Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 21 November 2025, 7:40 AM

Session 3: Mental health promotion and education

Introduction

On one hand, there are many complexities surrounding our understanding of children’s mental health and appreciating the reasons why a number of children are experiencing poor wellbeing and compromised mental health. On the other hand, it may also be helpful to recognise that there is a great deal that adults can do to improve children’s wellbeing, promote good mental health and consequently prevent serious and enduring mental health conditions in young children.

In this session, you will explore what is meant by ‘mental health promotion’ and how improvements in terms of education and understanding in relation to mental health can help us to support and promote mental wellbeing in children. You will also explore the foundations of ‘good mental health’, and the theories that underpin current beliefs and approaches.

Now listen to the audio introduction to this session.

Transcript: Audio 1

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- understand what is meant by mental health promotion and education

- explore some of the key ingredients of ‘good’ mental health in young children

- reflect on the main components of attachment theory

- consider the effects of attachment relationships on young children’s mental health and wellbeing

- examine ways to prevent and minimise the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

- have an awareness of how perseverance and resilience can be promoted in the early years.

1 Understanding mental health promotion and education

Health promotion in relation to physical health has been recognised as a powerful way of potentially preventing health conditions and diseases.

Preventing the causes of illnesses such as infections, heart disease and cancer is, as the old saying goes, ‘better than cure’. Health promotion requires people to be educated about the causes of health conditions so that they can learn how to adapt their behaviours in order to decrease their risk of developing a condition. In a similar way to promoting physical health, mental health can also be promoted.

1.1 Mental health promotion

Messages about promoting health through exercise, healthy eating and avoiding high risk activities such as smoking are very actively promoted, from bus stop posters to national advertising campaigns, and hence are part of everyday life. In a similar way to promoting physical health, there are many activities that can promote mental health. These include:

- reducing and adaptively managing stress

- engaging in enjoyable activities and hobbies that increase our wellbeing, such as walking

- developing and maintaining positive relationships with people

- getting sufficient sleep.

Adults can more easily make a conscious decision about their readiness to engage in activities that promote their physical and mental health; in fact, some activities are equally beneficial for both aspects of health. Engaging in such activities can prevent, or at least reduce the chances of developing health problems such as heart disease, diabetes and certain mental health conditions.

1.2 Promoting mental health among children

To some extent, adults have a choice about whether they accept the health promotion messages that surround us. This is not to say that ‘choosing’ to follow a ‘healthy way of life’ that contributes to the prevention of some illnesses is straightforward. Far from it. The business of life – in particular personal circumstances and where we live – can make it difficult or even impossible to afford taking up a hobby, or being able to relax and go for a walk in a safe environment. However, most adults will have some level of control over their health-promoting behaviours, and even though it may be difficult to make certain changes, there is often some scope to do so.

For young children, their choices about what they can do to shape their lives in ways that maximise their physical and mental health are rather limited. Young children may not have the vocabulary to recognise and express their feelings, so emotional responses to situations can be expressed as ‘bad behaviour’, when in reality, the child is expressing their emotions, which may include feelings of frustration, sadness or anger, in a way that is expected at their age and stage of development. Young children also have very little control in relation to where they live, who they live with and, often, considerable restrictions about what they do. Consequently, the adults in children’s lives play a critical role in creating environments for children that are positive for their mental health. However, there is much to do to enhance people’s understanding of how this can be achieved.

1.3 Health education about young children’s mental health

During recent years, there has been growing awareness of the importance of addressing the mental health needs of adolescents, especially when they are presenting during a mental health crisis. As the twenty-first century has progressed, greater attention has been given to young children’s mental health, including infant mental health. The national curriculum in many countries has included statutory guidance about school-aged children’s personal, social, health and emotional aspects of education and development. This is an important part of the education of professionals and children about good mental health and you will explore this further in Session 5. However, there is still a need to develop messages that help to educate adults about young children’s mental health and this is especially so in relation to babies and very young children.

Several initiatives have been created to promote awareness and educate adults about the importance of infant mental health. For instance, in England, the charity Parent Infant Partnership UK was set up in 2012 and does extensive work to educate and increase awareness of the role of parents, professionals and society in developing good mental health for babies. The website has a great deal of useful information: a link is provided in the ‘Further reading’ section at the end of this session. Similar initiatives are also in place in Australia and the United States; for example, Zero to Three (a link is provided in the ‘Further reading’). You will explore the global concern of young children’s mental health further in Session 4.

