in bed refreshed her after a hard day’s writing (UK RED: 3786).

Mr Pickwick addresses the club, illustration from The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (1812-1870), published 1837, litho, Hablot Knight Browne (1814-1892)

Some readers changed their minds about Dickens. The novelist Elizabeth Bowen ‘devoured’ Dickens as a child but found she could not read him as an adult (UK RED: 18770). Sir Walter Raleigh, Professor of English Literature at Oxford during the early part of the twentieth century, re-discovered Dickens years after he’d stopped teaching him and was caught up anew ‘in a flame of love and admiration’ (UK RED: 3229). But some were never admirers at all. For John Ruskin in 1874, American Notes was ‘dreadful beyond words’ (UK RED: 26067) and ten years later he still thought Dombey and Son ‘abominable’. Arnold Bennett, writing in the early twentieth century, agreed; ‘Nicholas Nickleby wasn’t so bad in its crude, posterish way’ (UK RED: 19221), he admitted, but The Old Curiosity Shop was ‘rotten vulgar, un-literary [and, biggest insult of all] . . . Worse than George Eliot’ (UK RED: 13036).

A best-seller Dickens certainly was, but the remarkable evidence in RED shows us the complexity and variety of his readers far beyond the story book sales can tell. And as a bonus, it reminds us how many habits and opinions we share with readers of the past.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

3 Jane Austen’s readers

By Katie Halsey

The first time I read Jane Austen’s Emma, I was fifteen. Bored one day during the Christmas holidays, when the weather was dreadful and the television worse, I turned to my mother’s bookshelf. Her cheap paperback edition of Emma, with its cover showing a dark-haired beauty in a Regency-style dress, caught my eye among the cookery and gardening books, and I picked it up, idly flicking through the pages.

Like many a reader before and since, in that moment I was caught in a golden snare from which there was no escaping. I read that book, cover to cover, in twenty-four hours. Lost in Austen’s fictional world, I hardly knew where I really was. Hartfield and Donwell Abbey seemed more real to me than my own home; Emma Woodhouse, Mr Knightley, Frank Churchill, Harriet Smith, Mr Woodhouse and the Eltons infinitely more interesting than my own family. I couldn’t put into words what it was about the writing that appealed to me so strongly but I knew, on putting Emma down, that I’d both encountered something entirely new to me and somehow found a friend who understood me, who spoke my language and thought my thoughts; someone who had, in some way I couldn’t understand, become a part of myself. That feeling - self-centred, even solipsistic, though it was - changed my life. I am now a lecturer in English literature, and my specialist subject is not hard to guess. Looking back on that moment now, it makes me wonder how many other people have felt that shock of recognition when reading Jane Austen, that sense that a kindred spirit speaks to them across a divide of time and space.

So I embarked upon a short voyage of exploration through the UK RED site, my aim being to discover what readers over the 200 years since Austen’s novels were first published have thought of the books and their author. I searched for ‘Jane Austen’ in the ‘Author of the Text being Read’ category, and discovered a large number of records which gave me a variety of responses. Many readers did comment on a feeling of ‘friendship’ with either Austen or her characters.

Anne Thackeray Ritchie, for example, described Jane Austen as the ‘unknown friend who has charmed us so long – charmed away dull hours, created neighbours and companions for us in lonely places’. Her characters are, to Ritchie, ‘familiar old friends’, and ‘like living people out of our own acquaintance’ (UK RED: 31360). Harriet Martineau similarly responded to Austen’s extraordinary gift of making her readers feel that they had ‘a score or two more of unrivalled intimate friends’ in her characters (UK RED: 9947).

Anne Thackeray Ritchie by Julia Margaret Cameron, albumen print, circa 1867

Princess Charlotte identified with Sense and Sensibility’s Marianne Dashwood, seeing in her ‘the same imprudence’ that characterised herself (UK RED: 146). Katherine Mansfield neatly described the peculiar quality of intimacy between Austen and her readers, encapsulating my own feeling by suggesting that ‘every admirer of the novels’ feels he or she has become the ‘secret friend’ of the author (UK RED: 31359).

The Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales, by George Dawe, 1817, oil on canvas

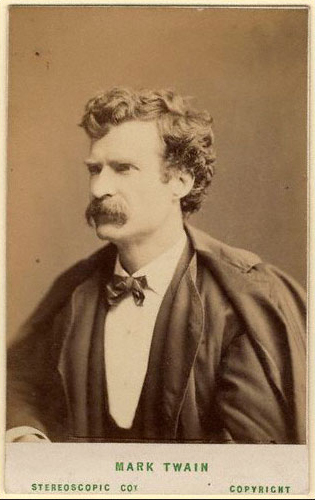

The American writer Mark Twain, on the other hand, was clearly very far from being an admirer of, or friend to, Austen’s novels. ‘Every time I read Pride and Prejudice’, Twain said, ‘I want to dig her up and hit her over the skull with her own shin-bone’ (UK RED: 8031).

Mark Twain, by London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company, albumen carte-de-visite, 1870s

Another writer, Charlotte Brontë, damned my favourite with faint praise: ‘I have likewise read one of Miss Austen’s works Emma – read it with interest and with just the degree of admiration which Miss Austen herself would have thought sensible or suitable – anything like warmth or enthusiasm ... is utterly out of place in commending these works’ (UK RED: 8029). At this point, I wondered which books did stir Charlotte Brontë to ‘warmth and enthusiasm’ – was there any way of finding out whether she had felt those moments of recognition and intimacy with a different kind of writer? A brief further search of RED ensued, this time for ‘Charlotte Brontë’ as a reader. I discovered, somewhat to my surprise, that Brontë rarely did express her views of books with much warmth. At least she hadn’t called Jane Austen ‘both turgid and feeble’, as she had a tale by Eliza Lynn Linton (UK RED: 4379), or, worse, ‘trebly wrong’, her impression of Thackeray’s lectures on Fielding (UK RED: 4412). She did describe the experience of reading Harriet Martineau’s Deerbrook (1839) as ‘a new and keen pleasure’ (UK RED: 9773), and George Sand’s Consuelo (1842-3) as ‘sagacious and profound’ (UK RED: 8028), but in general, Charlotte Brontë’s comments on Jane Austen show more, rather than less, ‘enthusiasm’ than those on other authors.

