Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 3:33 AM

Supporting Dyslexia, Inclusive Practice and Literacy

Module overview

Introduction

Module 2 Overview

Welcome to this free module, ‘An introduction to

Select here to download the Making Sense Programme Final Report

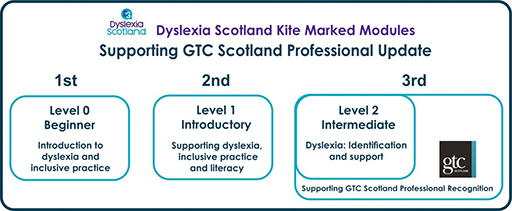

This module supports the requirement for teachers in Scotland to maintain the General Teaching Council Scotland (GTCS)’s professional standards, within which Professional Values and Personal Commitment are central.

All three modules in this collection link with the GTCS Standards 2021 Framework and focus on the areas identified below to support the professional growth of teachers in Scotland.

- Being a teacher in Scotland

- Professional knowledge and understanding

- Professional skills and abilities

- 3.1 Curriculum and pedagogy

- 3.2 The learning context

- 3.3 Professional learning

Select here for further information on the General Teaching Council Scotland’s professional learning.

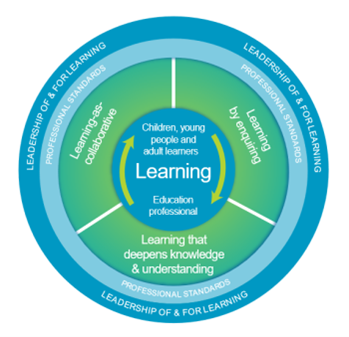

The national model of professional learning

This module also follows the national model of professional learning developed by Education Scotland which underlines that professional learning should challenge and develop thinking, knowledge, skills and understanding and should be underpinned by developing skills of enquiry and criticality.

The national model also emphasises that professional learning needs to be interactive, reflective and involve learning with and from others. It is important when considering how to study the module that the above principles are taken into consideration.

Further information on the national model of professional learning is available on the National Improvement Hub.

Learning outcomes

Module 1, ‘Introduction to Dyslexia and Inclusive Practice’, focused on what dyslexia is, its impact and how it can be supported within an inclusive school community. It achieved this by developing an awareness and understanding of:

- The education context in Scotland and the national agenda

- What dyslexia is and its impact

- Dyslexia and inclusive practice

- Effective communication

- How dyslexia is identified

- Information and practical support strategies

Module 2 aims to further support your understanding of dyslexia, inclusive practice and literacy development.

You will achieve this by developing a deeper knowledge and understanding of:

- Dyslexia and inclusive practice within the Scottish context of education, equality and equity

- Dyslexia and identification using a structured framework

- Dyslexia, co-occurring additional support needs and inclusive practice

- The importance of effective communication

- Support strategies

How you can study this module

We have provided downloadable alternative formats of this module. You can find these on the first page of each section. Please note that the module must be completed online. If you work through all of the content in this module, tackle the formative quizzes and pass the end-of-module quiz you will be awarded with a digital badge to recognise your learning.

This module can be studied sequentially, or the material can be used as a reference guide with sections explored in any order. If studied as a module, the core content should take around 3 hours to work through. Section 1 is the longest section and will take about half of the total study time.

You can study at your own pace. However, as you work through the module, think not only about your role but also that of other partners and colleagues you work with. You might find it helpful to form an informal study group with colleagues and use some of the activities as a basis for group discussion.

As with Module 1, a Reflective Log is available to download for you to evidence your professional enquiry and learning. The Reflective Log can also be used for collegiate discussions and will support Annual Reviews and GTCS Professional Update which all registered teachers in Scotland are required to maintain. It can also contribute to an application for GTCS Professional Recognition.

At the start of this module, you should complete the self- evaluation template within the Reflective Log and reflect on this again at the end of the module.

Downloadable files within this module.

Throughout this module there are files which you need to download to help you engage with the activities and others which have been included to support further professional knowledge and understanding of dyslexia and inclusive practice.

The above image of a white arrow pointing down and the text ‘You will need to download this file’ lets you know when you must download the file to engage in the activities.

The above image of a grey book lets you know when the download or link is for you to engage in further reading if you wish to.

We have also provided downloadable alternative formats of the course. You can find these on the first page of each section.

If you work through all of the content in this module, tackle the formative quizzes and pass the end-of-module quiz, you will be awarded with a digital badge to recognise your learning.

Badge information

What is a badged course?

Badges are a means of digitally recognising certain skills and achievements acquired through informal study and they are entirely optional. They do not carry any formal credit as they are not subject to the same rigour as formal assessment; nor are they proof that you have studied the full unit or course. They are a useful means of demonstrating participation and recognising informal learning.

If you'd like to learn more about badges, you will find more information on the following websites:

- Open Badges – this information is provided by IMS Global, the organisation responsible for the open badge standards.

- Digital Badges – this information is provided by HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory), a global community working to transform how we learn, and particularly making use of technology.

Gaining your badge

To gain the digital badge for this module, you will need to:

- Complete the short quizzes that you will find at the end of sections 1 and 5 of the module. These section quizzes are formative. They are really helpful in consolidating your learning but there is no pass mark.

- Complete the end-of-module quiz and achieve at least 60%.

When you have successfully achieved the completion criteria you will receive your badge for the module. You will receive an email notification that your badge has been awarded and it will appear in the My Badges area in your profile. Please note it can take up to 24 hours for a badge to be issued.

Your badge demonstrates that you have achieved the learning outcomes for the module. These outcomes are listed at the start of each section.

The digital badge does not represent formal credit or award, but rather it demonstrates successful participation in informal learning activity.

Sharing your badge

Badges awarded within OpenLearn Create can be shared via social media such as Twitter, Facebook or LinkedIn and to a badge backpack such as Badgr.

Accessing your badge

From within Supporting Dyslexia, Inclusive Practice and Literacy module:

- Go to my profile and click on Achievements. You will see the badge alongside the course title.

- To view the details of the badge, to download it, or to add it to a badge backpack, click on the badge and you will be taken to the Badge Information page.

You can either download this page to your computer or add the badge to your badge Backpack.

Acknowledgements

The development of this module was informed and supported by:

- Making Sense Working Group

- Education Scotland

- General Teaching Council Scotland Professional Standards

- Dyslexia Scotland

- Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit Working Group

- The Opening Educational Practices in Scotland Project

Except for third party materials and where otherwise stated in the acknowledgements section, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

Activity 1: Reflective Task

You will need to download the Reflective Log.

Select here to download this file.

In your Reflective Log, Activity 1 you should start by:

- Using a scale of 1 – 5 (1 being poor and 5 being very knowledgeable), rate your knowledge and understanding of dyslexia and inclusive practice.

- Consider and record what you hope to achieve in studying this module.

- Complete the template for the self-evaluation wheel.

How you use the Reflective Log is up to you. You can save it and work with it online or print it off and keep it up to date in hard copy.

Throughout the module you will be prompted to record your responses to activities and your reflection. The Reflective Log provides a record of your learning that you can use for professional update.

1. Scottish Education

Introduction

In this section we look at:

1.1. The Scottish context for dyslexia and inclusive practice

1.2. Legislative and policy framework

1.3. Additional support needs

1.4. Improving inclusive practice

1.5. Raising attainment, dyslexia and inclusive practice

1.6. Dyslexia and inclusive practice.

1.1. The Scottish context for dyslexia and inclusive practice

Module 1, Section 1 Recap

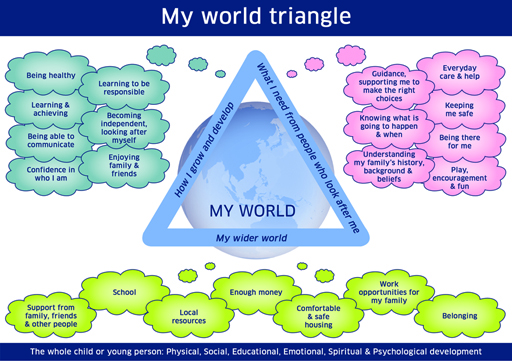

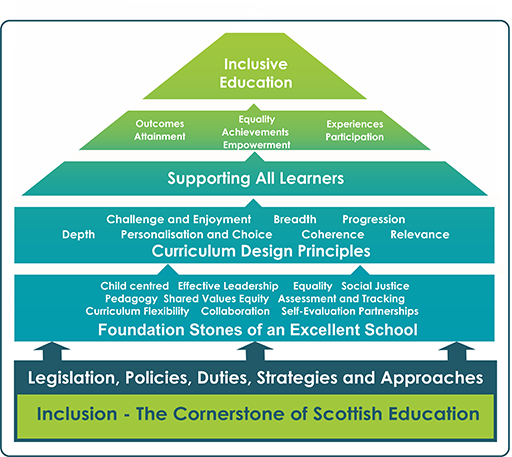

Module 1 highlighted that Scotland’s education system is designed to be an inclusive one for all children and young people in Scottish schools with or without additional support needs. Our ‘needs led’ system places the learner at the centre and the provision of support is not dependent upon a formal label or identification of need such as dyslexia, autism or a physical disability.

