Unit 3: Prevention

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Implementing Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector |

| Book: | Unit 3: Prevention |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 25 November 2025, 3:11 PM |

Introduction

In this third unit of the course looks at how to implement safeguarding procedures to prevent harm from occurring. This is important and requires planning and implementation across all aspects of programmes and operations.

Welcome to Unit 3, where we look at how to implement safeguarding procedures to prevent harm from occurring.

This component of the ‘safeguarding cycle’ is extremely important and requires concerted planning and consistent implementation across all aspects of programmes and operations.

In this unit we examine the theory behind what motivates perpetrators to commit sexual or other forms of misconduct. We will also look at why some groups of children and vulnerable adults are more at risk of harm than others, for example adolescent girls and children with disabilities.

We will take the offender as a focus, unpacking the employment cycle, policies, and expectation setting within an organisation (we will examine organisational culture in Unit 6).

Within these key topics we will look at how empowerment and inclusion of vulnerable groups are key elements to ensure programmes are designed to help prevent harm by enabling greater reporting and whistleblowing to deter potential perpetrators.

Finally, we will explore prevention in the era of digital communication and social media

3.1 The nature of power

Power is a vitally important concept in safeguarding. Sometimes it is obvious, sometimes it can be subtle and hidden. We explain the different forms that power can take and explore ways that challenge it to enhance prevention.

Why does ‘power’ matter?

If you were a learner on Course 1: Introduction to Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector, you will remember the discussion on power and the different forms power can take.

It was argued there that relations of power and privilege lie at the heart of the exploitation, abuse and harassment of those who are vulnerable. We need to understand the nature of power in order to see how, when it is misused, it can result in harm, and be in a better position to challenge it.

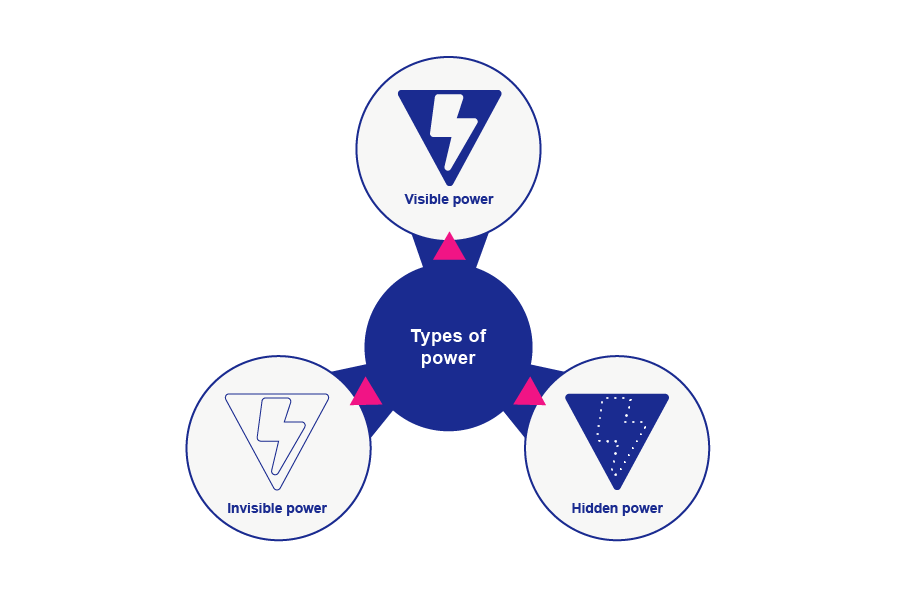

Power can be found in every relationship. The different forms of power are:

- Visible power – laws and rules that are put in place to control our behaviour.

- Invisible power – norms and societal values which may influence our behaviour.

- Hidden power – powerful people exerting their power over our behaviour.

As aid workers who may work with children and/or vulnerable communities and with each other, either directly or indirectly, we all have some form of invisible or hidden power over decisions being made on the lives of those who are less powerful.

We are in positions of power as we have access to resources which are needed by the communities that we serve. When used properly, this power can bring about good outcomes for all. When power is misused, however, it can result in harm, injury or even death.

To explain ‘power’, Gaventa developed a ‘Power Cube‘ as a framework for analysing the levels, spaces and forms of power, and their inter-relationship. It helps us visually map ourselves and situations, including other ‘actors’ and relationships, with an aim to mobilise social movements in order to advocate for change. (IDS, what have we learnt from the Power Cube?)

Power can be used in different ways:

- ‘Power over’ – this type of power is built on force, coercion, domination and control and motivates largely through fear. It is built on a belief that some people have power and some don’t.

- ‘Power with’ – is shared power that grows out of collaboration and relationships. It is built on respect, mutual support and collaborative decision making and action. ‘Power with’ can help build bridges within organisations or between differences (e.g., gender, culture, ethnicity). Rather than domination and control, ‘power with’ leads to collective action and the ability to act together.

- ‘Power to’ – refers to harnessing the potential of every person and all new possibilities in order to make a difference without using domination.

- ‘Power within’ – relates to a person’s sense of self-worth and self-knowledge. It includes an ability to recognise individual differences, but still respect them at the same time.

If you want to learn more about power, follow the links below:

- Power, Poverty & Inequality (PDF) IDS (2016)

- Power and making change happen (PDF) Carnegie Trust

- No Excuse for Abuse Interaction

Why we must address power

It should be acknowledged that, as adult aid workers, we do not like giving up the power that we have for various reasons.

Most of us enjoy being in control of situations, particularly when we think we are good people helping others less fortunate than us. Unfortunately, sometimes this paternalistic thinking means that we retain all power and control and are thereby prolonging the dependency of children and vulnerable adults. The lack of sharing of power can actually harm the people that we work with or serve.

As we explored in the previous section, we need to think of ways of moving from ‘power over’ to ‘power with’ to help prepare us to collaborate and promote the participation of those that we serve.

