Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 3 May 2024, 6:13 AM

Communicating AMR data to stakeholders

Introduction

This module will encourage you to think about how you can make the biggest impact in communicating

Global action to tackle drug-resistant infections is not happening at the scale and urgency needed. Action can be strengthened with a better recognition and understanding of the problem. Unfortunately, this wider understanding of AMR, AMU and AMC data and their impact is currently limited. We can change this by communicating more widely and more powerfully.

Note that because different stakeholders use different terms, ‘antimicrobial’ and ‘antibiotic’ are used interchangeably in this module.

After completing this module, you will be able to:

- appreciate the ‘bigger picture’ and make the most of AMR, AMU and AMC data

- identify local, national and global ‘AMR networks’ and stakeholders

- recognise different target audiences, and effectively match your communication strategies to each audience

- use a range of communication styles and platforms.

Activity 1: Assessing your skills and knowledge

Before you begin this module, you should take a moment to think about the learning outcomes and how confident you feel about your knowledge and skills in these areas. Do not worry if you do not feel very confident in some skills – they may be areas that you are hoping to develop by studying these modules.

Now use the interactive tool to rate your confidence in these areas using the following scale:

- 5 Very confident

- 4 Confident

- 3 Neither confident nor not confident

- 2 Not very confident

- 1 Not at all confident

This is for you to reflect on your own knowledge and skills you already have.

1 Making an impact with AMR data

Communicating about AMR is a fundamental part of the Global Action Plan on AMR (IACG, 2018), which sets out five strategic objectives as a blueprint for countries developing a

‘Improve awareness and understanding of AMR through effective communication, education and training.’

The annual country self-assessment survey commissioned by the Tripartite – a combination of the World Health Organization (WHO), the

The

1.1 Targeting priorities

Improving the use of antimicrobials through

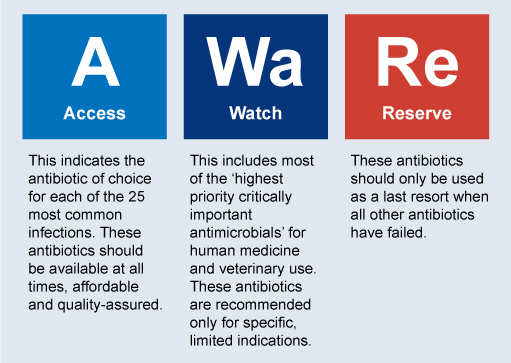

For that reason, WHO in 2017 introduced the Access, Watch, Reserve (

(The concepts of AMU and AMC data, and how each differ, is explained in the Introducing AMR surveillance systems module.)

Quantifying AMU in each of the AWaRe categories allows some inference about the overall quality as well as quantity of AMU. For example, overuse of antimicrobials in the Watch group can become immediately apparent: activities to reduce the use of these antimicrobials and promote the use of drugs in the Access category can be identified as targets for AMS interventions. These trends can be assessed over time to evaluate the impact of the stewardship interventions.

Case Study 1 is a good illustration of how AMS programmes are often initiated in facilities or even countries due to an outbreak of multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Case Study 1: Facility AMS in Barbados (WHO, 2019b)

An outbreak of carbapenemase-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPC) in a 600-bed healthcare facility in Barbados led to an AMS programme being established.

At the time of the outbreak, the facility’s infection prevention and control (IPC) programme consisted of a single nurse; this was later expanded to include an infectious disease physician and a pharmacist. The IPC team used data to demonstrate to the hospital management that an AMS programme was critically needed and that it would involve minimal cost.

Leadership commitment led to establishing an AMS team consisting of an infectious disease physician, a pharmacist and a microbiologist, as well as IPC-trained personnel who were all already employed in the facility.

The AMS set a target for decreasing the overall cost of antibiotics and hospital length of stay over the next six to twelve months. The targets were achieved faster than anticipated, and interest grew from other wards to be included in the AMS programme. A 60% decline in the use of carbapenems and vancomycin was documented.

Case Study 1 demonstrates the importance of communicating AMR and AMU data to improve AMS. The IPC team used data to communicate the need for an AMS programme to hospital management. The AMS programme achieved a 60% decline in use of several Watch antibiotics (carbapenems and vancomycin).

Certain stakeholder groups will play an important role in influencing the use of antimicrobials:

- those who prescribe (such as healthcare workers or veterinarians)

- those who dispense (such as pharmacists, retailers and veterinarians)

- those who consume (such as patients, or farmers treating plant and animal infections).

Each of these groups requires bespoke messaging and targeted strategies. Priority-setting helps to pinpoint where efforts should be focused for the greatest impact and return on investment.

Activity 2: Communication in AMS programmes

1.2 Raising awareness of AMR

Efforts to raise awareness can employ a general strategy to target the public or a focused one to target key stakeholder groups directly engaged in AMR and AMS activities. (IACG, 2018). Public health communication campaigns can have a positive impact in terms of curbing AMU by:

- raising awareness of the growing problem of drug resistance

- reducing patient expectations of providers’ prescribing antimicrobials

- explaining why antimicrobials will not work to address common viral conditions like colds or flu.

One example is the

Examples of campaign materials from WAAW 2020 are available from the WHO’s website (WHO, 2020).

Activity 3: Raising awareness of AMR

Watch the following video produced for WAAW 2020, in which civil society organisations in Africa demonstrate how they have been raising awareness of AMR (ReActTube, 2020).

As you watch the video, list the ways in which stakeholders are being brought together and how communication of data is encouraged .