In my voyage through the UK RED site I have wandered a little distance from my original question (what readers have thought of Austen over 200 years). In doing so I have begun to unearth some valuable comparative material about the relationships between readers and their books more broadly, and to question my preconceptions and assumptions. Whether driven by personal interest or a particular research agenda, serendipitous discoveries, interesting connections, and unusual findings tend to make the researcher challenge more linear kinds of thinking about both history and literature. Perhaps, for all of us who use the RED site, new seas and uncharted waters lie ahead.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

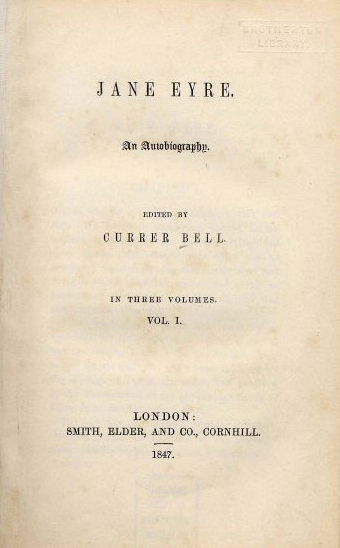

4 A famous novel and its readers: Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847)

By Rosalind Crone

‘Reader, I married him…’ These four words have become one of the most famous phrases in the English-speaking world, and many will be able to identify them as the opening to the final chapter of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Over the last 150 years, Jane Eyre has enjoyed a firm place in the English literary canon. Not only does it remain on the best-selling list, but in many schools children are required to read Jane Eyre as part of their literature studies. For those young readers, the description of the infamous Lowood School no doubt captures their attention; but for adults, its gothic overtones and poignant love story are truly evocative. Yet the publication of Jane Eyre was marked by controversy; not all readers foresaw that the novel would become one of the great classics of the nineteenth century.

The first edition title page of Jane Eyre

Although the first manuscript Charlotte Brontë sent to the publishers Smith, Elder & Co. was rejected, the encouraging comments from the editors convinced her to send in a second, ‘Jane Eyre: an Autobiography’, under the pseudonym ‘Currer Bell’. In his memoirs, George Smith, a partner in the firm, remembered receiving the manuscript:

The MS. of “Jane Eyre” was … brought it to me on a Saturday ... after breakfast on Sunday morning I took the MS. of “Jane Eyre” to my little study, and began to read it. The story quickly took me captive. Before twelve o’clock my horse came to the door, but I could not put the book down ... Presently the servant came to tell me that luncheon was ready; I asked him to bring me a sandwich and a glass of wine, and still went on with “Jane Eyre” ... before I went to bed that night I had finished reading the manuscript. (UK RED: 4370)

Portrait of Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855) by George Richmond (1809-1896) and engraved by Walker and Boutall

Needless to say, Jane Eyre was published, as a three-volume work on 19 October 1847, and quickly became a best-seller. Its rise to fame was, in part, driven by the tremendous curiosity it provoked among readers as to its authorship. Who was Currer Bell? And was Currer Bell in fact a woman? Lord Morpeth, for instance, wrote in his private papers, ‘very powerful & interesting, in parts very fine, not altogether pleasing — some striking delineation of character; it is said to be by a woman, but it is not feminine — I should certainly say by a Socinian — not by Miss Martineau’ (UK RED: 28531). And he was certainly right about that, as Harriett Martineau herself wrote to Fanny Wedgwood in February 1848, ‘Can you tell me about “Jane Eyre”, – who wrote it? I am told I wrote the 1st vol: and I don’t know how to disbelieve it myself, – though I am wholly ignorant of the authorship … it is surely a very able book (outside of what I could have done of it) and the way in which the heroine comes out without conceit or egotism is, to me, perfectly wonderful’ (UK RED: 9171).

Charlotte Brontë working on Jane Eyre (litho)

Great fame produced a demand for reviews. After receiving a copy of the book from the publisher, George Henry Lewes wrote to Elizabeth Gaskell that ‘the enthusiasm with which I read it made me go down to Mr Parker, and propose to write a review of it for Fraser’s Magazine’ (UK RED: 28478). But Lewes’s enthusiasm was not shared by all. Several reviewers condemned Jane Eyre, mainly because they saw in the character of Jane, and her relationship with Rochester, a challenge to societal norms regarding the place of women and morality. For instance, the critic for the Quarterly Review declared that the novel exhibited that ‘tone of mind and thought which has overthrown authority and violated every code human and divine’. It would only be natural that an author reading such reviews of their work would feel disheartened, and Charlotte Brontë wrote to her publisher on 17 November 1847, ‘The Spectator seemed to have found more harm than good in Jane Eyre, and I acknowledge that distressed me a little’ (UK RED: 28479). But for the most part, Brontë accepted the criticism in good humour, responding to critics’ comments on her identity with wit and strength: ‘The literary critic of [the Economist] praised the book if written by a man, and pronounced it “odious” if the work of a woman. To such critics I would say, “To you I am neither man nor woman – I come before you as an author only. It is the sole ground on which you have a right to judge me – the sole ground on which I accept your judgement’ (UK RED: 28652).

Controversy also emerged over the autobiographical content, promised on the title-page, and in part delivered as Brontë drew upon some of her own experiences to shape the story. As she wrote to the publisher in January 1848, ‘Jane Eyre has got down into Yorkshire; a copy has even penetrated into this neighbourhood: I saw an elderly clergyman reading it the other day, and had the satisfaction of hearing him exclaim “Why – they have got ––– school, and Mr ––– here, I declare! And Miss –––’ (UK RED: 4376). But if Brontë delighted in their recognition of the connections, it also sparked a long running dispute in the press as the son of Mr Carcus Wilson, founder of Cowan Bridge School, the inspiration for Lowood, desperately tried to clear his father’s name.

But despite these flash points in its reception history, for the majority of readers Jane Eyre provoked pleasure, not outrage, and it inspired Brontë’s literary peers to speak of her in the same breath as Austen, Edgeworth, Trollope and Dickens. And its appeal has proved timeless. Just as the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray declared in 1847 that the book ‘made me cry, to the astonishment of John who came in with the coals’ (UK RED: 4371), so Hilary Spalding, a young girl, wrote in her diary in 1927, ‘am reading Jane Eyre, and adore it’ (UK RED: 6644).

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

5 Childhood reading in the 1870s and 1880s: the recollections of Molly Hughes

By Alexis Weedon

The three volumes of autobiography published by the educationalist M.V. (Molly) Hughes (1866–1956) are a rich source of information on the books she read and loved as a child. Originally published as A London Child of the Seventies (1934), A London Girl of the Eighties (1936), and A London Home of the Nineties (1937), they were republished in 1991 as a single-volume trilogy, A London Family, 1870–1900. The childhood books read by Hughes fall broadly into three categories: school or educational books, children’s fiction and Sunday reading. Her commentary on them captures the appeal of these books for the child reader, and her autobiography is a good indicator of the attraction these books held for children of her class and generation. The inclusion of more than forty of her documented reading experiences in the UK RED site allows us to search them in many different ways.

