Innovation and accessibility

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | The online educator: People and pedagogy |

| Book: | Innovation and accessibility |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 February 2026, 10:24 AM |

Is online education inherently accessible to all?

Is online education more accessible than face-to-face education? What are the barriers to learning online? How might educators help to minimise those barriers? Share your own experiences and those of your fellow students.

Is online education more accessible than face-to-face education? What are the barriers to learning online? How might educators help to minimise those barriers? Share your own experiences and those of your fellow students.2.1 Myth: online education is more accessible than face-to-face education

There are approximately 1.3 billion disabled people in the world – that’s around a sixth of the world’s population (World Health Organization, 2023). In 2022, 27% of the EU population over the age of 16 had some form of disability. (European Council, 2023). In the European Region, the World Health Organization estimates that 36 million people may have developed Long Covid over the first three years of the pandemic (WHO, 2023). Disabled people are routinely marginalised and prevented from participating equally in many aspects of society, including education.

Meeting the needs of disabled people is a vital part of ensuring education is open to all. Most people would agree that making education open to all is ‘the right thing to do’. This idea is more formally shaped in legislation in many countries, requiring that education providers make reasonable adjustments so that learning opportunities are accessible to disabled people.

Article 24 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2008) stipulates that countries must take steps to ensure that:

Persons with disabilities can access an inclusive, quality and free primary education and secondary education on an equal basis with others in the communities in which they live;

Persons with disabilities receive the support required, within the general education system, to facilitate their effective education;

Effective individualized support measures are provided in environments that maximize academic and social development, consistent with the goal of full inclusion;

Persons with disabilities are able to access general tertiary education, vocational training, adult education and lifelong learning without discrimination and on an equal basis with others.

The UNCRPD principles apply to all forms of education, including those conducted solely online. Accordingly, claims about the many benefits of online education often include that it is:

- inherently more inclusive than face-to-face alternatives, giving educators increased opportunities to innovate and better meet the needs of diverse learners

- inherently more accessible for disabled people, removing barriers to participation that exist in face-to-face education.

At this point it’s worth noting the distinction between the terms ‘inclusion’ and ‘accessibility’. Inclusion is a broad-reaching term. When used in an educational context, inclusion refers to the removal of barriers to equal participation related to factors such as age, economic situation, disability, education level, gender, geographic location or language. However, the term accessibility specifically focuses on ensuring equal participation for disabled people.

Claims about online education being ‘inherently more inclusive’ are certainly true for some people. Online educators can innovate to make learning more engaging for diverse learners, for example through the use of interactive learning resources and videos. Geographical barriers to learning can be removed when teaching takes place solely online, opening up education to remotely located learners. Online learning also tends to offer students the opportunity to follow a fairly flexible study schedule. We should not forget, though, that in the developing world reliable access to electricity, suitable computer equipment and an internet connection – all essential for learning online – is not universal.

Claims about online education being inherently more accessible than face-to-face education are also true for some disabled learners. For example:

- Online course materials can be more accessible than printed materials for people with certain types of disability, allowing the use of screen-reading software and different display formats.

- Online tutorials can allow some disabled students to better communicate with their peers on an equal basis. For example, a deaf student or a neurodivergent student may find it difficult to interact in a face-to-face tutorial, but may have less difficulty interacting in text-based online discussions.

However, innovation in online education can sometimes come at the expense of accessibility. Cooper (2015) points out that uncaptioned videos, disorganised websites and course materials that cannot be read by screen readers or accessed without a mouse, and online educators who have little knowledge of how to ensure that their courses are accessible, compound the difficulties faced by disabled students. Sadly, more than a decade later, this is still the case (Iniesto et al, 2022).

Douce (2015) suggests that digital technologies such as virtual learning environments can help to increase levels of accessibility and inclusion. However, Pudaruth, Gunputh and Singh (2017) caution that ‘simply adopting these technologies does not ensure accessibility’. Rather, ‘educators or administrators have to make sure that these relatively new digital tools are indeed accessible to all’.

The claim that online education is inherently more accessible than face-to-face education appears, therefore, to be a myth. That said, it is within the power of online educators to make that myth a reality. Indeed, unless every online educator takes responsibility for ensuring their teaching is as accessible as possible, there’s a risk that developments in accessibility will never catch up with the fast pace of innovation in education. It needs the collective power of all educators sharing good practice and innovative ways of achieving accessibility to ensure nobody is left behind by changes in educational technology and pedagogy.

