Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 6:36 PM

Unit 5: Transdisciplinarity

Introduction

Welcome to Unit 5 of Sustainable pedagogies.

In this unit, you will see how transdisciplinarity can be considered central to sustainable pedagogies. Transdisciplinarity requires a different way of thinking about how most knowledge and skills are divided into disciplines. These disciplines can be in danger of acting as silos if considered strictly bounded. Working across those traditional disciplines can add a great deal to the skills and understanding that students (and indeed all learners) develop.

Transdisciplinarity works with the other sustainable pedagogies discussed in the course to establish a learning environment where students can explore the knowledge, understanding and skills needed to live sustainably in the world.

At the end of this unit, there will be a short quiz on the ideas you have studied in Units 1–5.

You will need to score 80% or more on this quiz as well as posting to at least one forum discussion in Units 1–7 and one of the two assessed forum discussions in Unit 8, in order to be awarded a digital badge for this course.

Next go to Unit 5 learning outcomes.

Unit 5 learning outcomes

By the end of this unit you will have:

- Explained what transdisciplinarity is and what it means in educational practice.

- Understood how transdisciplinary approaches can develop students’ attunement to, and playful exploration towards new understandings of their world.

- Articulated the importance of creating and making as part of transdisciplinary sustainable pedagogies.

Activity planner

| Activity | Task | Timing (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | Thinking with your own experiences of disciplinary/inter/transdisciplinary being. Adding words to word cloud. | 30 |

| 5.2 | Re-experiencing the familiar and applying this to your context. Post on forum discussion. | 60 |

| 5.3 | Thinking with themes. Making a mind map. | 60 |

1 What do we mean by transdisciplinarity?

Transdisciplinarity is increasingly becoming a focus of research and educational practices. There is a growing recognition that distinct disciplines, as the gatekeepers of specific concepts, ways of knowing, and materials, can act in ways that limit our abilities to think about complex ‘wicked problems’ (introduced in the previous unit) that we face together in the world (UNESCO, 2021). This is not to say that disciplinary knowledge is not important. Transdisciplinary thinking does not exclude or refuse the existence of disciplinary thinking, but instead offers the option of a way of thinking beyond and across these boundaries.

Russell et al. (2008, p. 470) state that transdisciplinarity is a practice that requires a particular pedagogical stance towards knowledge creation and learners’ roles that is ‘problem-oriented, responsive, and open to external knowledge producers, contextualised and systems-based, adaptable, consultative and socially robust’.

At its most basic, transdisciplinarity can be seen as the most integrated form of interdisciplinarity, as mentioned in Table 1, below. Table 1 details Jo Bailey’s (2019) mnemonic – I Can Make It Tasty – which can be used for understanding and remembering the different types of disciplinarities.

Table 1 Jo Bailey’s ‘recipe book of disciplinarities’ – I Can Make It Tasty

Intradisciplinary I (single ingredient)

|  | Intradisciplinary working is within one discipline. Like a single ingredient, clearly distinguishable…

|

|---|---|---|

Crossdisciplinary Can (container of ingredients)

|  | Crossdisciplinary working views one discipline from the frame of reference of another. It’s like lots of different ingredients on a plate, but without chopping them up and mixing them…

|

Multidisciplinary Make (mixed up salad)

|

| Multidisciplinary working brings disciplines together so they can learn from each other, drawing on the mix of disciplinary knowledge. It’s like a salad: the original ingredients are intact, but the flavours begin to blend…

|

Interdisciplinary It (intermingled stew)

|  | Interdisciplinary working starts to take a new form, integrating knowledge and methods from different disciplines and synthesising into a new whole. It’s like a stew: the original ingredients are still partly distinguishable, but the overall is a blended pot of mixed flavours…

|

Transdisciplinary Tasty (totally blended cake)

|  | Transdisiplinary working produces a new, novel form or way of working beyond the original disciplinary boundaries. It’s like a cake: you can no longer see the form of the ingredients as they have taken on a different shape and flavour.

