Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 7 February 2026, 1:22 AM

Week 6 Collaborating across organisational boundaries

Introduction

Welcome to Week 6 of our course on collaborative leadership. This week explores collaborative leadership across organisational boundaries. You will consider whether working across organisational boundaries places particular demands on those who lead voluntary organisations, and explore the challenges and tensions of leadership in inter-organisational contexts. You will reflect on your own leadership to consider how you negotiate the challenges and tensions of working across organisational boundaries. The key practice for this week is ‘nurturing’ inter-organisational relationships.

By the end of this week, you will be able to:

- identify some of the distinctive challenges of working across organisational boundaries

- identify issues that arise for leadership in inter-organisational contexts

- offer a critical account of three ideas about leadership in inter-organisational contexts

- reflect critically on the significance of identity for inter-organisational collaboration.

- apply the idea of nurturing inter-organisational relationships, and reflect on the insight this gives to your own working practice.

1 Working across organisational boundaries

Listen to the sixth instalment of Ellen’s story.

Transcript

Like Ellen, many leaders of voluntary organisations spend large amounts of their time collaborating working with colleagues from other organisations – collaborating formally and informally to make things happen. Sometimes working with other organisations involves funding, contracts, and a clear agreement as to how organisations will work together. At other times, there is a more open agenda to explore ways of working together to make things happen in a locality, improve services for people in need, offer integrated information or make a small corner of the world a better place – whether through the arts, the environment or aid.

2 Why focus on organisational boundaries?

Working across boundaries is a common feature of voluntary sector life, often in an endeavour to address some of society’s most complex challenges – taking care of vulnerable children, providing support for older people, tackling environmental issues and promoting healthy lifestyles. These are the issues that Grint refers to as ‘wicked’ (Grint, 2005). They are also described in the academic literature as ‘relentless’ (Weber and Khademian, 2008). They are too complex for any organisation to address alone. Indeed, they are ultimately problems which persist, are unresolvable and tend to change their form over time. They therefore require the continued attention, resources, expertise and energies of multiple organisations from different sectors over an extended period of time.

Of course, inter-organisational collaboration is not confined to such serious social issues. Voluntary organisations collaborate to deliver cultural festivals and celebrations, to enhance physical space, to encourage creativity and to entertain. Even comparatively small organisations, such as self-help and residents’ groups, find themselves collaborating with other voluntary organisations and public agencies to address such aims. Community art groups collaborate with the local gallery to deliver an exhibition; residents groups collaborate with the council to manage the local community centre; and youth clubs join together to deliver a programme of holiday activities. All of these require individuals to reach across organisational boundaries to make something happen, which their organisation could not have achieved alone – we see this as a place for leadership.

2.1 An organisational perspective

A contemporary example of a wicked and relentless problem that requires the attention of many organisations is the current (2016) refugee crisis. Public agencies see their contribution to the collaborative effort to resolve the refugee crisis in terms of national concerns about immigration, welfare, school places, law and order. International aid agencies manage the delivery of aid, and continue to call for the collaborative effort to step up as the crisis worsens, and local citizen groups act to meet the immediate needs of the displaced.

Activity 1 Organisational differences

Read the article ‘The refugee crisis requires collaboration between big and small charities’, in which the author argues for the need for collaboration between informal citizen groups and large voluntary organisations in the face of the refugee crisis. As you read, consider the following questions:

- what different resources and expertise does the smaller citizen group and the large voluntary organisation each bring to addressing the refugee crisis?

- how might they work together?

- what challenges might arise?

Comment

The potential for coordinating the response of different organisations to the refugee crisis is clear. However, this example illustrates how differences in expertise, timescales, aims and motivations, together with the inclination for organisations to control and manage human actions and passions, become potential areas of challenge and conflict.

2.2 A service user perspective

In spite of such challenges, communities and individuals facing complex challenges expect organisations to provide services which are ‘joined-up’, rather than fragmented and disjointed. For example, when facing the challenges of complex healthcare situations, no one wants to spend time negotiating organisational boundaries.

Activity 2 Joined-up services

Read the article, ‘Light bulb moment: Barbara Gelb on joined up thinking’, in which a chief executive of a voluntary organisation describes how she realised the importance of joining up services across organisational boundaries when she met the parent of a dying child.

