Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 25 February 2026, 2:30 AM

Labour and Delivery Care Module: 8. Abnormal Presentations and Multiple Pregnancies

Study Session 8 Abnormal Presentations and Multiple Pregnancies

Introduction

In previous study sessions of this module, you have been introduced to the definitions, signs, symptoms and stages of normal labour, and about the ‘normal’ vertex presentation of the fetus during delivery. In this study session, you will learn about the most common abnormal presentations (breech, shoulder, face or brow), their diagnostic criteria and the required actions you need to take to prevent complications developing during labour. Taking prompt action may save the life of the mother and her baby if the delivery becomes obstructed because the baby is in an abnormal presentation. We will also tell you about twin births and the complications that may result if the two babies become ‘locked’ together, preventing either of them from being born.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 8

After studying this session, you should be able to:

8.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 8.1 and 8.2)

8.2 Describe how you would identify a fetus in the vertex presentation and distinguish this from common malpresentations and malpositions. (SAQs 8.1 and 8.2)

8.3 Describe the causes and complications for the fetus and the mother of fetal malpresentation during full term labour. (SAQ 8.3)

8.4 Describe how you would identify a multiple pregnancy and the complications that may arise. (SAQ 8.4)

8.5 Explain when and how you would refer a woman in labour due to abnormal fetal presentation or multiple pregnancy. (SAQ 8.4)

8.1 Normal and abnormal presentations

8.1.1 Vertex presentation

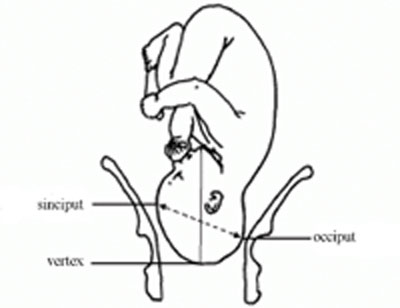

In about 95% of deliveries, the part of the fetus which arrives first at the mother’s pelvic brim is the highest part of the fetal head, which is called the vertex (Figure 8.1). This presentation is called the vertex presentation. Notice that the baby’s chin is tucked down towards its chest, so that the vertex is the leading part entering the mother’s pelvis. The baby’s head is said to be ‘well-flexed’ in this position.

During early pregnancy, the baby is the other way up — with its bottom pointing down towards the mother’s cervix — which is called the breech presentation. This is because during its early development, the head of the fetus is bigger than its buttocks; so in the majority of cases, the head occupies the widest cavity, i.e. the fundus (rounded top) of the uterus. As the fetus grows larger, the buttocks become bigger than the head and the baby spontaneously reverses its position, so its buttocks occupy the fundus. In short, in early pregnancy, the majority of fetuses are in the breech presentation and later in pregnancy most of them make a spontaneous transition to the vertex presentation.

8.1.2 Malpresentations

You will learn about obstructed labour in Study Session 9.

When the baby presents itself in the mother’s pelvis in any position other than the vertex presentation, this is termed an abnormal presentation, or malpresentation. The reason for referring to this as ‘abnormal’ is because it is associated with a much higher risk of obstruction and other birth complications than the vertex presentation. The most common types of malpresentation are termed breech, shoulder, face or brow. We will discuss each of these in turn later. Notice that the baby can be ‘head-down’ but in an abnormal presentation, as in face or brow presentations, when the baby’s face or forehead (brow) is the presenting part.

8.1.3 Malposition

Although it may not be so easy for you to identify this, the baby can also be in an abnormal position even when it is in the vertex presentation. In a normal delivery, when the baby’s head has engaged in the mother’s pelvis, the back of the baby’s skull (the occiput) points towards the front of the mother’s pelvis (the pubic symphysis), where the two pubic bones are fused together. This orientation of the fetal skull is called the occipito-anterior position (Figure 8.2a). If the occiput (back) of the fetal skull is towards the mother’s back, this occipito-posterior position (Figure 8.2b) is a vertex malposition, because it is more difficult for the baby to be born in this orientation. The good thing is that more than 90% of babies in vertex malpositions undergo rotation to the occipito-anterior position and are delivered normally.