|

Explore

Explore

![]() Watch Jo Bailey explaining her images in:

Watch Jo Bailey explaining her images in:

As Table 1 illustrates, the fundamental difference between transdisciplinarity and other forms of bringing disciplines together is the entangled ‘making’ with, across and/or between disciplines which leads to something – knowledge, understanding, experiences, artifacts. Within each creation the contribution of any particular disciplinary field is fundamentally indistinguishable. What is made is something different and new – it is a modulation beyond what is currently known, experienced or expected. Engaging in such transdisciplinary making is therefore a process of expanding and developing different ways of being, acting or seeing.

As Rigolot (2020, p. 1) states, ‘When transdisciplinarity is considered as a way of being, it is inseparable from personal life and extends far beyond the professional activities of a researcher’. This extends conceptualisations of transdisciplinarity as a practice (Russell et al., 2008).

Activity 5.1 Your own experiences of disciplinary or transdisciplinary being

2. ![]() Add your thoughts to the word cloud under your subject discipline or area.

Add your thoughts to the word cloud under your subject discipline or area.

Thinking with the cake metaphor; by making, mixing, combining and layering – note the active nature of these terms – you can begin to allow:

- Disciplinary concepts, languages, and images to be set in motion – taking on different meanings and possibilities as they are de-territorialised and experienced in different ways.

- For pluriversality (multi-vocal, multi-affect, multi-critique) which shifts us away from notions of a universal epistemology with its application and generalisation across all contexts.

- For methodologies to evolve and develop with the emerging activity.

- Recognition of the central role of materiality, digital entanglements and bodies as transdisciplinary ‘modes’ of knowing.

These will be explored further in the next section in which you will look at why these features of transdisciplinarity are important for sustainable pedagogies.

2 Transdisciplinarity: an imperative for sustainable pedagogies

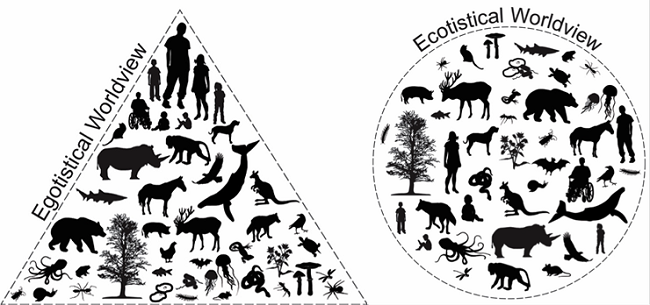

Learners, as indeed all of us as citizens, face an increasingly dynamic world where complex phenomena – whether, environmental, technological, or economic – interact and change in ways that we cannot predict. In many ways, this has been true for all of humanity’s existence so it’s nothing new, but the challenges we face this time cannot be overcome by only using human power and control over materials, processes and relationships – stemming from Enlightenment views of man and knowledge (Duigan, 2023).

Instead, humans will need to adjust their thinking about what it means to learn from a human-dominant, cognitive-based, transference of accepted knowledge, to one of transdisciplinary, improvisatory, response-able (that is able to be responded to) acts of learning to live with and in our world – locally, nationally and globally.

This shift from power over others (whether human or non-human) to power with others requires a shift of stance towards learning (Berger, 2005). This shift towards a pre-defined, pre-planned outcome involves learners, not as receivers of knowledge and educators not as transmitters, gatekeepers or facilitators only. The word ‘only’ is important here because this is not saying that educational practices cannot have an aim, and that defined learning cannot take place, but that we also need pedagogies of:

attunement and attentionality

following and exploring

de-territorialising and redefining.

These ideas for pedagogies are explored in the following sections. By developing competencies to attune, pay attention, follow and explore, de-territorialise and redefine, your students and yourself will be equipped to be more resilient in living within the complex and dynamic world. All of these competencies are underpinned by pedagogies of making or creating something new or different. Making enables us to collectively take action and to do something to feel we have actually contributed.

