Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 March 2026, 7:47 AM

2 The impact of Parkinson’s

2.1 Introduction

Having worked through Section 1 you have a general understanding of what parkinsonism is, what Parkinson’s is, their causes, how many people have Parkinson’s and the average age at which they are diagnosed. You also now know how Parkinson’s is diagnosed and how it progresses.

In this section we look at the following questions:

- How can I help people with Parkinson’s manage their symptoms?

- What impact does Parkinson’s have on people’s daily life?

This section starts with a short video recorded by Tracy Jack. In the video, Tracy introduces herself, where she works and what she gained from doing this course. She also talks about the impact of Parkinson’s on the daily lives of the people she works with, and looks at how the course has helped her develop her own practice.

Transcript

[Music playing]

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

Learning outcomes

The purpose of Section 2 is to give you an understanding of the impact that Parkinson’s can have on an individual and their loved ones. We will discuss both the motor symptoms and non-motor symptoms, and how they can be managed.

By the end of this section you should be able to identify and describe:

- the common challenges that the main motor and non-motor symptoms present to a person with Parkinson’s

- how Parkinson’s can fluctuate and how this impacts on the person living with the condition

- the ways in which these challenges can impact on a person’s quality of life

- how Parkinson’s can affect a person’s relationship with their loved ones

- how a person’s preferences are taken into account when supporting them to manage their Parkinson’s.

2.2 How can I help people with Parkinson’s manage their symptoms?

Exercise 2.1 Symptoms of Parkinson’s

Think about what you learned in Section 1 and the people with Parkinson’s that you have met through your job or personal life. If you were going to meet a person with Parkinson’s for the first time, what would you expect to see in terms of signs and symptoms? Use the reflection log to write down as many signs and symptoms as you can.

Discussion

You may have considered some of the following:

- signs and symptoms differ from person to person

- the severity of symptoms will depend on the phase of Parkinson’s and how well the condition is being managed

- symptoms may change from day to day, and even hour to hour

- the three main motor symptoms of Parkinson’s are resting tremor, rigidity (stiffness) and slowness of movement – people with Parkinson’s will have at least two of these three symptoms

- there are many non-motor symptoms that can have a huge impact on the day-to-day lives of people with the condition, including tiredness, pain, memory problems, depression and constipation.

Additional symptoms not mentioned in Section 2 that you may have written down include:

- shuffling gait

- slowness of thought (bradyphrenia)

- ‘freezing’ when making a movement like walking

- sleep problems, pain, bladder and bowel problems, eating and drinking difficulties, swallowing and saliva problems, speech and communication problems, handwriting problems, falls, loss or change in ability to taste or smell, change in weight, excessive sweating, or double vision

- depression, anxiety, mood and memory problems, Parkinson’s dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, or hallucinations/delusions

- dyskinesia, impulsive and compulsive behaviour, switching ‘on/off’, wearing off, or medication side effects.

This is not an exhaustive list and you may have noted specific symptoms that fit into a category. For example, you may have listed ‘nocturia’ (waking up at night with the urge to urinate) as a sleep problem.

In Section 1 we discussed the main motor symptoms of Parkinson’s – tremor, slowness of movement and rigidity. In this section, we will discuss what you can do to help people who may be living with these symptoms. We will then discuss the non-motor symptoms that people may experience and how they can be managed. This guidance will let you know what you can do to make daily life easier for people with Parkinson’s.

2.3 Helping to manage slow movements (bradykinesia)

It might be hard for a person with Parkinson’s to move as quickly as they want to, which can be frustrating for them. Their ability to move might change very quickly, so at times they can move well, but within minutes they might slow down or stop. It’s important to remember that people are not being difficult when this happens.

People with Parkinson’s are sometimes referred to as having a shuffling gait. This is when a person doesn’t walk with a smooth motion and it may look like their feet are sticking to the floor.

Transcript

Let's take a look at this gentleman as he gets up out of his chair and walks around the room.

To be able to get out of his chair, he has to shuffle forward and start to press down on his hands to be able to gain the momentum to stand upright.

He's a little unsteady on his feet, so he does reach out for his walker to aid with his balance.

Now let's have a look at this walking.

As you can see, his stride length is quite good, and he is quite steady.

He's been asked now to turn a corner, and as you can see, he lifts his walker up, turns his upper body first, and then moves his legs and feet into the same direction.

As he walks across the room, you can see he's not quite picking his feet up.

His fronts of his feet are sliding along the floor and really, it's more of a shuffling step, than a full stride, that you and I would have.

Now he's going to walk independently.

Initially, he loses his balance, but can you see how much smaller his stride length is when he's walking independently?

He's not as confident or comfortable walking without his aid.

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

Actions to take

- Give the person plenty of time, support and patience.

- Keep in mind that they may have trouble getting up from a chair or find it hard to turn over in bed. They might also lack coordination in their hands.

- Remember that a person may be experiencing a loss of facial expression, so don’t assume they are unhappy.

- Some people may find it helpful to use walking aids. Before using any equipment, a person with Parkinson’s should get advice from a physiotherapist or occupational therapist who can assess their needs and make appropriate suggestions.

- Remember that it might also take them longer to answer questions because of speech and swallowing problems related to slow movements or bradyphrenia (slowness of thought).

2.4 Helping to manage tremor

Tremor is one of the main symptoms of Parkinson’s. However, not everyone will develop it – approximately 70% of people with Parkinson’s experience this symptom. A tremor is an uncontrollable shaking movement that affects a part of the body, often the hand. Tremor will usually begin on one side of the body and then progress to both sides as Parkinson’s progresses. The most typical tremor in Parkinson’s is called a ‘pill-rolling’ rest tremor, as it resembles the action of rolling a pill between the thumb and index finger.

A tremor may be more obvious when a person is resting or when they get worried or excited. Sometimes you will hear it referred to as a ‘resting’ tremor because it usually lessens when a person is carrying out an activity, such as picking up a teacup. A tremor can make some daily activities difficult and can be frustrating. In the video below we can see the impact that symptoms like tremor can have on people with Parkinson’s.

Transcript

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

How a tremor progresses

Parkinson’s tremor usually gets worse over time. However, generally this is quite a slow process that occurs over several years.