Molly Hughes

Up to the age of eleven, Molly was taught at home. She recalled how, every day her ‘mother would summon me to her side and open an enormous Bible. It was invariably at the Old Testament, and I had to read aloud the strange doings of the Patriarchs’ (UK RED: 410). The size of many of her early books remained in her memory, as if it were associated with the difficulties of learning. By contrast with the ‘enormous Bible’, for instance, her English history came from ‘a small book in small print that dealt with the characters of the kings at some length’ (UK RED: 412). Illustrated texts enchanted her. So, for example, she says that ‘it was entirely due to its colour that another book became my constant companion… an illustrated Scripture text-book, given to me on my seventh birthday, and still preserved’ (UK RED: 552). Another ‘prime favourite’ among her early books was P.J. Stahl’s Little Rosy’s Voyage Round the World (1869), in which each adventure was accompanied by a full page illustration by Lorenz Frolich. But narratives were important too: ‘Not as a lesson, but for sheer pleasure, did I browse in A Child’s History of Rome, a book full of good stories’ (UK RED: 414).

At the age of twelve she went to school, where she remembered being ‘placed in the lowest class with three other little girls of my own age, who were reading aloud the story of Richard Arkwright [the famous inventor of the water-powered spinning frame]’ (UK RED: 557). Among her set school texts was one of the most successful history books of her day, written by Maria Graham (later Lady Callcott): Little Arthur’s History of England, originally published in 1835. To Molly, it could be ‘read like a delightful story’ (UK RED: 558). She learned English grammar by parsing The Tempest, and remembered spending a whole term on the first two scenes (UK RED: 559).

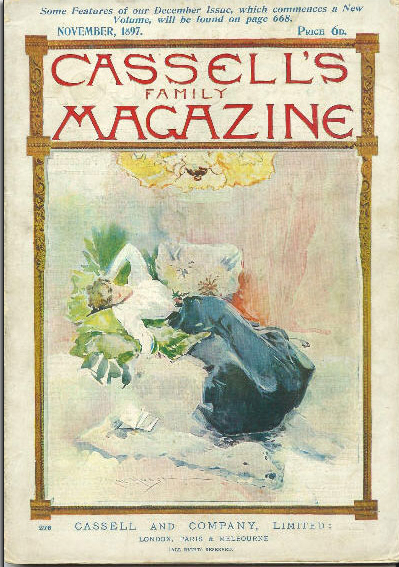

It is evident that Molly and her four elder brothers shared their books, passing their enthusiasm to one another. She describes borrowing from her brother a lavishly illustrated book entitled The Story Without an End (1872), which had been given to him as a birthday present: ‘The story itself was an allegory, and was too subtle for us, but it is impossible to describe the endless pleasure given us by those full-page pictures’ (UK RED: 551). They were equally keen on R.M. Ballantyne’s The Iron Horse (1871) which was the first book they bought together with their own pocket money: ‘Surely no book was ever read and re-read and talked over as that first new volume, although we went on to buy many more’ (UK RED: 916). They also shared their magazines with each other, and indeed the whole the family read Cassell’s Family Magazine: ‘I think every word of it found some reader in the family’, Molly recalled (UK RED: 918).

Cassell’s Family Magazine, November 1897

Sunday reading was a class of its own and Molly vividly recalled what she was allowed to read on that day. Her treasured Sunday books were typical examples of the genre. For instance, F.L. Bevan’s The Peep of Day was a popular gift book of the time. It retold stories from the Bible, explicating their morals and reinforcing them by a collection of verses at the back. Molly thought that, like many others, she had ‘imbibed [her] early religious notions’ from this book (UK RED: 554). By contrast, she found little entertainment in a Sunday book she was given by a particularly religious aunt, The Narrow Way, being a Complete Manual of Devotion for the Young (1868), declaring that ‘no one could really be as good as this book wanted and that it was a fearful waste of time’ (UK RED: 913).

There are other examples of what we might call ‘resistant’ reading, or ‘reading against the grain’. A particularly improving tale given to Molly by her mother was Mary Butt’s The History of Henry Milner (1823–37), a three-volume account of the upbringing of a perfect Christian gentleman. Molly and her brothers, however, only liked ‘certain parts’ of the story: ‘I believe he [the hero Milner] never did anything wrong, but his school-fellows did, and all their gay activities shone like misdeeds in a pious world’ (UK RED: 886). Her attitude to such reading shows how attempts to inculcate conventional standards of respectability could be undermined by resistant reading practices. It is also clear that as a child reader Molly could find amusement in the stories and illustrations of the driest of books.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

6 Reading and World War I

By Edmund King

World War I could easily be described as ‘the first great war of words’. When primary schooling was made compulsory in Britain in 1880, the literacy of the general population increased markedly. Those born in the years after the Education Act of 1880 were the first generation of British children who all received at least a basic education. They were also, of course, those who would grow up to experience the events of 1914-1918. Due in large part to the relatively new phenomenon of mass literacy, the First World War was a highly textual conflict.

Magazines and daily newspapers carried war news to huge audiences, and were eagerly sought by British readers overseas. After a long and dangerous trek through Serbia in 1915, English nurse Dorothy Newhall recorded the thrill of finding ‘an English newspaper’ in her Italian hotel, the first she had seen ‘in a long time’ (UK RED: 30996). Late in 1914, English schoolteacher Kenneth Bickersteth wrote to his family from Australia, noting how ‘eagerly read’ the newspapers were in Melbourne because of the war. He also described the crowds of people that would gather outside the offices of the Melbourne Argus, waiting to read the latest overseas ‘cablegrams which are … put up for passers-by to see’ (UK RED: 30895).

Australian soldiers resting on their way to the front, September 1917

For those whom the war took overseas, keeping close ties with home was a crucial part of maintaining morale – and sanity. The most convenient way of doing this was through the exchange of letters and parcels. By 1917, the British Army was sending almost 9 million letters a week from the Front, and the numbers coming the other way were, if anything, larger. In addition to letters from home, many servicemen and women were also sent books, newspapers, and magazines. The young Henry Williamson, who would later pen the children’s classic Tarka the Otter, wrote from the Front in March 1917 asking his parents not to ‘forget a cake & send Daily Mail every other day and Motor Cycle & Motor Cycling and the mags’ (UK RED: 30094).

Aside from being a way of maintaining bonds with family, the written word provided another vital component in a soldier’s mental armoury – a means of distraction. The anxiety produced by obsessing about the dangers and uncertainties of war could lead not only to psychological but also physical breakdown. Being able to read while on active service provided a valuable means of escape – a way of separating oneself mentally for the duration of the reading experience from one’s surroundings. Serving in Palestine in early 1918, ambulance man Vero Garratt found that reading could provide him with two things that military life often prevented him from enjoying – solitude and privacy. ‘When evening came,’ he wrote, ‘I sought the isolation of a disused hut … and revelled in poetic creations by candlelight as a solace to my distraught mind. And as the Palgrave’s Treasury [a popular anthology of poetry] became more battered so it became more of a blessing’ (UK RED: 31106).