You learned the directional positions: anterior/in front of and posterior/behind or in the back of, in the Antenatal Care Module, Part 1, Study Session 3.

Note that the fetal skull can also be tilted to the left or to the right in either the occipito-anterior or occipito-posterior positions.

8.2 Causes and consequences of malpresentations and malpositions

In the majority of individual cases it may not be possible to identify what caused the baby to be in an abnormal presentation or position during delivery. However, the general conditions that are thought to increase the risk of malpresentation or malposition are listed below:

Multiple pregnancy is the subject of Section 8.7 of this study session. You learned about placenta previa in the Antenatal Care Module, Study Session 21.

- Abnormally increased or decreased amount of amniotic fluid

- A tumour (abnormal tissue growth) in the uterus preventing the spontaneous inversion of the fetus from breech to vertex presentation during late pregnancy

- Abnormal shape of the pelvis

- Laxity (slackness) of muscular layer in the walls of the uterus

- Multiple pregnancy (more than one baby in the uterus)

- Placenta previa (placenta partly or completely covering the cervical opening).

If the baby presents at the dilating cervix in an abnormal presentation or malposition, it will more difficult (and may be impossible) for it to complete the seven cardinal movements that you learned about in Study Sessions 3 and 5. As a result, birth is more difficult and there is an increased risk of complications, including:

You learned about PROM in Study Session 17 of the Antenatal Care Module, Part 2.

- Premature rupture of the fetal membranes (PROM)

- Premature labour

- Slow, erratic, short-lived contractions

- Uncoordinated and extremely painful contractions, with slow or no progress of labour

- Prolonged and obstructed labour, leading to a ruptured uterus (see Study Sessions 9 and 10 of this Module)

- Postpartum haemorrhage (see Study Session 11)

- Fetal and maternal distress, which may lead to the death of the baby and/or the mother.

With these complications in mind, we now turn your attention to the commonest types of malpresentation and how to recognise them.

8.3 Breech presentation

In a breech presentation, the fetus lies with its buttocks in the lower part of the uterus, and its buttocks and/or the feet are the presenting parts during delivery. Breech presentation occurs on average in 3–4% of deliveries after 34 weeks of pregnancy.

When is the breech position the normal position for the fetus?

During early pregnancy the baby’s bottom points down towards the mother’s cervix, and its head (the largest part of the fetus at this stage of development) occupies the fundus (rounded top) of the uterus, which is the widest part of the uterine cavity.

8.3.1 Causes of breech presentation

You can see a transverse lie in Figure 8.7 later in this study session.

In the majority of cases there is no obvious reason why the fetus should present by the breech at full term. In practice, what is commonly observed is the association of breech presentation at delivery with a transverse lie earlier in the pregnancy, i.e. the fetus lies sideways across the mother’s abdomen, facing a sideways implanted placenta. It is thought that when the placenta is in front of the baby’s face, it may obstruct the normal process of inversion, when the baby turns head-down as it gets bigger during the pregnancy. As a result, the fetus turns in the other direction and ends in the breech presentation. Some other circumstances that are thought to favour a breech presentation during labour include:

- Premature labour, beginning before the baby undergoes spontanous inversion from breech to vertex presentation

- Multiple pregnancy, preventing the normal inversion of one or both babies

- Polyhydramnios: excessive amount of amniotic fluid, which makes it more difficult for the fetal head to ‘engage’ with the mother’s cervix (polyhydramnios is pronounced ‘poll-ee-hy-dram-nee-oss’. Hydrocephaly is pronounced ‘hy-droh-keff-all-ee’)

- Hydrocephaly (‘water on the brain’) i.e. an abnormally large fetal head due to excessive accumulation of fluid around the brain

- Placenta praevia

- Breech delivery in the previous pregnancy

- Abnormal formation of the uterus.

8.3.2 Diagnosis of breech presentation

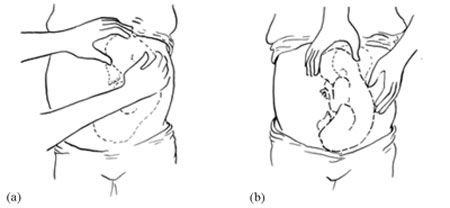

On abdominal palpation the fetal head is found above the mother’s umbilicus as a hard, smooth, rounded mass, which gently ‘ballots’ (can be rocked) between your hands.

