The oceans

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 21 February 2026, 3:00 AM

The oceans

Introduction

The oceans cover more than 70 per cent of our planet. In this free course you will learn about the depths of the oceans and the properties of the water that fills them, what drives the ocean circulation and how the oceans influence our climate.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course S206 Environmental science.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

explain in your own words, and use correctly, all the bold terms in the text

identify, classify and interpret various features visible on the ocean floor

interpret temperature and salinity plots recorded in the oceans

interpret spatial maps of temperature and salinity and deduce ocean circulation

evaluate the role of the different oceans in the global ocean circulation.

1 The effect of the oceans on climate

You can see the effect of the oceans on regional climate by looking at the annual cycle of monthly air temperatures at two coastal locations at different latitudes. You might expect that the closer to the Equator, the warmer it would be. But is this the whole story?

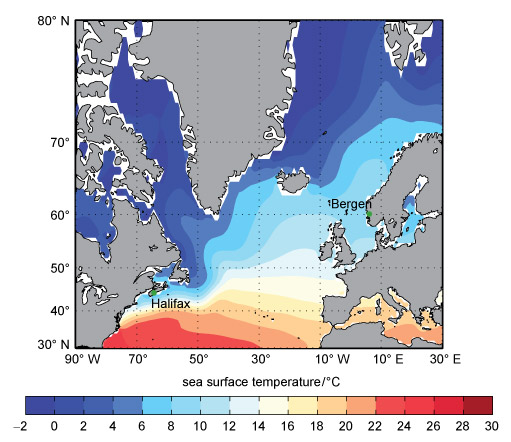

Figure 1 shows the relative locations of Bergen, Norway (60° N, 5° E) and, 1700 km closer to the Equator, Halifax, Nova Scotia (44° N, 63° W). As it is further south you might expect Halifax to be much warmer than Bergen. But you can see in Figure 2 that this is not the case.

Figure 1

This map is centred on the north Atlantic Ocean, showing ocean temperature, with blue representing colder temperature and red representing hotter temperature.

The map covers the area from the north of Greenland to North Africa and from the Great Lakes in North America to the east of the Mediterranean Sea.

Two cities are indicated on the map; Halifax, Nova Scotia in Canada and Bergen, in Norway.

There is no scale on the map but the longitude and latitude are marked and there are dotted black grid lines at the marked longitudes and latitudes.

Along the lower horizontal edge of the map, longitude is marked, from 90° W to 30° E in 20° intervals of even size.

Along the left vertical edge of the map, latitude is marked from 30° N to 80° N, in 10° intervals that are not even in size. The size of each 10° interval increases as you move north.

The key for ocean colour is provided in a horizontal bar below the map. It is labelled 'sea surface temperature/°C' and it is marked from −2° to 30° in 2° intervals. The colour changes from dark blue at −2°, through increasingly paler shades of blue to 12°. The colour then changes to yellow at 14° and the progresses through increasingly darker shades of orange to 20°,and then through increasingly darker shades of red to dark red at 30°.

The general pattern of temperature change seen is one of increasing temperature as you move from north to south, with dark blue colour dominating the waters to the east and west of Greenland and the orange /red colours restricted to a narrow band at the very south of the map.

There is also clear east west pattern noticeable and the colder temperatures extend much further south along the west side of the Atlantic, with a finger of the coldest water marked extending down as far south as Newfoundland in Canada.

The warmest temperatures maintain a more or less horizontal patterns across the Atlantic, but the contours for temperatures in the 4° to 12° range extend much further north along the east side of the Atlantic and there is a finger of paler blue protruding north along the coast of northern Scandinavia.

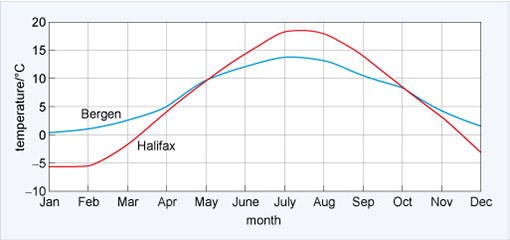

Figure 2

This line graph shows the change in mean atmospheric temperature during a year for Halifax and Bergen.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'month' and is marked from Jan to Dec in monthly intervals.

The vertical axis is labelled 'temperature/°C' and is marked from −10 to 20 in intervals of 5 °C.

There are horizontal and vertical gridlines at the axes markers.

There are two lines on the graph representing the temperature: The temperature at Bergen is presented with a blue line and the temperature for Halifax is presented with a red line.

The temperature at Bergen shows a shallow inverted 'U' shape with low temperatures in the winter months at either end of the graph and high temperatures in the summer months in the middle of the graph. The temperature starts at approximately 0° in Jan and rises steadily through 5° (Apr) to a peak of 14° (July) and then decreases steadily to 2° (Dec).

The temperature at Halifax shows a more extended inverted 'U' shape with lower temperatures in the winter months at either end of the graph and higher temperatures in the summer months in the middle of the graph. The temperature starts at approximately −6° in Jan and Feb and then rises rapidly through 5° (Apr) to a peak of 18° (July) and then decreases steadily to −4° (Dec).

-

What are the main differences between the atmospheric temperature cycles of Halifax and Bergen?

-

Halifax is warmer than Bergen in summer, but colder in winter.

The range between the maximum and minimum temperatures is also different; in Halifax it is ~24 °C (-6 °C to +18 °C), whereas in Bergen it is ~12 °C (~0 °C to +12 °C). It is only from May to the end of September that Halifax is warmer than Bergen. This arises because a vast quantity of heat is being supplied by the ocean. You can see this heat in Figure 1 because the colours representing equal sea surface temperature are not along lines of equal latitude. North of the Spanish coast water temperatures are warmer on the east side than the west. And it is a remnant of a warm water current called the Gulf Stream which flows across the Atlantic Ocean towards Northern Europe.

In subsequent sections you will see that the shape of the ocean basins (Section 2) combined with the properties of seawater (Section 3) and the ocean currents (Section 4) and the cryosphere are responsible for the Gulf Stream.

So far, you have seen how the oceans can influence regional climate. In the following sections you will investigate the reasons for this in more detail.

1.1 Summary of Section 1

- The oceans cover more than 70 per cent of the Earth.

- Heat is moved around the planet by the oceans and this heat affects regional climates.

2 Mapping the oceans

The saline oceanic water absorbs electromagnetic radiation very efficiently, so we can see very little of what lies beneath the surface. Because of this, more is known about the shape of the surface of the Moon, Venus and Mars than about Earth. In this section you will explore how the ocean basins have been mapped, and examine some of the features of the ocean floor.

2.1 Mapping the deep

Until the late 1930s the only way to measure the depth of the ocean was to use a line with a weight on the end. For example, in 1521 Ferdinand Magellan stopped his ships in the Pacific Ocean during the first circumnavigation of the globe and lowered such a line. After paying out all the line they had he was sure that the weight had not touched the bottom, but how deep was it? He knew the ocean was deeper than his 400 fathoms of rope (~730 m) – so he concluded that his ship was over the greatest depths in the oceans!

2.1.1 Bathymetry techniques

The development and use of a technique called sonar (SOund Navigation And Ranging) revolutionised the investigation of the oceans' depths. Originally developed for hunting submarines, in sonar a ship sends out a pulse of sound (a 'ping'), which is reflected by the target and the reflected sound wave is detected. It was soon realised that if they were 'loud' enough the underwater pings could detect the sea floor. If you measure the time it takes for a reflected ping to be heard and know the speed of sound in water, then you can derive the water depth. Using sonar, ships could record continuous depth measurements without stopping.

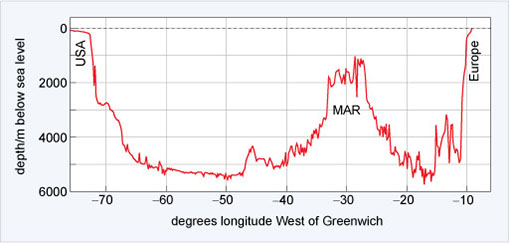

Figure 3 shows the bathymetry (i.e. depth measurement) across the North Atlantic Ocean along a latitude close to 39° N. At the point −30° W is the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR).The variability in depth is astonishing.

Figure 3

This line graph shows the change in ocean depth with longitude.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'degrees longitude West of Greenwich'. The axis scale begins at approximately −75° and ends at approximately −7°, but is marked at 20° intervals from −70° to −10°. There are vertical grid lines at the marked axis points.

The vertical axis is labelled 'depth/m below sea level' and is marked from 6000 m to 0 m, with 0 m at the top, in intervals of 2000 m. There are horizontal grid lines at intervals of 1000 m.

There is a black dashed line that runs horizontally at a depth of 0 m.

The depth data are represented by a solid red line which is labelled 'USA' at the left side and 'Europe' on the right side. There is also a label of 'MAR' at a peak in the line between −34° and −26°.

Moving right, from the left side (labelled 'USA'),

the ocean floor drops slowly at first and then rapidly to almost 3000 m (−70°) and then to near 5000 m (−60°),

the ocean floor then slowly drops further to approximately 5500 m before rising sharply to 4500 m (−45°),

this is the start of a gradual rise in the ocean floor with longitude followed by a sharp rise to 2000 m (−34°),

the ocean floor now stays above 2000 m, reaching as shallow as 1500 m, until it drops sharply back to 2500 m (−26°). This is the section labelled 'MAR'.

there is a steady drop in ocean floor back to 5500 m (−18°), then a section of sharp oscillations between 4500 m and 3500 m followed by a sharp rise to 0 m on the right side, labelled 'Europe'.