‘[My doctor] put me on levodopa…as time went on the medication started to work, but still anxiety and agitation would make the tremors come back’

Typically, Parkinson’s tremor starts in the fingers of one hand before spreading up the arm. The tremor can also spread to affect the foot on the same side of the body. Occasionally, a tremor starts elsewhere, for example, in the foot, and then may spread up the leg and into the arm.

You may notice that some people with Parkinson’s have a tremor on both sides of their body. This is because after several years, the tremor can spread, but this tremor is likely to be milder. In severe cases, the tremor can also spread to involve the jaw, lips, tongue or torso. Some people also experience an ‘internal tremor’. This is a feeling of tremor within the body, but it isn’t noticeable to other people.

What makes a tremor worse?

You may have noticed that some people find their tremor gets worse with anxiety, anger or excitement. However, this is temporary, and the tremor should settle when they have calmed down.

You should be aware that a Parkinson’s tremor can be caused or made worse by some drugs, such as tranquilisers, anti-nausea and anti-dizziness medications. Some anti-asthma drugs, antidepressants and epilepsy drugs could also make a tremor worse. We will look at which drugs these are in Section 4.

Of course, a person may need these medications, in which case they should seek advice from their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

Treating a tremor

Some medications, including levodopa and dopamine agonists, may help to suppress a tremor. Deep brain stimulation, which we will look at in more detail in Section 4, may also help for a small percentage of people.

Because anxiety or stress can make a tremor worse, it’s important that you help people with Parkinson’s to stay relaxed. Complementary therapies may help.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK complementary therapies information.

Actions to take

- Remember that anxiety and stress can make a person’s tremor worse, so try to help people with Parkinson’s stay calm and relaxed.

- If you think a person’s tremor is getting worse, their specialist or Parkinson’s nurse may be able to suggest changes to their drug treatment that will improve this symptom.

- Make sure medication is taken on time.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK tremor information sheet.

2.5 Helping to manage stiff, rigid or frozen muscles

Simple movements, such as getting up from a chair, rolling over in bed, moving fingers to write or fastening a button can be difficult, frustrating and sometimes painful for someone with Parkinson’s. Stiff and painful joints, especially shoulders, are common.

There are two types of rigidity:

- ‘lead pipe’, when both arms and legs are very rigid and held quite tightly to the body

- ‘cog wheel’, characterised by a clicking feeling as the limb is being bent – it feels like a cog wheel moving round.

Transcript

This lady has fluctuating rigidity as part of her symptoms of Parkinson’s. She has been asked to move her arm up to her shoulder and back down to a resting point as part of a series of exercises. At first, you can see that she moves her arm quite freely. She is able to complete the full range and motion of the movement. But the longer the exercise goes on, you can start to see that her movement becomes slower. She is finding it harder to complete the full range and movement of the exercise. And that is due to the rigidity that is starting to impact on her arm movements.

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

It is important to check if the person you are caring for is taking or needs pain relief for these symptoms. If you think they do need pain relief, report this to your manager. Generally the person’s GP or Parkinson’s nurse will be able to prescribe adequate and appropriate medication. If this does not help, they may need to see their specialist.

Further information is available in the Parkinson’s UK information sheet on pain.

People with Parkinson’s can experience problems with facial expression because of difficulty controlling stiff facial muscles. Sometimes people may make expressions that they didn’t plan to make, or they find it difficult to smile or frown. This can make it hard to express how they feel about a situation or something that another person has said. It can also affect people’s confidence in social situations. We automatically read people’s faces and respond appropriately. When you are talking to someone with Parkinson’s remember to be aware that they may be feeling differently from how they look.

Freezing

Some people with Parkinson’s will suddenly freeze when making a movement like walking. Freezing often happens when something interrupts or gets in the way of a sequence of movements. Many people with Parkinson’s describe freezing as times when their feet feel ‘glued to the ground’. They might not be able to move forward again for several seconds or minutes.

Some people may feel like their feet are ‘frozen’ or stuck, but that the top half of their body is still able to move. They might freeze when they start to walk or when they try to turn around. But freezing does not just affect walking – some people freeze during speaking or during a repetitive movement, like writing or brushing their teeth.

Freezing can get worse if a person is worried, in a place they don’t know or if they lose concentration. Not knowing if and when you might freeze can cause anxiety for people and have an impact on what social activities they choose to do. If a person has trouble starting a movement, this is sometimes called ‘start hesitation’. They might freeze when trying to step forward just after standing up, or when they lift a cup to drink, when they start to get out of bed.

‘I can walk so much better on these paving slabs because I can judge my stride. If every floor was made like this I'd be delighted...I don't even have to use my stick.’

Freezing can also happen with thought. Some people find this when they are trying hard to remember something in particular, for example trying to remember names.

Where and when it can happen

People with Parkinson’s are most likely to freeze when they are walking, as walking is a series of individual movements that happen in a particular order. If one part of the sequence is interrupted, the whole movement can come to a stop.

People are also more likely to freeze when walking towards doorways, turning or changing direction, in crowded places, or when their medication isn’t working very well. It’s more likely to happen if a person has had Parkinson’s for some time, and if they have been taking levodopa drugs for a number of years. But freezing can be experienced by people who are not taking levodopa, so it is not just a side effect of medication.

Is freezing the same as going ‘off’?

Freezing is not the same as being ‘on’ or ‘off’ When a person's symptoms are well controlled, this is known as the 'on' period, which means that medication is working well. When symptoms return, this is known as the 'off' period.

There are different ways of managing freezing and ‘on/off’ ‘periods’, so they must be seen as separate problems. During ‘off’ periods, people with Parkinson’s will hardly be able to move at all, so walking, going upstairs or reaching for a cup will be difficult. When people freeze, it only affects certain movements, so they may not be able to walk, but can still reach for a cup. We will revisit ‘on/off’ in Section 4.

Treating freezing

Treatments for freezing may include changes to a person’s medication regime, occupational therapy and physiotherapy. You may be one of these therapists or you may be able to ask for a referral to them. Deep brain stimulation may also help some people.

Techniques to help people experiencing freezing

There are some methods that can ‘cue’ people to trigger them to move again. You may be able to improve someone’s mobility and reduce anxiety by introducing cueing techniques. These are listed in our information sheet Freezing in Parkinson’s.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK freezing information sheet.

Actions to take

Find out if the person has any problems with freezing by observing them or asking them. If they do, report the problem to your manager. They may need changes to their medication or they may benefit from seeing a physiotherapist.

