Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 22 February 2026, 6:13 PM

Dyslexia Identification and Support

Introduction

Module 3 overview

Welcome to this free online module, ‘Dyslexia: Identification and Support’, the third and final module from the ‘Dyslexia and Inclusive Practice’ collection. This module has been designed primarily for Support for Learning/Additional Support, Specialist teachers and local authority inclusion staff. However, anyone who has completed and passed modules 1 and 2 can also participate. The module supports the recommendations of the 2014 Education Scotland Review: ‘Making Sense: Education for Children and Young People with Dyslexia in Scotland’. The modules have been created by the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit working group, Dyslexia Scotland and Education Scotland with the support of the Opening Educational Practices in Scotland Project.

Module development

The Scottish Government is working with partners who have supported the development of free professional learning resources which you have accessed in modules 1 and 2. These resources aim to provide teachers and local authority staff with an awareness of what dyslexia is, its impact and how it can be identified.

Module 3 was developed in partnership with The Open University in Scotland. This refreshed 2021 version follows the same structure as modules 1 and 2. Copies of each module can be downloaded from the module landing pages.

Badge information

What is a badged course?

Badges are a means of digitally recognising certain skills and achievements acquired through informal study and are entirely optional. They do not carry any formal credit as they are not subject to the same rigour as formal assessment; nor are they proof that you have studied the full unit or course. They are a useful means of demonstrating participation and recognising informal learning.

If you'd like to learn more about badges, you will find more information on the following websites:

- Open Badges – this information is provided by IMS Global, the organisation responsible for the open badge standards.

- Digital Badges – this information is provided by HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory), a global community working to transform how we learn, and particularly making use of technology.

Gaining your badge

To gain the digital badge for this module, you will need to:

- Complete the short quizzes that you will find at the end of sections 1 and 5 of this module. These section quizzes are formative. They are really helpful in consolidating your learning but there is no pass mark.

- Complete the end-of-module quiz and achieve at least 60%.

When you have successfully achieved the completion criteria you will receive your badge for the module. You will receive an email notification that your badge has been awarded and it will appear in the My Badges area in your profile. Please note it can take up to 24 hours for a badge to be issued.

Your badge demonstrates that you have achieved the learning outcomes for the module. These outcomes are listed at the start of each section.

The digital badge does not represent formal credit or award, but rather it demonstrates successful participation in an informal learning activity.

Sharing your badge

Badges awarded within OpenLearn Create can be shared via social media such as Twitter, Facebook or LinkedIn and to a badge backpack such as Badgr.

Accessing your badge

From within Dyslexia: Identification and Support module:

- Go to my profile and click on achievements. You will see the badge alongside the course title.

- To view the details of the badge, to download it, or to add it to a badge backpack, click on the badge and you will be taken to the Badge Information page.

You can either download this page to your computer or add the badge to your badge Backpack.

Acknowledgements

The development of this module was informed and supported by:

- Making Sense Working Group

- Education Scotland

- General Teaching Council Scotland Professional Standards

- Dyslexia Scotland

- Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit Working Group

- The Opening Educational Practices in Scotland Project

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated in the acknowledgements section, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

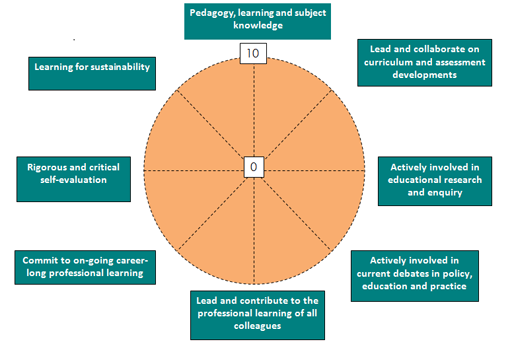

This module supports the requirement for teachers in Scotland to maintain the General Teaching Council Scotland’s (GTCS) professional standards within which Professional Values and Personal Commitment are central.

All three modules in this collection link with the GTCS Standards Framework and focus on areas identified below to support the professional growth of teachers in Scotland.

- 1 Being a Teacher in Scotland

- 2 Professional Knowledge and Understanding

- 3 Professional Skills and Abilities

- 3.1 Curriculum and Pedagogy

- 3.2 The Learning Context

- 3.3 Professional Learning

Select here for further information on the General Teaching Council Scotland’s professional learning.

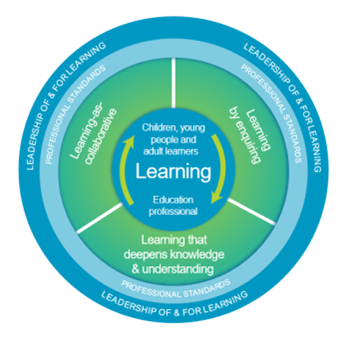

The national model of professional learning

This module also follows the national model of professional learning developed by Education Scotland which underlines that professional learning should challenge and develop thinking, knowledge, skills and understanding and should be underpinned by developing skills of enquiry and criticality.

The national model also emphasises that professional learning needs to be interactive, reflective and involve learning with and from others. It is important when considering how to study the module that the above principles are taken into consideration.

Further information on the national model of professional learning is available on the National Improvement Hub.

Pair or group work

When an activity particularly lends itself to pair or group work you will see the icon below against it.

Downloadable files within this module

Throughout this module there are files which you need to download to help you engage with the activities and others which have been included to support further professional knowledge and understanding of dyslexia and inclusive practice.

The above image of a white arrow pointing down and the text ‘you will need to download this file’ lets you know when you must download the file to engage in the activities.

The above image of a grey book lets you know when the download or link is for you to engage in further reading if you wish.

Learning outcomes

Module 2 supported your understanding of dyslexia, inclusive practice and literacy development. You developed a deeper understanding of:

- Dyslexia and inclusive practice within the Scottish context of education, equality and equity

- Dyslexia and how it is identified

- Dyslexia, co-occurring additional support needs and inclusive practice

- Effective communication

- Support strategies

By participating in the tasks for module 3, you will have a deeper understanding and experience of:

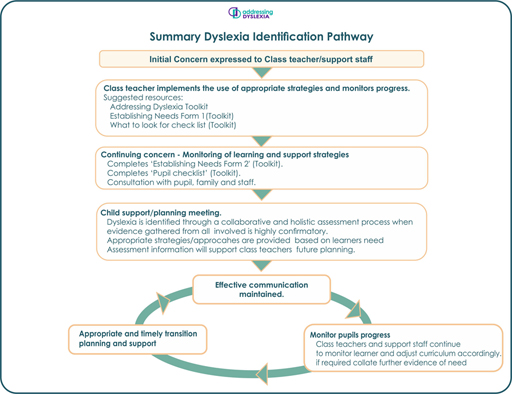

- Holistic and collaborative identification of dyslexia using the Pathway within the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit

- Appropriate support and assessment within the Scottish context

- Enabling school communities to improve the outcomes of learners with dyslexia and associated difficulties

- Supporting school communities to improve inclusive practice

- Developing learner profiles to support post-school transition

The learning outcomes for this module have a focus on supporting the wider school community. As you progress through the module it may help to develop an Action Plan and use this as a working document to support your next steps.

The activities in this module have been designed to support self-evaluation, reflective practice and professional development for you as an individual practitioner. The activities are also designed to support group work with colleagues and professional discussions with your line manager, which can include annual reviews and Professional Update.

At the start of the module, you should complete the self-evaluation task – Activity 1 - and reflect on this again at the end of the module. During the module you can test your knowledge by taking some practice quizzes. At the end of the module, you will be asked to complete an assessed quiz. If you achieve a score of at least 80% in the assessed quiz, have attempted the practice quizzes and have clicked through all the pages of the module you will earn a digital badge.

Action research task

This module provides the opportunity for you to undertake a piece of action research relating to dyslexia and inclusive practice. If you are intending to make an individual application for GTCS Professional Recognition, it is advisable that you complete this task. This task is not marked within the module and your professional decision and judgement will decide on the depth and quality of the task. Your findings and experience gained from the task will support professional dialogue and future study. When presenting your digital badge for module 3 to future employers for example, you may be asked for information on your action research task.

