Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 8:24 PM

Unit 3: Participation in sustainable pedagogies

Introduction

Welcome to Unit 3 of Sustainable pedagogies.

In the last unit you were introduced to ideas around compassion as a pedagogy. This unit will extend these ideas to explore the notion of sustainable pedagogies involving learners as meaningful participants.

The unit starts by exploring what is meant by participation in educational settings.

Remember, to obtain your digital badge, you must have posted a contribution to at least one forum discussion in Units 1–7 and one of the forum discussions in Unit 8. You must also have completed the quiz at the end of Week 5 and scored at least 80%.

The items labelled ‘Explore’, which have the binoculars ![]() icon beside them, are optional and are offered for those who want to explore the ideas being discussed further.

icon beside them, are optional and are offered for those who want to explore the ideas being discussed further.

Next go to Unit 3 learning outcomes.

Unit 3 learning outcomes

By the end of this unit you will have:

- Critiqued the definitions and types of participation.

- Articulated why participatory learning is central to sustainable pedagogies.

- Developed ideas for participatory learning in your own context by exploring case study examples.

Activity planner

| Activity | Task | Timing (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | Participation for community (people, environment, policy) benefit. Reflecting on case study and applying participation to own practice. | 30 |

| 3.2 | Evaluating the participation in two scenarios and in the example from your own practice then posting to the forum discussion. | 45 |

| 3.3 | Citizens’ assembly – exploring pedagogies of deliberation. | 20 |

1 What do we mean by participation in educational settings?

Reflection

Reflection

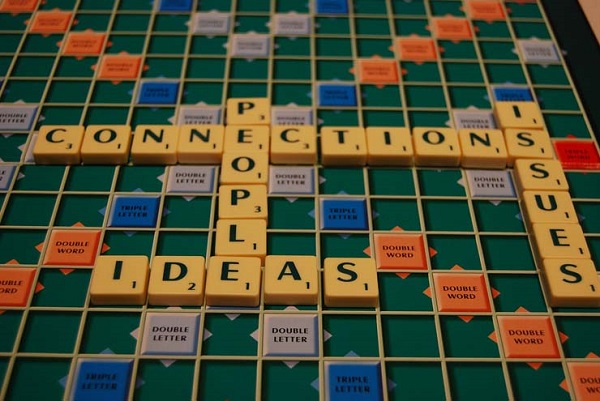

What does ‘participation’ mean to you as a learner and as an educator?

What does participation mean to you?

| What does participation mean to you as a learner? | What does participation mean to you as an educator? |

|---|---|

![]() You can also do this reflective task in your learning journal or with a pen and paper. Write the word ‘participation’ in the middle of a page and use two different coloured pens to write down and collect your thoughts.

You can also do this reflective task in your learning journal or with a pen and paper. Write the word ‘participation’ in the middle of a page and use two different coloured pens to write down and collect your thoughts.

Look for commonalities and differences between the two. Use the image to help you consider the different perspectives.

In your reflections as a learner, you may have considered words and phrases like:

- having a voice

- democracy

- working with others

- feeling heard.

As an educator, you may have included:

- engagement/taking part

- community

- motivation.

You may have also had some crossover between the two points of view, for things like:

- agency in learning

- feedback.

In this section you’ll explore many of these areas and how they relate to participation, remembering it is important to consider the value of participation, not only from your view as the educator – guided as that will be towards your aims, values and understandings – but also from the view of the learners.

The concept of participation has a long history within education, straddling different theoretical and research traditions (Carpentier et al., 2019). From a sociological position the word participation is focused on ‘taking part’ as an active process of learning. Here the emphasis is on individuals contributing, where knowledge is ‘made’ through processes of (mainly verbal) interactions (Piaget, 1971; Vygotsky, 1978). This has led to a rise in learner-centred group work, where being actively in discussion with others is a valued form of participation to deepen understanding.