The legislative and policy framework places duties and expectations on schools and local authorities to ensure that they deliver an inclusive education and do not discriminate against those with protected characteristics.

The 2014 Education Scotland report Making Sense: Education for Children and Young People with Dyslexia in Scotland was the outcome of an independent review of education for children and young people who have dyslexia. It was carried out on behalf of the Scottish Government. The report highlighted 5 interlinking recommendations to improve the outcomes of learners with dyslexia, all of which the Scottish Government’s response supported. The Making Sense Working Group is working with stakeholders to support the implementation of the review’s recommendations.

Scotland’s ‘child-centred needs led’ education system has been designed to ensure that the provision of support for a child or young person is not dependent upon them receiving a formal label or identification of need such as autism, dyslexia or a physical disability.

The Scottish vision for inclusive education, which applies to all settings and for all children and young people, is set out below:

‘Inclusive education in Scotland starts from the belief that education is a human right and the foundation for a more just society. An inclusive approach which recognises diversity and holds the ambition that all children and young people are enabled to achieve to their fullest potential is the cornerstone to achieve equity and excellence in education for all of our children and young people.’

Children’s rights and entitlements are fundamental to Scotland’s approaches to inclusive education. It is supported by the legislative framework and key policy drivers including the Getting it right for every child approach, Curriculum for Excellence and the Framework for Professional Standards for teachers. These are underpinned by a set of values aligned to social justice and commitment to inclusive education. This means that inclusive education should be the heart of all areas of educational planning. However UNESCO highlight:

‘The central message is simple: every learner matters and matters equally. The complexity arises, however, when we try to put this message into practice. Implementing this message will likely require changes in thinking and practice at every level of an education system, from classroom teachers and others who provide educational experiences directly, to those responsible for national policy’.

Despite the internationally recognised inclusive legislation and policy framework that is in place to support Scottish education, ensuring inclusion and equality for all learners has been, and continues to be, a complex process. The 2020 independent review ‘Support for Learning: All our Children and All their Potential’ stated

‘There is no fundamental deficit in the principle and policy intention of the Additional Support for Learning legislation and the substantial guidance accompanying it. The challenge is in translating that intention into practice for all our children and young people who face different barriers to their learning across a range of different home and learning environments’.

Select here to download the Summary publication of ‘Support for Learning: All our Children and All their Potential’

Activity 2

In your Reflective Log, note down some of the factors which you feel contribute towards the complex process of ensuring inclusion and equity for all learners.

Click ‘Reveal discussion’ to see some contributing factors which we thought of. Do note that this list is not exhaustive.

Discussion

Local authority, school/establishment/ management and practitioners’ understanding of:

- legislative requirements and policy drivers

- their duties, values and standards of their professional body, for example the GTCS standards for registration

- appropriate planning and implementation for curriculum accessibility and flexibility when this is required

- Local authority/school/establishment ethos supporting inclusion and equality

- Opportunities for children and young people to actively participate and share their views

- Partnership working

- Effective self-evaluation and reflection

- Wider school community participation

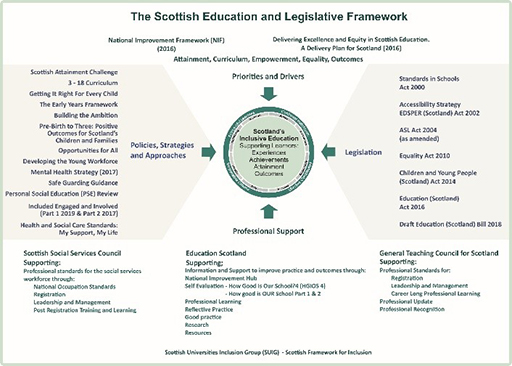

1.2. Legislative and policy framework

Module 1: Section 1.1 provided an overview of the Scottish context for education and inclusive practice, highlighting national agendas, legislation and guidance within which local authorities, teachers and other educators work (Refresh your memory of Module 1: Section 1.1).

Some of the main Acts that supports inclusion and equality in education are highlighted below and explained in further detail in this section:

- Disability Strategies and Pupils’ Educational Records (2002);

- Additional Support for Learning (Scotland) Act 2004 (as amended 2009);

- Equality Act (2010);

- Children and Young People Act (2014); and

- Education (Scotland) (2016).

Figure 1 provides further details on some specific legislation and policies that promote and support inclusion, equality and diversity within the Scottish context.

The legislation, which places duties on schools and local authorities to support and provide inclusive education for learners in Scotland, can be linked directly to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). In 2021 Scotland became the first devolved nation within the United Kingdom to enshrine the UNCRC into law. Figure 3 highlights a range of legislation that is in place to support and promote inclusion within Scottish schools and local authorities. Further details of relevant legislation can be found in Section 4 of this module.

Legislative summaries

In Module 1 you should have downloaded the summary of the Scottish educational legislative and policy framework which provides an overview of the most recent legislation and policies.

This section provides information on relevant Acts that underpin the principles of inclusion, wellbeing, equality and equity.

The Standards in Scotland’s Schools Etc. Act 2000

Every child or young person has the right and the entitlement to education, as detailed in this act. They have the right to be educated within mainstream education along with their peers and to use their rights to affect decision-making about them. Local authorities, with their partners, have a duty within the Standards in Scotland’s Schools etc. Act (2000) to ensure that ‘education is directed to the development of personality, talents and mental and physical abilities of the child or young person to their fullest potential.’ This wording deliberately reflects Article 29 1(a) of the UNCRC. This duty applies to all children, regardless of whether they require additional support to reach their full potential. The presumption in favour of providing mainstream education for all children is in place except where education in a school other than a special school would:

- not be suited to the ability or aptitude of the child;

- be incompatible with the provision of efficient education for the children with whom the child would be educated; or

- result in unreasonable public expenditure being incurred which would not ordinarily be incurred.

It will always be necessary to tailor provision to the needs of the individual child and it is recognised that there is a need to make available a range of mainstream and specialist provision, including special schools, to ensure the needs of all pupils and young people are addressed.

The Act also places education authorities under duties to provide education elsewhere than at a school where a pupil is unable to attend school due to ill health, and to make provision where a pupil is excluded from school.

The Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004 (as amended) (the ASL Act)

The ASL Act provides a framework for identifying and addressing the additional support needs of children and young people who face a barrier, or barriers, to learning. Children and young people have additional support needs when they require additional support in order to benefit from school education. Young people are those over school age but who have not yet attained the age of eighteen. The amended Act deems that all looked after children and young people have additional support needs unless the education authority has established through assessment that they do not. The Act also aims to ensure a partnership with parents/carers and collaborative working with professionals from partner services and agencies, to meet the needs of the child or young person. This module supports staff in meeting many of the learning needs of the learners in their school.

The ASL Act places duties on education authorities, requires certain other agencies to provide help where this is requested and provides parents and young people with certain rights.

Education authorities are required to identify the additional support needs of each child or young person for whose school education they are responsible. The Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004 and amendments made in 2009 provide the legal framework for assessment. However, no particular model of assessment or support is prescribed in "the Act".

The 2017 Code of Practice is also very important. This provides guidance on the implementation of the Education (ASL) (Scotland) Act, as amended in 2009. It gives a summary of the Act including clear definitions of which groups of learners are covered by the Act and what constitutes additional support needs. The duties under the terms of the Act on education authorities and other agencies with respect to supporting children‘s and young people‘s learning are set out. Examples of best practice are provided with reference to the Getting it right for every child approach (often referred to as GIRFEC) and Curriculum for Excellence framework. It is designed to help schools, parents and others understand the Act and support its implementation.

The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act (2014)

The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act (2014) places a duty on local authorities and schools to ensure the wellbeing of children and young people is safeguarded, supported and promoted. This has been an important recent change to our range of inclusive education legislation because the experience of the child or young person and the extent to which they feel included impacts on their wellbeing. The voice of the child or young person is essential in understanding their needs and ensuring their wellbeing is safeguarded, supported and promoted. Fostering strong relationships between staff and children and young people is essential to this practice.

The Getting It right for every child approach has been national policy since 2010 and is now defined in statute in the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act (2014). The Act aims to strengthen children’s rights and improve and expand services that support children and families, including looked after children. Its purpose is to ensure an inter-agency approach across education, health and social work to improve outcomes for children and young people.

It helps practitioners focus on what makes a positive difference through developing a shared understanding of wellbeing. It requires public services to work together to design, plan and deliver services for children and young people. This means services taking a collaborative approach to assessing needs and agreeing actions and outcomes to best support the child. Children and families are at the centre of the process. Agencies should work together to support streamlining of planning, assessment and decision-making so that the child gets the right help at the right time.

Most children get all the support and help they need from their parent(s), wider family and local community, in partnership with services like health and education. Where extra support is needed, the Getting it right for every child approach aims to make that support easy to access, with the child at the centre. It is for all children and young people because it is impossible to predict if or when they might need extra support.

