Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 12:14 AM

Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Module: 10. How to Teach Health Education and Health Promotion

Study Session 10 How to Teach Health Education and Health Promotion

Introduction

This study session focuses on your work as a health educator. Health education is a very important part of your work and if you do it well it will help you improve the health of the people for whom you are responsible. In this session you will learn about teaching methods as well as some of the teaching materials you will be using in your work. Teaching methods refers to ways through which health messages are used to help solve problems related to health behaviours. Teaching materials or aids are used to help you and support the communication process in order to bring about desired health changes in the audience.

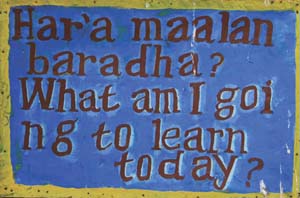

In this study session you will be able to learn about those concepts and definitions (Figure 10.1), as well as the practical application of teaching methods and health learning materials that will help you in your work.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 10

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

10.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 10.1)

10.2 Discuss some of the most important types of teaching methods. (SAQs 10.1 and 10.2)

10.3 Describe the advantages and limitations of various teaching methods. (SAQs 10.1 and 10.2)

10.3 Discuss the various types of Information Education Communication (IEC) or health learning materials. (SAQs 10.1 and 10.2)

10.4 Describe the role of IEC materials in disease prevention and health promotion. (SAQs 10.1, 10.2 and 10.3)

10.1 Teaching methods

There is a wide variety of teaching methods that you will be able to use in your health education work. You will be able to adapt these methods to your own situation, so that you can use the most effective way of communicating your health education messages.

10.1.1 Health talks

You may consider that the best way of communicating your health messages in certain situations is by using health talks. Talking is often the most natural way of communicating with people to share health knowledge and facts. In the part of your job that involves health education, there will always be many opportunities to talk with people.

Group size is also important. The number of people who you are able to engage in a health talk depends on the group size. However, you will find talks are most effective if conducted with small gatherings (5–10 people), because the larger the group the less chance that each person has to participate (Figure 10.2).

Think of some situations when you think it might be best to use health talks to get across your health education messages.

Talking is a very flexible form of communication. Talks can be conducted with one person, or with a family or a group of people, and you can adjust your message to fit the needs of that group. One example of this would be communicating a health message to a group of young mothers about their use of contraception. Even informal talks can include information about the benefits and side-effects of using contraception.

Talking to a person who has come for help is much like giving advice. But as you will see, advice is not the same as health education. To make a talk educational rather than just a chat you will find it beneficial if it is combined with other methods, especially visual aids, such as posters or audiovisual material. Also a talk can be tied into the local setting by the use of proverbs and local stories that carry a positive health message.

Preparing a talk

When you are preparing a talk there are many things to consider:

Detailed knowledge on these topics is covered in the Nutrition Module.

- Begin by getting to know the group. Find out its needs and interests and discover which groups are active in your locality.

- Then select an appropriate topic. The topic should be about a single issue or a simple topic. For example, although local people need help about nutrition, this is too big as a single topic to address in one session. So it should be broken down into simple topics such as breastfeeding, weaning foods, balanced diets, or the food needs of older people. Always ensure that you have correct and up-to-date information and look for sources of recent information. There may be leaflets available that can support your health messages.

- List the points you will talk about: Prepare only a few main points and make sure that you are clear about them.

- Next, write down what you will say: If you do not like writing, you must think carefully what to include in your talk. Think of examples, proverbs and local stories to emphasise your points and which include positive health messages

- Visual aids are a good way to capture people’s attention and make messages easer to understand. Think of what you have available to illustrate your talk. Well-chosen posters and photos that carry important health messages will help people to learn.

- Practice your talk beforehand: This should include rehearsing the telling of stories and the showing of posters and pictures.

- Determine the amount of time you need: The complete talk including showing all your visual aids should take not more than about 20 minutes. Allow another 15 minutes or more for questions and discussions. If the talk is too long people may lose interest.

Look again at the list of seven features of preparing a talk. Think about those areas in this list that you are confident about, and then those areas where you feel you will have to do some learning and practising.

The list shows the benefits of being well prepared. As you will see, only point 6 is actually about rehearsals! Most of the list is about being sure you know your audience and that you are well informed and know what you want to say and show. So, if you are nervous, then remember that you can cut down on anxiety by taking this list seriously and being very well prepared.