In your learning journal write about an experience you, a member of your family or someone you know has had (or draw on an example you have seen in the media), when engaging with services that don’t join up. You might want to think here about accessing a package of care for an older person or a child with a disability; or having to complete two lots of paperwork with identical information for the purposes of reporting to different parts of the state system – or any other area of life where services don’t appear to talk to each other. How did this make you feel? Make sure you title the post with the week number and the number of this activity, Week 6 Activity 2.

Comment

Most of us would agree -- service users and carers should not have to negotiate the minefield of services delivered by different organisations. Indeed, there have been many attempts to integrate services across organisational boundaries through service co-location, one-stop shops, shared referral mechanisms and other attempts to ‘hide the wiring’ behind service delivery. However, many of us know from experience that the challenges of accessing integrated services across organisational boundaries continue in spite of the endeavours of collaborating organisations and successive governments. Why is collaboration across organisational boundaries so difficult? And what kind of leadership makes things happen in these collaborative contexts?

3 Leadership

In this section, we introduce you to three ideas about leadership in collaborative contexts:

- champions from all levels maintain collaboration in spite of its challenges

- integrative leadership highlights the significance of designing structures and processes to achieve the shared purposes of collaborating organisations

- leading in inter-organisational contexts is a continual process of negotiation and trade-offs between competing tensions.

(This course can only offer a brief introduction to these ideas. You can read more in Crosby and Bryson (2005) and Huxham and Vangen (2005) – both are very readable books with a strong practice focus.)

Each of these approaches has something different to offer – each may be appropriate and useful in particular circumstances. Indeed, these approaches may overlap in practice, but they are kept separate here for the sake of offering different ideas you may find useful. A key point to note is that inter-organisational collaboration is characterised by organisational identities – differences in purpose, culture and practice – and competing as well as shared interests, which may be significant for leadership.

3.1 Challenges for champions

The academic literature recognises the importance of leadership in creating and maintaining collaboration across organisational boundaries (Crosby and Bryson, 2010; Huxham and Vangen, 2000; Vangen and Huxham, 2003). As we have suggested in previous weeks of this course, this leadership is not confined to those with management positions or titles – it is enacted by ‘champions’ at all levels who commit to the collaboration and engage others to do the same (Bryson et al., 2015).

Leading across organisational boundaries adds a layer of complexity to collaboration because each organisation has its own interests and purposes. Collaboration is possible because there is some overlap between those interests and purposes, but the distinctive identities of each organisation limit that overlap.

Activity 3 Shared purposes between champions

Watch our video discussion with Liz Gifford of Milton Keynes Council and John Cove from MK Dons Sports and Education Trust (SET).

Transcript

Now answer the following questions in your learning journal:

- what purposes do the council and MK Dons SET share?

- how might those purposes differ?

Make sure you title the post with the week number and the number of this activity, Week 6 Activity 3.

Comment

Liz and John champion the potential of collaboration because they each believe that more can be achieved for local people by working together. They recognise the importance of identifying where their organisational purposes overlap (expressed by Liz as serving the public), and the potential for bringing together their different organisational resources. However, they also recognise the different objectives and interests of their organisations and the inevitability of conflict. They each highlight the importance of building strong relationships with individuals from different organisations and sectors for the inter-organisational relationship to survive beyond such conflict.

3.2 Integrative leadership

The integrative leadership model (Bryson et al., 2015; Crosby and Bryson, 2005a; Crosby and Bryson, 2005b; Crosby and Bryson, 2010) highlights the challenges of aligning or integrating the structures and processes of collaboration. This challenge is familiar to anyone who has participated in an inter-organisational forum or project. In the early days, collaborative projects can be dominated by discussions to determine terms of reference, agree decision-making processes and accountability structures. These processes and structures then contribute to the continuing leadership of the collaboration – they make certain things possible, and others impossible. In other words, leadership of collaborations is enacted through processes and structures, as well as individuals (Huxham and Vangen, 2000).

Activity 4 Aligning processes and structures

Think back to a recent example in your own experience, and consider how much time the group spent constructing terms of reference, agreeing how to work together, determining how to make joint decisions and how each collaborating organisation is accountable to the other. (If you cannot think of an example from your experience, then think about the Local Planning Group in this week’s instalment of Ellen’s story. What processes would be it be important to agree in the first instance? How might these processes enable or limit future collaboration?)

- how did this initial work enable further collaboration?