It may be helpful to consider the areas you have already engaged with in modules 1 and 2 and those which you will continue to work through in this module as a potential subject for the action research task.

Professional Recognition in dyslexia and inclusive Practice

Following the completion of modules 1, 2 and 3 you may choose to submit an individual application to the GTCS for Professional Recognition. Professional Recognition provides the opportunity for teachers who are fully registered with the GTCS and have completed one year of professional practice to focus on and develop their professional learning in particular areas of expertise and gain recognition for enhancing their knowledge, understanding and practice.

Applications require practitioners to demonstrate their knowledge, understanding and practice in the area they have identified.

The reflections and experiences which you have gained through the participation of the three modules will be evidenced in your Reflective Logs and have been designed to contribute to the evidence required for an application. The 5 key criteria are:

- Provide a critically informed theoretical rationale for the area of work chosen, including reference to relevant research, literature, policy and practice

- Critically examine, analyse and evaluate what impact the area of development and expertise has had on your thinking, learning and practice. Also consider the impact on learners and their learning, including extracts of analysed evidence to support this.

- Describe how you have shared your knowledge and experience with others and what impact this has had on colleagues and the wider community.

- Describe the next steps for the development of this area of expertise/accomplishment and your future professional learning

- In the light of this work, outline how the professional discussions with your line manager have shaped your thinking and practice (critical reflection on your learning and development).

Action research task and Professional Recognition

To help meet the criteria for Professional Recognition an action research task is included in Section 3. This module has been designed to be completed over an academic year and it is advisable to look at all sections of the module before choosing and completing your action research task. As you progress through the module consider potential focus areas for your task. This piece of action research will contribute to your Professional Portfolio which will include evidence of how you have met the criteria for Professional Recognition.

This portfolio should be discussed with your line manager as part of the ongoing Professional Review and Development (PRD) process. It is not necessary to send this to GTCS with your application. However, you are required to retain your portfolio for one year, as GTCS will conduct a sampling of successful applications twice a year to ensure consistency of standards as part of the assessment process.

Further details on GTCS Professional Recognition can be accessed on the GTC Scotland web page about Professional Recognition

Download an application form for GTCS Professional Recognition

Download ‘Your Professional Recognition Application: a Reflective Guidance Tool’

The following resources are available to support your action research project.

Download the Action Research Support Notes

Download an Action Research Planning Cycle Template

Download an Action Research Structure Template.

Activity 1 Reflective Log

Download the Module 3 Reflective Log

In your Reflective Log you should start by:

- Noting down the professional actions you took following the completion of module 2

- Considering and recording what you hope to achieve in studying this module

- Downloading and completing the template for the self- evaluation wheel.

Now go to Section 1, Scottish education.

1. Scottish education

Introduction

In this section we look at:

1.1. Identification within the Scottish context

1.2. Assessment/identification and legislation

1.3. Models for inclusion

1.4. Rights and participation

1.1. Identification within the Scottish Context

Modules 1 and 2 provided you with an overview of the Scottish educational context, which requires collaboration and a clear identification of learner needs.

Recap – Key messages

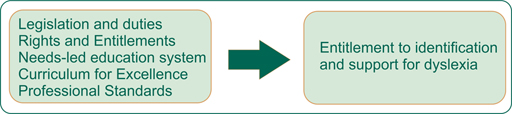

Responsible bodies are required to ensure that the individual needs of learners within the school and curriculum context are met. This includes learners who have additional support needs. Any child who needs more or different support to what is normally provided in schools or pre-schools is said to have ‘additional support needs’. Note that the term Early Learning and Childcare (ELC) is now used instead of pre-school. However this term is currently still within the ASL Act 2004 as amended).

The Scottish education system has been designed to be an inclusive and ‘needs led’ system which does not require a formal identification or label to be in place in order for a child or young person to receive support. However, it is extremely important that this is not inferred or interpreted by the learner, the family and professionals as the school or local authority as not ‘believing in’ or supporting dyslexia. The label of dyslexia and the understanding of what it means to that individual can be very important to the learner and their family. The importance of this should not be underestimated.

The quotations below have been taken from the book ‘Dyslexia is My Superpower (Most of the Time)’ and they reinforce the importance of learners understanding their dyslexia and of being told their dyslexia has been identified.

“It was a big relief when I found out and my grades started to improve.”

“I found out I was dyslexic and then I got to do what I am good at.”

“I felt a bit relieved when I found out I was dyslexic because I was hoping I wasn’t just thick. Before this I thought I was just not that smart”.

“When I was 5 a teacher told my mum I had problems and mum found out I had dyslexia. Its very important to get an early diagnosis and not to let it scare you”.

“When I was finding things hard and everyone else knew what they were doing, it didn’t feel good. I felt like they knew about things and I didn’t. Now it feels…not easier…but that it makes sense. The diagnosis answered a question for me”.

Watch the film ‘Dyslexia: Educate me’. It is a film about dyslexia and the experiences shared by many dyslexic people throughout the Scottish education system and beyond. The film was made by a predominantly dyslexic crew.

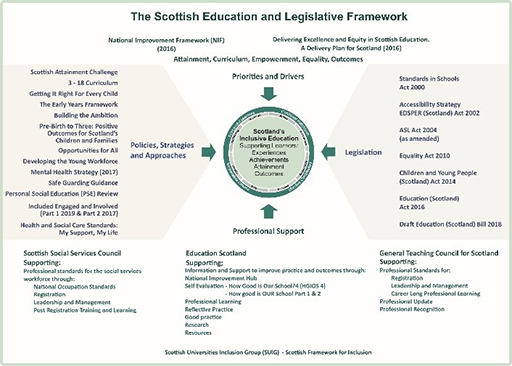

Module 2 highlighted that despite the wide range of legislation and policies highlighted in Figure 2, these support entitlements to inclusion, support and the identification of needs. Achieving inclusion and equality for all learners is a complex process, which requires:

- Understanding of legislative and professional duties at all levels

- Appropriate planning at all levels

- Appropriate collaboration

- A clear process to identify and support learners’ needs

Identification of dyslexia in Scottish schools

In module 2, activity 2 you considered some of the broader factors which contribute towards the process of achieving inclusion and equality for all learners. You may wish to revisit your notes.

Activity 2 Reflective Task

In your Reflective Log:

- Evaluate your understanding of the support and identification process of dyslexia

- Include the perspectives of all stakeholders – the learner, family members and practitioners

- Outline how comfortable you are just now participating in the identification process of dyslexia

Modules 1 and 2 highlighted the key role and entitlements that inclusive practice has within the Scottish context for education. It provided you with an opportunity to explore what is meant by additional support needs. (Refresh your memory of sections 1.1 and your Reflective Log for each module). This module will focus on identification within the Scottish context and aims to help you explore the following questions:

- Why do we need to identify dyslexia?

- How is the information to identify dyslexia gathered within the collaborative identification process?

- In your setting, what evidence do you have that there is an understanding that the process of monitoring and assessment, as part of Curriculum for Excellence, is used to identify and support additional support needs?

Section 4 provides further detailed information on the identification and assessment process for dyslexia and literacy difficulties.

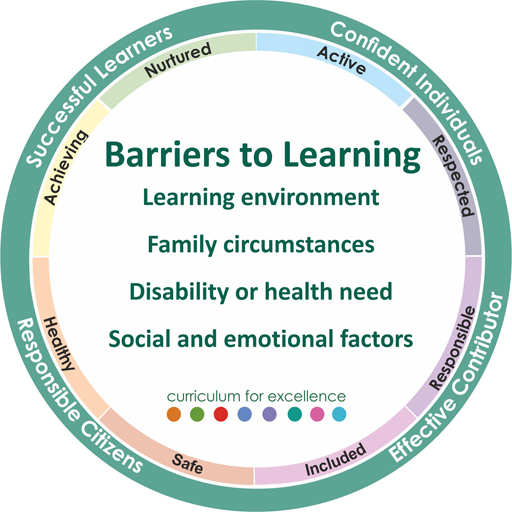

1 Why do we need to identify dyslexia?

The identification of dyslexia is not a matter of choice for schools and local authorities. There is a clear legislative framework in Scotland which underpins the system for identifying dyslexia. This makes provision for, and reviews the provision for the additional support needs of children and young people who face a barrier to learning. This includes the identification of dyslexia. Whilst additional support needs can arise for any reason, the legislation is focussed on addressing the impact of need on learning. Education authorities have a duty to identify and assess additional support needs arising from the barriers to learning and to make provision to meet individual support needs of all children and young people. The provision of support is not, however, dependent on a formal ‘label’ or diagnosis and should be child-centred.