Explore

Explore

Explore transdisciplinarity by reading ‘The Transdisciplinary Moment(um)’ article by Julie Thompson Klein (2013). The article promotes five-word clusters around the meanings of transdisciplinarity.

In your learning journal, note down between 5–10 of the terms that capture your attention as ones you think could help you think about your practices. Spend a few minutes imagining activities, approaches or experiences that would exemplify these types of pedagogies.

Consider the arguments being made:

- Is there anything that particularly challenges your current practices?

- Is there anything that excites or intrigues you to explore further?

3 Attunement and attentionality

Attuning to the interconnectivity of ourselves, our learning and our environments is not only to think cognitively, but to pay attention with all of our senses (Cooke et al., 2023). This will allow ideas, connections, relationships and new knowings to emerge and be responded to.

Masschelein (2010) argues that such attentionality is not aimed at arriving at a particular perspective or vision (as could be considered in situations where educators have a pre-planned outcome and exert power over what learning occurs), but to open ourselves to the world. This challenges us to be present in ‘such a way that the present can present itself to me’ (p. 48), and in which we allow our gaze to be ‘liberated’ so that we can see differently. Masschelein describes the act of such attentionality as involving a ‘suspension of judgement… a kind of waiting’ (p. 48), to really attend to what is occurring.

This attention and attunement is important to transdisciplinarity as it allows us and our learners to reposition ourselves towards objects or concepts of inquiry – seeing, feeling, and exploring them anew. This is a significant political act – shifting attention and attunement to things beyond storied understandings within a given discipline. For example, tuning in and attending to terms such as ‘cell’ or ‘pattern’ or ‘connectivity’ across disciplinary frameworks opens up new possibilities for understandings.

This process of attunement involves paying attention to more than the linguistic, more than the text, more than the screen, more than the mono-disciplinary view but involves our whole ‘body-minds’ (Dewey, 1929, p. 232). We can think, feel and enact understandings of these terms (and many others) through many modes beyond words. This refocusing and reconnecting body, mind, concept and object asks learners to attend, not only to the future gains of their study but to the final result and the here and now, and also to the troubles that are currently being faced and the generative opportunities that arise.

Activity 5.2 The power of paying attention

Use the videos below to help you re-experience the familiar.

1a. ![]() Watch Videos 1–3 below from Kay McCrann’s blog.

Watch Videos 1–3 below from Kay McCrann’s blog.

2. ![]() Now think about a disciplinary concept that you teach, or if you teach across disciplines, an area you feel you would like to explore (which could relate to your responses to Activity 5.1).

Now think about a disciplinary concept that you teach, or if you teach across disciplines, an area you feel you would like to explore (which could relate to your responses to Activity 5.1).

For your chosen concept or area, think about how your learners, with their access to the environments, materials, resources they have, could (re)experience the concept, area or issues through an embodied experience that helps them attune and attend to the learning in a way they otherwise would not. Examples could be:

- The physical concept of diffraction – experienced by paddling in a river.

- The mathematics of pattern and geometry and symmetry – experienced through close attention (including touching) their natural occurrences in plants in a garden or shells on a beach.

- The educational and psychological concepts of behaviours – experienced and attuned to through considering animal, family, work, community behaviours across different activities and settings.

- An author's description of a woodland camp – experienced and attuned to by walking, touching, smelling and then creating own writings while in amongst trees.

The notion of echo, reverb and silence in music and physics – experienced through playing with sound in different interior spaces to ‘feel’ the sound movements respond to different material designs.

Consider how you would set up the activity for your students.

3. ![]() Summarise your thoughts on devising your activity in about 200 words and post your summary to the Activity 5.2 forum discussion.

Summarise your thoughts on devising your activity in about 200 words and post your summary to the Activity 5.2 forum discussion.