Another strand of participation in education arises from ancient Greek philosophies of democracy, emphasising education’s role in developing learners into public as well as private citizens (Carpentier et al., 2019). In this democratic view of participation, the focus is on agency, representation and power sharing, and has strongly influenced the rise of citizenship education (Davies and Chong, 2016) and the ‘rights’ agenda (UNICEF, 1989).

This plurality of meanings and intentions can be seen in the debates around participation as a sustainable pedagogy. However, as noted by Rautio et al. (2022), across all forms of participation in education some ‘hidden’ questions need to be surfaced which are particularly important when thinking about sustainable pedagogies:

- Participation for whose benefit?

- Participation on whose terms?

To which we could also add:

- Participation as pedagogical processes of what?

- Participation in/across/between what spaces?

Central to these questions are issues of:

- Whether participation (particularly in education settings) is used as a technicist ‘tool’ to meet expected and planned for outcomes (where it could lead to a homogenisation of views or experiences, with a focus on individualised outcomes or learning, and where dominating positions are restated).

- How far participatory pedagogies can lead to authentic difference making, change, or transformative practices?

- In simplified terms, does participation lead to more of the same for our environment and society, or something actively different?

2 For whose benefit? The case for participatory sustainable pedagogies

Participation as the co-construction of learning and for the development of democratically active citizens are both critical reasons why participation is central to sustainable pedagogies. However, a shift is needed in thinking about who benefits from such participation. Much of educational practice is focused on individualism – individual achievement, individual progress, individual cognitive understanding. This is strongly reinforced by the systems and processes that most educators work within, and therefore to think beyond these structures is challenging.

However, education as sustainability, where our concerns lie with the current and future challenges our learners will face, requires us to actively challenge this individualistic view. A key pillar of sustainable education is to connect, collaborate, share, and empathise, not only with other humans (individuals, communities and beyond), but with environments, material worlds, and non-human partners with whom humans live in symbiosis (Haraway, 2016).

Many authors within and beyond sustainability education, have drawn on ideas of indigenous participation in and with the world, where they conceptualise participation as more-than individual. In this way, participating is very local, contextual to the situation, and entangled with our environments and materials as much as it is with other humans. Mueller (in Kelly, 2022, p. 3) describes a:

quality of participation with Earth that is necessary for any community, if they wish to endure within the storied unfolding of the fully animate, living planet

while Kelly (2022, p. 3) describes how such an engagement changes us because:

it constructs a different world within which we live. We live fused to the land in a vital way. If we want to create a different future, we need to live a different present, so that the present can... create different futurities.

These ideas will be picked up again in more depth in Unit 7.

This view of participation shifts the emphasis from benefits that are individual to benefits of participation which reach and spread well beyond the human/non-human, nature/culture, and I/them binaries that are so prevalent in our educational systems and societies.

2.1 Case study: Art for Action

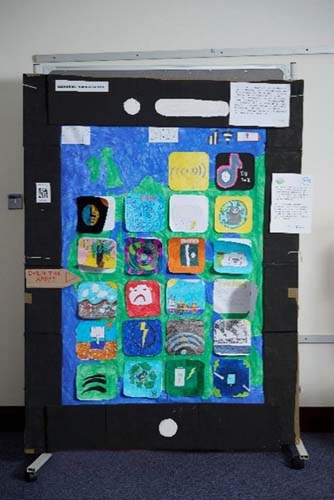

This project, run by Highland One World Global Learning Centre (2022), invited primary schools to create art projects relating to the Sustainable Development Goals. Their artwork was displayed at the Highland Council headquarters for two weeks while COP27 was taking place in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt.

The project had three stages – Learn, Think, and Get Creative:

- Learn asked groups to identify a climate issue that mattered to them, using the SDGs and UNCRC as a starting point. Groups then researched the issue to find out more.

- Think then asked groups to identify the change they wanted to see (locally or globally) on this issue.

- Get Creative invited the groups to create a piece of eye-catching artwork to communicate the change they wanted to see, as well as make a very short video to introduce themselves and the piece.