Answer

Stakeholders are being brought together and communication of data is encouraged by workshops, a webinar series, an AMR desk and campaigning on social networks.

Identifying areas where public or professional knowledge and awareness is lacking and targeting these areas with educational messaging is referred to as a

If you intend to raise stakeholder awareness, sometimes a knowledge deficit model alone is not enough to change behaviours. Research has shown that communications that compare stakeholders with their peers, as opposed to an education-only message, were consistently found to be more effective in reducing prescription rates in the six months after receiving the letter (Australian Government, 2018). The example in Case Study 2 demonstrates how AMU and AMC data can be communicated effectively at a local level to reduce antimicrobial prescribing.

Case Study 2: Nudge versus superbug (Australian Government, 2018)

Behavioural insights were applied to the design of four different letters sent to high-prescribing GPs (specifically, those in the top 30% of prescribers). The letters aimed to prompt GPs to reflect on whether they could reduce prescribing when appropriate and safe.

GPs received one of four different letters: an education letter, or one of three letters with peer comparison feedback.

The education letter simply contained standard information about AMR, and also included two posters from the National Prescribing Service.

The three other letters all began with peer comparison in the first line of the letter, for example:

Your prescribing rate is higher than 91% of doctors in the Canberra region.

These letters provided GPs with information on how their prescribing compared to their peers, to help influence future prescribing. Simple peer comparison feedback like this can be powerful, because we often look to the behaviour of others to guide our own choices. As in this example, letters to individual GPs informed them on AMR, and their prescribing practices compared to GPs in their region, a relevant reference group.

The second peer‑comparison letter also included an eye-catching graph, illustrating the difference between that GP’s prescribing rate and the average for their region.

The third peer‑comparison letter included additional material on wait-and-see prescribing. For example, the idea was that doctors could place delayed prescribing stickers on a script to encourage patients to monitor their symptoms before deciding whether to fill the script.

The first letter reduced prescribing rates by 3.3% over six months, whereas the three peer comparison letters drove prescribing rates down by 9–12% over the same six-month period.

In addition to the examples of awareness campaigns given above, the ReAct toolbox provides inspiration and guidance on what can be done to address AMR (ReAct, n.d.). This online,

1.3 Supporting behaviour change

Public and provider awareness of what a post-antibiotic era would be like can motivate individual behaviour change, and both healthcare delivery and food production systems can provide opportunities for individual practitioners, health workers (animal and human health sectors), and farmers to change their behaviours to improve AMS (IACG, 2018).

Broadly two kinds of intervention have been found to improve prescribing of antibiotics (Davey et al., 2017):

- restrictive techniques – rules-based approaches to improve prescribing

- enablement techniques – advice and feedback approaches to support prescribing.

Activity 4: Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing

Read paragraphs four to eight of the Discussion section in an article about improving antibiotic prescribing practices using a One Health approach in Australia (Zhuo et al., 2018). Complete the following sentences:

Normative guidelines help shape individual practice patterns of healthcare workers prescribing, dispensing and treating patients with antimicrobials and similarly of veterinarians treating diseased animals. This normative guidance comes from a variety of sources:

- expert guidelines from the WHO, the FAO, the OIE,

Codex Alimentarius and other intergovernmental agencies - professional societies at the global and national levels

- disease-specific program initiatives

- country-level initiatives.

One example of a country-level initiative is described in Case Study 3.

Case Study 3: Thailand’s Antibiotic Smart Use project (So and Woodhouse, 2014)

The provincial health office collected data on:

- antibiotic prescription rates

- provider attitudes of effectiveness and knowledge of antibiotics

- non-prescription rates in cases of non-bacterial infections

- patient health and satisfaction.

Antibiotics Smart Use built decentralised networks that engaged local partners to adapt normative guidelines in their own healthcare settings and communities. These local partners comprised of networks of multidisciplinary groups across the healthcare, government and academic sectors, which extended to 22 public hospital systems in 15 provinces.

The network harnesses and shares success stories from local partners within the provider, hospital and pharmacist networks. A sequence of meetings brought together local stakeholders to evaluate the effectiveness of their current approach and to strengthen cooperative efforts. Extending this outreach, seed monies supported data collection and monitoring by hospitals, and training on treatment guidelines increased physician confidence.

The Antibiotics Smart Use project in Thailand shows the interplay between providers and patients, national guidelines and locally inspired efforts to implement them, and incentive systems and culturally mediated interventions. The project reveals the importance of local stakeholder ownership as well as the challenges of sharing and scaling these practices and sustaining such efforts.

Systems-level approaches at the regional/national level require an approach that targets multiple areas. Keys to the success of such interventions are:

- setting incremental targets

- enhancing surveillance

- providing feedback to trigger behaviour change.

Another way to create an enabling environment for behaviour change is to make AMR a core component in the health and veterinary sectors and agricultural practice in:

- professional education

- training

- certification and credentialing

- continuing education.

The WHO Competency Framework for Health Workers’ Education and Training on Antimicrobial Resistance aims to strengthen efforts at the country level by outlining basic AMR competencies to guide the education and training of health workers (WHO, 2018a). The framework is aimed at institutions involved in pre-service and in-service training and education, as well as accreditation and regulatory bodies and policy- and decision-making authorities.

Collecting AMR, AMC and AMU data, and using this to provide tailored feedback and education to key stakeholders, is fundamental in achieving behaviour change and reducing inappropriate prescribing of antimicrobials. The framework can be used to design audit and data collection to support these aims.

