Veiling

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 2 March 2026, 6:26 PM

Veiling

Introduction

This course explores controversies associated with the practice of ‘veiling’ within Islam. The Islamic ‘veil’, be it in the form of the hijab, niqab, jilbab or burqa (we shall explore this terminology in more detail later), has been at the centre of many different controversies. Within the European and North American context, public debates around ‘veiling’ often evoke stereotypical images associating the Islamic ‘veil’ with ‘gendered oppression’, political and/or religious extremism, ‘otherness’, refusal to be a ‘good citizen’ and irreconcilable difference between ‘the modern West’ and ‘Islam’ (Sinclair, 2012). ‘Face-veils’ in particular have also been condemned on the grounds of perceived security, health and safety issues or the need to clearly identify the wearer. In other contexts, particular styles of ‘veiling’ are culturally regarded as the ‘norm’ and are socially expected. In some countries, such as Iran, particular forms of ‘veiling’ are legally enforced in public spaces, and political leaders stereotypically associate ‘veiling’ with decency, dignity, respectability and responsible citizenship, and present women’s decision not to ‘veil’ as indecent, immoral, undignified, ‘un-Islamic’, anti-social and so on. As the sociologist and anthropologist Annelies Moors points out, ‘what is perhaps most striking is the force with which politicians feel the need to fix the meanings of items of dress Muslim women wear’ (2010, p. 112). Or, as Reina Lewis, Professor of Cultural Studies at the London School of Fashion, puts it: ‘The veil […] is a garment fought over by adherents and opponents, many of whom claim their understanding of the veil’s significance is the one and true meaning’ (2003, p. 10).

The discrepancy between one-dimensional representations of the ‘veil’ in many public debates and the multifaceted, complex ‘reality’ of ‘veiling’ practices has led to many misunderstandings and has been the source of many controversies. In comparison with other pieces of clothing, interpretations of the symbolic meaning of the ‘veil’ and of ‘veiling’ practices seem to be particularly diverse and contested, among both non-Muslim and Muslim men and women. However, it is important to remind ourselves that apart from fulfilling practical functions, such as comfort, warmth and protection from the sun or from rain, every piece of clothing is loaded with symbolic meaning. The interpretation and careful negotiation of dress codes pose everyday dilemmas for many people and are clearly not limited to Muslim women. What to wear or not to wear is a decision most people face on a daily basis across the world within very different contexts, and this decision can be influenced by a vast range of different factors and can provoke a wide range of different reactions. Apart from financial constraints and consideration of weather conditions, there are complex sets of norms, social expectations and notions of what is considered to be socially acceptable or fashionable that influence what we wear and what we expect others to wear. Wearing a bikini or pyjamas to work in an office is, for example, likely to raise some eyebrows and could even cost you your job. As the anthropologist Emma Tarlo points out:

we have certain sort of norms of acceptability of dress within the public sphere. And although we consider in the West that we are very individualist and we all choose what we wear, if we actually go out into the street, we see that people actually are wearing a very limited range of things. And a huge number of people are wearing denim jeans, which I think is the most popular item of clothing in the world now.

Social norms and expectations vary in different cultural, geographical and social contexts and are often subject to change within different historical periods and between different generations. The great popularity of denim jeans across the world is, for example, a relatively recent phenomenon.

Wider and intense examination of decisions made in response to the daily dilemma of what to wear ‘can reveal much about society, history, politics, culture and, above all, the way in which people seek to express their own identity’ (Tarlo, 1996, p. 1). As the novelist and academic Alison Lurie argues in her book The Language of Clothes:

Long before I am near enough to talk to you on the street, in a meeting, or at a party, you announce your sex, age and class to me through what you are wearing – and very possibly give me important information (or misinformation) as to your occupation, origin, personality, opinions, tastes, sexual desires and current mood. I may not be able to put what I observe into words, but I register the information unconsciously; and you simultaneously do the same for me. By the time we meet and converse we have already spoken to each other in an older and more universal tongue.

Anthropological, sociological, historical and psychological approaches to the study of dress and clothing acknowledge the particular significance assigned to headwear in cultures across the globe as ‘a tactical marker of ethnicity, status, social cohesion, political affiliation, fashionable tastes and ethnic, national or group membership’ (Maynard, 2004, p. 201). It has also been stressed that ‘clothing is one of the most consistently gendered aspects of material culture’ (Burman and Turbin, 2003, p. 1). As a form of headwear and clothing, the ‘veil’ represents visual and tangible expressions of political, social and religious ideas, notions of gender and of lived religion. The study of the interpretation and use of this controversial garment can give us important insights into the fascinating interaction between dress, religion and culture.

This course explores how and why Muslim women wear ‘veils’ today, and how they negotiate complex social and legal rules and practical challenges associated with wearing or not wearing ‘veils’ within the context of contemporary societies. It highlights the diversity and complexity of different styles and interpretations of this controversial piece of clothing. In the following section, some relevant terminology that is used to refer to different styles of ‘veiling’ is explored. The course then moves on to consider a range of different factors that can influence why women do or do not wear ‘veils’ or adopt particular styles of ‘veiling’. The section on ‘Hijab and sport’ then looks at how Muslim women negotiate the practical challenges of leading an active lifestyle while wearing ‘veils’. In the section ‘Hijab and fashion’, the role of the ‘veil’ within the context of the emergence of an increasingly wide variety of interpretations of ‘modest fashion’ is explored. The final section considers the issues raised within this course in the specific local context of contemporary Kerala in India, particularly the city of Kozhikode (also known as Calicut).

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A332 Why is religion controversial?.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

demonstrate skills in the analysis of visual and material expressions of religion

understand the role of material culture within religious rituals and practices

recognise the complexity and diversity of the many different styles of ‘veils’ and ‘veiling’ practices in Islam and of the range of different factors that can influence the adoption and interpretation of different ‘veiling’ practices and styles of dress among Muslim women

understand the limitations of the terms ‘veil’, ‘Muslim clothing’ and ‘Islamic dress’ and use some relevant terminology to distinguish between different styles of ‘veiling’.

1 Different styles of ‘veiling’

In this section we are going to explore different styles of ‘veiling’ and introduce you to some relevant terminology.

Activity 1

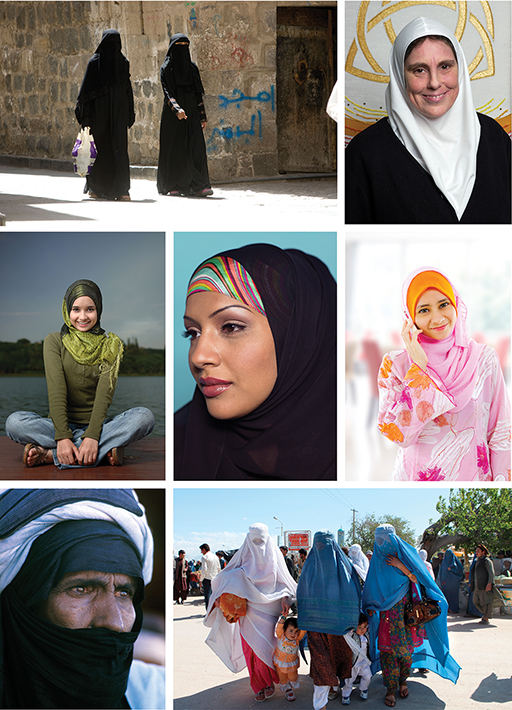

Take a look at the images in Figure 1 and consider differences and similarities between them.

This figure consists of seven photographs illustrating different styles of veiling.