A further technological development in the late 20th century has enabled scientists to derive bathymetry using data from satellites orbiting the Earth at unprecedented resolution. But because of the way the satellites orbit the Earth the resolution of the data decreases towards the North and South Poles.

-

What will happen to the amount of detail that can be seen if the resolution of the data decreases?

-

It will also decrease.

Imagine what a height contour map of a mountain range would look like if you had only one average height in each 10 km square - many hills and valleys would simply disappear.

2.1.2 Bathymetric data online

Today some of the very best bathymetric data are freely available online, as you will see from Activity 1. Here, you will use Google Earth to investigate some of the features of the ocean floor and to navigate around using latitude and longitude.

Activity 1 The ocean depths

Part 1: Downloading and exploring a layered data file

Note: to complete every part of this activity, you will need to install the desktop version of Google Earth.

First watch Video 1, which demonstrates how to use Google Earth to look at the ocean. (You need to view this video in 'Full Screen' mode to see the details.)

Transcript: Video 1 Using Google Earth to look at the ocean.

Question 1

Using Google Earth find out the water depth at ~47° 34′ N, 7° 33′ 30″ W.

Answer

The most straightforward way is to type 47 34 N 7 34 W in the 'Search' box, then use your mouse and the latitude and longitude information on the bottom right to move your cursor to the correct point and so find the water depth at 47°34′ N, 7° 33′ 30″ W.

The water depth is approximately 1103 m.

Question 2

By moving your pointer, find out the approximate water depth off the coast of France and the depth of the darker (and so deeper) region to the west.

Answer

The water depth off the west coast of France is approximately 120 m and the depth in the dark blue region to the west is ~4600 m.

The light blue region is called the continental shelf and the deeper region is called the abyssal plain. The area between these two regions is the continental slope.

Task 2

Now download the Activity 1 data file to your computer and open it in the desktop version of Google Earth. Video 2 demonstrates how to use Google Earth with a file containing information in layers.

Instructions for downloading and opening the data file

Note: the file for this activity may download as a '.zip' file. If so, you will need to change the file extension to '.kmz' in order to open it easily in Google Earth. You can do this selecting the 'Save as' option when you download the file and changing the extension so that the file name ends in '.kmz' (i.e. 's206_1_activity_1.kmz'), then saving the file to your computer.

You may find that double-clicking on your saved data file automatically causes Google Earth to open. However, if this does not happen, you can open the file manually from the 'File' menu in Google Earth by clicking on 'Open…' and then using the resulting dialogue box to navigate to where you saved the data file, selecting it, and clicking 'Open'.

Transcript: Video 2 Using Google Earth with a file containing information in layers.

Having watched the video, now answer the question below.

Question 3

Open the Google Earth layer 'Depth Section across the continental slope'. This yellow line represents a depth transect across the continental shelf, the continental slope and the abyssal plain.

Using the technique demonstrated in Video 2, what is the average depth and slope of the continental shelf, the abyssal plain and the continental slope? Also record the length of the section you highlighted.

Answer

The average depth and slope of the continental shelf, abyssal plain and the length of the transect length over which the average is generated is shown in Table 1.

| Location | Average depth/m | Average slope/° | Transect length/km |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continental shelf | ~159 | 0.2 | 50 |

| Abyssal plain | ~4727 | 0.2 and 1.0 | 27 |

| Continental slope | ~2467 | 0.4 and -7.5 | 49 |

From your measurements you should be able to see that both the continental shelf and the abyssal plain are astonishingly flat. A slope of between 0.2° and -0.2° over 50 km is flatter than anything one would observe on land. And despite the continental slope looking steep, the average slope is only -7.5°. Features look abrupt and steep in Google Earth and in the way relative heights in charts are represented, when in fact they are not.

Task 3

Now watch Video 3 from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which shows some of the features of the sea floor using the same data you are using in Google Earth.

Part 2: Examining other features

Exploring ridges and trenches

Now watch Video 4 which demonstrates how to measure some of the other layers in the Google Earth file you have downloaded.

Transcript: Video 4 Demonstration on how to use layers with Google Earth.

The extremely large mid-ocean ridge and the trenches that you saw in Video 3 are part of the tectonic plate system of the planet. Using the Google Earth layers, explore some of the features you saw in Video 3: the mid-ocean ridge, and the sections across the Marianas Trench (the deepest known location), the Scotia Sea Trench (a more typical ocean trench) and the section shown in Figure 3. You should investigate and note the depths, gradients and general features you observe.

At divergent plate boundaries, tectonic plates are moving apart and new sea floor is being created in undersea volcanic eruptions. In convergent boundaries sea floor is being destroyed.

Question 4

Which sort of tectonic boundary are the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the Marianas Trench and the Scotia Sea Trench?

Answer

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a divergent boundary whereas the Marianas and the Scotia Sea Trenches are on convergent boundaries.

Exploring undersea vents

One of the most exciting discoveries in marine geology of recent years was the discovery of hydrothermal vents, where very hot water escapes from the Earth's crust into the oceans. If you click in the open box next to 'vents_InteRidge_2011_all.kml', all of the undersea vents known up to 2011 will be displayed on your map. The different coloured symbols indicate whether the vent has been directly or indirectly observed, and whether it is active or not.

Question 5

Are the vents typically found on divergent or convergent boundaries?

Answer

Overlaying the vent locations on the tectonic boundaries shows that the vents are typically found on divergent boundaries.

Task 4

To get an idea of the physical environment of a deep-sea vent, now watch Video 5 from the BBC series Planet Earth, and answer the questions that follow.

Transcript: Video 5 Physical environment of a deep-sea vent.

Question 6

Why is the water leaving the vents like billowing black smoke?

Answer

It is extremely hot and the water contains a chemical cocktail. The sulfides in the water solidify into chimneys and are presumably colouring the water black.

Question 7

How is life able to survive around the deep-sea vents?

Answer

A particular type of bacterium can use the chemicals in the hot water, and this in turn is eaten by shrimps and other animals.

Question 8

What are the fastest-growing marine invertebrates?

Answer

Giant tube worms are the fastest-growing invertebrates.

Question 9

Why do the animals on a deep-sea vent lead a tenuous existence?

Answer

Each community is unique and vents can start and stop rapidly. When they stop, the inhabitants will die.

Exploring Arctic gateways

For the final part of this activity, click in the open box next to the file called 'Arctic Gateways'. This file contains two transects: 'The Bering Strait' and 'The Greenland-Iceland-Scotland Gap'.

Question 10

Looking at the bathymetry across the two transects, which has the deepest depths from the Arctic to the rest of the global ocean? Is it the transect between the Pacific and the Arctic Ocean or the transect between the North Atlantic and the Arctic Ocean?

Answer

The deepest depths are between the North Atlantic and the Arctic Ocean along the Greenland to Scotland transect. Here water depths are in one region > 1000 m. The shallowest depths are between the Pacific and the Arctic Ocean across the Bering Strait, and water depths are only ~ 50 m.

You will see later in the course that the difference in maximum depths between the two ocean basins is critical for the circulation of the global oceans.

2.2 Summary of Section 2

- Typical features of the oceanic sea floor include the continental shelf, abyssal plains and mid-ocean ridges.

- Deep-sea vents provide a unique habitat far from the energy of the Sun.

- The deep passages to the northern seas are only in the Atlantic Ocean and they are relatively shallow.

3 Seawater

The presence of dissolved salts radically changes the physical properties of water.

In this section you will look at some of these properties and the typical vertical distribution of salinity and temperature throughout the oceans.

3.1 Salt in the oceans

The saltiness in seawater is due to a mixture of many different ionic constituents. If you boiled away 1 kg of seawater in a pan you would find, on average, 34.482 g of solid material left. (You would probably end up with less salt as some ionic constituents would form gases.) Almost 99.95% of the total mass of this solid material is made up of the constituents listed in Table 2.

| Ion | % by mass of 34.482 g | Weight/g kg−1 |

|---|---|---|

| Chloride Cl− | 55.04 | 18.980 |

| Sulfate SO42− | 7.68 | 2.649 |

| Hydrogen carbonate, HCO3− | 0.41 | 0.140 |

| Bromide, Br− | 0.19 | 0.065 |

| Borate, H2BO3− | 0.07 | 0.026 |

| Fluoride, F− | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| Sodium, Na+ | 30.61 | 10.556 |

| Magnesium, Mg2+ | 3.69 | 1.272 |

| Calcium, Ca2+ | 1.16 | 0.400 |

| Potassium, K+ | 1.10 | 0.380 |

| Strontium, Sr2+ | 0.04 | 0.013 |

Quantitative analysis of the salt content in different oceans shows that although the total amount of dissolved salt varies from place to place, the major elements are always present in the same relative proportions. This amazing fact is called the principle of constancy of composition.

-

If the ratio of the amounts of the ions of K+ to Cl− in the Atlantic Ocean was 0.02, what would be the ratio of the two ions in the Pacific Ocean?