Activity 5: A collaborative project

1.4 Monitoring for accountability

As key stakeholders begin to take collective action, monitoring for accountability adds another important dimension to communicating about AMR. Monitoring for accountability is not just a role for governments; it can also engage key stakeholders from industry to civil society.

Effectively monitoring processes and outcomes provides the necessary feedback loops to optimise approaches for maximum impact and resource efficiency. Such monitoring can not only hold stakeholders accountable to commitments made and outcomes, but also ensure sustainability of these actions.

Data becomes actionable when it allows for comparisons and trend analysis, flags outliers in performance, or benchmarks against standards. Such approaches enable data analysis to serve as a trigger for policy action. Change can result from continuous quality improvement, ‘carrot or stick’ enforcement, and/or effective governance structures.

This process of monitoring for accountability can be conceptualised in several stages, such as the 3Cs:

- collecting data

- comprehending these findings

- compelling policy-makers with the findings.

By supporting institutions that enable the 3Cs, monitoring for accountability can serve the critical function of benchmarking progress towards the future vision laid out by the IACG’s recommendations (2018). These institutions might be governmental or non-governmental:each will have its own strengths and limitations, but collectively, these might comprise a global watch of actions against the spread of AMR.

India is an example at the national level because it has successfully integrated environmental standards into its NAP, which will serve as a basis for monitoring and accountability (WHO, 2017a). Environmental concerns are highlighted in three of the six overarching priorities, which include environment-specific interventions and target outputs. Reducing the environmental spread of AMR is one of four goals in the NAP strategic priority (‘reduce the incidence of infection through effective infection prevention and control’).

Groups like the Delhi-based Centre for Science and the Environment played a key role in advancing environmental concerns into NAPs on AMR.

Industry has taken initial steps towards collective action on this as well. In 2018, an international private sector coalition published a progress report noting that, of the 36% of companies contacted that responded (AMR Industry Alliance, 2018):

- all were reviewing operations of suppliers to reduce environmental discharge

- a majority were improving oversight or setting standards into supplier contracts

- nearly 40% were increasing public transparency of their findings regarding these suppliers.

2 Finding stakeholders

With root causes in sectors ranging from health, food safety and agriculture to environment and trade, AMR is one of the most complex public health threats the world has faced (WHO, 2018b). No single government department or independent organisation can tackle it alone. Containing and controlling AMR demands coordinated action across diverse sectors and disciplines, with a broad range of stakeholders.

In the previous section you saw plenty of examples of the types of organisations and individuals that are interested in AMR. In this section, we are going to look at those networks of AMR stakeholders in more detail and think about how to effectively use the networks to communicate AMR data.

2.1 Identifying key stakeholders

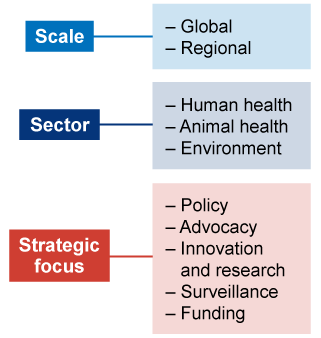

An effective way to identify the current key actors in the field of AMR is through

The international independent network for action on antibiotic resistance,

Global and regional AMR stakeholders

A number of organisations are working to address AMR globally, with a broad remit. Table 1 lists some key global stakeholders that focus (with the exception of the Tripartite) exclusively on AMR. This table is not an exhaustive list, and you should also be aware that many larger organisations (for example the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, or the Wellcome Trust) may also have significant AMR programmes within their overall scope of work.

| Stakeholder | Sector | Strategic focus |

|---|---|---|

| Tripartite Collaboration (WHO, FAO, OIE) | Human health, animal health, environment | Policy |

| ReAct | Human health, animal health | Advocacy |

| Antibiotic Resistance Coalition (ARC) | Human health, animal health, environment, One Health | Advocacy |

| World Alliance Against Antibiotic Resistance (WAAAR) | Human health, animal health, environment, One Health | Advocacy |

| The AMR Industry Alliance | Human health, environment | Advocacy |

| Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP) | Human health | Innovation and research |

| Community for Open Antimicrobial Drug Discovery (CO-ADD) | Human health | Innovation and research |

| Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) | Human health, One Health in the near future | Surveillance |

| Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (GASP) | Human health | Surveillance |

| The Fleming Fund | Human health, animal health, One Health | Funding |

| The Global AMR Innovation Fund (GAMRIF) | Human health, animal health, One Health | Funding |

| AMR Action Fund | Human health, animal health, One Health | Funding |

Funding for surveillance is not always a priority of national governments, particularly in LMICs. In these cases, AMR stakeholders that work in the region can help to address AMR. Some international initiatives offer financial and technical support for building laboratory and surveillance capability in these countries; for example, initiatives supporting the surveillance elements of the Global Health Security Agenda, the Fleming Fund and the World Bank’s Regional Disease Surveillance Systems Enhancement programme, which supports countries in the Economic Community of West African States in strengthening national surveillance systems and intercountry collaboration.