In the remainder of Week 2 you’ll look at approaches to designing inclusive and accessible online teaching and learning, how accessibility guidelines can be used to inform online learning design, and how to learn from others when designing and delivering inclusive and accessible learning experiences.

The next two steps will focus on the broader topic of inclusion before the focus of Week 2 narrows to consider accessibility in online teaching and learning.

© The Open University

2.2 Have you ever been excluded from learning online?

Exclusion from online learning can take many forms. Barriers to participation in online education include slow internet connection, computer hardware problems, a lack of skill in using online services, language barriers, the omission of text descriptions for images presented online, and the omission of transcripts for video and audio resources.

The extent of exclusion can range from entire courses being inaccessible to smaller scale difficulties in fully participating in individual learning activities.

Have you ever been excluded from learning online?

2.3 I was excluded when...

Online exclusion can take many forms and affect many different types of people, not just those with disabilities. In addition, not all potential exclusion is immediately obvious. Within the field of online education, barriers to full participation can occur for various different reasons.

Back in 2005, a survey-based study of student barriers to online learning (Muilenburg and Berge, 2005) identified eight types of barrier:

- Administrative/instructor issues

- Social interactions

- Academic skills

- Technical skills

- Learner motivation

- Time and support for studies

- Cost and access to the internet

- Technical problems

A review of barriers to learning during the first year of the Covid pandemic produced similar results (Bastos et al, 2022). It reported lack of planning, lack of resources (including limited access to devices and poor Internet connectivity), usability problems (including inadequate screen resolution and poor audio quality), and limited opportunities for interaction between learners and educators.

This discussion step prompts you to share your own experiences of being excluded from an aspect of online education. Perhaps you’ve dropped out of a course because you felt overwhelmed by the number of participants. Maybe the use of high-resolution video has been incompatible with the speed of your internet connection. Perhaps you found a requirement to regularly participate in discussions too time-consuming. Maybe you felt the imagery and examples were too far removed from your life or that the course perpetuated harmful stereotypes.

Whatever your experiences, if you are comfortable to do so, share them here with other learners. What were the consequences of your being excluded from online learning? What did you do about it? How could the situation have been improved? Has your experience as a learner affected your own teaching practice?

Discussion area

© The Open University

Are innovation and accessibility compatible?

It's a common myth that making web content accessible also makes it dull. Is this true for online learning? Can online educators be both innovative and inclusive? And what's the role of innovation in achieving accessibility?

It's a common myth that making web content accessible also makes it dull. Is this true for online learning? Can online educators be both innovative and inclusive? And what's the role of innovation in achieving accessibility?

2.4 Myth: accessibility and innovation are incompatible (Poll)

When accessibility standards for web content were first introduced, there was a commonly held fear that making online content accessible would restrict creativity, resulting in dull, boring websites. Views are changing now. However, some online educators still express concern that the constraints of making their teaching accessible will stifle the potential for innovation.

Can online learning be both accessible and innovative?

2.5 Designing accessible, innovative learning

When designing for accessible learning, the ‘universal design for learning’ (UDL) (CAST, 2018) framework is argued to promote flexibility in learning. It is grounded in the premise that accessibility should be designed into all teaching and learning, to meet the needs of all learners (not just disabled learners).

- Multiple means of representation give learners various ways of acquiring information and knowledge.

- Multiple means of expression to provide learners alternatives for demonstrating what they know.

- Multiple means of engagement to tap into learners’ interests, challenge them appropriately, and motivate them to learn.

UDL has its critics and can be a challenge to execute. For example, disability can take many forms, both seen and unseen, and the needs of one group of learners may appear in conflict with those of another group.

A counter approach is to make learning accessible by creating additional, alternative (or special) resources to meet particular needs, rather than trying to design learning that is accessible to all. Again, this position has its critics, for example, being provided with alternative resources can segregate learners or make them feel socially isolated from their peers, and can be a poor alternative to disabled students having a shared learning experience with non-disabled peers.

The two approaches are not necessarily opposites, though. Indeed, some argue that a universal design approach can include the provision of alternative or special resources.

Whichever approach is adopted when designing accessible learning experiences and resources, personas can be used either as a way of checking whether an existing learning experience is likely to meet a particular real or imagined student’s needs, or as an aid to planning a new learning experience or resource.

