Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 1:22 PM

Session 2: Understanding adolescence

Introduction

Welcome to the second session of Introduction to adolescent mental health, in which you will learn about the stage of development known as adolescence. You will also have the opportunity to draw upon many of the insights you gained in Session 1 about mental health and its complexities. To get started, watch a short video in which two young women – Martha and Josie – talk about what it was like to be an adolescent.

Transcript: Video 1: Reflecting on adolescence

In this second session, you will learn how ‘adolescence’ is defined and why it is a time of development in a person’s life that brings its own set of challenges. You’ll gain some understanding of young people’s experiences, as well as what is going on in their brains at the same time. It isn’t always clear what is ‘normal’ when it comes to adolescent behaviour and mental health, indeed the very idea of what is normal can be questioned. This session will conclude by trying to shed some light on the idea of normality as it applies to adolescence.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this session, you should be able to:

describe important aspects of development during adolescence

explain how changes in the adolescent brain make adolescence a unique period of development

outline the range of social challenges to mental health that may be experienced during adolescence

discuss the idea of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ adolescent behaviour.

1 Introducing adolescence

Often associated with the teenage years, adolescence is a transitional stage of development, both physically and emotionally.

Marked as a period of development from being a child to becoming a young adult, adolescence is described by many theorists as a time of ‘storm and stress’, often associated with particular behaviours, such as moodiness and irritability. But are these accurate depictions of adolescence? The first activity will help you to consider your own thoughts about adolescent characteristics.

Activity 1: Storm and stress

a.

Moodiness

b.

Impulsiveness

c.

Risky behaviour

d.

Sensitive to peer pressure

e.

Argumentative

f.

Loneliness

g.

Staying up late

h.

Embarrassment

i.

Thrill seeking

j.

Boredom

k.

Importance of friendships

l.

Enjoying sport participation

The correct answers are a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k and l.

Discussion

You probably found it hard to choose just four, but you may have found it helpful to base your choices on someone you know, or even your teenage self. Everything on the list can be attributed to adolescents generally, although not every adolescent would necessarily experience all these things. You can probably think of some adults who fit these descriptions too. People commonly assume that adolescence is a particularly difficult emotional time, and even a time of crisis.

The idea that adolescence is a time of crisis (or ‘storm and stress’) goes back to Psychologist G. Stanley Hall (1904) who described it in very unflattering terms, claiming that, ‘[the period of adolescence] is strewn with wreckage of body, mind, and morals. There is not only arrest, but perversion, at every stage, and hoodlumism, juvenile crime, and secret vice’ (Hall, 1904, p. xiv). Hall believed that young people were in the grip of powerful biological changes that they could not control.

Although he acknowledged that adolescence could be a time of creativity, and crucial to the later development of personality, he also saw it as a time of instability, extremes and contradictions. For example, he saw that young people:

- wished for solitude and seclusion, but also longed to become embedded in friendships and romantic relationships, which took on an overwhelming importance in their lives

- were liable to be full of energy and creativity, but also to descend into gloom and despair

- were capable of idealism and sensitivity, and yet could be extremely cruel and callous

- yearned for idols and for people to look up to and yet rejected ideas of authority and the status quo.

Attitudes have changed since Hall’s time. Adolescence is not necessarily a time of storm and stress. Along with the term ‘crisis’, these troublesome-sounding concepts may be unhelpful because they perpetuate the idea that adolescence is a problem. Many adolescents do not experience conflicts or crises, and move easily from childhood to adulthood. Nevertheless, Hall’s theories of the characteristics of young people have remained highly influential and have coloured subsequent research.

1.1 A time of rapid change

When does a child become an adolescent, and when does adolescence end? These may sound like simple questions, but the answers are not simple. Here are a few definitions of the timing of adolescence. Click on each box to see the explanation. There is a long description button below the figure if this is easier to learn from.

There are many ways of viewing adolescence, and at its core it represents a time of rapid development initiated by hormonal changes. Next, you consider some of the detail.

1.2 Body changes

In adolescence, young people are going through significant physical changes brought on by puberty. They are growing taller, developing secondary sexual characteristics, and their bodies may well be changing in ways that they cannot recognise or that they actively dislike. They are becoming sexual, responding to members of the opposite sex in different ways, or becoming attracted to members of their own sex. The body is a primary site of identity and clearly these physical changes will have a great impact on who they are, on whether they see themselves as a child, on whether they understand themselves as sexual or sexually attractive, and on how they behave with this knowledge.