On the top row, there are two photographs. The first shows two women with their whole bodies (including their heads and faces) veiled in black garments carrying shopping bags. One of the women also has her eyes covered. The second photograph shows a close-up of the face of a smiling middle-aged woman, with a white veil covering her neck and hair (though some of the hairline on her forehead can be seen) and a black loose-fitting top that also covers her neck and shoulders.

On the middle row, there are three photographs. The first shows a smiling young girl sitting in a cross-legged position, wearing jeans, sandals, a green long-sleeved top and a headscarf in different shades of green that is covering her hair and draped across her neck and shoulders. The second is a close-up photograph of the face of a young woman, wearing a veil covering her hair and neck. Two different layers of veils are showing. The woman’s forehead is covered with a bright multi-coloured piece of cloth, while her hair and neck are covered with a smart black veil. She is wearing make-up and has a pensive expression on her face. The third photograph shows a young woman wearing a loose-fitting pink/orange flowery top and a multi-layered headscarf that matches the colours of her top (the bottom half of her outfit is not shown). She appears to be speaking on a mobile phone.

On the bottom row, there are two photographs. The first photograph shows someone wearing a veil that consists of several layers of black, white and blue cloth draped around their head. The mouth and forehead are covered, but the eyes, cheekbones and nose of the weathered face are showing. The second photograph shows a row of three women, holding the hands of two toddlers and walking along in a public square, carrying shopping bags. The women are wearing loose-fitting outer garments that cover their heads, faces, eyes and upper bodies. Two of these garments are blue and one is white, and the clothes the women are wearing underneath these outer garments are very colourful.

Discussion

These images show examples of different styles of ‘veiling’, covering different parts of the body (while all of them cover the hair, ears and neck, some of them also cover the whole body and/or face), using different materials, colours and patterns. You might have assumed that they are all photographs of Muslim women. However, the picture on the right of the top row actually shows an Orthodox Christian nun, and the picture on the bottom left shows a veiled man (a member of the Muslim Berber group, the Tuareg, where this type of ‘veil’ has traditionally been worn by noblemen).

It is important to bear in mind that ‘veiling’ practices have existed in many different cultural, religious, geographical and historical contexts and have been adopted by both men and women. There is a wide range of different styles of ‘veils’ and varieties of ‘veiling’ practices. Before we engage more deeply with the study of different styles and practices of ‘veiling’, it will therefore be helpful to look at some relevant terminology. You may have noticed that in the first part of this course I have put the words ‘veil’ and ‘veiling’ in inverted commas. I have done this because there are certain limitations associated with the use of these terms. Some of these limitations are explored in the following reading, where the anthropologist Fadwa El Guindi critically engages with the origins and meanings of the word ‘veil’, explains the limitations of the use of this term, and highlights the diversity and complexity of the practices that the concept of ‘veiling’ is referring to.

‘Veils’ and ‘veiling’

Activity 2

Now read an extract from Fadwa El Guindi’s book Veil: Modesty, Privacy and Resistance (1999). This is Reading 1. As you read this text, consider what kind of pre-conceived ideas you yourself might have regarding the meaning of the terms ‘veil’ and ‘veiling’, and what the limitations of the use of these terms might be.

Reading 1

Source: El Guindi, F. (1999) Veil: Modesty, Privacy and Resistance, Oxford/New York, Berg, pp. xi–xii, 6–7; footnotes omitted.

Veil was not my original choice for this book’s title. For a number of reasons my original intent was to write a book about Hijab, the word in the Arabic calligraphic art on the cover. ‘Veil’ has no single Arabic linguistic referent, whereas Hijab has cultural and linguistic roots that are integral to Islamic (and Arab) culture as a whole. But the publisher preferred Veil to Hijab for reader accessibility and familiarity. From a marketing angle, the publisher rightly finds Veil more marketable, even sexy. I was not persuaded by the marketing argument.

As I reflected further on the matter I realized that my own resistance to using the word ‘veil’ stems from the same bias that entraps many scholars. The veil is avoided as a subject of study because of what it stands for ideologically or for its association with Orientalist imagery. And while the word ‘veil’ is found in many – too many – titles, scholarly discussion of it occupies a few pages, even paragraphs, in most works. In most, the veil is attacked, ignored, dismissed, transcended, trivialized or defended. This reaches hysterical proportions in the media, where a hostility has developed against the veil (often under the guise of humanism, feminism or human rights) from Saudi Arabia (after the Gulf War contact) to Iran (after the Islamic Revolution), and is now concentrated on the Taliban as they consolidate their power over Afghanistan. Much of what is said is ethnocentric (often a personalistic vision reflecting the fears of the authors) and shows no understanding of how such movements are contextualized in global politics – the rise of the Taliban, for instance, being a product of the CIA’s activities during its struggle against the Soviet Union in the Cold War period. This bias, and misinformation, also prevented a full anthropological analysis, thus further hindering an adequate understanding of the veil, its roots, and its meaning in its sociocultural context.

I came to realize during the course of my research on the subject that veiling is a rich and nuanced phenomenon, a language that communicates social and cultural messages, a practice that has been present in tangible form since ancient times, a symbol ideologically fundamental to the Christian, and particularly the Catholic, vision of womanhood and piety, and a vehicle for resistance in Islamic societies, and is currently the center of scholarly debate on gender and women in the Islamic East. In movements of Islamic activism, the veil occupies center stage as symbol of both identity and resistance.

[…]

Etymology of Veiling

The English term ‘veil’ (like its European variants, such as voile in French) is commonly used to refer to Middle Eastern and South Asian women’s traditional head, face (eyes, nose, or mouth), or body cover. As a noun veil derives, through Middle English and Old North French, from the Latin vēla, pl. of vēlum. The dictionary meaning assigned to it is ‘a covering,’ in the sense of ‘to cover with’ or ‘to conceal or disguise.’ As a noun, it has four usages: (1) a length of cloth worn by women over the head, shoulders, and often the face; (2) a length of netting attached to a woman’s hat or headdress, worn for decoration or to protect the head and face; (3) a. The part of a nun’s headdress that frames the face and falls over the shoulders, b. The life or vows of a nun; and (4) a piece of light fabric hung to separate or conceal or screen what is behind it; a curtain.

In another reference source the range of meanings under ‘veil and veiling’ is organized under several broad headings: A. Interpersonal Emotion: (1) celibacy; (2) covering in the sense of cover; (3) covering in the sense of shade; B. Modes of Communication; (1) hiding in the sense of disguise; (2) concealment, conceal, or concealed; (3) deception, sham; C. Organic Matter: (1) screen; (2) invisibility; (3) dimness; (4) darkness; (5) dim sight. The final category is D. Dressing in ‘Space and Dimensions.’ It is interesting that ‘veil as dress’ is last on the list of significations. There is a separate grouping called Religion: Canonicals that includes vestures; covering; seclusion; monastic; occult. (On ‘Veil of Veronica’ see Apostolos-Cappadona 1996).

In sum, the meanings assigned in general reference works to the Western term veil comprise four dimensions: the material, the spatial, the communicative, and the religious. The material dimension consists of clothing and ornament, i.e. veil in the sense of clothing article covering head, shoulders, and face or in the sense of ornamentation over a hat drawn over the eyes. In this usage ‘veil’ is not confined to face covering, but extends to the head and shoulders. The spatial sense specifies veil as a screen dividing physical space, while the communication sense emphasizes the notion of concealing and invisibility.

‘Veil’ in the religious sense means seclusion from worldly life and sex (celibacy), as in the case of the life and vows of nuns. This Christian definition of the Western term ‘veil’ is not commonly recognized. Although evidence shows that the veil has existed for a longer period outside Arab culture, in popular perception the veil is associated more with Arab women and Islam.

