Week 2: Learner-centred teaching

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Inclusive Teaching and Learning |

| Book: | Week 2: Learner-centred teaching |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 2 March 2026, 11:58 PM |

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Why is policy important?

- 3. Putting policy into practice

- 4. Implementing LCE

- 5. Learner-centred education: What does it mean to be learner-centred?

- 6. Where were you on the line?

- 7. Attitudes to learners

- 8. The justification for learner-centred education

- 9. The challenges of learner-centred education

- 10. The challenges of LCE

- 11. Quiz

- 12. Looking forward

1. Introduction

Last week you looked at why being included or excluded matters for everyone. You looked at some personal stories of exclusion and some local, national and international ideas on how to make education more inclusive.

This week you will focus on learner-centred education (LCE) as a policy response to calls for more inclusive teaching.

This week you will:

- consider the importance of policy in establishing inclusive practices

- examine what is meant by learner-centred education and how it works in practice

- engage with the ‘minimum criteria’ for learner-centredness

- consider the challenges of LCE in your context.

The focus is on what it means to be ‘learner-centred’ and why it is important. You will be introduced to tools to support you in analysing learning and teaching from a learner-centred perspective.

1.1. Activities for the week

|

Activity number |

Title |

Details |

Time |

|

2.1 |

Education policy |

Make a forum post about education policy in your country |

20 mins |

|

2.2 |

Putting policy into practice |

Watch a short video and reflect on how the activity described might link to policies |

20 mins |

|

2.3 |

Where are you on the line? |

Apply the ideas described in the text to your own context and reflect on the implications for practice |

30 mins |

|

2.4 |

Attitudes to learners |

Listen to a film clip and reflect on how to challenge the notion of ‘fixed intelligence’ |

15 mins |

|

2.5 |

The justification of LCE as a policy choice |

Read a section of an article and identify the most convincing arguments |

30 mins |

|

2.6 |

Minimum criteria for LCE |

Read a section of an article and interpret the minimum criteria for your practice |

30 mins |

|

2.7 |

LCE in practice |

Analyse teaching from an LCE perspective and identify key challenges |

30mins |

|

2.8 |

Challenges of implementing LCE |

Analyse the challenges that research into LCE reveals and reflect on your role in tackling these |

1 hour |

|

2.9 |

Week 2 quiz |

|

20 mins |

2. Why is policy important?

Setting out policies is how governments make things happen. The policies they develop will be based on an ideology, but also on international agreements such as the Sustainable Development goals, or the Paris Climate agreement.

In 1994 the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, 1994) set out a vision for inclusive education. The purpose of the statement was ‘to further the objective of Education for All by considering the fundamental policy shifts required to promote the approach of inclusive education, namely enabling schools to serve all children, particularly those with special educational needs’. piii

By setting out a vision in this way, policymakers are challenged to find a way of realising the vision in their country. Policies are important because they demonstrate a commitment from politicians to create circumstances in which the policies can be implemented. Inclusive teaching is enacted in classrooms, but teachers need support, resources and training, all requiring policies to be in place.

The policy response to the Salamanca Statement in many countries was a call for learner-centred education (LCE) and teaching which is more inclusive and supports the development of skills and values alongside knowledge.

Activity 2.1 Education policyAllow approximately 20 mins for this activity. In your context, what are the government’s priorities for Education? What does your government do to ensure that the system is inclusive? What is the impact of these policies and what else do you think they could do? Write a few sentences on the Week 2 forum (about 150 words), about your national context. Read and comment on at least two others. |

2.1. Optional further reading

UNESCO and other organisations have produced a great deal of material to support the implementation of inclusive education policies.

For example, you may like to download and read this resource:

Training tools for curriculum development: reaching out to all learners: a resource pack for supporting inclusive education, produced by UNESCO

UNESCO International Bureau of Education [12123]

2016

Section 1 is about reviewing national policies; section 2 is about developing an inclusive school and is more relevant to the second course in this series, and section 3 is about developing inclusive classrooms, reinforcing many of the ideas being introduced in this course.