- For some people it is the start of a movement that is hard, such as taking the first step to walk. A physiotherapist can give tips to help with this and advise on ‘cues’.

- These can include counting steps and using trigger words to encourage movement.

- If you notice the person with Parkinson’s you care for is regularly freezing, you can arrange a medication review with their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

- Make sure the person is receiving their medication on time, every time. (You will learn more about the importance of medications management in Section 4.)

- Encourage people to engage in regular physical activity, especially as evidence shows that increasing exercise can help improve symptoms. This can help to strengthen muscles, increase mobility in their joints and build up their general fitness and health.

2.6 Non-motor symptoms

People living with Parkinson’s can experience a range of non-motor symptoms, such as sleep, mood and memory problems, which can often have a greater impact on their lives than movement difficulties. Non-motor symptoms are present at all stages of the condition but they can dominate in the complex phase of Parkinson’s.

These symptoms can be poorly recognised and insufficiently treated. So it is essential that they are recognised as early as possible and that there is a multidisciplinary approach to each person’s care.

There are many non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s, including pain, memory loss, bladder and bowel problems, mood changes, and difficulties sleeping. Here we look at some of the more common examples and what you can do to help those living with them.

2.7 Eating and drinking difficulties

Many people with Parkinson’s have some difficulties with eating and swallowing. The medical term for this is dysphagia.

There are many reasons why people with Parkinson’s may experience difficulties with eating and drinking. Many of these relate to their mobility problems. Chewing can be difficult and Parkinson’s can cause difficulties in the muscles of the tongue.

While eating, frequent swallowing may mean that saliva is used up, causing a dry swallow, which can feel uncomfortable. Also, some Parkinson’s medications can alter the taste in a person’s mouth or cause a dry mouth. A person with Parkinson’s may have swallowing problems if they have any of these symptoms:

- loss of appetite

- weight loss

- drooling

- inability to clear food from the mouth

- food sticking in the throat

- a gurgly voice

- coughing when eating or drinking

- choking on food, liquids or saliva

- problems swallowing medication

- pain when swallowing

- discomfort in the chest or throat

- heartburn or reflux

- repeated chest infections.

These symptoms can impact on people’s health and their enjoyment of food.

What can help?

Speech and language therapists can help with exercises and techniques to overcome some problems with eating and swallowing. Following an assessment, a speech and language therapist will develop a management plan to suit individual needs that might include:

- adjusting a person’s posture and head position when eating or drinking

- using special equipment to help them eat and drink more safely and comfortably

- exercises to strengthen their lip, tongue and throat muscles to make their swallowing more effective

- changing their diet to make foods and liquids easier and safer to swallow – this may include avoiding hard, dry or crumbly foods, or thickening drinks to make them move more slowly in the mouth

- talking to their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse about the timing and doses of medication, as eating meals shortly after taking some medications may improve swallowing

- improving breathing techniques.

‘You have to monitor yourself, take your drugs when you should. I do notice when I have excesses of protein, a t-bone steak or whatever, that my medication is slow to work.’

Sometimes issues with eating and drinking are not to do with the physical aspects of swallowing, but more to do with the practicalities of eating and drinking. Occupational therapists can provide advice and equipment, and dietitians can advise on suitable foods.

In a care or hospital environment, food may often be taken from a person with Parkinson’s because the professional assumes that they don’t want it. This may be because the person is taking a long time to eat or because the food has gone cold and looks unappetising.

People with Parkinson’s may need a lot of time to enjoy eating on their own or they may need your help at every meal.

Actions to take

- Report any problems. Your client may benefit from seeing a speech and language therapist, occupational therapist or dietitian.

- Look at how well they can use and coordinate their hands.

- If they want to eat on their own, allow them lots of time as they may be slow.

- Make sure they drink enough fluids.

- Your client might find specially designed cutlery or cups useful – an occupational therapist can advise on the best ones to use.

- Check if the person has problems with chewing and swallowing, which could cause choking or breathing problems.

- If it takes a long time for someone to eat, you could give them half of the meal and keep the other half warm until they are ready to eat it.

- Some people may lose weight as a result of eating difficulties. The dietitian can offer advice about getting a good diet and about the types of food that may be easier to swallow. They may also recommend nutritional supplements.

2.8 Swallowing and saliva problems

Many people with Parkinson’s have trouble swallowing at some point during the course of their condition. Drooling is one of the first signs of a swallowing problem. This will happen because the person can’t close their lips properly, finds it hard to swallow regularly or aren’t sitting in a good position. This can cause saliva to collect in the mouth, which can cause overspill and drooling. This can be embarrassing and lead people to avoid social situations.

There are four main problems that are linked to swallowing:

- a chest infection caused by food or liquid from the mouth going into the lungs rather than the stomach (known as ‘aspiration pneumonia’)

- not eating enough to maintain good general health (malnutrition)

- not drinking enough, which can lead to constipation or dehydration

- food blocking the airway and stopping a person’s breathing (asphyxiation).

Because of this it is very important to seek medical advice if someone has problems with swallowing.

Some problems with swallowing may not always be obvious to you or the person with Parkinson’s. If the food we swallow enters our windpipe instead of our food pipe, our bodies react by coughing to stop food entering the lungs. In some cases, people with Parkinson’s can have what’s called ‘silent aspiration’. This is when food enters the windpipe and goes down into the lungs without any of the usual signs of coughing or choking. This can lead to problems such as aspiration pneumonia.

As well as the social anxieties caused by problems with eating, some people may also be afraid of choking. Swallowing difficulties may also make it harder for people to take their medication. Providing iced water with medication or meals may help with swallowing.

A person with Parkinson’s may also show signs of a swallowing problem if they:

- can’t clear food from their mouth, or if food sticks in their throat

- have pain or discomfort in their chest or throat

- have an unclear voice

- cough or choke on food, drink or saliva

- experience weight loss

- have trouble swallowing their medication

- have heartburn, acid reflux or lots of chest infections.

Actions to take

- Report any problems. Your client may benefit from seeing the speech and language therapist or dietitian.

- A speech and language therapist can help your client with exercises to strengthen the lip, tongue and throat muscles. They can also advise on ways to improve breathing techniques.

- A dietitian can advise your client on changes to their diet so that foods and liquids are easier and safer to swallow. For example, avoiding hard, dry or crumbly foods. Liquids may be thickened with powdered thickeners, milk powder, instant potato powder or plain yoghurt, as thicker liquids move more slowly and are easier to control.