Education (Scotland) Act (2016)

The Act introduces measures to improve Scottish education and reduce pupils’ inequality of outcomes. The Act includes provisions for strategic planning in order to consider socio-economic barriers to learning. The rights of children aged 12 and over, with capacity, are extended under the Additional Support for Learning Act. Children who are able to can also exercise their rights, on their own behalf, to affect decision-making about them. Also included within the Act are provisions on widening access to Gaelic medium education and streamlining of the process of making a complaint to Scottish Ministers. The Act also introduces the National Improvement Framework (NIF) and amendments to the Standards in Scotland’s Schools etc. Act 2000, the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004, the Education (Scotland) Act 1980 and the Welfare Reform Act 2007.

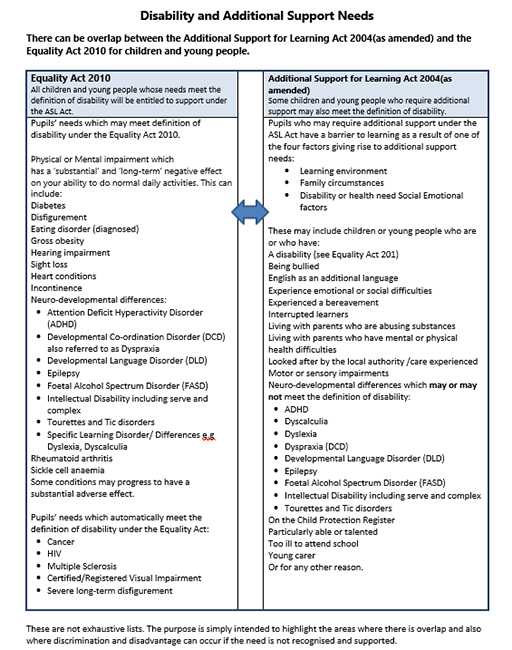

Equality and disability

It is helpful to understand what the term disability means and to appreciate the sensitivity of the term and the range of associated feelings that learners and families may have. For example, some people are very clear that they do not wish to be viewed as disabled, even if they may meet the criteria highlighted below.

A person has a disability for the purposes of the 2010 Equality Act if he or she has a physical or mental impairment and the impairment has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on his or her ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

This means that, in general:

- the person must have an impairment that is either physical or mental;

- the impairment must have adverse effects which are substantial;

- the substantial adverse effects must be long-term; and

- the long-term substantial adverse effects must be effects on normal day-to-day activities.

All of the factors above must be considered when determining whether a person is disabled.

Disability models

There are a number of ‘models’ of disability which have been defined over recent years. The two which are most frequently discussed and commonly used are the ‘social’ and the ‘medical’ models of disability; other models have evolved and developed from these two models.

Activity 3

Watch these animations which illustrate the social model of disability.

The Social model of disability and the Scottish context for education support the vision for inclusion in Scotland for all our learners - both disabled and non-disabled. Anticipatory thought is given to how disabled people can participate in activities on an equal footing with non-disabled people. Certain adjustments are made, even where this involves time or money, to ensure that disabled people are not excluded.

Please note that education staff in Scottish educational establishments do not assess and determine if a learner has a disability. This is usually done by health colleagues and should be in partnership with the family and the educational setting.

The duties of the Equality Act 2010 (commenced 1 October 2010) require responsible bodies to actively deal with inequality, and to prevent direct disability discrimination, indirect disability discrimination and discrimination arising from disability and harassment or victimisation of pupils on the basis, or a perceived basis, of protected characteristics, including disability. The provisions include:

- Prospective pupils

- Pupils at the school

- In some limited circumstances, former pupils

In addition, under the Equality Act 2010, responsible bodies have a duty to make reasonable adjustments for disabled pupils and provide auxiliary aids and services. The duty is ‘to take such steps as it is reasonable to have to take to avoid the substantial disadvantage’ to a disabled person caused by a provision, criterion or practice applied by or on behalf of a school or by the absence of an auxiliary aid or service (commenced 1 September 2012).

Further, under the Education (Disability Strategies and Pupils' Educational Records) (Scotland) Act 2002, responsible bodies have duties to develop and publish accessibility strategies to increase pupils’ access to the curriculum, access to the physical environment of schools and to improve communication with pupils with disabilities.

Education authorities and other agencies also have duties under the (Education Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004 (as amended) to identify, provide for and review the additional support needs of their pupils, including those with disabilities. The provision made to support a pupil with an additional support need arising from a disability may include auxiliary aids and services, such as communication tools and support staff.

Education authorities can ask other agencies (including social work services, health boards and Skills Development Scotland) for help in carrying out their duties under the Act. Other agencies must respond to the request within a specific timescale (there are exceptions to these timescales).

Figure 3 highlights the overlaps which can occur between the two Acts concerning disability and additional support needs. Please note that the lists are not exhaustive.

Activity 4 Reflective questions for professional dialogue with colleagues

The following questions can be used when engaging in professional dialogue during professional learning opportunities and discussions with colleagues. The outcomes from these discussions can support planning for professional learning opportunities and improvement plans.

You can collate the responses in your Reflective Log. Select here to download a discussion sheet if required.

- Why does inclusion matter?

- How can the legislation and policies within Scottish education be supported into practice?

Activity 5 Disability quiz

You should now take the Activity 5 quiz.

1.3. Additional support needs

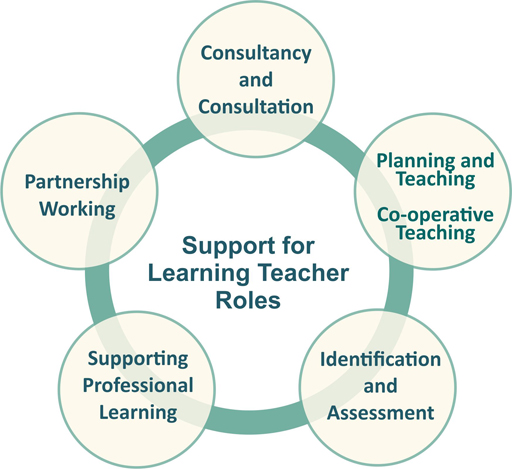

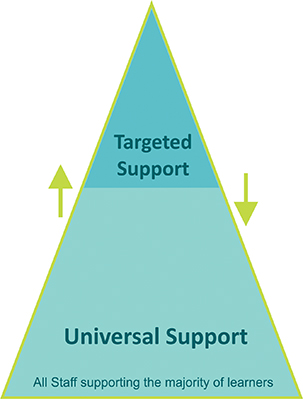

Legislation is premised on support for all learners beginning within the classroom. It is provided by the classroom teacher who holds the main responsibility for nurturing, educating and meeting the needs of all pupils in their class and, working in partnership with support staff, to plan, deliver and review curriculum programmes. Support for children and young people with dyslexia as well as those who experience literacy difficulties and other additional support needs is achieved through universal support within the staged levels of intervention. This is discussed in further detail in Section 4.

In Scotland pupils who may require additional support under the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004, as amended, have a barrier to learning as a result of one or more of the four factors giving rise to additional support needs:

- Learning environment

- Family circumstances

- Disability or health need

- Social and emotional factors

‘Additional Support Needs’ is the standard terminology used in Scotland when children and young people need more – or different - support to what is normally provided in schools or pre-schools to children of the same age. Additional support is a broad and inclusive term which applies to children or young people who, for whatever reason, require additional support, long or short term, in order to help them make the most of their school education and to be included fully in their learning. The term ‘additional support needs’ covers a wide range of factors and children or young people may require additional support for a variety of reasons.

The 2020 Independent Review of additional support for learning implementation report highlighted the interconnection between the factors which give rise to additional support needs and that they are

‘not mutually exclusive. This Review heard about increasing numbers of children and young people where issues due to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are compounded by social, emotional, behavioural problems linked to poverty and inequality’.

It is highly likely that all educational staff will work with and support learners with dyslexia or literacy difficulties at some stage. With this in mind it is important for all staff to have an awareness of their professional duties and legislation with regards to inclusion and an understanding of how to support dyslexia.

Activity 6 Revealed task

Think about your understanding of additional support needs and why children and young people may need some additional support. You may choose to take notes in your Reflective Log.

Click ‘Reveal discussion’ to see a list which highlights that children or young people may require additional support for a variety of reasons. Please note that this list in not exhaustive.

Discussion

These may include those who:

- Have motor or sensory impairment

- Are being bullied

- Are particularly able or talented

- Have experienced a bereavement

- Are interrupted learners

- Have a learning disability

- Are looked after by the local authority

- Have a learning difficulty, such as dyslexia

- Are living with parents who are abusing substances

- Are living with parents who have mental health problems

- Have English as an additional language

- Are not attending school regularly

- Have emotional or social difficulties

- Are on the child protection register

- Are young carers

Or any other reason.

Activity 7

The Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004, as amended, states that a barrier to learning results from one or more of the factors giving rise to additional support needs, otherwise learning is inhibited.

What are the factors which give rise to additional support needs?