The artwork was not only about co-producing something (in a sociological sense) but it also raised important questions about young people's ability and opportunity to participate in and with their local environments and communities (in a democratic sense). It raised questions around young people’s:

- assumptions about and relationships with their immediate environments

- understanding of connections between local and global issues

- ability and opportunity to influence local and national policymakers

- ability to inspire change through visual art and storytelling

- ability to use found and repurposed materials for positive ends

- role in their local community as change-makers.

The feedback from the primary schools who took part was overwhelmingly positive, with many schools talking about the sense of accomplishment and pride that pupils felt in producing the pieces of art (Table 1). The pupils felt connected and a part of their community, feeling that they had played an important role in inspiring change.

Table 1 Pieces of artwork

| This piece used recycled pieces of rubbish to create an underwater scene. The piece focuses on SDG 14 – Life below water and uses a catchy slogan to grab people’s attention – be fantastic, recycle your plastic! |

| This piece uses a repeating bottle shape to give voice to nature and underwater life that has been affected by human-caused climate change, and damage by plastics in the ocean. |

| This piece creates an eye-catching and interactive piece to explore issues relating to the environmental and human impact of the lifecycle of technology, particularly smart phones. |

Activity 3.1 Participation for community (people, environment, policy) benefit

Future-making through participation requires more than received knowledge and working towards pre-planned outcomes set by the educator. It requires a shift towards forward-thinking, imaginative, experimental, and playful approaches to pedagogy. This is discussed more in Unit 4: Transdisciplinarity, but below is an optional activity focused on the role of imagination and hope.

Explore

Explore

Read Pheobe Tickell’s blog about Imagination Activism.

Consider how imagination features in your own practices? How does allowing imagination space in pedagogy promote a different type of participation?

- Imagination Activism – by Phoebe Tickell (substack.com)

3 Participation on whose terms?

Participation is a way to encourage learners to understand ideas such as the importance of collaboration and the understanding that can develop through working and problem solving together. Participation as a pedagogy therefore requires more than token gestures.

Next, study the two case study scenarios.

3.1 Case study: Growing wild

A local council decide to plant some wildflowers in spaces around a primary school perimeter as part of their sustainability plan. The council approach the school asking if they want to be involved. Below are two different scenarios of what happened next.

Scenario 1

The school agreed that this was an important local initiative and that the children should take part. They were the ones who would see the flowers grow – it was for their community. On day two people from the council arrived at the school with the equipment and classes of children were taken out to the edge of the playing field where the turf had already been lifted. Each child got to dig some topsoil into the plot with a spade and each got a pinch of seed mix to scatter. As they planted, they discussed the benefits for the insects and the fact that these seeds would grow in the school playground.

A photograph was taken of the children sowing seeds and digging the soil for the school website and for the local paper. One of the members of staff took responsibility for keeping an overview of the plantings and instructing the school caretaker if any weeding or watering seemed needed. They invited the local newspaper in when the flowers were in full bloom and pictures were again taken with the children who were asked to say what they liked best about the project.

Scenario 2

After the council had contacted the school, the sustainability lead teacher asked them what had already been decided and how far the children could get involved in the planning. The council were open to ideas to make this initiative as impactful as possible and therefore the teacher decided to explain the initiative in an assembly and ask each class to think about four key issues:

- location

- what flowers/plants would be best for that location

- what benefits will the planting bring

- how the community would look after the planting over time.

As a result of class discussions, research projects developed into soil types, flower and plant needs, insect needs, and location microclimates. Across the classes children invited in the local farmer, seed merchant, environmental officer and community council representative – all of whom were parents of children in the school.

The teacher, through the school council then supported the children to create a presentation to the council as to what they thought would be best – which included a suggestion to have a small pinch of seeds for all residents with gardens backing onto the playing fields to create an insect ‘superhighway’ of flowers between the school and the local woodland and stream. When the planting happened, not all children were directly involved, but afterwards, each class took turns monitoring and looking after the new planting. They invited local residents to an information evening which the school council led, involving the community in ongoing discussions about other planting and environmental care opportunities.