There are, of course other variations on talking. But all of them rely on the same key features, which are knowing your audience, being well prepared and practising.

10.1.2 Lecture

You may have the opportunity to give a lecture, perhaps in your local school or in another formal setting. A lecture is usually a spoken, simple, quick and traditional way of presenting your subject matter, but there are strengths and limitations to this approach. The strengths include the efficient introduction of factual material in a direct and logical manner. However, this method is generally ineffective where the audience is passive and learning is difficult to gauge. Experts are not always good teachers and communication in a lecture may be one-way with no feedback from the audience.

Lecture with discussion

You may have the opportunity to give a lecture and include a follow-up discussion, perhaps in a local formal setting or during a public meeting (Figure 10.3).

However there are also strengths and limitations to this approach. It is always useful to involve your audience after the lecture in asking questions, seeking clarification and challenging and reflecting on the subject matter. It’s important though to make sure discussion does happen and not just points of clarification.

10.1.3 Group discussion

Group discussion involves the free flow of communication between a facilitator and two or more participants (Figure 10.4). Often a discussion of this type is used after a slide show or following a more formal presentation. This type of teaching method is characterised by participants having an equal chance to talk freely and exchange ideas with each other. In most group discussions the subject of the discussion can be taken up and shared equally by all the members of the group. In the best group discussions, collective thinking processes can be used to solve problems. These discussions often develop a common goal and are useful in collective planning and implementation of health plans. Group discussions do not always go smoothly and sometimes a few people dominate the discussion and do not allow others to join in. Your job as the facilitator is to establish ground rules and use strategies to prevent this from happening.

Handling group members requires patience, politeness, the avoidance of arguments and an ability to deal with different people without excessive authority or belittling them publicly. Think for a moment about how you might prevent a few people from dominating a group discussion.

The key skill in group work that may prevent such domination is by encouraging full participation of everyone in the group. You may be able to ensure participation in several ways, for example by using questioning and by using other methods that facilitate active participation and interaction. Quiet or unresponsive participants need to be brought into the discussion, perhaps by asking them easy questions so that they gain in confidence. Conversely, any community member dominating the discussion excessively should be restrained, possibly by recognising his or her contribution, but requesting information from someone who has yet to be heard. Sometimes it may be necessary to be more assertive, by reminding a dominant member of the objectives of the meeting and the limited time available.

Box 10.1 gives more ideas about managing disruptive group discussions.

Box 10.1 Group disruption

Groups can be disrupted by several types of behaviour:

- People who want a fight: Do not get involved. Explore their ideas, but let the group decide their value.

- Would like to help: Encourage them frequently to give ideas, and use them to build on in the discussion.

- Focuses on small details: Acknowledge his or her point but remind them of the objective and the time limit for the discussion.

- Just keeps talking: Interrupt tactfully. Ask a question to bring him or her back to the point being discussed and thank them for their contribution.

- Seems afraid to speak: Ask easy questions. Give them credit to raise their confidence.

- Insists on their own agenda: Recognise the person’s self-interest. Ask him or her to focus on the topic agreed by the group.

- Is just not interested: Ask about their work and how the group discussion could help.

10.1.4 Buzz group

A buzz group is a way of coping if a meeting is too large for you. In this situation it is better to divide the group into several small groups, of not more than 10 or 12 people. These are called buzz groups. You can then give each small buzz group a certain amount of time to discuss the problem. Then, the whole group comes together again and the reporters from the small groups report their findings and recommendations back to the entire audience. A buzz group is also something you can do after giving a lecture to a large number of people, so you get useful feedback.

10.1.5 Demonstration

In your work as a health educator you will often find yourself giving a demonstration (Figure 10.5). This form of health education is based on learning through observation. There is a difference between knowing how to do something and actually being able to do it. The aim of a demonstration is to help learners become able to do the skills themselves, not just know how to do them.

Can you think of health related things that would be best taught through demonstration?

The whole process of measuring blood pressure, how to use a mosquito net, putting on a condom, giving a child some medicine, etc. can be best illustrated through a demonstration.

You should be able to find ways to make health related demonstrations a pleasant way of sharing skills and knowledge. Although demonstration sessions usually focus on practice — they also involve theoretical teaching as well ‘showing how is better than telling how’.

