Adapt for your context

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | TPD@Scale: Adapt for your context |

| Book: | Adapt for your context |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 26 February 2026, 10:18 AM |

4.1 Frameworks for planning TPD@Scale

In this activity you will work through two frameworks for planning TPD@Scale. If you are working in a group, see the facilitation notes.

The purpose of TPD@Scale programmes is to impact on educational quality by scaling improvements in classroom teaching.

Designing for scale and making local adaptations will take place in complex and dynamic settings, around the world.

To help you plan, implement and improve large scale programmes, scaling innovators and implementers have distilled their experiences and wisdom about scaling impact into four guiding principles.

Before you begin the next activity, watch a short presentation on these guiding principles. You were introduced to the principles in Course 3.

Disclaimer: This video has been uploaded for testing purposes only. Not for quotation or circulation.

4.2 TPD@Scale Compendium

1 hour

In Course 2 you read the . In the introduction to the Compendium you read:

To work effectively at a large scale, program designers need to consider how they manage available resources most effectively. It will not be possible to achieve the same results by merely replicating small-scale programs all over the country. For example, we know that coaching is an effective form of TPD but it is highly resource intensive and there are often insufficient numbers of skilled coaches across the whole country. The temptation might be to use structured materials instead of coaches. There are indeed situations where structured interactive learning materials can fully replace in-person interactions such as lectures or workshops but they are rarely able to provide sustained follow up or support social learning. Designers will need to plan instead how to effectively harness their most valuable resource – the teachers themselves, for peer mentoring and peer assessment, among others.

TPD programs delivered at scale need to make appropriate provisions available across large numbers of different settings that may be highly dispersed. To do so successfully, program designers need to consider variations in teachers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, existing working patterns and practices as well as variations in school culture, resources, and priorities. All these need to be understood and considered, from the initial design stage through to program implementation and evaluation using adaptive programming. The examples in this Compendium show how using ICTs can open up new possibilities in the design of large-scale TPD programs. Used in pedagogically sound ways, ICTs can facilitate the creation and delivery of high-quality, affordable TPD that is made available in different forms appropriate to the context and local needs.

However, successful scaled interventions not only manage issues of magnitude and variation; they should also be sustainable and empower local communities to own and sustain the reform in an equitable manner (Coburn, 2003). Many of the TPD@Scale programs described here ran for a fixed period, but through working holistically across the system, many of them disrupted existing models of large-scale TPD and prompted system shifts in TPD design, as in the Programa de Actualización Curricular Docente (PACD) program in Ecuador. This promises well for sustainability of the TPD@Scale approach and a shift from supply-driven provision to demand-initiated learning opportunities for professionals.

At the end of the Compendium, there is a set of questions, which we reproduce here.

Work through these questions on your own, with a colleague, or in a small group.

You can focus on one Compendium programme, if you are working through this course on your own.

If you are working through this course with colleagues, different people could look at different Compendium programmes, and then compare the programmes in a discussion.

|

These questions are intended to support individuals or small groups take forward ideas from the TPD@Scale Compendium into their own work. The Compendium describes 17 TPD programmes which use ICTs to facilitate access and participation in professional learning for large numbers of teachers or for teachers working in very challenging conditions.

Note down in your Personal Blog how you would adapt (or not) these features of your selected model or models:

In thinking about adaptation, we suggest you consider: a. Teachers’ professional learning priorities Note what data you need to make these adaptations to the model and how you might begin to collect this data. Which stakeholders will you need to involve in moving forward with TPD@Scale in your context? How might you engage them with the TPD@Scale ideas and approach? |

4.3 IDRC Scaling Playbook: Mapping the Scaling System

30 mins

In the previous activity, you thought of a TPD programme in your context that has potential for scaling, and you identified potential stakeholders.