-

The ratio of the K+ to Cl− ions would be exactly the same at 0.02, because of the constancy of composition of seawater.

The dissolved salts mean that seawater conducts electricity well and conductivity is directly proportional to the salt content. Salinity is defined by comparing the conductivity of a water sample with that of a reference sample of 'standard seawater'. Since salinity is effectively describing a ratio it has no units - but it can be labelled 'practical salinity units' (PSU). In older books and on some websites, you may find salinity expressed in parts per thousand (abbreviated to ppt or given the symbol ‰). While this is technically incorrect, for all practical purposes they are equivalent. The salt composition in the global oceans has not significantly varied in the last 108 years. The residence time of seawater is ~4000 years. So the processes that add salt to the ocean and the processes that remove salt from the ocean must be in balance.

The salinity of seawater of average ocean density is 34.482.

3.2 The density of fresh water and seawater

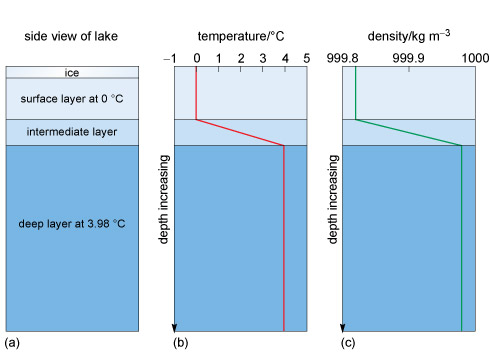

Fresh water and seawater have very different physical properties. Imagine a freshwater lake in winter. As the air temperature falls the temperature of the water at the surface decreases and its density changes (Figure 4).

Figure 4

This is a line graph showing the change in density with temperature.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'temperature/°C' and is marked from 0 °C to 10 °C in intervals of 1°.

The vertical axis is labelled 'density of freshwater/kg m−3' and is marked from 999.6 kg m−3 to 1000.0 kg m−3 in intervals of 0.1 kg m−3.

There are horizontal and vertical gridlines at the marked axes points.

The density data are represented by a solid green line.

The pattern in the line is an asymmetric inverted 'U' shape.

The density is approximately 999.86 kg m−3 at 0° and then increases steadily to a maximum of almost 1000.0 kg m−3 at approximately 4°.

The density then decreases steadily to 999.73 at 10°.

-

What is the temperature at maximum density?

-

The maximum density is at ~4 °C (Figure 4). At both lower and higher temperatures than this the water is less dense.

While it is hard to see on the scale in Figure 4, the maximum density is at 3.98 °C. As a lake cools to this temperature in winter the surface waters will sink through convection and warmer water rises to the surface. With continued cooling this warmer surface water also becomes dense and sinks. As the surface water is being cooled the lake will become stratified. That is, the density will increase with depth to 1000 kg m−3, and the deep water will have a temperature of 3.98 °C. Imagine the convection continuing until all the water has reached 3.98 °C.

-

What will happen to the water in the lake when all the water is cooled below to 3.98 °C?

-

The water at the surface of the lake will cool and become less dense. This means that it will not sink away from the surface. So the lake will end up with a cool surface layer with warmer, denser water beneath.

Eventually the surface layer of water will be cooled to the freezing point (0 °C) and ice will form on the surface. At this point the temperature and density of the water will have a structure like that shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

This is a series of 3 diagrams that show the change in temperature and density with depth in a lake and within designated layers within the depth profile of the lake.

Figure (a) is on the far left and is labelled 'side view of lake'

This diagram shows the depth profile of the lake along with 4 identified layers to this profile.

The top layer is labelled 'ice', is the narrowest of the 4 layers and is shaded very pale blue.

The layer below this is labelled 'surface layer at 0 °C', is the third narrowest of the 4 layers and shaded very pale blue.

The layer below that is labelled 'intermediate layer', is the second narrowest of the 4 layers and is shaded in slightly darker shade of blue than the top 2 layers.

The layer at the bottom is labelled 'deep layer at 3.98 °C', is the widest of the layers and is shaded in the darker blue.

Figure (b), in the middle, presents temperature data as a line graph. It has the same colour and layering as Figure (a), except there are no labels and the top 2 layers (ice and surface layer at 0 °C) have been merged into one layer.

The horizontal axis is located at the top of the figure and is labelled 'temperature/°C' and is marked from −1 °C to 5 °C in intervals of 1 °C.

The vertical axis is labelled 'depth increasing' with no quantitative markings. There is black directional arrow head pointing downward at the lower end of the axis.

There is a red line indicating the temperature. The red line runs vertically, at a temperature of 0 °C from the top of the graph to the top of the intermediate layer. In the intermediate layer the red line shows an linear increase in temperature with depth from 0 °C to approximately 4 °C. The red line then runs vertically down through the bottom layer at approximately 4 °C.

Figure (c), on the right presents density data as a line graph. It has the same colour and layering as Figure (a), except there are no labels and the top 2 layers (ice and surface layer at 0 °C) have been merged into one layer.

The horizontal axis is located at the top of the figure and is labelled 'density/kg m−3' and is marked from 999.8 kg m−3 to 1000 kg m−3 in intervals of 0.1 kg m−3.

The vertical axis is labelled 'depth increasing' with no quantitative markings. There is black directional arrow head pointing downward at the lower end of the axis.

There is a green line indicating the density. The green line shows the same pattern of change as the red temperature line in Figure (b). The density starts at approximately 999.82 kg m−3 at the surface and remains at that value down to the top of the intermediate layer. In the intermediate layer the green line shows a linear increase in density with depth from 999.82 kg m−3 to approximately 999.98 kg m−3. The green line them runs vertically down through the bottom layer at approximately 999.98 kg m−3.

Figures 5b and c show that the temperature and the density increase with depth from the surface to the bottom layer, where the temperature is 3.98 °C and density is at its maximum.

Let us think about this a little more.

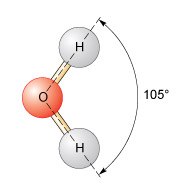

Usually when a liquid is heated the molecules acquire more energy and become more widely spaced, so in the same volume, the density decreases. In fresh water the opposite may happen, depending on the temperature. When fresh water at 3.97 °C (Figure 4) is cooled the density will decrease. You know from the lake (Figure 5) that ice (i.e. solid water) is less dense and floats. But cooling a liquid usually packs the molecules more closely, which increases the density. This means that below 3.98 °C cooling results in the water molecules spacing out and both the liquid and the solid water below this temperature expand. This is an amazing physical property and is why pipes burst and water in cracks shatters rocks in cold temperatures. The molecular structure of a water molecule is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6

This is a schematic diagram of a water molecule.

The oxygen atom is represented by a circle, shaded red and labelled 'O'.

The hydrogen atoms are represented by a circle, shaded grey and labelled 'H'.

1 oxygen atom is connected to 2 hydrogen atoms and the connection is shown by an narrow elongated rectangle shaded pale orange.

The water molecule has an 'L' shape with the oxygen atom at the corner and the 2 hydrogen atoms radiating out from this corner.

There is a dashed black line that radiates from the oxygen atom to each of the hydrogen atoms, along the connecting rectangle.

These dashed lines extend past the hydrogen atoms and they are then connected by a solid black line in the shape of an arc with directional arrow heads at either end.

The arc represents the angle of the 'L' shape or the angle between the two hydrogen atoms and is labelled '105°'.

In H2O, the oxygen and the hydrogen atoms share electrons, and the angle between the two hydrogen atoms is 105°. This results in a small net negative charge on the oxygen side of the molecule, and a small net positive charge on the hydrogen side. This is a polar structure in which molecules are weakly attracted to each other and form weak 'hydrogen bonds'. At low temperatures a more ordered packing of water molecules develops and the density is reduced. If the temperature is increased but is <3.98 °C, the hydrogen bonds break, but the molecules still pack together closely. Above 3.98 °C, the increase in internal energy means the molecules become more widely spaced and, following Figure 4, the density decreases.

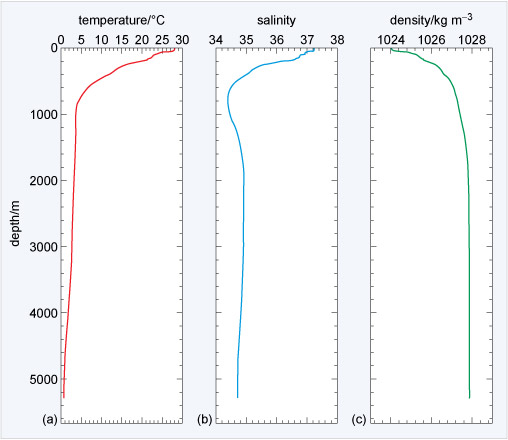

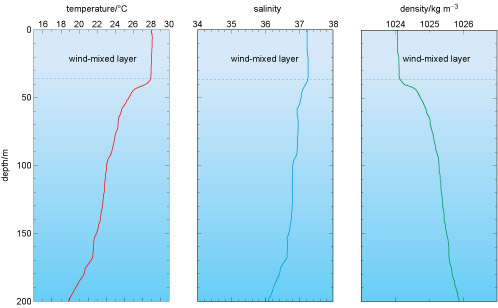

Seawater is saline and the salt affects the density. Figure 7 shows the vertical structure of the temperature, salinity, and density at latitude 20° S in the Atlantic Ocean over an abyssal plain almost 5300 m deep.