Next, you’ll encounter some examples of innovation that help counter the myth that accessible online learning is boring.

© The Open University

2.6 Innovations in accessibility

Innovations in online education are happening for many areas of accessibility. Some innovations will solely benefit disabled learners, while other changes have the potential to make online education more inclusive and engaging for all.

Promising areas of innovation in accessible online learning include:

- Animated avatars that are able to perform sign language

- Speech recognition and, specifically, digital personal assistants

- Artificial intelligence (AI)

- Virtual reality

- Augmented reality

- Telepresence robots

Animated signing avatars

Adding human-generated sign language videos to online resources can be costly and time-consuming. It can be difficult to find signers with expertise in signing technical language and if a resource is changed then the sign language video also needs to be edited. Animated signing avatars offer an alternative way of increasing accessibility for people who are deaf or hard of hearing.

The Virtual Humans team at the University of East Anglia have been developing animated avatars for some time. Their SignTel project applies this innovation to improving the accessibility of educational assessment. A virtual human character, or avatar signer, performs the gestures of British Sign Language signs to convey assessment questions in a manner more accessible to some deaf learners.

Related signing avatar initiatives include:

- The eSIGN project, which uses avatars for virtual signing on local government websites in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK, but also has great potential for use in online education.

- The LinguaSign project (Facebook group)which uses age-appropriate avatars performing virtual signing to teach foreign languages to deaf children.

Speech recognition and digital personal assistants

Speech recognition has been around for a long time, but has recently seen a revival of interest due to improved quality resulting from developments in artificial intelligence and in processing power, as well as the increasing popularity of personal digital assistants such as Siri and Alexa.

Voice controlled personal assistants such as Siri and Alexa are becoming more accessible, for example in recognizing computer-generated speech. Their potential for controlling aspects of the online environment is considerable. This, in turn, has implications for improving the accessibility of online learning.

While traditional methods of interacting with digital products, such as typing on a keyboard or using a touch screen, can be challenging for people with physical or cognitive disabilities, voice assistants provide a hands-free option for easier interaction with digital products. Voice assistants offer a much more natural and intuitive way of accessing information and completing tasks, which can benefit not only people with disabilities but also the general population. (Sanabria, 2023)

Artificial intelligence and machine learning

Machine learning, a component of artificial intelligence (AI), offers the ability to extract knowledge and patterns from a series of observations. Software that can understand images, sounds and language is being used to help disabled people to better interact with the world around them, including in educational contexts.

Educators have long used YouTube’s speech-to-text software to automatically caption speech in videos. Now that software can indicate applause, laughter and music in the captions. The Content Clarifier tool developed by researchers at IBM was designed to help people with cognitive or intellectual disabilities by simplifying, summarising or enhancing digital content. For example, figures of speech such as ‘raining cats and dogs’ can be replaced with plainer terms, and complex sentences can be broken down into simpler language.

Virtual reality

VR, virtual worlds and gaming feature in the initiatives described by Politis and colleagues’ 2017 paper People with Disabilities Leading the Design of Serious Games and Virtual Worlds, which details examples of the collaborative design of serious games with people who have intellectual disabilities or autistic spectrum disorder. Immersive gameplay is being used to develop employability and transferrable skills for people with autism. The paper explains that ‘autistic people have a strong preference for online interaction, which may be due to the familiar structures of online communication, the ability to choose conversation topics and/or the option of responding in one’s own time’. Virtual reality environments are also being used to teach communication skills to people with autism, again outlined in the paper.

Covering similar ground, the In Your Eyes immersive virtual reality game Freina, Bottino and Tavella (2016) was used to develop spatial perspective taking (SPT) skills in young adults with mild cognitive impairments. (The term ‘spatial perspective taking’ denotes ‘the extent to which a perceiver can access spatial information relative to a viewpoint different from the perceiver’s egocentric viewpoint (e.g. something on my right is on the left of someone facing me)’ (Clinton, Magliano and Skowronski, 2017))

In light of the revived interest in virtual worlds, research is also ongoing into ways of making them more accessible. A review of Todd, Pater and Baker’s book chapter ‘(In)Accessible Learning in Virtual Worlds’ details developments in this area, including a virtual guide dog.