Sometimes, however, an attempt to escape from the trials of military life through books could inadvertently bring a reader jolting back into the moment. Edwin Campion Vaughan, a young officer in the battle of Third Ypres, turned to his copy of Palgrave’s anthology to get him off to sleep one night, after the evening’s shell-fire had died down. However, this did not go quite according to plan:

I took my Palgrave from the valise head; it opened at ‘Barbara’ and I read quite coldly and critically until I came to the lines

In vain, in vain, in vain

You will never come again.

There droops upon the dreary hills a mournful fringe

of rain

then with a great gulp I knocked my candle out and buried my face in the valise. (UK RED: 29117)

Some of the most engaged and insistent readers in World War I were civilian internees and prisoners of war. The monotony of prison life often led to anxiety and depression, as prisoners were left with nothing to do but obsess about their own futures and the outcome of a war they could no longer directly influence. The frequent mentions of reading in prison diaries and memoirs reveal how effective books could be in providing temporary respite from these states of mind. Gerald Featherstone Knight described life in an officers’ POW camp as ‘one long queue,’ and described how the prisoners

passed the morning waiting … for … newly arrived parcels, while soon after lunch it was customary to see the more patient individuals already lining up chairs and settling down to their books, to wait for hot water which was sold at tea time. (UK RED: 31060)

Due largely to demands from prisoners themselves, the Red Cross and YMCA were instrumental in supplying books to POWs, many of whom organised their own prison-camp lending libraries.

In a book written more than thirty years ago, one of the major historians of World War I, John Ellis, dismissed reading as ‘a not very popular occupation’ with soldiers. The soldier ‘who wanted something to read was the exception,’ he argued, and the efforts of government and voluntary organisations to supply reading materials for soldiers had ‘very little effect’. As the examples quoted here show, and there are many more like them in the UK RED database, Ellis’s statement is simply wrong.

Letters and newspapers from home played a vital part in maintaining morale in the British and Commonwealth armies, and many soldiers recorded how books allowed them to escape the boredom and discomfort of active service. On the civilian front, meanwhile, British readers possessed an almost insatiable appetite for war news, and newspapers and magazines were widely read. Written culture was vital to the experience of World War I. Reading allowed people not only to keep in touch with current events, but to keep in touch with each other. For soldiers and relief workers in the field, meanwhile, having access to books allowed them to maintain their own sense of identity and connection with wider culture, during a time when these ties seemed otherwise fragile and under threat.

A Scottish soldier reading a letter while on gas sentry duty near the trenches

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

7 Reading places

By Stephen Colclough

The places in which readers engaged with texts are of particular importance to anyone interested in the history of reading, because readers don’t just engage with the object being read, they also take note of the context in which it is encountered. Indeed, the sights, sounds and even the smells of the places in which texts are read may have a profound effect upon how readers make sense of them. The UK RED site contains a great deal of information about where reading experiences took place. The period 1750-1850, with which this short introduction to investigating reading places is concerned, saw a great expansion in the number of venues for reading – from the increasing number of homes that included a room called ‘the library’, through to the opening of the first ‘free’ public libraries, which often included ‘reading rooms’.

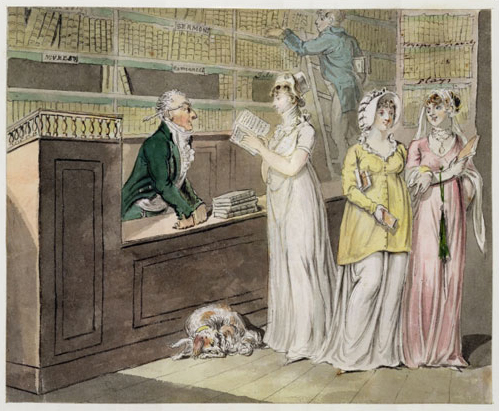

Subscription libraries and book clubs, which usually charged members for access, became increasingly popular with middle-class readers during the late eighteenth century. Book clubs often met at members’ houses or in local inns and the opportunity to be sociable was one of their key attractions. Entries in RED for the Rev Benjamin Newton show that his membership of the Bedale Book Club often involved him in lively ‘disputes’ after dinner, such as that over the ‘spelling of experience’ which took recourse to the Bible to resolve (UK RED: 5339). Access to clubs and subscription libraries was usually restricted by social class, but perhaps the most famous reading space of the period – the commercial circulating library – was open to anyone who could afford to join. Some even rented out books by the volume at a penny or two per night. The ‘juvenile offender’ J. L., for example, borrowed novels about highwaymen at 2d per volume in the 1830s (UK RED: 1576). Many of the most famous commercial circulating libraries were part of the tourist industry. Located at seaside resorts or in spa towns – like Bath – they catered for people who wanted to read while on holiday. Some were exceedingly handsome and functioned as places to see as well as in which to be seen.

The Circulating Library, Isaac Cruikshank (1764-c.1811), pen and ink and water colour and wash on wove paper

Books and newspapers could usually be consulted in the library, but most readers returned to their lodgings to read. Texts were often shared, as occurred when Frances Burney and friends returned from a library in Bath with a copy of Hannah Cowley’s The Maid of Aragon, and Hester Thrale made the discovery that it was dedicated to her father while reading aloud to the group (UK RED: 8596).

Contemporary images often paint a negative picture of such venues as serving mainly female novel readers. However, the kind of evidence being recorded in RED reveals a more complex picture of actual use. Young male readers are not part of the stereotypical picture of a circulating library, but the thirteen year-old Joseph Hunter used Lindley’s Circulating Library in Sheffield to acquire texts including a volume of ‘one of the Prettyest [sic] novels I have ever read’ that had been lost at the subscription library to which he belonged (UK RED: 10800). The RED entries for Hunter reveal a reader who was able to move quite casually between the many commercial and non-commercial reading spaces offered by his home town.

By 1750, London coffeehouses were long established reading spaces, but they only really become a feature of working-class life in the early 19th century. The working-class autodidact Thomas Carter was an early enthusiast, noting in his autobiography that during 1815 he frequently read the previous day’s newspapers while eating breakfast in a coffee shop on his way to work. This resulted in his workmates adopting him as their ‘news purveyor’ and he often kept them abreast of ‘public affairs’ (UK RED: 7621). The Victorian journalist Angus Reach noted that the newspapers and novels provided in such coffeehouses were often covered with the traces of previous sticky-fingered readers and it is worth considering for a moment how often the communally consumed text must have taken on the flavour of its surroundings. The novelist Charlotte M Yonge recalled that her family were opposed to circulating libraries because the books were ‘very dirty, very smoky, and with remarks plentifully pencilled on the margins’. The Yonges chose instead to become members of a local book club and Charlotte notes how enjoyable it was to hear her parents reading the books borrowed to the ‘assembled family’ in the early evening.