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000243279

3. Putting policy into practice

The case study which follows is from the Global Monitoring Report, (UNESCO, 2020), (https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718) which focused on inclusion. The overall conclusion was that there is still a considerable way to go to ensure inclusive education for all. However, the report has numerous examples of inspiring practice from around the world. In Activity 2.2 you will watch a short video about a programme supporting inclusive education and reflect not only on the importance of policy, but also how attitudes towards supporting change have themselves changed and evolved.

Activity 2.2 Putting policy into practiceAllow approximately 20 mins for this activity. Case study Inclusion and Education: Voices from Malawi (2020) This short video describes a programme in Malawi designed to keep girls in school. Watch the video and make notes on the following:

|

4. Implementing LCE

This case study is an example of a practical programme to support inclusive education. In this case, policymakers can drive change by introducing laws that penalise parents who keep girls at home, and providing resources in the form of food, childcare and teacher training.

In the past, the policy in many countries was to create special schools for learners with particular needs. However, in recent years, whilst many excellent special schools still exist, there has been a move towards supporting students with special needs in mainstream schools, and to make these schools more inclusive.

Recognising the need to equip all young people for the future, this policy has been accompanied by a call for more learner-centred education and new school curricula which emphasise skills and values, alongside knowledge. The argument is that if educators focus on the needs of their learners, fewer will feel excluded and the quality of education will improve.

The implementation of policies based on learner-centred education (LCE) has proved to be challenging (Schweisfurth, 2011), and for the last 20 years researchers have been working to understand why this is. This week you will focus on LCE in more detail and be introduced to a set of flexible principles which can be adapted for different contexts. The principles help educators at all levels of the system enact the values and attitudes that underpin policy.