If I hear, I forget

If I see, I remember

If I do, I know.

Chinese proverb

Note that:

- You remember 20% of what you hear

- You remember 50% of what you hear and see

- You remember 90% of what you hear, see and do — with repetition, close to 100% is remembered.

Giving a demonstration

There are four steps to a demonstration:

- Explaining the ideas and skills that you will be demonstrating

- Giving the actual demonstration

- Giving an explanation as you go along, doing one step at a time

- Asking one person to repeat the demonstration and giving everyone a chance to repeat the process (Figure 10.6).

Qualities of a good demonstration

For an effective demonstration you should consider the following features: the demonstration must be realistic, it should fit with the local culture and it should use familiar materials. You will need to arrange to have enough materials for everyone to practice and have adequate space for everyone to see or practice. People need to take enough time for practice and for you to check that everyone has acquired the appropriate skill.

Zahara is a Health Extension Practitioner. She is working in Asendabo kebele. During home visits she educates the families by showing them demonstrations on how to prevent malaria. List at least three features of an effective demonstration that Zahara should follow during her health education activities.

For the demonstration to be effective Zahara should consider the following important points: the materials that she might use and the demonstration process should be real. So, for example, she should have real bed netting with her and at least something she can use that is like a bed. The demonstration should fit with the local culture and she should explain what she is doing as she goes along. She should make sure that there is enough time for at least one person to repeat the demonstration of fitting the bed netting and, if at all possible, for everyone to practice doing it.

10.1.6 Role play

In role play, some of the participants take the roles of other people and act accordingly. Role play is usually a spontaneous or unrehearsed acting out of real-life situations where others watch and learn by seeing and discussing how people might behave in certain situations. Learning takes place through active experience; it is not passive. It uses situations that the members of the group are likely to find themselves in during their lives. You use role playing because it shows real situations. It is a very direct way of learning; participants are given a role or character and have to think and speak immediately without detailed planning, because there is usually no script. In a role playing situation people volunteer to play the parts in a natural way, while other people watch carefully and may offer suggestions to the players. Some of the people watching may decide to join in with the play.

The purpose of role play is that it is acting out real-life situations in order that people can better understand their problems and the behaviour associated with the problem. For example, they can explore ways of improving relationships with other people and gain the support of others as well. They can develop empathy, or sympathy, with the points of view of other people. Role play can give people experiences in communication, planning and decision making. For example it could provide the opportunity to practice a particular activity such as coping with a difficult home situation. Using this method may help people to re-evaluate their values and attitudes, as the examples in Box 10.2 illustrate.

Box 10.2 Examples of role play

- Ask a person to get into a wheelchair and move around a building to develop an understanding of what it feels like to have limited mobility.

- Ask the group to take up the roles of different members of a district health committee. One person acts as the health educator and tries to convince the people to work together and support health education programmes in the community. Problems of implementing health education programmes and overcoming resistance can be explored in the discussion afterwards.

- Ask a man to act out the role of woman, perhaps during pregnancy, to develop an understanding of the difficulties that women face.

Role play is usually undertaken in small groups of 4 to 6 people. Remember role play is a very powerful thing.

- Role play works best when people know each other.

- Don’t ask people to take a role that might embarrass them.

- Role play involves some risk of misunderstanding, because people may interpret things differently.

Look at the three examples of role play in Box 10.2. What dilemmas might arise in each situation?

Here are some possible dilemmas. If a person in your group is already in a wheelchair you would need to handle the role play very carefully. If anyone in your group is in a dispute with someone on the health education committee they might take the opportunity to be spiteful. If a man is acting the role of a woman he would need to feel comfortable doing this. If it looks as though he is very embarrassed you would need to ask for another volunteer or change what you are doing.

10.1.7 Drama

Drama is a very valuable method that you can use to discuss subjects where personal and social relationships are involved. Basic ideas, feelings, beliefs and values about health can be communicated to people of different ages, education and experience. It is a suitable teaching method for people who cannot read, because they often experience things visually. However the preparation and practice for a drama may cost time and money.

The general principles in drama are:

- Keep the script simple and clear

- Identify an appropriate site

- Say a few words at the beginning of the play to introduce the subject and give the reasons for the drama

- Encourage questions and discussions at the end.

10.1.8 Traditional means of communication

Traditional means of communication exploit and develop the local means, materials and methods of communication, such as poems, stories, songs and dances, games, fables and puppet shows.