There is much evidence to suggest that organised family readings of this sort occurred fairly frequently in middle-class homes during the 19th century and the bourgeois house is clearly one of the most important reading venues of the period. RED is a brilliant resource for finding readers all over the house, from servants reading by the fire in the kitchen (UK RED: 5831) to curling up with a novel in the bedroom (UK RED: 426), though there are, as yet, no entries for reading in the ‘smallest room’ in this period. As these examples show, the remarkable evidence being added to RED provides an invaluable resource for anyone who wants to know not only where texts were read in the past, but how these locations impacted upon reading practice.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

Hall’s Library at Margate, 1789 (coloured engraving), Thomas Malton (1748-1804)

8 Reading while travelling

By Simon Eliot

Until recently – certainly until the laptop, mobile phone, and personal stereo took over – travel, and particularly the daily commute, was characterised in buses and trains by people intent on a newspaper, a magazine or a book. We nowadays travel much more frequently, more cheaply, much further, and much faster than our forebears did, though whether to much more purpose and effect is debatable. The coming of the railways, the internal combustion engine, and powered flight transformed and multiplied enforced reading opportunities but, even before these, reading and travel were closely associated.

Riding a horse, unless at a canter or a gallop, could be done with one hand, thus releasing the other to hold a book or a paper. Here is Samuel Pepys riding to Chatham on 3 August 1665 and using reading to flatter an attractive woman:

And so we set out for Chatham – in my way overtaking some company, wherein was a lady, very pretty, riding single, her husband in company with her. We fell into talk, and I read a copy of verses which her husband showed me, and he discommended but the lady commended; and I read them so as to make the husband turn to commend them. (UK RED: 12240)

More commonly Pepys would use a carriage and, when the woman was not sufficiently attractive, found reading more so. In his diary for 26 October 1664 he records that as he was getting into his carriage that day, ‘an ordinary woman prayed me to give her room to London; which I did, but spoke not to her all the way, but read as long as I could see my book again’ (UK RED: 12140).

Light in the past was always a problem, at home and on the road – and on railways. It was particularly difficult in the blackout in late 1939:

Oh, I have strained my eyes trying to read, and had to give it up in the end. I call it dismal, sitting for half an hour or more in a dark, gloomy carriage, so’s you can’t read; can’t even look at the girls sitting opposite you; can’t see your station. (UK RED: 10144)

Motion sickness can always be a problem for a reader on the move. On 3 December 1832 Fanny Kemble was travelling by coach from Amboy to Delaware in the USA but, to her exasperation, ‘The roads were unspeakable’. She ‘attempted to read, but found it utterly impossible to do so’ (UK RED: 7864).

There were strategies that might help in such circumstances. Hester Thrale observed that:

Apropos to riding in a coach, Perkins told me that he had found out the Secret how to read in a Carriage and would tell it to me, to whom it might be useful; he put a Piece of Paper he said on the Page he was reading, & so moved it when he came to the End of the Line. (UK RED: 23269)

However, there were occasions when, for a less pious person than Elizabeth Fry, an excuse not to read might have come in handy:

We have two Scripture readings daily in the carriage, and much instructive conversation; also abundant time for that which is so important, the private reading of the Holy Scripture. This is very precious to dear Elizabeth Fry, and I have often thought it a privilege to note her reverent ‘marking and learning’ of these sacred truths of divine inspiration. (UK RED: 23124)

Travelling took much time, and books were rather expensive, so careful organisation was necessary to maximise the benefit, as John Marsh recorded on 9 April 1796:

On the next day I went to Canterbury in the diligence [i.e. stage-coach], during w’ch I amused myself with reading part of Voltaire’s ‘Candide’, w’ch having read a great many years ago at Salisbury & almost forgot, I bought the day before in duodecimo. Having dined at the King’s Head I went out & got ‘Caleb Williams’ of w’ch I had heard much & of w’ch I read great part of the 1st vol. in the evening at the King’s Head (where I also supp’d & slept) leaving the 2d. vol of ‘Candide’ to read on my return to London. (UK RED: 7932)

However, travelling also gave opportunities for serendipity, a chance multiplied by the number of stops a mail coach, for instance, had to make (on average once every twelve miles) to replace the horses. On 6 August 1825 Anne Lister

Found on the table at the inn (in no.9, a very nice small parlour with a lodging opening into it), among several other books, Rhodes Peak Scenery, in 4, I think, thin 4to vols, with plates. Read there the account of Bakewell Church, Haddon Hall etc. (UK RED: 3019)

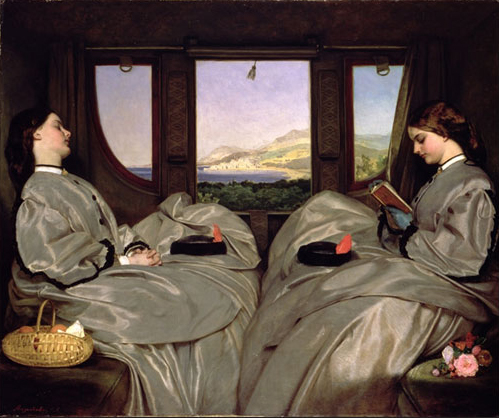

The Travelling Companions by Augustus Egg

In the railway age bookstalls – many run by W.H. Smiths – could provide the same possibility of a surprise discovery. In the late 1850s Jessie Boucherett

caught sight, on a railway bookstall, of a number of the Englishwoman’s Journal. She bought it, attracted by the title, but expecting nothing better than the inanities usually considered fit for women. To her surprise and joy she found her own unspoken aspirations [regarding women’s employment] reflected in its pages. (UK RED: 4852)

I shall end with a piece of serendipity made possible by the RED site itself. Searching for ‘reading’ and ‘rail’ I came across the following from Charlotte Brontë written in the earlier part of 1845 which, although it has nothing to do with reading while travelling, reveals the author of Wuthering Heights as a down-to-earth and successful investor in railway shares:

There is nothing so uncertain as rail-roads; the price of shares varies continually – and any day a small share-holder may find his funds shrunk to their original dimensions. Emily has made herself mistress of the necessary degree of knowledge for conducting the matter, by dint of carefully reading every paragraph and every advertisement in the news papers that related to rail-roads and as we have abstained from all gambling, all mere speculative buying- in and selling-out – we have got on very decently. (UK RED: 28466)