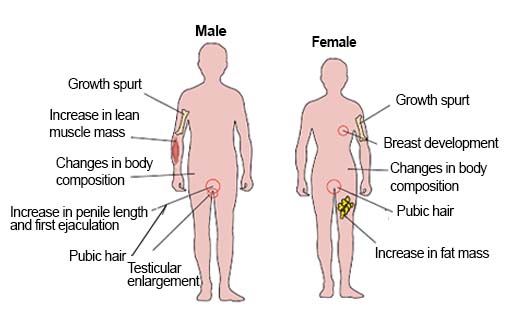

In girls, changes include breast development, menstrual periods, widening hips and growth of pubic hair. In boys, the testicles, scrotum and penis enlarge, facial and pubic hair grows, their voices deepen and they experience ‘wet dreams’ (Wiley and Corey, 2018). Changes in body composition during development mean that girls accumulate relatively more body fat while boys develop relatively greater muscle mass (Abreu and Kaiser, 2016). Figure 4 summarises the main features of puberty:

Activity 2: What body changes mean to young people

Spend a few minutes thinking about the implications of changes during puberty for young people. You might have vivid memories of your own experiences.

Discussion

You may have thought about young people becoming self-conscious about the visible changes. Girls might begin to experience harassment in public places (‘wolf whistles’ for example). Boys may feel peer pressure over penis size or their voice dropping. You might have memories of your first bra or your first facial shave (depending on your sex). There will be a whole range of implications, and they can be quite individual.

1.3 Social changes

In the opening video, Martha and Josie talk about adolescence as a time of great change and often confusion. Whilst they describe many of these changes as challenging, particularly the pressures that many friendships bring, they also reflect on adolescence as a period of excitement marked by increasing responsibilities and new experiences. During adolescence, social spheres are expanding, often coinciding with a move to larger schools and a greater range of options for leisure activities or paid work. There is a tendency to move away from reliance on adult role models (e.g. their parents and caregivers, teachers and mentors) towards an increased emphasis on striving for autonomy, individuality and self-reliance. Friendships rise in level of importance for many and young people rely more on the opinions of friendship groups for approval rather than parents and other caregivers. This need for peer group approval can however, enforce risky behaviours such as drinking alcohol or smoking cannabis (Kehily and Pattman 2006).

The centrality of friendships lasts throughout adolescence but falls off by late adolescence when the importance of belonging to a crowd or a particular group is replaced by the need to become part of a more intimate relationship. In the next activity, you’ll think about elements of adolescent relationships.

1.4 Adolescence and emotion

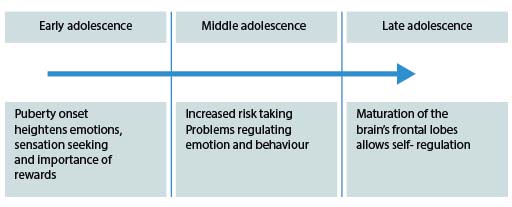

At the onset of puberty, there are clear changes occurring in the brain on a young person’s journey towards emotional maturity. As you will see in the next section, adolescence is a time of great change in brain development, with implications for how young people recognise and regulate their own emotions (Yurgelun-Todd, 2007). These changes also appear to bring about an increased risk of problematic behaviours and emotions (Steinberg, 2005).

You may remember that young people are beginning to distance themselves from their parents and caregivers. This means that adolescents may find themselves relying on their own slightly ‘wobbly’ emotion regulation capacities at a time when they are facing new social challenges.

1.5 Challenges of adolescence

In early adolescence there tends to be a heightening of emotions where young people often seek thrills and challenges (Steinberg, 2005). There is some evidence that adolescents experience greater extremes of high and low emotion (Larson et al., 1980) and that average daily mood becomes more negative between the ages of 9 and 14 (Larson and Lampman-Petraitis ,1989). Perhaps some of the stereotypes about adolescence actually contain a grain of truth!

It has also been found that having a boyfriend or girlfriend is particularly associated with wide mood swings (Larson et al., 1996) and it has been argued that this is one of the major sources of stress and emotional pain for many adolescents (Larson et al., 1999). For young people who do not identify as heterosexual (‘straight’), the emotional challenges may be even greater. The next activity asks you to consider a range of adolescent challenges.