In Arabic (the spoken and written language of two hundred and fifty million people and the religious language of one and a half billion people today) ‘veil’ has no single equivalent. Numerous Arabic terms are used to refer to diverse articles of women’s clothing that vary by body part, region, local dialect, and historical era (Fernea and Fernea 1979: 68–77). The Encyclopedia of Islam identifies over a hundred terms for dress parts, many of which are used for ‘veiling’ (Encyclopedia of lslam 1986: 745–6)

Some of these and related Arabic terms are burqu’, ‘abayah, tarhah, burnus, jilbab, jellabah, hayik, milayah, gallabiyyah, dishdasha, gargush, gina’, mungub, lithma, yashmik, habarah, izar. A few terms refer to items used as face covers only. These are qina’, burqu’, niqab, lithma. Others refer to headcovers that are situationally held by the individual to cover part of the face. These are khimar, sitara, ‘abayah or ‘immah. To add to this complexity, some garments are worn identically or similarly in form by men and women, and the same term is used in both cases. Some are dual-gendered while others are neutral-gendered. For example, both women and men wear outer garments such as cloaks and face covers (L. Ahmed 1992: 118; El Guindi 1995b). As an example, lithma is the term for a dual-gendered face cover used in Yemen by women and associated with femaleness, yet it is also worn by some Bedouin and Berber men and associated with virility and maleness. Other examples include the neutral-gendered terms ‘abayah or ‘aba of Arabia and burnus of the Maghrib – overgarments for both sexes.

All this complexity reflected and expressed in the language is referred to by the single convenient Western term ‘veil,’ which is indiscriminate, monolithic, and ambiguous. The absence of a single, monolithic term in the language(s) of the people who at present most visibly practice ‘veiling’ suggests a significance to this diversity that cannot be captured in one term. By subsuming and transcending such multivocality and complexity we lose the nuanced differences in meaning and associated cultural behaviors.

Discussion

The terms ‘veil’ and ‘veiling’ might have different associations for you, or you might prefer different terms based on your own background or experiences. El Guindi’s text reflects my own reservations against using the terms ‘veil’ and ‘veiling’, as they do not do justice to the many different styles and materials used and to the complexity, diversity and fluidity of ‘veiling’ practices. El Guindi highlights the ‘indiscriminate, monolithic, and ambiguous’ nature of these terms (1999, p. 7). Nevertheless, I decided to use ‘veiling’ as the title of this course as it forms a familiar point of reference for many people in European and North American contexts. I also find it useful precisely because it is so unspecific and can be applied to so many different practices within different historical, cultural and geographical contexts. Equally, the term ‘veil’ can be used to describe a wide range of materials and styles. However, when using the terms ‘veil’ or ‘veiling’, we need to bear in mind their limitations and ambiguity.

Notions of ‘Islamic dress’ or ‘Muslim clothing’ are no less complex and ambiguous. As the writer, researcher and activist Aisha Lee Fox Shaheed points out in the next reading, the use of these terms also needs to be carefully considered.

‘Islamic dress’ and ‘Muslim clothing’

Activity 3

Now read an extract from Aisha Lee Fox Shaheed’s article ‘Dress codes and modes: how Islamic is the veil?’ which was published in The Veil: Women Writers on its History, Lore, and Politics (2008), edited by Jennifer Heath. This is Reading 2. As you read this text, consider the following question:

Why does Shaheed question the use of the terms ‘Islamic dress’ or ‘Muslim clothing’, and the way that the ‘veil’ has been associated with these terms?

Reading 2

Source: Shaheed, A.L.F. (2008) ‘Dress codes and modes: how Islamic is the veil?’, in Heath, J. (ed.) The Veil: Women Writers on its History, Lore, and Politics, Berkeley/Los Angeles/London, University of California Press, pp. 290–3, 295, 303; footnotes omitted.

If [man] orders us to veil, we veil, and if he now demands that we unveil, we unveil … [man may be] as despotic about liberating us as he has been about our enslavement. We are weary of his despotism.

‘Do they make you veil?’

It’s a question I’m frequently asked when people hear I’m travelling to visit family in Pakistan. It has always caught me off guard. No individual, religion, or state has ever dictated that I – as a secular person of mixed heritage – must veil. Nonetheless, when the subject of Muslim women’s clothing arises, the discussion inevitably veers toward the veil.

Given the profound differences between styles of dress and conceptions of female modesty across Muslim communities – from northern Nigeria to Uzbekistan, the suburbs of Paris to Indonesia – I find the terms ‘Islamic dress’ or ‘Muslim clothing’ ironic, as if there were a singular uniform prescribed by Islam… .

My grandmother is an Indian Muslim who migrated to the newly created state of Pakistan following the partition of 1947. To me, a Muslim woman always wore a sari and covered her head only when she prayed in the privacy of her room. In downtown Karachi, I was well aware of the variety of women’s clothing within the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, from the baggy and brightly colored salwar kameez (trousers and tunic) worn by Muslims, Christians, and Parsis (South Asian Zoroastrians) to neutral-colored cloaks that we call arabis, and face veils.

As a child, I asked my grandmother if she had ever worn a veil and was laughingly told how she and her sisters were among the first generation of Muslim girls in Lucknow to go to college, a move encouraged by their father. He permitted all his daughters to study, reminding them that their behavior would be the key to whether other young women of the community would be allowed out subsequently. My great-grandfather did not want his daughters to veil their faces, although as the first women to attend the previously all-male Muslim University at Aligarh, they donned the Indian-style burqa (a slim black cloak); so they did not veil. In order to reach the college, my grandmother and her sisters had to ride bicycles through the crowded market: a foray into public space that, even for the most liberal of Muslim Indians at the time, required girls to dress modestly. With their heads covered by their dupattas, they cycled to school and attended lectures in classrooms where the female students sat at the back behind a black curtain…

The thought of my grandmother in a burqa is foreign to me. No one in our family now ever covers their heads or faces. When I asked my grandmother why, she replied, ‘We did so you wouldn’t have to.’

My great-grandfather, she explained, had not supported the cloistering of women, which in South Asia is called purdah or chadri aur chardivari (literally, a curtain and four walls). Of greater importance to him was that his daughters become educated to the same degree as his sons, and this would require them to leave the home and participate in public. By veiling for a specific period of time, related to their daily routine and their life stage as unmarried women, my grandmother and her sisters were able to overturn social norms by attending college and to observe the sanctities of public space or private honor. For our family, veiling was tied to our identity as a religious minority in India and symbolized familial honor but was never viewed as a religious injunction or a requirement of Islam.

Every person with Muslim heritage has a different experience, precisely because what we wear – including the veil – depends on our specific culture(s), the historical moment, and prevailing conceptions of female modesty and sexuality. Islam, like most religions, has been interpreted in different ways across communities, and what is deemed appropriate clothing for women varies accordingly. Whether Islam requires women to cover heir heads and/or faces is perhaps less pertinent to women’s lived experiences than whether their families, local religious authorities, and government require them to cover themselves. For this reason, contemporary debates around the veil should begin with politics rather than theology, as both state-level and nonstate groups further their own agendas by exercising control over people’s clothing in the name of religion, culture, and authenticity. In the context of Muslim women, this control can be played out through the imposition, or the banning, of the veil.