- Make sure that medication is taken on time so that the person can swallow well at mealtimes. Changes to a person’s medication regime may also help and there are drugs that may control saliva production. A doctor may inject Botox (botulinum toxin) into the salivary glands to quickly reduce saliva.

- Try making changes to the person’s posture when they’re eating or drinking – having their head tilted forwards will make it harder for food to go to the lungs.

- If the person’s dentures are loose and uncomfortable, they’ll need to see the dentist.

For some people, these solutions will not be enough and a different feeding method might be needed. Some people with Parkinson’s may also experience problems with a dry mouth. Specialist dry mouth products, such as artificial saliva, are available. Their Parkinson’s nurse will be able to provide advice.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK eating swallowing and saliva control information sheet.

2.9 Sleep problems and tiredness

Sleep and night-time problems are common in Parkinson’s and can be a side effect of medication. But keep in mind that these problems may have other causes than a person’s condition. For example, difficulty sleeping can be linked to other things, including drinking too much caffeine.

Not getting enough sleep can cause problems similar to the symptoms of depression – some people may feel confused or irritated. Lack of sleep also makes it more likely that the person will experience hallucinations or delusions. Parkinson’s symptoms might get worse when a person is tired.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK hallucinations and delusions information sheet.

Insomnia

Symptoms of insomnia are common in most long-term conditions. People with Parkinson’s can be more prone to insomnia because of Parkinson’s symptoms, such as restless legs syndrome, that can disturb sleep.

Side effects of medications such as selegiline can act as stimulants and keep people awake.

Treating insomnia

If you work with someone who suffers from insomnia there are treatments that can help them to manage and deal with this problem. Their GP may also be able to refer the person to a psychological practitioner.

Psychological treatments for insomnia look at making helpful changes to habits and feelings that may affect our sleep. Some examples of simple night-time routine changes that can help your clients include:

- following the rules of good ‘sleep hygiene’ (for example, avoiding drinks containing caffeine or alcohol four to six hours before bedtime and keeping the bedroom calm, comfortable and cool)

- spending less time in bed awake

- going to bed only when you feel sleepy

- going to bed and getting up at regular times

- avoiding worrying in bed.

Some causes of disturbed sleep are related to Parkinson’s itself or to the medication used to treat it.

Not getting enough sleep can have a big impact on someone’s day – think about a time when you didn’t get enough sleep and the impact that had.

Parkinson’s medication

Common Parkinson’s symptoms can get worse as the effects of medication start to wear off. These symptoms may include stiffness, tremor, pain and being unable to move and turn in bed (nocturnal akinesia). An increase or worsening of these symptoms could affect the ability of a person with Parkinson’s to sleep well.

If this happens, a person should speak to their specialist or Parkinson’s nurse about making changes to their medication. Some medications can provide constant treatment through the night.

Turning over in bed (nocturnal akinesia)

Turning over in bed can be difficult for people with Parkinson’s because of rigidity. If a person with Parkinson’s finds it hard to turn over in bed, they may need changes to their medication. They should also have a night-time care plan in place and, if appropriate to your role, you should check if they need any care for pressure ulcers. An occupational therapist may also be able to suggest aids to help people to turn over in bed, such as a bed lever.

Akinetic pain

Symptoms of akinetic pain include severe stiffness, fever, pain in muscles and joints, headache, and, sometimes, pain in the whole body.

Early morning dystonia

Dystonia is an involuntary muscle contraction (for example, in the toes, fingers, ankles or wrists) that causes the body to go into spasm. This often occurs in the early morning as the effects of Parkinson’s medication wear off.

Restless legs syndrome

‘Jumping’ of the legs, arms or body during sleep is not uncommon in Parkinson’s. The effect is known as ‘periodic leg (or limb) movements’. Some people get it with restless legs syndrome, but it can happen on its own.

Restless legs syndrome is an irresistible desire to move the legs when a person is awake. People with Parkinson’s may get this during the evening and at night. Restless legs can cause discomfort at night for people with Parkinson’s, which can impact on sleep. It is common in people with Parkinson’s, although other conditions such as diabetes may also cause this problem.

Similar symptoms to restless legs syndrome can be caused by some Parkinson’s drugs or by drugs ‘wearing off’.

If you think a person is experiencing any problems with pain or restless legs, their medication regime may need to be adjusted. Their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse should be able to help.

Nocturia

Waking up at night with the urge to urinate can be a common problem for people with Parkinson’s, although there may be other causes, such as a bladder infection. The GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse can work out the cause of nocturia and suggest ways to manage or treat it. A continence advisor can also help.

Low blood pressure or hypotension

You may notice that some people with Parkinson’s can feel light-headed and giddy if they try to stand up quickly (for example, when getting out of bed). A health professional can provide advice.

Panic attacks, anxiety and depression

Feelings of excessive worry or stress can cause sleepless nights. These symptoms can affect people with Parkinson’s. They are treatable and there are a number of ways this may be done. A health professional can provide advice.

Parasomnias

Parasomnias are abnormal movements or behaviours that happen when a person is sleeping, when they are waking up or when light sleep changes to deep sleep. They include nightmares and sleepwalking.

Some people with Parkinson’s may also experience hallucinations, wandering, agitation or may talk loudly during sleep. Night-time hallucinations can be a side effect of medication taken at night, or may be caused by something else, such as infections.

If a person experiences parasomnias, their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse should be notified. In some cases a neurologist with a special interest in sleep disorders may be consulted.

Excessive daytime sleepiness

Drowsiness - in some cases, severe drowsiness - is a side effect of some Parkinson’s drugs. All Parkinson’s medications can cause excessive daytime sleepiness or sudden onset of sleep. This may be more likely to affect people with later stage Parkinson’s on multiple medications and when increasing medication, particularly dopamine agonists. (Dopamine agonists are a type of Parkinson’s drug. We will look at what they are in in detail in Section 4.)

People may also feel excessively sleepy during the day if they are not getting enough sleep at night. This can cause people to fall asleep or doze off during normal waking hours. In some cases, it can even lead to the sudden onset of sleep. If you see that this is a problem for your client, medication may help – you can seek the advice of a health professional.