4 Following and exploring

Sometimes when we are following someone else’s lead we pay less attention to what is happening along the way, as we try to keep up and value the same things as the person we are following. In this way the person leading is navigating us as the learners through to the end point. Sometimes the intentionality of the pre-determined endpoint can limit awareness and attunement to what is experienced and pedagogically important along the way. Ingold compares such navigation to negotiating a maze, arguing that:

We may still get lost in them [a maze], but that loss is experienced not as a discovery on the way to nowhere but as a setback in the achievement of a predetermined goal. We mean to get from here to there and are frustrated by wrong turns and culs-de-sac.

In contrast to the maze, Ingold argues we should consider education as wayfaring – that the journey is regarded as life, not just the getting there. In this view, instead of inducting learners into our navigation, where they experience and value only the importance of reaching our determined destination, we allow space and time for ‘ex-duction (drawing out) of the learner into the world itself’ (2015, p. 135). In this way, the learner is given the task of finding their way, exploring, experimenting, playfully observing and responding. This is much more akin to the co-creation of ‘desire lines’; paths that are made by individuals to reflect the places they want to walk, as shown in Figure 2.

Reflection

Reflection

Reflect on creating the educational conditions for student ‘desire lines’ and consider your recent teaching.

1. How far do you think you create the conditions for learners to find their way, explore, experiment, play, observe and respond to their own desire lines within the learning?

2. What are the challenges of this approach?

3. What would need to change to enable this type of learning to occur?

Such wayfaring, by its very nature, can become transdisciplinary. When learners become less tied to the disciplinary boundaries, languages, concepts and processes, they are set free to work out what would be the most applicable approach for any given situation, which may move them beyond disciplinary constraints. As noted by UNESCO, this involves considering the very meaning and nature of what it means to learn.

Constructing a new social contract means exploring how established ways of thinking about education, knowledge and learning inhibit us from opening new paths and moving towards the futures we desire. Merely expanding the current educational development model is not a viable route forward. Our difficulties are not only the result of limited resources and means. Our challenges also stem from why and how we educate and the ways we organize learning.

UNESCO summarise their proposal for renewing education in the box below.

Proposals for renewing education

Pedagogy should be organized around the principles of cooperation, collaboration, and solidarity. It should foster the intellectual, social and moral capacities of students to work together and transform the world with empathy and compassion. There is unlearning to be done too, of bias, prejudice, and divisiveness. Assessment should reflect these pedagogical goals in ways that promote meaningful growth and learning for all students.

Curricula should emphasize ecological, intercultural and interdisciplinary learning that supports students to access and produce knowledge while also developing their capacity to critique and apply it. Curricula must embrace an ecological understanding of humanity that rebalances the way we relate to Earth as a living planet and our singular home. The spread of misinformation should be countered through scientific, digital and humanistic literacies that develop the ability to distinguish falsehoods from truth. In educational content, methods and policy we should promote active citizenship and democratic participation.

Reflection

Reflection

Enacting a renewed education.

1. How would you apply the UNESCO proposals to a recent activity for learners you prepared/delivered/experienced?

2. What are the main challenges you can identify?

Explore

Explore

Reimagine learning using the following Thousand Shades of India (TSOI) case study.

![]() Watch the ‘Learning Reimagined’ video up to 12 minutes and note how it meets the UNESCO proposals.

Watch the ‘Learning Reimagined’ video up to 12 minutes and note how it meets the UNESCO proposals.

‘Learning Reimagined! − TSOI Documentary (Project Defy)’

5 Redefining and de-territorialising

Transdisciplinarity, as depicted in the cake analogy at the start of this unit (Table 1), invites us to not just bring together different disciplines, but to make or create something entirely different across or between them, which is connected directly to our lived experiences and the world. To do so unsettles, redefines and de-territorialises not only disciplinary language but also embodied disciplinary habits – in other words, it sets words and bodies into different motions.