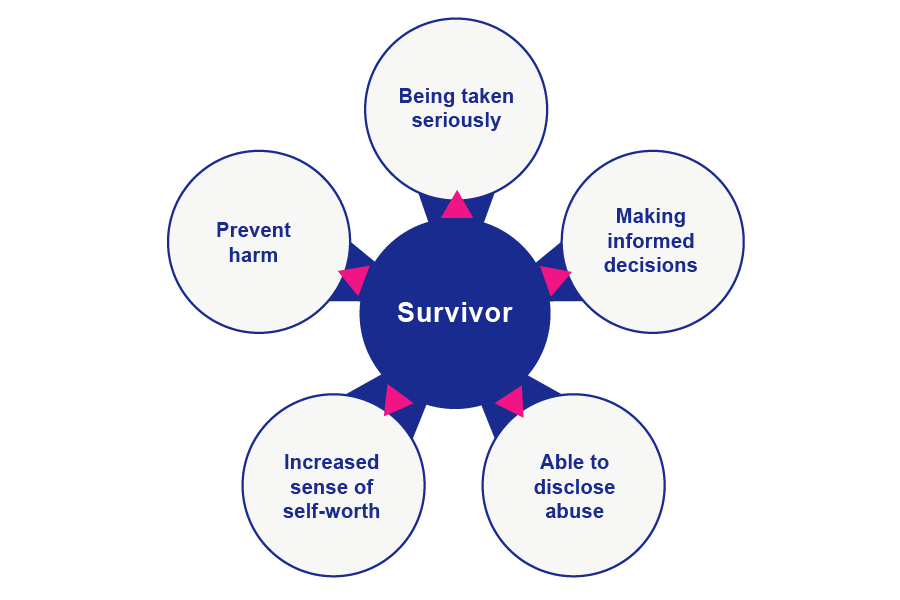

Adults and children have a right to be protected from all forms of harm and empowering them with this knowledge is important in terms of protecting them in their families and communities, as well as from organisations which work with them.

Organisations can do this by promoting the meaningful participation of children and vulnerable adults in decisions that affect them. This addresses the power imbalance between the two and greatly enhances safeguarding in an organisation.

For example, developing a knowledge of human rights in terms of protection and participation will go a long way to keeping people safe, because, as a result they are more empowered to speak up and denounce harm. In fact, there may be several outcomes, as shown in the diagram below.

(Source: Diagram adapted from information on Child Participation, Child to Child)

|

Activity 3.1 Promoting greater participation and empowerment How can organisations promote greater participation and empowerment to prevent harm? Record your response in your learning journal. |

If you would like to learn more about access to rights and empowerment, follow the links below:

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (PDF) (Child-friendly version, 1989)

- African Union Charter on the Rights and Welfare of Children (PDF) (1999)