Sleep apnoea

Sleep apnoea is a condition where a person momentarily stops breathing while asleep. This makes them wake up, take a few breaths and go back to sleep again. The person has no memory of this happening, because it’s so brief, but it disturbs their sleep.

Symptoms of possible sleep apnoea include loud snoring, choking noises while asleep or excessive daytime sleepiness. Seek advice from a health professional.

Sleep medication

If your client is having long-term problems sleeping, they may be taking or considering sleep medication, such as sleeping tablets. Their GP should be able to advise them about sleep medication.

Find out more from the Parkinson’s UK sleep and night time problems information.

Actions to take

- Recommend your client keeps a sleep chart. This can be taken to their next appointment with their specialist to assess their difficulties.

- Where appropriate, recommend keeping a call bell within their reach, so that they know help is at hand at night when it’s harder to move.

- They will need reassurance if they are experiencing nightmares. These can be very distressing.

- Make sure people have adequate pain relief.

2.10 Bladder and bowel problems

Incontinence (where someone can’t control their bladder or bowel) and constipation (where someone has trouble passing stools) are common for people with Parkinson’s. They can be caused either by the condition or by Parkinson’s medications.

Many people with Parkinson’s experience bladder and bowel problems. However, it is important to remember that some of these problems can be common in men and women of all ages, whether they have Parkinson’s or not. So it doesn’t necessarily mean that any problems a person with Parkinson’s has are a result of their condition. There may be other causes for their symptoms that can be treated effectively.

Constipation is a common symptom of Parkinson’s and unfortunately some Parkinson’s medication can make this worse. It is important that people with Parkinson’s do not become constipated as this can result in poor absorption of their medication and therefore poor symptom control.

Bladder and bowel problems can impact on people’s lives, causing discomfort and embarrassment.

Bladder problems

The two main bladder problems associated with Parkinson’s are urge incontinence (the need to urinate immediately, without warning) and nocturia (an overactive bladder that causes people to wake in the night). The bladder may also empty when someone is asleep. A common bladder problem in the general population is stress incontinence.

For women, childbirth can stretch pelvic floor muscles, causing incontinence. Falling hormone levels caused by the menopause may also mean the watertight seal is less effective. For men, prostate problems may cause difficulty emptying the bladder, the need to urinate more often, urgency or retention.

Treating bladder problems

Depending on the problem, medication, bladder training, pelvic floor exercises, catheterisation or surgery may help with bladder problems.

Often people cut down on the amount of fluid they drink when they experience bladder problems. They should be encouraged to drink as much fluid as usual, although they may find it helpful to cut out caffeine, fizzy drinks and alcohol. Reducing fluids could cause constipation, which could reduce the absorption of medication.

There are also many different products that can help, including handheld urinals, pads, underwear and bed protection.

Bowel problems

People with Parkinson’s may experience constipation, diarrhoea or a weak sphincter. Some people with the condition may soil their underwear because they are unable to wipe effectively.

Any change in bowel habit, particularly if there is blood in the stool, should be reported to a person’s GP. Constipation should be treated to avoid impaction – when the bowel is loaded with hard stools and so begins to overflow. Impaction can cause a complete obstruction to the bowel, needing urgent medical attention.

‘Incontinence pads…Not a very nice subject to talk about, but it’s got me out of trouble a few times. It took me a whole year to decide to wear these. Sometimes you just have to give in and be sensible.’

Treating bowel problems

You can help people avoid becoming constipated by increasing their fluid intake, encouraging them to take exercise and increasing their intake of fibre-rich foods. Laxatives may also help.

How does fibre help?

Fibre works by absorbing fluid as it moves through the bowel, forming a soft stool that can be passed more easily. But too much bulk can increase constipation, especially if the person does not drink enough.

Make sure your client drinks at least eight to ten cups (or six to ten mugs) of fluid a day. Any fluid is suitable, including water, fruit juice, milk, tea, coffee and squash.

People with Parkinson’s can increase their fibre intake by doing the following:

- Choosing a breakfast cereal containing wheat, wheat bran or oats such as Weetabix, porridge or bran flakes.

- Eating more vegetables, especially peas, beans and lentils.

- Eating more fruit – fresh, stewed, tinned or dried – such as prunes or oranges.

- If your patient has difficulty with chewing high-fibre food, there are soluble varieties available and even some high-fibre drinks.

- Loose, extra bran that can be added to food is not recommended by dietitians. This can lead to bloating and can reduce the absorption of vitamins and minerals by the body.

When increasing a person’s fibre intake, it is important to do so gradually to avoid bloating or flatulence (wind). Introduce one new source of fibre every three days.

Remember that some people with Parkinson’s may have problems chewing and swallowing, which can make it difficult to eat a diet with plenty of fibre. A dietitian or speech and language therapist can give advice about this.

Practical problems

Keep in mind that bladder and bowel problems can be made worse by practical issues. For example, some people may find it hard to undo clothing such as zips. Others may find it difficult to position themselves on the toilet correctly. The occupational therapist can provide advice about any necessary adaptations.

Professional help

Professional help may come from the GP, urologist, gynaecologist, the district nurse or the continence advisor, among others.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK bladder and bowels booklet.

Actions to take

- If the person with Parkinson’s has movement problems, you may (where appropriate) need to help them to visit the toilet.

- Someone with Parkinson’s might need to urinate often and may need to visit the toilet without much warning.

- Allow plenty of time so they feel comfortable and are unhurried.

- Consider aids such as commodes or urinals.

- Keep or recommend keeping a fluid, diet and stool chart. These can be taken to the person’s next appointment with their specialist to assess their difficulties.

2.11 Falls

Problems with balance and posture are common in Parkinson’s and the problem tends to increase over time. A person with Parkinson’s may walk very slowly, take small, unsteady steps and stoop forward, which makes them more likely to fall.

People may be anxious about falling when they are outside of their normal environment. Repeated or bad falls can impact on people’s health and mobility.

The following are all possible reasons people with Parkinson’s might fall.

- Physical reasons for falling: Freezing can cause some people to fall. As Parkinson’s progresses, a person’s posture can change – it may become more stooped and muscles can become more rigid. This inflexibility can also increase the risk of falling.

- General weakness: People with Parkinson’s can be much less active than they used to be, which can cause muscles to become weaker. This weakness can be a major cause of falls – so it is important to stay as active as possible to stop muscles and joints getting stiff and rigid.