Some of the benefits of traditional means of communication are that they are realistic and based on the daily lives of ordinary people; they can communicate attitudes, beliefs, values and feelings in powerful ways; they do not require understanding that comes with modern education in the majority of instances; they can communicate problems of community life; they can motivate people to change their behaviour and they can show ways to solve problems. Local traditional events are usually very popular and they can be funny, sad, serious or happy. Also, they are easily understood and they usually cost little or no money. All they require is imagination and practice.

Remember that effective health education is seldom achieved through the use of one method alone. Therefore, a combination or variety of methods should be used to make sure that people really understand your health education messages.

Think of an important health issue in your own community. What methods do you think might be best to deliver health messages about this subject to members of your own community? Read Section 10.1 again and see which methods seem to fit in with your community.

Your answer will be different depending on factors that affect the message you want to deliver. For example, if skills need to be taught then a demonstration is a good method. If your objective is to improve awareness, lecturing may be a good method. Your methods may also vary depending on your own knowledge of your community. For example, you may know several people who enjoy ‘play acting’ and this would make drama and role play quite attractive methods. Also if you have someone in your community who is very good at telling stories or fables, or singing, then you may be able to work with them to help you deliver your messages.

10.2 Health learning materials

Health learning materials are those teaching aids that give information and instruction about health specifically directed to a clearly defined group or audience. The health learning materials that can be used in health education and promotion are usually broadly classified into four categories: printed materials, visual materials, audio and audio-visual materials.

10.2.1 Printed materials

Printed health learning materials can be used as a medium in their own right or as support for other kinds of media. Some printed health learning materials that you will already be familiar with include posters, leaflets and flip charts.

Posters

In recent years, the use of posters in communicating health messages has increased dramatically (Figure 10.7). Since a poster consists of pictures or symbols and words, it communicates health messages both to literate and illiterate people. It has high value to communicate messages to illiterate people because it can serve as a visual aid.

The main purposes of posters are to reinforce or remind people of a message received through other channels, and to give information and advice — for example to advise people to learn more about malaria. They also function to give directions and instructions for actions, such as a poster about practical malaria prevention methods. Posters can also serve to announce important events and programmes such as World Malaria Day.

Visual aids like posters explain, enhance, and emphasise key points of your health messages. They allow the audience to see your ideas in pictures and words. Box 10.3 gives some tips on preparing posters.

Box 10.3 Preparing a poster

- Written messages should be synchronised with pictures or symbols.

- All words in a poster should be in the local language or two languages.

- The words should be few and simple to understand. A slogan might contain a maximum of seven words.

- The symbols used should be understood by everyone, whatever their educational status.

- The colours and pictures should be ‘eye-catching’ and meaningful to local people.

- Put only one idea on a poster. If you have several ideas, use a flip chart (see below).

- The poster should encourage practice-action oriented messages.

- It is better to use real-life pictures if possible.

- It should attract attention from at least 10 metres away.

Flip chart

Flip charts are useful to present several steps or aspects that are relevant to a central topic, such as, demonstration of the proper use of mosquito nets or how HIV is transmitted. When you use the flip chart in health education you must discuss each page completely before you turn to the next and then make sure that everyone understands each message. At the end you can go back to the first charts to review the subject and help people remember the ideas.

Leaflets

Leaflets are the most common way of using print media in health education. They can be a useful reinforcement for individual and group sessions and serve as a reminder of the main points that you have made. They are also helpful for sensitive subjects such as sexual health education. When people are too shy to ask for advice they can pick up a leaflet and read it privately.

In terms of content, leaflets, booklets or pamphlets are best when they are brief, written in simple words and understandable language. A relevant address should be included at the back to indicate where people can get further information.

Think for a moment about how you have seen printed materials used for health education messages. Think about posters which have been successful and made an impact, about how other health educators have used flip charts. So you can always ‘copy’ the way that other people do things. If you have a talent yourself or know someone else who does, you can experiment with posters and flip charts (Figure 10.8).

10.2.2 Visual materials

Visuals materials are one of the strongest methods of communicating messages, especially where literacy is low amongst the population. They are good when they are accompanied with interactive methods. It is said that a picture tells a thousand words. Real objects, audio and video do the same. They are immediate and powerful and people can play with them!