Discussion

Options:

Learning environment

Living environment

Family circumstances

Financial difficulties

A disability or health need

A disability

A health need

Social and emotional needs

Social needs

Emotional needs

Social deprivation

Learning activities

Play spaces

1.4. Improving inclusive practice

Improving inclusive practice will support schools and local authorities to meet the needs of their learners, national and local priorities.

The Scotland’s Delivery Plan builds on work contained in the National Improvement Framework and the recommendations of the 2016 ‘Improving Schools in Scotland: An OECD Perspective’. The National Improvement Framework, published in January 2016 and updated in 2019, sets out a vision based on achieving excellence and equity for all, regardless of pupils' social background and circumstances. It sets out four priority areas for change highlighted below, which provide a shared focus for all partners to work together to make that vision a reality by addressing the six drivers of the National Improvement Framework, which are so critical to delivery:

- To improve attainment for all, particularly in literacy and numeracy

- To improve the learning progress of every child, by reducing inequality in education

- To improve children and young people’s health and wellbeing

- To improve employability skills and sustained positive school leaver destinations for all young people.

‘Delivering Excellence and Equity in Scottish Education - A delivery plan for Scotland sets how the Scottish Government’ will work with partners to deliver excellence and equity for every child in education in Scotland through a programme for delivery with a focus on action around three core aims:

- Closing the attainment gap

- Ensuring we have a curriculum that delivers for our children and teachers; and

- Empowering our teachers, schools and communities to deliver for children and young people.

The delivery plan followed engagement with a number of key education partners at an education summit focussing on raising attainment. The plan is also closely aligned with the improvement drivers outlined in the National Improvement Framework.

Select here for further information on the National Improvement Plan

Select here for further information on ‘Delivering Excellence and Equity in Scottish Education - A delivery plan for Scotland’

1.5. Raising attainment, dyslexia and inclusive practice

The Scottish Government’s vision is that Scotland should be the best place to go to school. “We want each child to enjoy an education that encourages them to be the most successful they can be and provides them with a full passport to future opportunity. To achieve this, we need to raise attainment consistently and for all our children and young people, and progressively reduce inequity in educational outcomes”.

The aims of the 2014 Making Sense report’s recommendations are consistent with national key aims for the National Improvement Framework, Scotland’s Delivery plan and Attainment Challenge Programme.

http://www.gov.scot/ Topics/ Education/ Schools/ Raisingeducationalattainment

To achieve the core aims of the National Improvement Framework and Scotland’s Delivery plan, an understanding of and a focus on additional support needs must be incorporated within schools and local authority planning and practice at the earliest stage and not perceived to be an area that can be incorporated only if needed. This approach will support timely and cost-effective planning which focuses on the national agenda and aims.

Activity 8

1. Reflective questions for professional dialogue with colleagues

The following questions can be used when engaging in professional dialogue during professional learning opportunities and discussions with colleagues. The outcomes from these discussions can support planning for professional learning opportunities and improvement plans.

You can collate the responses in your Reflective Log. Click to 'download a discussion sheet if required.

- How well does inclusive education ensure improved outcomes for children and young people with dyslexia?

- How effectively does the provision of education support and secure improved achievement and attainment for children and young people with dyslexia and with literacy difficulties?

2. Reflections on your practice

In your Reflective Log consider how you have supported a learner with dyslexia to raise their attainment

- What have I done?

- How do I know attainment was improved?

- What made the difference?

- How can I build on this learning to support more learners?

1.6. Dyslexia and inclusive practice

Module 1, Section 3 Recap

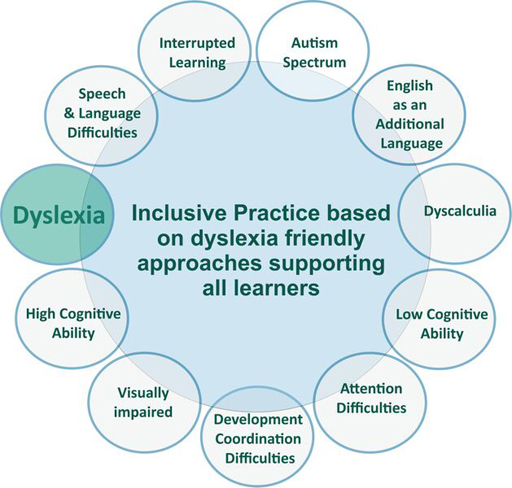

Dyslexia friendly approaches to learning and teaching support child-centred inclusive practice.

What are Dyslexia Friendly Schools?

Neil Mackay developed the ‘Dyslexia Friendly Schools’ concept in 1998. The key aims of Dyslexia Friendly Schools were to enhance the impact of learning and teaching on the child in the classroom and to ensure that teaching was multi-sensory and benefited all children, not just those with dyslexia. The approach has developed over the years and is inclusive and holistic, reflecting current research on effective positive learning for children with literacy difficulties.

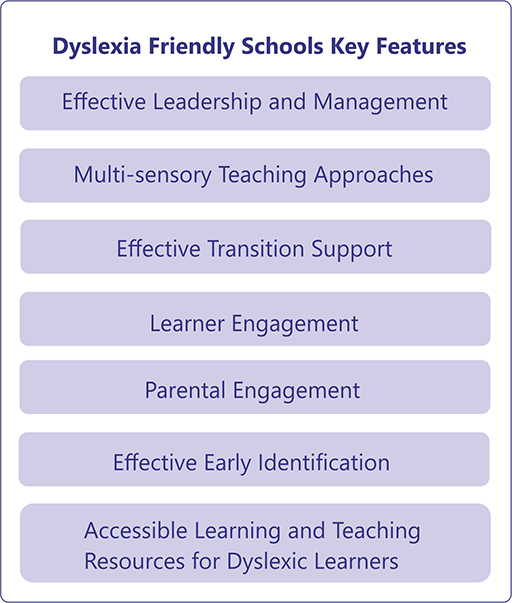

Key features of Dyslexia Friendly Schools are:

- Effective leadership and management

- Multi-sensory teaching approaches

- Effective early identification

- Effective transition support

- Learner engagement

- Parental engagement

- Learning and teaching resources which can accessed by dyslexic learners

What is Dyslexia Friendly Practice?

Dyslexia Friendly Practice is an important element of inclusive practice. It includes approaches to learning and teaching which are child-centred and also support inclusive practice for all learners. A number of initiatives are supporting the development, recognition and implementation of inclusive practice within Scottish education with the aim of improving the educational experiences and outcomes of learners who are dyslexic. These are:

- Current education policies and legislation which support inclusion and equality legislation

- Professional duties e.g. General Teaching Council for Scotland

- Self-evaluation frameworks to support improvement

- Acceptance that dyslexia exists and awareness of the neurological, genetic and environmental factors which impact on dyslexia

- Availability of a free national online resource, the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit, which supports inclusive practice

- Improved understanding of an “holistic/collaborative” assessment for dyslexia

- The 2014 ‘Making Sense Review’ recommendations – Improving outcomes for dyslexic learners

- Improving understanding of links between effective support for dyslexia and inclusive practice for all learners.

It is the responsibility of schools and their partners to bring the experiences and outcomes together and apply these entitlements to produce programmes for learning across a broad and inclusive curriculum.

Every child and young person is entitled to expect their education to provide them with:

- A curriculum which is coherent from 3 to 18

- A broad general education, including well planned experiences and outcomes across all the curriculum areas from early years through to S3

- A senior phase of education after S3 which provides opportunities to obtain qualifications as well as to continue to develop the four capacities

- Opportunities to develop skills for learning, skills for life and skills for work (including career planning skills) with a continuous focus on literacy, numeracy and health and wellbeing

- Personal support to enable them to gain as much as possible from the opportunities which Curriculum for Excellence can provide

- Support in moving into positive and sustained destinations beyond school.

Activity 9 Reflective practice task

1. In your Reflective Log, consider:

- What does inclusive practice mean for you?

- What does inclusive practice mean for your learners?

- What have you done to make your teaching practice inclusive?

2. Complete the following table to describe the current practice in your class or department. Identify if any actions can be taken to support improvements. (A copy of this table is in your Reflective Log)

| Key features of Dyslexia Friendly schools | In my class/department this means | Actions |

| Effective leadership and management | ||

| Multi-sensory teaching approaches | ||

| Effective early identification | ||

| Effective transition support | ||

| Learner engagement | ||

| Parental engagement | ||

| Learning and teaching resources which can be accessed by dyslexic learners |

Inclusive practice is about meeting the needs of all learners, putting the learner at the centre of the curriculum and ensuring that barriers are removed. This will enable them to:

- Participate and learn to the best of their ability

- Gain as much as possible from the opportunities which Curriculum for Excellence can provide

- Move into a positive and sustained post school destination.

Activity 10

Consider the aims of inclusive practice listed above.

What do you feel they can/should look like in practice?

Note down your thoughts within your Reflective Log. Click ‘Reveal discussion’ to see an example of each.

- Participate and learn to the best of their ability.

Consider what can this look like?