- Postural hypotension: Low blood pressure can make some people with Parkinson’s dizzy when they stand up, so they’re more likely to fall over.

- Parkinson’s medication: Blood pressure problems can be a side effect of most kinds of Parkinson’s medication, which can cause dizziness. This may lead to falls. Your client may be taking drugs used to treat other medical conditions, such as high blood pressure, which can potentially make this dizziness worse. If this happens, their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse should be informed. You can also help people avoid dizzy spells by making sure they are taking their medication as prescribed. If their drugs don’t seem to be working as well as they used to, a person might need their medication to be reviewed.

Hazards in and around the home/residential care home

Many things in the place where someone lives could be hazardous and make people more likely to fall, including slippery floors, loose carpets and general clutter. Here are some tips on how to reduce hazards in the home:

- Try to clear away as much clutter as you can and arrange the furniture so that moving around is as easy as possible.

- Hand or grab rails may be useful in tight spaces, such as in toilets, bathrooms or by the stairs. Putting non-slip mats in the bathroom will also help.

- Always make sure a person’s environment is well lit.

- If possible, apply strips of coloured tape to the edge of steps to reduce slipping and to make them more visible.

- Make sure they have commonly used items close to hand.

- Floor coverings can sometimes be a hazard. For example, carpet patterns can be visually confusing. Speak to the occupational therapist or physiotherapist about applying strips of tape or plastic footsteps on the carpet. These can guide people in places they may be more likely to fall, such as a tricky turn on stairs, or in doorways.

General advice

It’s important to encourage people to try to stay as active as possible and to exercise regularly to maintain their mobility and prevent falls. Walking aids and supportive footwear may also be helpful.

It’s important to seek advice from the physiotherapist or occupational therapist before using aids. This will help to make sure that people are using the most appropriate support.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK information sheet on falls.

Actions to take

- Where appropriate, report any falls.

- Your client may benefit from physiotherapy, so a referral may be necessary.

2.12 Pain

For some people, pain can be the main symptom of their condition, although not everyone will experience this problem. Uncontrollable muscle contractions (dystonia) and rigidity can be a problem in Parkinson’s. This is very painful, like bad cramp, and hurts most when Parkinson’s drugs are ‘wearing off’ or when someone is taking their medication less frequently.

The most effective way to treat pain in Parkinson’s is to find the cause of the pain. It is best for the person with Parkinson’s to speak to their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse. Usually, the GP will be able to manage the more common types of pain, such as musculoskeletal shoulder pains and headaches. However, other types of pain, such as dyskinetic pain or a burning mouth, may need a referral to a specialist. The main types of pain associated with Parkinson’s are discussed below.

Muscle (musculoskeletal) pain

This is the most common type of pain experienced by people with Parkinson’s. It comes from the muscles and bones, and is usually felt as an ache around joints, arms or legs. The pain stays in one area and doesn’t move around the body, or shoot down the limbs.

Simple painkillers, such as anti-inflammatory medications, and exercise can help.

Muscle cramps

Muscle cramps associated with Parkinson’s can happen at night or during the day. At night they may cause pain in the legs and calf muscles as well as restlessness, which leads to disrupted sleep.

Cramps can be soothed by stretching and massaging the affected muscle.

Dystonia

Dystonia is an involuntary muscle contraction that can make the affected part of the body go into spasm.

In Parkinson’s this is most common on feet, legs, head and neck. Dystonia can cause the feet to turn inwards, or toes to curl downwards.

Medication can help – if dystonia is a problem then anyone who has it should see their specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK information on muscle cramps and dystonia.

Radicular pain

This is a sharp, often shock-like shooting pain that travels down the leg or arm and may involve fingers and toes. Tingling and numbness, or a burning feeling in the toes and/or fingers is also common in people with Parkinson’s.

Radicular pain is usually the result of a trapped nerve within the spinal cord around the neck or lower back region.

Simple painkillers and gentle exercise may help. They may need some tests, such as an MRI scan of the spine, to rule out compression of the nerve roots at the spinal cord.

Dyskinetic pain

This sort of pain is not limited to any body part and can be described as a deep, aching sensation. It can occur because of involuntary movements (dyskinesia) that some people with Parkinson’s experience. It can happen before, during or after movement.

Adjusting Parkinson’s medication can help. If dyskinesia is a problem, anyone with it should see their specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

Restless legs syndrome

This can cause symptoms such as pins and needles, painful sensations, or a feeling of burning in the legs. Some people may feel an irresistible urge to move their legs while relaxing, such as while sitting watching TV or getting to sleep. Medication can help.

Other types of pain associated with Parkinson’s

There are other types of pain associated with Parkinson’s that are less common. These can include shoulder or limb pain, pain in the mouth and jaw, and headaches.

‘I also experience muscle stiffness and inflexibility, which cause me pain due to over-exertion. This happens if I don't take regular breaks throughout the day’

Some people may also experience akinetic crisis and pain, which usually only occurs in the advanced stages of Parkinson’s. The symptoms include severe stiffness, fever, pain in muscles and joints, headache and, sometimes, whole-body pain.

Some people occasionally experience this type of pain if their Parkinson’s symptoms suddenly get worse. This can be brought about by abrupt withdrawal of Parkinson’s medication or by infections. Severe stiffness in the muscles may also be the cause.

If you think your client is experiencing pain, always recommend they seek advice from their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

Actions to take

- People with Parkinson’s might take pain relief as part of their drugs regime. If they’re not happy with what they take, or if pain relief needs to be added to their regime, they may need a review of their medication with their specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK information sheet on pain.

2.13 Care planning

A person’s Parkinson’s symptoms and how these symptoms affect them can change (fluctuate) from day to day, and even from hour to hour. This can be caused by Parkinson’s or the medication used to treat it. Because of this, it’s hard to assess the needs of someone with the condition. Symptoms will get worse when someone’s Parkinson’s drugs are wearing off and improve again after Parkinson’s drugs are taken.

Actions to take

- Speak to the person and their carer (if they have one) about their individual needs. They know best how the condition affects them.

- When doing a care needs assessment, make sure you meet with the person on several occasions and at different times of the day. They should be reviewed regularly.