The ‘learning’ takes place within the context of the school curriculum. As highlighted on Education Scotland’s website, the term curriculum is understood to mean:

‘Everything that is planned for children and young people throughout their education, not just what happens in the classroom’.

This totality of experiences is not specific to subject areas but also applies to and includes the ethos and life of the school as a community, curriculum areas and subjects, interdisciplinary learning and opportunities for achievement.

Activity 3

2

In your Reflective Log complete column 2 in the table ‘Factors giving rise to additional support needs’.

| Factors giving rise to additional support needs | Possible Barriers |

|---|---|

| Learning environment | |

| Family circumstances | |

| Disability or health need | |

| Social and emotional factors |

Answer

| Factors giving rise to additional support needs | Possible Barriers |

|---|---|

| Learning environment | At nursery, school, home and extra curricular settings. Learners may experience barriers to their learning, achievement and full participation in the life of the school. These barriers may be created as the result of factors such as

|

| Family circumstances | Circumstances within the learner’s home and family life can influence and impact on their health and wellbeing and their ability to actively participate in the full range of opportunities that school and the curriculum can provide. Factors may give rise to additional support needs; e.g.

Note - All looked after children are considered to have additional support needs, unless assessments find that support is not needed. |

| Disability or health need | This may mean that additional support is required; for example, where a learner has a

|

Social and emotional factors | This may include:

|

The above four factors may impact on the learner with dyslexia

3

The barriers to learning are not defined as being those of the child. As highlighted in question 1 the barriers arise from factors such as the learning environment, health and disability, social and emotional factors and family circumstance. There is a range of support strategies and approaches which can be implemented to help reduce the impact. These strategies do not always require resources to be purchased or to assume that 1-1 support is the most appropriate support.

In your Reflective Log consider the supports and approaches you use and recommend to colleagues. Then complete the third column in the table below: Possible Support Approaches/Strategies.

| Possible Impact | Possible Support Approaches/Strategies | |

Learning Environment (This can include Nursery, School , Home, school activities , out of school activities) Physical environment Learning and teaching materials |

| |

| Difficulty in demonstrating their cognitive ability – discrepancy between what they know verbally and what they can write down | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Family Circumstances |

| |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Disability or Health Need |

| |

| Social and Emotional Factors |

|

Answer

Please note these lists are not exhaustive.

| Possible Impact | Possible Support Approaches/Strategies | |

Learning Environment (This can include Nursery, School , Home, school activities , out of school activities) Physical environment Learning and teaching materials |

|

|

| Difficulty in demonstrating their cognitive ability – discrepancy between what they know verbally and what they can write down |

Free text and speech recognition software, Scottish voice – access CALL Scotland’s website and the technology section within the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Family Circumstances |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Disability or Health Need |

|

|

| Social and Emotional Factors |

|

|

1.2. Assessment/identification and legislation

In module 2 a summary overview of the legislative framework was available for you to download. This section will explore the relevant legislation, guidance and reviews in further details.

Additional Support for Learning

The Scottish Government wants all children and young people to be able to get the most from the learning opportunities which are available to them, so that they can realise their full potential, in learning, in work and in life.

Through the Getting it right for every child approach and Curriculum For Excellence, the Scottish Government has set out its ambition for services provided to children and young people, and for their learning. An important part of the approach is the recognition that all children and young people are different. To enable them to reach their full potential some will need additional support.

Supporting Children’s Learning: Statutory Guidance on the Education (Additional Support for Learning) Scotland Act 2004 (as amended) - Code of Practice (Third Edition) 2017

This is the third edition of the code and replaces all previous versions. This third edition takes account of the amendments in the 2016 Act which extended certain rights to children aged 12 and over 15. It explains the duties on education authorities and other agencies to support children’s and young people’s learning. It provides guidance on the Act’s provisions as well as on the supporting framework of secondary legislation.

Education authorities and appropriate agencies, such as NHS Boards, are under a duty to have regard to the code when carrying out their functions under the Act. The code is designed to help them make decisions effectively but cannot be prescriptive about what is required in individual circumstances. Education authorities and appropriate agencies must ensure that their policies, practices and information and advice services take full account of the legal requirements of the Act.

The code includes brief case studies and examples of good practice to illustrate some of the processes involved in applying the Act’s main provisions. These do not offer definitive interpretations of the legislation since these are ultimately a matter for the courts.

Education (Scotland) Act 2016

The Education Scotland Act 2016 which was passed by the Scottish Parliament in March 2016 makes amendments to the Additional Support for Learning Act. These amendments provide children aged 12-15, who are able to use them, with a range of rights under the Additional Support for Learning Act.

The 2016 Act is the second amendment to the Additional Support for Learning Act. To support understanding of the amended legislation, a Keeling Schedule has been produced. This shows the amendments which were made to the Act by the 2016 Act (in blue and purple). Changes made by the 2009 Act are already incorporated.

As part of the preparation for the implementation of the Act, information for parents was developed. This explains all of the provisions of the Act. Page 6 sets out information on Additional Support for Learning changes.

These changes came into force in January 2018.

The purpose of the report to Parliament is to document the progress in implementing the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004 (as amended). The report fulfils the duties placed on Scottish Ministers at sections 26A and section 27A of the amended Act. These duties are:

- that Scottish Ministers must report to the Scottish Parliament in each of the 5 years after the commencement of the Act on what progress has been made in each of those years to ensure that sufficient information relating to children and young people with additional support needs is available to effectively monitor the implementation of this Act. (section 26A)

- that Scottish Ministers must each year collect from each education authority information on:

- the number of children and young persons for whose school education the authority are responsible having additional support needs

- the principle factors giving rise to the additional support needs of those children and young persons

- the types of support provided to those children and young persons, and

- the cost of providing that support.

Scottish Ministers must publish the information collected each year. (Section 27A)

In addition to the information required by the Act, Scottish Ministers will provide further information and evidence from a number of sources. This will enable the data required by the duties to be set in context and offer a fuller picture of implementation of the legislation. Sources include: Enquire, ASL Resolve and Common Ground Mediation, Independent Adjudication, Additional Support Needs Tribunals for Scotland, the Scottish Government, Take Note, Education Scotland and the Advisory Group for Additional Support for Learning (AGASL).

This information presents as full a picture as possible of the implementation of Additional Support for Learning. This includes information from the national statistics collection of data on pupils.

Additional support for learning review - the 2020 independent review ‘Support for Learning: All our Children and All their Potential’

In module 2 you looked at an overview of this review which was conducted in 2019. It concluded with the submission of the report and recommendations to Scottish Ministers and COSLA. The review was led by Angela Morgan.

The remit of the review was to consider the implementation of the legislation: across early learning and childcare centres, primary, secondary and special schools; the quality of learning and support; the different approaches to planning and assessment; the roles and responsibilities of support staff; and the areas of practice that could be further enhanced through better use of current resources to support practice, staffing or other aspects of provision.

The report outlines the approach taken, the evidence heard and draws out a number of interconnected themes in making recommendations for improvement. The report makes clear that there is ‘no fundamental deficit in the principle and policy intention of the Additional Support for Learning legislation and the substantial guidance accompanying it’. However, there are difficulties ensuring the implementation of this into practice.

The review’s evidence affirmed,

‘that despite the many dedicated, skilled and inspiring professionals who care deeply about children and young people with additional support needs, Additional Support for Learning is not visible or equally valued within Scotland’s Education system. Consequently, the implementation of Additional Support for Learning legislation is over-dependent on committed individuals, is fragmented and inconsistent and is not ensuring that all children and young people who need additional support are being supported to flourish and fulfil their potential.’

An action plan has been developed to support the reviews recommendations. The themes are below.