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

9 Samuel Pepys: diarist, book collector and reader

By Rosalind Crone

In his diary for 10 January 1662, Samuel Pepys wrote: ‘I late reading in my Chamber; and then to bed, my wife being angry that I keep the house up so late’. In many respects this is a mundane entry, and similar to a large number of the reading experiences that he recorded. Yet it is capable of arousing a strong sense of empathy among equally habitual readers. Pepys was in many respects an ordinary reader. Born in London in 1633 and educated at Cambridge, he was a middling professional who worked in the civil service, predominantly for the Admiralty, and lived in the heart of the City. He became famous as a result of his substantial and unique book collection, bequeathed to Magdalene College, Cambridge, but most of all through his diary which he kept meticulously for the decade of the 1660s, presenting a colourful account of events and life in the decade of Restoration, while providing an almost unrivalled insight into the tastes and habits of a 17th century reader.

Samuel Pepys by John Hayls, 1666

The UK RED site contains more than 500 entries of reading experiences collected from Pepys’s diaries, the vast majority of which (more than 400) are records of Pepys’s own interactions with the written word. He was, in many respects, a curious intellectual, with obvious tastes in history and science. Thomas Fuller, author of The Church History of Britain (1655) and History of the Worthies of England (1662), and Robert Boyle, author of (among others) Experiments and Considerations Touching Colours (1664) and Hydrostatical Paradoxes (1666) ranked as two of his favourite contemporary authors, and he read these books several times over the course of the decade. Pepys was, then, an intensive reader, seeking to engage with the text and exploit books to their full potential. As he wrote on the evening of 28 April 1667, ‘mightily pleased with my reading Boyles book of Colours today; only, troubled that some part of it, indeed the greatest part, I am not able to understand for want of study’ (UK RED: 14405).

But he was also an extensive reader, his encounters with text covering the full spectrum of genres and forms of print available in the seventeenth century. Pepys delighted in reading plays, both to himself, and in the company of friends and family. ‘And so by coach home’ he wrote on 20 October 1668, ‘and there, having this day bought the “Queene of Arragon” play, I did get my wife and W. Batelier to read it over this night by 11 a-clock, and so to bed’ (UK RED: 14951). Popular ballads similarly amused Pepys. When presented with some at a funeral in May 1668, ‘I read and the rest came about me to hear; and there very merry we were all, they being new ballets [ballads]’ (UK RED: 14901). Later, he specially bound together a collection of these ballad sheets to be included in his library. However, Pepys did not intend to make all of his reading public. His diary reveals a habit of burning books which he had read, but did not want to be part of his famous library. For instance, on 9 February 1668, after saying farewell to friends, Pepys retreated to his chamber, ‘where I did read through “L’escholle des Filles”; a lewd book … and after I had done it, I burned it, that it might not be among my books to my shame’ (UK RED: 14891).

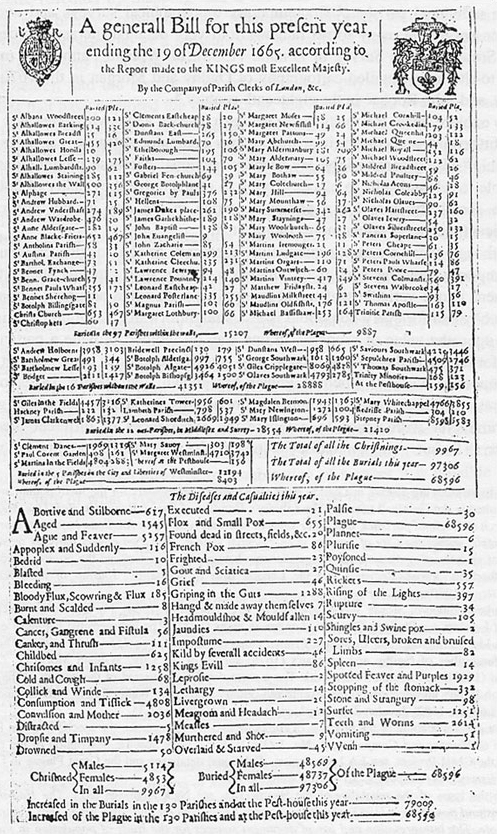

As Pepys was such an avid reader, books and texts featured in his descriptions of some of the key events of the 1660s. During the period of the Great Plague in 1665, he makes reference to reading the mortality bills pasted on public walls to inform the people of the fatality rates. At the height of the disaster in September 1665, Pepys recorded the following in his diary, ‘Here I saw this week’s Bill of Mortality, wherein, blessed be God, there is above 1800 decrease, being the first considerable decrease we have had’ (UK RED: 12247).

Bill of Mortality from The Great Plague, 1665

Books also featured predominantly in Pepys’s descriptions of the Great Fire of London in September 1666. Fearing their house may be in danger, Pepys dispatched their most valuable possessions to the country, including his books. In the aftermath, Pepys records the trouble he was put to in unpacking his collection, but more importantly, makes reference to the great damage done to the bookselling trade located in St Paul’s Churchyard. Almost a year later, he purchased and read with great pleasure William Dugdale’s Origines Juridiciales (1666), a history of English laws and law courts, ‘of which there was but a few saved out of the Fire’ (UK RED: 14399).

Even if a great many of the references to his everyday reading appear, at first glance, repetitive, when examined more closely it is clear that there is nothing dull about Samuel Pepys’ reading experiences. The entries in the UK RED site capture the great diversity and fine texture of Pepys’s relationship with the written word, and in particular, the way in which reading was incorporated into every aspect of his life. For Pepys, reading had a variety of uses, and could be a source of both pleasure and pain. Most of all, Pepys’s diary reminds us that the reading experience is never ‘ordinary’.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

10 Robert Louis Stevenson’s reading

By Shafquat Towheed

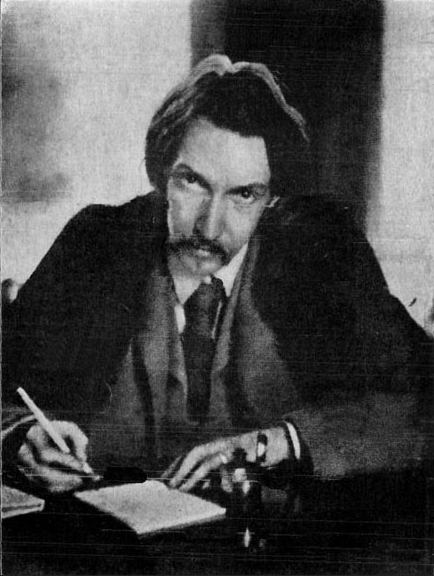

The author of bestsellers such as Treasure Island (1883) and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1885), Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894) was one of the greatest literary celebrities of his age, and together with Sir Walter Scott, he is considered to be Scotland’s greatest nineteenth-century writer. Stevenson was a prodigious talent, writing in many different genres: poetry, travel writing, the novel, short fiction, drama, journalism and the literary essay. As well as being a highly prolific writer, Stevenson was from his early childhood, an avid and voracious reader. We can piece together a great deal of information about Stevenson’s reading from the records that he has left behind, especially the references to his reading in his correspondence.