[…]

What may be assumed to be acceptable Muslim clothing in one place may not be so in another. In Tunisia, women are liable to undergo police intervention if they veil, while in Saudi Arabia, they are punished if they do not. This suggests that we should broaden our scope away from notions of a single ‘Islamic culture’, to encompass women in multiple Muslim contexts: in Islamic states, in secular Muslim-majority states, in Muslim families and communities in the diaspora, among migrant Muslim communities, for non-Muslim women who are subject to Muslim laws because of their country of residence or their children’s, and for women who do not identify as Muslim but who are automatically catergorized as such because of their family heritage or the laws of their country.

[…]

By equating dress codes with religion we obscure the fact that clothing worn my Muslims is as varied and culturally specific as clothes worn by Jews, Buddhists, or atheists. A politically informed analysis moves us beyond theological debates (an arena where women are structurally disadvantaged in any respect) and into the realm of lived experience.

I’m asked, ‘What do you wear in Pakistan?’ and I hastily explain that I’m not representative of Pakistani womanhood, because of my hybrid outfits: blue jeans, a tunic-style kurta, and a bare head. But then I pause. Is my grandmother’s sari, accompanied by European high heels, more authentic than my blue jeans? Is that designer blouse any less traditional than the black arabi that covers it? Long flowing skirts have been worn by the nomadic women of the Punjab for centuries, but does that make them more Pakistani than the increasing number of women in face veils I encounter each time I visit downtown Karachi? My grandmother’s generation is the last to remember Pakistan it is infancy: a new state predicated upon secularism, diversity, and equity. She veiled so I wouldn’t have to …. What can I do for future generations of girls and women who are taught that Islam requires women to cover themselves without denying the Muslimness of a Muslim woman’s sari?

Searching for authenticity will always prove elusive, but a thorough excavation of our histories – through the colors of our creativity and the dark moments of control – unmasks the forces that dictate how we clothe our bodies for the world.

Discussion

Shaheed highlights the diversity of different dress codes and of changing notions of ‘appropriate’ or preferred clothing across different generations and within different cultural, historical and political contexts. She believes that this diversity is often neglected and points out that ‘Islamic’ dress codes are often perceived as more clear-cut and homogeneous than they ‘really’ are in people’s lived experiences. In particular, she challenges the stereotypical association of the ‘veil’ with Muslim women’s dress codes on the basis that ‘veiling’ practices exist in many different religious traditions and that many Muslim women do not wear a ‘veil’. Shaheed even goes as far as to question the use of the notion of ‘Islamic dress’ or ‘Muslim clothing’ altogether. Her argument that local cultural and political factors are more important than theological or religious factors in influencing women’s dress codes is, of course, open to debate and depends very much on how the notions ‘religion’ or ‘religious factors’ are defined. We shall come back to this later, but you might want to keep this argument in mind during the following readings and activities.

It should also be noted that it was not only Indian or Pakistani universities, like the Muslim University of Aligarh mentioned in Reading 2, that were initially restricted to men and only gradually opened their doors to women. In the UK the University of Cambridge, for example, did not accept women as full members until 1948, though women were admitted (on a restricted basis) in the late nineteenth century. You might also have noted that the situation in Tunisia that Shaheed describes has changed since the Arab Spring in 2011, when the official ‘headscarf’-ban was lifted.

Terminology

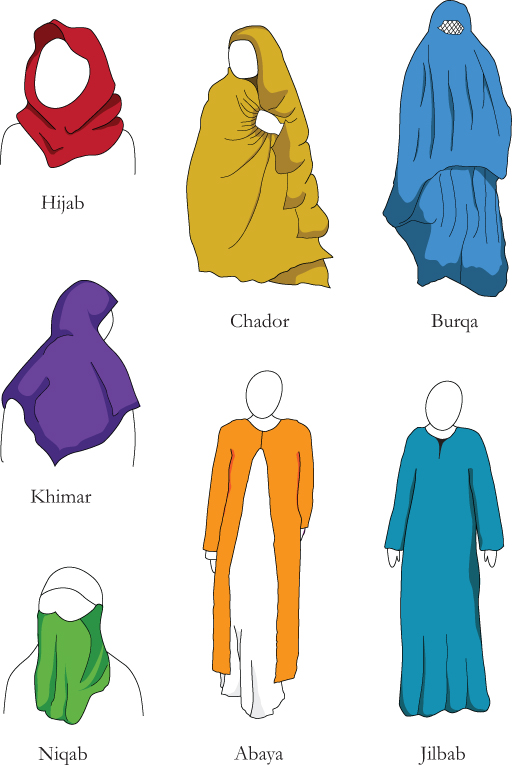

The previous readings have drawn attention to the limitations of the terms ‘veil’, ‘Muslim clothing’ or ‘Islamic dress’. Figure 2 illustrates some of the terminology that has been used to describe different styles of veiling adopted by Muslim women and shows some examples of these styles. However, when considering such images, we should bear in mind that the distinction between different styles of veiling is often fluid and that many Muslim women choose not to wear a veil at all. Furthermore, all of the styles pictured have many different variations and come in a myriad different colours and shapes. The use of these terms can also vary in different regional contexts, or among different social groups. Finally, you will find that, because these words are derived from other languages, they are sometimes spelled differently in English. On the following pages, this terminology will be explored in some further depth and detail.

This figure shows simple drawings illustrating examples of different styles of veiling, including a hijab, chador, burqa, khimar, niqab, abaya and jilbab. These different styles of veiling are described in Section 1 of the course.

- Abaya is an Arabic term for a long, loose outer garment. Abayas are worn by both men and women.

- Burqa is an Arabic term for a loose-fitting garment (or a combination of different garments worn together) covering the head, face and body, and sometimes – though not always – the eyes.

- Chador is a Persian term for a full-body-length cloak that covers the hair and body. It is open at the front and is held together by the wearer’s hands or tucked under her arms.

- Hijab is an Arabic term that is mentioned in the Qur’an, where it refers to a curtain, separating spaces. It is frequently used nowadays as an umbrella term to refer to Muslim clothing in general. However, particularly in the European and North American context, it is often used to refer to headscarves worn by Muslim women that cover the hair and neck, but leave the face free. The different uses of this term are further explored below.

- Jilbab is an Arabic term for a long, loose outer garment, which is worn by both men and women. It is a term that is used in the Qur’an. The distinction between jilbab and abaya is not very clear-cut, as both can take many forms, but jilbabs are usually closed at the front, while abayas tend to be open, but can be pulled together.

- Khimar is an Arabic term for a veil that covers the hair, neck and shoulders, but not the face. It is a term that is mentioned in the Qur’an.

- Niqab is an Arabic term describing a face-veil that covers the lower half of the face, but leaves the area around the eyes clear. It is worn with an accompanying headscarf, and sometimes with a separate veil covering the eyes.

As noted above, the term hijab is often associated with a particular style of veiling: a headscarf covering the hair and neck. While the word is generally used in this way, particularly in the European and North American context, it is important to bear in mind that it also refers to concepts of covering and modest clothing, and to abstract notions of privacy or morality in a wider sense. Faegheh Shirazi, a scholar of Middle Eastern studies, summarises the different meanings of the concept of hijab as follows:

The morphology of the word hijab in the Arabic language is from hajaba, meaning to veil, cover, screen, shelter, seclude (from); to hide, obscure (from sight); to eclipse, outshine, overshadow; to make imperceptible, invisible; to conceal (from); to make or form a separation (between). As evident from the wealth of meanings of the term hijab, we can conclude that the word hijab can be understood in numerous ways depending on a given situation based on culture. Generally in popular Islamic culture, hijab is understood in two specific forms: 1) concealment donned by women as a religious obligation mentioned in the holy Qur’an with its various stylistic interpretations, and 2) as practiced or understood by Muslim women in various societies. In this regard, one finds variations in styles of veils adopted by women within the same culture. Thus we can not claim there is a ‘uniform’ style of hijab that is common among women in Islamic cultures.