Figure 7

A series of three line graphs to show the change in temperature, salinity and density with depth in the Atlantic ocean.

All three graphs share the same vertical axis. The scale is the same for all three graphs and there are major and minor axis ticks on the left and right aides of each graph. However, the axis is only labelled and numbered on Figure (a) on the left. Here the vertical axis is labelled 'depth/m' and goes down from 0 m to 5300 m, with minor axis ticks at intervals of 200 m, but only the major axis ticks are numbered, from 0 m to 5000 m in intervals of 1000 m.

In all three graphs the horizontal axis is labelled and marked at the top of the graph, and the major and minor axis tick marks are also shown, unlabelled, at the bottom of the graph.

Figure (a), on the left, shows the temperature data with a red line.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'temperature/°C'. It is marked from 0 °C to 30 °C in intervals of 5 °C with unlabelled minor ticks at intervals of 1 °C.

The red line starts at 29 °C at the surface and temperature decreases rapidly to approximately 4 °C at 1000 m depth. From there the temperature drops more slowly as seen by an almost linearly change with depth to 1 °C at 5100 m.

Figure (b), in the middle, shows the salinity data with a blue line.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'salinity'. It is marked from 34 to 38 in intervals of 1 with unlabelled minor ticks at intervals of 0.2. No units are indicated.

The blue line starts at 37.2 at the surface and salinity decreases rapidly to approximately 34.2 at 800 m depth. From there the salinity increases slightly to 35 at a depth of 1800 m and then decreases slowly to 34.8 at 5100 m.

Figure (c ), on the right, shows the density data with a green line.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'density/kg m−3'. The axis scale is from range 1023.2 kg m−3to 1028.8 kg m−3 with unnumbered minor tick marks at intervals 0.4 kg m−3. The major tick marks are numbered from 1024 kg m−3 to 1028 kg m−3 in intervals of 2 kg m−3.

The green line starts at 1024 kg m−3 at the surface and density increases steadily with depth to approximately 1027.2 kg m−3 at 600 m depth. From there the density increases slowly to 1028 kg m−3 at 5100 m.

Figure 7a shows 28 °C temperature at the surface to below 1 °C at the sea floor. The variation in salinity in 7b clearly affects the temperature of maximum density shown in 7c. The seawater density ranges from 1024 to 1028 kg m−3, ~24-28 kg m−3 denser than fresh water (Figure 4), and density increases with depth and the water is stratified all the way to the sea floor (although >3 000 m depth there is only a small increase). Because seawater is typically 1024-1028 kg m−3 there is a density anomaly, σt (pronounced 'sigma t') given by:

where ρ is the density of water.

-

What is the range of σt for typical seawater?

-

The density anomaly for typical seawater is in the range 24-28 kg m−3.

Box 1 explains how the physical properties shown in Figure 7 are measured.

Box 1 Measuring the physical properties of the ocean

Much of our knowledge about how the oceans circulate is based on measuring the various parameters such as temperature and salinity from the surface to the sea floor. The water which makes up this range is called the water column. The most important instrument used by oceanographers is called a CTD (Figure 8), which measures the conductivity and temperature of the seawater and depth (pressure).

The photo shows the instrument sitting on the wooden deck of a ship. The deck is wet, so it's probably just been winched out of the water. The instrument is within a cylindrical frame about 2.5 metres high and 1.5 metres in diameter. The collection bottles are dark grey, about a metre long and thin, and lie within the top third of the instrument. There are about 20-25 of them arranged vertically in a concentric pattern.

Because pressure in the ocean is proportional to the weight of the water above, it is given by the hydrostatic equation:

where p is pressure, z is a change in depth and g is the acceleration due to gravity. The minus sign indicates that the vertical coordinate z (depth) is positive in an upwards direction. So by measuring pressure, Equation 2 can be arranged to get depth.

Other parameters can also be measured, such as sediment particle density, the amount of chlorophyll present (in algae), and so on. A CTD is lowered from a ship on a winch at a rate of ~60 m min−1. If the ocean is 5300 m deep, as in Figure 7, a round trip is 10 600 m and one profile can take almost three hours.

3.3 The surface properties of the oceans

The surface properties are the parts of the ocean that are most familiar to humans. They are also relatively straightforward to observe, and reveal a surprising amount about the underlying circulation.

The following sections explore briefly two of the fundamental properties of oceanic surface water.

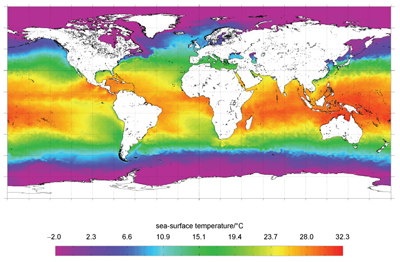

3.3.1 The surface temperature

The only significant source of energy heating the oceans is from the absorption of solar radiation arriving at the surface. The low albedo of water means that most solar radiation is absorbed to heat the surface - and generally, the greater the intensity of the incoming solar energy, the warmer the water (Figure 9).

Figure 9

This is a global map showing sea surface temperatures as indicated by range of colours.

There are evenly spaced horizontal and vertical gridlines that are unlabelled.

The land masses are shown in white and the ocean is shown in colour according to the surface temperature as indicated in the key.

The key is located underneath the map and consists of a horizontal band of colours.

The key is labelled 'sea surface temperature/°C' and is marked from −2.0 °C to 32.3 °C in intervals of 4.3 °C.

The colour scale begins with purple at the lowest temperature and then progresses through dark blue (2.3 °C) to pale blue and into green (15.1 °C). The shade of green gets darker and then fades into yellow above 24 °C and then into orange and red at the highest temperature.

The pattern on the map shows relatively even horizontal banding.

A similar pattern of banding is presented from the Antarctic to the Equator as is seen from the Arctic to the Equator. There is a band of purple colour at very high latitudes fading through blue, green and orange, with the orange and red colours along a central band along the Equator and in the tropics.

Noticeable deviations from the background pattern are fingers of green extending further north along the east coast of South America and Africa, as well as an extension of the green and blue colouration up the north Atlantic coast over Europe and an extension of the purple and dark blue down the northeast coast of Canada.

In general, the sea-surface temperature (SST) is colder at high latitudes and warmer in the mid-latitude and equatorial regions, but there are exceptions. For example, the North Atlantic coast of Africa has an SST of ~15 °C compared with >28 °C at the same latitude on the other side of the Atlantic. Note the light blue along the northwest European coast (see Figure 1), and the green 'tongue' of water extending up the west coast of South America. Clearly, there is more to the surface temperature distribution than simply incoming solar energy. The heat must be being redistributed.

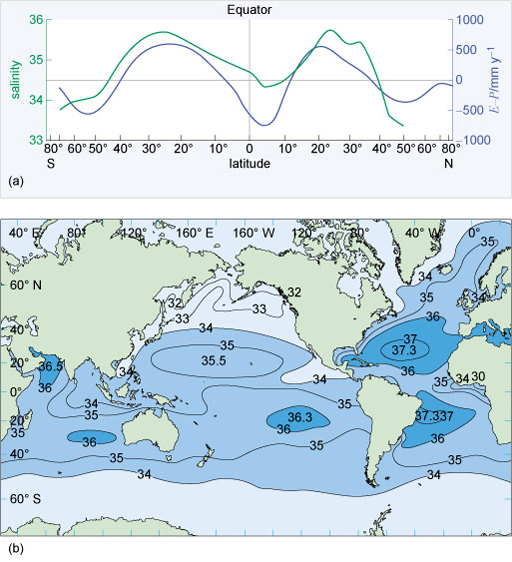

3.3.2 The surface salinity

Sea-surface salinity is determined by two competing processes: precipitation and evaporation. Precipitation (P) (including rain and river flow) reduces the salinity of the sea surface while evaporation (E) increases surface salinity by the removal of water. The (E-P) balance is shown in Figure 10 along with the resulting approximate global surface salinity distribution.

Figure 10

There are two parts to this figure that show the change in salinity and E-P with latitude; part (a) is a line graph (above) and part (b) is a contour map (below).

Part (a): The line graph shows the change in both salinity and E-P with latitude.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'latitude' and is marked from 80° S to 80° N in intervals of 10°. There is an axis tick for 70° but no number on both the N and S sides. The scale of the axis is not linear and the size of each 10° interval increases the closer it is to the Equator. There is a single vertical gridline at the centre of the axis, at latitude of 0°, and this is labelled 'Equator'.

The vertical axis has two scales indicated. The vertical axis on the left is labelled 'salinity' and is marked from 33 to 36 in intervals of 1. There are no units indicated. The vertical axis on the right is labelled 'E−P/mm y−1' and is marked from −1000 mm y−1 to 1000 mm y−1 in intervals of 500 mm y−1. There is a single horizontal gridline at the centre of the axis, at E−P = 0 mm y−1.

The salinity data are represented by a green line.

The E−P data are represented by a purple line.

Both lines follow a similar 'M' pattern with increasing and decreasing undulations.

The salinity line is low (33.8) at 70° S and steadily increases to a first peak of 35.6 near 25° S before falling again to 34.4 at approximately 3° N. There is another increase to 35.7 at 24° N and then a drop to 33.4 at 50° N.

