Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 1:10 AM

Unit 10: Scots and work

Introduction

In this unit you will learn about the ways the Scots language has been used in different working environments. Language and trade obviously overlap in numerous ways, and this unit will focus on some examples from Scottish life where interesting uses of Scots have been part of working life.

There are three working environments focused on in this unit: traditional trades, specifically from Orkney and Shetland; crops and food production across Scotland; and mining, particularly in and around Ayrshire.

Important details to take notes on throughout this unit:

- Language links between Scots and the languages of Faroe, Norway and other Scandinavian countries

- Loss of vocabulary due to a loss of traditional trades and lifestyles

- Links between traditional trades and modern food production

- Scots and poverty.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the four important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these four points, as well as any assumption or question you might have. You will revisit these initial thought again when you come to the end of the unit.

10. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

- Voar

- Definition: The spring of the year.

- Example sentence: Fir da voar an hairst quarters dan schule wis oot o da question.

- English translation: For the spring and harvest quarters then school was out of the question.

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Fir da voar an hairst quarters dan schule wis oot o da question.

Model

Fir da voar an hairst quarters dan schule wis oot o da question.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word.

Related word:

- Definition: Harvest.

Example sentence: Hairst ‘ll soon be here, an aa da wark dat brings.

Example sentence: Autumn will soon be here, and all the work that brings.

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Hairst ‘ll soon be here, an aa da wark dat brings.

Model

Hairst ‘ll soon be here, an aa da wark dat brings.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word.

10.1 McColl Millar’s Modern Scots

For those learners who wish to take their study of the Scots language further, we recommend a book Modern Scots: An Analytical Survey by Robert McColl Millar. Two quotes from this essential text assist in introducing the topic of Scots and work. In Millar’s chapter “The sociolinguistics of Scots” he states:

Most Scots speakers in Scotland live in urban areas, settlements with at least 50,000 inhabitants. Yet it is rural varieties which often receive the most attention. Why is this the case?

The first explanation is inherently linguistic. Scotland is not the only industrialised country where rural dialects are more different to and discrete from the standard variety employed in that region than are their urban equivalents. In Scotland, for instance, the use of [...] words like nicht [for] ‘night’ is now confined to rural districts (and there, largely to the speech of older people); this process of retreat for this feature from urban areas is relatively recent.

Scotland’s internal divisions are many, and the sociological studies of Scotland’s urban vs rural divisions are not studies to discuss in this course in any depth. Neither are they treated in-depth in Millar’s Modern Scots: An Analytical Survey. But it is, of course, an important detail, and Millar touches on it in his text, making an important observation for this discussion:

According to the prevailing views of the nineteenth century – strangely, not that different from those held by some influential groups in the early twenty-first century – the urban poor, dependent on charity or government assistance for their daily survival, were essentially responsible for their own ill fortune.

More worryingly (for the middle classes), working people in the cities became increasingly politicised during the period, moving inexorably to the political left.

Such a movement caused a reaction among many members of the middle classes, bringing about an association between the ‘ugly’ politics of ‘King Mob’ and their ‘ugly’ speech; these associations are likely to have made many of the newly enfranchised lower middle class emphasise their difference from the working classes (from which many of them had recently risen) through embracing Scottish Standard English.

Scots in its urban form therefore became a disparaged class-associated dialect.

Keep this quote and observation from Millar in mind as you continue through the rest of this chapter. The term “rural varieties” is often used instead of “dialects” and often does assist in an understanding of the Scots language as a whole. Rural varieties implies a distance from the centre or a distinctiveness from a common dominant, and it is possibly used most by Scots language activists who wish to show respect for those outside of the centre.But to repeat a line from the Millar quote above, “Scotland is not the only industrialised country where rural dialects are more different to and discrete from the standard variety employed in that region than are their urban equivalents.” (p. 192)

As you will have learned from the previous chapters in this course, and will continue to learn about as you carry on, the Scots language has suffered from a sustained period of low status, and those wishing to promote the language have had to face innumerable struggles: two of which are dialect diversity and the imposed associations that Scots is slang or even bad English. There will be a focus in this Scots and Work chapter on the language used in areas of Scotland which, at certain points in the history of these areas, have suffered from dreadful poverty.

The people themselves, living and working in these places of poverty, were therefore not only strong Scots speakers, but also of distinct dialects of Scots.

