Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 8:53 PM

Session 5 The facilitation of Living Labs

Session 5 The facilitation of Living Labs

Facilitation was a critical feature of the AgriLink Living Labs. First, watch the following video which introduces facilitation and then move on to the next section to do the reflective activity.

Transcript

NOELIA TELLETXEA SENOSIAIN:

A Living Lab does not run itself. While it's a participatory process, someone needs to take responsibility for ensuring that activities are planned and run effectively. For the process to be creative, someone also needs to help people to engage with the complexity of the situation and draw out insights from the different perspectives of those involved.

This is not about dictating to others what should happen, but in consulting with them as to what needs to be done, how, when, and by whom. This is where facilitation becomes important to ensure active user involvement and stakeholder engagement.

So in this session we look at what facilitation is in principle and look at some examples of facilitation within AgriLink's Living Labs.

Now go to the next section.

What is facilitation?

Reflective Activity 10

Reflective Activity 10

What experiences do you have of being facilitated or being a facilitator in your work? How do you think facilitation could be used in a Living Lab?

Answer

There are many similar definitions of facilitation, such as this one from the Cambridge English Dictionary: ‘the act of helping other people to deal with a process or reach an agreement or solution without getting directly involved in the process, discussion, etc. yourself’. In other words, you do not lead or impose what happens, you support the process and should not have a personal stake in the outcome. This may be what you are familiar with, but it is not quite how we used facilitation in AgriLink, which is set out by Kevin Collins of The Open University in his AgriLink Practice Abstract on Facilitation in Living Labs:

Facilitation is the process of making something easy or easier in order to achieve an aim. It is usually done by an independent person, or facilitator, designing and running a meeting or events for participants to understand their situation and develop new ideas and practices. In environmental contexts, facilitation is often associated with helping to resolve conflicts or disagreements, such as how land should be managed or how water resources should be allocated. In AgriLink, facilitation is understood more broadly as a process of inquiry or learning about complex situations. This framing enables new ways of thinking about and ‘doing’ facilitation.

In particular, the Living Labs themselves are seen as a form of facilitation that brings together diverse stakeholders (including researchers) in more open and inclusive processes of co-learning. The Living Lab can help facilitate learning about the ‘whats’ (what are/should we do?) and the ‘whys’ (why are/should we be doing it?) as different contexts and the needs of the stakeholders determine. While there is a dedicated ‘official’ facilitator within each Living Lab to help design learning events and provide direction and advice, the participants in the Living Labs can also ease learning and commit to designing new forms of practice with other participants.

Facilitation requires several skills, not least the ability to develop trusting relationships with other participants, an understanding of group dynamics, good communication skills and a willingness to engage with other peoples’ framing of situations, interests and concerns. In turn, this requires the use of a range of participative techniques and tools, such as diagramming, that support these skills and promote learning and insights.

We talked in Session 3 about the factors we used when choosing the six Living labs. We have also talked a bit about the overall approach we adopted, which is in part captured by the word cloud from when we started (Figure 5.1). Interestingly, facilitation does not appear but monitoring (and evaluation) does.

And yet from the outset we established two key roles for each Living Lab – an official Lab facilitator (as Kevin Collins mentions) and a Lab monitor. This division of roles is seen as important in allowing each to focus on different aspects of the ‘health’ of the Living Lab but at the same time work as a team. Monitoring and evaluation is the topic for Session 6, but it is important that facilitation, the topic of this session, is seen as being intimately linked to monitoring and evaluation.

Some information on facilitation skills and using role play to practise them is covered in the AgriLink Living Lab Toolbox, but the way that facilitators worked in AgriLink covered three main areas:

| 1. identifying and engaging with stakeholders |

| 2. planning meetings and other events involving stakeholders |

| 3. facilitating events involving stakeholders. |

While we have labelled them as distinct areas, they do overlap considerably. We will look at how we approached each of these areas in turn, drawing on the AgriLink Living Lab Toolbox.

Identifying and engaging stakeholders – stakeholder analysis

A stakeholder is a person who has a vested interest in the outcome of your project. In other words, anyone affected by or anyone with influence on what you do.

There are many ways of identifying and categorising stakeholders, and what we present here is the approach we used. This is also a summary of what we did, and a longer explanation is given in the section on Dialogue with stakeholders in the AgriLink Living Lab Toolbox. If you are more deeply interested in stakeholding in agriculture then there is an even longer document Influence without Power: Stakeholder Management in Practice from an Agrilink partner, Wageningen University and Research.

First, we considered what is the most effective way of involving stakeholders and came up with four ways. There are many symptoms of disastrous meetings and they can be described in different ways, but our list of symptoms was:

Consult – ask for views, ideas, etc. |

Inform – present activities and results |

Involve – take part in the project |

Ownership – it becomes their project. |

Second, we thought about how stakeholders might behave and from the literature identified three main types – blockers, movers and floaters. There are many symptoms of disastrous meetings, and they can be described in different ways, but our list of symptoms was:

Blockers would oppose the interests of the Living Lab and have good reasons not to change as they will have other priorities. There are two types: open and covert blockers. |

Movers interests would correspond to the intended changes being investigated and be in favour of it. |

Floaters would have no clear interest in the change and would wait to see what happens and join with either the movers or blockers. |

The strategy we devised to engage with stakeholders had the following elements:

Find out the interests of the stakeholder that explains their position. |

Inform them about the Living Lab proposal and find out their position and interests. |

This could change over time:

|

Make coalitions with the movers. |

Confront blockers with your success supported by movers. |

Seduce and convince floaters. |

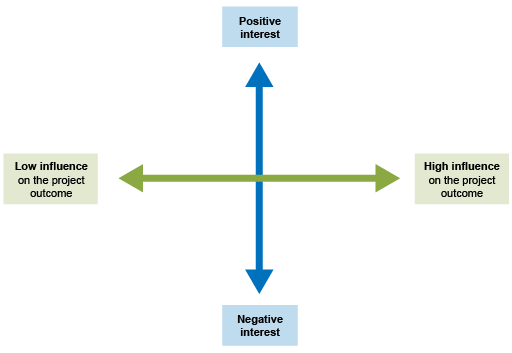

One way to evaluate the potential impact of stakeholders on the Living Lab is to use a matrix of interest versus influence as shown in Figure 5.2 (a more practical version to use is in the Toolbox).