Addressing power imbalance through participation

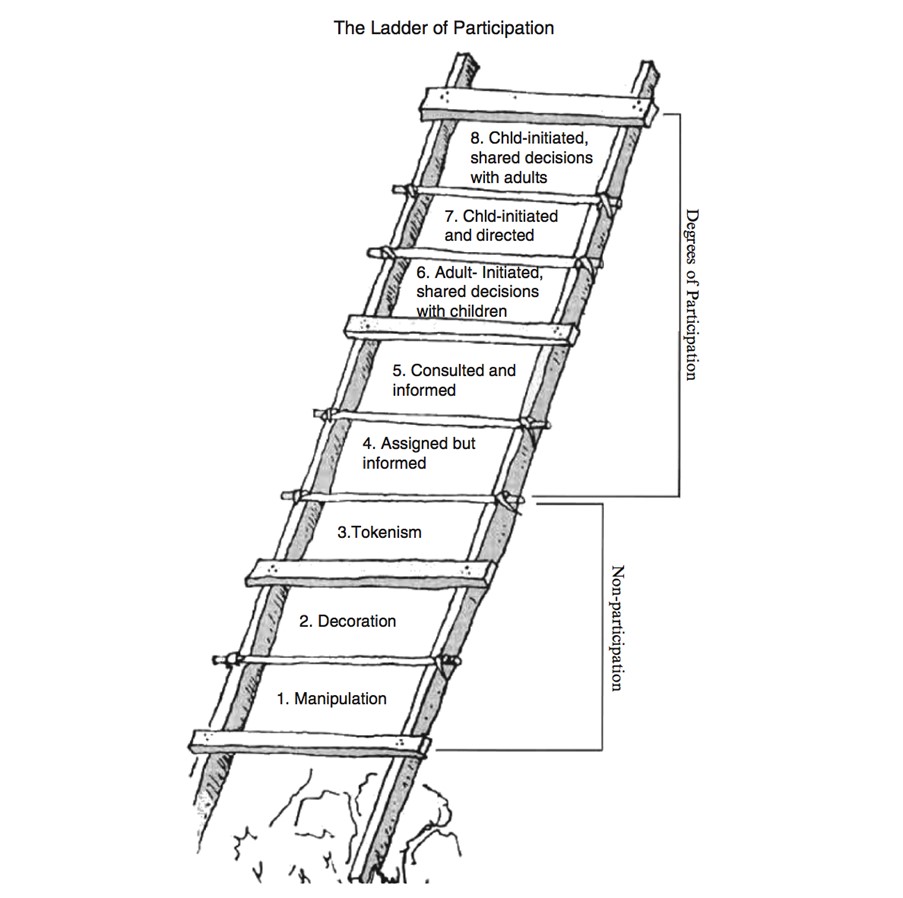

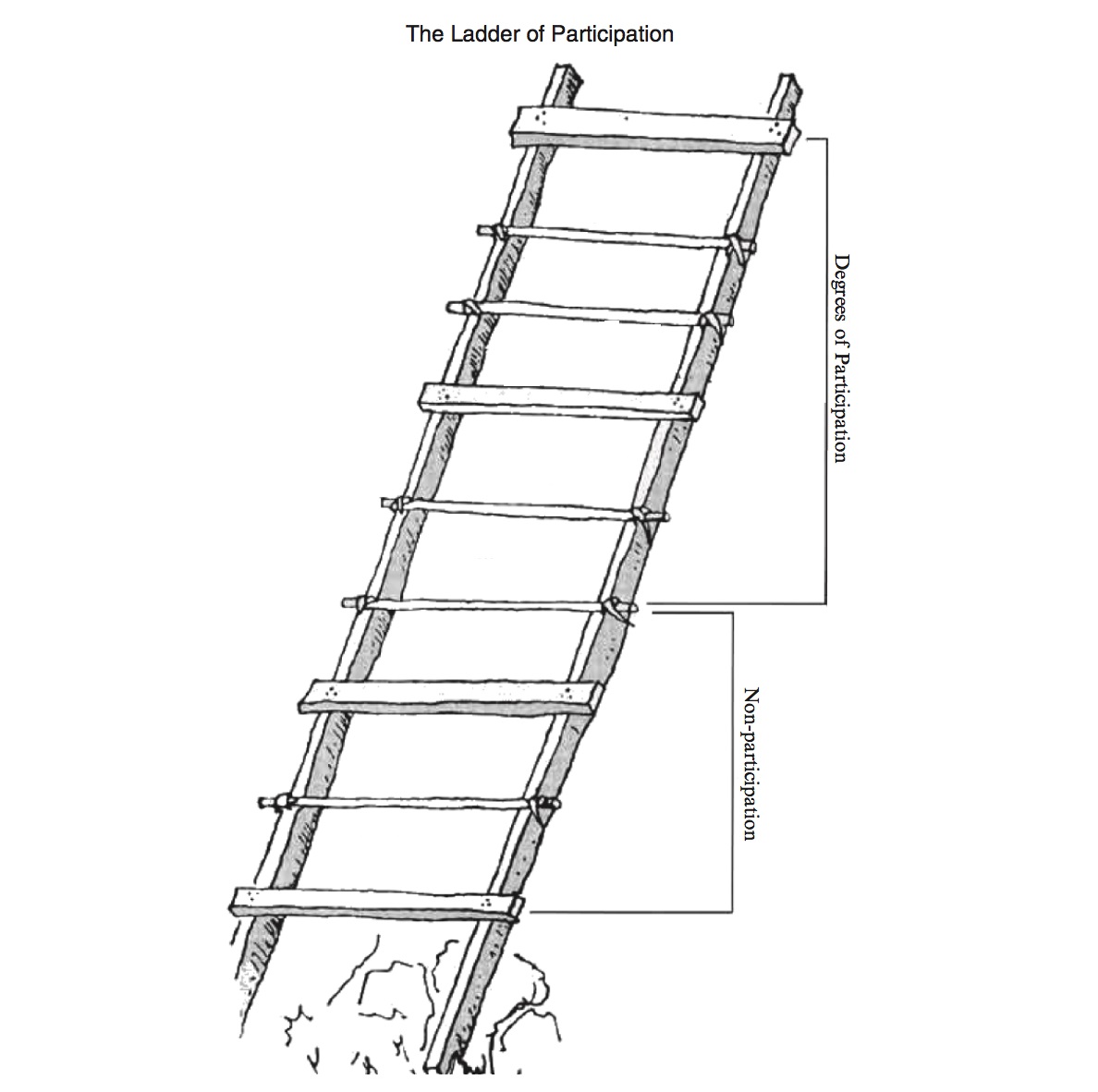

(© Roger Hart: Ladder of Participation, 2008 – amended)

In order to help us make this transition from ‘power over’ to ‘power with’, we will use an activity known as the ‘Ladder of Participation’ developed by Roger Hart.

|

Activity 3.2 The Ladder of Participation In this activity, first, look at the eight steps listed below and consider how they would fit onto the ladder in the illustration above. Rank them in ascending order, starting with where you and/or your organisation have the most power and the least participation by children or vulnerable adults. Then, second, reflect on how ‘power with’ and ‘power to’ promote a safer environment for those we work with and serve, recording your answer in your learning journal.

|

If you want to learn more about the relationship between power and safeguarding, follow the link below:

- Abusing power: Exploring issues for safeguarding RSH (1-hour webinar)

3.2 Safeguarding people with disabilities

In this section we look at the importance of safeguarding children and adults with disabilities and explore the importance of including them and their carers when developing safeguarding measures to prevent harm.

Promoting disability-inclusive safeguarding guidelines

![]()

Watch the video above by Able Child Africa on promoting disability-inclusive safeguarding guidelines. This may provide you with some ideas for the activities that follow.

How to prevent harm to people with disabilities

People with disabilities also have a right to be protected from harm as well as a right to participate, and organisations who have contact with them must ensure this.

It is widely recognised that this group is more at risk from abuse and exploitation, so we must identify this risk and prevent harm from occurring.