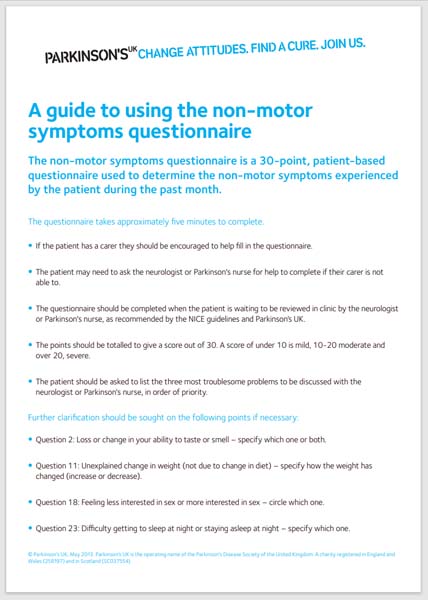

- Use the non-motor symptoms questionnaire below to help you get a clear picture of how Parkinson’s is affecting the individual. Remember that everyone experiences the condition in a different way.

Non-motor symptoms questionnaire

By looking through this questionnaire you’ll begin to get a sense of the non-motor symptoms that can affect people with Parkinson’s.

This questionnaire can be used by people with Parkinson’s to help them explain to a healthcare professional how their non-motor symptoms are affecting them. This can help healthcare professionals to treat the person with Parkinson’s appropriately.

Health or care workers can help people affected by Parkinson’s and their family to fill in the non-motor symptoms questionnaire before they visit a doctor or Parkinson’s nurse.

Often people with Parkinson’s don’t realise these symptoms are part of their condition and they can go unreported.

There are many more non-motor symptoms experienced by people with Parkinson’s than we have time to explain in this course. Please study the non-motor symptom questionnaire to familiarise yourself with these.

You can download the non-motor symptoms questionnaire on the Parkinson’s UK website.

2.14 What is the impact of Parkinson’s on people’s daily life?

So far we have separated the symptoms from the person. We will now look at a case study that allows you to reflect on what these symptoms can mean for people on a daily basis.

Exercise 2.2

Please watch the following video of Andrew and Ruth, who talk about Andrew living with Parkinson’s. While you are listening, write down the areas of Andrew’s life that you think are affected by Parkinson’s. You may also consider other people who may be affected by the condition. Use the reflection log to record your thoughts. You may want to write by hand as you listen and then record in the log afterwards.

Transcript

Caption: ‘Getting out of bed’

Caption: ‘Eating and salivation’

Caption: ‘Planning for the future’

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

Discussion

When you were completing your reflection log you may have realised that Andrew is currently in the complex phase of Parkinson’s. He will become increasingly dependent on his wife and be concerned about the impact his condition has on her.

Areas of Andrew’s life that are currently affected are:

- Poor mobility

- Fluctuation of symptoms

- Severe pain and rigidity

- Difficulties eating and swallowing

- Difficulty playing the guitar

- Slowness of movement

- Loss of sense of taste

- Nocturia

Use the reflection log to answer the following questions:

- Which area/activity of daily life described in the video do you think has the biggest impact on Andrew’s quality of life?

- How do you think the changes to Andrew’s daily life could impact on Ruth?

- If this was your life, what might your overriding emotion be?

Discussion

People with Parkinson’s can often be labelled as difficult, angry, frustrating, etc. But it’s vital that those caring for people with the condition should treat people with Parkinson’s with empathy and understanding.

Does hearing about Andrew’s life with Parkinson’s help you to understand a little better why people with the condition may feel frustrated, and upset at times? Have you ever seen those emotions in a person with Parkinson’s that you have worked with?

Everyone will have different answers for each of these questions and there are no right or wrong answers.

You may have said that the impact on Ruth of changes in Andrew’s daily life could be one or more of the following: Frustration at not being able to go on holiday, sadness or depression at seeing Andrew in pain and not able to play his guitar as well as he once could, tiredness due to interrupted sleep when Andrew gets out of bed to go to the toilet, frustration communicating with Andrew due to his slowness, exhaustion at having to clean up more often after Andrew spilling or choking on his food, and social isolation.

You may have said that your overriding emotion would be frustration, exhaustion, anger, sadness and depression.

This exercise demonstrates how difficult living with Parkinson’s can be. Each person living with the condition will have their own personal set of circumstances that will contribute to how they experience Parkinson’s. These circumstances will include what symptoms they have, their age, financial status, family life and medication regime, to name just a few.

Everyone experiences Parkinson’s in their own way and will have their own outlook on life with the condition. People with Parkinson’s should not be defined by the fact that they have the condition. It is important to remember that they have led varied and interesting lives before and after the development of the condition.

Discussion

However, it is vital to take into account that, when they reach the complex phase of the condition, some people with Parkinson’s will be (or have been) forced to give up many of the activities that they have enjoyed for a long time. By this stage they will probably be struggling with basic activities, such as maintaining personal hygiene or getting out of bed. This is why care staff will be providing support at this time in their lives.

2.15 The impact of Parkinson’s on a family

Exercise 2.3

You have considered the impact of Parkinson’s on Andrew and Ruth's life. In Section 1, we also considered the emotional, social and psychological impact of Parkinson’s on Daxa. We will now consider how you might feel if you were affected by Parkinson’s.

Look at the list of everyday activities below. Many of these are activities that make our lives rich and interesting, and give us things to talk about and look forward to.

| Wash | Talk | Go to the toilet |

| Walk | Have sex | Eat |

| Dress | Clean your teeth | Cook |

| Climb the stairs | Play sport/exercise | Socialise |

| Household chores | Write | Work |

| Hobbies | Gardening | Get out of bed |

| Get out of a chair | Answer the phone | Dance |

| Turn over in bed | Shop |

The extent to which people with Parkinson’s are able to carry out these activities will vary. But people in the complex stage of Parkinson’s will probably be struggling with the really basic activities, such as brushing their teeth or washing themselves. This is why you will be providing vital support at this time in their lives.

Keep the previous case studies in mind when you look at the next exercise.

Use the reflection log to answer the following questions. How might you feel if you:

- Were unable to drive anymore?

- Were unable to take part in a much-loved hobby, like gardening or knitting?

- Could no longer go to the pub or into town for a coffee?

- Lived with Parkinson’s, and these were the consequences?

It is important to realise what people with Parkinson’s in the complex stages of the condition are going through and how their symptoms may affect them. They are not being difficult or stubborn. A person’s Parkinson’s symptoms can fluctuate. This means that what they are capable of can also change from day to day, or even hour to hour. Consider how understanding this may influence your practice.