Robert Louis Stevenson at his desk

So what did Stevenson read? Using the ‘advanced search’ facility of the UK RED site, we can delve into the records and find out what books Stevenson read during a specific time in his life, before he became a famous author: his childhood and young adulthood while living in his parental home in Edinburgh, 17 Heriot Row. There are more than 50 records, and we can learn a lot about Stevenson’s reading by studying them. One thing they reveal is that Stevenson read many books that were not in English or about Britain. He read several major works in French, including novels such as Gustave Flaubert’s Le Tentation de Saint Antoine, which he read twice and declared to be ‘splendid’ (UK RED: 17758), Théophile Gautier’s Le Capitaine Fracasse - read in the evening in front of the dining room fire (UK RED: 17784) - and Alexandre Dumas’ Le Vicomte de Bragelonne (UK RED: 13546). He also read non-fictional French prose such as Michel de Montaigne’s Essais, which he considered to be ‘light reading’ (UK RED: 17778) and poems by Charles Baudelaire - ‘some of these are really very excellent’ (UK RED: 18015) - and Réné-François Armand Sully-Prudhomme, whose work he considered ‘adorable’ (UK RED: 18160).

Stevenson read French fluently from childhood, and his writing was heavily influenced by French writers of adventure and romance, such as Alexandre Dumas; he drew upon both The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers in his own writing. Stevenson was also a competent reader of German, evidenced by his reading and response to Heinrich Heine’s poems in Buch der Lieder; Stevenson learned some of these poems off by heart (UK RED: 17280), or copied them out in his letters (UK RED: 17771). He also read a lot of British writers, such as George Eliot (UK RED: 16110), Benjamin Disraeli (UK RED: 13545), and Harrison Ainsworth (UK RED: 13550), and American writers, like Walt Whitman (read late at night, UK RED: 17720) and Edgar Allen Poe (a reading experience which stopped him from sleeping, UK RED: 18073). Stevenson’s reading covers many different genres, from science (Darwin, Spencer) to religion (The Bible, John Knox, Foxe’s Book or Martyrs), and from history (Macaulay, Hallam) to books on civil law. While living in the parental home in Edinburgh, Stevenson’s reading shows his interest in the wider world beyond Europe, seen in books on America and Japan.

Stevenson read widely, but he has also been widely read. Because of the popularity of Stevenson’s books, there are also a good number of entries of readers of his works in the RED database, often with divergent views. King Kalakaua of Hawai’i was an avid fan (UK RED: 3900), while the British Orientalist Gertrude Bell preferred reading Stevenson’s essays to visiting the Eiffel Tower (UK RED: 30778). Treasure Island was one of the first books the novelist Rose Macaulay read as a child (UK RED: 2728), while for the poet laureate John Masefield, Stevenson’s adventure novel of pirates on the high seas was a formative teenage influence, first read on board ship (UK RED: 5758). For Arthur Vanson, a British child growing up in Paris, the influence of Treasure Island was so great that he renamed parts of the Bois de Boulogne after the book (UK RED: 13996). Not all readers loved Stevenson, however. The Bloomsbury novelist E.M. Forster thought Treasure Island insincere (UK RED: 20743) while the 16-year-old Hilary Spalding (reading Kidnapped during World War II) felt that it was ‘not up to much’ (UK RED: 6641). For members of the XII Book Club, an English Quaker reading group active during World War I, the charm of reading Stevenson was that each reader had their own favourite work, as noted in their minutes:

It is difficult for anyone to sum up the results of the discussion - it was soon apparent that to some members his essays were the one & only thing worth having, to others his stories, Treasure Island, Island Nights Entertainments & so on reveal his greatness: to others, his letters are the thing & so one might proceed (UK RED: 27224).

Readers through history have evidently had their own favourite Stevenson works, treasured above the rest of his writing. What are yours?

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

11 Reading Culture in the Victorian Underworld

By Rosalind Crone

For some years now, we have been treated to many colourful accounts of the Victorian underworld. Documentaries, serialisations of the 19th century classics, neo-Victorian novels and sensational books have evoked the smells and sounds of the slums while exposing the lives of thieves, beggars, scavengers, casual labourers and market sellers. From these accounts, we know a great deal about their dark culture, including the ‘flash’ language which many used to subvert authority. But where did books fit in to all of this? The 19th century was an age of abundant cheap print. Did the slum dwellers take advantage of this? Could these men, women and children even read at all?

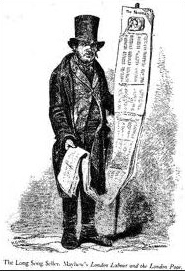

This question also intrigued the middle and upper classes of the mid-nineteenth century. Concern about poverty and rising crime rates encouraged a substantial number of men to explore the underworld and they completed detailed studies, often with some statistical basis, on the lives of those who lived below the bread line. Perhaps the most famous of these was Henry Mayhew’s ‘London Labour and the London Poor’, first serialised in the established newspaper, The Morning Chronicle, in 1849–1850 and later published as a four volume set in 1861–1862. Although rarely acknowledged today, this study helped to unearth a vibrant reading culture among those struggling to survive.

Even Mayhew was surprised to find that such a large number of slum dwellers could read. The two orphan flower girls he found in Drury Lane ‘insisted upon proving to me their proficiency in reading, and having procured a Roman Catholic book, the “Garden of Heaven”, they read very well’ (UK RED: 1260). It is true that this evidence is illustrative of the great increase in literacy over the course of the Victorian period. But it is worth mentioning that few of those interviewed by Mayhew had taken advantage of the new charitable educational institutions often championed for eliminating ‘ignorance’. Mayhew’s interviews revealed that many costermonger children were taught to read by their parents or siblings. A coster-girl aged 18 explained to Mayhew that her mother had taught the elder children to read: ‘She always liked to hear us read to her whilst she was washing or such like! and then we big ones had to learn the little ones’ (UK RED: 30408).