Burnard et al. mention that de-territorialisation does not have to be:

a destructive shift away from our disciplinary knowledges and experiences, but a constructive remaking, a re-territorializing, to find new experiences, words, and relationships, which all provided generative ways to democratically and creatively re-view our practices of teaching.

Activity 5.3 Thinking with themes

Transdisciplinary experiences often arise from concepts, spaces or topics that have immediate transdisciplinary opportunities.

1a. ![]() From the list below, choose one theme and create a mind map in your learning journal in response to the statement above. (You can also write one out on a separate piece of paper or use a digital tool like mindmup, if you wish.) Note all the associations, concepts, ideas, spaces and activities you can think of related to it.

From the list below, choose one theme and create a mind map in your learning journal in response to the statement above. (You can also write one out on a separate piece of paper or use a digital tool like mindmup, if you wish.) Note all the associations, concepts, ideas, spaces and activities you can think of related to it.

- Sense of place

- Nature phenomena

- Relationships

- Beauty

- Body systems

- Performance

- Force and motion

- Pattern

- Trade

- Memories

- Natural materials

- Expression

- Identity

- Work

- Growth

2. ![]() Now read Sharon Witt and Helen Clarke’s (2020) article on ways young people can be invited to pay attention to more-than-human perspectives. In doing so, the pupils (in this case primary school children) redefine and de-territorialise their current position to understand and relate to the trees in a richer, deeper way than they otherwise would have.

Now read Sharon Witt and Helen Clarke’s (2020) article on ways young people can be invited to pay attention to more-than-human perspectives. In doing so, the pupils (in this case primary school children) redefine and de-territorialise their current position to understand and relate to the trees in a richer, deeper way than they otherwise would have.

As you read, consider how you could enact similar ‘Invitations of place’ and ‘Coming to know the world’ activities in your practice.

- Witt, S. and Clarke, H. (2020) ‘Paying attention to a more-than-human world’

6 Summary of Unit 5

Transdisciplinarity makes something different or new, through its unique entanglement of people, disciplines, materials, languages and environments. Therefore, this process of making as an act of doing learning is central. The making process then becomes part of the wayfaring. It could be making a small endeavour of playful experimentation to encourage thinking differently to be a substantial part of the outcome, or it could be making an artifact from a project or experience. Such making can act as a catalyst for connecting transdisciplinary learning to communities or environments, or it could remain something to think with individually or collectively as learning continues to develop and extend outwards.

In this unit you have explored what transdisciplinarity means, how it can be enacted, and the challenges it poses to existing forms of education. Essentially, outcomes of a transdisciplinary approach are not defined by individual disciplines but result in something that is entirely new. The environmental challenges currently faced by humanity require a shift from power over others to power with others, and developing resilience to live within our ever-changing world can be supported by this sustainable pedagogy.

When learners are attuned to and pay attention to the world using all of their senses, a sensitivity and drive for action can emerge as a result of the new awareness, understanding and way of travelling through the world. Instead of following the well-worn route to the acquisition of knowledge and understanding, learners need to be given the time and space to explore and experiment. In doing this, ties to specific disciplines are lessened and a complete change in our understanding as to what it means to learn can result. Continuing with the current approach to education, knowledge and learning can hinder such valuable exploration, along with the potential for the transformation that is driven by active citizenship.

In bringing together different disciplines to make something new, there is a redefinition and constructive approach to exploring and understanding our actions. As transdisciplinarity results in making something new this can take on many different forms, all of which have the capacity to promote further learning, both individually and collectively. Understanding and using transdisciplinarity is central to sustainable pedagogies and offers a vital element to support the development of the competencies learners need to prosper in an uncertain future.

Unit 5 cards

Click/tap each card to reveal the text.

Continue to the next section where you'll find the course quiz..

Quiz

Now it's time to complete the course quiz, which assesses the ideas you have studied in Units 1 to 5. There are 10 questions of varying question types to test your knowledge and understanding of the materials.

To pass the quiz, you must achieve at least 80%. However, if you don't, you can always try again as many times as you like.