- Vision and visibility

- Mainstreaming and inclusion

- Maintaining focus, but overcoming fragmentation

- Resources

- Workforce development and support

- Relationships between schools and parents

- Relationships and behaviour

- Understanding rights

- Assurance mechanism

Select here to download the Summary report of the Support for Learning: All our Children and All their Potential.

Select here to download the Review’s Action Plan.

Select here to download the full review: Support for Learning: All our Children and All their Potential

1.3. Models for inclusion

“If it doesn’t feel like it should then it isn’t inclusion”

Presumption to provide education in a mainstream setting: guidance - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

‘Inclusive education in Scotland starts from the belief that education is a human right and the foundation for a more just society. An inclusive approach, with an appreciation of diversity and an ambition for all to achieve to their full potential, is essential to getting it right for every child and raising attainment for all. Inclusion is the cornerstone to help us achieve equity and excellence in education for all of our children and young people.’

The flexibility of the Scottish curriculum and guidelines which include both the 5-14 Curriculum and Curriculum for Excellence have provided opportunities for inclusive approaches within mainstream schools to be better understood by all stakeholders and implemented into practice. The development of inclusive practice has been and continues to be a journey and one which is linked to understanding the overlap between disability and additional support needs which have been highlighted in module 2.

There are a number of ‘models’ of disability which have been defined over recent years. The two which are most frequently discussed and highlighted are the ‘social’ and the ‘medical’ models of disability; other models have evolved and developed from these 2 models. This module will focus on the 2 most commonly referred to models.

Module 2, Section 1.5, introduced the models of disability. Here they are explained further.

Medical model of disability

The medical model of disability says that people are disabled by their impairments or differences. The social model of disability says that disability is caused by the way society is organised.

Under the medical model, impairments or differences should be ‘fixed’ or changed by medical and other treatments, even when the impairment or difference does not cause pain or illness.

The medical model looks at what is ‘wrong’ with the person and not what the person needs. It creates low expectations and leads to people losing independence, choice and control in their own lives.

Social model of disability

The social model of disability says that disability is caused by the way society is organised, rather than by a person’s impairment or difference. It looks at ways of removing barriers that restrict life choices for disabled people. When barriers are removed, disabled people can be independent and equal in society, with choice and control over their own lives.

Disabled people developed the social model of disability because the traditional medical model did not explain their personal experience of disability or help to develop more inclusive ways of living.

The social model of disability is more in line with the vision for inclusion in Scotland for all our learners - both disabled and non-disabled. The social model is more inclusive in approach for the following reasons

- Anticipatory thought is given to how disabled people can participate in activities on an equal footing with non-disabled people. Certain adjustments are made, even where this involves time or money, to ensure that disabled people are not excluded.

- The Scottish educational context also supports this model. All 3 modules highlight the range of educational and equality legislation along with the policies which have inclusion within their foundation and support a ‘needs led’ inclusive education system for all learners.

1.4. Rights and participation

By May 2021, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) will be fully incorporated into Scots law with a legal duty on all public bodies to protect and respect the rights of all children. The aspiration is for all children and young people aged 3-25 to have the opportunity to contribute to decisions and know that their ideas are listened to, valued and considered. Children’s rights and participation are an identified priority in several national policies, guidance and strategies including:

- Children`s and Young People (Scotland) Act (2014) Parts 1, 3 and 9

- Progressing the Human Rights of Children in Scotland: An Action Plan (2018 – 2021)

- Child`s Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessments (CRWIA) Guidance (2019)

- Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC)

- Common Core of Skills, Knowledge and Understanding and Values for the `Children`s Workforce` in Scotland (2012)

- Fairer Scotland Action Plan (2016)

- National Guidance: Child Protection Committees and Child Protection Chief Officers (2018)

- Education Scotland’s suite of self-evaluation documents to support schools, early learning and childcare (ELC) settings Community Learning and Development, and colleges include several references to children’s and young people’s rights and participation. For example, the fourth edition of How Good Is Our School (HGIOS4) states that we have a duty to ‘involve children and young people in decisions about how their needs should be met’.

- How Good Is Our School? Fourth edition (HGIOS?4)

- How Good is our Early Learning and Childcare?

- How Good is the Learning and Development in our Community?

- How Good is our College?

Views of Learners - The Young Inclusion Ambassadors

The Young Inclusion Ambassadors have developed resources to support schools and local authorities to hear the views of learners who have additional support needs and disabilities about their experiences of inclusion in Scottish schools – what works and what can help improve their experiences.

The resources aim to:

- Raise awareness of inclusion

- Provide free resources for professional development

The young people made a film called ‘Ask us, Hear us, Include us’ to share their experiences and below are some quotes from them.

“Just not being someone on the outside looking in and be able to have the same opportunity and education”

“So it’s nice for people not just to presume that you can’t do something”

Activity 4 Young Inclusion Ambassadors

Access the online resources developed by the Young Inclusion Ambassadors

- Watch the film and look at the accompanying resources

- Make notes in your Reflective Log. You may wish to use your Action Plan to incorporate opportunities to share these resources with your colleagues.

- How and when will they be used?

- How will the impact of the resources and professional engagement opportunities be evaluated?

- Can you build on the resources in your school community?

Suggested further reading

Research paper by Professors Mel Ainscow and Susie Miles: Developing inclusive education systems: how can we move policies forward? http://www.ibe.unesco.org/ fileadmin/ user_upload/ COPs/ News_documents/ 2009/ 0907Beirut/ DevelopingInclusive_Education_Systems.pdf

Key Principles for Promoting Quality in Inclusive Education Recommendations for Practice

https://www.european-agency.org/ sites/ default/ files/ Key-Principles-2011-EN.pdf

2. Understanding dyslexia

Introduction

In this section we look at:

2.1. Identification research

2.2. The positive aspects of dyslexia

2.3. Language development and identification of dyslexia

2.4. Numeracy development and the identification of dyslexia

2.5. Wellbeing development and the identification of dyslexia

2.6. Suggested reading and films

2.1. Identification research

A range of different dyslexia definitions and approaches to identifying dyslexia are used across the world. The variations can be due to the range of different policies from education departments and national approaches such as a result of inputs from various stakeholders.

Understanding the range of factors which influence the various dyslexia definitions is helpful as it can explain why there may be a particular focus on one area. For example, if the definition is to support a specific area of research it may focus on this. Some definitions are very defined, e.g. The British Psychological Society focuses strongly on ‘word level’ difficulties and this is very evident in their definition below:

‘Dyslexia is evident when accurate and fluent word reading and/or spelling develops very incompletely or with great difficulty. This focuses on literacy at the word level and implies that the problem is severe and persistent despite appropriate learning opportunities.' (1999) Dyslexia, Literacy and Psychological Assessment, Report of the Working Party of the DECP of British Psychological Society (BPS)

As you are aware, in January 2009, the Scottish Government working group, which included Dyslexia Scotland and the Cross-Party Group on Dyslexia in the Scottish Parliament published the Scottish working definition of dyslexia. The aim of this particular definition is to provide a description of the range of indicators and characteristics of dyslexia as helpful guidance for educational practitioners, learners, parents/carers and others. This definition has been endorsed by the Association of Scottish Principle Educational Psychologists (ASPEP).

The literature review in Section 3, ‘Enquiry and Research’ of the Routemap, has a number of papers which will support your professional development and enquiry in this area.

Below are 2 articles which discuss this issue.

There are a number of issues here that highlight what appears to be serious conceptual confusion in the field. These carve out an important agenda both for research and practice.

In order to consider what is at stake, it is helpful first to refer to the important theoretical framework proposed by Morton and Frith (1995; see also Morton, 2004). According to this framework, it is important when considering developmental disorders to separate the biological, the cognitive and the behavioural levels of explanation. Importantly, it is necessary to acknowledge that developmental disorders are dynamic and there are environmental interactions at all levels. So the behavioural manifestations of disorders, such as dyslexia, change with time, and also in different contexts – for example we would see different behaviours in a child taught to read in Italian or in one who received early intervention.