Some even taught themselves. A ‘cheap John’ selling printed songs wished to be able to read them, ‘and’, he explained, ‘with the assistance of an old soldier, I soon acquired sufficient knowledge to make out the names of each song, and shortly afterwards I could study a song and learn with words without anyone helping me’ (UK RED: 1265). Crucially, while many of these men, women and children could read, they had not acquired the skill of writing.

A long song seller (printed song seller) from Henry Mayhew’s, London Labour and the London Poor (London, 1861)

Literary culture in the Victorian underworld was inclusive: there was no simple dividing line between those who were literate and those who were not. All found a way to enjoy the range of cheap literature appearing at their fingertips. Sellers of ballads and broadsheets sung or shouted the contents of their wares to customers. These sheets also contained verses that could be learned by heart and pictures to gaze upon for those unable to read their short texts. Moreover, families, friends and neighbours often clubbed together to purchase sheets, periodicals and newspapers – literates and illiterates were not strangers; at least one member of the group would be able to read to the others. It could be a frustrating experience, as a regular scavenger told Mayhew: ‘I likes to hear the paper read well enough, if I’s resting; but old Bill, as often volunteers to read, has to spell the hard words, so that one can’t tell what the devil he’s reading about’ (UK RED: 1271). But more often than not, group reading was pleasurable, and of great community importance. Mayhew discovered a group of costermongers who gathered in the courts and alleys where they lived to hear the ‘schollard’ read the latest penny fiction, or ‘penny bloods’, aloud to them (UK RED: 1257). The costermongers were not a passive audience: all frequently interrupted the readings, asking for further explanations and giving their opinions. ‘Anything about the police sets them talking at once’, explained the ‘schollard’. A description of a fierce fight interrupted by policemen with truncheons provoked this exchange:

‘The blessed crushers is everywhere’, shouted one. ‘I wish I’d been there to have had a shy at the eslops’, said another. And then a man sung out: ‘O, don’t I like the Bobbys?’

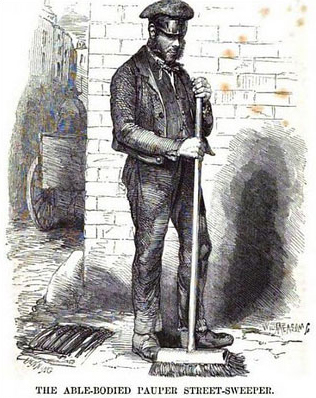

But it would be wrong to assume that the tastes of the poor were confined to cheap trash, full of sensation, violence and crime, and providing inducements to criminal or otherwise unacceptable behaviour. Perhaps surprisingly, literary culture in the slums included works that we would regard as high-brow or canonical, works that a reader would need some skill and intellect to decipher and enjoy. Yet the crossing sweeper who was reading the infamous Reynolds’s Miscellany the night before his interview had also read The Pilgrim’s Progress three times over! (UK RED: 1273) The crippled penny mousetrap maker, ‘for an hour’s light reading’, turned to Milton’s Paradise Lost and Shakespeare’s plays. [1282] And a sweet-stuff maker bought unwanted printed paper to wrap his wares from the stationers or at the old bookshops – as he read the text before he used the paper, ‘in this way he had read through two Histories of England’. [1261]

An ‘able-bodied pauper street-sweeper’ from Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (London, 1861)

This represents just a small taste of the sheer variety in reading tastes and practices that Mayhew, and other social explorers, uncovered in the underworld of the Victorian age. Contributors to the RED site have joined these together with other records, from nineteenth century prisons and criminal courts, to provide a truly comprehensive profile of the common reader at a time of cheap print and rising literacy rates.

Click here to return to the beginning of this course and select another essay to read.

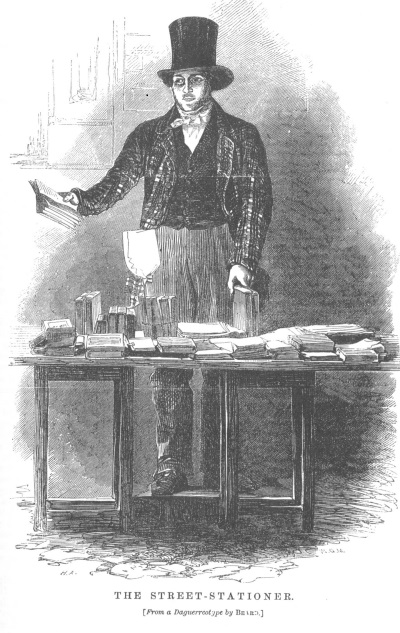

The street stationer from Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (London, 1861)

Conclusion

This free course provided an introduction to studying literature and creative writing. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Sam Howzit in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Figure 2: Nicholas Byfield by William Richardson, 1790, stipple and line engraving, © National Portrait Gallery

Figure 3: Harriet Martineau by Richard Evans, oil on canvas, exhibited 1834, © National Portrait Gallery

Figure 4: Charles Dickens (1812-1870) about the age of 50, photographed by Mason & Co., c. 1862, © Charles Dickens Museum, London

Figure 5: Oliver asks for ‘more’, illustration for ‘Character sketches from Dickens’, compiled by B.W. Matz, 1924 (colour litho), Private collection/Bridgeman Art

Figure 6: Mr Pickwick addresses the club, illustration from The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (1812-1870), published 1837, litho, Hablot Knight Browne (1814-1892), Private collection/ Bridgeman Art

Figure 7: Anne Thackeray Ritchie by Julia Margaret Cameron, albumen print, circa 1867, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 8: The Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales, by George Dawe, 1817, oil on canvas, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 9: Mark Twain, by London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company, albumen carte-de-visite, 1870s, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 11: Portrait of Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855) by George Richmond (1809-1896) and engraved by Walker and Boutall, Private collection/ The Stapleton Collection/ The Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 12: Charlotte Brontë working on Jane Eyre (litho), English school, Private collection/ The Stapleton Collection/ The Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 13: Molly Hughes (1866-1956), The Library Thing

Figure 14 Cassell’s Family Magazine, November 1897, www.philsp.com/ data/ images/ c/ cassells_family_189711.jpg

Figure 15: Australian soldiers resting on their way to the Front, September 1917, Trustees of the National Library of Scotland

Figure 16: A Scottish soldier reading a letter while on gas sentry duty near the trenches, Trustees of the National Library of Scotland

Figure 17: The Circulating Library, Isaac Cruikshank (1764-c.1811), pen and ink and water colour and wash on wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, USA/ The Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 18 Hall’s Library at Margate, 1789 (coloured engraving), Thomas Malton (1748-1804), Private collection/ The Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 19: The Travelling Companions by Augustus Egg, © Bridgeman Museums and Art Gallery

Figure 21: Samuel Pepys by John Hayls, 1666, © National Portrait Gallery

Figure 23: Robert Louis Stevenson at his desk, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University