5. Learner-centred education: What does it mean to be learner-centred?

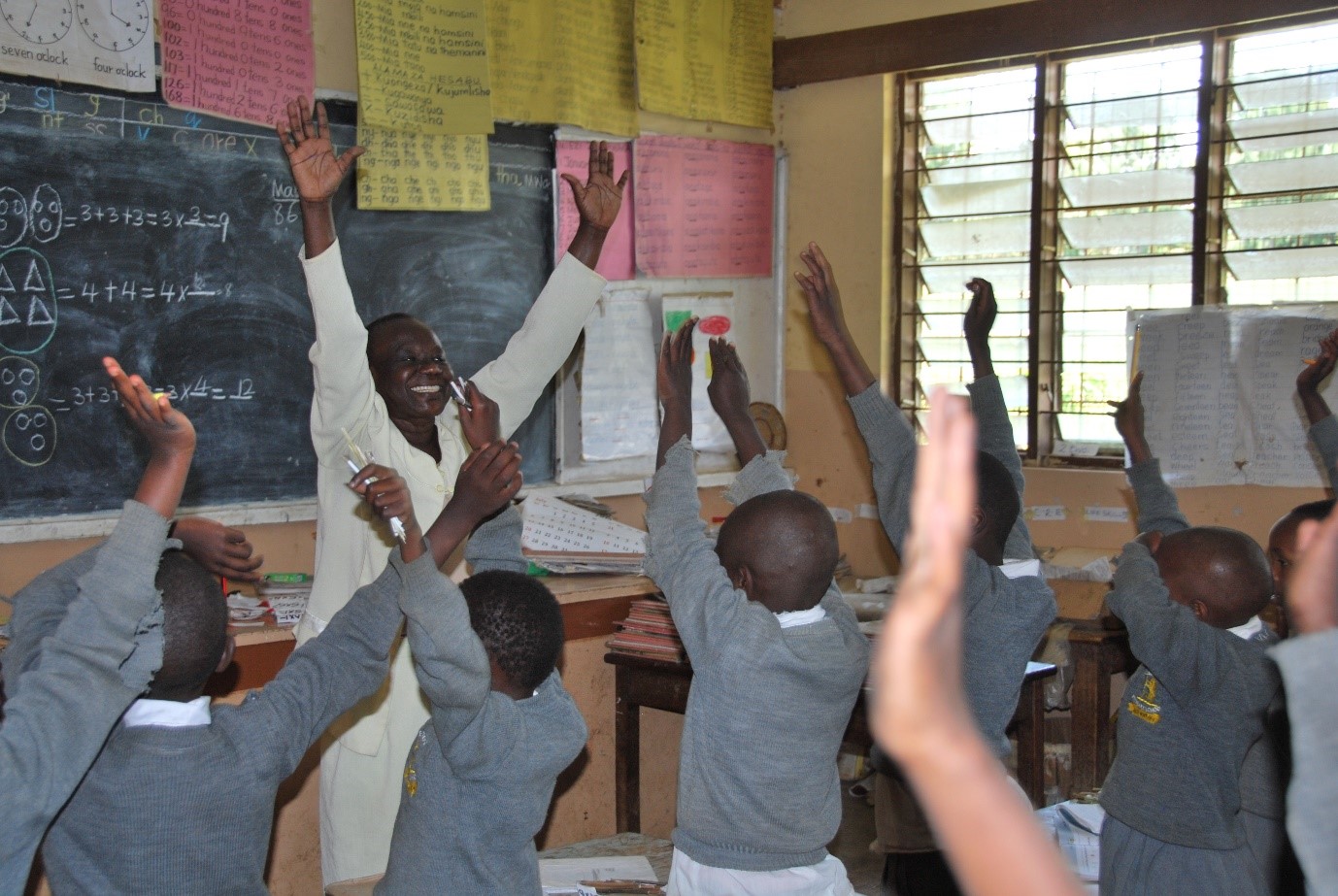

Learner-centred education is a policy response to calls for a more inclusive system. However, ‘the stories of unequivocal success in implementation are few and far between’ (Schweisfurth, 2011, p. 430). One possible reason for this is that learner-centred education is poorly understood. It is often interpreted as being a set of particular classroom approaches, such as group work, whereas in fact it is a set of attitudes and values. If teachers don’t embrace the attitudes and values which underpin the concept, then teaching approaches (such as group work), are unlikely to be successful.

5.1. Background to leaner-centred education

The concept of learner-centred education (LCE) is based on well-established theories of learning, starting with Socrates, who, in 400BC, proposed a vision for teaching based on questioning and inquiry rather than the transmission of information, and including Dewey (who championed experiential learning), Vygotsky and many others who highlight the importance of dialogue and collaboration to support learning.