- what processes was it important to put in place?

- what limitations did the agreed structures and processes place on the continuing collaboration?

Comment

Clearly, it makes sense to take time to determine how to collaborate, for example whether decision-making will be through consensus, majority decisions, or by authorised individuals. It is also important to reflect on how collaborative projects and forums will account to the collaborating organisations, without being dominated by organisational interests. This is a key task for leadership. However, this is not to suggest that it is possible to reach a point beyond organisational interests. Instead, the integrative leadership model suggests that collaborations should be deliberately designed to take account of different interests, strengths, and weaknesses, so that organisations complement each other in the endeavour to focus on that which is shared – achievement of a shared project, delivery of integrated services, transformation of a neighbourhood, service or community of need.

3.3 Leadership as the management of tensions

This third idea explores leadership as the management of tensions. At the heart of this idea is the concept of a tension between ‘collaborative advantage’, and ‘collaborative inertia’ (Huxham and Vangen 2005). Organisations enter collaborations to achieve collaborative advantage, something they could not achieve alone. But in practice, all too many collaborations fall into collaborative inertia – they progress slowly, achieve little, disintegrate into sectional interests and fail.

For example, the collaborative advantage of coordinating support to refugees might be that more refugees receive help, or that the needs of refugees are met more holistically than organisations could achieve if working alone. Identifying the actual or potential collaborative advantage of a collaboration is an important task for those involved in leading collaborative projects, working groups and partnerships. Indeed, if it is impossible to identify the potential collaborative advantage of a specific collaboration, then you may want to ask why it is happening at all.

However, all too often collaborative partnerships and projects become stuck in discussions about terms of reference, the processes of decision-making, and structural arrangements. Individuals find it impossible to reconcile the demands of their organisation and the need to achieve collaborative arrangements which involve compromise, and the ceding of power. Discouraged by slow progress and lack of achievement, individuals disengage from the collaboration, reinforcing the tendency to fail. The challenge for leadership is to manage the tension between the potential for collaborative advantage and the tendency towards collaborative inertia (Huxham and Vangen, 2005).

Activity 5 Advantage and inertia

Identify one example of collaboration with another organisation which features regularly in your diary (or select an example from Ellen’s story). You will work on this example through the rest of this week’s study. Try to identify an example that is part of a long-term inter-organisational collaboration. For example,

- participating in an inter-agency forum

- managing joint service delivery

- delivering an inter-agency plan for clients with complex needs

- negotiating and delivering a shared action plan with organisations working in a locality

- designing, delivering, and monitoring a joint funding bid

- developing a joint needs assessment that informs the ongoing work of collaborating organisations.

First identify the potential collaborative advantage of this collaboration. Write this down in 50 words or less.

Now identify the potential areas of collaborative inertia. Again write this down in 50 words or less.

Finally, identify any actions you might take that increase the likelihood of collaborative advantage and reduce the tendency towards collaborative inertia. Try to focus here on what you can do, rather than on the factors that constrain your actions.

Comment

Vangen and Huxham (Vangen and Huxham, 2003) write about the dilemmas which the advantage/inertia tension raises for individuals. They argue that tackling these dilemmas at times involves engaging simultaneously in activities which appear diametrically opposed to each other. On the one hand, these activities are focused on supporting the involvement and engagement of all of those collaborating, making sure everyone has a say and that all points of view are represented (an ideology of collaboration). On the other hand, they are focused on making things happen in a very pragmatic way, so that the collaboration does not become stuck – this sometimes means taking a less than inclusive approach which Vangen and Huxham (2003) describe as ‘collaborative thuggery’. Collaborative leadership therefore involves managing a tension between the ideology of collaboration and pragmatism. In other words, there is a compromise or trade-off to be made between a very inclusive participatory approach to collaboration and a pragmatic focus on getting things done in an effective way that does not consume too much time and resources.

Although Vangen and Huxham’s original research focused on the activities of partnership managers, we suggest that the approach of managing tensions is a useful one for anyone ‘leading’ in collaborative contexts, including ‘champions’ from voluntary organisations. It helps us to think about the trade-offs and compromises we are willing to make (on our own behalf and behalf of our organisation) to make things happen through inter-organisational collaboration.