So, what are the ingredients that contribute to the development of good mental health in babies and young children? You will focus on this in the next section.

2 The ‘ingredients’ of good mental health and wellbeing in young children

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) is regarded as a pioneer in advancing knowledge of the significance of relationships in early childhood and what supports the development of good mental health across the lifespan. Freud was working in the late part of the nineteenth and first part of the twentieth century. This illustrates how recently the theories and research have been conducted that inform our knowledge of what humans need to promote good mental health. Freud’s work was considered pioneering because the origins of current understanding and practice can be traced back to him (you will explore this further in the next session).

Part of Freud’s legacy was his belief that early childhood experiences ‘shape us’ and are fundamental to determining what is likely to happen in later life. In the next section, you’ll look at the ‘ingredients’ for good mental health in childhood.

2.1 A recipe for good mental health

It might be helpful to regard the factors that contribute to good mental health in childhood as a recipe. This analogy is useful because a recipe gives a list of ingredients and instructions on how to prepare something to eat. As we all know, recipes can be slightly different, depending on which cookbook or website you use. Likewise, the context of a child’s life may require different ingredients, as well as some creative problem solving (like ‘substitution’) should an ingredient not be available. But even when we use the ingredients and follow the instructions, sometimes the results can be unexpected for a range of reasons, either in a good or not so good way.

Activity 1 What are the ingredients of good mental health for babies and young children?

Reflecting on what you already know and what you have learned in the course so far, write a list of the ingredients that you think are likely to be a ‘recipe’ for good mental health for babies and very young children.

Discussion

When compiling your list of ingredients for good mental health and wellbeing, you may have included some of the factors from Session 1, Activity 2, such as resources within the child, family, community and society. You may have added ‘love’ as a key ingredient, but how would you quantify that? In particular, what actions or behaviours would indicate to a child that they are loved? It may be helpful to look back at your response to this activity.

However, as the course has progressed, you may also have increased your knowledge about the role of adults in promoting the mental health of young children. An important way that this can be achieved is for the adult to understand children’s development, and to be aware that some unacceptable behaviour can simply be quite typical of the child’s age or stage of development (e.g. tantrums).

One ingredient stands out as being the foundation of good mental health: the early formation of a stable, containing, unconditional and positive relationship. This assertion is based on the theory of attachment. In the next section, you will explore the theory of attachment and why it is so important in helping our understanding of young children’s mental health.

2.2 Attachment theory: what is attachment?

When explaining the original theory of attachment, psychologists and others have suggested that babies are born with a biological need to be physically close to an adult for survival and protection. They are therefore very dependent on significant adults being both physically and emotionally available to take care of them. These early relationships with adults shape the way children learn to trust others, as well as their understanding of how relationships work and their feelings about themselves. The basic need for young infants to feel safe and secure which encourages closeness with adults can lead to a range of behaviours that foster closeness, such as smiling and cuddling attachment figures. Other behaviours like crying and being clingy can also occur when an infant becomes distressed, and it is usually the primary attachment figure that can soothe the child. These are considered to be instinctive behaviours. Crying and becoming clingy can also be attempts to communicate an infant’s anxiety and distress when they fear separation (which is usually only for a short period).

Activity 2 Understanding the continued need for attachment as adults

In order to appreciate how we may feel emotionally more secure with some people rather than others, make a list of some of the main qualities that exist in people you trust and feel closest to.

Discussion

When you look back over your list of qualities it would be interesting to reflect on how many of these revolved around communication, the way they respected your thoughts and feelings, and how well they listened to what you had to say without making too many judgments. In psychological terms such an approach, which is also the cornerstone of any counselling relationship, is called ‘unconditional positive regard’ (Rogers, 1951). In other words, the person is still positive towards you – warts and all! That does not mean they condone or agree with all your behaviours and attitudes. Rather, they are giving you time and an emotionally safe space to be yourself.

Many children who have not had the opportunity to develop close, responsive relationships in early childhood may not have experienced such unconditional positive regard or been accepted for who they are. They may therefore have never felt what it might be like to have their feelings validated or be comforted when distressed. They may never have felt sufficiently safe and secure enough to relax, play and learn in the same way as other children because they have not had a consistent and stable primary attachment figure.

2.3 Background to attachment theory

John Bowlby developed his attachment theory when working as a psychiatrist at the Tavistock Clinic in London in the 1950s. His work focused mostly on children who had been separated from their parents (particularly mothers) in early childhood due to circumstances such as prolonged hospital stays, or children who were living in residential institutions. It is important to set Bowlby’s work in the UK within the time frame following the Second World War, when many children had lost parents or were temporarily separated from them. These issues were discussed in Session 1 and particularly in the case study of Sheila, the evacuee.