Why do you think a mass that ‘ballots’ high up in the abdomen is a sign of breech presentation? (You learned about this in Study Session 11 of the Antenatal Care Module.)

The baby’s head can ‘rock’ a little bit because of the flexibility of the baby’s neck, so if there is a rounded, ballotable mass above the mother’s umbilicus it is very likely to be the baby’s head. If the baby was ‘bottom-up’ (vertex presentation) the whole of its back will move of you try to rock the fetal parts at the fundus (Figure 8.3).

Once the fetus has engaged and labour has begun, the breech baby’s buttocks can be felt as soft and irregular on vaginal examination. They feel very different to the relatively hard rounded mass of the fetal skull in a vertex presentation. When the fetal membranes rupture, the buttocks and/or feet can be felt more clearly. The baby’s anus may be felt and fresh thick, dark meconium may be seen on your examining finger. If the baby’s legs are extended, you may be able to feel the external genitalia and even tell the sex of the baby before it is born.

8.3.3 Types of breech presentation

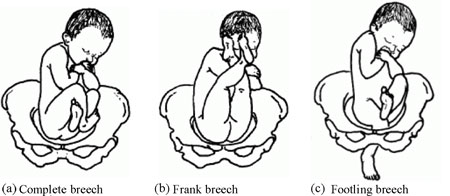

There are three types of breech presentation, as illustrated in Figure 8.4. They are:

- Complete breech is characterised by flexion of the legs at both hips and knee joints, so the legs are bent underneath the baby.

- Frank breech is the commonest type of breech presentation, and is characterised by flexion at the hip joints and extension at the knee joints, so both the baby’s legs point straight upwards.

- Footling breech is when one or both legs are extended at the hip and knee joint and the baby presents ‘foot first’.

8.3.4 Risks of breech presentation

![]() Refer all cases of breech presentation to the nearest higher-level health facility.

Refer all cases of breech presentation to the nearest higher-level health facility.

Regardless of the type of breech presentation, there are significant associated risks to the baby. They include:

- The fetal head gets stuck (arrested) before delivery

- Labour becomes obstructed when the fetus is disproportionately large for the size of the maternal pelvis

- Cord prolapse may occur, i.e. the umbilical cord is pushed out ahead of the baby and may get compressed against the wall of the cervix or vagina

- Premature separation of the placenta (placental abruption)

- Birth injury to the baby, e.g. fracture of the arms or legs, nerve damage, trauma to the internal organs, spinal cord damage, etc.

A breech birth may also result in trauma to the mother’s birth canal or external genitalia through being overstretched by the poorly fitting fetal parts.

Cord prolapse in a normal (vertex) presentation was illustrated in Study Session 17 of the Antenatal Care Module, and placental abruption was covered in Study Session 21.

What will be the effect on the baby if it gets stuck, the labour is obstructed, the cord prolapses, or placental abruption occurs?

The result will be hypoxia, i.e. it will be deprived of oxygen, and may suffer permanent brain damage or die.

You learned about the causes and consequences of hypoxia in the Antenatal Care Module.

8.4 Face presentation

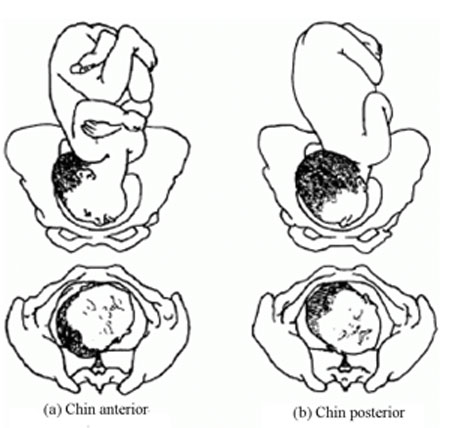

Face presentation occurs when the baby’s neck is so completely extended (bent backwards) that the occiput at the back of the fetal skull touches the baby’s own spine (see Figure 8.5). In this position, the baby’s face will present to you during delivery.