Think about what real visual materials you might take with you to a health education meeting. We’ve already mentioned bed netting for demonstrating prevention of malaria, but there are other real objects too. Think about family planning, nutrition, hygiene and so on.

If your display is on ‘family planning methods’, display real contraceptives, such as pills (Figure 10.9), condoms, diaphragms, and foams. If your display is on weaning foods, display the real foods and the equipment used to prepare them.

10.2.3 Audio and audio-visual materials

Audio material includes anything heard such as the spoken word, a health talk or music. Radio and audio cassettes are good examples of audio aids. As the name implies, audio-visual materials combine both seeing and listening. These materials include TV, films or videos which provide a wide range of interest and can convey messages with high motivational appeal. They are good when they are accompanied with interactive methods. Audio-visual health learning materials can arouse interest if they are of high quality and provide a clear mental picture of the message. They may also speed up and enhance understanding or stimulate active thinking and learning and help develop memory.

Summary of Study Session 10

In Study Session 10, you have learned that:

- To be most effective you will have to decide which type of teaching methods and materials will suit the specific messages that you want to convey. It is also important to understand who your target groups are and what resources you have at hand to meet your communication objectives.

- The most important teaching methods are talks, lectures, group discussions, buzz groups, demonstrations, role-plays, dramas and traditional means of communication such as poems, stories, songs, dances and puppet shows.

- Health learning materials include posters, flip charts and leaflets, visual materials such as real objects, and audio-visual material such as TV, films and videos.

- Often more than one approach is more effective than a single type of activity. Using the right teaching methods and learning materials for the right target group in your health education programme helps you to convey effective messages to individuals and communities. This stands the best chance of bringing about health-related behavioural change.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 10

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 10.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1, 10.2, 10.3 and 10.4)

Explain the difference between teaching methods and health learning materials and give examples of each of them.

Answer

Teaching methods are ways through which health messages are conveyed. Learning materials are printed, visual or audio-visual aids that are used to help you and support the communication process, in order to bring about desired health changes in the audience. Examples of learning methods are: lecture, lecture with discussion, role play and drama. Examples of teaching materials are: posters, leaflets and flipcharts.

SAQ 10.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.2, 10.3 and 10.4)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case explain why it is incorrect.

A The health education method which is superior to any other method is drama.

B The lecture method is good for helping an individual with their health problems.

C Role play is a method which is spontaneous and often unscripted.

D The teaching method that has the saying ‘Telling how is better than showing how?’ is the demonstration method.

E A poster should contain more than one idea and its importance is to give information only.

Answer

A is false. In health education there is no method which is superior to any other method. Choice of methods depends on some important points that need to be taken into consideration. The method must suit the situation and the problem, so before choosing a method the person delivering health education must understand the problem at hand and the background of the audience.

B is false. A lecture is usually a spoken, factual way of presentation of the subject matter to many people. It is passive teaching because there is no opportunity for individual health problems to be discussed in lecture methods.

C is true. Role play is a spontaneous or unrehearsed acting out of real-life situations where others watch and learn by seeing and discussing how people behave in a certain situations. There is usually no script.

D is false. In a demonstration ‘showing how’, is better than ‘telling how’.

E is false. Each poster should contain one idea. Its importance is more than just giving information. A poster can reinforce or remind people about a message that has been received through other channels; give information and advice; or give directions and instructions for actions. It may also announce important events and programmes.

SAQ 10.3 (tests Learning Outcome 10.4)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case explain why it is incorrect.

A Audio-visual materials and real objects are particularly useful in situations where the literacy rate of a group is very high.

B Real objects are useful learning aids because people can actually see and touch them — and they are immediate.

C Audio-visual materials and real objects are used only as a last resort when there are not enough posters to show.

D Demonstrations are activities where the use of real objects enhances the learning that people achieve.

Answer

A is false. In fact just the opposite is true. It is generally thought that audio-visual materials and real objects work well with audiences where the level of literacy is low.

B is true. Real objects can help people literally have a ‘hands on’ learning experience which can be very powerful.

C is false. Real objects and audio-visual materials are suitable for some circumstances and posters for others. Sometimes you will want to use all of them. It is a matter of knowing what will be effective for your audience.

D is true. Demonstrations are the ideal place to use real objects. In fact if you do not use real objects (or models) in demonstrations then you will not be able to show how to do something in a convincing way.