Augmented reality

Augmented reality (AR) devices have been trialled in multiple learning scenarios as Blattgerste and his colleagues (2019) showed in a review of research literature in this area. Possibilities include the use of an AR platform with touch recognition to help young people with learning disabilities to understand mathematics; an AR application for handheld devices used to develop understanding of geometry; the combination of AR and emotion detection to help autistic children to learn social communication skills; and use of a handheld AR app to help young adults with cognitive disabilities to navigate a university campus.

Telepresence robots

A telepresence robot is a remote-controlled wheeled device that is connected to the Internet. The robot’s operator can see and hear what is going on around the device, and can in turn be seen and heard by people near the robot via a tablet screen. These robots enable chronically ill students to access classrooms and experience face-to-face instruction with classmates. Research has shown that these devices provide a positive experience of both educational and social development (Page et al, 2021).

© The Open University

What's the value of accessibility guidelines?

Accessibility guidelines can help online educators adapt their teaching to meet the needs of all their learners, and especially disabled learners.

Accessibility guidelines can help online educators adapt their teaching to meet the needs of all their learners, and especially disabled learners.

2.7 Myth: accessibility is difficult, expensive and time-consuming

One of the most commonly held myths associated with accessibility is that it is difficult, expensive and time-consuming. I’ll confess that when I first became an online educator I was influenced by this view, and felt overwhelmed by the prospect of embedding accessibility into my teaching.

As with the other myths I’ve addressed so far, there’s an element of truth in the claim. I’ll address cost first. Adding a human signer to hundreds of existing videos could indeed be an expensive process for an educational institution. However, adding closed captions to those videos could be achieved at little cost through a combination of automatic tools and a human checking the results.

When considering the cost of implementing accessibility, it’s also important to also consider the cost of not doing so. As already discussed, many countries have legislation requiring education providers to make reasonable adjustments so that disabled people will not experience a substantial disadvantage. Not taking such steps could result in costly compensation claims and a damaged reputation.

Moving on to the assertion that making education accessible is difficult and time-consuming, there’s an element of truth to that claim too. However, multiple resources are now available to support educators and institutions seeking to improve the accessibility of their educational provision. These resources can save you time and allow you to benefit from the expertise and experiences of others.

In this section of Week 2 you’ll look at accessibility guidelines – one example of the resources available. You’ll also draw on another resource, the shared experience of others, including your fellow students on this course.

© The Open University

2.8 Using accessibility guidelines

Designing educational resources to maximise their accessibility can be quite a challenge, especially as every learner is different. There are many different types of disability, some seen and some unseen, and people with the same disability will be affected by that disability in different ways. Accessible online learning needs to take account of this.

Accessibility guidelines can be a good place to start when planning accessible teaching strategies and learning content. As new technology emerges and people learn from the experiences of disabled people, some details in guidelines may change, some accessibility issues may disappear and other issues will take their place. Some resources describe general principles that can be applied to any new technology; others contain details that reflect current versions of particular software and will need to be kept up to date.

You may not be planning to implement accessibility guidelines yourself, perhaps because you may not be in a teaching role. However, it is still important to understand the issues the guidelines cover so that you can communicate them to anyone you commission to create resources for you, know what it is reasonable to expect to be done for the students that you support, and understand the time that might be needed to make these changes.

In the video above, filmed in Second Life, fictional art teacher Leona Simpson explains how she used accessibility guidelines to shape her teaching and better meet one learner’s needs. As you watch, consider the following questions:

- Should educators spend their precious time designing learning experiences to meet the needs of just one learner?

- Could there be any disadvantages to Leona’s approach, as described in the video?

- What might Leona have done differently?

- What might the consequences be of Leona not referring to guidelines?

- Have you had a similar experience yourself? If so, what did you do?

© The Open University

© Video: The Open University (assets PhotoDisc)

2.9 Finding relevant accessibility guidelines

Searching © Pawel Janiak on Unsplash

Searching © Pawel Janiak on Unsplash

A simple internet search for ’accessibility guidelines’ returns millions of results. So, where might you start when planning to make your teaching more accessible?

Accessibility guidelines for online education overlap considerably with more general guidelines for accessible online content. It’s therefore advised that you don’t limit your search to only education-related guidelines. If you want to cover all aspects of your teaching, the resources provided by the World Wide Web Consortium’s (W3C) Web Accessibility Initiative are particularly comprehensive. WCAG 2 at a Glance gives an overview that could be a good starting point. The page summarises the W3C overall premise that content should be perceivable, operable, understandable and robust.

Perceivable

- Provide text alternatives for non-text content.