Activity 3: Adolescent challenges

Watch the video again (from the Session 2 Introduction).

Transcript: Video 1 (repeated): Reflecting on adolescence

What do you think are the most important challenges that the young person is facing? Jot down a few notes next to each of these:

physical | |

emotional | |

social |

Discussion

Martha and Josie reflect on their own experiences during adolescence as a challenging time, characterised by intense emotional experiences, physical changes, enhanced responsibilities, increasing demands in education and learning and pressures amongst peer groups to look and behave in particular ways. They also reflect on adolescence as a period that brings new and exciting opportunities to socialise and be more independent.

Some of the most enlightening research of recent years has come from neuroscience and neuropsychology. You’ll explore many of these themes next, through a ‘neuroscience lens’.

2 The adolescent brain

Understanding more about adolescent brain development can help you to understand how to support a young person’s mental health. Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system. According to neuroscientists, adolescence constitutes a period of significant transformation in the brain. Neuroscience has advanced considerably since the late 1980s when new imaging techniques such as those you may have already heard of including CT scans and MRI scans, have allowed detailed images to be made of living brains. These images have allowed scientists to understand more about how brains function and develop.

The brain is the ‘control centre’ of the entire nervous system, which comprises nerve cells that transmit messages within the brain as well as between different areas of the brain and the rest of the body. In different parts of the brain, signals from the body are translated into perceptions, feelings, thoughts and actions.

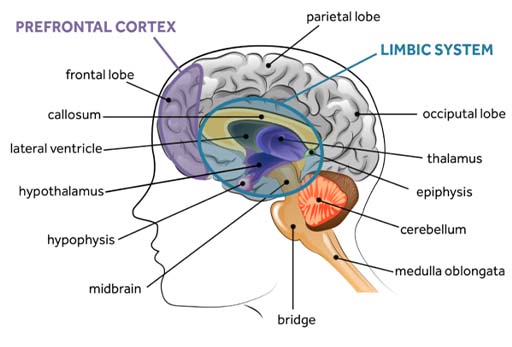

You may be aware that various areas of the brain perform different functions. For example, the occipital lobe at the back of the brain (see diagram below) is responsible for converting the nerve signals originating in the eye into images that you can perceive as ‘sight’. The two areas of the brain that have received the most attention from neuroscientists studying adolescence are:

- the prefrontal cortex

- the limbic system.

Study Figure 7 to familiarise yourself with the locations and broad functions of the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system before moving on to the next activity.

Activity 4: Brain changes during adolescence

a.

Both adults and adolescents found the task more difficult with the ‘director’ than with the ‘rules only’ condition.

b.

Only adolescents found the task more difficult with the ‘director’ than with the ‘rules only’ condition.

The correct answer is a.

a.

The ability to take someone else’s perspective in order to guide their behaviour is well developed in early adolescence.

b.

The ability to take someone else’s perspective in order to guide their behaviour is still developing in mid to late adolescence.

The correct answer is b.

Step 3: Watch the TED talk from 8.30 to 11.39 to discover the outcomes of the experiment. Then, consider for a moment how many aspects of adolescent behaviour could be a reflection of normal brain development.

Discussion

The outcomes of the experiment showed that:

- Both adults and adolescents found the task more difficult with the ‘director’ than with the ‘rules only’ condition.

- The ability to take someone else’s perspective in order to guide their behaviour is still developing in mid to late adolescence.

Hold your initial thoughts about the link between adolescent behaviour and their brains as you move to the next step.

Linking adolescent behaviour with brain development can help people accept adolescence and some of the behaviours that are displayed then as a normal process rather than see it as abnormal or deviant. Risk-taking and peer pressure are two characteristics that are strongly associated with adolescence, and you’ll consider these further next.

2.1 Peer pressure and risk taking

You have already learned about an experiment, in which two different ‘conditions’ (the ‘director’ and ‘rules only’) were tested with different age groups.