These scenarios are deliberately provocative asking you to think about ‘participation on whose terms’. There are always moments where much more could be done with an opportunity, but time, resources and relationships are more limited in making that happen. However, these examples do bring to light different notions of what it means to participate as you’ll explore in the next activity.

Activity 3.2 Inclusive participation

1. ![]() Read the following descriptions of how participation can occur – which descriptions would you match up with each of the two scenarios you have read above?

Read the following descriptions of how participation can occur – which descriptions would you match up with each of the two scenarios you have read above?

Table 2 How participation occurs

| Initiation of participation | More like scenario 1 or 2? | |

|---|---|---|

| Induced | More powerful people or organisations encourage or make people participate in ways that they have deemed appropriate or helpful. | |

| Invited | An invitation may come from a more powerful group of people or organisation, but it is an opening to participate on terms set out together. | |

| Autonomous/organic | Participation arises from mutual concern or action. | |

| Outcomes of participation | More like scenario 1 or 2? | |

| Visible/audible | Explicitly statable or performable, usually through words, writings, images, sound or video. | |

| Actionable | Can be seen through changes to the environment, or to behaviours, attitudes or values. | |

| Silent | More difficult to articulate through words or images but can be ‘felt’ through more embodied/emotional states such as ‘sense of belonging’, ‘connection’, ‘community’, ‘witnessing’, ‘empathising’. | |

3. ![]() Think about your example of participation that you would like to or have incorporated in your practice which you made notes about for Activity 3.1 Question 3.

Think about your example of participation that you would like to or have incorporated in your practice which you made notes about for Activity 3.1 Question 3.

4. ![]() How would you analyse your own event or sequence of participation using the descriptors above? Would you now make changes to that activity?

How would you analyse your own event or sequence of participation using the descriptors above? Would you now make changes to that activity?

Post a summary of about 100 words to the Activity 3.2 forum discussion.

4 Participation as pedagogies of…?

This unit has highlighted how participation in education can be built on assumptions of individualism in education, challenging educators to think about who benefits, and who defines the terms of participating. To address this in-built individualism requires us to shift our attention to pedagogies that meaningfully entangle ourselves and others with the world.

In Section 4.1–4.3 we will explore three such approaches.

4.1 Relating to space, place and community

Participation with others and within a local community can act as a powerful method to not only increase feelings of belonging but also as a catalyst for change-making. However, it is easy for people to feel disconnected from these types of activities without an invitation to take part. Deliberate invitations to act together with others and with a local space, place or environment can enhance and develop the ties and entanglement between participants and that space.

In building sustainable lives, this entanglement can deepen the ‘participatory stakes’ individuals and communities feel towards their local space, place or environment and crucially, to the environments of others too. Finding meaningful ways for education to reach out beyond the institution and reach into relationships with others (people and environments) requires explicit knowledge of local communities and spaces. You may well feel you have these connections, but not be fully realising them for sustainable purposes.

Reflection

Reflection

Reflect on the connections you currently make between your practices and local communities, spaces, environments, and organisations.

How can you utilise these connections further to build stronger pedagogies of relationships? How can you strengthen your existing knowledge and relationships of the communities and contexts in which you practice?