The reason why Bowlby’s ideas were so groundbreaking was that for the first time the psychological and emotional wellbeing of young children was being placed ‘centre stage’. Today it can be hard to realise that care settings did not consider such issues to be equally as important as children’s physical health.

As a consequence of Bowlby’s work, various policies and practices changed for the better, such as hospitals allowing parents to visit their sick children, which today is taken for granted. There was also a greater emphasis on examining the quality of relationships between adults and children in institutional settings, which is now seen as a key indicator of how well an early years setting is functioning.

Since Bowlby’s original work, there has been a great deal of controversy around some of the statements he made in relation to the role of mothers as the main caregivers. He did not fully appreciate the wider family and care network that a young child might have. For example, some children are not raised by their mothers and are ‘perfectly well adjusted’, because other adults have been their primary caregivers and attachment figures. Originally, he stressed the need for mothers, as significant carers, to stay at home in the early years of a child’s life in order to avoid the development of future mental and emotional problems.

Even today there are many different opinions that arise about the extent to which significant carers should remain at home in the early years of a child’s development, and also the age at which young children should attend more formal early years settings. Despite the debates around Bowlby’s work, it is still significant and continues to influence our understanding of the importance of attachments for children’s social and emotional development.

2.4 The importance of attachment theory

Attachment continues to be an important psychological idea that helps to describe the quality of the relationship between the child and key caregivers in a variety of different care settings.

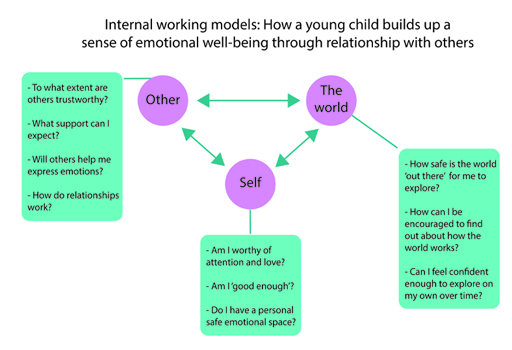

The most effective way to visualise attachment is as a process. Through the development of close, caring and positive relationships in childhood, a young child can build up an effective internal set of ideas or what has been called an ‘internal working model’ (Bowlby, 1969) of how they see themselves, how they interact with others, and also how they develop their own sense of who they are and who they can become within the social world around them.

Figure 5 is a diagram showing the interconnections between self, other and the world in order for the young child to build up an internal working model of how relationships work.

Reflecting on the diagram and the questions that might be asked or addressed through different interactions, you might notice how different ways of being attached or connected to significant others, especially as a young child, will have an enormous effect on that child’s perceptions. The components and quality of the different interactions will not only affect how the child perceives themselves and their own value in the world, but also whether they believe they are ‘worthy’ of affection and care from others.

Therefore, a young child who has experienced consistent and warm, loving connections with significant caregivers who have been attuned to their emotional needs will have been given ‘positive acceptance’ for who they are. They are then more likely to grow up feeling they are ‘worthy’ in terms of long-term relationships, in particular intimate relationships, and will be able to express their emotions more openly. They are also better prepared to make positive contributions to relationships with others in the future. The emotional security they experienced as a child is likely to lead to a greater understanding of a range of emotional reactions to different situations. Infants that are securely attached are not only more likely to have greater empathy for others, but also higher tolerance of being left alone for longer periods of time, away from significant others.

2.5 Emotional containment

Emotional strength involves the ability to express and accept a range of different emotions that might be experienced in a variety of circumstances. A child’s emotional wellbeing can be influenced by the ways in which their feelings are accepted by significant adults in their lives. This process of accepting emotions, being able to hold them, is called emotional containment.

For example, if emotions such as anger are perceived by the adult to be almost exclusively inappropriate or undesirable, then a child may well learn to avoid adequately expressing such feelings. For example, many girls are actively discouraged even from a young age to express their anger (as this is not ‘ladylike’). Conversely, many boys are actively discouraged from expressing feelings of sadness (because ‘boys don’t cry’). However, such habitual avoidance could build up greater frustrations and even lead to lower levels of emotional resilience or alternative forms of emotional expression (e.g. a boy’s angry outburst when the underlying emotion is sadness).