|

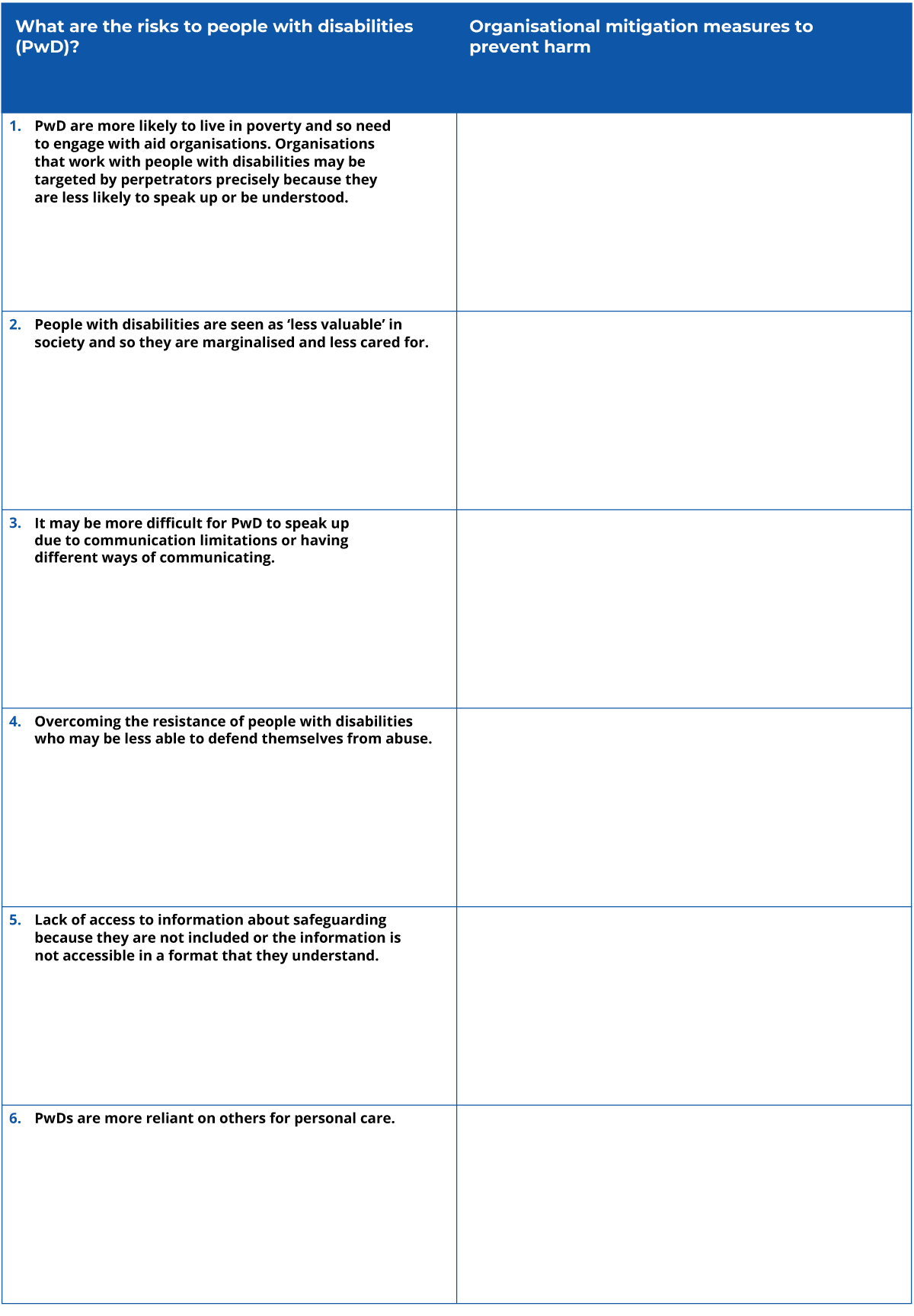

Activity 3.3 Why are people with disabilities even more at risk? (Allow 15 minutes) The table below has a list of some of the reasons why people with disabilities are even more at risk of sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment. For each reason try and think of one or more mitigating measures that would prevent harm from occurring and write your responses in the second column. If you are aware of additional reasons, you can add them below. People with disabilities – blank template Here is a writable version of the template shown below. You can type into this PDF form and then save it and/or print it.

The table below has some suggestions of mitigation actions – you may have been able to think of many other strategies for mitigation. Here is a PDF version of this table

|

If you want to learn more about safeguarding and disability, follow the links below.

- UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disability 2006

- Disability-inclusive child safeguarding guidelines Able Child Africa

- How organisations of persons with disabilities are keeping people safe | Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub (safeguardingsupporthub.org)

- Pocket Guide: Safeguarding persons with disabilities and/or mental health conditions in CSO programmes | Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub (safeguardingsupporthub.org)

- Pocket Guide: Safeguarding persons with disabilities and/or mental health conditions in the workplace | Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub (safeguardingsupporthub.org)

Case study – people with sight and hearing difficulties

Sense International is an international NGO working with people with sight and hearing difficulties.

Their work includes early identification of children who need support, helping the development of suitable school and home-based education, and offering vocational training. As well as campaigning for change, Sense International also works to strengthen local organisations and groups to support people with ‘deafblindness’ a combination of vision and hearing impairments, also described as multi-sensory impairment (MSI).

In Kenya, Sense International received a grant to implement a three-year disability inclusion project entitled Learning for all: inclusive education for learners with complex disabilities with the aim of improving developmental outcomes for children with complex disabilities in two rural counties.

The organisation has a full range of safeguarding procedures and policies in place, but because of their work with this particular group of beneficiaries they have had to consider how to promote them to make them meaningful and enhance prevention.

To do this they have used social media, local radio stations and accessible safeguarding awareness materials. They have also developed a video for parents of children with complex disabilities to help them try to create a safe environment for when their children have contact with agency workers.

|

Activity 3.4 Creating a more secure environment Watch the video above. Think about how your organisation could learn to be more inclusive in safeguarding and record your response in your learning journal. |

Promoting safeguarding with caregivers

Having watched the video in the previous section, you will have learnt that Sense International in Kenya communicated the importance of safeguarding to parents of children with sensory difficulties to help create a protective environment.

They did this by uploading a safeguarding video onto Android tablets. The parents from each county were trained on how to use the Android devices, how to access the video, the importance of the video and how to take care of the devices. They were encouraged to watch at home together with their children with complex disabilities and other family members.

The agency opted to use video technology rather than more traditional ways such as print because:

- Parents and others can watch the video at their own pace and in a more relaxed environment at home.

- They are easily accessible to all parents, most of whom have low literacy levels.

- Others in the family can also watch them, thus ensuring a child with complex disabilities receives care from all members of the family.

- It is more cost effective and environmentally friendly compared to printed materials.

In addition, telephone interviews were conducted with a sample of 12 parents to try to evaluate whether or not the information about safeguarding had been understood. It is important to try and evaluate whether our strategies are proving successful.

Safeguarding with disabled children and adults

|

Activity 3.5 The safeguarding work of Sense International Watch the video above in which Muthami Mutie, the safeguarding focal point for Sense International Kenya, talks about the safeguarding work of this agency. As you watch, note in your journal what your organisation could learn from these examples of practice. |

Prevention checklist

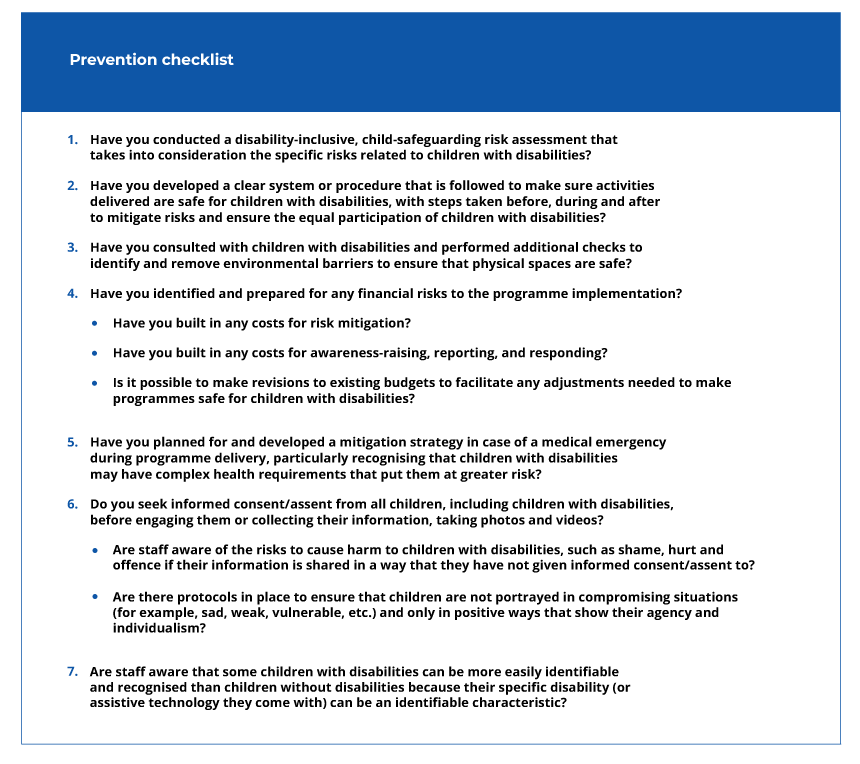

Able Child Africa has devised a tool to challenge shifting attitudes and practices when working with children with disabilities.