10.2 Traditional trades in Orkney & Shetland

Like with the Scots language itself, many Scottish trades have been influenced by our Scandinavian neighbours, and we see this in the language used in the workplace – extensively so, in the Northern Isles. Both Shetland and Orkney have had, and still maintain, strong links with aquaculture and agriculture.

Farming the land and the sea have both been vital sources of income and sustenance, and the two trades often go hand-in-hand and overlap for many of the inhabitants throughout the history of the isles up to modern times.

To further set the scene I will quote once more from Robert McColl Millar:

To the north of the Scottish mainland are the Orkney and Shetland archipelagos. Although these two island chains are often lumped together, there are many ecological, cultural and historical differences between them, although similarities, such as a shared Norse heritage, need also to be borne in mind. Orkney (population in 2011: somewhat over 21,000) lies close to the Scottish mainland and is largely based on ‘soft’ sedimentary rock.

This makes most of the islands well disposed towards agriculture. In addition to the Mainland, a number of larger islands – Hoy, South Ronaldsay, Shapinsay and Westray, for instance – act as internal centres. The main population centre is Kirkwall (population in 2011: somewhat over 7,000, not including suburban development in other parishes).

Shetland (population in 2011: somewhat over 23,000) lies about 150 kilometres north of the Scottish mainland and about twice as far from both the Faroe Islands and Norway. Unlike Orkney, the geological base of Shetland is ‘hard’ igneous and metamorphic rock; soils are thin. While local level, largely subsistence, agricultural production has, at least until very recently, been an absolute necessity, fishing was for a long time the primary means both of sustenance and, where possible, profit.

Again, unlike Orkney, the Shetland Mainland is by far the largest island; even large islands like Yell and Unst are dwarfed by it. The Mainland is rarely more than five kilometres wide; often it is far narrower than this. Lerwick, with a population of around 7,000 in 2011, is essentially the only urban area.

One example from the Northern Isles which shows Scots, the language links to Scandinavia and the use of the language in a traditional trade is to look at crofting and the distribution of land. In his book, The Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland, Alexander Fenton details the history of terms for grazing areas which have been used:

In the Faroe Islands, the grazing area beyond the dyke was known as uttangards jФrð, udmark, or more often hagi. An individual’s share in the hagi was normally proportional to his holding in the indmark or township land, but whereas the indmark units were definite, demarcated and demonstrable, those in the hagi were not. The Faroese and Old Norse word hagi was used in Shetland and survives in place names and some common nouns, though it has been replaced by the word scattald, in the sense of hill-grazing.

Whilst it is now more common for stone dykes to have been replaced by fences to separate land, it is not uncommon for crofters to still share common grazing areas. These “common grazings” are where an area of land is used by a number of crofters and others who hold a right to graze stock on that land.

Today there are over 1000 common grazings covering over 500,000 ha across Scotland. A decline in the number of crofters in Scotland, and the decline of the influence of crofting, is often seen as being directly related to the decline of a wealth of Scots vocabulary due to it being specifically related to the occupation. As the trades of old become modernised, so does the language.

![]()

Can you think of other instances or contexts in which technological progress has had a huge impact on how language is used and has changed?

The lifestyle of the average Scot in previous decades and centuries has, as with so much of life across the world, changed to such an extent that people today no longer require what was once common vocabulary. We see this in the fishing industry, the crofting industry, and one where the two meet: the kelp industry.

To quote again from Alexander Fenton, we can gain an understanding of the value and uses of seaweed, which was of great importance to the Scots of the past because of its availability and its natural qualities:

The types of seaweed preferred for kelp were the wracks, Fucus and Ascophyllum, known by such names as, for example, yellow, black and prickly tang. Cutting was done by means of hooks and sickles, whose blades were toothed like harvest hooks. Collecting could start as early as mid-November, when the winter gales had torn the red-ware loose and cast it ashore.

A two-pronged fork, with prongs at right angles to the shaft, was used. This was a pick (or prick) (Orkney) or a taricrook (Shetland), the first part of the latter name coming from Norwegian tare, Laminaria. With this implement, the kelpers worked urgently in the white, rushing surf, dragging the wet, heavy ware out of the sea’s grasp, before a change of wind should wash it away again.

Summer work, cutting with the toothed sickle and gathering, was infinitely more pleasant.