The E−P line begins at approximately −100 mm y−1 at 70° S and then has an initial drop to −600 mm y−1 near 54° S before it rises steadily to its first peak of 500 mm y−1 near 25° S. This is followed by a steady decrease to −750 mm y−1 at 5° N and then an increase to a second peak of 500 mm y−1 at 20° N. The line then decreases to −400 mm y−1 at 50° N and rises to a minor peak of almost 0 mm y−1 at 70° N.

Part (b) shows a world map, centred on the Pacific Ocean, showing contours of equal levels of salinity and with increasing levels of salinity indicated by increasingly darker shades of blue.

The edges of the map are marked to show longitude and latitude with labels along the top and left sides.

The longitude is marked along the top edge, in intervals of 20°, with numbered marks at intervals of 40°, from 40° E to 0°.

The latitude is marked, along the left edge, from 60° S to 60° N in intervals of 20°.

Contour lines of equal salinity are shown in the oceans with labelled, solid black lines. The salinity levels for the contour lines ranges from 32 to 37 in intervals of 1.

There are also some labels for specific point value for salinity.

The contour bands are indicated by different shades of blue. There is no key, but the shading is as follows:

salinity less than 34 = very pale blue

salinity from 34 to 36 = pale blue

salinity greater than 36 = dark blue.

The general patterns shown by the map are;

very pale blue bands at high latitudes.

a band of pale blue from approximately 50° S to 40° N with a finger of pale blue extending very far north in the Atlantic over Northern Europe and Scandinavia.

The dark blue areas are confined to five patches in the following general areas:

Arabian Sea between Saudi Arabia and India,

an area in the Indian Ocean off the east coast of Australia,

an area in the South Pacific Ocean between Australia and South America,

a large portion of the South Atlantic Ocean from the South American coast (20° S to 40° S) and extending almost to the west coast of Africa,

and the largest area is located in the North Atlantic Ocean from the Gulf of Mexico across to northwest Africa and Spain (10° N to 40° N), and also includes the Mediterranean Sea.

A negative E-P value freshens the sea surface, and the shape of the purple line in Figure 10a is interesting. The 'M' shape between 60° S and 60° N shows positive peaks at ~25° S and 20° N due to decreased rainfall and high evaporation, while the trough is due to high rainfall and river inputs.

Figure 10b shows a striking difference between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans: the salinity in the Atlantic is much higher. In the Pacific Ocean, lines of equal salinity, called isohalines, tend to follow lines of latitude, but not in the Atlantic because of the ocean's circulation. Another example can be seen off the coast of Portugal where less saline waters extend southwards. Like the SST, the surface salinity is being redistributed.

3.4 The vertical distribution of properties

The properties of the ocean surface are changed by (E-P) and solar input but, as you have already seen in Figure 7, there are variations in these properties with depth.

-

How can surface changes be carried deeper into the ocean?

-

The energy can be transported downwards by the conduction of heat and diffusion of salt, and by being mixed up by the wind.

Both conduction and diffusion in the ocean are slow processes that can effectively be ignored. It is the effect of the wind on the surface of the ocean that dominates. Wind creates turbulence, thus mixing water to create a layer of almost constant temperature, salinity and density called the wind-mixed layer (Figure 11).

Figure 11

A series of three line graphs to show the change in temperature, salinity and density with depth in the Atlantic Ocean.

All three graphs share the same vertical axis. The scale is the same for all three graphs and there are major and minor axis ticks on all graphs. However, the axis is only labelled and numbered in the graph on the left. Here the vertical axis is labelled 'depth/m' and goes down from 0 m to 200 m, with minor axis ticks at intervals of 10 m, but only the major axis ticks are numbered, from 0 m to 200 m in intervals of 50 m.

In all three graphs the horizontal axis is labelled and marked at the top of the graph and the major and minor axis tick marks are also shown, unlabelled, at the bottom of the graph.

All three graphs show the same colouration. The graph is pale blue at the top with a gradual transition to dark blue at the bottom.

In all three graphs there is a horizontal dashed line at a depth of 38. The area above this line is called the 'wind-mixed layer'.

The graph on the left shows the temperature data with a red line.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'temperature/°C'. It is marked from 16 °C to 30 °C in intervals of 2 °C with unlabelled minor ticks at intervals of 1 °C.

The red line starts at 28 °C at the surface and the temperature remains constant in the wind-mixed layer, with the red line running almost vertically to a depth of 38 m. Below this depth there is an initial sharp decrease in temperature to 26 °C at a depth of 45 m and then a gradual decrease to 19 °C at a depth of 200 m.

The graph in the middle shows the salinity data with a blue line.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'salinity'. It is marked from 34 to 38 in intervals of 1 with unlabelled minor ticks at intervals of 0.2. No units are indicated.

The blue line starts at 37.2 at the surface and salinity remains constant in the wind-mixed layer, with the blue line running almost vertically to a depth of 38 m. From there the salinity decreases gradually to approximately 36 at a depth of 200 m.

The graph on the right shows the density data with a green line.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'density/kg m−3' and is marked from 1024 kg m−3 to 1026 kg m−3 in intervals of 1 kg m−3.

The green line starts at 1024 kg m−3 at the surface and density remains constant in the wind-mixed layer, with the green line running almost vertically to a depth of 38 m. Below this depth there is an initial sharp increase in density to 1024.5 kg m−3 at 45 m, then a gradual increase in density to 1025.9 kg m−3 at a depth of 200 m.

Figure 11a shows the surface-mixed layer is approximately 38 m thick, with a temperature of ~28 °C, salinity of 37.2, and density of 1024 kg m−3. In locations where the winds are particularly strong, the mixed layer can be up to 200 m thick. Beneath the mixed layer temperature and salinity both decrease down to ~800 m depth (Figure 7). This region of rapidly decreasing temperature is called the permanent thermocline; below this, the water temperature decreases to <1 °C at the sea floor. While the temperature and salinity vary with depth, the density - which is a function of both - continues to increase.

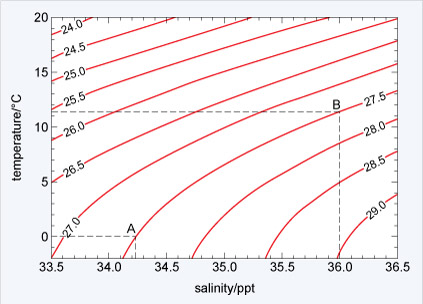

Figure 12 shows a plot of temperature against salinity. The x-axis shows salinity and the y-axis is temperature. The density anomaly σt of seawater is shown by the contours (red lines), which are labelled in kg m−3.

Figure 12

This is a graph of salinity against temperature showing 11 density anomalies as contour lines.

The horizontal axis is labelled 'salinity/ppt' and is marked from 33.5 ppt to 36.5 ppt in intervals of 0.5 ppt, with unmarked axis tick marks at intervals of 0.1 ppt.

The vertical axis is labelled 'temperature/°C' and the scale of the axis is from −2 °C to 20 °C with minor axis tick marks at intervals of 1 °C. The major axis tick marks are numbered from 0 °C to 20 °C in intervals of 5 °C.

The major and minor axes tick marks are repeated, unnumbered, along the top and right side of the graph.

Eleven density anomalies are presented with red contour lines on the graph.

Each contour line is labelled with the density ranging from 24.0 to 29.0 in intervals of 0.5. No units are indicated on the graph, but given in text as kg m−3.

The red lines show a regular diagonal banding pattern with the lines running from lower left to upper right of the graph.

The line representing the lowest density is located in the upper left of the graph and density increases toward the lower right of the graph, with an increase in the distance between each successive line as you move from top left to bottom right.

There are two points marked on the graph, labelled 'A' and 'B', and both of these points lie on the 27.5 kg m−3 density line.

Each of these points is connected to the horizontal and vertical axes by a dashed black line.

The values for each point are as follows:

Point A: salinity = 34.23 ppt, temperature = 0 °C

Point B: salinity = 36.0 ppt, temperature = 11.4 °C

Figure 12 has two labelled points: A has a temperature of 0 °C and salinity of 34.23; point B has a temperature of 11.4 °C and salinity of 36.0. But you can see that both points lie on top of the 27.5 kg m−3 σt contour. Despite a very different temperature and salinity they have the same density anomaly. One final, very important point is that Figure 12 shows that the gradient of the density anomaly lines is not constant. If you look at point A, keeping salinity constant but increasing the temperature to +5 °C will decrease the density anomaly to approximately the 27.1 kg m−3 σt contour - a change of 0.4 kg m−3 (27.5-27.1). At point B, keeping the salinity constant but increasing the temperature by +5 °C to 16.4 °C would decrease the density anomaly to approximately the 25.9 kg m−3 σt contour - a change of 1.6 kg m−3 (27.5-25.9). This non-linear response is also clear if you keep temperature constant and vary salinity, and while there is a simple equation to calculate density in fresh water, the equivalent for saline water is very complicated.

-

What is the density anomaly of seawater with a temperature of 15 °C and a salinity of 35.0?

-

Using Figure 12 the density anomaly of seawater can be determined as σt = 26.0 kg m−3.