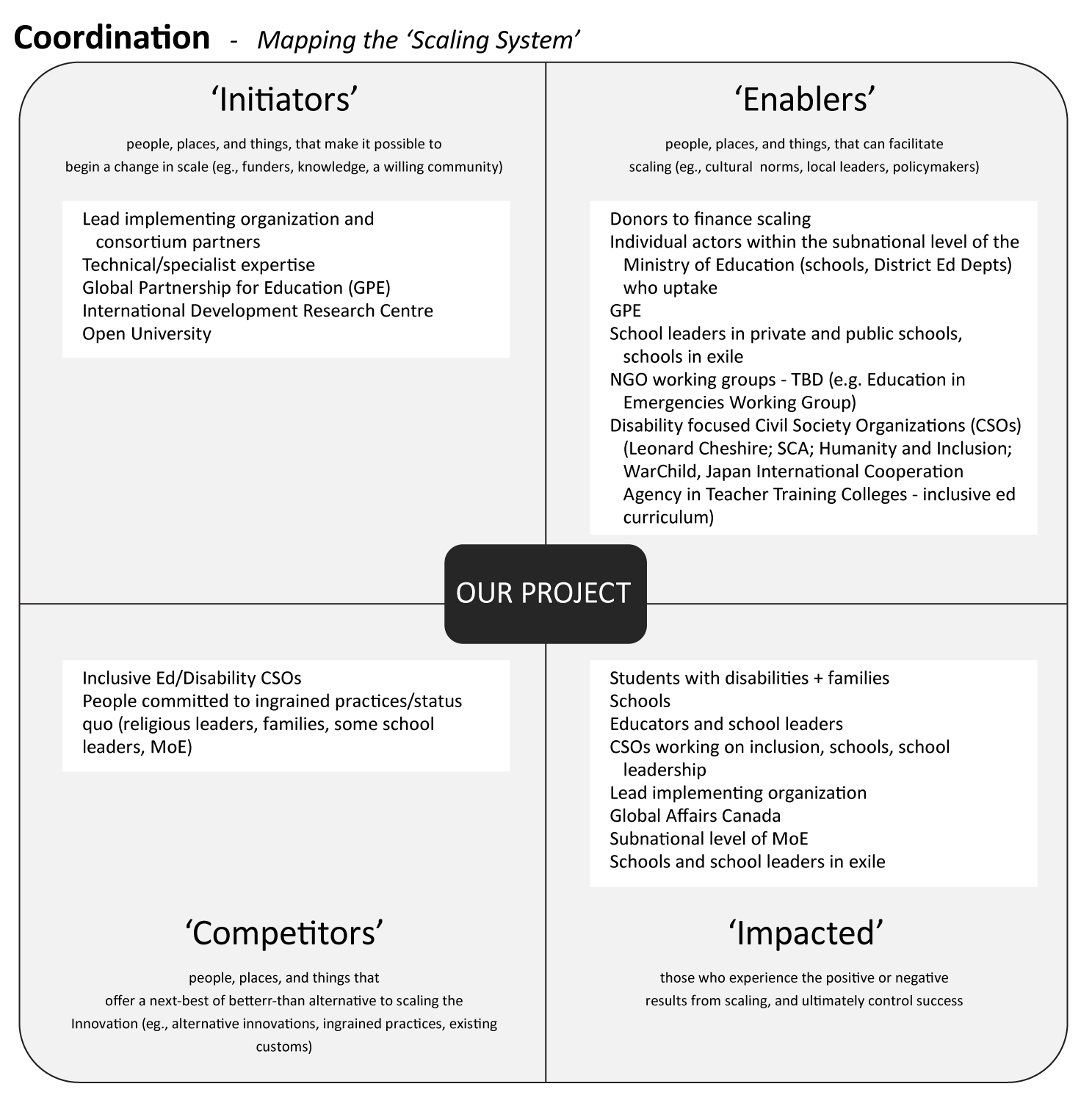

In Course 3 you read from the IDRC Scaling Playbook. On page 13 of the Playbook there is a worksheet called ‘Mapping the Scaling System’, which we reproduce here. This worksheet is useful to identify the range of stakeholders for scaling a TPD programme:

- Initiators – people, places and resources that would make it possible to begin a change in scale

- Enablers – people, places and resources that can facilitate scaling

- Competitors – people, places and resources that could prevent scaling, or offer a better alternative to scaling or a second-best option

- The Impacted – people who will experience positive or negative results from scaling

You can see an example of how these quadrants were used in practice, in a Global South country, to consider scaling a TPD programme. The programme here was to develop professional communities for school leaders with a focus on inclusion.

For the TPD programme you are considering for scale in your context, identify the

- Initiators

- Enablers

- Competitors

- Impacted

You can work on your own, with a colleague, or in a small group.

How difficult or easy was it to identify stakeholders and resources in each of the four quadrants?