- Provide captions and other alternatives for multimedia.

- Create content that can be presented in different ways, including by assistive technologies, without losing meaning.

- Make it easier for users to see and hear content.

Operable

- Make all functionality available from a keyboard.

- Give users enough time to read and use content.

- Do not use content that causes seizures or physical reactions.

- Help users navigate and find content.

- Make it easier to use inputs other than keyboard.

Understandable

- Make text readable and understandable.

- Make content appear and operate in predictable ways.

- Help users avoid and correct mistakes.

Robust

- Maximize compatibility with current and future user tools.

The overview page also links to more specific guidance about particular aspects of online content.

Some of the guidance from the Web Accessibility Initiative, WAI, is intended for software designers and online platform developers. However, the WAI Design and Develop Overview section is of particular relevance to online educators. Again, this section provides links to many guidelines and resources, including tips for writing, designing and developing for online accessibility.

Accessibility guidelines are often organised by resource type, rather than any other factor (such as sector or discipline). For example, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 (W3C, 2018) apply to web pages, including interactive web content. In contrast, Make your PowerPoint presentations accessible to people with disabilities (Microsoft, 2018) applies specifically to PowerPoint content. You may therefore find it useful to refine your search to focus on a specific aspect of online teaching.

© The Open University

2.10 Applying accessibility guidelines

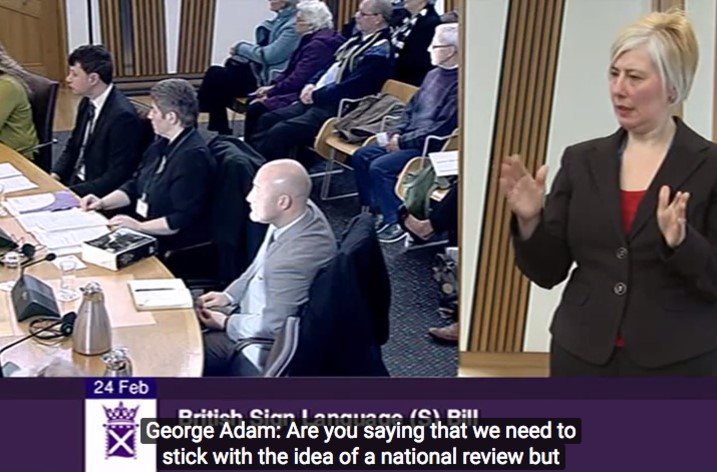

© Reproduced under the terms of the Open Scottish Parliament Licence V.2

Next, you’ll explore accessibility considerations related to just one aspect of online teaching – the use of multimedia and interactive resources. Most online educators use multimedia resources in their teaching at some point, often as part of a wider interactive learning experience. Such resources can be effective in providing engaging alternatives to text-based content, thereby helping to meet diverse learners’ needs. However, multimedia resources need careful treatment to ensure that their use does not exclude disabled learners.

The screenshot above shows a video from the Scottish Parliament featuring the use of closed captions and a signer – just two of the ways in which multimedia content can be made more accessible.

There is a wide range of online guidance available about how to make multimedia and interactive resources accessible, for example:

- The University of Washington’s Creating Video and Multimedia Products That Are Accessible to People with Sensory Impairments resource - part of their DO-IT project.

- YouTube’s Help pages on adding subtitles and closed captions to videos.

- The Multimedia section from BC Campus’ Accessibility Toolkit

Some of these guidelines may feel very technical and intended for IT developer rather than online educators. However, many educators will work in a team with IT developers and, as an educator, knowing what is technically possible can be useful when designing learning experiences.

Now, spend about 10 minutes reading one of the resources listed above and then share your response to it with your fellow learners in the discussion below. You might want to consider some of the following questions to shape your thoughts:

- To what extent do you think accessibility guidelines work?

- Who do they work best for?

- What else might you need to go with them?

- Why do you think there are so many different guidelines for the same components?

- How might you use the resources above?

- Are there other resources that you have used and can recommend?

Discussion area

© The Open University

2.11 Week 2 summary

Considering accessibility in online spaces © Alexandra_Koch on Pixabay

You’ve now come to the end of Week 2. This is a good time to reflect on what you’ve learned this week and to think about changes you might make to your own practice.