Discussion

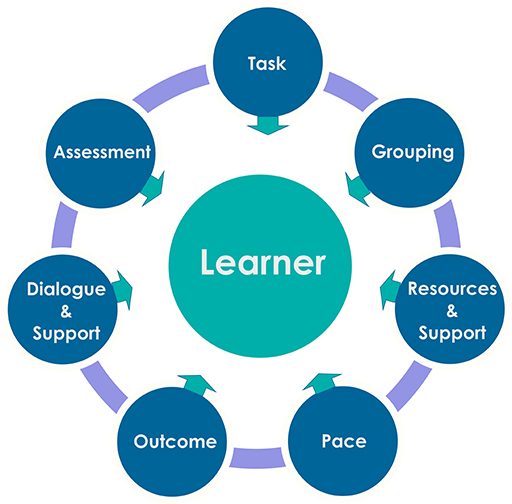

An example could be that learners are engaging in learning activities and experiences which match their cognitive ability and provide challenge and interest. To support this, an understanding of the learners’ profile is required to plan appropriate learning and teaching activities.

- Gain as much as possible from the opportunities which Curriculum for Excellence can provide

Consider what can this look like?

Discussion

An example could be that the school curriculum is flexible and personalised to meet the needs of learners with additional support needs, ensuring that there is equity and equality in curriculum accessibility. To support this, flexibility and creativity is involved when planning and timetabling the curriculum, which includes a range of award bearing courses and vocational opportunities and experiences.

- Move into a positive and sustained destination.

Consider what can this look like?

Discussion

An example could be that the attainment levels of learners with dyslexia are in line with their peers. To support this all teachers must be involved in appropriate:

- Monitoring and tracking of learners’ progress to support early intervention

- Arrangements for assessment and tracking to provide personalised guidance and support throughout the learner journey

- Use of data to inform effective planning and support

Dyslexia and Inclusive Practice: Professional Learning Resource

A reflective and evaluative professional learning approach to improve practice and empower whole school approaches to support learners.

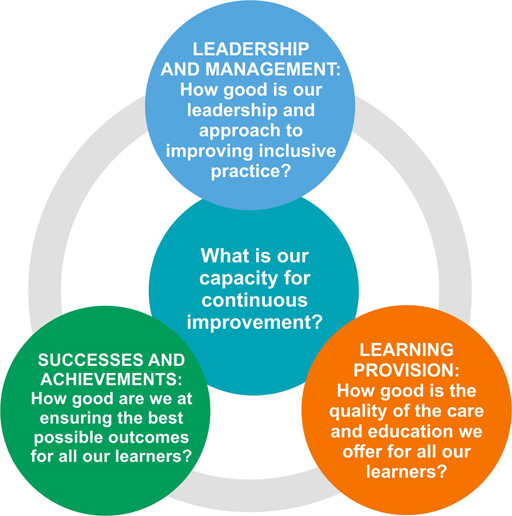

This professional learning resource focuses on eight key areas that were developed through stakeholder consultation (Figure 7), to support improvements in the outcomes for all learners including learners with dyslexia. These are very similar to the key features of Dyslexia Friendly schools in Figure 6.

This professional learning resource is one of several free resources that have been developed in response to the 2014 Education Scotland report Making Sense: Education for Children and Young People with Dyslexia in Scotland.

Developed by Education Scotland, the Making Sense Working Group and stakeholders, it aims to support practitioners, schools and local authorities to:

- Improve the quality of educational outcomes for learners with dyslexia through collaborative enquiry and effective self-evaluation

- Evidence the impact of the collaborative enquiry through evidence-based improvements

- Fulfil statutory duties

- Support professional learning on inclusive practice

- Further develop inclusive practice for all learners within the school community.

- Build on partnerships within the Regional Improvement Collaboratives (RICs), developing opportunities to share practice and reduce duplication of resource development.

The level of awareness and readiness for change will vary across schools and local authorities and this resource can be used to focus on specific key areas for improvement or to contribute to whole school inclusive practice.

Section 3, Supporting learners and families provides you with an opportunity to explore the Scottish curriculum and inclusion.

Activity 11 Reflective Log

- Have we successfully established an inclusive school community? How do we know – what is the evidence and impact?

- Are all our school policies and planning methods inclusive – do they fulfil the statutory and professional duties?

- How do we consult with and involve all stakeholders in the self-evaluation of inclusive practice and support for dyslexia?

Supporting improvement

‘How Good Is Our School 4’ (HGIOS 4) is a resource to support improvement through self-evaluation and inclusion and is embedded across all the themes and quality indicators.

The table below highlights how the reflective questions can support school communities evaluate their inclusive practice and identify areas for improvement.

Activity 12

a.

1.1 Self-evaluation for self-improvement

b.

1.2 Leadership of learning

c.

1.3 Leadership of change

d.

1.4 Leadership and management of staff

e.

1.5 Management of resources to promote equity

f.

2.1 Safeguarding and child protection

g.

2.2 Curriculum

h.

2.3 Learning, teaching and assessment

i.

2.4 Personalised support

j.

2.5 Family learning

k.

2.6 Transitions

l.

2.7 Partnerships

m.

3.1 Ensuring wellbeing, equality and inclusion

n.

3.2 Raising attainment and achievement

o.

3.3 Increasing creativity and employability

The correct answers are a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n and o.

Answer

Inclusive practice is featured across all 3 themes and the 15 Quality Indicators within HGIOS 4.

Discussion

This self-evaluation framework is designed to promote effective self-evaluation as the first important stage in a process of achieving self-improvement. Reflecting on inclusion when evaluating practice to see what is working well and what needs to improve will support the educational experiences and outcomes for dyslexia and other additional support needs.

2. Understanding dyslexia

Introduction

In this section …

2.1. What is dyslexia?

2.2. Dyslexia and neurodiversity

2.3. The co–occurrence of dyslexia with other areas of additional support

2.4. The impact of dyslexia

2.5. Dyslexia and literacy

2.6. Language development

2.1. What is dyslexia?

Module 1, Section 2 Recap

Module 1 highlighted the 2009 Scottish Government working definition of dyslexia that was developed and agreed by the Scottish Government, Dyslexia Scotland and the Cross-Party Group on Dyslexia in the Scottish Parliament

Historical background

In 1877, Adolph Kussmaul, a German neurologist, observed characteristics of reading difficulty and described them as ‘word blindness’.

Since around the late 1880s the term ‘dyslexia’ was introduced by a German ophthalmologist, Rudolf Berliner, after he observed adults having difficulties with the written word. Both scientists highlighted the link between individuals’ difficulties with reading and visual difficulties but recognised that those difficulties did not represent the individual’s cognitive ability. Berliner developed the term ‘dyslexia’ from the Greek words.

dys = difficult, hard - Greek - δυσ (dus)

lexia = reading, word, speech - λέξις (lexis)

Dyslexia definition and identification debate

Dyslexia has been a focus of debate spanning several decades. There is a range of definitions of dyslexia available internationally reflecting the different perspectives and foci that make up the debate. For example, some may view dyslexia within the context of reading and spelling and consider dyslexia to be a ‘reading disability’ – using a medical model. Definitions are important because professional bodies and academic research can influence the direction of a definition and hence the approaches and processes which are recommended within education systems.

Module 3 will explore the area of identification in greater detail.

Select here for further reading and research on this area in the Professional Development section of the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit.

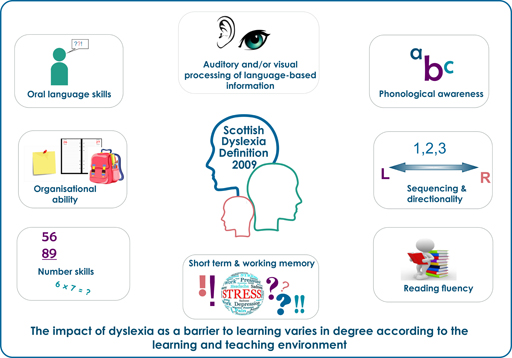

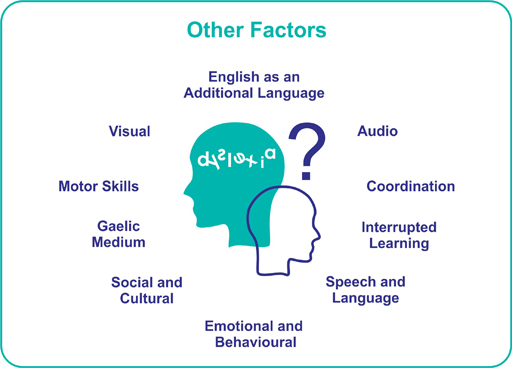

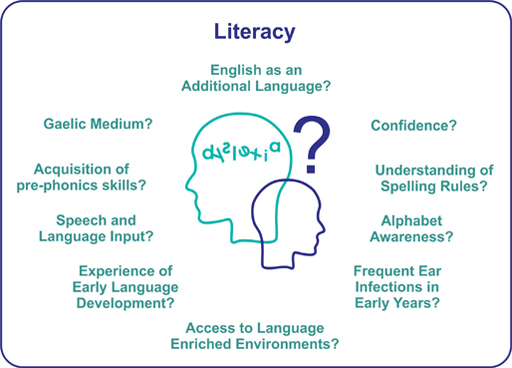

As the Scottish working definition highlights, dyslexia exists in all cultures and across the range of abilities and socio-economic backgrounds. It is not linked specifically to either low or high cognitive ability. This means that learners of all cognitive ability levels can be dyslexic. This is what differentiates it from other discrepancy models of dyslexia. When exploring if learners may have dyslexia it is important that consideration is given to a range of factors which may be creating the child’s or learner’s barriers to learning. The broad Scottish working definition of dyslexia aims to provide guidance for educational practitioners, learners, parents/carers and others that dyslexia does not only occur because of literacy difficulties, as highlighted in Figure 11. It is important, therefore, to consider the range of factors that may be contributing to the child or learner’s barriers to learning.