As with so many necessary tasks for those living in the Northern Isles, the option to work in good weather or bad was not a choice at all. The people of Shetland and Orkney were at the mercy of the elements not only in terms of having to work in all and any conditions, but also because the threat of extremely bad weather was a real possibility and regular occurrence which could render all their hard work worthless.

So much of the work required being outside and the gathering then drying of the collected seaweed was no different. Here Fenton details the different names and techniques used across six separate Orkney locations alone:

The gathered seaweed was spread out to dry on the grass or on stone foundations or steethes (Old Scots stede, place, site 1375) at the head of the beach. The heaps, which had to be turned sometimes to prevent fermentation, had various names. A beek was, in Stronsay, a pile of tangles for kelp making, laid in tiers at right angles to each other. Other Stronsay names are build (cf. Swedish dialectal bål, heap of stuff) and kes or kace, with kyest (Norwegian dialectal kas, kos, a heap, Old Norse kasa, to heap earth on, kǫs, a heap, kǫstr, a pile) in Rousay and kokk (cock) in Birsay.

When the tangles were being heaped up to dry the broad fronds were stripped off, a process called ‘to klokk tangles’. In Walls, each man’s tangle was heaped in a kossel (from Norwegian dialectal kǫs, heap), ‘a round place above high water mark, a hollow where each man’s seaweed is collected. On the Sanday shores, a mark-stone set up between the plots of ground used by kelpers for spreading their seaweed was a dull (Old Scots dule, boundary mark, 1563), or in North Ronaldsay a met (Old Scots met, measure, 1426).

Activity 4

In this section you have come across a number of specific terms related to the kelp industry in Orkney and Shetland. In this activity you will test your memory of what these words mean. If you do not immediately remember a word, try not to look it up but work with the definitions we have provided first of all. Resort to looking it up only as a second step.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 4 items in each list.

prick, taricrook

steethe

beek, kace, kyest, kokk

dull, met

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.a mark-stone set up between the plots of ground used by kelpers for spreading their seaweed

b.a pile of tangles for kelp making

c.two-pronged fork, with prongs at right angles to the shaft

d.stone foundation at the head of the beach

- 1 = c,

- 2 = d,

- 3 = b,

- 4 = a

Whilst crofting is, in many ways, remarkably different from the flat greens of Orkney to the high, heather-clad hills of Shetland, both sets of islands share the issue of - and a passion for - getting the best out of the land with limited resources. The fact of there being a great deal more seaweed on the shores of the Orkney Isles than there is on Shetland’s is one reason why Orkney is today far greener than Shetland.

Both sets of isles used seaweed as a source of manure for the soil. The health of the land and the availability of fertilizer dictates the ability of farmers to grow crops and therefore the scale and variety of their food production.

Activity 5

As mentioned in other units, the Scots language of the Northern Isles has strong links to Old Norse. Now answer the following questions:

- What is Old Norse?

- Who spoke it and when?

- Can you find any basic Old Norse vocabulary?

- Are there any other interesting aspects of this language?

Look up the meaning and make notes – also checking what references you may have made to Old Norse when studying previous units in this course.

Answer

Old Norse was a North Germanic language that was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and Scandinavian settlements such asthe Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, as well as in parts of Russia, France, the British Isles and Ireland. It was the language of the Vikings or Norsemenand inhabitants of their overseas settlements from about the 9th to 14th centuries.

Old Norse shows close links with many of the Germanic languages today. For example, the German ja and nein, for yes and no are very similar to the Old Norse: Já and Nei. And the informal Old Norse greeting Hi is still used in English today.

Old Norse used a different alphabet from the Latin one. This Omniglot site provides useful information on the famous Runic scipt, the Old Norse alphabet.

You can find interesting Viking quotes and phrases alongside references to their origins in this article.

10.3 Crops and food production

by Annie Matheson

Redware, sloke and dulse are seaweeds which used to be eaten regularly in coastal areas, often added to soup or roasted and eaten with potatoes or a buttered bannock. In Orkney and parts of the Hebrides, children ate the raw stems of redware (also known as tangle) as a treat. “Natives of Caithness used to visit the shore at ebb tide in May to indulge in the consumption of fresh dulse and seawater. This was said to be ‘cheaper and better than Strathpeffer (spa)’ ”.

Rich in minerals, seaweed has become a fashionable food in recent years. Dulse, allegedly ‘tasting like bacon’, is hailed in some advertising as a new “superfood”.