Remember that influence is not necessarily about money or power but about commitment to the Living Lab in both the short and the long term. And interests can be positive, negative or even indifferent. The challenge is to create movement and momentum within stakeholders such that you increase the positive interests and reduce the negative interests.

Another way to capture your evaluation of stakeholders is to set out their interest and type of behaviour along with how you plan to handle them in a table like that shown in Table 5.1. Of course, that is not the only things you will have to plan.

Table 5.1 Example planning table for managing stakeholders

Stakeholder Name Organisation | Interest | Blocker Floater | Your strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | ||||

| 7 | ||||

| 8 | ||||

| 9 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 11 | ||||

| 12 | ||||

| 13 | ||||

| 14 | ||||

| 15 | ||||

| 16 | ||||

| 17 | ||||

| 18 |

We will discuss our experiences with engaging stakeholders in more detail in Session 7 on Dos and Don’ts.

Planning meetings and other events involving stakeholders

When planning meetings or other events, there is always the prior question of what is the right time for a meeting? This will depend on many things, but first of all you need to consider the purpose (or your purpose) for holding the meeting, what the dynamics between the invitees will be and whether there are existing opportunities (a meeting is already planned). You therefore need a clear set of goals for the meeting, the invited participants know the purpose of the meeting, and you have made good preparations for how the meeting will be run and facilitated.

For our Living Labs, it was important that we understood the perspectives, interests, opinions, feelings and ideas of different parties that have a stake or influence on the subject of the Living Lab (this equates with the first phase of design thinking – the empathise phase). This was done by having an initial dialogue with them, both to build rapport and to start building a shared understanding of what the Living Lab is about.

The dialogue consisted of two parts, the first being the identification of the main stakeholders as discussed above, followed by individual interviews with (representatives of) the main stakeholders involved in the sustainability challenge. The interviews aimed to understand each stakeholder’s position in and perspective on the context of the Living Lab and their ideas on the challenges for providers of new innovation support services,which was done by exploring the following points:

| Formal role of the stakeholder |

| Institutional context |

| Their relationship with other stakeholders and means of communication |

| Perspective on the sustainability challenge |

| Their role in the sustainability challenge |

| Stake and values in the sustainability challenge |

| Actual and potential influence on the sustainability challenge |

| Ideas for improving on the sustainability challenge |

| Perspective on the role of innovation support in the sustainability challenge and ideas for improvement |

| Interest to participate in Living Lab on sustainability challenge |

| Other actors that need to be included in the Living Lab. |

Only then was a workshop with the key stakeholders held to gain mutual understanding of different perspectives and to develop a collective view on the core challenges at hand (these workshops were designed using the concept of systemic co-inquiry where participants are invited and supported to engage together in the design of the Living Lab).

Facilitating events involving stakeholders

Organising and preparing for a meeting or event is only part of the picture. We also needed to pay attention to the likely group dynamics and use our facilitation skills to offset any disasters.

Reflective Activity 11

Reflective Activity 11

Most of us have been in meetings where things did not go well and nothing useful was achieved. Can you write down some of symptoms of a ‘bad’ meeting that you have experienced?

Answer

There are many symptoms of disastrous meetings and they can be described in different ways, but our list of symptoms was:

| One person dominates the discussion |

| No real interaction happens |

| People in the meeting don’t agree with each other |

| At the end, nobody is happy |

| People don’t show up at the meeting |

| The discussion remains superficial. |

Which tool do I use when?

This is not a straightforward question to answer as the tool to be used depends on the context, the people involved, the purpose of any event and the framework you are following. In AgriLink, we have used design thinking and systems thinking as our guiding frameworks.

The different phase of design thinking lend themselves to different tools. The empathise phase is more exploratory and so rich picturing or conversation mapping can be used to capture different perspectives. The define phase may be best covered with a spray diagram or systems map. Similarly, the key features of systems thinking are multiple perspectives (captured in a conversation map), interconnections (can be done through a spray diagram) and boundary judgements (a systems map is good for this).

The key is to plan any event well, to try and capture as much of the thinking and conversations that surround the creation of a diagram or its explanation by its creators as well as the diagram itself, and to reflect on the outcomes. These tools work best as participatory processes that are subject to reflexive monitoring and evaluation, which is what we cover in the next session.

Summary of Session 5

The Living Lab concept is an inquiry process that builds on the principles of design thinking, systems thinking and reflexive monitoring and for this to happen requires appropriate facilitation.

Each Lab is unique, and the facilitator must adjust what they do to meet the needs of the stakeholders and the purposes of the Living Lab.

Each Lab must be observed, understood and ‘tailor-made’ interventions must be designed and developed in conjunction with its many participants and stakeholders.

Meetings have to be organised and well run, making them as participatory as possible.

This uniqueness also requires reflexive monitoring, where the performance of the Lab is regularly reviewed by participants and stakeholders, and learnings identified and acted upon.

Go to Session 6: The monitoring and evaluation of Living Labs