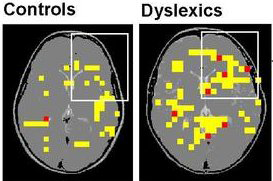

Advances in medical science have enabled the identification of dyslexia to be understood in greater detail. Neuroscience research through brain imaging has identified diversity in the brain for adolescents both with, and without dyslexia. The body of research undertaken over the past few decades by a range of academic and medical researchers, has led to an acceptance that when identified appropriately, dyslexia is a recognised learning difference and is the result of a neurological difference. It is accepted that it is not a reflection of a learner’s level of intelligence or cognitive ability. The impact of dyslexia as a barrier to learning varies in degree according to the learning and teaching environment.

Frith, in Reid and Wearmouth (2002) says that dyslexia can be defined as neuro-developmental in nature, with a biological origin and behavioural signs that extend far beyond problems with written language.

In 1999, the American Journal of Neuroradiology, provided evidence that dyslexia is neurological in nature. The interdisciplinary team of University of Washington researchers also showed that dyslexic children use nearly five times the brain area as children who are not dyslexic while performing a simple language task.

Although the images above were taken in 1999, they highlight very clearly in yellow the differences between areas of the brain which are activated while performing simple language tasks in yellow. Red indicates areas activated in two or more children. Pic: Todd Richards, University of Washington.

“The dyslexics were using 4.6 times as much area of the brain to do the same language task as the controls," said Todd Richards, co-leader of the study. "This means their brains were working a lot harder and using more energy than the normal children". "People often don't see how hard it is for dyslexic children to do a task that others do so effortlessly," added Virginia Berninger, a professor of educational psychology.

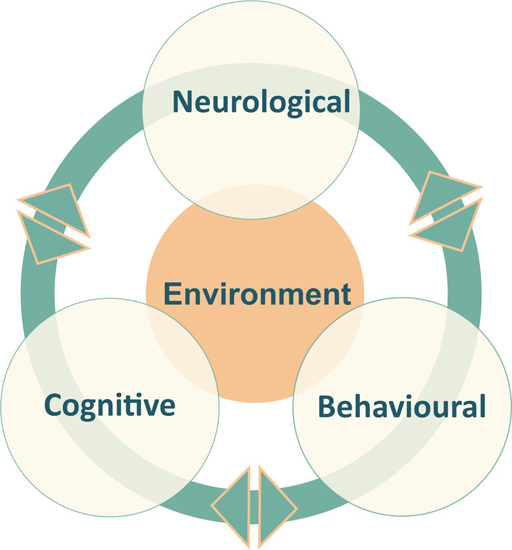

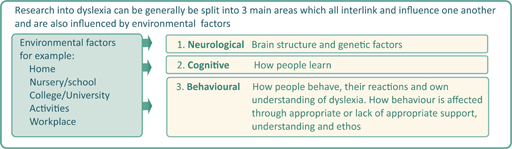

Morton & Frith (1993, 1995) developed a neutral framework for the causal modelling of developmental disorders and applied this modelling to dyslexia. The research highlights that dyslexia can be split into 3 main research areas, all of which inter-link and influence one another.

Neurological - Brain structure and genetic factors

Cognitive - How people learn

Behavioural - How people behave and their reactions to this learning difference

These are influenced by environmental interactions at all levels, which include home, nursery, schools and activities. This means that the behaviour of a child with dyslexia would change with time and in different contexts.

2.2. Dyslexia and neurodiversity

Module 1 recap

Most people are neurotypical, meaning that the brain functions and processes information in the way society expects. However, it is estimated that around 1 in 7 people (more than 15% of people in the UK) are neurodivergent, meaning that the brain functions, learns and processes information differently.

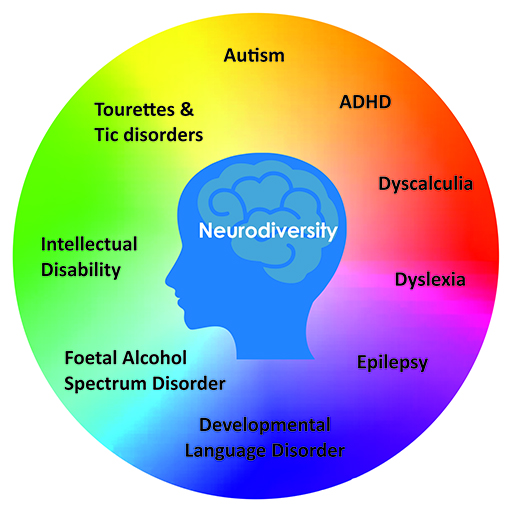

The term neurodiversity usually refers to range of specific learning differences including:

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD) also referred to as Dyspraxia

- Developmental Language Disorder (DLD)

- Epilepsy

- Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

- Intellectual disability

- Tourettes and Tic disorders

- Specific Learning Difficulties/ Differences (SpLD e.g. Dyslexia, Dyscalculia).

Section 2.4. in Module 1 highlighted the co-occurrence of dyslexia with other areas of additional support. Health professionals, industry and commerce are increasingly using the term neurodiversity and this approach supports the child-centred education system in Scotland, which also highlights the co-occurrences between specific learning differences. Research has highlighted that the child or adult who has only one area of difficulty is rare, for example work by Kaplan et al 1998.

Select here to access the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit for further information on neurodiversity and dyslexia.

2.3. The co–occurrence of dyslexia with other areas of additional support

Module 1, Section 2 Recap

The Scottish working definition of dyslexia is broad. As highlighted in Section 1.1 of this module, dyslexia does not only impact on the acquisition of literacy skills. The different characteristics involved with dyslexia are also found in a wide range of learner profiles and areas of additional support.

What is the impact of dyslexic challenges in the learning environment?

It is undoubtedly challenging to meet all the needs of learners within a teacher’s class. However, using a range of multi-sensory learning and teaching approaches within a curriculum which is planned to be inclusive and accessible does bring benefits that support and can reduce the challenge.

Figure 16 and the table below highlight some examples of co-occurrence and some support strategies

Activity 13

The table below highlights some examples of support strategies. Each strategy could be appropriate for a range of additional support needs. Consider each strategy and write down the area of ASN that would be supported by them. Click ‘Reveal answer’ to see some suggestions.

| Examples of support strategies |

| Personalised learning |

| Effective communication |

| Multi-sensory learning and teaching approaches |

| Visual time tables |

| Visual supports |

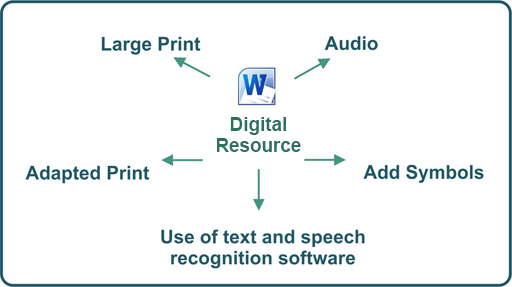

| Use of accessibility software e.g. text and speech recognition |

| Approaches to support language acquisition |

| Audio books |

| Accessible digital learning and teaching resources |

| Books for All |

| Digital exams |

Answer

| Examples of support strategies | Some examples of ASN which can be supported |

| Personalised learning | Dyslexia Autism spectrum Visually impaired English as an additional language Visual impairment |

| Effective communication | Dyslexia Autism spectrum Visually impaired English as an additional language Visual impairment |

| Multi-sensory learning and teaching approaches | Dyslexia Autism spectrum – if appropriate Visually impaired English as an additional language (Initially) |

| Visual time tables | Dyslexia Autism spectrum English as an additional language (Initially) |

| Visual supports | Dyslexia Autism spectrum Visually impaired English as an additional language Visual impairment |

| Use of accessibility software e.g. text and speech recognition | Dyslexia Autism spectrum Visually impaired |

| Approaches to support language acquisition | Dyslexia Autism spectrum English as an additional language (Initially) |

| Audio books | Dyslexia Autism spectrum English as an additional language (Initially) Visually impaired |

| Accessible digital learning and teaching resources | Dyslexia Autism spectrum Visually impaired |

| Books for All | Dyslexia Autism spectrum – if applicable Visually impaired |

| Digital exams | Dyslexia Autism spectrum Visually impaired |

2.4. The impact of dyslexia

The impact of dyslexia can manifest in a variety of ways and should not be underestimated; learners with dyslexia benefit from early identification, appropriate intervention and targeted, effective and proportionate support at the right time. How dyslexia is perceived and understood is very important. Early identification with appropriate explanations and support can support the learner and their family to understand their dyslexia and help reduce the negative impact of dyslexia. Early identification can help the learner develop their own strategies and develop their resilience which in turn helps them to approach difficulties in a more positive and effective way. When effective support and early identification are not in place, dyslexia often has a negative impact on learners, parents, families and carers who become distressed that their dependents cannot get the support they need. In both children and adults, when dyslexia is unidentified or unsupported the negative impact can be high. It can lead to children and young people losing motivation and becoming frustrated through the stress of trying to learn, not understanding what dyslexia is. They may feel that they are ‘different’ to others because they find difficulty in doing what to others are simple tasks. This can lead to acute behavioural problems both at school and at home. It may include bullying and anti-social behaviour, as well as low self-esteem and severe frustration for children and young people not reaching their potential.