10.4 Aittis an Bere

by Annie Matheson

For generations, oats and barley have provided the Scots with their staples in both food and drink. Most people, if asked to name the five best known traditional Scottish foods or drinks would include whisky, haggis and porridge in their choice, all of which are produced from oats or barley.

Scotland’s climate is too cool and damp to produce large quantities of wheat, but barley and oats do well, especially in the east where rainfall is lighter and there are more hours of sunshine to ripen and dry the grain. Consequently, these crops, but particularly oats, featured prominently in the past and many gastronomic variations were produced with oatmeal as the main ingredient.

It was common, particularly in the north-east, to make a week’s supply of porridge and keep it in a drawer so that slices could easily be cut off for a snack. Sowans were also a well-known peasant food, made from fermented oat husks which were boiled and drained until they formed a kind of sour gelatinous mass. Robert Burns describes ‘buttered sowans wi fragrant lunt (vapour)’ as part of the feasting at Halloween. Bannocks, although sometimes made from peasemeal or flour, were usually thick cakes of oatmeal.

Activity 6

Follow this link and look at the very large section on the combinations of food with oatmeal. Note down some of the foods that were added to oatmeal to produce another variation on the menu.

Answer

Did you find a lot of different food items that were added to oats or oatmeals to create another variation on the menu? Some of the food items that you might have found are: salt, butter, stock, milk, kail, ale.

Have you tried any of these before?

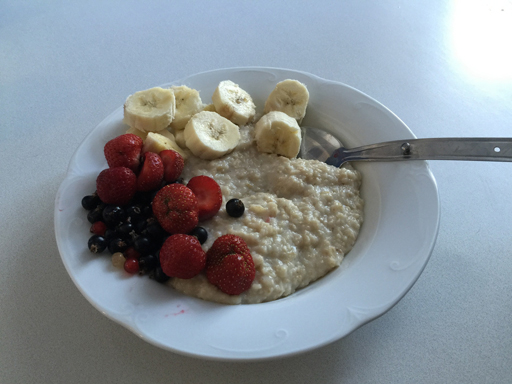

The predominance of oatmeal made the Scottish indigenous diet a very healthy one as oatmeal not only provides protein and fibre, but helps to reduce cholesterol and is said to protect against cancer. Modern chefs add all kinds of things to porridge, from bananas and blueberries to courgettes and avocados. The popular porridge-courgette mix is known in North America as zoats (z for zucchini, the American name for courgette).

This image shows a transmogrified bowl of porridge, which might be a sign of the fact that oats have become a fashionable ingredient and even contribute to an ‘oat cuisine’.

Froissier, a 14th century chronicler, describes how each soldier in Robert the Bruce’s army carried a little flat stone and some oatmeal. A paste of oatmeal and water placed on the heated stone made him a bannock when the stone was heated, like a primitive griddle, over a fire. The Scots word for such a piece of cooking equipment is different but still confusingly similar to the English term, it is girdle.

This extract from The Scots Kitchen, by F. Marian McNeill gives you an insight into a well-known oats-related tradition at Scottish universities.

Many a ‘lad o pairts’* who ultimately rose to fame studied…by guttering candlelight in a garret in which one of the most conspicuous articles of furniture was a sack of oatmeal, and regular holidays were granted by the authorities to enable the poor student to tramp back to his native glen and replenish his stock.

*a very clever lad

Activity 7

Follow this link to find out more about Mealie Monday. Take note of the key information and write a brief description of the Mealie Monday tradition.

Answer

This is a model answer, which contains key points about Mealie Monday. Your answer might be different.

Mealie Monday was a traditional Scottish University holiday to enable students to go home to replenish their oatmeal sack after the winter.As the students' country homes or farms were often some distance away from the city universities, an occasional long weekend was scheduled to permit them to replenish their supplies.

Originally, and until as recently as 1885, these Mealie Mondays would occur regularly; the University of Edinburgh, for example, had one on the first Monday of every month. However, by 1896 Edinburgh established just one official holiday, on the second Monday in February. This tradition continued and was widely observed in Scotland during the late 19th and 20th century, with Glasgow and Aberdeen Universities also having the academic holiday.