This ‘prevention checklist’ could be used to audit your organisational safeguarding policies and procedures in order to promote more disability-inclusive child safeguarding.

|

Activity 3.6 Prevention checklist (Allow 15 minutes) Review the checklist below and discuss with others in your organisation how you might use this tool to review policy and practice.

(© Source: Able Child Africa Toolkit) |

3.3 Safe recruitment

Safe recruitment policies and practice is a key preventative step.

Profile of sexual offenders

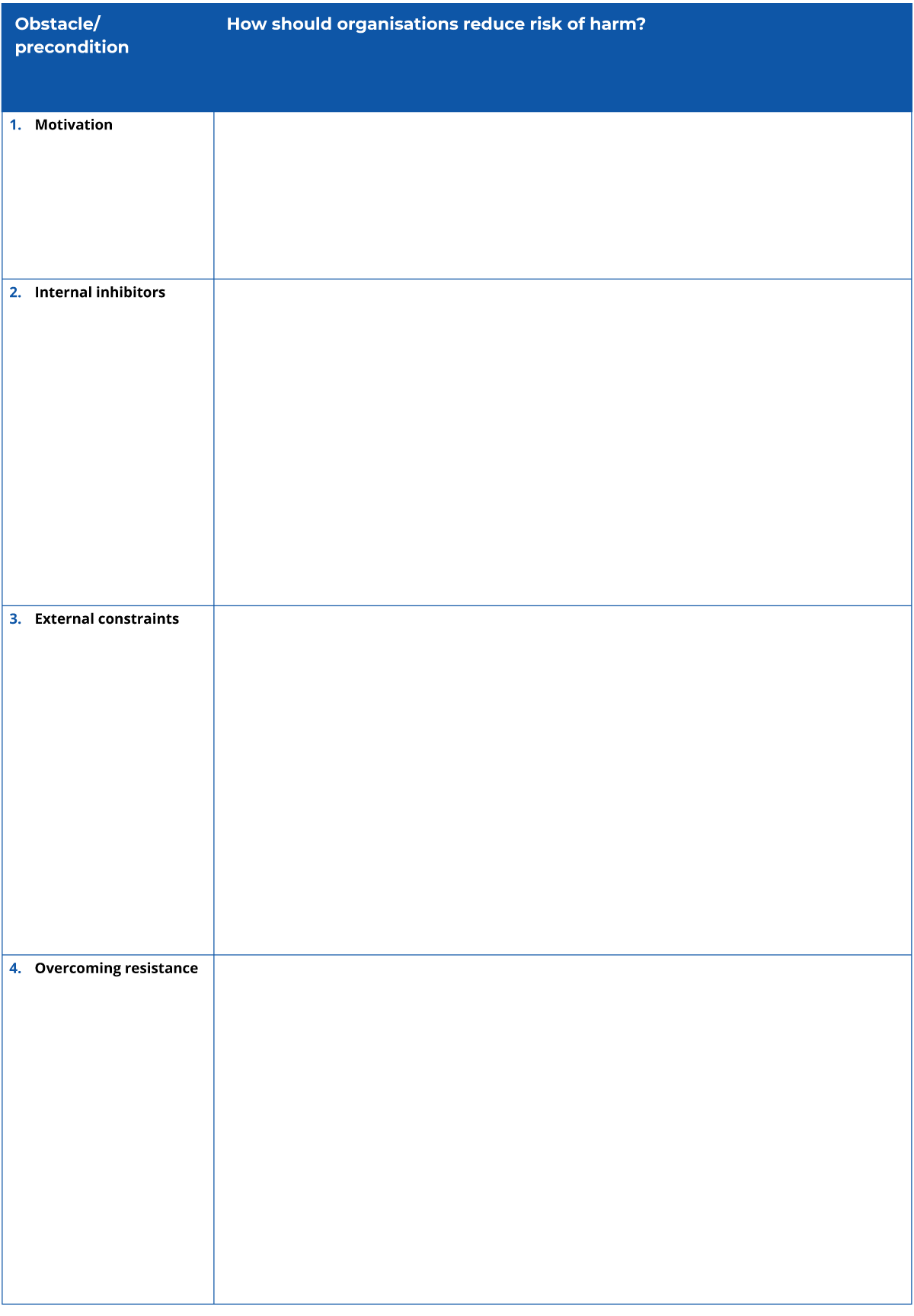

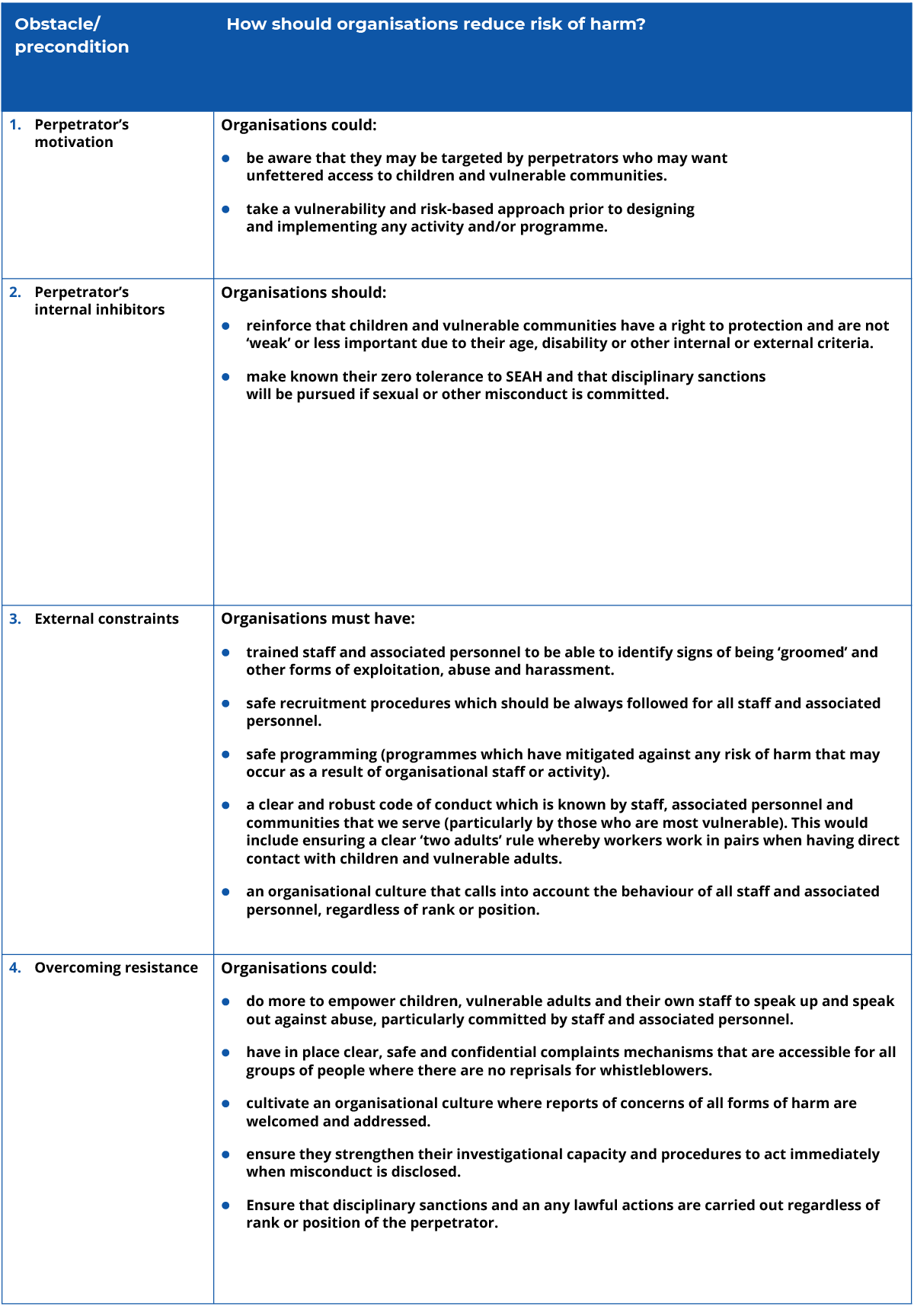

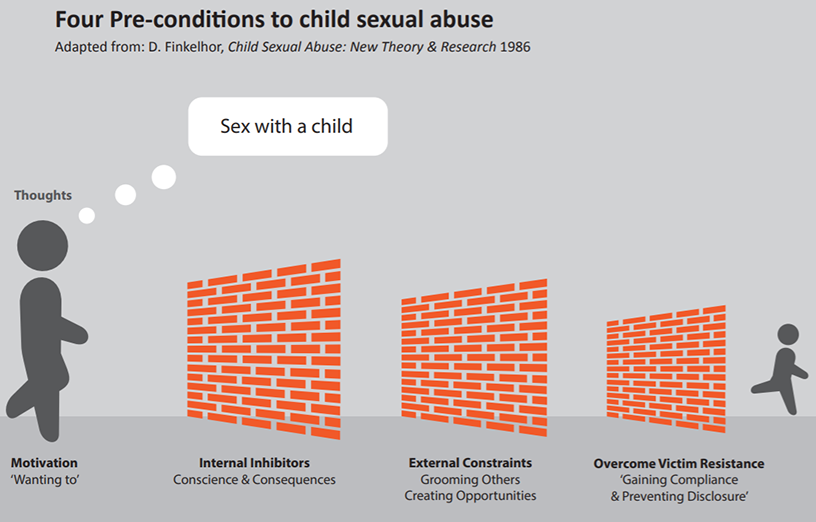

(©Source: Lucy Faithfull Foundation: Four pre-conditions to child sex abuse)

One of the biggest areas of risk for organisations who work with children and/or vulnerable adults is that posed by those who seek to sexually abuse children and vulnerable adults. Knowing more about perpetrators of sexual abuse, and their thought processes and actions, will help us strengthen our preventative measures.

One of the most significant contributions to understanding the behaviour of sexual offenders was proposed by Dr. David Finkelhor (1984) and is known as the Four Preconditions Model. This model argues that there are four preconditions, which could be seen as ‘hurdles’ or ‘obstacles’, that the sexual offender must overcome.

While the theory originally applied to those committing sexual offences against children, the same principles apply to the sexual exploitation and abuse of adults too.

Obstacle 1 (Motivation)

This is the first precondition, where sexual perpetrators already have an intention to commit sexual abuse and exploitation.

Obstacle 2 (Overcoming internal inhibitors)

Sexual abusers know that their intended actions are wrong, and so any feelings of moral conscience must somehow be overcome as well as the fear of being caught. They often find excuses to justify their actions and what motivates them to commit abuse.

Obstacle 3 (Overcoming external inhibitors)