The phonological deficit theory of dyslexia, featured in the documentary, is a theory at the cognitive level. It explains a constellation of behaviours that are normally associated with dyslexia (short-term memory problems, word-finding difficulties, etc.). The phonological deficit theory is a well-specified, falsifiable theory that so far has not been refuted. What many respondents are upset about is that certain behaviours often associated with dyslexia are not explained by the theory – e.g. visual problems, problems of organisation and of motor control. Of course, it is correct that these behaviours often co-occur with dyslexia; they signal important co-morbidities. Why they do is poorly understood. Next steps must involve seeking both biological and cognitive explanations of these associated disorders so that ultimately we can begin to unpick what is dyslexia (the construct under threat), what is not dyslexia and why these behaviours co-occur so frequently. But, to gather everything under the umbrella of ‘dyslexia’ helps neither theory nor practice. As for the call for ‘cut-off points’ for ‘dyslexia’, we can as a profession agree criteria for extra time or a laptop computer, but it is meaningless to imagine quantitative criteria defining a dynamic developmental disorder.

University of York

https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/ volume-18/ edition-12/ dyslexia-debate-continues

Download the article Dyslexia by any other name

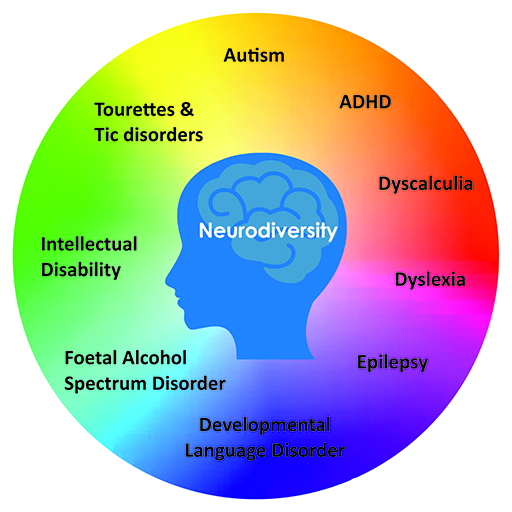

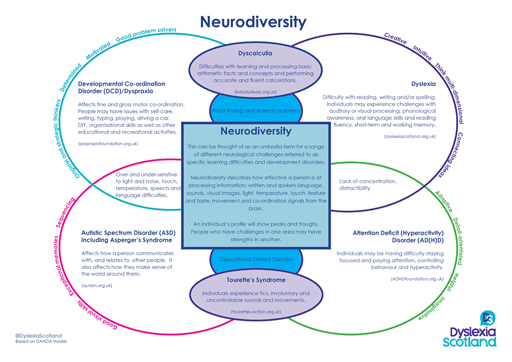

Dyslexia and neurodiversity

Modules 1 and 2 explored the increasing use of the term neurodiversity to represent a range of neurodevelopmental differences.

Dyslexia Scotland’s Dyslexia Voice magazine published an article in March 2016 which promoted the view that neurodiversity should be seen as valuable resource – one which has been overlooked in relation to education - and that brain patterns previously referred to as ‘disorders’ are actually different patterns of healthy wiring. They are just wired up to support different strengths in function.

In England the Department of Education and Skills funded a project called ‘The Train the Trainer: Teaching for Neurodiversity’ which ran until 31st March 2017. See further information on the British Dyslexia Association website

You can access the link for the guide which the project published here: ‘Teaching for Neurodiversity A Guide to Specific Learning Difficulties’

The project highlighted that the concept of neurodiversity is spreading across a range of areas within education. Those who are using the term define it as a means of empowerment, to promote the positive qualities possessed by those with a neurological difference. It encourages people to view neurological differences such as autism, dyslexia and dyspraxia as natural and normal variations of the human genome. Further, it encourages them to reject the culturally entrenched negativity, which has typically surrounded those that live, learn and view the world differently.

Activity 5

In your Reflective Log provide a comment on the following questions:

- What definition does your local authority use to support the identification of dyslexia?

- What are the implications/impact of the chosen definition?

- What is your professional view regarding dyslexia and neurodiversity?

- Hot topics/questions

The route map includes some questions to discuss with colleagues for which there is not necessarily a clear answer. Some of the questions below are for you engage with during professional discussion or to include within your own reflections and action research:

Download a discussion sheet to help you collate responses

- Should the focus and resources be used on the identification or label of dyslexia or should schools concentrate on meeting the needs of the child and young person through a collaborative process?

- Should teachers in Scotland be required to participate in training to carry out the identification of dyslexia?

- Should teachers in Scotland be required to gain qualifications to carry out the identification of dyslexia?

- How can we provide a continuity of support and access to support for dyslexia and inclusion across Scotland?

- How should independent assessments of dyslexia be regarded and supported within schools and what is the legal status of independent assessments?

- Are the roles of identification and tracking for dyslexia understood within ‘Assessment is for Learning’? Is it understood that when meeting learners’ needs the assessment of learning informs the next steps and should be continuous and separate from ‘identification’ of dyslexia. The label alone will not provide appropriate support; this is achieved by regular tracking and reviewing of learners needs.

- Can the identification process for dyslexia be a positive experience for children and young people? Does the process enable them to understand their strengths and difficulties in a supportive way and provide opportunities for their views to be sought?

- Are children and young people, teachers and parents/carers provided with appropriate information/feedback to support their understanding of which approaches/strategies are effective and why?

2.2. Positive aspects of dyslexia

Strengths of dyslexia providing a positive impact on the four factors of barriers to learning

It is important to understand, recognise and share with the learner and their family that there are positive aspects to dyslexia. We should emphasise that using the learner’s strengths which are identified during the identification process will help develop a range of supportive skills. If this area is not explored the negative aspects of dyslexia can become the dominant factors and impact negatively on the learner’s health, wellbeing and achievements.

If a learner has the right support and an inclusive, accessible learning environment, some of the difficulties experienced will be minimised and in some cases will not impact on the learner’s abilities and opportunities to engage fully with their education.

Activity 6

Insert the words into the correct columns. Please note the words can be may be used more than once.

Resilience, Creativity, Determination, Family support, Problem solving, Empathy with different approaches, Benefits from different ways of thinking and problem solving, Holistic thinking, Enquiring questioning, Self-belief, Adaptable, Focused, Positive mind set, Acceptance of people’s individuality, Time management, Diversity, Self-efficacy, Sense of control, Transferable skills, Understanding difference, Organisation, Number Skills, Spatial awareness, Visualisation oral language skills, Physical skills – dance/sport, Thorough preparation, Imaginative use of IT, Strong subject knowledge

| Learning Environment | Family Circumstances | Disability or health need | Social and emotional factors |

|---|---|---|---|

Answer

Please note that this is not exhaustive and you may have other suggestions.

| Learning Environment | Family Circumstances | Disability or health need | Social and emotional factors |

|---|---|---|---|

Creativity Problem solving Empathy with different approaches Benefits from different ways of thinking and problem solving Holistic thinking Time management Transferable skills Thorough preparation Imaginative use of IT Strong subject knowledge Spatial awareness Visualisation Oral language skills Physical skills – dance/ sport | Resilience Creativity Determination Family support Empathy with different approaches Benefits from different ways of thinking and problem solving Holistic thinking Enquiring questioning Self-belief Adaptable Positive mind set Acceptance of people’s individuality Time management Transferable skills Understanding difference | Adaptable Focused Positive mind set Acceptance of people’s individuality Diversity Self-efficacy Sense of control Transferable skills Understanding difference Thorough preparation Imaginative use of IT | Resilience Creativity Determination Family support Problem solving Holistic thinking Enquiring questioning self-belief Adaptable Focused Positive mind set Time management Self-efficacy Sense of control Understanding difference Thorough preparation Imaginative use of IT |

2.3. Language development and identification of dyslexia

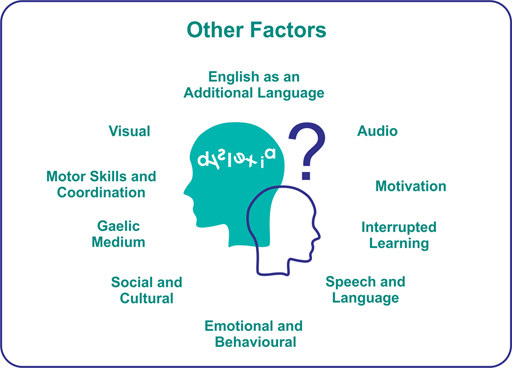

Module 2 and the Routemap highlighted the importance of language development. There may be a number of reasons why a learner’s language is not at the expected level for their age.