Additional regional AMR stakeholders are listed by sector and strategic focus in Table 2.

| Stakeholder | Sector | Strategic focus | Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) | Human health | Policy | South-east Asia |

| Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance (JPIAMR) | Human health, animal health, environment, One Health | Innovation and research | Europe |

| Asian Network for Surveillance of Resistant Pathogens (ANSORP) | Human health | Surveillance | South-east Asia |

| Partnership for AMR Surveillance Excellence (PARSE) | Human health, animal health | Surveillance | Africa and Asia |

National AMR stakeholders

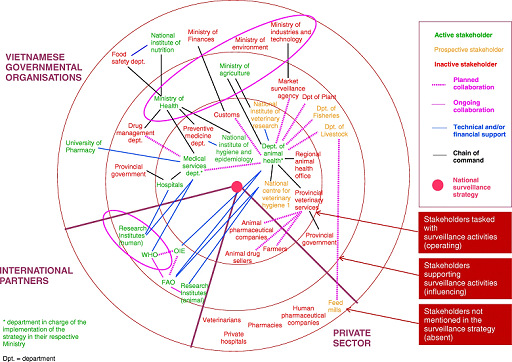

Detailed stakeholder mapping can also be undertaken at the national level. Figure 4, an iterative stakeholder mapping and analysis exploring the role of key stakeholders in Vietnam’s AMR surveillance strategy, is a good example (Bordier et al., 2018).

The mapping and analysis shown in Figure 4 was conducted in three stages:

- A description of the structure of the national surveillance strategy in conjunction with international recommendations (based on a literature review and key informant interviews).

- An analysis of the key stakeholders’ positions regarding the strategy (based on semi-structured interviews).

- Identifying factors influencing the operationalisation of the collaborative surveillance strategy.

Activity 6: Stakeholder mapping

Study Figure 4 in detail. Make a list of the stakeholders that you would need to include if you were tasked to create a similar map for your own country, and group them into types. (You may pick a different aspect of AMR other than surveillance, if you prefer.)

Think about what other information you would need in order to construct such a map, and where you could find it.

2.2 Engaging with AMR stakeholders

In the previous section we identified global, regional and national level AMR stakeholders. In this section, we are going to have a more detailed look at some of those stakeholders and consider how best to engage with their work. The three organisations or initiatives discussed below each cover a different strategic focus:

- advocacy

- innovation and research

- surveillance.

Advocacy: ReAct

Background

ReAct was initiated with the goal to be a global catalyst, advocating and stimulating global engagement on AMR by collaborating with a broad range of organisations, individuals and stakeholders.

It is set up as a network of five regional offices (‘nodes’) located in Ecuador (Latin America), India (Asia Pacific), Zambia (Africa), the US (North America) and Sweden (Europe). Each node is hosted by an institution such as a civil society organisation or a university that assists with most legal, economic and HR issues.

How does ReAct support communication?

ReAct shares and generates knowledge on AMR, including the compilation of scientific evidence, collecting in-country experiences and best practice methodology. More information can be found on its website and in its toolbox (see Section 1.2).

ReAct acts as a knowledge repository and resource centre, providing tools to help different types of stakeholder to:

- understand key AMR concepts

- collect and analyse AMR and AMU data

- present and communicate information and data.

ReAct Africa holds an annual conference (ReAct, 2019; see Activity 3) that brings together key people from multiple countries to share experiences and best practices, but also the obstacles and failures, to support each other.

ReAct is an independent network and has built a reputation for scientific credibility and lack of bias. This means that stakeholders are more likely to trust its information, as it is not influenced by industry or governments.

Innovation and research: JPIAMR

Background

The Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance (JPIAMR) is a global collaborative platform, engaging 28 member nations to curb AMR with a One Health approach. The initiative coordinates national funding to support transnational research and activities within the six priority areas of the shared JPIAMR Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda:

- therapeutics

- diagnostics

- surveillance

- transmission

- environment

- interventions.

JPIAMR-Virtual Research Institute (VRI)

The JPIAMR is currently developing a platform to extend shared research capabilities on a global scale through the Virtual Research Institute (JPIAMR-VRI). This virtual platform will:

- increase coordination

- improve visibility of the AMR research networks

- research performing institutes/centres and infrastructures

- facilitate knowledge exchange and capacity development across the globe, covering the full spectrum of concerned sectors and taking a One Health approach where appropriate.

For further information, the video describes the remit and goals of the JPIAMR-VRI Network CONNECT, which is the main VRI network devoted to communication (JPIAMR, 2019):

JPIAMR networks and communication

The JPIAMR has funded several networks to promote and support the development of AMR programmes, such as the Network for Enhancing Tricycle ESBL Surveillance Efficiency (NETESE).

‘Tricycle’ is an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-Escherichia coli surveillance program developed by WHO to obtain a global picture of AMR in humans, animals and the environment in multiple countries, especially in those with limited surveillance capacities. Countries are at different stages of initiating or preparing for Tricycle, and NETESE was developed to assist in linking early-implementing countries together for exchange, mutual support and experience sharing.

Currently, NETESE includes 15 institutions from nine LMICs at different stages of implementation of Tricycle. Regular meetings and web-conferences gather participants together to share their experience, present data and discuss dedicated topics of interest. By sharing information in this way, NETESE aims to become a sustainable network and resource centre where countries implementing Tricycle can find support and experience.

The following video describes the JPIAMR NETESE in all three sectors in nine LMIC countries (JPIAMR, 2020):

NETESE and the JPIAMR-Virtual Research Institute (VRI) provide good examples of communication between similar stakeholders. These types of networks and communication are important in ensuring that available resources are used optimally: by minimising duplication of effort, helping to harmonise data collection so that results are comparable, and allowing stakeholders to share learning and experience.

Surveillance: GLASS

Background

The

GLASS encourages and facilitates the establishment of national AMR surveillance systems that are capable of monitoring AMR trends and producing reliable and comparable data.

How GLASS encourages the communication of AMR data

(GLASS is covered in detail in the Introducing AMR surveillance systems and An overview of national AMR surveillance modules.)