The impact on adults whose dyslexia is not identified and supported can be underachievement in further education and employment. The negative effects of dyslexia on self-esteem and confidence can lead to high stress levels, damage to personal relationships, day-to-day difficulties, depression and mental health problems. There is an established link between offenders and dyslexia. It is estimated that a high percentage of prisoners have literacy difficulties which includes dyslexia.

Understanding how individuals are feeling can help school staff and parents support the learner. However, be aware that negative feelings can often be hidden or masked, and the learners may need support to help them understand their dyslexia, in order to help them build their resilience and confidence.

The following quotes are edited extracts from ‘Dyslexia and Us’, a book published by Dyslexia Scotland. The quotes are as written by the contributors. They show the profound effect dyslexia can have.

“It is good being dyslexic. When I first found out I was dyslexic I was 8 years old. Once I found out it was actually good as all the strategies to help me could be put in place, which made everything so much easier. Before I knew I was dyslexic I thought I was rubbish at lots of things.”

“I struggle to do maths. Reeding and right are hard. I forget words. I looz things. I need help.”

“I have dyslexia, my brain is different. At the unit class it is helping me with my reading because I do my reading every day. At school I couldn’t read and write but I can now. My next door nadir is my friend is the same as me and he no how I feels. At home my sister and my brother make fun of me because I can’t say words right and I get upset and cray.”

“I am an eleven year old dyslexic boy and although when I was younger dyslexia got the better of me I now see it as a gift, the power to see the world in a different dimention. As I do not have a spare, non dyslexic mind to compare the way I see the world to I cannot describe how someone like me would see things. But I can say that the mind of a dyslexic is an undoughtably creative one as proved by the almost definitely Leonardo da vinci and Picasso!”

“The relief was enormous when I found out I am dyslexic! I have a very poor short term memory, my reading is inaccurate and when I was tested for dyslexia, my spelling was at the six year old level in P7 (it’s much better now). The school turned out to be great! Once my dyslexia was exposed and my difficulties were out in the open, my teachers gave me a lot of help. Apparently my short term memory does not work like a ‘normal’ person’s, so I forget what has just been said to me – it seems to slide right out of the head. No wonder I could never find the right page!

I used to think that I would end up dropping out of school and end up stacking shelves in some supermarket – but no more. Learning that I have dyslexia has given me a whole new view of life, and I now know that I can have the same ambitions as anyone else – I may just have to take a different route to get there.”

“My oldest daughter is severely dyslexic and looking back on her schooldays reminds me how unhappy they were for her and the family. She was so frustrated by her teachers and her class mates thinking she was stupid, and consequently she was patronised by her teachers and teased by her classmates. I was either battling with her school to give her the proper support she needed, or comforting her at home, or desperately trying to find alternative things in which she could achieve some self esteem.

I always knew she wasn’t stupid so it was a relief when her dyslexia was identified. However, battles continued in the wider world – unable to learn sequences, difficulty in carrying out verbal directions from her driving instructor and often getting on the wrong bus or train because she was unable to read the notice boards. It was a triumph when she made it to university, a dream she never thought she would achieve. My daughter’s determination has been quite extraordinary. In that sense you could say that dyslexia has made her the wonderful person that she is today but it is small comfort for the years of struggling which she has endured.”

2.5. Dyslexia and literacy

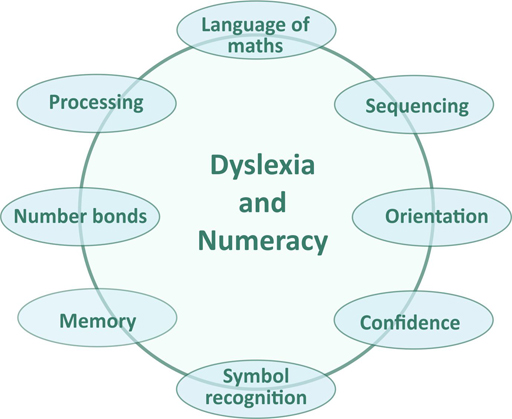

Historically dyslexia and literacy have been intrinsically linked. The early research and investigations which started in the late 1800s were carried out by individuals who believed that dyslexia was caused by visual processing difficulties, which in turn caused individuals to experience difficulties with reading. Over the years, a range of definitions have been developed in the United Kingdom and internationally. These definitions focus predominately on dyslexia being caused by difficulties experienced with literacy skills, particularly reading and spelling. It is therefore understandable that literacy is very often the first and sometimes the only area associated with dyslexia. It is important, however, to be aware that there can be a range of reasons why a child or young person is experiencing literacy difficulties which may not be due to dyslexia. It may also be that a learner may be able to read and write with the result that concerns are not raised, yet they may experience difficulties with processing, working memory and organisation which can have a significant impact on their learning.

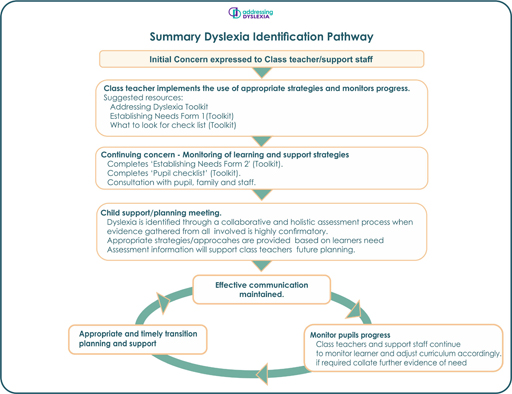

The Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit working group has developed a range of free resources which will support practitioners in need to explore, indeed rule out, possible other factors which can impact on the development of literacy skills. This can be done by using a collaborative and holistic identification pathway (such as the one available in the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit and which was highlighted within Module 1), combined with the Toolkit’s Literacy Circles which you could access and download. These resources can help those involved to explore the causal factor of the learner’s literacy difficulty and determine if it is due to dyslexia. However it is also important to remember that our education system is ‘needs led’ and that the support provided to learners is not dependent on a formal identification or label. The learner can receive the same support whether they are dyslexic or not.

Activity 14

In your Reflective Log, note down other factors which you feel can impact on the development of literacy skills.

Click ‘Reveal discussion’ to see the range of other factors which can have an impact on the development of literacy skills. Please note they are not exhaustive.

Activity 15 Reflective questions for professional dialogue with colleagues

The following questions can be used when engaging in professional dialogue during professional learning opportunities and discussions with colleagues. The outcomes from these discussions can support planning for professional learning opportunities and improvement plans. You can collate the responses in your Reflective Log. Click to 'download' a discussion sheet if required.

- How successfully do we use the most appropriate teaching methods to support dyslexic learners in acquiring the tools for reading and developing higher order comprehension skills? How well do we choose suitable tasks, activities and resources?

- Do our teaching staff have the required knowledge and understanding to teach literacy and how do we know?

2.6. Language development

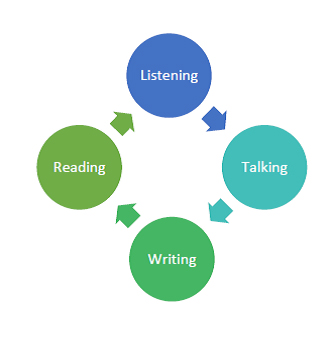

“Our ability to use language is central to our thinking, our learning and our personal development. Literacy and language unlock access to the wider curriculum and lay the foundations for communication, lifelong learning and work, contributing strongly to the development of all four capacities of Curriculum for Excellence”.

Research has highlighted the importance of positive influences in the early years in improving a child’s life chances.

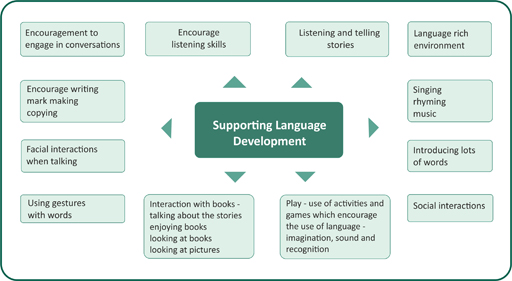

There is a strong relationship between early life experiences and how children learn. Inequalities experienced by parents and children can affect speech, language and communication development and lead to further inequalities later in life. These early learning experiences are vital in forming the building blocks from which more formal literacy learning can be developed. A literacy rich environment promotes, supports and enriches listening, talking, reading and writing. This is shown in Figure 17. This approach models high standards and sets high expectations for literacy.