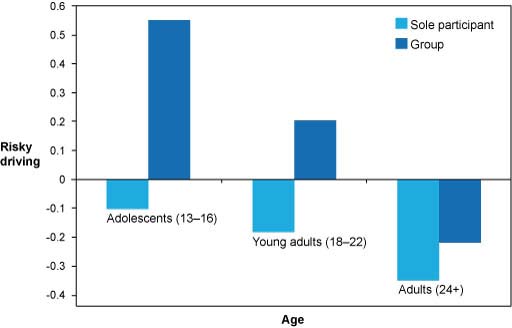

Psychologists Gardner and Steinberg (2005) conducted an experiment to explore age differences in risk taking. They asked their participants to play a computerised driving game in which they were able to take risks (e.g. driving through an amber or red light) in the pursuit of accruing points, with the aim of getting as many points as possible. They split participants into three age groups (13-16, 18-22, 24+) and assigned them randomly to one of two conditions – playing alone or in the company of two age-matched peers.

Their findings (see figure below) demonstrated that risk taking was greatest in adolescents in the company of their peers, followed by adolescents who were alone. Young adults took greater risks when with their peers, although this was of a lower magnitude, and adults took fewest risks both when alone and with peers.

This study appears to demonstrate that peers have an important role in adolescent risk-taking, and supports the assertion that peers become of greater significance during adolescence. This is, of course, a laboratory-based study and how this relates to actual real-world processes is unclear.

It is still not well understood how an individual’s experiences and behaviours may influence their brain development, or what the implications of certain experiences or learning opportunities in the adolescent period are for the subsequent adult brain. This area of brain development is known as ‘experience-dependent plasticity’ (Dow-Edwards et al., 2019, p. 2). ‘Plasticity’ refers to the ability of the brain to adapt its structure and function in response to accumulated experience and behaviours. A classic example of plasticity is learning to play a musical instrument, in which the nerve pathways involved in controlling movements, reading music and listening to the sounds produced, are reinforced with practice (Herholz, 2012).

Research focusing on the effect of alcohol or drugs on the developing adolescent brain has revealed that these substances can interfere with normal brain development (Dow-Edwards et al., 2019; Spear, 2018). It may be encouraging to know that there are signs that young people are beginning to reject social pressures to drink alcohol (Larm et al., 2018; Vieno et al., 2018). In the next section, you’ll consider some of the other challenges of social pressures.

3 The social world of adolescence

The social world of adolescents is central to their health and wellbeing. It can make young people feel vulnerable as well as provide opportunities for support. In this section, you will consider vulnerability in more detail.

In the opening activity, you will reflect on the social context of adolescence, the pressures it places on young people, and how they might respond.

Activity 5: Identifying sources of pressure

a.

Managing friendships

b.

Family relationships

c.

Romantic relationships

d.

Exam pressures

e.

Health concerns about self or others

f.

Lack of clear career motivations/ambitions

The correct answers are a, b, c, d, e and f.

Discussion

It is worth bearing in mind that even if a young person seems to be sailing through life and coping well, there’s a good chance they will still be experiencing a significant number of social pressures. A young person who is clearly having difficulties is more likely to need some support to manage them, and you will find out more about this in Session 6.

Some social situations can be difficult and challenging. You’ll consider the challenges of bullying and loneliness next.

3.1 Bullying

Bullying is an extreme form of social pressure.

According to Bullying UK (2019), bullying can be defined as: ‘repeated behaviour which is intended to hurt someone either emotionally or physically, and is often aimed at certain people because of their race, religion, gender or sexual orientation or any other aspect such as appearance or disability.’

If you have any experience of bullying, you will appreciate that bullying can be subtle, cumulative, and not easy to describe to someone. The bullies themselves may be struggling to handle their own situation. In the next activity, you will watch a video created by young people who have experienced bullying.

Activity 6: Anti-bullying campaign

Watch this anti-bullying campaign video and make a note of the main message you take from it.

Discussion

The video expresses some of the ways in which a person can feel the effects of bullying, e.g. blame, manipulation, insecurity. It also makes clear points about the links between bullying and mental health (of both the victim and the bully).

Bullying is a common experience. A large Canadian study on the extent of bullying in young people found that 58% of girls and 68% boys had experienced some form of bullying during a year (Salmon et al., 2018). Types of bullying included physical threats or injuries, ridicule, saying something bad about their race or culture or sexual orientation or their appearance, and applying pressure in social media. Cyberbullying can be particularly difficult to escape as it can spread rapidly through social media (Hill et al., 2017)

Bullying can be particularly hurtful in the context of adolescence where peer relationships are so pivotal. Loneliness can also inflict pain in adolescence, and you’ll explore this next.