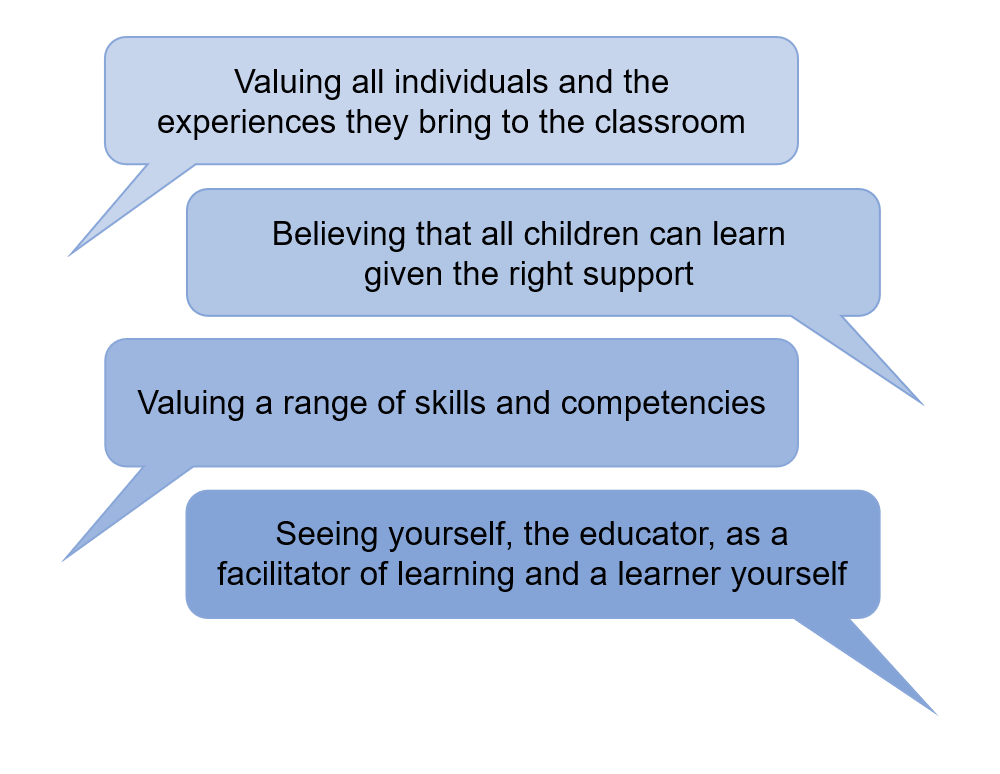

Learner-centered education is underpinned by a set of values and beliefs which are consistent with the aspirations of inclusive education. These include:

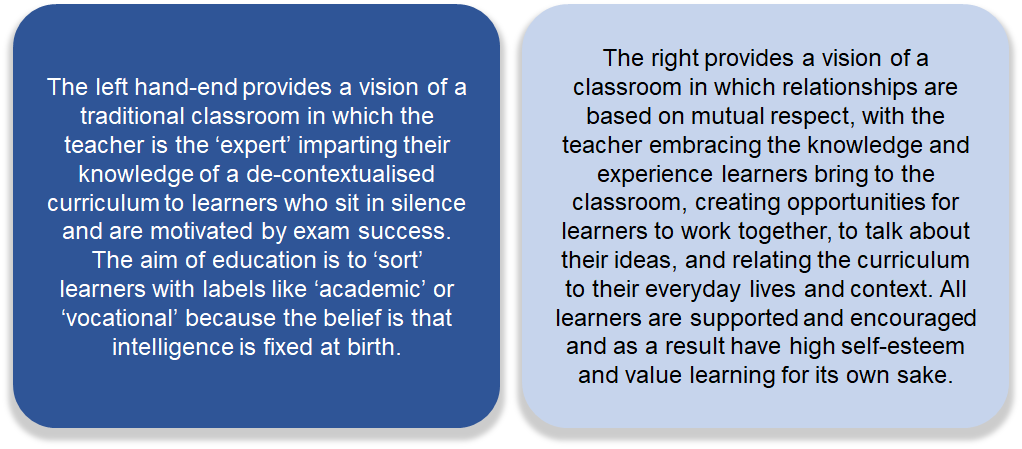

The reality of educational practice is that it is complex and nuanced. Aspects of practice are not ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, but are best conceptualised as a continuum (Schweisfurth, 2013), with educational practice being presented as ‘less learner-centred’ to ‘more learner-centred’:

less learner-centredmore learner-centred

|

Reflection point Think about your own experience of education. To what extent was it learner-centred? What evidence do you have that your teachers held (or did not hold) the values set out above? |

It is likely that a complex picture will have emerged – maybe you had authoritarian teachers, but were intrinsically motivated by an interest in and an obvious aptitude for a subject? Maybe you had teachers who treated you with respect and provided support with a curriculum which was largely irrelevant to your everyday life? Maybe it was decided that you had little aptitude for something in which you have since achieved highly? This complexity means that changing educational practice in the way set out in the policy statements above is a slow and individual process, which requires collaboration and support.