For example, in a study of voluntary sector leaders collaborating with public agencies, I (Carol) found that these leaders encounter a tension between distinctiveness and incorporation (Jacklin-Jarvis, 2015). On the one hand, collaboration with the powerful public sector puts them at risk of incorporation into that sector’s agenda; on the other hand, too much emphasis on the distinctiveness of the voluntary sector risks exclusion from the resources and opportunities which the public sector brings to the collaboration table. Therefore, voluntary sector leaders can be seen negotiating a continual trade-off between assertions of voluntary sector distinctiveness and acceptance of the public sector’s agenda and priorities.

You will continue to explore this idea of managing tensions in the next activity.

Activity 6 Tensions, compromises, and trade-offs

Return to the collaboration you identified in Activity 5. Respond to the following questions in your learning journal (or if you focused on an example from Ellen’s story, then try to imagine yourself in her position in this activity):

- what kind of tensions arise in this context?

- what compromises and trade-offs do you find yourself making?

- are you comfortable with these compromises from your own perspective and from the perspective of your organisation?

Make sure you title the post with the week number and the number of this activity, Week 6 Activity 6.

Comment

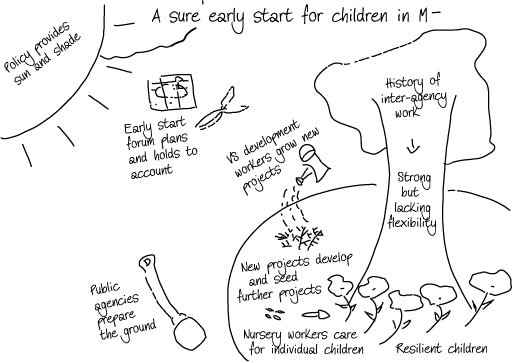

The tensions approach to leadership is a complex idea, but fortunately, Huxham and Vangen (2005) offer us an accessible way of thinking about this through the metaphor of gardening, comparing leadership in collaborative contexts to the nurturing of a garden that is lovingly tended and ruthlessly pruned.

In order to create a beautiful garden and avoid a wilderness, all gardeners know that they must pull up weeds, prune branches, and sweep away leaves, as well as feeding and protecting tender plants. In a similar way, working collaboratively across organisational boundaries requires continual attention – or nurturing – to build and sustain relationships and achieve something together that each organisation could not have achieved alone – collaborative advantage.

In the following activity, you will apply the picture of collaboration as a garden to your own context.

Activity 7 Nurturing the collaboration garden

In this activity, you will continue to think about the collaboration you identified in Activity 5, creating a picture of a garden to help you reflect on how the organisations and individuals involved in this collaboration contribute to its nurturing. We have provided you with a template to help you complete this activity.

- First, reflect on what this example of inter-organisational collaboration is trying to achieve, and give your collaboration garden a name that reflects this purpose. For example, the garden of child wellbeing in Leicester or the garden of an active older life in York.

- Next think about the kind of plants that the organisations involved in the collaboration are trying to grow together. Label these plants in the diagram. For example, a tree might represent a shared database or an agreed plan of action. Flowers might represent a healthier local population, more children engaged in sport or better access to art, heritage or the theatre. Try to be as specific as possible as you label the plants in your garden.

- Finally, think about how the organisations involved in the collaboration bring different skills, resources, and expertise to nurture the garden. This is the watering, feeding, pruning and tending of the garden. Draw in these activities, and think about the different ways in which organisations and individuals nurture the collaboration.

Try to be as creative as possible in drawing your garden, then take a photo of your picture and post it on our discussion forum. Add a comment on how drawing your garden has helped you think about the nurturing of this particular example of inter-organisational collaboration. Make sure you post your comments within the correct thread for this activity. You may also want to write about this at greater length in your learning journal.

4 Back to identity

In this discussion of inter-organisational collaboration, we have talked as if the interests and concerns of collaborating organisations are fixed. However, experience and history both tell us that this is not so – organisational identity shifts over time. Voluntary organisations which provide services for children and families provide an example of this.

Many voluntary children’s organisations began life as orphanages. As society has changed its thinking about childhood, welfare and poverty, these organisations have changed to deliver community services to families and support parents in taking care of their children. At the same time, many of these organisations separated from the faith, political and philosophical contexts in which they were established: they now reflect the more secular and multi-cultural nature of contemporary society. Some have entered into contractual relationships with public agencies, and this too impacts on their priorities and ultimately their identity.