4.2 Curating

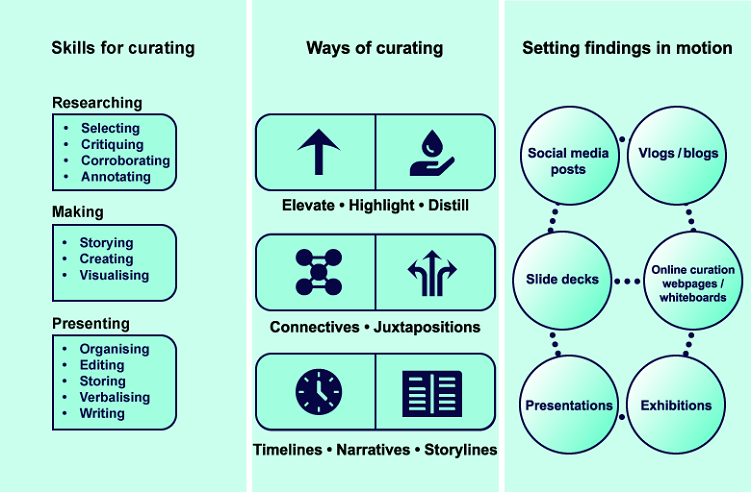

The word curate means ‘to care for’. Care was alluded to in Unit 1, where notions of solidarity, compassion, ethics, and empathy surfaced in relation to UNESCO’s (2023) Renewing the Social Contract for Education. Curating as a process of participatory care is a pedagogical approach that can be adapted to any discipline, problem, issue, or concept. It is shared here not as a technique to be applied, but as an approach to thinking about the nature of participation as:

- generative

- connective

- organic

- multimodal

allowing for silent, hidden as well as visible, explicit participation. It can create connectivities across time and space, as well as create spaces of critique and integration of learning with self, with community, environments and others.

The internet has led to a dramatic expansion of the participatory sphere (Cornwall and Coelho, 2006), where individuals can participate in local, national and global actions. It has reduced barriers between citizens and policy, far away environments and locally created issues, and between generations and cultures. This allows our learners to curate materials, perspectives and issues from across the globe in minutes.

Reflection

Reflection

Using the image in Figure 1, consider how far pedagogies of curation are relevant to and are, or have potential to be, explicitly explored in your own practices?

4.3 Deliberating

In his article on climate crisis as a driver for pedagogical renewal in higher education, McCowan (2023, p. 944) argues for pedagogies of deliberation, as a forum for ‘Listening to the views of others, communicating our own views, and through the interaction of the two, revising those views’ as an essential participatory process in tackling complex, unpredictable problems. There are many examples of deliberative pedagogies, most notably the ‘flipped classroom’, but there is also a rise in larger scale, mass citizen deliberative approaches which can offer a different perspective on what deliberative pedagogies could look like.

The idea of citizens’ assemblies is gathering pace in politics around the world, with recent examples being the establishment of a permanent people’s assembly as part of Paris’s governance, Ireland’s assemblies on abortion, Scotland’s assembly on climate and recently, the RSPB with other partner organisation created the ‘People’s Assembly for Nature’. These examples are often held up as a form of rapid, just, democracy in action, but are often highly pedagogic, developing greater understandings of issues. They also create opportunities to synthesise different evidence and to think about individual and collective action that can be taken as a result.

Activity 3.3 Processes of participation

![]() Watch the following two videos:

Watch the following two videos:

Explore

Explore

Explore more about citizens assemblies by spending some time exploring this website for key messages and resources that may help you establish the idea of citizens’ assemblies within your practice or context.

5 Embracing the precarity of participation

Participation can be a difficult proposition, particularly in educational settings where the story many of our learners have, is of individual understanding and achievement. Within this story, participating with others can feel like an inefficient or distracting way to reach that individualistic end.

There is not the space here to discuss how we shift this story and help learners see the interconnected importance of their learning with others and their environments. However, it does need recognising that, in order to participate our learners, and we as their educators, need some particular attitudes, approaches, and skills. Further, it is worth acknowledging that these may feel counter-intuitive to the dominant historic educational assumptions we have sometimes been encultured into.

One such assumption is the control of knowledge and information by educators. As McCowan argues in his article about the need for pedagogical renewal in higher education (2023), it is vital to ‘let go’ (p. 945), allowing knowing (both cognitive and embodied) to move differently and unexpectedly in response to learner-led, educator-involved, critical deliberation and debate. Such pedagogical movements can be considered more akin to rhizomatic, improvisatory, pathways through learning, rather than a pre-planned educator-led movement towards fixed learning outcomes.

Reflection

Reflection

How does it feel to ‘let go’ and let students improvise their own learning pathways, modes of response and criteria for success?