In Asia, the term pardah (or purdah) is often used in a similar context, though it is not restricted to Muslim women:

The term comes from the Persian word, ‘parda’, meaning ‘curtain’. It initially referred to the hanging separating the women’s quarters in a house from men’s. Its meaning now covers a whole range of different ways of separating off female from male space, of ensuring that women do not come into contact with inappropriate men. These ways may be spatial, physical, behavioural and/or attitudinal: withdrawing into the women’s quarters, veiling, keeping eyes downcast, behaving in a modest way and so on (Kahn 1999). Purdah practices thus include, but are not restricted to, forms of dress.

The terms used to describe different styles of veiling in Figure 2 can be interpreted in many different ways, and some of the distinctions between these styles cannot be clearly drawn. Just type ‘hijab’ or ‘burqa’ into an internet search engine (such as Google) and look for relevant images, and you will see the vast range of different styles, materials and colours that are shown in these images. It is also important to bear in mind that veils are not static or fixed items, but tend to be made from soft, flexible fabrics that can be fairly easily adjusted, straightened, folded up, lifted or pinned up, lowered down, pulled together or tucked in. This means that it can be relatively easy to shift between different styles of veiling in different social situations. The notion of a hijab or cover also often goes beyond a headcover and can relate to other pieces of clothing, such as a jilbab or abaya. As becomes apparent in the list of definitions above, there are a range of Arabic terms (such as jilbab, niqab, abaya, burqa, hijab and khimar) and Persian terms (such as chador) for these garments. These terms have been used in many different cultural, geographical and historical contexts, and preferences for their use vary in different contexts. Burqa is, for example, originally an Arabic word, but it is now very rarely used in countries where Arabic is spoken as a first language. Instead it is now predominantly used in Pakistan and Afghanistan (and in western European mainstream media and political debates). There are also different preferences between different generations. For instance, at the time of writing, younger generations in Pakistan tend to prefer the word hijab (as its use has recently become more widespread globally), but older generations often prefer chador (Bokhari, 2012; 2013). It has also been argued that approaches to veiling have often been influenced by local customs that are not directly related to Islamic traditions. The Oxford Dictionary of Islam maintains:

The practice [of wearing a hijab] was borrowed from elite women of the Byzantine, Greek, and Persian empires, where it was a sign of respectability and high status, during the Arab conquests of these empires. It gradually spread among urban populations, becoming more pervasive under Turkish rule as a mark of rank and exclusive lifestyle.

The existence of such a wide variety of different approaches to veiling within Islam is also due to the fact that there are different schools of thought among Muslim scholars as to how notions of ‘modesty’, ‘decency’ and ‘purity’ should be understood, and as to whether covered dress in public should be regarded as a religious duty and, if so, which parts of the body should be covered. There are also different views on the extent to which women’s covered dress serves to protect women from being molested by men, and on whether women need to cover themselves in order to protect men from temptation. However, it is important to note that modesty and freedom from vanity are ideals that apply to both Muslim men and women in Islamic thought, and that both Muslim men and women are expected to dress modestly in public (‘Modesty’ in Esposito, 2003).

Activity 4

Now read an extract from Women in Islam (2001) by Anne Sophie Roald, a historian of religion. This is Reading 3. In this text she lists the four different passages from the Qur’an that describe appropriate behaviours for men and women outside their immediate families and make reference to different types of covering or veiling. As you read the text, consider the following question:

What do the extracts quoted in the reading tell us about how Muslim women should dress in public?

Reading 3

Source: Roald, A.S. (2001) Women in Islam: The Western Experience, London/New York, Routledge, p. 255.

There are four passages in particular in the Koran which are regarded as dealing with behaviour between men and women who mix outside kinship bonds:

Tell the believing men to lower their gaze and to be mindful of the chastity [guard their private parts]. This will be the most conducive to their purity. Verily, God is aware of what you do.

And tell the believing women to lower their gaze and to be mindful of their chastity [guard their private parts], and to not display their adornment beyond what may [decently] be apparent thereof. Let them draw their covering [khumur; sing. khimār] over their bosoms and let them not display their adornments to any but their husbands, or their fathers … Let them not stamp their feet so as to reveal what they hide of their adornments. O believers, turn unto God all of you so that you may succeed (K.24: 30–1).

Women, advanced in years, who do not hope for marriage, incur no sin if they discard their garments (thiyābahunna), provided that they do not aim at a showy display of their charm. But it is better for them to abstain from this. God is All-hearing All-knowing (K.24: 60).

O Prophet! Tell you wives and your daughters and the wives of the believers, that they should draw over themselves some of their outer garment (jilbāb). That will be better, so that they will be recognised and not annoyed. God is ever Forgiving Merciful (K.33: 59)

O you who believe! Enter not the Prophet’s dwellings unless you are given leave. … And [as for the Prophet’s wives] when you ask of them anything that you need, ask them from behind a curtain (hijāb). That is purer for your hearts and for their hearts. You should not cause annoyance to the Messenger of God and you should not ever marry his wives after him. That would, in the sight of God, be an enormity (K.33: 53).

The first three Koranic passages above are directed towards women in general. The fourth passage deals with how men should behave towards the wives of the Prophet only.

Discussion

In the extracts presented in Reading 3, women are told to ‘be mindful of their chastity [guard their private parts]’ (Q. 24: 30–1), ‘draw their covering [khumur; sing. khimār] over their bosoms’ (Q. 24: 30–1), refrain from publicly displaying ‘their adornments’ (Q. 24: 30–1) and from offering a ‘showy display of their charm’ (Q. 24: 60). They are advised to ‘draw over themselves some of their outer garment (jilbāb)’ (Q. 33: 59) in order to be recognised as Muslims and avoid harassment, though exemptions are made for older women (Q. 24: 60).

The extracts mention a number of terms you have encountered in this course before: khimar, jilbab and hijab. Khimar is translated as ‘covering’ and jilbab as ‘outer garment’. The concept of hijab is mentioned specifically in relation to interaction with the Prophet Muhammad’s wives, who should be addressed from behind a curtain (hijab).

2 ‘Do they make you veil?’

After considering different styles of veiling and the terminology used to describe them, I would now like to move on to consider factors that influence why women do or do not wear veils or adopt particular veiling styles and practices. To what extent is women’s rejection or adoption of the Islamic veil (in whatever form) constrained by rules and expectations imposed on them by their families, local religious authorities, communities or governments? How much room is left for individual agency, choice and creative expression?

In mainstream media and political debates in Europe and North America, the hijab, burqa and niqab in particular have frequently been associated with the oppression of women (see, for instance, Sinclair, 2012). It is often assumed that male family members force women to veil themselves. (See, for example, Shaheed’s reference to the question ‘Do they make you veil?’ at the beginning of Reading 2.) The idea that Muslim women need to be rescued and liberated from ‘Islamic male tyranny’ has had ‘tremendous emotional appeal and longevity’ (Morey and Yaqin, 2011, p. 10). However, perhaps the issues are not as clear-cut. As Lewis points out:

In all these developments, women’s agency has been central as they struggle to deal with the myriad ways in which the figure of woman becomes symbolic for all sides of the political debate. Yet the veil is often read by the West as evidence of the very denial of women’s agency, or is over-inflated into the most important feminist struggle. But, in fact, the requirement of the veil is often least of their problems.

The British researcher Sophie Gilliat-Ray (2011) argues that a disproportionate amount of public attention has been paid to the outer appearance of Muslim women, when other issues that are of much greater concern to them are often neglected, such as access to adequate housing, education or appropriate healthcare, or help with caring responsibilities for young children and older people.