3.5 The water properties along the Atlantic Ocean

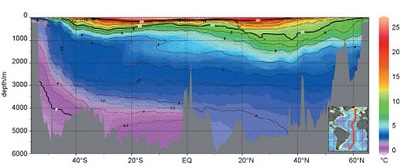

So far, you have looked at single profiles in one location. Figure 13 shows a line of CTD measurements called a hydrographic section. It shows the temperature and salinity distribution along the length of the Atlantic Ocean.

Figure 13

This is a vertical profile of the Atlantic Ocean showing contours of temperature with depth and latitude.

There is a small inset map in the lower right corner. This map is centred on the Atlantic Ocean and spans all latitudes. There is a solid red line running more or less north-south through the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

The horizontal axis of the main profile represents latitude, but is unlabelled. The axis scale goes from approximately 25° S to 65° N. There are tick marks at intervals of 10°, but numbered tick marks only at 20° intervals from 40° S to 60° N. The latitude of 0° is labelled as 'EQ'.

The vertical axis is labelled 'depth/m'. There are tick marks at intervals of 500 m but numbered only at intervals of 1000 m, from 0 m to 6000 m, with 0 m at the top of the axis.

There are horizontal and vertical gridlines at the numbered axes markers.

Along the bottom of the profile is a grey-coloured area, representing the ocean floor. The depth of the ocean floor starts shallow at 25° S and drops rapidly to below 5000 m at 30° S. It then undulates sharply up and down around the 5000 m depth with peaks at 40° S, EQ, 40° N and then it rises again to near surface at 66° N.

Contours of equal temperature are shown by labelled dashed or solid lines, ranging from 0 °C to 25 °C in intervals of 0.5 °C. The labels are black and very small. The contour lines for temperatures of 0 °C, 10 °C and 20 °C are bold and the labels are white.

The temperature is also indicated by colour coding and this is indicated by the vertical colour key bar to the right of the profile. The key bar is labelled '°C' and is marked from 0 °C at the bottom to 25 °C at the top in intervals of 5 °C. The colour of the bar changes from purple at the bottom (low temperature) through blue, green, yellow, orange, red and then to pale red and orange again at the top (high temperature).

The general pattern of the profile shows a narrow band of red/orange colour at the surface indicating high temperatures and then a steady decrease in temperature with increasing depth.

The warmer temperatures extend further down between 20° N and 60° N as evidenced by the bulge of the green colour down to depths of almost 2000 m in this latitude.

There is a distinct band of purple at depth from EQ to 25° S and this band of very low temperatures follows the ocean floor to the surface at 25° S. The spread of this band of very low temperature stops abruptly at the peak of ocean floor at EQ where the ocean floor rises sharply to 2000 m.

Figure 13 includes data from >120 CTDs and is created by plotting the latitude of each CTD station as the x-axis (which is over 11 000 km long), the y-axis as the depth measurements and colours representing equal temperatures and salinities measured at the CTD stations.

In Figure 13 the black lines of equal temperature - called isotherms - are superimposed on the colours and 0 °C, 10 °C and 20 °C are bold lines with white numbers. The spiky grey shaded region at the bottom of the plot is the sea floor along the section similar to that shown in Figure 3. The red line on the inset map shows the location of the section.

In the upper 1000 m the range of temperatures is very large (from blue to bright red) and the temperature can change as much as 20 °C. The isotherms are a squashed 'W' shape and are generally shallow at high latitudes above 40° N and 40° S, at their deepest points at about 30° N and 30° S, and shallow again at the Equator. Below 1000 m to the sea floor the temperature change is relatively small (4-5 °C). The isotherms at these depths have a 'U' shape across the Atlantic Ocean, rising towards the poles and deepest around the Equator. The mauve region in the south which contains the 0 °C water is close to the surface at 50° S. This is very cold water from the Antarctic that is descending and spreading throughout the deep ocean to be stopped by the seamounts of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

-

Is there ice in the deep ocean close to Antarctica?

-

No, there is no ice at this depth. Just as in fresh water, the ice would float because of the molecular structure of H2O. The salt in the seawater has lowered the freezing point of the water below 0 °C.

-

Based on what you have already learned, think of reasons why very cold water formed in the Arctic does not spread out through the deep ocean.

-

When exploring with Google Earth you found that the gateways from the Arctic to the rest of the global ocean are relatively shallow. The densest cold Arctic water is not able to enter the rest of the global ocean.

Finally, Figure 13 shows that at the Equator the temperature between the surface and the sea floor varies over a wide range - almost 30 °C. In higher latitudes the temperature range between the surface and the sea floor is very much reduced, for example at 52° S the range is only ~3.5 °C. Solar radiation is mostly responsible for heating the surface of the ocean, and the lack of solar radiation in the high-latitude regions is responsible for cooling the surface. Waters of different temperature are then spread throughout the oceans because colder water is denser and sinks beneath the warmer waters.

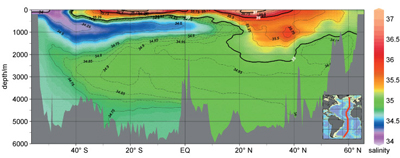

The salinity distribution in Figure 14 is more complicated. It is almost as though a clockwise circulation is wrapping the colours up. The very low-salinity, mauve-coloured water at the surface at about 50° S sinks and extends north at ~900 m depth. This implies that the low-salinity water at about 800 m depth in the salinity profile in Figure 7 originates in the Antarctic. North of this blue 'tongue' of water, there is an orange-yellow patch of water between 20 and 40° N of salinity ~35.5. Lastly, note that in the South Atlantic water below 4000 m must be the most dense - denser than the fresher water from the north.

Figure 14

This is a vertical profile of the Atlantic Ocean showing contours of salinity with depth and latitude.

There is a small inset map in the lower right corner. This map is centred on the Atlantic Ocean and spans all latitudes. There is a solid red line running more or less north-south through the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

The horizontal axis of the main profile represents latitude, but is unlabelled. The axis scale goes from approximately 25° S to 65° N. There are tick marks at intervals of 10°, but numbered tick marks only at 20° intervals from 40° S to 60° N. The latitude of 0° is labelled as 'EQ'.

The vertical axis is labelled 'depth/m'. There are tick marks at intervals of 500 m but numbered only at intervals of 1000 m, from 0 m to 6000 m, with 0 m at the top of the axis.

There are horizontal and vertical gridlines at the numbered axes markers.

Along the bottom of the profile is a grey-coloured area, representing the ocean floor. The depth of the ocean floor starts shallow at 25° S and drops rapidly to below 5000 m at 30° S. It then undulates sharply up and down around the 5000 m depth with peaks at 40° S, EQ, 40° N and then it rises again to near surface at 66° N.

Contours of equal salinity are shown by labelled dashed or solid lines, ranging from 34 to 37 in intervals of 0.25. The labels are black and very small. The contour lines for salinities of 34, 35 and 36 are bold and the labels are white.

The salinity is also indicated by colour coding and this is indicated by the vertical colour key bar to the right of the profile. The key bar is labelled 'salinity' and is marked from 34 at the bottom to 37 at the top in intervals of 0.5. No units are indicated. The colour of the bar changes from purple at the bottom (low salinity) through blue, green, yellow, orange, red and then to pale red and orange again at the top (high salinity).

The general pattern of the profile shows the highest salinity along the surface and decreasing salinity with increasing depth.

Notable deviations from the general pattern are:

the narrow surface band of high salinity penetrates deeper into the ocean between 20° N and 40° N as evidenced by the bulge downwards of the orange-red colouration to depths of approximately 1500 m in these latitudes,

surface salinity is low between 25° S and 40° S with a finger of low salinity (blue) extending from 40° S to 10° N at a depth of 1000m, there is a band lower salinity (pale blue) along the ocean floor as it drops rapidly away from the surface at 15° S and as far north as the rise in the ocean floor at 40° S.

In Section 4 you will see that both Figures 13 and 14 show features which are a result of the circulation of the ocean.

3.6 Summary of Section 3

- The constancy of composition means that the ratio of many different dissolved salt ions in seawater is constant.

- Water has very unusual physical and chemical properties and the polar molecular structure means that in fresh water maximum density is not the freezing point. However, in seawater this is different and density is a non-linear function of temperature and salinity.

- Seawater is heated at the surface by solar radiation and the salinity of seawater is controlled by the balance between evaporation and precipitation, E-P.

4 Ocean currents

In Section 1 it was noted that ocean currents can affect regional climate and the global surface distribution of temperature and salinity. In this section the focus is on surface currents and the three-dimensional global ocean circulation. You will learn that what drives this complex three-dimensional system is ultimately due to the energy from the Sun.

4.1 The global surface circulation

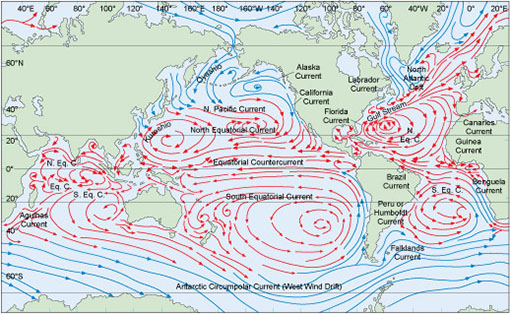

Unusual items washed up on beaches indicate the existence of ocean currents. For example, tree trunks are often washed up on the beaches of eastern Greenland - yet no trees have grown there for thousands of years. Figure 15 is a schematic diagram of the surface currents.