The GLASS objectives are to:

- foster national surveillance systems and harmonise global standards

- regularly analyse and report global data on AMR and AMU

- estimate the extent and burden of AMR globally by selected indicators

- detect emerging resistance and its international spread

- inform implementation of targeted prevention and control programmes

- assess the impact of interventions.

One of the key outputs from GLASS is its annual (and publicly available) report on surveillance data. The report contains information on surveillance system status as well as data on key pathogens and resistance patterns. Because the data is presented in the same format for each country, stakeholders can easily see how their system, and the data it produces, compares with others across the world. Standardising data in this way makes it a highly effective way of communicating data at the global level.

Although initially GLASS focused on AMR data, the system is expanding to address consumption and use to obtain and share standardised data at the global level.

Activity 7: International AMR networks and stakeholders

3 Understanding your audience

When you begin preparing to communicate, you should be thinking about who your audience is. Put yourself in their shoes.

- The general public is interested in how your research affects their lives or society today, tomorrow or in ten years’ time.

- Funders are usually interested in how they may get a return on their investment.

- Your peers will want to know more about how you work, what your findings are and the possibility for future collaborations.

- Industry partners will look for technologies that can help propose products or services that will become a commercial success.

Make sure you understand what your audience is interested in, and adapt your communication accordingly.

Science communication is often based on specific research outputs – usually technical journal articles. However, the best science communicators find a way of placing technical research in a larger narrative context: they tell a story. Sometimes, the most effective way to tell a science story is to focus on the process.

The difference between a good science story and a great one often comes down to the quality of its visual assets. The best science stories are truly immersive, with rich photography, videos or illustrations, and sometimes other visual effects.

In the previous section you saw examples of AMR stakeholders at the global and regional level, and how they can be mapped at the national level. These stakeholders could be categorised by their strategic objectives, which included:

- policy

- advocacy

- innovation and research

- surveillance.

In this section we are going to consider how stakeholders involved with advocacy and innovation & research communicate with their audiences. Stakeholders involved with policy will be covered in the AMR data for policy-making module. Stakeholders involved in surveillance are covered in the Sampling (human health) and Sampling (animal health) modules.

3.1 Advocacy

Global action to address drug-resistant infections is not happening at the scale and urgency needed. Action among political leaders can be strengthened with public support. But public understanding of AMR and its impact is currently limited.

Advocacy aims to change this by communicating more powerfully to increase public comprehension and persuade the public and policy-makers of the case for action on AMR.

A Wellcome Trust study

The Wellcome Trust conducted a study to identify the most effective ways of framing the issue of AMR (Wellcome, 2019). The study involved:

- in-depth interviews with experts

- quantitative and qualitative message testing with 12,000 people in Germany, India, Japan, Kenya, the UK, the USA and Thailand

- media and social media analysis.

The study showed that there are universal themes that can be used effectively across countries. It identified five principles for communicators when talking to the public about AMR, and encourages experts and practitioners working on AMR to use these principles to inform public communications:

Frame AMR as undermining modern medicine

Framing the issue as undermining modern medicine helps the public understand the breadth of the impact that AMR currently has and could have in the future. This should be coupled with examples of routine procedures and common illnesses and injuries that could be affected by AMR.

Explain the fundamentals succinctly

Simple, straightforward and non-technical explanations of AMR are necessary and effective in increasing understanding of the issue. It is important that we explain that microbes develop resistance, not individuals, and also that our explanations include the part that human activity is playing in accelerating the issue.

Emphasise that this is a universal issue

Explain that this is a universal issue that anyone could be affected by. We need to increase the sense of personal relevance, and responsibly highlight the risk that AMR poses to all.

Focus on the here and now

Make it clear that AMR is currently having a significant impact – and that this impact will become increasingly severe if action is not taken. This is more effective than pointing to what could happen in five or ten years’ time.

Encourage immediate action

We can boost the impact of communications on AMR by framing the issue as solvable. Crucially, this needs to be accompanied by a clear and specific call to action.

Insights from an online discussion

An online discussion, ‘Improving communications for Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) in Africa: How should we move forward?’, was held on the FAO’s Global Forum on Food Security and Nutrition in June 2020 (FAO, 2020a).

This online discussion invited participants to exchange ideas and discuss how to improve communication about AMR and involve necessary stakeholders, thus ensuring that this important issue becomes a top priority in national and regional development agendas. A summary of the discussion questions and participants’ contributions is provided below:

What is the biggest communication challenge related to AMU and inappropriate AMU in Africa?

- Stakeholders find it difficult to relate to the risks associated with AMR.

- Farmers don’t consider AMR to be part of their lived experience.

- Communications about AMR aren’t relatable to those most affected by it.

- The threat of AMR needs to be strongly emphasised and communicated as a problem of high urgency.

What is the best approach to communicate about other antimicrobials, and not only antibiotics?

- The one-size-fits-all approach does not work in all contexts.

- Different communication strategies are required to capture the attention of different groups of stakeholders.

- Tips: keep the message simple; use the term AMR consistently; make AMR more relatable and tangible as an issue; target the communication; multisectoral collaboration; engage journalists; physical workshops; link the communication clearly to the desired behaviour change.

What communication channels, methods or mechanisms are more suitable and will have the greatest impact at field level in African countries?

- Make use of both traditional and modern media.

- Social media can reach out to the younger generation of farmers and health workers, and can connect with food consumers.

- Traditional communication channels, especially radio programming, are an effective way of reaching people in more remote rural areas.

- It is important to make use of cross-cutting, multi-stakeholder initiatives such as the African Union’s One Health approach.