3.2 Loneliness

Adolescents are driven to form friendship groups, from which they gain a sense of belonging and in which they can form their own sense of identity. Feeling ‘left out’ for any reason can lead to loneliness. Loneliness research is an important area for improving understanding of how to help young people who are experiencing loneliness. According to UK (England) statistics, about 10% of 16 to 24-year-olds report feeling lonely ‘often/always’ and 23% report feeling lonely ‘some of the time’, which is significantly greater than people in older age groups (ONS, 2018). Comparable figures are not available for those under 16.

Research carried out during the COVID pandemic indicates how many children and young people find social isolation exceptionally difficult and challenging to their mental health and may add to many worries they have about their own health and the health of their loved ones.

You can read more about the impact of the COVID pandemic here (remember to open these links in a new tab or window, so you can return to the course when you are finished):

- Teenagers’ mental health under severe pressure as pandemic continues - new research

- Pandemic takes toll on young’s mental health, says report

- The impact of COVID-19 on linguists and their mental health

- Grief and COVID-19: Mourning what we know, who we miss and the way we say goodbye

- Five ways in which COVID-19 has impacted on progress in global health

- Coping in isolation: Time to Think

- How can Adult Carers get the best support during Covid-19 pandemic and beyond?

- How does COVID-19 affect cancer treatment?

Later in this course you will also have the opportunity to hear about young people’s experiences during lockdown and the impact of COVID on adolescent mental health.

Loneliness researcher Gerine Lodder has given a TED talk on adolescent loneliness. To get a sense of a young person’s experience of loneliness, work with the video in the next activity.

Activity 7: the experience of loneliness

Step 2: Continue watching Video 4 to 4.32 minutes. Notice what Gerine Lodder says about the effects of loneliness on a young person’s health.

Discussion

Loneliness affects young people’s mental health, causing depression and lower self esteem. It can also affect physical health and wider success in society. We should pay attention to our children’s social health, because it has an impact on everything else.

Later in this course you will focus on the different strategies and approaches that can be used to support a young person who is experiencing mental health difficulties perhaps in relation to feelings of loneliness and bullying.

You have covered a lot of ground so far, thinking about the characteristics of adolescence. In the next section, you’ll consider the implications of all this in relation to how people might set the limits on what is ‘normal’.

4 What’s ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’?

Adolescence is often viewed very negatively, with young people seen as out-of-control, irresponsible, threatening, lazy, discontented, sexually obsessed, naive and difficult to deal with. A young person is often seen as a troublemaker or as a nuisance who must ‘grow up’. They are sometimes discriminated against in a way that would be unthinkable for other sections of the population – banned from shopping centres, for example, not because they have been proved to be troublemakers but because of the assumption that they will cause difficulties. This sense of social exclusion is another challenge that young people have to face, and the dislike of young people that is sometimes expressed indiscriminately in the media also contributes to adolescents’ identity, albeit in a negative way. It is important to note that concerns about the behaviour of young people is not new. For example, in the 1960’s there was a lot concern about the behaviour of members of the youth subcultures the ‘mod and rockers’, such that Stanley Cohen (1972) described it as a ‘moral panic’ in being a sensationalist and over the top reaction. In the 1990’s there was a similar panic about EMO pop bands which were thought to encourage young people to undertake acts of self harm.

Earlier in the course, you found that many young people today seem to be experiencing an increase in mental health problems. What is certainly clear is that there has been an increasing concern in the media and elsewhere about young people’s mental health, resulting in a range of reports and initiatives. Take a look at these headlines:

It can be difficult to know when a young person needs help, and what kind of help they might need. In the next activity, you will engage with an interactive case study to see how well you are able to recognise a problem and assist a young person.

4.1 Recognising a problem

For this activity, it’s not about getting it right - it’s about exploring different ways of understanding young people and the different approaches that can be used to support them.

Activity 8: Helping Lily and Ethan

Go to the opening page of the interactive case studies, and select either Lily or Ethan. Work through the whole activity with one of them.

Discussion

Did you identify the issues Lily or Ethan were dealing with? If you have time, you might want to repeat the activity with the other case.

Are you any closer to deciding what a ‘normal’ adolescent looks like? Changes in the brain, which are independent of cultural judgements about adolescence, indicate that you can expect swings in emotion, a greater tendency to take risks, and immature decision-making abilities as the norm. You might expect more arguments as adolescents test their social boundaries. When young people reach a point where they become unable to function in a way that promotes their longer-term health and wellbeing, you may have cause for concern. Some of this ability to cope with difficulties will be discussed in Session 5, which is about resilience.