2.16 Parkinson’s: a personal account

We will now look at the experiences of another person with Parkinson’s – Keith Emery. Read Keith’s personal account of living with Parkinson’s and consider the changes to his daily activities. Use your reflection log to write down what those changes are and how you may change your practice following these activities.

Case Study 2.1 Keith Emery’s story

Keith Emery’s story

Keith was diagnosed with Parkinson’s ten years ago. Here, he explains what Parkinson’s is like for him, and what he’d like others to understand about it.

I put my muscle pain down to work first of all… my GP was pretty sure it was Parkinson’s…a neurologist…sent me for a datscan…and on the 26 Sept 2019 he confirmed it was Parkinson’s.

I had tremors, I lost the swing in my left arm. I had a foggy memory sometimes…As time went on the shakes did get worse, and the more I tried to stop them, the worse they got…Dr Knock put me on levodopa…

I started suffering from depression and I stopped socialising…at all with anyone – for two years…always feeling I was being stared at…I used to go for walks at night because I didn’t want to be seen during the day – because my balance was off…I lost my job…Since then I have been on disability living allowance…I didn’t have the money to do anything so I never really went anywhere…My family couldn’t get their head around me having Parkinson’s and didn’t understand the non-motor symptoms: the changes to my personality and behaviour.

I am getting support from all the friends I made at the [Sports Parkinson’s] Parkinson’s event…I was still embarrassed about my condition, but then when I got there I was welcomed, and greeted by people I didn’t know. I had never spoken to or seen them before and it made me feel less uncomfortable…I had fun, something I thought would be alien for me because of my Parkinson’s and the reactions I’d had previously from people I knew. I had other friends, but one by one they were no longer there. Until there was none…After the event, that day changed everything. Everything I felt before meant nothing. It was like sod ‘em, if they want to look then look. I was not going to hide it anymore.

Afterwards I took up dancing. That was to help give me a bit of control over my balance and over my legs. If I concentrated on my dancing my balance improved. I also went along to a martial arts class, to learn how to focus…Since then I have accepted that I have Parkinson’s but I push my limits every day. I am doing things that I wouldn’t normally do – going places, getting out and trying to be normal.

I now have to deal with freezing…I can be out walking and I will become a human statue. I just stand and I laugh. I make fun out of Parkinson’s. I accept that Parkinson’s has a hold on me, but my determination isn’t going to let it control me.

I wake up in the morning and my left side doesn’t move. I find it very hard to move first thing. But I always have my medication by my bed and within 30 minutes of taking it my left hand starts to come to life again and I can do things…If I go places and if I get the shakes and people see it I don’t pay any attention. It feels good. I have made so many friends it is unbelievable.

I had an addiction for making solar panels – once that was done I started getting into collecting watches and travelling across the UK…You learn to fight the additions.

You become more confident because other people tell you their situations and what they have been through, to combat their problems – once you start having fun, that is another good medicine – fun and laughter, understanding there are limitations.

2.17 Summary

We have now looked in detail at the motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s. We have also looked at the impact that these symptoms can have on daily life and how you can support the management of them. Hopefully you have considered how this information can help you improve your practice and increase, where appropriate, the involvement of other health and social care professionals in the care of your client.

Now try the Section 2 quiz.

This is the second of the four section quizzes. As in Section 1 you will need to try all the questions and complete the quiz if you wish to gain a digital badge. Working through the quiz is a valuable way of reinforcing what you’ve learned in this section. As you try the questions you will probably want to look back and review parts of the text and the activities that you’ve undertaken and recorded in your reflection log.

Personal reflection

At the end of each section take time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and what that means for your practice. The following questions may help your reflection process.

Use your reflection log to answer the following questions:

- What did I find helpful about the section? Why?

- What did I find unhelpful or difficult? Why?

- What are the three main learning points for me from Section 2?

- How will these help me in my practice?

- What changes will I make to my practice from my learning in Section 2?

- What further reading or research do I want to do before the next section?

If you have the opportunity to be part of a study group you may want to share some of your reflections with your colleagues.

Now that you’ve completed this section of the course, please move on to Section 3.

Glossary

- bradyphrenia

- Slowness of thought.

- cues

- A way to help someone complete a task by offering prompts.

- deep brain stimulation

- A form of surgery that is used to treat some of the symptoms of Parkinson's.

- delusions

- When a person has thoughts and beliefs that aren’t based on reality.

- dyskinesia

- Involuntary movements, often a side effect of taking Parkinson’s medication for a long period of time.

- dysphagia

- Swallowing difficulties.

- dystonia

- A sustained, involuntary muscle contraction that can affect different parts of the body.

- freezing

- A symptom of Parkinson’s where someone will stop suddenly while walking or when starting a movement.

- hallucinations

- When a person sees, hears, feels, smells or even tastes something that doesn’t exist.

- hypotension

- Low blood pressure.

- impaction

- When the bowel is loaded with hard stools causing obstruction and overflow. Caused by constipation.

- levodopa

- The most effective drug treatment for Parkinson’s. A drug replaces dopamine, the chemical that is lost, causing the development of Parkinson’s.

- motor symptoms

- Symptoms that interrupt the ability to complete learned sequences of movements.

- multidisciplinary

- A group of healthcare professionals with different areas of expertise who can unite and treat complex medical conditions. Essential for people with Parkinson’s.

- nocturnal akinesia

- When a person is unable to turn in bed because of movement problems caused by Parkinson’s.

- non-motor symptoms

- Symptoms associated with Parkinson’s that aren’t associated with movement difficulties.

- ‘on/off’

- If a person's symptoms are well controlled, this is known as the 'on' period, which means that medication is working well. When symptoms return, this is known as the 'off' period. 'Off' periods usually come on gradually, but occasionally can be more sudden. When they come on suddenly, some people have compared this 'on/off' effect to that of a light switch being turned on and off.

- parkinsonism

- An umbrella term that describes conditions which share some of the symptoms of Parkinson's (slowness of movement, stiffness and tremor).

- shuffling gait

- When a person doesn’t have a smooth walking motion when they are trying to walk.

- silent aspiration

- When food enters the windpipe and goes into the lungs without a person coughing or choking. Caused by difficulties swallowing.

- wearing off

- This is where a Parkinson’s drug becomes less effective before it is time for a person’s next dose. This may cause you to go ‘off’.