In 2006, Scottish author Alexander McCall Smith reported that "[it] was still celebrated some 30 years ago, when I was a student, although nobody used it to fetch oatmeal”

(McCall Smith, My life in a single bite, 2006)

10.5 Mining in Scotland

From the fashionable road that Scottish food has taken, and the admirable traditional trades of the Northern Isles, we now go deep into the darkness of Scotland’s mining industry where we find another once common occupation which was synonymous with the Scots language and associated vocabulary. Even the term for entering a mine, and the name given to the entrance, is a Scots one: the in-gaun een, or in-going eye.

One prolific writer on the history of the mining industry is Guthrie Hutton, who has numerous publications which shine a light into the darkness of the mining pits and the resilient lives of those plying the trade. In his book, Fife: The Mining Kingdom, Hutton (1999) acknowledges what we have discussed in terms of crofting in the Northern Isles, that many Scots words survived in common usage in the mining industry, with some regional/pit-specific variations from Fife to Ayrshire, and that more than an industry was lost when mining in Scotland ceased in the second half of the 20th century.

If the primary purpose of the mining industry was going into the land to retrieve valuable resources, it is of no surprise that the Scots word redd was in everyday use in the mines. In one context the word redd means debris, but in another, it means to clear up. Hutton explains that “[...] the act of clearing up was done in the pits by a reddsman. On the surface, the debris was tipped on the redd bing (bing means heap or pile in old Scots)” (Hutton, 1999).

Men were employed as reddsmen to clear any loose rock that had fallen on roadways, having to break up large lumps of rock before loading them into a hutch for transport to the surface where the contents would be dumped on the redd bing.

![]()

You may have taken notes when studying the Vocabulary unit, where Diane Anderson discussed the word redd and the Shetland Amenity Trust’s Da Voar Redd Up which is the UK's most successful community litter pick, with over 20% of Shetland’s population volunteering their time annually.

“This annual spring clean makes an invaluable contribution to Shetland's natural environment and wildlife, clearing Shetland's beaches, coastlines and roadsides of litter and the debris washed up by winter storms.”

Now look at the many other meanings and uses of the word redd in the Dictionary of the Scots Language.

Can you find any theme, aspect that all these uses have in common?

When reading the books of Guthrie Hutton, we are of course made aware of the hardships endured by the men, and the numerous tragedies that occurred within the industry. But, as those familiar with Scottish working class men will not be surprised to hear, there was also a great deal of humour amongst them. A joke Hutton quotes from those, who worked in the mines, was that “in the Comrie baths […] you could tell the area a man worked in because Bankhead men had webbed feet! The Bankhead area was wet whereas Langfaulds was hot and stoorie” (Hutton, Mining: Ayrshire’s Lost Industry, 1996, p. 20).

While nickie-tams is far from unique to mining, it has yet to appear elsewhere in this Scots language course, so is quoted from Guthrie Hutton here, “Conditions such as these might raise health and safety questions today, but to the indomitable people who lived here in the early 1900s the Highhouse Rows were home. This miner, sitting by the kitchen range, appears to be getting ready for work by tying his nickie-tams – pieces of string tied below the knee to hold trouser cuffs up out of the wet” (p. 71).

Nickie-tams or Nicky Tams were also worn by farmers in Scotland who had to protect their trouser legs from dragging in the dirt – as well as from any small vermin who may try and run up their trouser leg! Many songs and traditional ballads refer to nickie-tams, and there is even a traditional Scottish dance.

Activity 8

Watch this video where the Nicky Tams Sang is sung in Doric.

Then try to translate the first verse of the song into English. To access the written version of the lyrics, follow this link. You may want to use the Dictionary of the Scots Language to help you with your translation.

Answer

Your translation might be different, here is one we suggest:

When I was only ten years old I left the local school

My father apprenticed me to the farm to earn my milk and meal

Well I first put on my narrow trousers to cover my skinny legs

Then I buckled round my knocking knees a pair of nickie tams.

10.6 Sir Walter Scott’s Fair Isle visit

Situated in between Orkney and Shetland is the island of Fair Isle. Part of Shetland, residents of Fair Isle speak of “going to Shetland” the same way as residents of Shetland speak about “going to Scotland”.

The history of Fair Isle is a chronicle of a never-ending contest for survival as successive generations of Islanders battle it out against the awesome power of nature. Consider the geographical position. To the north, twenty five miles over dangerous waters to the Shetland district of Dunrossness; to the south, a similar distance to North Ronaldsay in Orkney. Straddling the east to west and north to south shipping routes, the pillared cliffs of Fair Isle are bombarded by the tides of the Atlantic and the North Sea.