In contrast, parents and carers who are able to adequately contain children’s emotions and facilitate their emotional regulation (even when these can be difficult to tolerate at times) can help to nurture qualities such as emotional resilience. Adults can also help the child to see that even when they are angry, upset or frustrated, they will be heard and validated.

Furthermore, contrary to what might seem like a natural instinct to ‘take over the situation’ in order to protect the child, all that might be necessary is for the adult to patiently take the role of an alert observer, actively watching and listening to what the young child is attempting to express. Ultimately, all behaviour – however challenging at times – can be seen as an attempt at communication of some kind; finding out what the child might be distressed about is key to helping them to develop greater emotional resilience.

Sometimes adults feel they need to ask a range of questions and they can have an ‘intense interaction’ with a child in order to find out what the problem is or how best they can help. Such strategies can often be extremely intimidating for the child. A more non-intrusive way can be through play or other joint fun/social interaction, which can help to diffuse or lessen anxieties – as long as the child feels ready to engage. Through such activities, the adult can help the child make sense of how they are feeling, even if they do not yet have the vocabulary to describe this using words. Both adult and child can then work together to negotiate ways to react differently to similar situations in the future.

3 The effects of attachment relationships on young children’s mental health and wellbeing

In relation to attachment theory, the quality of the relationship between the caregiver and young child can influence how perceptions and ideas are built up over time by the child. These ideas then form the basis of how to respond in future social relationships. If they have experienced positive, warm and loving early care, they are more likely to feel secure and worthy of love and attention from others – and be able to give others love and attention. However, experiences of being perceived to be unloved and/or rejected could lead to a child avoiding contact with both adults and other children. Excessive anger and confusion in early childhood could create a greater resistance in the child as they may become increasingly anxious and unclear about what adults and others expect of them, or whether other people can even be trusted or not.

Activity 3 What can influence the development of secure attachments?

Jot down at least three different influences on early childcare that might have a negative impact on a child developing a secure attachment relationship.

Then think of three influences that might lessen these negative impacts.

Discussion

In terms of negative influences, you may have considered the poor mental or physical health of the carer. For example, depression or chronic illness could mean that carers may struggle to be emotionally available and responsive to the child. Parenting styles are also thought to be very important, whereby neglectful (characterised by uninvolved and disinterested parenting) and authoritarian (parenting with limited affection and harsh punishments) styles of parenting are associated with insecure attachments

However, if the carer has a good support network, caring for the child can be shared with other members, allowing more opportunity for the child to develop a wider variety of positive ‘internal working models’ around how relationships work. That is because a child can have multiple attachment figures, and an attachment figure that adopts an authoritative style (i.e. care that is responsive to the child’s emotional needs and also sets high standards for the child) for a child means that they are still likely to develop a secure attachment.

You will explore adverse childhood experiences in more detail later in this session.

3.1 Transitioning from home to other early years settings

The quality and nature of relationships that young children develop with significant others in the early years can help or hinder the ways in which they then cope with day-to-day changes in their routine and being away from home, as well as longer-term transitions from home to other early years settings. It is also important to remember that even securely attached toddlers can be affected if they are in a daycare provision where the quality of sensitive responsivity and attunement to the child’s wishes, views and how they express themselves leaves much to be desired.

You will explore the creation of environments that are conducive to supporting early transitions as effectively as possible in Session 5.

Activity 4 Attachment and transition to daycare provision

Read the following case study, which is based on a child that the author of this course has worked with, and then reflect on the questions that follow.

Case study: Danii

Danii, who is 3 years old, is looked after by her mother and her grandmother (‘nan’). Her parents separated when she was 2 years old. Her mother then had to increase the number of hours she works in order to enable the family to continue renting their current accommodation, pay the bills and buy food and clothing. Danii then spent a great deal of her day in the care of her nan and grandfather (‘gramps’). She was very fond of her gramps, but he died recently.

Danii is loved and well cared for and, whenever possible, given plenty of positive attention. As the only child, she is often in the company of adults and some of the older children in the wider family network who treat her as their adored ‘baby’ girl. However, she has not had much opportunity to spend time with other children her own age.

Danii’s grandmother is beginning to have various health problems. On the advice of a GP and the health visitor, Danii is now to attend an early years daycare provision for three mornings a week to see how she gets on.

The first morning was very challenging for her grandmother; Danii would not leave her side at all, clinging to her and seeming to be very anxious and afraid. She also turned away from staff whenever they gently attempted to interact with her. Eventually, her nan said she had to go shopping, but would be back very soon to take Danii home. However, Danii would not go to any of the daycare staff or towards any of the toys once her nan had left. She ran and hid under a table and started to cry inconsolably, saying she wanted to go home.