Opening up education by making learning accessible to all can have life-changing consequences on a large scale. The World Bank points out that:

Persons with disabilities are more likely to experience adverse socioeconomic outcomes such as less education, poorer health outcomes, lower levels of employment, and higher poverty rates. Poverty may increase the risk of disability through malnutrition, inadequate access to education and health care, unsafe working conditions, a polluted environment, and lack of access to safe water and sanitation. Disability may also increase the risk of poverty, through lack of employment and education opportunities, lower wages, and increased cost of living with a disability.

The European Union’s Strategy for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2021-2030 states:

There is still a considerable need for action as demonstrated by the gaps in educational outcomes between learners with and without disabilities. More young persons with disabilities leave school early and fewer learners with disabilities complete a university degree (gap of 14.4pps). […] At EU level, inclusive education has been put high on the education agenda. One of the six axes of the European Education Area is dedicated to inclusive education and lifelong learning for all.

Accessibility is therefore one aspect of being an online educator that is worth spending time on getting right, and where it’s possible to have a significant impact on people’s lives.

You’ve seen that accessibility and inclusion do not need to come at the expense of innovation. In fact, it’s arguable that inaccessible educational technology and teaching innovations are an indulgence that perpetuate the digital and educational divide.

We hope that working with your fellow students during this week has provided you with new examples of inclusive innovation and good practice. Maybe you’ll try some of them out, or you may change aspects of your practice on the basis of reading some of the accessibility guidelines you’ve encountered this week.

Developments in online education are fast-changing, and accessibility guidelines can quickly go out of date as new tools and practices are introduced. So, if you make use of social media it could be worth following accounts where the latest developments in accessible educational technology are regularly shared. To find these, search for phrases such as ‘digital accessibility’.

In the coming week you’ll look at ways of evaluating any changes you make in your teaching, and of investigating claims made by others about the impact of innovation in online education.

References

AU Press. (2016). Learning in virtual worlds: Barriers in a virtual world (A review of Todd, Pater and Baker’s book chapter ‘(In)Accessible Learning in Virtual Worlds’). Available at https://www.aupress.ca/blog/2016/04/18/barriers-in-a-virtual-world/ [blog] (Accessed:22/01/2025)

Bastos, R.A., Carvalho, D.R.D.S., Brandao, C.F.S., Bergamasco, E.C., Sandars, J. and Cecilio-Fernandes, D. (2022) ‘Solutions, enablers and barriers to online learning in clinical medical education during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review’, Medical Teacher, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 187-195.

BC Campus (2018). Accessibility toolkit, 2nd Edition: Multimedia. Available at: https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/chapter/multimedia/ (Accessed: 22/01/2025)

Blattgerste, J., Renner, P. and Pfeiffer, T. (2019) ‘Augmented reality action assistance and learning for cognitively impaired people: a systematic literature review’, in Proceedings of the 12th ACM International Conference on Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments (pp. 270-279).

Burgstahler, S. (2014). Creating Video and Multimedia Products That Are Accessible to People with Sensory Impairments. Available at: https://www.washington.edu/doit/creating-video-and-multimedia-products-are-accessible-people-sensory-impairments (Accessed: 22/01/2025)

CAST (2018) *Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2 * [online]. Available at http://udlguidelines.cast.org (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Clinton, J.A., Magliano J.P. and Skowronski, J.J. (2017) ‘Gaining perspective on spatial perspective taking’, Journal of Cognitive Psychology, vol. 30, no. 1, London, Taylor & Francis Online [online]. Available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/20445911.2017.1364254?journalCode=pecp21 (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Cooper, M. (2015) ‘Symposium report: impacts of ICT on supporting students with disabilities in higher education, Makuhari, Japan, 13 Feb 2015’, Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 93-96 [online]. Available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02680513.2015.1027885 (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Douce, C. (2015) E-learning and Disability in Higher Education [online] London, Taylor & Francis Online. Available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02680513.2015.1013529 (Accessed 13 December 2023).

European Commission (2021) Union of Equality: Strategy for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2021-2030) [online]. Available at https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2021/04/European-Strategy-2021-2030_EN.pdf (Accessed 13 December 2023)

European Council (2023) Infographic – Disability in the EU: Facts and Figures [online]. Available at https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/disability-eu-facts-figures/ (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Freina, L., Bottino, R. and Tavella, M. (2016) ‘From e-learning to VR-learning: an example of learning in an immersive virtual world’, Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, vol. 12, no. 2 [online]. Available at http://www.je-lks.org/ojs/index.php/Je-LKS_EN/article/view/1135 (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Iniesto, F., McAndrew, P., Minocha, S. and Coughlan, T. (2022) ‘Accessibility in MOOCs: the stakeholders’ perspectives’, in Rienties, B., Hampel, R., Scanlon, E. and Whitelock, D. (eds) Open World Learning: Research, Innovation and the Challenges of High-Quality Education. London: Routledge, pp. 119–130.