Figure 15

This is a world map, centred on the Pacific Ocean, showing ocean surface currents.

The edges of the map are marked to show longitude and latitude with labels along the top and left sides.

The longitude is marked along the top edge, in intervals of 20°, from 40° E through 180°, 160° W and then to 0° and ending with 20° E.

The latitude ranges from approximately 70° N to 70° S and is marked, along the left edge, from 60° S to 60° N in intervals of 20°.

There are horizontal lines across the entire map at latitudes of 0°, approximately 23° N and S, and approximately 66° N and S.

Surface ocean currents are shown by a series of red or blue lines and are labelled.

The following currents are identified in the Pacific Ocean:

Oyashio (blue lines): Flows from the north from the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait into the Bering Sea and then south along the northeast coast of Russia with a slight clockwise motion over the north of Japan.

Alaska current (blue lines): A clockwise current located in the Gulf of Alaska.

California Current (blue line): a straight current flowing south along the northwest coast of the United States.

North Equatorial Current (red lines): a small clockwise current located the mid-Pacific, just above the horizontal line at 23° N.

N. Pacific Current (red lines): A straight current, travelling west to east and flowing out from the Oyashio current into the North Equatorial Current.

Kuroshio (red lines): A clockwise current from 0° to 40° N along the western Pacific, bordered by Papua New Guinea to the south, the Philippines to the west and Japan to the north.

Equatorial Countercurrent (red lines): Large straight current travelling east to west along the Equator.

South Equatorial Current (red lines): A large counter clockwise current dominating the South Pacific and centred off the west coast of South America, from 0° to 55° S.

Peru or Humbolt Current (blue lines): This feeds cold water north from the Antarctic into the western edge of the South Equatorial Current along the west coast of South America.

The following currents are identified in the Indian Ocean:

N. Eq. C (red lines): east to west current along coastal India.

Eq. C. (red lines): tight clockwise currents in the Indian Ocean between 0° and 10° S.

S. Eq. C. (red lines): clockwise current centred off the east coast of Australia and then feeding out to the south of Australia and east into the main South Equatorial Current in the Pacific.

Agulhas Current (red lines): This current comes from the boundary of the S. Eq. C. and Eq. C. and travels southwest along Madagascar and then turns west and east at the south tip of Africa.

The following currents are identified in the Atlantic Ocean:

North Atlantic Drift (blue lines): this current travels south along the east coast of Greenland and then forms into a small clockwise current at the south tip of Greenland.

Labrador Current (blue lines): this current travels south along the west coast of Greenland and joins the North Atlantic Drift at the south tip of Greenland.

N. Eq. C. (red lines): a large clockwise current that is centred off the east coast of the United States. This spans the Atlantic to western Europe and northwestern Africa.

Gulf Stream (red lines): a straight current that travels from the southwest coast of the United States, from the northern edge of the N. Eq. C., northeast across the Atlantic and extends past the UK and along the Scandinavian coast.

Florida Current (red lines): a small current that feeds into the Gulf Stream from the Gulf of Mexico.

Canneries Current (red lines): part of the N. Eq. C that travels south along the west coast of northern Africa.

Guinea Current (red lines): a small system of currents feeding into the Gulf of Guinea off the central West African coast.

S. Eq. C. (red lines): a counter-clockwise current centred in the south Atlantic and spanning the ocean from South America to Africa.

Brazil Current (red lines): the western edge of the S. Eq. C that travels south along the coast of Brazil.

Benguela Current ( blue lines): this current feeds cold water from the Antarctic into the western edge of the S. Eq. C along the southwest coast of Africa.

Falklands Current (blue lines): a current of cold water from the Antarctic that travels north along the southeast coast of South America.

Circumpolar current:

Antarctic Circumpolar Current (West Wind Drift) (blue lines): This current travels around the globe, from west to east along the coast of Antarctic.

The fresher waters off the coast of Portugal mentioned in reference to Figure 10 are part of a vast clockwise surface circulation in the North Atlantic which consists of the Gulf Stream, the North Atlantic Current and the North Equatorial Current. This clockwise circulation is reflected in an anticlockwise pattern in the South Atlantic Ocean.

In the Pacific Ocean a similar clockwise pattern exists in the Northern Hemisphere and likewise an anticlockwise pattern in the Southern Hemisphere. The main difference between the two oceans is that the circulation in the Pacific Ocean is orientated more along lines of latitude than that in the Atlantic Ocean.

In the higher latitudes of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres the situation is different:

- the north has a series of smaller closed circulation

- the south has a continuous current around the Antarctic continent called the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

4.2 The effect of the wind on the oceans

The wind provides one of the main forces that move the surface of the oceans. When the wind moves across water, surface friction transfers energy from the wind to the water through wind stress. Wind stress has the Greek symbol τ (tau) and is proportional to the square of the wind speed, W:

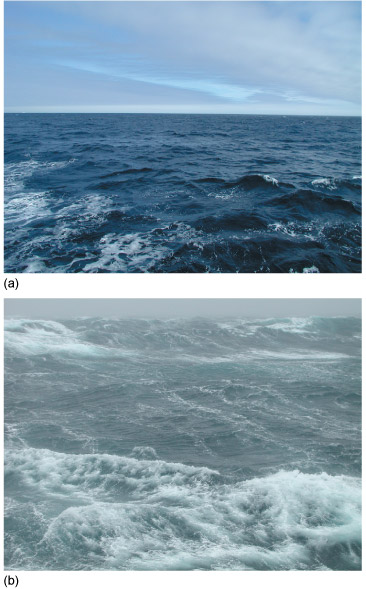

where c is the constant of proportionality. So if the wind speed increases from 1 m s−1 to 4 m s−1 then wind stress will increase by a factor of 16. This large jump in the wind stress happens because when the winds are weak, the surface of the ocean is relatively flat (Figure 16a) and there are few wave tops for the wind to push against. As energy is transferred from the wind to the ocean, the surface becomes rougher and 'stretched', so more of the surface is in contact with the wind (Figure 16b). The increased surface area leads to more energy being transferred to the ocean and larger surface waves.

(a) This photo shows a view out over the sea to the horizon. The sky is blue with some light grey cloud. The sea is dark blue and the surface is calm; only minor waves are visible and there is very little white water from breaking waves.

(b) This photo also shows a view out over the sea to the horizon. The sky is grey. The sea is dark grey and the surface is rough; numerous waves are visible and there is lots white water from breaking waves.

Once the surface of the water is moving, some of the wind's energy is transferred downwards into the water column through internal friction called eddy viscosity. The result is that momentum is transferred downwards and the mixed layers you saw in Figure 11 develop.

-

What effect will a rise in wind speed have on the thickness of the layer of well-mixed water?

-

It will increase because the surface waters will be mixed to a greater depth as more energy is supplied.

When the wind blows across the oceans, the surface waters are mixed and they start to move. But the direction of movement is not simply the same as the direction of the winds. The Earth is rotating and moving currents are affected by the Coriolis force, which arises from the rotation of the planet. Moving objects in the Northern Hemisphere are deflected to the right and those in the Southern Hemisphere are deflected to the left. The understanding of how the rotation of the planet affects moving ocean currents was developed through an experiment in the polar seas as described next.

4.3 Ekman drift

The obvious way to observe whether the oceans move in the direction of the winds is to follow a floating object. Early Arctic explorers noted that icebergs did not drift exactly in the direction of the winds, but 20-40° to the right of the wind direction. The Swedish mathematician Vagn Ekman developed a theory of wind-driven ocean currents to explain this observation. He started with the theoretical idea of an infinitely deep and wide ocean with no variations in density and imagined the ocean as a series of infinite horizontal layers.

A wind will move the surface through wind stress, but the surface is then acted upon by the Coriolis force and so is deflected to the right (in the Northern Hemisphere). This moving surface layer is also acted upon by friction with its lower surface - the eddy viscosity - and the layer underneath starts to move. But the transfer of momentum by friction is an inefficient process and the energy transferred is greatly reduced. This means that when the forces are in balance, the speed of the second layer down will be much less than that of the top layer. In the second layer the balance of forces means that it too is deflected to the right by the Coriolis force. This second layer is in contact with the deeper third layer and exactly the same processes happen there, and so on.

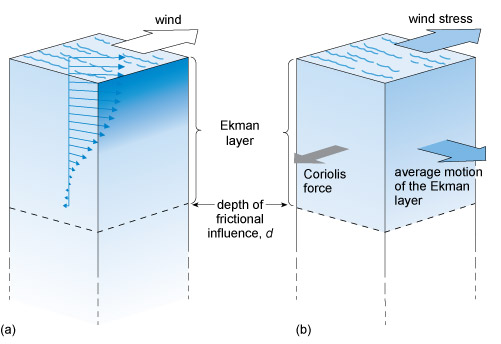

The result is that the energy transferred downwards significantly decreases with each layer and, more importantly, each layer will be deflected progressively to the right (in the Northern Hemisphere). The consequent rotation pattern in the upper layers of the ocean is called the Ekman spiral (Figure 17). The total depth of the frictional influence of the wind is called the Ekman layer.