In some countries (such as Iran or Saudi Arabia) women have been expected or even forced to veil themselves, while in others (such as France, Belgium or Turkey) governments, institutions or employers have imposed bans on hijabs, burqas or niqabs. In addition to concerns regarding either the separation or the union of state and religious authorities, both veiling bans and the legal imposition of veils have often at least partly been justified on the ground that they protect and liberate women. However, they have also been criticised for limiting women’s choices and their freedom of expression. In recent years, an increasing number of young women have voluntarily adopted the veil, and many Muslim women have actively resisted the introduction and enforcement of regulations banning veils. Figure 3 shows a female university student in Turkey amid male and female police officers who are tearing off her hijab against her will as they are enforcing a hijab ban at Turkish universities. This photograph was taken in 2001, and strict regulations banning hijabs at universities in Turkey have since been considerably eased in response to public protests.

This is a photograph of a young woman surrounded by a group of people (we can see two women in uniforms, two men and the shoulders of a fifth person). One of the women in uniform is tearing off the young woman’s pink headscarf.

The understanding of the hijab as a symbol of resistance and solidarity can be traced back to the 1970s, when the hijab became increasingly regarded as ‘a symbol of public modesty that reaffirms Islamic identity and morality and rejects Western materialism, commercialism, and values’ (‘Hijab’ in Esposito, 2003). In her book A Quiet Revolution (2011) Leila Ahmed, an Egyptian American scholar of Islam and Islamic feminism, examines changing dress codes among Muslim women across the globe, with particular focus on Egypt and the USA. She argues that Egypt was the first ‘country in which the new hijab and Islamic dress had begun to appear’ (Ahmed, 2011, p. 118). It was initially adopted in the 1970s by a relatively small group of female university students who associated themselves with the Muslim Brotherhood (which you encountered in Book 1, Chapter 4), but has since spread across the world. Ahmed’s use of the term ‘new hijab’ refers to the fact that the resurgence of the hijab in Egypt in the 1970s was preceded by a period of time when ‘being unveiled and bareheaded had become the norm in the cities of Egypt, as well as in those of other Muslim-majority societies’ (Ahmed, 2011, p. 10). She also maintains that the ‘new hijab’ had relatively little resemblance to traditional Egyptian styles of veiling in terms of its style, fabric and colours (Ahmed, 2011, p. 83). She argues that ‘These garments were essentially standardized and were typically in sober solid colours, such as blue, brown and beige. […] This standardization in material and color had the effect of erasing social and economic differences between wearers’ (Ahmed, 2011, p. 83).

In this context, the hijab was used not only as a symbol of Muslim women’s public assertion of their religious identity but also of their active participation in the fight for social justice and against wealthy elites, ‘western’ imperialism and secularisation. Although in the 1970s it was a relatively small minority movement that understood the hijab in this way, in recent decades across the globe an increasing number of young Muslim women have adopted the hijab (in different styles, colours and materials) for similar reasons. For example, drawing on two decades of research on US American Muslim communities, Yvonne Haddad, a scholar studying the history of Islam and Christian–Muslim relations, observes that in the aftermath of 9/11 (the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in September 2001) ‘an increasing number of adolescents and young adults (daughters of immigrant Muslims) are assuming a public Islamic identity by wearing the hijab […] despite the fact that their mothers have never dressed Islamically’ (2007, pp. 253–4). She argues that many women have donned the hijab in response to and resistance against ‘Islamophobia that took hold as a consequence of the propaganda for the war on terrorism’ (Haddad, 2007, p. 253) and as a symbol of pride and solidarity with Muslims that have been the target of hostility, abuse or discrimination (see also Chrisafis, 2001). It is, however, important to bear in mind that there are a wide range of different, complex factors involved in why women don the hijab or adopt a particular style of veiling, and in how much choice they have in the matter.

The veil as symbol of empowerment or oppression?

Activity 5

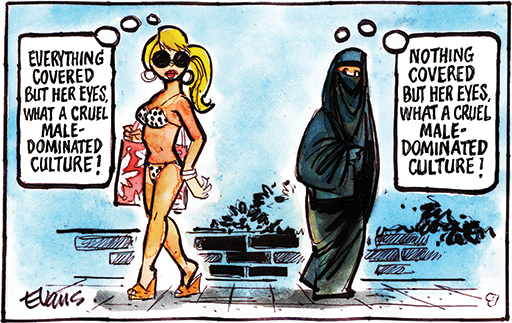

Have a look at Figures 4 and 5. Figure 4 is a cartoon that was originally published in newspapers in New Zealand (the Christchurch Press, the Timaru Herald and the Manawatu Standard) in January 2011. Figure 5 is a cartoon that was published in October 2006 in The Times.

This is a cartoon-style drawing of two women walking in opposite directions. One woman is wearing a bikini and carrying a beach bag; she is wearing high heels, jewellery and sunglasses. The other woman is wearing a black burqa covering all of her body except for her eyes. Each woman looks back at the other, and each has a ‘bubble’ telling us what they are thinking. The woman in the bikini is thinking: ‘Everything covered but her eyes. What a cruel male-dominated culture!’. The woman in the burqa is thinking: ‘Nothing covered but her eyes. What a cruel male-dominated culture!’

This is a cartoon-style drawing of two young men wearing jackets with their hoods up, as well as baseball caps and scarves under the hoods. Only their eyes are visible. They have passed a woman wearing a black burqa and carrying shopping bags. One of the ‘hoodies’ is saying to the other: ‘That’s effin’ well out of order, innit?’

- What does Figure 4 tell us about different perceptions of the burqa and the bikini, and about their association with the oppression or empowerment of women?

- How do you interpret the view of the ‘hoodie’ youths in Figure 5?

Discussion

- The two women shown in Figure 4 adopt radically different dress codes. One of them is scantily clothed in a bikini, high heels and sunglasses, while the other is wearing a black cloak covering her whole body and face – in other words she is wearing a burqa. As becomes apparent in their ‘think bubbles’, each woman regards the other as oppressed and as a victim of a ‘cruel male-dominated culture’. This cartoon highlights that it is not just the burqa that is often stereotypically associated with the oppression of women. Revealing dress codes which women are encouraged to adopt as part of ‘western’ secular mainstream culture can also be regarded as oppressive (not just by Muslims), and as a sign of the sexual exploitation and objectification of women because they put so much emphasis on physical charms and sex appeal, rather than on personality or intelligence. It also becomes apparent that neither of these two women perceives herself as oppressed; rather, each feels liberated from the constraints of the ‘male-dominated culture’ that appears to oppress the other woman.

- In Figure 5 hoodie-wearing youths express their dismissive opinion of a burqa, but seem to be blissfully unaware of the fact that their hoodies are actually remarkably similar to the burqa in terms of the way they cover their bodies and faces and are perceived controversially by many members of society – though for reasons that are different from those that lie behind the perception of burqas.

There are many different social, political, cultural and geographical factors that can influence why Muslim women adopt particular styles of veiling or do not wear a veil at all. Contrary to Shaheed’s claim in Reading 2 that ‘religious’ factors often play only a minor role in the adoption of different styles of veiling, many Muslim women stress their religious motivations. Tarlo notes that supporters of the niqab often highlight the spiritual benefits of the sense of physical closure it creates: ‘The sense of physical closure attained by the face veil operates both outwards and inwards. It has the effect of people turning in on themselves, enabling them to concentrate more fully on issues of self-discipline, self-restraint, self-mastery, devotion and prayer’ (2010, p. 151).