5.2. LCE as a continuum

Learner-centredness is about techniques (teaching approaches), attitudes and relationships. Evidence from around the world (Schweisfurth, 2011) shows that the techniques are unlikely to be effective if they are not accompanied by appropriate attitudes, values and relationships. It is possible to identify a variety of continua which could be helpful in thinking about LCE. In the next activity, you consider six continua, and reflect on where you sit on the imaginary line between two extremes and how you might move further to the right.

Extrinsic learner motivationintrinsic learner motivation

Teacher is the expert – main authorityteacher as facilitator of learning

Syllabus presented as decontextualisedSyllabus reflects lives of learners

Learning as an individual cognitive activitylearning as a social activity

Relationships based on authorityrelationships based on mutual respect

Intelligence is fixed at birtheveryone can learn given the right support

Activity 2.3 Where are you on the line?Allow approximately 30 mins for this activity. In this activity you will think about the continua set out above in the context of your own teaching, whether that be teaching students, student teachers or teachers. For each of the continua above, imagine a line joining the left to the right. Place yourself somewhere on that line. In your study notebook summarise why you have put yourself in that position. In what ways could your practice be considered ‘learner-centred’? In what areas would you like to move further to the right? How do you think you could do this within the constraints that are outside of your control? For example, a teacher who believes that intelligence is fixed at birth will give students who are considered to be less intelligent, basic tasks rather than challenge their learning by providing different types of support. |

6. Where were you on the line?

Many of you will recognise the vision on the left, as this probably represents your own experience of being at school, college or university. However, it is unlikely to be a simple as that.

It’s likely that in some cases you were over to the left, and in some over to the right. In order to realise the vision set out by UNESCO and others, in which all children have access to education and are fully included, then the attitudes and values on the right need to be reflected at all levels of the system.

Implementing policy involves everyone – educational leaders, teacher educators, school leaders and teachers – moving to the right. Implementation often fails because teachers are being asked to be facilitators of active learning, which involves all students and build relationships based on mutual respect but are treated in a manner more consistent with the attitudes on the left. Later this week and next you will consider how to make small steps along these continua and understand how this can lead to change.

7. Attitudes to learners

In all our conversations with educators, the importance of teachers’ attitudes to learners, especially those with special educational needs was highlighted. In the next activity you will hear Daniel talking about the challenge that prevailing attitudes can produce and you will focus more closely on the notions of ‘fixed intelligence’ vs ‘everyone can learn with the right support’.

Activity 2.4 Attitudes to learnersAllow approximately 15 mins for this activity.

View transcript / Download PDF Listen to Daniel talking about attitudes to inclusive teaching. As you listen, make notes on the following:

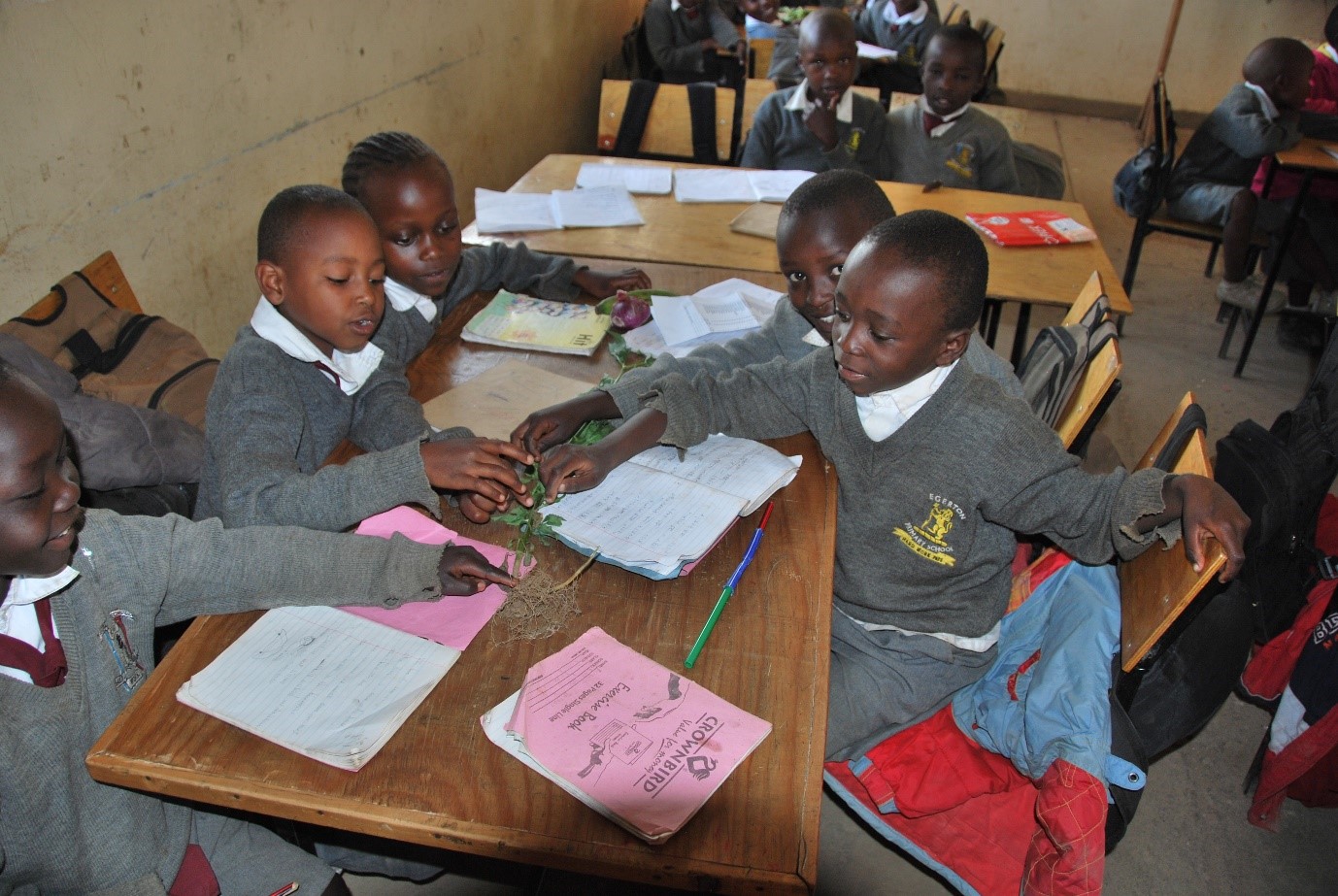

What practical steps do you think teachers can take to challenge the notion of ‘fixed intelligence’? For example – in Zambia, during school-based CPD teachers focused on organising more pair work and group work. Many commented that children whom they had previously labelled as ‘shy’ or ‘slow’ could do more than they realised in the safety of a smaller group. Setting tasks which are of an appropriate standard provides opportunities for praise and to raise self-esteem and ambition. Write a brief post on the Week 2 forum with one suggestion or example from your experience. Read and comment on two other posts. |

8. The justification for learner-centred education

The attitudes and values that underpin LCE are consistent with those that underpin inclusive education. This is why it is a popular policy choice. Now you have been introduced to the attitudes and values which underpin LCE, you will consider the justification for this policy choice as a way to support inclusive education and contribute to the vision set out in the Salamanca Statement. You are invited to access another one of the UNICEF Think Pieces (you encountered one last week on inclusive education).

The text is available here. The next two activities will consider different parts of this article.