What do you feel are the risks and how can these be mitigated?

Can you think of a space in your own teaching where you can experiment more with handing over and embracing the precarity of exploratory and playful learning in your curriculum area?

6 Summary of Unit 3

In this unit you have explored the sustainable pedagogy of participation and considered what participation is, who it benefits (and on whose terms), as well as considering the ways that participation invites us to embed ourselves in the places, communities and nature around us. You have also thought about how we participate and the characteristics of successful participation.

Through the activities you have taken part in during this unit, you should feel that you have developed some awareness of how to critique and develop your own participatory practices. You now know to consider how your practices enhance not only your learners’ experience and outcomes but your own too, in pursuit of embedding ideas around sustainability into your teaching.

Participation in its many forms can provide an extremely rewarding and productive way to engage learners with a subject area and provides a range of benefits, not only for the learners and educators, but for the wider community and world around us.

The next unit explores ideas relating to partnership as a sustainable pedagogy and follows on from many of the ideas raised in this unit. Participation naturally works hand in hand with partnership, as has been alluded to in the case studies and scenarios in this unit.

Unit 3 cards

Click/tap each card to reveal the text.

Continue to Unit 4: Towards new futures – a role for partnership.

Further reading

Involve (2024) Methods – Citizens’ Assembly. Available at: https://involve.org.uk/ resource/ citizens-assembly (Accessed: 29 February 2024).

Tickell, P. (2022) ‘Introducing a new kind of activist: The Imagination Activist’, IMoral Imagination [Blog]. Available at: https://moralimaginations.substack.com/ p/ imagination-activism (Accessed: 29 February 2024).

References

Carpentier, N., Duarte Melo, A., Ribeiro, F. (2019) ‘Rescuing participation: a critique on the dark participation concept’, Open Edition Journals, 36, pp. 17–35. Available at: https://journals.openedition.org/ cs/ 1284 (Accessed: 4 March 2024).

Cornwall, A. and Coelho, V. S. (2006) Spaces for Change? The Politics of Citizen Participation in New Democratic Arenas. London: Zed.

Davies, I. and Chong, E.K.M. (2016) ‘Current challenges for citizenship education in England’,Asian Education and Development Studies, 5(1), pp. 20–36. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1108/ AEDS-05-2015-0015 (Accessed: 11 October 2023).

Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. New York, NY: Duke University Press.

Highland One World Global Learning Centre (2022) Art for Action. Available at: https://highlandoneworld.org.uk/ projects/ cop-27-art-for-action/ (Accessed: 25 October 2023).

Kelly, V. (2022) ‘Resonance as an Act of Attunement Through Sensing, Being, and Belonging: Returning to the Teachings’, p. 3–19, in Haggstrom, M., and Schmidt, C. (eds) Relational and Critical Perspectives on Education for Sustainable Development: Belonging and Sensing in a Vanishing World. Switzerland: Springer.

McCowan, T. (2023) ‘The climate crisis as a driver for pedagogical renewal in higher education’, Teaching in Higher Education, 28(5), pp. 933–952. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1080/ 13562517.2023.2197113 (Accessed: 11 October 2023).

Piaget, J. (1971) ‘The theory of stages in cognitive development’, in D. R. Green, M. P. Ford, and G. B. Flamer, Measurement and Piaget. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Rautio, P., Tammi, T., Aivelo, T., Hohti, R., Kervinen, A., Saari, M (2022) ‘“For whom? By whom?”: critical perspectives of participation in ecological citizen science’, Cultural Studies of Science Education, 17, pp. 765–793. Available at: https://link.springer.com/ article/ 10.1007/ s11422-021-10099-9 (Accessed: 11 October 2023).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

UNICEF UK (1989) The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available at: https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/ wp-content/ uploads/ 2010/ 05/ UNCRC_PRESS200910web.pdf?_ga=2.78590034.795419542.1582474737-1972578648.1582474737 (Accessed: October 11 2023).