- How do you think Danii’s responses can be explained through attachment relationships she has developed so far?

- Imagine you are a member of staff: what do you think your next move might be?

Discussion

You probably reflected on the close relationship that Danii had already built up with both her grandmother and grandfather. You might also have put yourself in Danii’s shoes, imagining how she felt going to a strange place for the first time. She was perhaps fearful about leaving her nan, bearing in mind that she has only recently lost another significant person in her life – her grandfather (‘gramps’). Her clinging to her grandmother for so long highlights how, although feeling secure with her nan, she is not confident enough at this point to explore new places and interact with new people, even with her grandmother in close proximity.

In running to hide under the table, Danii was perhaps attempting to find a safe place where she would not be disturbed and have time to be on her own. Of note, given her young age, and very limited experiences of being cared for by people outside her family, her response is perhaps less pathological or extreme than you might think. It is not unusual for a 3 year old to find a transition like this difficult, although Danii’s responses here do require careful monitoring.

So, what actually happened next? The staff did not immediately go to Danii and intrude in her space or attempt to physically comfort her. All such actions she may well have found very intimidating. Instead, one member of staff (who later became Danii’s key person) sat near the table, on a level with Danii, gently handed her cushions and blankets so she could make up her own ‘den’, then quietly watched and waited for Danii’s responses. In this way, Danii was being accepted as a child who could express her emotions and have control over what she then decided to do in her own time, without feeling pressured to meet external expectations or do things she did not want to do.

The case study of Danii illustrates how her key person helped to support Danii to make her feel better without overwhelming her. Danii had experienced a number of adverse experiences, but what are adverse childhood experiences? The next section explains more about what is meant by ‘adverse childhood experiences’ (ACEs).

4 Preventing and minimising the impact of adverse childhood experiences

There is no one definition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), although most attempts define the term as events in the early years of a child’s life that may have a negative impact in childhood and adulthood. Michael Rutter described adverse experiences as ‘the circumstances of early childhood that can cast a long shadow’ (1998, p. 16).

The next activity asks you to consider the experiences that children may be adversely affected by.

Activity 5 Identifying adverse childhood experiences

- List the experiences that may occur in childhood that you think could be considered as adverse.

- Now watch the six-minute video below, made by the Wave Trust to explain ACEs and highlight how they can impact on childhood and into adulthood. The film is animated, but it does contain some information that may be upsetting. As you watch, consider your notes alongside the experiences mentioned in the video.

Transcript: Video 1 What are adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

[SHOUTING]

[GLASS BREAKING]

[SHOUTING]

[SIREN]

[SHOUTING]

[DOOR SLAMS]

[FLATLINING]

Discussion

The video highlights how a combination of family circumstances and behaviours, described as ACEs, can become a ‘toxic mix’ for children. You may have found the first two minutes of the video very negative, as if it is inevitable that there will be difficult long-term consequences for children who experience adverse childhood experiences. However, the second half highlights that this is not necessarily the case. The video shows that help in early childhood can avoid negative long-term consequences, noting that it is the responsibility of all professionals – such as teachers, police and health professionals – but most of all parents, to do what they can to support children and prevent them from experiencing ACEs. A primary function of parenting is to provide protection. In addition to shielding and protecting children from ACEs, it is also important to help children to develop resilience.

The next section explores how perseverance and resilience can be promoted in childhood.

5 Promoting perseverance and resilience

As with many psychological concepts, there is not a single definition of what is meant by ‘resilience’. The term should be viewed as more than the individual child’s ability to ‘bounce back’ from adverse or difficult circumstances. There are factors that support the development of resilience in children.

5.1 Factors that support the development of resilience in children

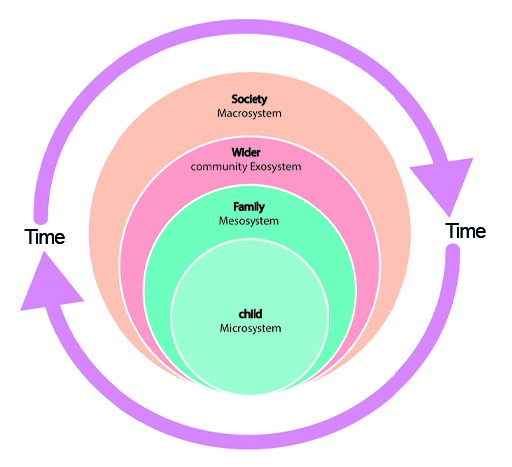

The factors that can support the development of resilience in children can be examined by looking at the systems around the child, as illustrated in the diagram that you have already seen in Sessions 1 and 2.