Activity 2.5 The justification for LCE as a policy choiceAllow approximately 30 mins for this activity. On page 2, Schweisfurth describes 3 ‘justificatory narratives’ to support LCE as a policy choice (Why has LCE been promoted as policy and practice?). Write a sentence for each one in your study notebook, and place them in order of priority, with the most convincing argument at the top and the least convincing at the bottom. Which argument to you think is the most convincing and why? Share your choice on the Week 2 forum, along with a sentence to explain why you made that choice. |

Whichever ‘narrative’ you think justifies a policy of LCE, it is perhaps more helpful to reflect on real examples. In the example below, Kevin’s needs as a gifted learner were not met, with very unfortunate consequences.

|

Example from practice Kevin was a gifted student. He grasped new ideas very easily but was sometimes quite disruptive. Teachers found him difficult to manage, as he always seemed to be ahead of them with the lesson content. After some trouble in the library and an investigation, it was discovered that Kevin had a large number of books at home, which he had gradually stolen from the school library. He was immediately expelled from school. He moved to the city and used his intelligence to undertake criminal activity. He became very prosperous but was eventually killed as a result of his lifestyle. |

|

Reflection point Can you think of an alternative scenario, which could have happened if Kevin’s needs as a gifted student had been better accommodated? What could his teachers have done to prevent him becoming bored? |

Kevin was clearly a highly intelligent student and was bored at school. His teachers could have found out what he is interested in and used this information to challenge him intellectually. They could have posed interesting open questions for him to think about and research; provided newspaper or magazine articles on topical issues; and organised the classroom so that he could provide support for his peers. He could have become an asset in the school and taken on leadership roles. Challenging high achieving students is difficult and requires teachers to work together to help each other. It requires good subject knowledge and an ability to help students make connections between different topics and curriculum areas. Learner-centred education in practice

Having considered what LCE is, and why it is justified, in this section you will think about how learner-centred education manifests itself in learning and teaching.

In the article above, Schweisfurth lists seven principles to make current teacher-practice more learner-centred. She refers to these as ‘minimum criteria’. These principles can be applied to any level of the system and can be used as a tool to analyse teaching and learning.

These are:

- Lessons or training sessions which actively engage learners

- Mutual respect between teacher and learner (adult and child, or adult and adult)

- Lessons or training sessions which build on prior knowledge and understanding

- Opportunities for dialogue and considering open questions

- Learning that is relevant to children’s (or professionals’) lives

- A curriculum which supports the development of a range of skills

- Assessment which gives credit for a range of skills

One way to use these principles is to convert each principle into a question which could be used to reflect on teaching. In the next activity you will think about how to use these principles. After that you will apply them to your own teaching.

For example, principle one could be: what evidence is there that the students were actively engaged, actively involved and motivated to learn’? For a teacher educator or in-service co-ordinator, working with adults, the question would be ‘what evidence is there that teachers were engaged, actively involved and willing to ask questions?’

Activity 2.6 Minimum criteria for LCEAllow approximately 1 hour for this activity.

|

Activity 2.7 LCE in practiceAllow approximately 30 mins for this activity.

|

9. The challenges of learner-centred education

Despite the justificatory narratives you discussed in Activity 2.5 there is some critique of learner-centred education in the literature, suggesting that it is a Western world view which is being imposed on other cultures (Tabulawa, 2013).

The argument of this section has been that it is a set of attitudes and values that align with those of UNESCO and ‘The Rights of the Child’, rather than a specific prescription for how to teach. Teachers can embrace these beliefs in many different ways. Nevertheless, in some cultures these attitudes and values represent a significant shift from cultural norms. In some cultures children are taught not to express a view, or not to challenge someone older; young teachers are expected to follow the lead of those with more experience and people who are different in some way may be considered inferior or even cursed.

Activity 2.8 Challenges presented by LCEAllow approximately 1 hour for this activity. You will need the article: Is learner-centred education best practice? Consider the following questions and write your responses in your study notebook

Write a short forum post, identifying the challenge which is most relevant to your context and how it might be addressed. |

10. The challenges of LCE

Some people think that the metaphor of a ‘barrier’ to LCE is unhelpful. It implies something unmoveable, which is outside the control of individuals. It is perhaps more helpful to realise that there are underlying reasons that make the implementation of LCE challenging. If these can be tackled, the barriers will disappear. For example, building teacher capacity through training, accessing free resources and teacher preparation which models LCE are all doable (and will be considered in Week 4). It is tempting with large classes, for example, to use the excuse that I as an individual teacher cannot do anything about the size of my class. But with training and support, it is possible to improve your teaching practice to cope more effectively with large classes.