Could you identify how teachers would be involved?

Record your ideas in your Personal Blog.

4.4 TPD@Scale and cost

1 hour

In Activity 4.1, one of the factors to consider in TPD@Scale is available finance.

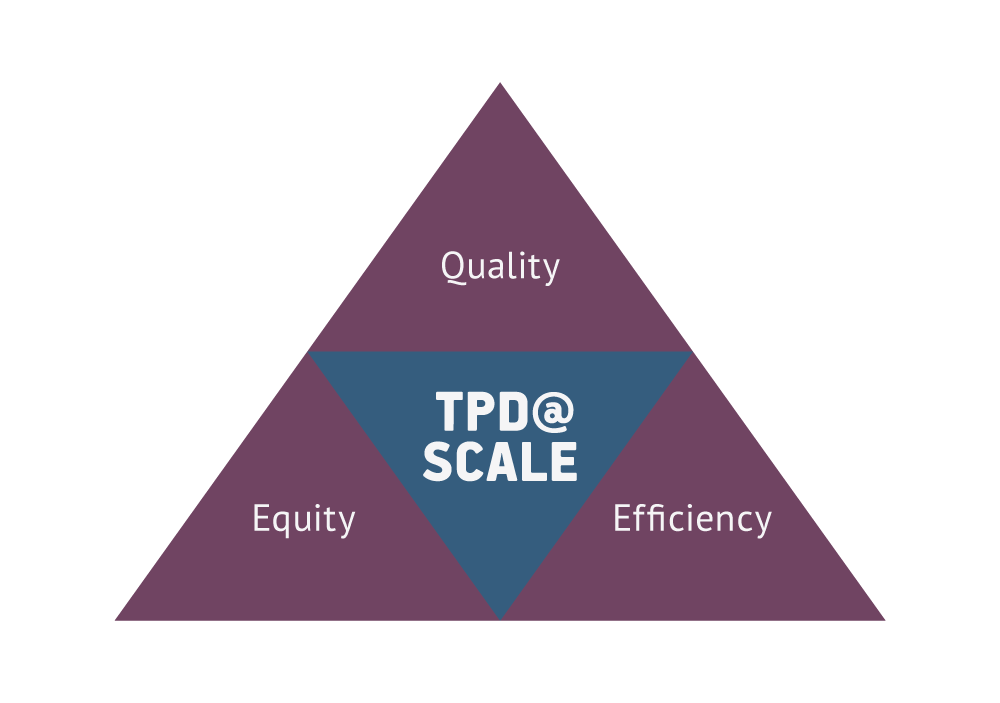

Efficiency is a foundational aspect in the TPD@Scale ‘triangle’ of Equity, Quality and Efficiency.

Consider these definitions:

- Cost-efficiency refers to the extent to which an institution or program maintains a particular level of production with fewer resources or increases the level of products or services it produces with a less than proportionate increase in the resources used. It thus refers to the ‘cheapness’ of educational provision.

- Cost-effectiveness refers to the extent to which an institution or program produces outputs (which are concrete and measurable) or outcomes (which may not always be measurable). It represents striking the optimal balance between cost, student [teacher] numbers and educational quality, a balance that changes according to educational context.

- Value for money refers to maximizing the impact of each unit of currency spent in order to develop a better understanding of costs and results so that choices of programs can be informed by evidence. This requires an understanding of the expected costs of a program and of its expected results.

Watch a short animation about balancing cost, quality and equity in planning TPD@Scale.

4.5 Cost-effective TPD@Scale examples

Read these TPD@Scale examples:

- from Brazil and South Africa, on how virtual coaching proved to be more cost-effective than onsite TPD;

- from the Philippines, on how blended learning led to improvements in the pedagogical and content knowledge of participating teachers.