This obstacle is when perpetrators try to access children or vulnerable adults, whether or not there are external obstacles in the way, such as robustly implemented organisational policies and procedures. Perpetrators will try and obtain jobs or volunteering opportunities that provide them access to direct or indirect contact, and they will manipulate carers/parents and staff in these organisations to obtain greater access.

Obstacle 4 (Overcoming resistance)

This is the final hurdle, where perpetrators have obtained positions of trust and gained access to their victims. At this point they would have overcome the resistance of victims as well as the adults who care for them. This is achieved through a whole range of strategies from ‘sexually grooming’ the individual, through either force, coercion, manipulation, lying or trickery, by giving gifts or making threats to prevent survivors from disclosing. If no action is taken against the perpetrator, they will re-offend and repeatedly perpetrate their abuse.

This model is useful, not only to provide an insight into the behaviour of those seeking to abuse, but also to use as a tool to enable us to identify gaps in our safeguarding measures.

|

Activity 3.7 How should organisations reduce the risk of harm? Now that you have learnt a bit more about the profile of sexual perpetrators, use the table below to identify in what you think organisations could do or should do to prevent perpetrators from overcoming the four obstacles mentioned Here is a writable version of this risk of harm template shown below. You can type into this PDF form and then save it and/or print it.

|

If you want to learn more about the Finkelhor model and how to take preventative steps, follow the links below.

- The Finkelhor model

- Steps towards prevention Lucy Faithfull Foundation

Importance of safe recruitment

In Course 1: Introduction to Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector we covered the need for organisations to ensure that they adopted safe selection and recruitment policies and practices when recruiting staff, volunteers, consultants and other associated personnel.