This is the opening paragraph of the book Eight Acres and a Boat: Two hundred years of crofting in Fair Isle by Jerry Eunson. Chapter Two of the book, Visitors to Fair Isle (and what they thought of us), is introduced with a few comments from the author, one being “Certain visitors pulled no punches about living conditions on the Island.” (p.11) Of the twelve visitors who have their comments shared in the chapter, Sir Walter Scott has some of the most interesting opinions, which Eunson introduces as follows:

Inspection of the Scottish Signal Stations was once the province of the Sheriffs of Scotland and Sir Walter Scott participated in such a tour in 1814. This was a period when pressure was building up for lighthouses to be built around the dangerous Scottish coast. The Shetland Times gave a report of his visit to Fair Isle, which produced, in typical Scott fashion, a remarkably detailed and perceptive survey of island life and the way of life of the inhabitants.

Here are some of Scott’s observations from Fair Isle where you find references to many of the trades and details of Scottish working life which have been discussed throughout this chapter:

In front of the little harbour is the house of the tacksman, Mr. Strong, and in view are three small assemblages of miserable huts, where the inhabitants of the Isle live. There are about thirty families and 250 in habitants upon the Fair Isle. It merits its name, as the plain upon which the hamlets are situated bears excellent barley, oats and potatoes and the rest of the Isle is beautiful pasture, excepting to the eastward, where there is a moss; equally essential to the comfort of the inhabitants, since it supplies them with peats for fuel.

The inhabitants pay Mr Strong for the possessions which they occupy under him as sub-tenants and cultivate the Isle in their own way i.e. by digging instead of ploughing (though the ground is quite open and free from rocks, and they have several score of ponies), and by raising alternate crops of barley, oats and potatoes; the first and last are admirably good. They rather over-manure their crops; the possessions lie runrig; that is by alternate ridges, and the outfield or pasture ground is possessed as common to all their cows and ponies.

The manners of these islanders seem primitive and simple and they are sober, good-humoured and friendly – but ‘jimp’ honest. Their comforts are, of course, much dependent on ‘their master’s pleasure’, for so they call Mr. Strong; but they gave him the highest character for kindness and liberty and prayed to God he might long be their ruler.

Stevenson and Duff went to inspect the remains or vestiges of a Danish lighthouse upon a distant hill called, as usual, the Ward or Ward hill and returned with specimens of copper ore. Hamilton went down to catch fish for our dinner and see it properly cooked and I went to see two remarkable indentures in the coast called ‘Rivas’, perhaps from their being rifted or ‘riven’. They are exactly like the Bullar of Buchan, the sea rolling into a large open basin within the land through a natural archway.

The clergyman of Dunrossness in Zetland visits these poor people once a year, for a week or two during the summer. In winter this is impossible and even the summer visit is occasionally interrupted for two years. Marriages and baptisms are performed, as one Isles-man told me ‘by the slump’, and one of the children was old enough to tell the clergyman who sprinkled him with water: ‘The De’il be in your fingers’. Last time four couples were married and sixteen children baptised. The schoolmaster reads a portion of Scripture in the Church each Sunday when the clergyman is absent, but the present man is unfit for this part of his duty.

Fair Isle inhabitants are a good-looking race more like Zetlanders than Orkneymen. Evenson and other names of a Norwegian or Danish derivation attest their Scandanavian descent. Mr. Strong gave me a curious old chair belonging to Quendale, a former owner of Fair Isle. I will have it refitted for Abbotsford.

Activity 9

Now go back over Scott’s account of his visit to the Fair Isle and take a note of the trades and details of Scottish working life he mentions. Pay particular attention to the work that is related to producing food.

Once you have listed the items related to food and eating, test yourself and translate these words from Scott’s text into Scots language.

Answer

Here is our list of trades and working life on the Fair Isle. Your list might look different:

- Agriculture growing barley oats and potatoes

- Fishing

- Farming breeding cows for milk and meat production, and ponies as work horses

- Peat harvesting for fuel to heat houses

- Clergyman comes to visit once a year

- Teacher takes on clergyman’s duties on Sundays for the rest of the time.