Refer the mother if a baby in the chin posterior face presentation does not rotate and the labour is prolonged.

The incidence of face presentation is about 1 in 500 pregnancies in full term labours. In Figure 8.5, you can see how flexed the head is at the neck. Babies who present in the ‘chin posterior’ position (on the right in Figure 8.5) usually rotate spontaneously during labour, and assume the ‘chin anterior’ position, which makes it easier for them to be born. However, they are unlikely to be delivered vaginally if they fail to undergo spontaneous rotation to the chin anterior position, because the baby’s chin usually gets stuck against the mother’s sacrum (the bony prominence at the back of her pelvis). A baby in this position will have to be delivered by caesarean surgery.

8.4.1 Causes of face presentation

The causes of face presentation are similar to those already described for breech births:

- Laxity (slackness) of the uterus after many previous full-term pregnancies

- Multiple pregnancy

- Polyhydramnios (excessive amniotic fluid)

- Congenital abnormality of the fetus (e.g. anencephaly, which means no or incomplete skull bones)

- Abnormal shape of the mother’s pelvis.

8.4.2 Diagnosis of face presentation

Face presentation may not be easily detected by abdominal palpation, especially if the chin is in the posterior position. On abdominal examination, you may feel irregular shapes, formed because the fetal spine is curved in an ‘S’ shape. However, on vaginal examination, you can detect face presentation because:

- The presenting part will be high, soft and irregular.

- When the cervix is sufficiently dilated, you may be able to feel parts of the face, such as the orbital ridges above the eyes, the nose or mouth, gums, or bony chin.

- If the membranes are ruptured, the baby may suck your examining finger!

But as labour progresses, the baby’s face becomes oedematous (swollen with fluid), making it more difficult to distinguish from the soft shape you will feel in a breech presentation.

8.4.3 Complications of face presentation

Complications for the fetus include:

- Obstructed labour and ruptured uterus

- Cord prolapse

- Facial bruising

- Cerebral haemorrhage (bleeding inside the fetal skull).

8.5 Brow presentation

In brow presentation, the baby’s head is only partially extended at the neck (compare this with face presentation), so its brow (forehead) is the presenting part (Figure 8.6). This presentation is rare, with an incidence of 1 in 1000 deliveries at full term.

8.5.1 Possible causes of brow presentation

You have seen all of these factors before, as causes of other malpresentations:

- Lax uterus due to repeated full term pregnancy

- Multiple pregnancy

- Polyhydramnios

- Abnormal shape of the mother’s pelvis.

8.5.2 Diagnosis of brow presentation

Brow presentation is not usually detected before the onset of labour, except by very experienced birth attendants. On abdominal examination, the head is high in the mother’s abdomen, appears unduly large and does not descend into the pelvis, despite good uterine contractions. On vaginal examination, the presenting part is high and may be difficult to reach. You may be able to feel the root of the nose, eyes, but not the mouth, tip of the nose or chin. You may also feel the anterior fontanel, but a large caput (swelling) towards the front of the fetal skull may mask this landmark if the woman has been in labour for some hours.

Recall the appearance of a normal caput over the posterior fontanel shown in Figure 4.4 earlier in this Module.

8.5.3 Complications of brow presentation

The complications of brow presentation are much the same as for other malpresentations:

- Obstructed labour and ruptured uterus

- Cord prolapse

- Facial bruising

- Cerebral haemorrhage.

Which are you more likely to encounter — face or brow presentations?

Face presentation, which occurs in 1 in 500 full term labours. Brow presentation is more rare, at 1 in 1,000 full term labours.

8.6 Shoulder presentation

Shoulder presentation is rare at full term, but may occur when the fetus lies transversely across the uterus (Figure 8.7), if it stopped part-way through spontaneous inversion from breech to vertex, or it may lie transversely from early pregnancy. If the baby lies facing upwards, its back may be the presenting part; if facing downwards its hand may emerge through the cervix. A baby in the transverse position cannot be born through the vagina and the labour will be obstructed. Refer babies in shoulder presentation urgently.