Part of this is to gauge candidates’ motivations for working with organisations who have access to children and vulnerable adults. Having safe and robust recruitment practices is a mitigating measure against the risk of facilitating those entering into our organisations wishing to harm children or vulnerable adults.

It is important to understand and remember that people who sexually abuse children or adults with disabilities do not usually stand out from the crowd. On the contrary, they can often be charming, friendly and helpful, and can successfully get themselves employed in education, health and care settings. They have the ability to gain the trust of children and adults with what is recognised as ‘sexual grooming’ behaviour. Before getting access to children or vulnerable adults, abusers may first have to groom the management and/or carers of an organisation.

Safe recruitment checklist

Safer recruitment practices are important, but even the best recruitment practices will not prevent those who want to abuse children and vulnerable adults being recruited by aid agencies, either in paid or unpaid capacities. That is why safe working practices and codes of conduct are also essential.

You will already be aware of the importance of safe recruitment and good practice. For example, through:

- Stating clearly in job applications that your organisation has a safeguarding policy and zero tolerance against all forms of harm, particularly sexual abuse, exploitation and sexual harassment.

- Ensuring that the interview panel (or at least one of its members) is trained in safeguarding.

- Exploring candidates’ motivations for working with children.

- Asking candidates questions specifically about safeguarding and why it is important to their roles (even when they may not have direct contact with children).

- Ensuring candidates sign a statement of commitment to your safeguarding policy and your code of conduct as a condition of employment.

- Obtaining, at a minimum, two references from previous organisations and ensuring they are verified with the previous employers by interview.

- Undertaking a check with the Misconduct Disclosure Scheme as to whether the candidate used to work with an organisation registered with the scheme.

- Undertaking a criminal record check such as the Disclosure Barring Scheme in the UK, completing a Criminal records checks for overseas applicants wanting to work for UK agencies, using the ACRO criminal records information service, obtaining a Letter or Certificate of Good Conduct (e.g. in Kenya, Uganda and many other countries) or equivalent police check.

|

Activity 3.8 Strengthening prevention for children and adults with disabilities How might you expand these preventative practices further to strengthen prevention for children and adults with disabilities? You may need to discuss this with other staff in your organisation responsible for recruiting. Record your answers in your learning journal. |

If you want to learn more about what organisations can do to improve their safeguarding guidelines, follow the link below.

The Disability-inclusive Child Safeguarding Guidelines 2021

Silent survivors – a case study

Read the following case study and then consider the questions posed at the end.

Ajij is a 25-year-old Indonesian national who volunteers in a child-friendly space (CFS) in Sulawesi, Indonesia. He lost much of his family – including a younger brother, nieces and nephews – in the 2018 tsunami. At the CFS he has become particularly close with Kadek, a deaf six-year-old, whose parents have died. With his family, Kadek had used a local sign language dialect, but nobody at the CFS knows the language. Ajij has learnt a few basic signs, but most of his communication with Kadek happens through football and art. Kadek is energetic and enthusiastic. After he scores, he waves his hands in the air and opens his mouth as if cheering. His artwork is full of playful animals, vibrant colours and bold brush strokes.

A couple of months ago, the INGO sent a new worker, Danelle, to oversee the CFS because she had a background in early childhood development and special education. Shortly after she arrived, Ajij noticed that Kadek seemed more contained than usual. He still played football with Ajij and seemed happy to see him, but his cheering was more subdued. His artwork began featuring darker colours and carefully drawn boxes. At first Ajij was concerned that Kadek was suffering from an illness. Then he began noticing a pattern. On the days when Danelle was not in the CFS, Kadek would seem more like his old self; when she was around, he was more reserved. Ajij felt confused. When he tried to get Kadek to tell him what was wrong, all the child would do is sign, “don’t like”. From his training, Ajij knew he could report a suspicion. But to whom should he report? He couldn’t go to the manager because his concerns were about her. After deliberating, he decided to raise his concerns to his organisation’s Safeguarding Focal Point (SFP).

The SFP was visibly uncomfortable about Ajij’s report, but she assured him she would inform the safeguarding committee, which then authorised an internal investigation. The SFP contacted Kadek’s aunt who was caring for him. They brought in a sign language translator to translate for Kadek. Then they interviewed other staff members and Danelle was last. The investigation determined that Danelle would shout at Kadek and pinch him in his private parts when he would not do as she was telling him to. The investigation also found out that Danelle had been warned about her behaviour towards children before. Disciplinary action was taken against Danelle according to the local Human Resources manual.

(© Adapted from Bond’s Complaint-Handling case studies)

|

Activity 3.9 Silent survivors – a case study Reflect on and respond to the following questions in your learning journal:

|

3.4 Standards of behaviour for humanitarian organisations

This section focuses on the important contribution that codes of conduct in particular can make to prevention in safeguarding.

![]()

Watch the video above which details IFRC’s code of conduct and sets out standards of behaviour for humanitarian organisations.

A Code of conduct

Having watched the IFRC video, now read Save the Children’s Code of Conduct, which provides clear guidance on what can be expected of staff, volunteers and other representatives, as well as providing examples of conduct that will always be unacceptable.

|

Activity 3.10 The importance of a code of conduct Reflect on your learning from the video and code of conduct example and respond to the following questions in your learning journal:

|

To learn more about standards of behaviour among international aid organisations, follow the links below.

3.5 Digital safeguarding

Safeguarding in the digital and online worlds has become a serious source of concern. This section considers the scale of the problem, some of the major risks, and how we might mitigate against them.

Alongside the huge advantages brought about by the internet and social media have come many challenges to safeguarding.

We connect using platforms such as Zoom, Teams, WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Slack and many others. There are high safeguarding risks associated with using these platforms if we are not clear about what is acceptable and unacceptable behaviour online.

As a result of the Covid-19 global pandemic, the use of these forms of communication has intensified, and as organisations we must ensure our staff and associated personnel understand the risks associated with using personal devices or unsupervised online contact.

One of the problems with online platforms is the amount of pornography that is available, particularly child pornography, and the ease of sharing this content.

In 2020 alone, Internet Watch Foundation identified over 150,000 web pages containing child sexual abuse imagery which represented an increase of 16% from those reported in 2019, including images of the rape of children by adults. Girls featured in over 90% of images, with the highest proportion being those between the ages of 7 and 13.