Judge, A. (2013) Disabilities and Virtual Worlds: An Exploration into the Experience of Learning about Self and Other, unpublished masters degree thesis, Montreal, Concordia University. Available at https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/977547/1/Judge_MA_F2013.pdf (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Krueger, A. (2013) People with Disabilities in Virtual Worlds: Who, How, Why, and What’s Next?, Denver, Virtual Ability Inc [online]. Available at https://spir.aoir.org/ojs/index.php/spir/article/view/8560/6814 (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Microsoft (2018) Making your PowerPoint presentations accessible [online]. Available at https://support.office.com/en-us/article/Make-your-PowerPoint-presentations-accessible-6f7772b2-2f33-4bd2-8ca7-dae3b2b3ef25 (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Muilenburg, L.Y. and Berge, Z.L. (2005) ‘Student barriers to online learning: a factor analytic study’, Distance Education, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 29-48 [online]. Available at https://www.cu.edu/doc/student-barriers-online-learning.pdf (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Page, A., Charteris, J. and Berman, J. (2021) ‘Telepresence robot use for children with chronic illness in Australian schools: a scoping review and thematic analysis’, International Journal of Social Robotics, vol. 13, pp. 1281-1293.

Politis, Y., Robb, N., Yakkundi, A., Dillenburger, K., Herbertson, N., Charlesworth, B. and Goodman, L. (2017) ‘People with disabilities leading the design of serious games and virtual worlds’, International Journal of Serious Games, vol. 4, no. 2. DOI: 10.17083/ijsg.v4i2.160 [online]. Available at https://pure.qub.ac.uk/portal/files/134673230/160_828_1_PB.pdf (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Pudaruth, S., Gunputh, R.P. and Singh, U.G. (2017) Forgotten, Excluded or Included? Students with Disabilities: A Case Study at the University of Mauritius [online], Bethesda, MD, National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5594265/#CIT0005 (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Sanabria, L (2023) How Voice Assistants Improve Digital Accessibility Accessibility.com. Available at https://www.accessibility.com/blog/how-voice-assistants-improve-digital-accessibility (Accessed 13 December 2023)

UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2008) Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [online]. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CRPD/Pages/ConventionRightsPersonsWithDisabilities.aspx (Accessed 13 December 2023).

W3C (2008) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 [online]. Available at http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/ (Accessed 13 December 2023).

Wikipedia (2023) Universal Design for Learning [online]. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_Design_for_Learning (accessed 13 December 2023).

Web Accessibility Initiative (2022) Design and Develop Overview [online]. Available at https://www.w3.org/WAI/design-develop/ (accessed 13 December 2023).

Web Accessibility Initiative (2023) Making the Web Accessible [online]. Available at http://www.w3.org/WAI/ (accessed 13 December 2023).

Web Accessibility Initiative (2023) WCAG 2 at a Glance [online]. Available at https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/glance/ (Accessed 13 December 2023).

World Bank (2023) Disability Inclusion [online]. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disability (Accessed 13 December 2023).

World Health Organization (2023) Disability [online]. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (Accessed 13 December 2023).

World Health Organization (2023) Statement – 36 million people across the European Region may have developed long COVID over the first 3 years of the pandemic [online]. Available at https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/27-06-2023-statement—36-million-people-across-the-european-region-may-have-developed-long-covid-over-the-first-3-years-of-the-pandemic (Accessed 13 December 2023).

YouTube Help (n.d.). Add subtitles and captions. Available at: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2734796?hl=en-GB (Accessed: 22/01/2025)

Acknowleddgements

© The Open University

2.12 Assess your understanding of Week 2

This quiz assesses your understanding of some of the issues raised in Week 2. You have unlimited attempts to complete the quiz and will be given feedback on your answers.

Quiz rules

- Quizzes do not count towards your course score, they are just to help you learn

- You may take as many attempts as you wish to answer each question

- To receive a statement of participation at the end of this course, you must achieve a minimum score of 40 on this quiz

- You can skip questions and come back to them later if you wish