Activity 7

In your Reflective Log consider some possibilities why this may be the case.

Click ‘reveal’ to see some examples of what we thought.

Discussion

- Speech and Language difficulties

- Speech and Language delay

- EAL

- ASD

- Attention deficit disorder

- Poor/low level spoken vocabulary in the home

- Lack of reciprocal interaction at young developmental age

- Neglect

- Lack of attunement

- Negative inter-generational patterns

- Hearing difficulties

- Parents with poor literacy skills

- Lack of literacy rich experiences in early years

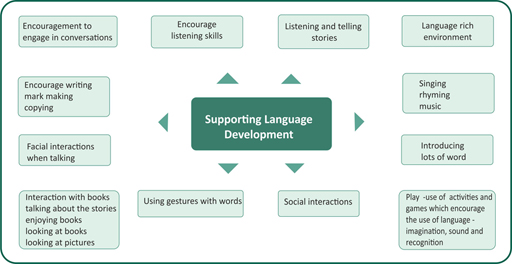

To identify strengths and areas of difficulty of a learner’s language skills it is vital to understand what the term ‘language development’ means. Modules 1 and 2 highlighted areas of literacy development and this contributes to the wider language development as figure 5 highlights.

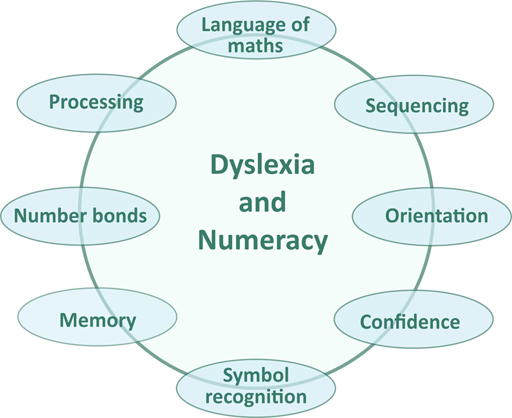

2.4. Numeracy development and the identification of dyslexia

The Numeracy Across Learning Principles and Practice Paper states the following:

All schools, working with their partners, need to have strategies to ensure that all children and young people develop high levels of numeracy skills through their learning across the curriculum. These strategies will be built upon a shared understanding amongst staff of how children and young people progress in numeracy and of good learning and teaching in numeracy. Collaborative working with colleagues within their own early years setting, school, youth work setting or college and across sectors will support staff in identifying opportunities to develop and reinforce numeracy skills within their own teaching activities.

Being numerate helps us to function responsibly in everyday life and contribute effectively to society. It increases our opportunities within the world of work and establishes foundations which can be built upon through lifelong learning. Numeracy is not only a subset of mathematics; it is also a life skill which permeates and supports all areas of learning, allowing young people access to the wider curriculum. We are numerate if we have developed the confidence and competence in using numbers which will allow individuals to solve problems, analyse information and make informed decisions based on calculations. A numerate person will have acquired and developed fundamental skills and be able to carry out number processes but, beyond this, being numerate also allows us to access and interpret information, identify possibilities, weigh up different options and decide on which option is most appropriate. Numeracy is a skill for life, learning and work. Having well-developed numeracy skills allows young people to be more confident in social settings and enhances enjoyment in a large number of leisure activities. For these and many other reasons, all teachers have important parts to play in enhancing the numeracy skills of all children and young people. Numerate people rely on the accumulation of knowledge, concepts and skills they have developed, and continually revisit and add to these. All practitioners, as they make use of the statements of experiences and outcomes to plan learning, will ensure that the numeracy skills developed from early levels and beyond are revisited and refreshed throughout schooling and into lifelong learning.

Download the Numeracy across Learning Principles and Practice Paper.

Dyslexia and difficulties with numeracy and maths

Module 2 explained that the associated characteristics within the Scottish working definition can have an impact on some learners and their ability to develop their numeracy and math skills.

Download Dyslexia Scotland’s information leaflet on Ideas for Supporting Maths

Learners with numeracy difficulties may:

- Struggle with the basic concept of numbers, e.g., recognising a group of four counters as "four" or equate the numeral ‘4’ with four concrete objects

- Have difficulty with fundamental mathematical concepts, e.g., addition, subtraction, multiplication and division

- Have limited skills in estimation tasks or be able to sense whether their answer is correct or approximately correct

- Have no devised strategies to compensate for lack of recall

- Find it hard to lay out their work neatly, resulting in mistakes, e.g., in adding up a column of numbers

- Struggle with mental arithmetic, possibly as a result of short-term and working memory issues

- Display high levels of maths anxiety and deploy avoidance tactics

Dyscalculia definition

In Scotland there is no formal definition for dyscalculia and the recommendation would be to follow the same principles and practice as the dyslexia identification pathway using a collaborative process.

Download Dyslexia Scotland’s leaflet on Dyscalculia

Consider the definitions below:

British Dyslexia Association

Dyscalculia is usually perceived of as a specific learning difficulty for mathematics, or, more appropriately, arithmetic. Currently (January 2015) a search for ‘dyscalculia’ on the Department for Education’s website gives 0 results as compared to 44 for dyslexia, so the definition below comes from the American Psychiatric Association (2013):

“Developmental Dyscalculia (DD) is a specific learning disorder that is characterised by impairments in learning basic arithmetic facts, processing numerical magnitude and performing accurate and fluent calculations. These difficulties must be quantifiably below what is expected for an individual’s chronological age, and must not be caused by poor educational or daily activities or by intellectual impairments”.

The BDA are of the view that because definitions and diagnoses of dyscalculia are in their infancy and sometimes contradictory, it is difficult to suggest a prevalence, but research suggests it is around 5%. However, ‘mathematical learning difficulties’ are certainly not in their infancy and are very prevalent and often devastating in their impact on schooling, further and higher education and jobs. Prevalence in the UK is at least 25%.

Developmental Dyscalculia often occurs in association with other developmental disorders such as dyslexia or ADHD/ADD. Co-occurrence of learning disorders appears to be the rule rather than the exception. Co-occurrence is generally assumed to be a consequence of risk factors that are shared between disorders, for example, working memory. However, it should not be assumed that all dyslexics have problems with mathematics, although the percentage may be very high, or that all dyscalculics have problems with reading and writing. This latter rate of co-occurrence may well be a much lower percentage.

Because mathematics is very developmental, any insecurity or uncertainty in early topics will impact on later topics, hence to need to take intervention back to basics.

Recent research has identified the heterogeneous nature of mathematical learning difficulties and dyscalculia, hence it is difficult to identify via a single diagnostic test. Diagnosis and assessment should use a range of measures, and test protocol, to identify which factors are creating problems for the learner. Although on-line tests can be of help, understanding the difficulties will be better achieved by an individual person-to-person diagnostic, clinical interview.

This view supports the current methodology and collaborative identification process in Scotland.

Department for Education and Skills (DfES) England

Dyscalculia is a condition that affects the ability to acquire arithmetical skills. Dyscalculic learners may have difficulty understanding simple number concepts, lack an intuitive grasp of numbers, and have problems learning number facts and procedures. Even if they produce a correct answer or use a correct method, they may do so mechanically and without confidence.

Very little is known about the prevalence of dyscalculia, its causes, or treatment. Purely dyscalculic learners who have difficulties only with number will have cognitive and language abilities in the normal range, and may excel in nonmathematical subjects. It is more likely that difficulties with numeracy accompany the language difficulties of dyslexia.

Activity 8

- Look at your school/local authorities’ policies for numeracy and math

- Does the policy make a clear connection with dyscalculia or numeracy difficulties?

- In your view can this be improved to support learners and staff and if so how?

Use your Reflective Log to note your thoughts and findings.

Action Plan

- Use your Action Plan to identify next steps you will take, who you will discuss this with and how the impact can be evaluated

2.5. Wellbeing development and the identification of dyslexia

Modules 1 and 2 highlighted the negative link between dyslexia, low self-esteem and anxiety.