(Source: Internet Watch Foundation)

Mitigating against online abuse

The ability of perpetrators to sexually groom and exploit vulnerable children and adults online is a major safeguarding concern. For example, children and adults who are vulnerable can be tricked, persuaded, or coerced to post pictures of themselves online or post videos through the use of webcams. Once these images are created, they can be in online circulation for years, which effectively perpetuates the original abusive act.

This direct contact also facilitates the ‘grooming’ of children and enables a ‘private’ relationship to form and children to eventually be compromised via images provided or through agreeing to meet face to face.

Inappropriate relationships can easily be created by aid workers with other workers or beneficiaries using social networks, short messaging services (SMS), messaging apps, online chats, comments on live streaming sites and voice chat in games.

|

Activity 3.11 Identifying risks developing strategies Reflect on the scenarios below and note your concerns and mitigation strategies which you would put in place to reduce the risk of harm. Scenario 1 Juan is a camp manager for a children’s camp held during the school holidays. He is happy to accept Friend Requests on social media from children, their families and young volunteers. Sometimes he also initiates contact on social media. Scenario 2 Sharmila, an aid worker for a partner organisation, is in constant contact with community members through her personal mobile phone. Recently she has been receiving sexualised jokes and pictures which make her feel uncomfortable. Scenario 3 Morgan is a school counsellor and since the pandemic he carries out counselling sessions alone with a child online. Scenario 4 Peter, a Project Support Officer, likes to keep in touch with everyone and loves to link several colleagues to WhatsApp groups on his personal phone. He’ll use this to share news about beneficiaries and their families, including safeguarding concerns. Scenario 5 Leila is a researcher and provides her personal number to her research participants. These research participants now call her at all times of the day and night asking her for jobs, education opportunities, and even money. |

A question about instant messaging and social media

![]()

Sherine, a learner on this course, has a question about using instant messaging and social media platforms to keep in touch with beneficiaries and programme participants.

Watch the video above to learn more about Sherine’s question and the response she is given.

Promoting digital safety

![]()

Watch the video above on children’s data being used online and learn about UNICEF’s manifesto – a set of 10 demands to protect children in their data.

Cameras on our smart phones have been so useful in documenting real events and there is such ease in sharing this information immediately.

Often, we use personal information and data of people we serve in the same way, without written, informed consent or without any thought on how uploading that personal data leaves a ‘digital footprint’ forever – even when it’s deleted.

Children have a right to privacy under Article 16 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Promoting digital safeguarding

Technology is a wonderful innovation which can promote participation and be very inclusive to children and vulnerable adults, even when we are working remotely.

When used correctly and safely, technology can increase the participation of children and vulnerable groups and make our organisations more accountable to the communities we serve. For example, if you are a co-ordinator of a youth group, you may want to use messaging apps to stay in contact with them, creating online groups, forums and communities.

However, as explained earlier, there are risks associated with this work:

- Children and vulnerable adults may be exposed to upsetting or inappropriate content online, particularly if the platform you’re using doesn’t have robust privacy and security settings or if you’re not checking posts and comments.

- Children and vulnerable adults may be at risk of being groomed if they have an online profile that means they can be contacted privately. Note that most social media platforms have a very low age entry, which increases risk.

- Perpetrators of sexual abuse and exploitation may create fake profiles to try to contact children and vulnerable adults through the platform you’re using. For example, an adult posing as a child. They may also create anonymous accounts and engage in ‘cyberbullying’ or ‘trolling’ (online stalking). People known to a child and a vulnerable adult can also perpetrate abuse in this way.

Here’s some mitigation actions to promote digital safeguarding:

- If possible, staff and volunteers should use only work devices to contact beneficiaries, where online activity can be monitored.

- Include at least one supervisor or manager on messaging apps to ensure transparency and accountability, as well as safety for the worker concerned.

- Ensure organisations have included online and digital concerns in their safeguarding policies and that staff and associated personnel have all been trained.

- Always use appropriate language and behaviour online and do not share photos or videos that would make others feel uncomfortable or unsafe.

- Consider the right of privacy of individuals and ensure informed, written consent has been obtained.

- Ensure any online forums and communities have been set up safely.

- Ensure livestreaming webinars or online one-to-one sessions involving children and/or vulnerable adults are carried out safely and supervised closely.

- If online sessions are going to be recorded – always ask permission first. Similarly, do not take photos of online sessions without express consent.

Remember children have a right to privacy under Article 16 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

To learn more about online safeguarding policy, open this PDF file Online Safeguarding Policy (UK) NSPCC.

For guidance on digital safeguarding for children please see Digital safeguarding for migrating and displaced children | Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub (safeguardingsupporthub.org).

3.6 Unit 3 Knowledge check

The end-of-unit knowledge check is a great way to check your understanding of what you have learnt.

There are five questions, and you can have up to 3 attempts at each question depending on the question type. The quizzes at the end of each unit count towards achieving your Digital Badge for the course. You must score at least 80% in each quiz to achieve the Statement of Participation and Digital Badge.

3.7 A review of the first three units

![]()

Watch the video above, in which the Lead Academic, Jan Webb, reviews the first three units of this course Implementing Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector.

3.8 Review of Unit 3

© Feodora Chiosea / iStock / Getty Images Plus.

In this unit we looked at power and how power can be wielded in different ways, including causing harm to vulnerable communities. We also looked at the importance of how we as aid workers can share power to make our environments safer for all.

We then looked at the profile of perpetrators and the importance of ensuring there are external barriers that they are not able to overcome. We looked at this in the context of when organisations work with children and adults with disabilities when implementing programmes and how we could apply safeguarding measures.

We continued our discussions on safe recruitment, the importance of implementing a robust code of conduct and, finally, ensuring we have in place effective digital safeguarding to keep everyone safe online.

|

Learning journal

|

Now go to Unit 4: Report and respond.

References

Finkelhor. D. (1984) Child sexual abuse: New theory and research, New York, The Free Press.

Gaventa, J. (2016) ‘Finding the Spaces for Change: A Power Analysis’, IDS Bulletin: Transforming Development Knowledge, vol. 37, no. 6, Online. Available at Institute of Development Studies (Accessed 17 June 2021).

Hart, R. A. (1992) Children’s Participation: From tokenism to citizenship, Innocenti Essay Papers.

Lucy Faithfull Foundation (n.d.) ‘Steps towards prevention’, Preventing Child Sexual Abuse, Online. Available at Eradicating Child Sexual Abuse (Accessed 9 July 2021).