Remember, to pass the entire course, you will need to pass the quiz, and also post in one of the discussions in the Units 1 to 7 forum and the forum in Unit 8.

When you've completed the quiz, you can continue to Unit 6: Learning in transition − perspectives and practices

Further reading

Bailey, J. (2021) Making cakes: transdisciplinary terms and teams, 19 June [YouTube]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=KnVWoymu4kI&ab_channel=JoBailey (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Ecoversities (2022) Learning Reimagined! A TSOI documentary, 7 November [YouTube]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=iTh7G8K_bZ0&ab_channel=ThousandShadesofIndia (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Thompson Klein, J. (2013) ‘The Transdisciplinary Moment(um)’, Integral Review, 9(2), pp. 189–199. Available at: https://www.integral-review.org/ documents/ old/ Klein,Transdisciplinary-Moment(um),Vol.9,No.2.pdf (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

References

Bailey, J. (2019) ‘Disciplinary recipes: a visual guide [Blog]. Available at: https://makinggood.design/ thoughts/ tasty/ (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Berger, B. K. (2005) ‘Power over, power with, and power to relations: Critical reflections on public relations, the dominant coalition, and activism’, Journal of Public Relations Research, 17(1), pp. 5–28.

Burnard, P., Colucci-Gray, L. and Cooke, C. (2022) ‘Transdisciplinarity: Re-Visioning How Sciences and Arts Together Can Enact Democratizing Creative Educational Experiences’, Review of Research in Education, 46(1), pp. 166–197.

Cooke, C., Colucci-Gray, L. and Burnard, P. (2023) ‘Sensing bodies: Transdisciplinary enactments of ‘thing-power’ and ‘making-with’ for educational future-making’, Digital Culture and Education, 14(5). Available at: https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/ en/ publications/ sensing-bodies-transdisciplinary-enactments-of-thing-power-and-ma (Accessed: 11 March 2023).

Dewey, J. (1929) The quest for certainty: A study of the relation of knowledge and action, New York: Putnam.

Duigan, B. (2023) Enlightenment: European History, Britannica Online. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/ event/ Enlightenment-European-history (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Ingold, T. (2013) Making, Growing, Learning: Two lectures presented at UFMG, Belo Horizonte, October 2011. Educação Em Revista, 29(3), pp. 301–323.

Ingold, T. (2015) The Life of Lines, Oxfordshire, Routledge.

Lupinacci, J. (2017) ‘Addressing 21st Century Challenges in Education: An Ecocritical Conceptual Framework toward an Ecotistical Leadership in Education’, Impacting Education: Journal on Transforming Professional Practice, 2, pp. 20–27.

McCrann, K (2023) ‘Minibeasts, Mark-making and me: Contemporary embodied drawing approaches to multispecies worlds’ [Blog]. Available at: https://kaymccrann.com/ (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Masschelein, J (2010) ‘E-ducating the gaze: the idea of a poor pedagogy’, Ethics and Education, 5(1), pp. 43–53.

Rigolot, C. (2020) ‘Transdisciplinarity as a discipline and a way of being: complementarities and creative tensions’, Humanities and Social Science Communications, 7. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1057/ s41599-020-00598-5 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Russell, W., Wickson, F., and Carew, A.L. (2008) ‘Transdisciplinarity: Context, Contradictions and Capacity’, Futures, 40(5), pp. 460–472. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/ j.futures.2007.10.005 (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Thompson Klein, J. (2013) ‘The Transdisciplinary Moment(um)’, Integral Review, 9(2), pp. 189–199.

UNESCO (2021) Reimagining our futures together: a new social contract for education. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ ark:/ 48223/ pf0000379707.locale=en (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Witt, S. and Clarke, H. (2020) ‘Paying attention to a more-than-human world’ in Hammond, L., Biddulph, M., Catling, S., McKendrick, J. H. (eds) Children, Education and Geography – Rethinking Intersections. London: Routledge, pp. 215–232.