The following highlights some of the factors that can affect how resilience can develop within each of the systems, starting with the child.

The child

There are some factors that can help or hinder the development of resilience in children which are briefly described below:

- Temperament: can be defined as the inborn traits that influence the child’s approach to the world. If a child has an ‘easy’ and ‘outgoing’ temperament, they are perhaps more likely to quickly develop positive relationships. On the other hand, a child who is ‘slow to warm up’ and ‘timid’ may avoid social situations, struggle to develop peer relationships and play alone more frequently.

- Health: a child with a ‘strong constitution’ may join in many physically challenging play experiences, both indoors and outdoors, so they will more easily develop their motor confidence and subsequently have more opportunities to develop resilience through the freedom to explore their environment. They will also feel more able to set themselves personal goals, achieve them and then extend their range of skills.

- Disability: depending on the impairments experienced, a child with a disability may take longer than their peers to adjust to new situations or to learn new skills. For example, children with autism may have higher levels of anxiety in response to new social situations and their behaviour can be off-putting to other children, which can affect the development of peer relationships.

The family

Resilience in children can be fostered if the family or carers can provide a ‘secure base’ for children. A secure base means providing children with love and consistent routines. This facilitates emotional regulation, fosters learning opportunities, promotes social interaction and the development of friendships with other children.

The community

The wider resources that are available in the community can help children to promote resilience by providing opportunities to explore and play. For instance, playgrounds in the local community are an invaluable way of providing opportunities for children to play and explore and develop their social, emotional and physical skills.

Society

The status of children in the society they are growing up in is important in the development of resilience. If children’s rights are recognised and upheld, it is more likely that they will be given opportunities to express themselves and make developmentally appropriate decisions about their lives. They can develop greater feelings of trust and become more resilient when faced with challenging circumstances. However, not all societies regard children as having rights. As you will explore in Session 4, childhood is perceived in different ways. These different perceptions impact on how children cope with adverse conditions and develop resilience.

6 Personal reflection

At the end of each session, you should take some time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and how it has helped you to understand more about children’s mental health. The following questions may help your reflection process each time.

Activity 6 Session 3 reflection

- What did you find helpful about this session’s learning and why?

- What did you find less helpful and why?

- What are the three main learning points from the session?

- What further reading or research might you like to do before the next session?

7 This session’s quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of Session 3. You can now check what you’ve learned this session by taking the end-of-session quiz.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window and come back here when you have finished.

8 Summary of Session 3

Now that you have completed this session, you will hopefully have gained an understanding as to why mental health promotion and education is important. You have also looked at the ‘ingredients’ of good mental health. You may now have a visual overview of the processes involved in attachment, and what is meant by emotional containment. The activities should have helped you to think about how early support can lessen the long term negative effects of adverse childhood experiences.

You have also started to explore early childhood transitions from home to other care settings and how these might be managed. You have also been introduced to the concept of resilience, and how the development of a child’s resilience is affected by different interactions and influences within the different systems around the child that you first encountered in Session 1.

You should now be able to:

- understand what is meant by mental health promotion and education

- explore some of the key ingredients of ‘good’ mental health in young children

- reflect on the main components of attachment theory

- consider the effects of attachment relationships on young children’s mental health and wellbeing

- examine ways to prevent and minimise the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

- have an awareness of how perseverance and resilience can be promoted in the early years.

In the next session, you will focus on a more global view of children’s mental health and wellbeing. You will consider how wider geographical, social, cultural, economic and political factors can have a huge impact on how children are perceived and also the lives children lead.

You can now go to Session 4.

References

Further reading

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Jackie Musgrave and Liz Middleton. It was first published in October 2020.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Images

Figure 1: Artur Szczybylo; Shutterstock.com

Figure 2: weniworks; Shutterstock.com

Figure 3: Oksana Kuzmina; Shutterstock.com

Figure 4: Everett Collection; Shutterstock.com

Figure 6: Yanik Chauvin; Shutterstock.com

Figure 7: Papa Annur; Shutterstock.com

Figure 8: Rawpixel.com; Shutterstock.com

Audio-visual

Video 1: Courtesy of WAVE Trust; https://www.wavetrust.org

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University.