The Scottish Government 2010 Literacy Action Plan highlights that literacy starts from birth and in the very early years. The home learning environment for children from birth to 3 years old has a significant impact on cognitive and language development. Parents, irrespective of socio-economic group or where they live, can make a real difference to their children's outcomes by talking to them, playing with them and ensuring they engage in different experiences. Interacting with and providing stimulating environments for young children helps to put in place the building blocks for their growth and development. Communication and engaging with books from an early age are crucial to speech and language development. Extensive research has highlighted the positive impact of reading to children in their pre-school years. Previously published ‘Growing Up in Scotland’ data has shown that children who are frequently read to in the first year of life score higher in assessments of cognitive ability at age 3-4 years old. This suggests that in the very early years the home learning environment for children from birth to 3 years old has a significant impact on cognitive and language development.

Activity 16

As children grow towards primary school age, their social, emotional, physical and educational wellbeing build upon foundations laid in earlier years and continue to be influenced by their home environment and their relationship with their parents. Before formal education can begin, a range of skills should ideally be learnt by the children. Consider what you think these are and click the ‘Reveal discussion’ button for the answer.

Discussion

Before formal education can begin, children must learn to:

- Play

- Talk

- Listen

- Understand

- Attend

Figure 18 highlights helpful approaches which can support good language development in young children. A range of resources have been developed by Allied Health Professions for example speech and language therapists to highlight the expected language developmental milestones.

Select here to access the Milestones to support learners with complex needs.

To support the development of language and numeracy skills for children in Primary 1–3, the Scottish Government is leading a campaign which focuses on key skills among children called Read, Write and Count. This campaign is aimed at encouraging and supporting parents and families in the key role they play in helping their children to read, write and count well. The approach is to incorporate reading, writing and counting into their everyday activities, such as walking around the supermarket or travelling home from school.

The campaign builds on the Scottish Government’s PlayTalk Read early years campaign and is being delivered in partnership with Education Scotland and The Scottish Book Trust over 3 years. It builds on relevant established frameworks which include Curriculum for Excellence and Raising Attainment for All and aims to tackle educational inequalities and raise attainment in early years and beyond.

For more information and resources on Read, Write, Count, visit www.readwritecount.scot.

Education Scotland have published the Primary One Literacy Assessment and Action Resource (POLAAR) that is designed to support improvement by helping Primary 1 teachers identify and assess children who are most at risk of developing later difficulties with reading and writing.

It is based on a staged intervention model of ‘observe-action-observe’, which helps identify the most effective intervention to take at classroom and child levels.

Although the POLAAR resources focus on primary one, the resources within the pack, such as the literature reviews, are helpful for practitioners working with learners at any stage who have a literacy difficulty, including those in secondary school.

Select here to access the POLAAR resources

Activity 17

To support a learner to improve their literacy skills it is essential to develop an understanding of the learner’s consolidated

- Pre and early phonological skills

- Knowledge of the alphabet, including sequencing and names and sounds of letters.

The links below will take you to free early literacy assessments on the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit and Education Scotland websites:

In your Reflective Log, record your experience of learning about these resources and the impact of them when used with learners.

Now try the Formative quiz 1 to consolidate your knowledge and understanding from this section. Completing the quizzes is part of gaining the digital badge, as explained in the module overview.

3. Supporting learners and families

Introduction

In this section we look at:

3.1. Effective communication

3.2. Support

3.3. Curriculum for Excellence Responsibility for all – health and wellbeing, literacy and numeracy

3.4. Health and wellbeing and dyslexia

3.5. Literacy and dyslexia

3.6. Numeracy and dyslexia

3.7. Transitions

3.8. Roles and responsibilities

3.1. Effective communication

For parents and carers, wondering if their child requires additional support can understandably be a worrying and anxious experience. It is extremely important when a concern is raised by a family, the learner or a member of staff that it is followed through transparently, sensitively and effectively. Developing supportive relationships between home and school is very important.

Learners with dyslexia will benefit from early identification, appropriate intervention and targeted, effective support at the right time.

Dyslexia can impact on parents, families and carers who may become distressed when they feel that their child is not receiving the support they need. In both children and adults, when dyslexia is unidentified or unsupported the negative impact can be high. Children and young people often lose motivation and become frustrated through the stress of trying to learn, not understanding what dyslexia is and feeling that they are ‘different’ to others because they find difficulty in doing what to others appear to be simple tasks. It is very important to share with families and the learner that being dyslexic can also bring positive skills. Below are some common strengths that can be experienced by individuals with dyslexia:

- Can be very creative and enjoy practical tasks

- Strong visual thinking skills e.g. seeing and thinking in 3D, visualising a structure from plans

- Good verbal skills and good social interaction

- Good at problem-solving, thinking outside the box, seeing the whole picture.

It is essential that information is shared with parents and carers so they can understand the holistic process of identification and support of dyslexia within Curriculum for Excellence. You will explore this further in Section 4, ‘Assessment and monitoring’ of this module and in Module 3. This includes information on when families choose to have an independent or private assessment for the identification of dyslexia.

Module 1, Section 1.6 Recap

Effective communication, respect and partnership working are key requirements between schools and families. They are essential in supporting appropriate and effective identification, planning and monitoring of literacy difficulties and dyslexia.

The GTCS suite of professional standards provides a framework for teachers to examine, inform and continually develop their thinking and practice. The core area of ‘Professional Values and Personal Commitment’ highlights the following as fundamental to being a teacher:

- Social justice

- Trust and respect

- Integrity

- Professional commitment

These, along with many aspects of Professional Knowledge and Understanding and Professional Skills and Abilities also articulate well with the roles and responsibilities of practitioners for effective communication with learners, parents and colleagues so that they:

- Are engaged in the holistic/collaborative identification process

- Understand what is happening, including the time scales, and are kept informed if there are changes.

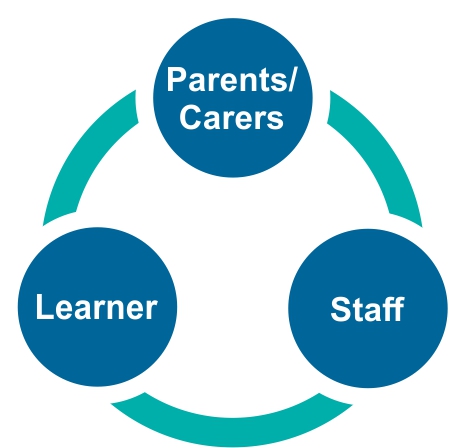

In addressing barriers to learning, the importance of effective communication should never be underestimated. Figure 19 highlights those who should, and also who may if appropriate be engaged in effective partnership working. It must be appreciated that there may be other additional people involved if required, depending on the child or young person’s individual needs. The lack of effective and transparent communication can be one of the causal factors of complaints that are raised against a school or local authority. Poor communication can result in misinformation and a misunderstanding of what support and approaches should be taken or should be in place by both staff and parents. Building strong relationships will make it easier to solve disagreements informally.

Legislation is in place to support parents, children and young people to:

- Request specific assessments which must begin within a set time frame

- Access free advocacy and mediation services

- Have access to assessments and information documented

3.2. Support

Dyslexia can be an emotional experience, which can be both positive and unfortunately negative. There are often misconceptions and misunderstanding about dyslexia from all perspectives and the issue of ‘support’ can be misinterpreted. A survey in the 2000s by a Dyslexia charity undertaken by parents highlighted that they valued the support, motivation and ethos of the school and the staff far more than physical resources such as IT equipment, one to one tuition and small group work.

Often the school is providing support in a range of ways for a learner, but has not communicated this, or the progress the learner is making, to the parents. This can lead to the perception that the school is not doing anything and does not believe in dyslexia. A short case study is provided, which focuses on sharing information with parents about their children’s progress and learning in school.

QR Codes – Sharing Learning with Parents

This year within Barshare Primary we have been developing QR codes to help us share learning with parents.

In our Supported Learning Centre and mainstream school, many of the children have communication difficulties, which means that it can be difficult for parents to see evidence of how their child is supported and the progress the child is making with the interventions in place. That’s when the Barshare Barrier Busters come into action!

Evidence of progress is documented by photographs or video and put onto a QR code. This code is sent home to parents and the learning comes to life!

Check out one of our pupils reciting his poem by scanning the QR code image below.

(If you have difficulty getting the QR code to work or if you don't have a mobile device with a QR code app installed, you can use the following URL http://qrs.ly/ yj5gu8k)

His parents recently told us,

“It allows me an insight into what my child is like at school and what he is capable of. I have also been able to share my child’s learning with extended family using the URL…..I look forward to more.”

The Collaborative and Holistic Identification Pathway is a valuable tool in the process of communication about the needs of a learner.