It is common for everyone at some point to experience low feelings, anxiety and stress. However, when this is ongoing and has an impact on someone’s ability to do things then it can become a bigger problem. Some people whose dyslexia has not been recognised may have feelings that cause them emotional and physical distress. The impact on being able to work with and assess children and young people during the Covid pandemic will contribute towards a rise of anxiety and stress for all involved. A wide range of information, support and guidance has been produced to support learners and staff wellbeing during this time.

Activity 9

Match the correct reactions that people may experience

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 6 items in each list.

Confusion

Anger

Negativity

Anxiety

Hopelessness

Depression

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.‘Why should I bother?’ thoughts, possibly leading to giving up.

b.Anger turns itself inwards. People may feel alone because they are not understood. Some people may isolate themselves because of their low self-esteem and feelings of not being ‘good enough’. Switching off and giving up leads to further negative thinking.

c.They feel their efforts make no difference and it is only luck if they succeed. Self-esteem is low and they always predict the worst. They feel that others judge them negatively and compare themselves less favourably with peers and siblings.

d.Their experience of failure leads them to think they will fail again.

e.From frustration that they, and others, do not understand dyslexia.

f.They don’t fully understand dyslexia and why they experience difficulties and have a mixture of abilities. They believe that they are ‘stupid’.

- 1 = f,

- 2 = e,

- 3 = c,

- 4 = d,

- 5 = a,

- 6 = b

2.6. Suggested reading and films

Further information is available in Dyslexia Scotland leaflets: https://www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk/ our-leaflets. Many of these leaflets also have suggestions for further reading.

For example:

- Dyslexia and self esteem

- Identification of dyslexia in schools - information for parents

- Explaining dyslexia to children

- Youth information - what is dyslexia?

Access a range of short films on Dyslexia Scotland’s YouTube channel - https://www.youtube.com/ channel/ UC1aSDfa8h-3IooqEvownR7A

Download the Dyslexia Scotland reading lists or click on the link below:

https://dyslexiascotland.org.uk/ sites/ default/ files/ library/ Reading%20lists%20Dec%2016.pdf

What equality law means for you as an education provider – Schools https://education.gov.scot/ improvement/ Pages/ inc16schools.aspx

‘Dyslexia is My Superpower (Most of the Time)’ Margaret Rooke ISBN 978-1-78592-299-2

Download ‘A Framework for Assessment’

A summary of resources to support learning, teaching and assessment within numeracy and mathematics is available on the National Improvement Hub Summary Page

Within this page you will gain access to links to all current support material which includes curriculum documentation, key publications, the professional learning resources and research links.

Free sample video tutorials to help with dyscalculia and mathematical learning difficulties: https://www.mathsexplained.co.uk/ ?ref=bda (Please note additional charges to access the full range)

Now that you have finished section 1 you can try Quiz 1. This activity counts towards your final pass mark which needs to be at least 80%

3. Supporting learners and families

Introduction

In this section we look at:

3.1. Support through Curriculum for Excellence

3.2. Support through inclusive practice

3.3. Supporting dyslexia and learning

3.4. Information for learners and families

3.5. Suggested reading

3.1. Support through Curriculum for Excellence

Section 1 highlights that Curriculum for Excellence was designed to be flexible in order to meet the needs of all learners, recognising that one size does not fit all. This flexibility is an important requirement when planning to support learners who are dyslexic, each with their own individual profile of strengths and areas where support is needed. Barriers to learning and participation are sometimes made unintentionally. This is why it is important that:

- Positive relationship are supported and developed between learners, staff and parents/carers.

- There is effective communication between families and educational staff

- There is clear, effective communication within local authorities – between the ‘central officers’ and educational establishments.

Schools and local authorities understand their responsibilities and duty with regards to planning for learners who have additional support needs. If required to do so, consideration must be given to the design of the curriculum and how it is accessed. An example of this could be when a school amends their curriculum to reflect the interests and abilities of their pupils, offering tailored programmes such as dance, photography, laboratory skills and Open University modules. Such approaches contribute substantially towards closing the gap in achievement and attainment for learners.

Activity 10

In your Reflective Log complete the questions in the table.

- How flexible is your school curriculum?

- How accessible is your school curriculum?

- Are the needs of learners at the centre of planning? For example, flexible pathways, the number and choice of subjects they are able choose in secondary school.

3.2. Support through inclusive practice

Module 1 and 2 recap – Summary of dyslexia friendly schools and inclusive schools.

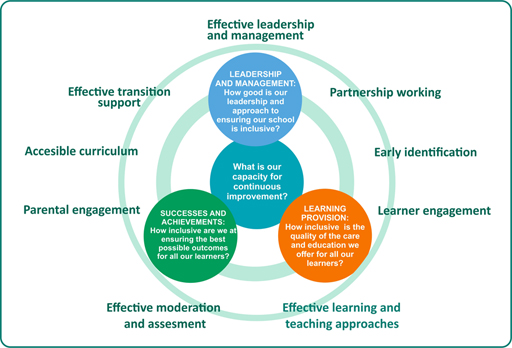

Dyslexia friendly practice is an important element of inclusive practice including approaches to learning and teaching which are child centred and support inclusive practice for all learners. A number of contributory factors support the development, recognition and implementation of inclusive practice within Scottish education with the aim of improving the educational experiences and outcomes of learners who are dyslexic.

This module has been developed to support you as you consider and contribute to improvements in your school communities which enable all stakeholders to become inclusive in their attitudes and practice. This will in turn improve the support and experience of learners with dyslexia and their families

Activity 11 Reflective Log task

Look back at your Reflective Logs from modules 1 and 2 and consider and evaluate your comments as you progress to this section. In your Reflective Log, critically examine, analyse and evaluate what impact learning about inclusive school communities has had on your thinking, learning and practice, and on learners and their learning. Include quotes and extracts of analysed evidence to support this.

3.3. Supporting dyslexia and learning

A positive and inclusive school ethos and understanding from staff contributes significantly to providing appropriate support for learners with dyslexia and their families – indeed this will be the same for all learners. Due to the individuality of all learners, it would not be appropriate to recommend specific resources from the many which are available. We do not make any set recommendations but leave teachers and others to evaluate resources for themselves and establish the most appropriate materials for the individual needs of learners as there is no ‘one size fits all’.

The Resources section within the Toolkit has a range of free resources:

http://addressingdyslexia.org/ resources

- Auditory and processing skills

- Comprehension

- Coordination

- Literacy

- Literacy – Pre-Phonics

- Literacy – Phonological awareness and phonics

- Literacy – Reading/writing/spelling

- Memory

- Numeracy and maths

- Visual processing

Dyslexia Scotland has a range of resources available on their website. Some are free to download, and some can be loaned to members.

Curriculum areas

Dyslexia can impact on all eight curriculum areas within Curriculum for Excellence in different ways depending on the individual.

It is important for class teachers to be aware of strategies which may help the curriculum area or interdisciplinary areas they are teaching.

Module 1 and 2 highlighted 2 sets of books below which will support staff across the curriculum:

- Supporting Pupils with Dyslexia at Primary School (2011): A series of 8 booklets that were provided to every primary school in Scotland which contains information and advice about dyslexia from the early stages to transition to secondary school. They also and also contain information on support for learning departments, school management teams and good practice when working with parents. These booklets can be downloaded by Dyslexia Scotland members from the Dyslexia Scotland website.

- Supporting Pupils with Dyslexia in the Secondary Curriculum (2013): A series of 20 booklets that were provided to every secondary school in Scotland whichaim to provide subject teachers and support staff with advice and strategies to support learners with dyslexia. The booklets can be downloaded from the Dyslexia Scotland website.

Curriculum accessibility

Differentiation

Activity 24, Section 2.2 in Module 2 highlights a range of different approaches to consider when planning effective and meaningful differentiation. Figure 9 provides a reminder. You may wish to revisit this section of module 2.

Activity 12 Curriculum Accessibility - Differentiation

Reflective questions for professional dialogue with colleagues.