![]() Do not attempt to turn a sideways lying baby. Unless a trained physician or midwife can turn the baby ‘head down’, it must be delivered by caesarean surgery.

Do not attempt to turn a sideways lying baby. Unless a trained physician or midwife can turn the baby ‘head down’, it must be delivered by caesarean surgery.

8.6.1 Causes of shoulder presentation

Causes of shoulder presentation could be maternal or fetal factors.

Maternal factors include:

- Lax abdominal and uterine muscles: most often after several previous pregnancies

- Uterine abnormality

- Contracted (abnormally narrow) pelvis.

Fetal factors include:

- Preterm labour

- Multiple pregnancy

- Polyhydramnios

- Placenta previa.

What do ‘placenta previa’ and ‘polyhydramnios’ indicate?

Placenta previa is when the placenta is partly or completely covering the cervical opening. Polyhydramnios is an excess of amniotic fluid. They are both potential causes of malpresentation.

8.6.2 Diagnosis of shoulder presentation

On abdominal palpation, the uterus appears broader and the height of the fundus is less than expected for the period of gestation, because the fundus is not occupied by either the baby’s head or buttocks. You can usually feel the head on one side of the mother’s abdomen. On vaginal examination, in early labour, the presenting part may not be felt, but when the labour is well progressed, you may feel the baby’s ribs. When the shoulder enters the pelvic brim, the baby’s arm may prolapse and become visible outside the vagina.

8.6.3 Complications of shoulder presentation

Complications include:

- Cord prolapse

- Trauma to a prolapsed arm

- Obstructed labour and ruptured uterus

- Fetal hypoxia and death.

Remember that a shoulder presentation means the baby cannot be born through the vagina; if you detect it in a woman who is already in labour, refer her urgently to a higher health facility.

![]() In all cases of malpresentation or malposition, do not attempt to turn the baby with your hands! Only a specially trained doctor or midwife should attempt this. Refer the mother so she and her baby can get emergency obstetric care.

In all cases of malpresentation or malposition, do not attempt to turn the baby with your hands! Only a specially trained doctor or midwife should attempt this. Refer the mother so she and her baby can get emergency obstetric care.

8.7 Multiple pregnancy

In this section, we turn to the subject of multiple pregnancy, when there is more than one fetus in the uterus. More than 95% of multiple pregnancies are twins (two fetuses), but there can also be triplets (three fetuses), quadruplets (four fetuses), quintuplets (five fetuses), and other higher order multiples with a declining chance of occurrence. The spontaneous occurrence of twins varies by country: it is lowest in East Asian countries like Japan and China (1 out of 1000 pregnancies are fraternal or non-identical twins), and highest in black Africans, particularly in Nigeria, where 1 in 20 pregnancies are fraternal twins. In general, compared to single babies, multiple pregnancies are highly associated with early pregnancy loss and high perinatal mortality, mainly due to prematurity.

8.7.1 Types of twin pregnancy

Twins may be identical (monozygotic) or non-identical and fraternal (dizigotic). Monozygotic twins develop from a single fertilised ovum (the zygote), so they are always the same sex and they share the same placenta. By contrast, dizygotic twins develop from two different zygotes, so they can have the same or different sex, and they have separate placentas. Figure 8.8 shows the types of twin pregnancy and the processes by which they are formed.

8.7.2 Diagnosis of twin pregnancy

On abdominal examination you may notice that:

- The size of the uterus is larger than the expected for the period for gestation.

- The uterus looks round and broad, and fetal movement may be seen over a large area. (The shape of the uterus at term in a singleton pregnancy in the vertex presentation appears heart-shaped rounder at the top and narrower at the bottom.)

- Two heads can be felt.

- Two fetal heart beats may be heard if two people listen at the same time, and they can detect at least 10 beats different (Figure 8.6).

- Ultrasound examination can make an absolute diagnosis of twin pregnancy.

8.7.3 Consequences of twin pregnancy

Women who are pregnant with twins are more prone to suffer with the minor disorders of pregnancy, like morning sickness, nausea and heartburn. Twin pregnancy is one cause of hyperemesis gravidarum (persistent, severe nausea and vomiting). Mothers of twins are also more at risk of developing iron and folate-deficiency anaemia during pregnancy.