And here is our suggestion for the translation of the key items in the list:

- aittis, bere, tatties

- fish

- coo and powiny, or pounnie, or poynie, or pawnie.

The final word should, in our opinion, be from Jerry Eunson, who closes Sir Walter Scott’s unit with these comments:

Scott spent but a few hours on the Island before continuing his journey south and his assessment of Fair Isle contains both a romantic gullibility of the surroundings and the intellectual arrogance and ignorance of the ‘incomer’.

In particular, the tacksman, James Strong, would have set out to impress his esteemed visitors and had succeeded. Practically everyone on the Island would agree that Strong was a tyrant. Much of the poverty was the direct result of his pitiless control of the lives of the local population.

He had it both ways, controlling both demand and supply. On the one hand, he determined how much the Islanders would receive for their fish, hosiery and other products. On the other, he set the prices for the limited but essential range of foodstuffs and materials at his shop. No competitors were permitted on the island, either as buyers or sellers. The Fair Islanders were never out of his debt.

The environment and landscapes of Shetland may contain features which make it distinct from both Orkney as well as the Scottish Borders at the furthest edge of Scotland - but the people of Shetland, together with those of Orkney, Ayrshire and the furthest south of the country all share a common history within the world of work, which, for the majority of the people, is that for generations they have had to struggle in terrible conditions against poverty.

Those in the deepest poverty were generally those who had to work in the harshest and darkest of conditions, getting little to no support, consideration or even wages from the various lairds, tacksmen and far away politicians and governments who could have their say over the future of the people - and regularly would have their say, making decisions that often put an end to both the community and a wealth of the language used there.

10.7 What I have learned

The final activity of this section is designed to help you review, consolidate and reflect on what you have learned in this unit. You will revisit the key learning points of the unit and the initial thoughts you noted down before commencing your study of it.

Activity 10

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit in the box below what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning point of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- languages links between Scots and the languages of Faroe, Norway and other Scandinavian countries

- loss of vocabulary due to loss of traditional trades and lifestyles

- links between traditional trades and modern food production

- Scots and poverty.

10.8 Where next?

You have now reached the end of part 1 of the Scots language and culture course.

Scots language and culture – part 2

Part 2 of this course gives you more in-depth insights into the role of Scots language in Scotland’s history and culture, and where you will also take a look at the future of Scots.

Part 2 contains the following units:

History and linguistic development of Scots by Simon Hall

Scots song by Steve Byrne

Storytelling, comedy and popular culture by Donald Smith

Scots and the history of Scotland by James Robertson

Scots and religion by Donald Smith

Scots abroad by Billy Kay

Grammar by Christine Robinson

Literature – poetry by Alan Riach

Literature – prose by Alan Riach

Standardisation of Scots by Michael Dempster.

Badge

Once you have completed part 2 of the course, you will have gained the knowledge that enables you to complete the course quiz. When completing the quiz successfully, you will gain a badge as proof of your successful study.

Go to Part 2 of this course.

Further research

Read Ian Tait’s Shetland Vernacular Buildings, published in 2012 by The Shetland Times Ltd. In particular the chapter “Decline of the vernacular”.

SCROLL volume 19, Scots: Studies in its Literature and Language edited by John M. Kirk and Iseabail Macleod. Published in 2013 by Rodopi. In particular the chapter “Civil Service Scots: Prose or Poetry?” by John M. Kirk.

SCROLL volume 21, Language in Scotland: Corpus-based Studies edited by Wendy Anderson. Published in 2013 by Rodopi. In particular the chapter “Civil Service Scots: Prose or Poetry?” by John M. Kirk.

Sociolinguistics in Scotland edited by Robert Lawson. Published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2014.

Go to Part 2 of this course.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Course Image: Supplied by Bruce Eunson / Education Scotland

Image in Activity 2: Ronnie Robertson. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Image in Activity 3: Ronnie Robertson. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Image in Section 10.2: Ian Balcombe. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Image in Section 10.3: Pauliene Wessel/123RF

Left image on page 15: From Pixabay. Covered under Creative Commons licence CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0)

right image on page 15 From Pixabay. Covered under Creative Commons licence CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0)

Image on page 16: From Pixabay. Covered under Creative Commons licence CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0)

Image on page 17: © balhash / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Image on page 19: Jim Barton. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Image on page 20: Map data © 2018 Google

Image on page 22: Dave Wheeler This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Go to Part 2 of this course.