However, can ‘religious’ motives ever be neatly separated from politics, culture or geography? Are they not inevitably closely intertwined? It is clear that there are many contrasting points of view on the issue of veiling within Islam, and many different motives behind the adoption of different veiling practices. For some, the adoption or rejection of different styles of veiling makes them ‘unwilling targets of attention’, while others use veils as part of a ‘self-chosen visible declaration of their identity and faith’ (Tarlo, 2010, p. 1). The adoption of the niqab has been particularly controversial. Based on her analysis of forum discussions on Islamic websites, Tarlo comes to the conclusion that there are many disagreements on this issue among Muslims and that the niqab ‘has both male and female critics and supporters’ (2010, p. 150). Tarlo notes that a common theme ‘in discussions concerning niqab is the conflict between those emphasizing an individual’s religious path or duty and those more concerned with the wider social implications of niqab wearing’ (2010, p. 149).

The case studies explored in this section also highlight the fact that women can change their approaches to veiling practices at various points in their lives, adopting a range of veiling practices and investing them with different meanings in different contexts or situations. In Reading 2 Shaheed gives the example of her grandmother, who temporarily adopted the burqa to enable her to attend university. This example also demonstrates that the adoption of the hijab can open up choices and opportunities for Muslim women and can facilitate access to public space, education and work. It can enable Muslim women to observe notions of modesty without having to radically limit the range of activities they pursue outside their homes. Nevertheless, veiling practices can still pose a range of practical challenges.

3 Hijab in sport and fashion

Hijab in sport

Sport is one of the areas where wearing a hijab can pose a range of practical challenges. These challenges can be linked to the potential physical limitations of modest clothing that might restrict movement or be uncomfortable to wear during strenuous physical exercise. However, these challenges are often also tied to clothing regulations that sporting associations impose and that cannot be reconciled with modest dress codes. In some instances, Muslim women have not been allowed to compete in sporting competitions unless they remove their hijab. An example of such an incident, which caused local, national and international outrage, took place in 2007 and involved an 11-year-old girl who was ejected from a football tournament in Canada on the grounds that her hijab posed a health and safety risk, even though her supporters claimed it was safely tucked in (Adelman, 2011, p. 246). (You might note some parallels here with the Sikh motorcycle helmet controversy discussed in Chapter 1.) In the same year, the international football association FIFA introduced a ban on female players covering their heads, thus effectively excluding the Iranian women’s national football team from international competitions (Khaleeli, 2012).

In an article published in 2010 in the Sociology of Sport Journal, Nisara Jiwani and Geneviève Rail present the findings of their analysis of interviews with young Shi‘a Muslim Canadian women, focusing on how these young women combine their religious beliefs and the practice of wearing a hijab with physical activity, and how they negotiate the practical challenges that a hijab can pose during physical exercise. Jiwani and Rail establish that the majority of their interviewees felt that ‘neither the Islamic religion nor wearing the Hijab [were] barriers to participating in physical activity and some actually [felt] that participating in physical activity [made] them better Muslims’ (2010, p. 261). They come to the conclusion that their interviewees challenged the stereotype of ‘passive’, ‘oppressed’ veiled Muslim women: ‘These young Shi‘a Muslim women do not feel constrained, uneducated, tradition-bound, domestic, or victimized. They rather offer “active” resistance to the usual way in which Western discourses construct brown and/or veiled women and offer a drastically different view of “solutions” to better their lives’ (Jiwani and Rail, 2010, p. 263).

This is a photograph of a woman wearing a bright red and yellow swimsuit and swimcap. The swimsuit covers all of her body except for her face, hands and feet. She is standing on a beach holding a surfboard.

In recent years, the clothing industry has increasingly responded to Muslim women’s desire to find practical solutions that address the difficulties associated with wearing a hijab during physical exercise. This has, for example, led to the development of burqini swimwear (Figure 6) and the sports hijab (Figure 7). The Iranian-born French-Canadian designer Elham Seyed Javad designed the ‘ResportOn’ sports hijab for female Muslim athletes. It is made from antiperspirant fabric and is advertised on the resporton.com website using the tagline ‘Be yourself. Unveil your performance’. While this garment has been bought and used by Muslim women across the world, it has also attracted interest from non-Muslim women and men looking for an effective way of keeping long hair out of their faces during exercise (Qureshi, 2011). A growing number of sporting associations have begun to show greater understanding of modest dress codes and the needs of Muslim women. In 2011 the International Weightlifting Association started to allow female weightlifters to cover their arms and legs, and in 2012 FIFA lifted its ban on headcovers for female footballers (Khaleeli, 2012).

This is a photograph of a woman running on an athletics track in a big stadium. She is wearing a green and black tracksuit and a white, tightly-fitting sports hijab.

Hijab and fashion

Muslim women have shown active initiative in translating the concept of hijab into diverse veiling practices in many different ways. This can involve selecting precisely which parts of the body should be covered by the veil and adopting practical garments, such as sportswear, that conform to notions of modest dress and enable them to pursue active lives. However, women have also taken creative control of their hijabs through the use of different materials, patterns, layers of fabrics and accessories. In her observations of different styles of hijab worn on contemporary British high streets, Tarlo notes the great diversity of colours and textures women use:

Popular media representations of Muslim women swathed in black often give the impression that Islamic dress is about sombre uniformity and conformity to type. A stroll down any multicultural British high street does, however, create a very different impression. Here fashionable Muslim girls, like other young women of their generation, can be seen wearing the latest jeans, jackets, dresses, skirts and tops which signal their easy familiarity with high street fashion trends. Often the only feature of their clothing which clearly identifies them as Muslim is the headscarf, but here too, one finds much diversity. In fact, far from promoting an image of dull uniformity, the headscarf is often the most self consciously elaborated element of an outfit, carefully co-ordinated to match or complement other details of a woman’s appearance. Worn in a diverse range of colours and textures, built using different techniques of wrapping, twisting and layering and held together with an increasing variety of decorative hijab pins designed for the purpose, the headscarf has in recent years become a new form of Muslim personal art. In many cases, it provides the aesthetic focal point of a young woman’s appearance. Such scarf-led outfits, known by many as hijabi fashions, often lend a splash of colour and light to the grey uniformity of British high streets and university corridors. They also contrast strongly with some of the more austere full-length all-black covered outfits favoured by some Muslim women.

The sociologist and anthropologist Annalies Moors makes similar observations with regard to the emergence of an increasingly wide variety of interpretations of ‘modest fashion’ which is appearing in different guises in different parts of the world, often reflecting a cross-fertilisation of various cultures and styles of dress:

Such a turn towards more fashionable styles has first been recognized in Muslim majority countries, linked to the fragmentation of Islamic revival movements, the diversification of its constituencies (including upper middle-class women), and the general turn to commoditization of dress. Highly fashionable styles have emerged, which enable women to claim in one move piety, modernity, and an aesthetically sophisticated and pleasing look.

In Europe many young Muslim women have developed their own fashionable youth styles, often combining the very same items of dress as their peers, but combining and layering these in such a way that it becomes halal (Islamically permitted) fashion.

This can, on the one hand, be read as an opening for opportunities of creative expression. On the other hand, the increasing desire or need to conform to popular fashion trends and ideals could also be regarded as an added social and financial pressure on women. However, Moors comes to the conclusion that

these young women whose voices are hardly heard in public debate have indeed found alternative ways to be present in the public through sartorial styles that are far more difficult to label as signs of subjugation. Yet, whereas fashion theories have pointed to the complex ways in which markets, the cultural industry, and individual creativity are intertwined in the field of fashion, it is remarkable that in the case of Muslim women, the regime of fashion becomes so unidimensionally linked to freedom.