Which group of stakeholders do you think should be considered a priority for targeted key messages aimed at raising awareness on excessive AMU and AMR?

- Farmers are the key stakeholders to reach by AMR communication campaigns and are not currently being reached.

- Veterinarians and pharmacists should be given particular focus, due to their crucial role in drug prescriptions and sales, which puts them in a unique position to convey information to farmers.

- AMS programmes aimed at educating medical personnel to follow evidence-based prescriptions need to be set up in order to stem antibiotic overuse.

Activity 8: Communication principles

Think of a time when you have been involved in communicating with the public about AMR, either as a participant or in the audience. As far as you can remember, how far did that event follow Wellcome’s five principles? Can you think of how it could have been improved?

3.2 Innovation and research

Innovation and research are critically important in the field of AMR, as there is a strong need for new therapeutics, diagnostics and innovative infection prevention and intervention measures. Understanding how to communicate with these stakeholders is valuable for furthering research and innovation in the area of AMR you are interested in.

Several research and development initiatives address AMR for human health and very few for animal health. In human health, several international initiatives have been launched to stimulate research, including:

- Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance (JPIAMR)

- Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X)

- New Drugs for Bad Bugs (ND4BB)

- Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP)

- Novo REPAIR Impact Fund.

There are fewer global research and development initiatives in animal health, and they are less likely to have a specific focus on AMR:

- GALVmed

- Livestock Vaccine Innovation Fund.

These initiatives operate with limited budgets and contribute to the response to research and development challenges.

In this section we will take a deeper look at how JPIAMR and GALVmed are supporting and promoting innovation and research in AMR. We will also consider how best to engage with each organisation.

JPIAMR

The JPIAMR is a global collaborative platform that coordinates national funding to support transnational research and activities. It has so far supported 61 projects and more than 340 research groups across 38 networks, with funding of approximately €80 million.

The JPIAMR is mapping AMR research funding continuously and has created an interactive dashboard that:

- provides an overview of the grant investments and research capacities

- visualises key data on how to invest in AMR research

- allows users to examine national competitive grants data (institutional funding is not included) by agency, country, AMR research priorities and individual research projects.

The JPIAMR is engaged in a series of dialogues worldwide to share and exchange ideas and information with nations committed with the AMR challenge and willing to coordinate their research actions addressing AMR. New members who share the JPIAMR’s vision are encouraged to join and participate in collaborative actions and in funding multinational and multi-disciplinary research.

On the JPIAMR website you can find details of:

- events – the JPIAMR organises scoping workshops and strategic workshops, as well as policy workshops aiming knowledge translation and foresight

- JPIAMR-VRI, which supports the AMR scientific community by:

- improving the visibility of the AMR research networks

- researching performing institutes/centres and infrastructures

- facilitating knowledge exchange and capacity development.

These are two important tools for engaging with JPIAMR and utilising the platform.

GALVmed

GALVmed’s research and development specialises in product development partnerships uniquely established to translate publicly and privately funded research into tangible livestock disease control tools for use by small-scale livestock keepers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Since its inception, GALVmed has worked on 13 priority diseases that have been identified as imposing severe constraints on small-scale agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia.

GALVmed maintains a small research and development team that works through an extensive network of partners comprising contract research organisations (CROs), commercial and academic laboratories, research institutes and quasi-governmental organisations. A broad range of research and development activities take place through these partners; components of this work include:

- drug discovery

- formulation science

- technology assessment

- antigen identification

- biological process enhancements

- clinical studies for product registration

- epidemiological investigation.

Within the full range of activities above, the broad focus of GALVmed’s research and development work is on the translation of outcomes from basic research through to product development, registration, manufacturing and commercialisation. The GALVmed website provides information on the programmes it has helped to deliver; reading these will give an insight into GALVmed’s work and how to engage with the organisation.

4 Choosing the right platform

Articles, conference talks and the press are the ‘traditional’ tools for communicating science; in the twenty-first century, digital tools such as social media, blogs or videos have evolved to become important communication channels.

These are not only a fantastic way to communicate to the general public; they also provide the opportunity to exchange with fellow researchers and build scientific communities. When communicating, you should think about combining traditional tools with newer ones. This will allow you to communicate in an interesting and dynamic way, broadening your audience’s experience.

In this section, you will learn how to identify effective channels of communication and see examples of how these non-traditional communication platforms are used.

4.1 Matching the platform to the audience

You need reliable channels for reaching decision-makers, disseminating messages and distributing materials. To identify the best available messaging pathways, you should analyse the audience’s access to different channels and their preferences.

When developing communications strategies, you should consider a channel’s reach and influence (WHO, 2017); for example:

- mass media channels such as radio, community billboards and posters on public transportation have broad reach and can increase issue awareness

- local radio can be a good channel for disseminating urgent public health information in specific locations

- interpersonal channels are especially important when trying to influence attitudes and encourage wider adoption of health behaviours.

Global communication channels

Global communication channels are useful for reaching broad groups of audiences with high level messages. Examples include the following:

- International news media, such as researchers from Imperial College London using European Scientist to publicise their recent research (Sabnis et al., 2021) in a news article (Reis, 2021).

- Websites, such as creating your own research group/company website, utilising the websites of global AMR stakeholders. Examples include the International Livestock Research Institute or the AMR Industry Alliance.

- Social media platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Google+, Instagram, LinkedIn and Foursquare. Examples of Twitter accounts include CGIAR_AMRhub, OIE Animal Health and Investor Action on AMR. Examples of YouTube accounts include the WHO, the Global Respiratory Infection Partnership (GRIP) and the GARDP.