The following questions can be used when engaging in professional dialogue during professional learning opportunities and discussions with colleagues. The outcomes from these discussions can support planning for professional learning opportunities and improvement plans.

You can collate the responses in your Reflective Log.

Download a discussion sheet if required.

Download Differentiation descriptions of the areas to share with your colleagues if required.

- What areas are being used in your school community to support differentiation?

| Area of differentiation | Commonly used in my school | Additional approaches | Ideas raised which have not been used |

| Task | |||

| Grouping | |||

| Resources /Support | |||

| Pace | |||

| Outcome | |||

| Dialogue and support | |||

| Assessment |

- Are there any areas of differentiation which your school is not using which you could support?

- Has any additional good practice been highlighted through our discussions?

3.4. Information for learners and families

Modules 2 and 3 highlighted the importance of effective communication when supporting learners and families through the dyslexia identification. Understanding and sensitivity is required to help all involved understand what is happening during this time and also to share the positive aspects of dyslexia.

There is a wide range of information designed to help practitioners support learners and families on the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit.

Select here to watch a short animation available on the Assessment and Monitoring section that provides an overview of the identification pathway (scroll down on the webpage).

Dyslexia Scotland's YouTube Channel also has a range of films which are helpful in supporting families, learners and professionals to understand dyslexia and help children with dyslexia at home. One which may be of particular help is on the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit : 'Dyslexia is Awesome and Rubbish' Select here to watch it (scroll down on the webpage).

There is also a range of short films that may help learners and their families on the Dyslexia Unwrapped website – an online hub for children and young people. Dyslexia Unwrapped by Dyslexia Scotland

3.5. Suggested Reading

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/auditory-processing-disorder/

The Dyslexia Assessment Dr Gavin Reid and Dr Jennie Guise

4. Assessment and planning

Introduction

In this section we look at:

4.1. Assessment within Curriculum for Excellence

4.2. Benchmarks and assessment of dyslexia

4.3. Supporting collaborative understanding of ASN assessment within Curriculum for Excellence

4.4. Identification pathway and Curriculum for Excellence

4.5. The process of identification

4.6. Planning

4.7. Reporting

4.8. Learner profile

4.9. Standardised assessments

4.10. Assessment arrangements

4.11. Transitions

4.12. Post 16 support

4.1. Assessment within Curriculum for Excellence

Recap Module 2

Section 1.1

Support for all learners begins within the classroom and is provided by the classroom teacher who holds the main responsibility for nurturing, educating and meeting the needs of all pupils in their class, working in partnership with support staff to plan, deliver and review curriculum programmes. Support for children and young people with dyslexia and also those who experience literacy difficulties and other additional support needs is achieved through universal support within the staged levels of intervention.

Gathering assessment information together to use in a dyslexia pathway is not the sole responsibility of a Support for Learning /ASN teacher. It is a collaborative process.

Is there a connection between Curriculum for Excellence assessment and assessment for dyslexia?

The Code of Practice (Third Edition) 2017 states that:

‘Assessment is seen as an ongoing process of gathering, structuring and making sense of information about a child or young person, and his/her circumstances. The purpose of assessment under the Act ultimately is to help identify the actions required to maximise development and learning. Assessment plays a key role in the authority’s arrangements for identifying children and young people who have additional support needs and who, of those, require a coordinated support plan. Assessment is a process supported by professionals and parents in most circumstances. It identifies and builds on strengths, whilst taking account of needs and risks. The assessment process also assumes the negotiated sharing of information by relevant persons and agencies.’

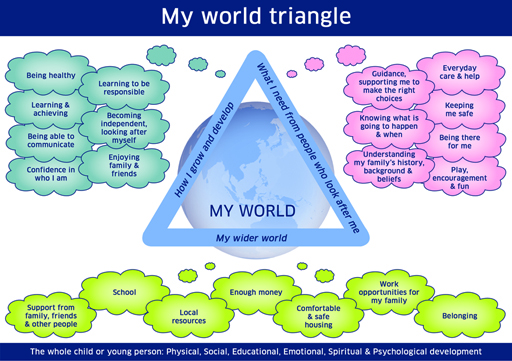

Assessment is a dynamic process, with the child or young person at the centre. As a result, it should not be separated from other aspects of the child’s life at school, home or in the community as illustrated in the My World Triangle above. It will usually include discussion with parents and professionals involved with the child or young person. This could be a class teacher, support for learning staff, speech and language therapist, social worker, foster carer or residential worker. It should build on other assessment information already available. It may involve observation in one or more day-to-day situations and/or individual work with the child or young person as required. The education authority should always try endeavour to seek and to take account of the views of the child or young person, unless there are particular circumstances to prevent this happening, or which make it inappropriate.

Curriculum for Excellence sets out the values, purposes and principles of the curriculum for children and young people aged 3 to 18.

The assessment system in Scottish schools is driven by the curriculum and so necessarily reflects these values and principles. The 2011 document ‘A Framework for Assessment’ was designed to support the purposes of Curriculum for Excellence and highlights that the purposes of assessment are to:

- Support learning that develops the knowledge and understanding, skills, attributes and capabilities which contribute to the four capacities

- Give assurance to parents, children themselves, and others, that children and young people are progressing in their learning and developing in line with expectations

- Provide a summary of what learners have achieved, including through qualifications and awards

- Contribute to planning the next stages of learning and help learners progress to further education, higher education and employment

- Inform future improvements in learning and teaching

Assessment is therefore an integral part of learning and teaching which takes place in each classroom each day. It helps to provide a picture of a child or young person's progress and achievements and identify next steps in learning. Assessment of a learner’s progress and achievement is based on a teacher’s assessment of their knowledge, understanding and skills in curriculum areas. Teachers assess learning using a variety of approaches and a wide range of evidence.

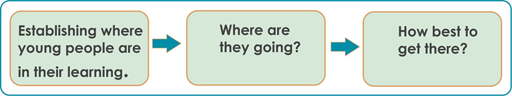

Figure 11 provides an overview of effective ongoing assessment which is about:

The principles for the assessment of additional support needs are no different to those for Curriculum for Excellence. As highlighted in module 2, Section 1.4, literacy, numeracy and health wellbeing are the responsibility of all teachers This means that all staff have a very valid and important contribution to the process of identification and support for dyslexia. The information which is gathered on a daily basis by class teachers as part of their curriculum moderation and assessment will provide a significant contribution to the identification process of dyslexia. This information reflects the learner’s presentation in class and can include examples of:

- Observations

- Pieces of class work – examples of free handwriting to evaluate spelling, structure

- Conversations about text to evaluate reading comprehension

- Comparison of verbal and written ability

- Organisational skills

- A non ‘measurable’ piece of assessment that is recorded can be as important. For example, the learner’s sense of directionality or ability to throw a ball accurately

- Information shared by parents and the learner

Education Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) Statement for Practitioners (August 2016) stated that the two key resources which support practitioners to plan learning, teaching and assessment are the Experiences and Outcomes (Es and Os) and Benchmarks.

4.2. Benchmarks and assessment of dyslexia

The Curriculum for Excellence Experiences and Outcomes support effective planning, learning, teaching and assessment and a collegiate approach to effective moderation of planning learning, teaching and assessment.

Benchmarks support teachers’ professional judgement of a level and this is only achieved through the use of effective moderation of planning learning, teaching and assessment.

Teachers and other practitioners draw upon the Benchmarks to assess the knowledge, understanding, and skills for learning, life and work which learners are developing in each curriculum area. Benchmarks have been designed to support professional dialogue as part of the moderation process to assess where children and young people are in their learning. Importantly, they will help to support holistic assessment approaches across learning and this pedagogy supports the collaborative identification process of dyslexia very well.

Benchmarks for literacy and numeracy should be used to support teachers’ professional judgement of achievement of a curriculum level. In other curriculum areas, Benchmarks support teachers and other practitioners to understand standards and identify children’s and young people’s next steps in learning. Evidence of progress and achievement will come from a variety of sources including:

- Observing day-to-day learning within the classroom, playroom or working area

- Observation and feedback from learning activities that take place in other environments, or on work placements

- Coursework, including tests

- Learning conversations

- Planned periodic holistic assessment