We are not, by any means, suggesting that exams, inspection regimes, large classes and a lack of resources don’t make life difficult – they do – but political will is needed to change these. In the meantime, there are things that individual teachers can do to make progress along the continua, even if they don’t quite reach the right-hand side.

|

Example from practice Denis attended a workshop. The participants were asked about the challenges that teachers face in developing active, participatory approaches to learning. The points made included:

The presenter suggested that these are things which they cannot do anything about and that there is a danger that they become excuses for not acting. She reworded the challenges:

The new mindset helped the group to refocus and as they discussed how to address these challenges the importance of collaboration and mutual support become obvious. |

|

Reflection point Consider the example above. In your notebook write down some of the skills that you feel you need to develop and how you might set about finding the support you need. |

10.1. Optional Activity

If you would like to consolidate your understanding of learner-centred education, you can listen to Michelle Schweisfurth presenting her ideas here:

11. Quiz

12. Looking forward

This week’s focus has been on learner-centred education as a possible means to inclusive education and as a popular policy response across the world. This perhaps because LCE is underpinned by the same attitudes and values as inclusive education: the belief that all children can learn given the right support; that learners come to learning with knowledge and experience that should be valued; and that a meaningful education values a range of skills, knowledge, values and competencies so learners are equipped to lead full lives.

You have been encouraged to think about LCE in terms of a set of continua and identified some ‘minimum criteria’ for learner-centred teaching which can be applied at all levels of the system. In Week 3 you will apply these minimum criteria to some of the inclusivity challenges identified in Week 1 in order to understand what LCE looks like in practice.

References

Schweisfurth, M. (2011). Learner-centred education in developing country contexts: from solution to problem? International Journal of Educational Development, 31(5), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.03.005

Schweisfurth, M. (2013). Learner-centred Education in International Perspective: whose pedagogy for whose development? Abingdon: Routledge.

Schweisfurth, M. (2019) Is learner-centred education ‘best practice’? YouTube video, Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U2JyTJkADmI&feature=youtu.be (Accessed 9 January 2021).

Schweisfurth, M.(2019) Is learner-centred education best practice? Chapter 9 in Chakera, S. Tao, S. (eds) The UNICEF Thinkspiece series: Innovative Thinking for Complex Educational Challenges in the SDG4 Era downloaded from https://www.unicef.org/esa/documents/education-think-piece-9-learner-centred-education Accessed on 12/01/2021

Tabulawa, R. (2013) ‘Teaching and learning in context: why pedagogical reforms fail in sub-Saharan Africa’, African Books Collective [Online]. Available at https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=xdD5GpVcoCYC&oi=fnd&pg=PR2&dq=Teaching+and+learning+in+context:+why+pedagogical+reforms+fail+in+sub-Saharan+Africa&ots=aZBprQRXko&sig=LkE8W9-KCv7mZBnOES1Kn3zw7zw#v=onepage&q=Teaching%20and%20learning%20in%20context%3A%20why%20pedagogical%20reforms%20fail%20in%20sub-Saharan%20Africa&f=false (Accessed 9 January 2021).

UNESCO (1994) The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education [Online]. Available at https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/Salamanca_Statement_1994.pdf (Accessed 9 January 2021).

UNESCO International Bureau of Education (2016) Training tools for curriculum development: reaching out to all learners: a resource pack for supporting inclusive education downloaded from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000243279. Accessed on 12/01/2021

UNESCO (2020) Global Monitoring Report [Online]. Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718 (Accessed 9 January 2021).

UNESCO GEM Report (2020) YouTube video, Inclusion and Education: Voices from Malawi [Online]. Available at https://youtu.be/w1rbGQXUbkU (Accessed 9 January)