Placement through these channels may be free or may incur a cost, if placement on certain platforms or at specific times is important.

Regional and national communication channels

Regional and country-level channels have the advantage of better targeting and reaching audiences geographically, and are better able to bring tailored information to the attention of specific audiences with particular interests. Examples include the following:

- Regional, national and local news media.

- Social media accounts with regional and local followers, such as ReActTube, Community Engagement for AMR or Students Against Superbugs Africa

- Websites, such as creating your own research group/company website, utilising the websites of regional AMR stakeholders. Examples include the WHO Regional Office for Africa, African Association for Research and Control of Antimicrobial Resistance and the OIE Regional Representation for Asia and the Pacific.

- Networks of local organisations.

- Interpersonal and community networks.

These channels are more effective at disseminating information, advice and guidance for local audiences to use. They can reach specific groups of individuals based on geography (even down to the village level) or a common interest, such as occupational status. Channels may include community-based media (such as local radio talk shows or organisation newsletters), community-based activities (such as health fairs), and meetings at schools, workplaces and places of worship.

You can tailor consistent messages aimed at different audiences and distribute them through global, regional and country levels to ensure broad dissemination of information that is actionable at different locations and levels.

Interpersonal communication channels

One-to-one discussions are often the most trusted channels for health information. People seeking advice or sharing information about health risks often turn to:

- family

- friends

- healthcare practitioners

- co-workers

- teachers

- counsellors

- faith leaders.

Collaborating with individuals and partners who share your communication objectives is particularly important when they have existing trusted relationships with key audiences.

4.2 ‘Non-traditional’ platforms

Social media

Many networking opportunities today are online, through social media websites. Having a presence on these sites can help you to:

- facilitate discussions with your colleagues

- assist you in staying abreast of the latest research

- help you to perform science outreach.

There are also academic and professional social networking sites such as Academia.edu and ResearchGate that have grown rapidly, with researchers sharing their work and being able to track work by people that they follow.

The key to being successful in maintaining an online presence, whether for outreach or for networking, is to find the platform or platforms that fit your needs. Table 3 will help you think about which social media platforms are best suited to your communication goals.

| Platform | Description | Your goal | Time commitment | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A social networking site for 280-character messages (tweets). You can ‘follow’ the tweets of your friends or colleagues, and even those of strangers and celebrities. | To send messages or publicise content in 280 characters or less; to stay up-to-date with the news, discussions and issues in your field, and join in fast, pithy conversations. | Medium; aim to tweet almost every day to keep your account active. Serious Twitter users will tweet multiple times a day. | An easy way to connect with diverse people in your field; the ability to share information and follow news in real time. | The fast pace can be overwhelming, and tweets can get ‘lost’ in the crowd. | |

| A social networking site that allows you to post photos, videos, links and messages to your profile. Pages can be created by companies, laboratories or research groups, and followed by anyone. | To share relevant links and information that your audience is interested in. | Low; post links or original content a few times a week. | A familiar platform for most people, with (theoretically) a large audience. A Facebook page for a laboratory group can let you reach people without using your personal account. | It takes a lot of work to reach people outside of your Facebook ‘friends’, so reaching a wider audience can be difficult. | |

| Platform | Description | Your goal | Time commitment | Pros | Cons |

| The world’s largest online professional network. You can build your network by adding professional contacts, and can also follow people, companies or topics. You can create and join professional events, and share your perspective on relevant issues and topics with others. | To advance your career and tap into a network of professionals, companies and groups within and beyond your industry. | Low/medium; ideally, post a few times a week. Creating your profile and building your network can take time. | LinkedIn builds strong networking opportunities, allows you to link your accounts and blogs to share experiences and advice on topics that are important in your industry, and allows people to share their expertise to help others. | It is initially time-consuming; you will need to spend some time building your profile by familiarising yourself with the site’s features and making connections. It has limited interactivity compared with Facebook or Twitter. | |

| Blogging (e.g. with WordPress, Blogger or Tumblr) | Writing and posting content on a dedicated website. Think of it like public journaling on a certain theme (such as marine science, the nitrogen cycle, being a PI, etc.) | To share your thoughts throughout the creation of in-depth, original content. Tumblr is different in that it is primarily image-focused. | High; posts can take anywhere from 30 minutes to many hours, depending on the topic. Posting at least once or twice a week is important for maintaining an audience, but prolific bloggers post most days. | It can reach a wide audience, and works synergistically when promoted through other social media; it has a lasting impact, because posts are available online indefinitely. | It requires a large time investment, especially initially when setting up the website. |

| Platform | Description | Your goal | Time commitment | Pros | Cons |

| A social networking site focused on sharing images and short videos. | To share original images of life in the lab, field or classroom. | Low; ideally, you should post a few times a week. | Visuals can interest a wide audience; it can be used synergistically with other social media. | It may be difficult to regularly update with new photos; there is little opportunity for in-depth interactions with your audience. | |

| Video-sharing (YouTube, Vimeo) | Video-sharing websites where users can upload original videos and watch videos that others have created. | To create and share videos about your research, your lab/field work, or about science in general. | High; although people don’t expect you to post videos all the time, creating high-quality videos takes work. | The potential to reach a wide audience that isn’t otherwise interested in science; once created, a video will be viewed for years to come. | High initial time investment; creating high-quality videos requires equipment and editing software. |

| Platform | Description | Your goal | Time commitment | Pros | Cons |

| A social networking and news website where users submit content and links, and engage in online discussions. | To provide scientific expertise and discuss science issues with scientists and non-scientists alike. | Low/medium; commenting takes little time commitment – setting up an ‘ask me anything’ (AMA) takes more time, but is a one-time thing. | You can reach a large audience; the community is relatively informal and consistent engagement isn’t necessary to have an audience. | In gigantic comment threads, your voice might get buried underneath other comments. |

Tips for using Twitter, Facebook and blogs effectively

- Tweet often. To maintain an active Twitter account, try to tweet every day.