This sense of creative freedom is perhaps related to the fact that in Europe and North America the hijab has not yet fallen into the grasp of the mainstream fashion industry. On the one hand, this means that it is harder to access ‘modest fashion’ in high-street shops. However, since the beginning of the twenty-first century there has been a growing number of internet websites that are targeted at Muslims living in the west which market and sell modest fashion, or serve as a platform for information on how to put on a hijab or for the exchange of fashion ideas. Just type ‘hijab’ or ‘hijab fashion’ into an internet search engine, and you will have multiple hits. According to the Guardian fashion blog (2012), market research in 2012 estimated the global Muslim fashion market to be worth £59 million. While Muslim fashion is a growing business, in many European and North American countries it is still a relatively small niche market that leaves plenty of scope for small independent fashion retail businesses and room for the creative combination of a wide range of different styles and designs.

Activity 6

In this interview, Emma Tarlo (Reader at the Department of Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London) speaks about her research into Muslim women’s motivations for adopting the hijab. She considers how Muslim women combine notions of the ‘pious self’ with their interest in fashion and explores specific features of Muslim modest fashion retail. Listen to the interview now, with the following question in mind:

What kind of contested perspectives on the issue of veiling does Tarlo highlight in this interview?

Transcript: Interview with Emma Tarlo

Discussion

Tarlo highlights the wide range of diverse, contested perspectives on the hijab. She argues that media and politics tend to present the issues in terms of a direct opposition between Muslim and ‘western’ points of view and often fail to recognise the nuances and subtleties of internal debates within Muslim communities. Tarlo stresses that there are many contested perspectives on the hijab, and different understandings of notions of modest dress codes among Muslims. Key areas of tension and debate concern issues of migration and the question of whether regional, traditional forms of dress should be lost, preserved or adapted to new cultural contexts, and which styles of dress can be considered to be modest. Another area of tension explored in the interview is the contrast between notions of the hijab as a symbol of modesty and the use of the hijab as an item of adornment and a key fashion item.

4 Case study: Veiling in Kerala

To conclude your work on this course, you are going to explore some of the issues it has raised in relation to the specific local context of the city of Kozhikode (also known as Calicut) in the South Indian state of Kerala, an example of a cultural context that is very different from North America or Europe.

Activity 7

The film ‘Veiling in Calicut’ explores how Muslim women negotiate notions of choice, empowerment, piety, modesty, tradition and fashion in this specific local context. The film also provides some insight into how the local fashion retail industry has responded to the ‘pardah craze’.

As you are watching this film, pay particular attention to how the women interviewed explain when and why they have adopted different styles of hijab or pardah.

Transcript: Veiling in Calicut

Discussion

The women interviewed mention a range of different motivations for adopting different styles of veiling. Razeena says that she felt she should adopt a stricter dress code when she got married because she saw other women doing this. Razeena’s husband Auswaf argues that veiling is more of a cultural than a religious issue. Asma, by contrast, explains that she started wearing the hijab because she ‘read the scriptures’. There is reference to the fact that some women are pressurised or forced by their families to veil, but all of the women interviewed stress that this was not their experience and that donning the hijab or pardah was their own decision. Marwa argues that wearing the black pardah makes her feel protected, safe, confident and free. Asma finds wearing a hijab as a working woman ‘comfortable’.

Many of the women say that they have experimented with and adapted different styles of veiling, finding different ways of combining their wish to follow Islam and dress modestly with being stylish and with ‘the Indian way of dressing’ (Asma). Most of the women interviewed explain that they have gone through numerous shifts in their veiling styles, which were often prompted by entering a new stage in their lives, such as getting married (Razeena), going to university (Marwa), or qualifying and working as a doctor (Asma).

From the film, it also becomes clear that the women adopt different styles of dress in different social situations. There are, for example, special occasions, such as being at prayer, or attending a wedding, where special outfits are worn. The women also wear different clothes and do not wear a mafta (headscarf), pardah or hijab when they are at home with their family (without the presence of a film crew) or among female friends.

Conclusion

The study of veiling practices and dress styles adopted by Muslims in different parts of the world gives us important insights into how religion is lived and translated into everyday practices. It has become apparent that there are many different and contested perspectives on veiling practices, both among Muslim women and in relation to them. Attitudes towards veiling do not only differ between and within different geographical regions and social groups, they have also changed considerably throughout history (not just within Islam). It is not unusual for different veiling (or indeed unveiling) practices to be adopted by different generations within the same family, or even by the same person at different stages in their lives or on different social occasions. There are multiple and complex reasons why Muslim women adopt different veiling practices. These practices can have very different meanings for different people in different social, political, cultural, geographical and historical contexts: ‘in one context [it] can be a radical gesture, in another a practical garment for protection and in another environment [it] can be a sign of orthodoxy’ (Maynard, 2004, p. 201).

Changes in veiling practices and in the meanings assigned to different styles of veiling can be related to a range of cultural, political and historical developments and to a number of contested religious interpretations of the concept of hijab. Though it is a controversial practice, it has a long tradition within Islam (and beyond), bearing in mind that styles and practices of veiling have changed considerably and have been interpreted in a wide range of different ways.

Muslim women and men across the world have found many different ways of negotiating and reconciling contested interpretations of the notion of hijab with complex and diverse social and cultural influences, pressures and expectations, legal constraints, practical challenges and the desire for creative expression. This has led to the development of a vast range of different styles of veiling that have been invested with multiple, complex and contested meanings. This great diversity makes it very difficult, or perhaps impossible, to ‘pin down’ or neatly define ‘Islamic’ veiling practices and to clearly distinguish ‘religious’ factors from other social, political and cultural factors that influence veiling practices. As Reina Lewis concludes in her preface to the book Veil: Veiling, Representation and Contemporary Art:

if the secret imagined to lie behind the veil reveals one thing, it is that it cannot be contained within a single truth, experience or understanding. Instead, the veil emerges as a form of clothing that is rooted in specific historical moments and locations; its depiction is similarly contingent and its adoption, adaptation or rejection is always itself relational.

Glossary

- veiling

- See Figure 2 and ‘Terminology’ (in Section 1) for a description of different styles of veiling.

- mafta

- a term used in Kerala for a headscarf worn by Muslim women.

- pardah (purdah)

- From the Persian word for curtain, pardah refers to the practice of separating male and female space and to various forms of modest dress for women.

- salwaar (shalwaar) kameez

- This is a style of traditional dress worn by many Muslim women in South and Central Asia, though it is also worn by Hindu women in areas most affected by Muslim influence. ‘Salwaar’ refers to the trousers, and ‘kameez’ to the long shirt or tunic whose side seams are typically left open beyond the waistline. This style of dress is also worn by men; it may also be referred to as kurta-pajama. (For an example of a salwaar kameez, see Osella and Osella, 2007, p. 238, Figure 2.)

- sari

- This is a traditional garment worn by many Hindu women, but is also frequently worn by women of other religious groups from the Indian subcontinent. It consists of a long piece of cloth (of varying materials and colours) which is draped around the body in a number of different styles. It is now usually worn on top of a blouse or bodice and an underskirt.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Stefanie Sinclair.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Course image Charles Roffey in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

El Guindi, F. (1999) Veil: Modesty, Privacy and Resistance, Berg Publishers, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Shaheed, A.L.F. (2008) ‘Dress codes and modes: how Islamic is the veil?, in Heath, J. (ed.) (2008) The Veil: Women Writers on its History, Lore, and Politics, University of California Press, pp. 290–3, 295, 303.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2016 The Open University