Cost-effectiveness through Virtual Coaching in Brazil

|

A TPD intervention in Ceará state of Brazil had four components:

The treatment group of 156 schools in the randomized control trial had a 0.05 to 0.09 standard deviation higher performance on the state test and a 0.04 to 0.06 standard deviation higher performance on the national test. The expert coaching support provided through Skype kept the costs of the program at $2.40 per student and produced cost-effective impacts on learning compared to other rigorously evaluated TPD interventions that have cost data (Bruns et al., 2017). |

Cost-effectiveness through Virtual Coaching in South Africa

|

A randomized control trial which looked at different delivery models of structured learning programs in a pilot in South Africa, found that on-site coaching is more cost-effective (0.41 standard deviation increase in test scores per US$100) than centralized training workshops (0.23 standard deviation increase in test scores per US$100) and short coaching interventions (no significant impact). Given the challenge to scale on-site coaching, a variation of the program was tested using virtual coaching. The results after a year showed that this variation had the same effectiveness as on-site coaching in improving teacher instruction practice and the literacy outcomes of children. The cost of the virtual coaching was US$41 per learner, whereas the on-site model cost US$48 per learner (Kotze et al., 2019). |

Cost-effectiveness through Blended Learning in the Philippines

|

In 2015, the Foundation for Information Technology Education and Development (FIT-ED) developed and piloted the Early Language, Literacy and Numeracy (ELLN) Digital for K-3 Teachers in the Philippines as an alternative to the Department of Education’s (DepEd’s) traditional cascade model (10-day face-to-face workshop). ELLN Digital uses a blended approach combining self-learning with classroom practice, co-learning with peers in a school-based professional learning community and offline, interactive, multimedia modules. Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles help to improve the design, impact, and sustainability of the program through communities of practice known as Learning Action Cells (LACs). The pilot, which aimed to develop a more cost-effective and sustainable approach to provide at scale in-service teacher training, included 240 primary schools and over 4,000 teachers. An evaluation of the pilot, which focused on literacy teaching, found that there were statistically significant improvements in the pedagogical and content knowledge of participating teachers, particularly those in rural schools. Whilst the evaluation did not review cost-effectiveness, in 2019, the program started to scale nationally with a plan to reach over 250,000 teachers in three years due to the success of the pilot and its outcomes compared to the DepEd’s traditional cascade model (Oakley et al., 2018). |

For a detailed look at TPD scaling and cost, see the in the Resources section.

See the Facilitation section for questions and considerations when designing, delivering, and evaluating TPD programs.

4.6 Draft your TPD@Scale model

1.5 hour

Now take your learning and your ideas further, by drafting a TPD@Scale model for your context.

The model or example that you propose can be from the Compendium, or a mixture of different examples from the Compendium, or it can be an idea of your own for a TPD@Scale model.

In the model that you draft, identify these aspects:

- Components that promote equity

- Components that promote quality

- Components that promote efficiency

- The ICT or ICTs for the model

- How teachers will be empowered to participate and interact

In Course 3 you began an analysis of your context for TPD@Scale. Thinking back to that course, for the draft model that you are developing here, perhaps referring back to what you wrote in your Personal Blog, can you identify

- Aspects that need to be adapted for different groups of teachers

- The purpose of the adaptation or adaptations

Record your draft TPD@Scale model in your Personal Blog.

Share your draft with a colleague and ask for their feedback.

If you are working with others in a group, draft the model together and discuss it.

In the final activity for this course, you will consider assessment of learning in TPD@Scale.

4.7 Assessment of learning at scale in TPD

30 mins

In this course, you have drafted a model for TPD@Scale in your context.

How would you reflect on your model and its adaptations, in order to understand its impact on teachers and teaching?

Some questions you might ask are:

- How will we learn about teachers’ activities and experiences?

- How would this knowledge inform programme improvement?

- What assessment will be most useful to teachers and why?

- How will assessment be designed and evaluated in relation to quality, (cost) efficiency and equity?

- How will the assessment design and tools provide relevant data for improvement?

Assessment in TPD@Scale is not a one-off exercise where teachers are evaluated or graded. In TPD@Scale, assessment is designed for programme learning: it is an ongoing process of reflection and adaptive actions for programme improvement.

Watch a short presentation on assessment in TPD@Scale.

After you watch, read the short descriptions of 'promising practices' in assessment of learning in TPD@Scale. There is still much to learn and develop in this area.

Promising practices in assessment of learning at scale in TPD

There are many different types of assessment of learning but, to date, there is little evidence of assessment of learning at scale in TPD.

These examples of promising practice highlight how assessment in large-scale TPD programmes is being attempted in Indonesia, Colombia, and India, using competency mapping approaches, open digital badges (like the badges you collect when you study the four TPD@Scale courses) and reflective videos, as part of their overall TPD frameworks.