- Use hashtags (a ‘#’ symbol at the start of a word or phrase) to highlight topics, comment on other people’s tweets and respond to comments.

- You can live-tweet events such as workshops, seminars and conferences by tweeting what’s going on using relevant hashtags.

- Use the website Bitly to shorten links.

- Use the Tweetdeck or Hootsuite apps to manage multiple Twitter accounts, schedule tweets and search tweets easily.

- Setting up a Facebook Page for your lab or organisation is a great way to reach people without needing to post things from your personal profile.

- Make sure your posts and links are appropriate for your audience. If your Facebook friends are mostly non-scientists, links to journal articles are probably not going to interest many people.

- Be sure to respond to comments that people make on your posts. Start a conversation.

Blogging

- Blogging successfully requires more thought than some other social media platforms, but its permanence and reach can make it more rewarding as well.

- Figure out who you want your audience to be. Write with them (and their interests, education level, etc.) in mind.

- Decide on a theme for your blog and (mostly) stick to it. The theme can be as general as ‘AMR’ or as narrow as ‘preserving antibiotics through safe stewardship’, but a theme gives your blog coherence and helps to build your audience.

- Make sure that your blog site is visually appealing. Even if you have great content, if your website looks cluttered and distracting, people are likely to click away without reading your posts. Generally, minimalism and simplicity should be your bywords.

- Promote your blog on other social media sites, such as Twitter, Facebook or Instagram. You can make social media accounts for your blog, which works especially well if the blog is a group effort.

Visual communication strategies

Other creative strategies beyond the written word, have been used to communicate about AMR. Some recent examples are listed below (and note that watching the videos is optional).

The Government of Ghana commissioned Ghana’s National Dance Company to create a musical production to educate communities about AMR (Wellcome Trust, 2019):

The WHO creates video content to increase awareness of AMR (World Health Organization African Region, 2021) …

… as does the GARDP (2020):

The International Veterinary Students’ Association (IVSA) Rampur uses YouTube, Facebook and Instagram, creating awareness videos (nvsa rampur, 2020a) …

… and podcasts (nvsa rampur, 2020b):

5 End-of-module quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of this module and can now do the quiz to test your learning.

This quiz is an opportunity for you to reflect on what you have learned rather than a test, and you can revisit it as many times as you like.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window by holding down ‘Ctrl’ (or ‘Cmd’ on a Mac) when you click on the link.

6 Summary

In this module you have learned how to strategically communicate about AMR, from targeting priorities to raising awareness and supporting behaviour change. You have explored the different AMR stakeholders, and how you can identify and engage with them. You have considered different types of audiences and how to effectively communicate with each. And you have looked at a wide range of available communication platforms, and their advantages and disadvantages. Throughout the module you have seen plenty of communication examples relevant to human and animal health.

You should now be able to:

- appreciate the ‘bigger picture’ and make the most of AMR, AMU and AMC data

- identify local, national and global ‘AMR networks’ and stakeholders

- recognise different target audiences, and effectively match your communication strategies to each audience

- use a range of communication styles and platforms.

Now that you have completed this module, consider the following questions:

- What is the single most important lesson that you have taken away from this module?

- How relevant is it to your work?

- Can you suggest ways in which this new knowledge can benefit your practice?

When you have reflected on these, go to your reflective blog and note down your thoughts.

Activity 9: Reflecting on your progress

Do you remember at the beginning of this module you were asked to take a moment to think about these learning outcomes and how confident you felt about your knowledge and skills in these areas?

Now that you have completed this module, take some time to reflect on your progress and use the interactive tool to rate your confidence in these areas using the following scale:

- 5 Very confident

- 4 Confident

- 3 Neither confident nor not confident

- 2 Not very confident

- 1 Not at all confident

Try to use the full range of ratings shown above to rate yourself:

When you have reflected on your answers and your progress on this module, go to your reflective blog and note down your thoughts.

7 Your experience of this module

Now that you have completed this module, take a few moments to reflect on your experience of working through it. Please complete a survey to tell us about your reflections. Your responses will allow us to gauge how useful you have found this module and how effectively you have engaged with the content. We will also use your feedback on this pathway to better inform the design of future online experiences for our learners.

Many thanks for your help.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was collaboratively written by Alana Dowling and Clare Sansom, and was reviewed by Siddharth Mookerjee, Claire Gordon, Joanna McKenzie and Peter Taylor.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Module image: AlexRaths/iStock/Getty Images Plus.

Figure 1: IACG, 2018.

Figure 2: Adopt AWaRe, https://adoptaware.org/. This file is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO) Licence (https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-nc-sa/ 3.0/ igo/).

Figure 3: based on ReAct, 2016.

Figure 4: Bordier et al., 2018. This file is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by/ 4.0/).

Text

Section 1.1, Activity 2: Junaid et al., 2018. This file is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) Licence (https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-nc/ 4.0/).

Section 3.1, ‘A Wellcome Trust study’: Wellcome Trust, 2019.

Section 3.1, ‘Insights from an online discussion’: adapted from FAO, 2019. This file is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO) Licence (https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-nc-sa/ 3.0/ igo/).

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.