Ekman found that, in his ideal ocean, the direction of the surface current will be approximately 45° to the right of the wind direction in the Northern Hemisphere, and 45° to the left of the wind direction in the Southern Hemisphere. A limitation of Ekman's theory is that the oceans are not infinitely wide and deep and that the eddy viscosity (that is, the friction between successive layers) varies with depth.

Figure 17

A pair of schematic diagrams depicting the Ekman layer and the forces involved in water movement.

Part (a), on the left, shows a square three-dimensional column of water, shaded pale blue, with a darker blue shading at the top of the right face. The three-dimensional perspective of the diagram such that one of the diagonals of the column is aligned with the page surface and the other diagonal is suggested as protruding from the page, therefore presenting a frontal view of two faces of the column.

The top of the column has undulating blue lines, suggesting the water surface.

There is a dashed black line across the column faces with approximately one third of the column below the line.

The dashed line is labelled 'depth of frictional influence, d'.

The volume above the dashed line is labelled 'Ekman layer'.

On the top of the column there is a broad white arrow that is labelled 'wind' and is pointing to the back and right.

There is a blue line that runs vertically through the Ekman layer, from the top of the column to the dashed line.

Radiating from this vertical line are a series of 20 blue arrows, evenly spaced along the length of the vertical line.

The arrow at the top of the vertical line is the longest of the series of arrows and is pointing from the central vertical line, diagonally along the plane of the paper, to the right.

Each successive arrow down the central vertical line is shorter in length than the one above and is rotated slightly clockwise.

Part (b) on the right is the same basic shaped three-dimensional square column. In this diagram only the Ekman layer is shaded blue and the volume under the dashed line is unshaded.

There are three arrows in this diagram:

On the top of the column is a broad arrow shaded pale blue and pointing back and to the right: this arrow is labelled 'wind stress'. On the front left face of the column is a narrower arrow, shaded grey and pointing out the front to the left at an angle of 180° from the wind stress arrow: this arrow is labelled 'Coriolis force'. On the front right face of the column is a broad arrow shaded blue and pointing to the front and left, at an angle of 90° clockwise from the wind stress arrow and 90° counter clockwise from the Coriolis force arrow: this arrow is labelled 'average motion of the Ekman layer'.

The most important point about Ekman's theory is that there is a layer of water (shown in Figure 17) at the surface (not necessarily the same thickness as the mixed layer) which is influenced by the wind and moves with a mean current called the Ekman drift over the depth of the Ekman layer. This is to the right of the wind direction in the Northern Hemisphere and the left in the Southern Hemisphere. Under typical conditions the depth of the Ekman drift is strongly influenced by the thickness of the mixed layer and is largely dependent on the time of year and wind speed, typically varying from tens of metres up to 200 m.

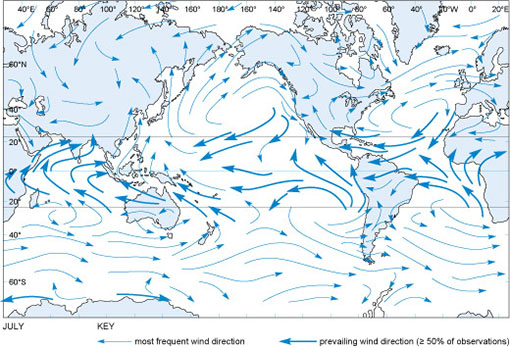

From the Ekman drift velocity and the depth over which it acts, the total transport of water due to the Ekman drift, called the Ekman transport, can be calculated. Armed with this basic theory of the wind-driven surface circulation, you can now investigate the effect of the global surface winds (Figure 18) on the oceans.

Figure 18

This is a world map, centred on the Pacific Ocean, showing the global surface wind pattern with blue arrows.

The edges of the map are marked to show longitude and latitude with labels along the top and left sides.

The longitude is marked along the top edge, in intervals of 20°, from 40° E through 180°, 160° W and then to 0° and ending with 20° E.

The latitude ranges from approximately 70° N to 70° S and is marked, along the left edge, from 60° S to 60° N in intervals of 20°.

There are horizontal lines across the entire map at latitudes of 0°, approximately 23° N and S, and approximately 66° N and S.

The map is labelled 'July' in the bottom left corner.

There are two styles of arrows in the map; the key below the map indicates what they represent;

a narrow blue arrow is labelled as 'most frequent wind direction'

a thick blue arrow is labelled as 'prevailing wind direction (greater than or equal to 50 per cent of observations)'.

Some general patterns in the map:

The thick arrows are mostly restricted to the zone between the horizontal lines at 23° N and 23° S and the direction of the arrows is mostly from east to west, with notable exceptions along the coast of Arabia and India where the direction is more to the north and northeast, and over southern Saharan Africa where the direction is from west to east.

High latitudes in the south show a regular west to east pattern of narrow arrows.

High latitudes in the north show clockwise patterns of narrow arrows over the North Atlantic and North Pacific Ocean, but more variable patterns of narrow arrows over the land masses.

Figure 18 compares well with the map of mean surface currents in Figure 15. Where surface currents join in continuous circulation patterns as in the North Atlantic, the effect of the Ekman drift is striking.

4.4 Divergence and convergence

Focusing on a closed surface wind circulation such as that in the North Atlantic Ocean (Figure 18), you can see a clockwise pattern repeated in the sea-surface current map in Figure 15. A large closed surface water circulation is called a gyre, and this particular one is the North Atlantic Gyre.

-

What will be the effect of Ekman drift in the centre of the North Atlantic Gyre?

-

There will be a slow movement of water into the centre of the gyre.

The drift of water into the centre of the gyre causes a surface convergence that pools water and actually raises the surface of the ocean by approximately a metre.

-

What will happen to the level of water in the centre of a gyre in the Northern Hemisphere where the circulation of the winds and surface currents is anticlockwise?

-

There will be a divergence. This will depress the surface of the ocean.

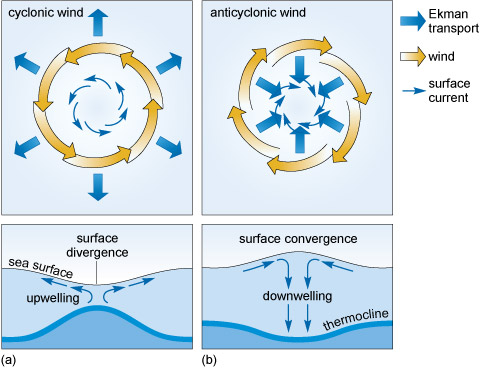

A clockwise circulation is called anticyclonic, and an anticlockwise one is cyclonic. Because of Ekman transport, an anticyclonic circulation causes a convergence of surface waters and a cyclonic circulation a divergence. Figure 19 shows that surface convergence and divergence have an effect beneath the surface.

Figure 19

A series of four schematic diagrams that are arranged as a column of two diagrams on the left, labelled '(a)', to show the effect of cyclonic winds, and a column of two diagrams on the right, labelled '(b)', to show the effect of anticyclonic winds on the ocean.

The two diagrams on the top are supported by a key, located in the top right, that shows the meaning of the arrows presented in these diagrams as follows:

a wide arrow shaded blue is labelled 'Ekman transport',

a wide arrow shaded white and fading into orange at the arrow head end is labelled 'wind',

a narrow blue line arrow is labelled 'surface current'.

The diagram on the top left is labelled 'cyclonic wind' and shows an inner circle of six curved blue line arrows pointing in a counter-clockwise direction, with an outer circle of six curved broad white/orange arrows pointing also in a counter-clockwise direction. There are six straight broad blue arrows located outside the outer circle and pointing in an outward direction, radiating away from the centre of the circle.

The diagram on the top right is labelled 'anticyclonic wind' and shows an inner circle of six curved blue line arrows pointing in a clockwise direction, with an outer circle of six curved broad white/orange arrows pointing also in a clockwise direction. There are six straight broad blue arrows, this time located between the white/orange arrows and the blue line arrows and pointing inwards toward the centre of the circle.

The lower two diagrams show a vertical profile through the upper layer of the ocean.

There are three layers in each diagram.

There is a narrow horizontal blue line in both diagrams that divides the top two layers. This line is labelled in the left diagram only as 'sea surface'.

There is a thick horizontal blue line in both diagrams that divides the bottom two layers but labelled in the right diagram only as 'thermocline'.

The diagram in the lower left shows a sea surface line which is concave and a thermocline line that is convex and a resultant thinner layer between the two in the middle. There are blue arrows pointing from the thermocline up to the sea surface and then horizontally along the underside of the sea surface line. These lines are labelled 'upwelling'.

The diagram in the lower right shows a sea surface line which is convex and a thermocline line that is concave and a resultant thicker layer between the two in the middle. There are blue arrows that point along the sea surface toward the middle and then down to the thermocline. These lines are labelled 'downwelling'.

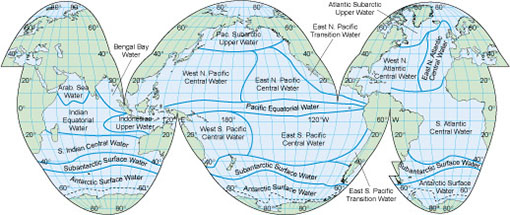

4.5 Surface water masses