You can learn more about different forms of assessment in the in the Resources section, from which these case studies are drawn:

|

Promising practice – A nationwide teacher assessment and competency mapping framework in Indonesia In 2012, Indonesia launched its Teacher Competency Tests (TCT) as part of its national teacher competency mapping process, with a teacher workforce of approx. 3 million. The TCT assesses the professional and pedagogic competence of teachers and uses both online/offline modalities (depending on local connectivity). In 2015, the TCT had reached approx. 2.7 million teachers. Its aims were: (1) to obtain information on the number of teachers who have reached the required level of professional and pedagogical competency; (2) to create a teacher competency map which informs the State’s provision of subsequent teacher education and training; and (3) to assess teacher performance and inform subsequent teacher-related policy. In terms of design, the TCT took the form of a 2-hour test with 60-100 multiple choice questions (with 4 options of answers for each question). The TCT in Indonesia is a key component in teacher career development. Once the test is completed and a competency profile created, this is used as guidance for the self-development of teachers as well as support through TPD. At regular intervals, the TCT is conducted again to assess progress. The new results of the TCT are then used as the basis for further guidance and teacher development. In 2016, the government launched a follow-up policy on TCT results through the Learners’ Teacher Competency Enhancement Program (LTCEP). The LTCEP is a learning activity for teachers through training in order to improve the ability and competence of teachers in performing professional duties. The TPD activities are aimed at developing teachers’ abilities, attitude, and skills with the view of impacting teacher performance and the teaching and learning process in classroom. TPD activities are offered via face to face training, online training or a combination of both depending on your competency profile and the intensity of support needed. Source: Mardapi & Herawan (2018) |

|

Promising practice - TPD pre- and post-Covid 19 using open digital badges, India More than ever, in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, the need to support teachers and teaching and learning is even greater. Of particular concern is how this can be done for all teachers, i.e. at scale. In this vein, the Government of India has been considering the use of open digital badges to support at scale TPD efforts. Open digital badges have received global recognition as a means for designing, recognising, rewarding and monitoring teachers’ professional learning. In many countries badges are little used in TPD at present, but workshops and pilot projects implemented by the Open University, UK (OU) and Tata Institute of Social Sciences, India (TISS) in Assam, India have demonstrated how digital badges can be used to support professional learning. Their research suggested that badges can offer small, short, standalone achievements to give status and recognition to teachers’ efforts; wide-ranging flexibility in what can be awarded, evidenced and assessed; clarity for teachers in terms of articulating a clear criteria of what the required standard is; scalability by providing a potential common digital currency for local, regional and national TPD systems; engagement by allowing teachers choice in which badges they pursue to support their professional learning trajectories and shareability by allowing teachers to share their achievements with others and thereby building confidence and self-esteem, enhancing community recognition as well as being a marker for individual teachers’ progress and future TPD planning. Source: Cross et al (2021) |

|

Promising practice - Reflective videos as teacher assessment, Computadores Para Educar, Colombia Computadores Para Educar (CPE) is a programme run by the Government of Colombia which promotes educational innovation through the access, use and adoption of technology in the country's schools. CPE offers ICT-mediated TPD through the provision of computers and internet to Colombian schools. TPD is also offered in partnership with local universities that have a presence in regions of operation. The programme provides differentiated pathways through the Ministry of Education (MoE) defined “Educational Innovation Route” which supports teachers to move from one level/module to the next through differentiated support and capacity building. In terms of teacher assessment, programme tutors administer an entry and exit ICT skills test for teachers. There are 4 knowledge tests at the end of each level/module of the diploma course which must be passed. The final product – the capstone assessment - is a video made by the teacher, in which the learning process across the 4 modules is documented. The video remains as evidence in the teacher-student's Personal Learning Environment (PLE). |

These examples demonstrate some promising approaches to assessment in large-scale ICT-mediated TPD. Such assessment is challenging, due to the sheer numbers of the teaching workforce, uneven distribution of human and technical resources, logistical challenges, financing, policy coherence and how it all relates to teacher motivation and career progression. Nevertheless, such reflective approaches to TPD design can move towards more effective at scale approaches.

For a detailed look at assessment, see the in the Resources section.

Congratulations! You have completed Course 4.

Take the short quiz to achieve your digital badge and Statement of Participation. Good luck!