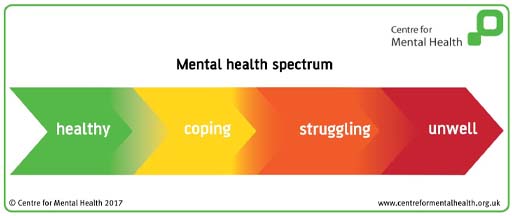

Mental health difficulties, similarly, become a cause for concern when the young person is struggling to cope. The diagram below, produced by the UK Centre for Mental Health, shows a spectrum in which there may be no clear dividing line between the transitions from trouble-free mental health, a situation where a young person is coping well with challenges, to points where they struggle or become unwell. As you continue through this course, you’ll refer to this spectrum periodically.

5 This session’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’ve finished.

6 Summary of Session 2

The main learning points of this session are:

The long-standing idea that adolescence is a time of crisis (or ‘storm and stress’) is partially supported by more recent research although it is also evident that the influences on adolescent are complex and cannot be reduced to such a generalisation. Adolescents are living through changes in their bodies, their social world and the ways in which their emotions guide their behaviours.

Brain changes during adolescence, which have been discovered by the use of MRI and fMRI imaging, affect the way adolescents make decisions and learn. During this time of transition, young people may engage in risk-taking and become more receptive to peer pressure. Brain plasticity means that this is a good time for learning as well as susceptibility to the effects of alcohol and drugs.

Sources of difficulty in the adolescent’s social world include bullying and loneliness, which are heightened by the drive to feel a sense of belonging to friendship groups.

There is no clear dividing line between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’. Encouraging young people to talk about what is happening in their lives can help them to cope and make healthy decisions.

Now go to Session 3.

Glossary

- Adolescence

- Adolescence is a transitional stage of physical and psychological development that generally occurs during the period from puberty to adulthood. Adolescence is commonly associated with the teenage years.

- CT scans

- CT (computerised tomography) scans use X-rays to form images inside the body.

- MRI scans

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) uses magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses to produce detailed pictures of organs and internal body structures.

- Psychologist G. Stanley Hall

- G. Stanley Hall was a leading American psychologist with an expertise in child development and had a particular interest in adolescence.

- Resilience

- Rather than being fixed during the early years of life, neuroplasticity describes the brains capacity to adapt in response to environmental influences.

- Storm and stress

- Storm and stress is a phrase used by G. Stanley Hall to describe the turbulence of adolescent development.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Victoria Cooper, Sharon Mallon and Anthea Wilson and was published December 2021. We would also to thank Jennifer Colloby, Steven Harrison and Karen Horsley for their key contributions and critical reading of this course. We would like to thank the parents, young people and professionals who shared their experiences with us.Their willingness to share sensitive and highly personal accounts of having or supporting those with mental health challenges adds greatly to this course and we will hope will benefit all those who find themselves in similar situation.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below (and within the course) is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Session 2: Understanding Adolescence

Figures

Figure 1: GoodStudio/Shutterstock.com

Figure 2: Frederick Gutekunst (1831–1917) Blue pencil.svg wikidata:Q1452890 https://commons.wikimedia.org/ w/ index.php?curid=1292633

Figure 4: from: Abreu, A. P. and Kaiser, U. B.(2016) ‘Pubertal development and regulation’, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol 4, no. 3, pp. 254-264.)

Figure 6: Kevin the Teenager (from BBC comedy) Tiger Aspect Production/ ©BBC

Figure 7: adapted ©Viktoria Kabanova|Alamy Images

Figure 8: Purestock/Alamy Stock Photo

Figure 9: adapted from Gardner, M. and Steinberg, L. (2005) ‘Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: an experimental study’, Developmental Psychology, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 625–35.

Figure 10: ©John Birdsall/Alamy Stock Photo

Figure 11: ANDY HARMER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Universal Images Group

Figure 13: ©Centre for Mental Health https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/ mental-health-among-children-and-young-people

Audio/Video

Video 1: Reflecting on Adolescence: Martha and Josie: © The Open University

Video 5: Gerine Lodder | TEDxGroningen TEDx Talks https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-nc-nd/ 4.0/

Video: Activity 8 created by The Open University using Elucidate software under licence

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – The Open University.