As voluntary organisations change, they bring different values, priorities and interests into their collaborations with other organisations. So, the relationship between children’s voluntary organisations and local public agencies, for example, can be seen as a continually shifting dynamic relationship, in which the changing identities of each impact on the other. The interesting question is, then, how these changing identities impact on the endeavour to work collaboratively.

Activity 8 Changes in identity

Think about the voluntary organisation you work for (or one you know well). Can you see changes in its organisational identity in its recent past or longer history? How might those changes impact on that organisation’s collaboration with other organisations? Tell us in our discussion forum about how you see the relationship between shifting identity and inter-organisational collaboration. 'Make sure you post your comments within the correct thread for this activity.

Comment

There are numerous reasons for changes in organisational identity. As indicated above, such changes can be understood as relating to changes in wider society, but they also relate to the ways in which the individuals involved in organisations interpret and respond to societal change. In other words, organisations and collaboration between organisations are continually re-made by people and by the processes through which people engage with one another. One way of understanding this continual re-making is to see it in terms of leadership practice.

Practice of the week: nurturing

We hope you have fun designing your collaboration garden, but there is a serious point to be made (honestly!). As you continue to collaborate on behalf of your own organisation with colleagues from organisations of different sizes, with different cultures, purposes, and values, we suggest you reflect on the following questions, but also allow these questions to impact on the way you contribute to the nurturing of collaboration:

- Who is doing the nurturing? Is this a task for a specific individual (for example, a partnership manager), or are individuals from different collaborating organisations nurturing the collaboration.

- Is anyone doing the pruning and weeding? It is all too easy to avoid tackling some of the difficulties in order to avoid confrontation. Why are some organisations pulling their weight more than others? Why do some never send a representative to the meetings? Who represents which organisation anyway? And when will we stop talking and get something done? These are some of the difficult pruning questions that we often avoid when working across organisational boundaries.

- How is this nurturing impacted by the different organisations involved in the collaboration? Or is it simply a result of the energies and commitment of individuals?

- How can I contribute to the nurturing of collaboration – both by tending and by pruning and weeding?

Week 6 quiz

Check what you’ve learned this week by taking the end-of-week quiz.

To open in a new window, right click on the link above and select ‘Open in new window’.

Summary of Week 6

This week, we have begun to explore the challenges of leading across organisational boundaries. In this inter-organisational context, leaders find themselves managing tensions because the interests and purposes of collaborating organisations are not the same – even when they share an overarching purpose. This means that a certain amount of pragmatism is perhaps inevitable when leading collaboratively across organisational boundaries. For leaders of voluntary organisations, it may also mean challenging our own organisations as well as the organisations we collaborate with.

Throughout this course, we have discussed ways in which individuals lead, not because of their position, but rather through practices which probe, question and challenge, rather than accepting the status quo. We will continue to explore this questioning and challenging approach to leadership in next week’s studies.

Go now to Week 7.

Keep on learning

Study another free course

There are more than 800 courses on OpenLearn for you to choose from on a range of subjects.

Find out more about all our free courses.

Take your studies further

Find out more about studying with The Open University by visiting our online prospectus.

If you are new to university study, you may be interested in our Access Courses or Certificates.

For reference, full URLs to pages listed above:

OpenLearn – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Visiting our online prospectus – www.open.ac.uk/ courses

Access Courses – www.open.ac.uk/ courses/ do-it/ access

Certificates – www.open.ac.uk/ courses/ certificates-he

Newsletter – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ about-openlearn/ subscribe-the-openlearn-newsletter

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Owain Smolović Jones and Carol Jacklin-Jarvis.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Figure 1: © European Commission DG ECHO in Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0

Figure 2: © Chris Jones in Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

Figure 4: Jacek Dudzinski ©123RF.com

Text

Activity1: article: Stephen Morley: The refugee crisis requires collaboration between big and small charities. September 2015http://www.thirdsector.co.uk/stephen-morley-refugee-crisis-requires-collaboration-big-small-charities/article/1363673 courtesy Steve Morley steve@sangoconsulting.co.uk

Activity 2: article: Light Bulb Moment: Barbara Gelb on joined up thinking http://www.thirdsector.co.uk/light-bulb-moment-barbara-gelb-joined-thinking/management/article/1388263 courtesy http://www.thirdsector.co.uk

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.