Can you suggest why anaemia is a greater risk in multiple pregnancies?

The mother has to supply the nutrients to feed two (or more) babies; if she is not getting enough iron and folate in her diet, or through supplements, she will become anaemic.

Other complications include the following:

- Pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders like pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are more common in twin pregnancies.

- Pressure symptoms may occur in late pregnancy due to the increased weight and size of the uterus.

- Labour often occurs spontaneously before term, with premature delivery or premature rupture of membranes (PROM).

- Respiratory deficit (shortness of breath, because of fast growing uterus) is another common problem.

Twin babies may be small in comparison to their gestational age and more prone to the complications associated with low birth weight (increased vulnerability to infection, losing heat, difficulty breastfeeding).

You will learn about low birth weight babies in detail in the Postnatal Care Module.

- Malpresentation is more common in twin pregnancies, and they may also be ‘locked’ at the neck with one twin in the vertex presentation and the other in breech. The risks associated with malpresentations already described also apply: prolapsed cord, poor uterine contraction, prolonged or obstructed labour, postpartum haemorrhage, and fetal hypoxia and death.

- Conjoined twins (fused twins, joined at the head, chest, or abdomen, or through the back) may also rarely occur.

8.8 Management of women with malpresentation or multiple pregnancy

As you have seen in this study session, any presentation other than vertex has its own dangers for the mother and baby. For this reason, all women who develop abnormal presentation or multiple pregnancy should ideally have skilled care by senior health professionals in a health facility where there is a comprehensive emergency obstetric service. Early detection and referral of a woman in any of these situations can save her life and that of her baby.

What can you do to reduce the risks arising from malpresentation or multiple pregnancy in women in your care?

During focused antenatal care of the pregnant women in your community, at every visit after 36 weeks of gestation you should check for the presence of abnormal fetal presentation. If you detect abnormal presentation or multiple pregnancy, you should refer the woman before the onset of labour.

Summary of Study Session 8

In Study Session 8, you learned that:

- During early pregnancy, babies are naturally in the breech position, but in 95% of cases they spontaneously reverse into the vertex presentation before labour begins.

- Malpresentation or malposition of the fetus at full term increases the risk of obstructed labour and other birth complications.

- Common causes of malpresentations/malpositions include: excess amniotic fluid, abnormal shape and size of the pelvis; uterine tumour; placenta praevia; slackness of uterine muscles (after many previous pregnancies); or multiple pregnancy.

- Common complications include: premature rupture of membranes, premature labour, prolonged/obstructed labour; ruptured uterus; postpartum haemorrhage; fetal and maternal distress which may lead to death.

- Vertex malposition is when the fetal head is in the occipito-posterior position — i.e. the back of the fetal skull is towards the mother’s back instead of pointing towards the front of the mother’s pelvis. 90% of vertex malpositions rotate and deliver normally.

- Breech presentation (complete, frank or footling) is when the baby’s buttocks present during labour. It occurs in 3–4% of labours after 34 weeks of pregnancy and may lead to obstructed labour, cord prolapse, hypoxia, premature separation of the placenta, birth injury to the baby or to the birth canal.

- Face presentation is when the fetal head is bent so far backwards that the face presents during labour. It occurs in about 1 in 500 full term labours. ‘Chin posterior’ face presentations usually rotate spontaneously to the ‘chin anterior’ position and deliver normally. If rotation does not occur, a caesarean delivery is likely to be necessary.

- Brow presentation is when the baby’s forehead is the presenting part. It occurs in about 1 in 1000 full term labours and is difficult to detect before the onset of labour. Caesarean delivery is likely to be necessary.

- Shoulder presentation occurs when the fetal lie during labour is transverse. Once labour is well progressed, vaginal examination may feel the baby’s ribs, and an arm may sometimes prolapse. Caesarean delivery is always required unless a doctor or midwife can turn the baby head-down.

- Multiple pregnancies are always at high risk of malpresentation. Mothers need greater antenatal care, and twins are more prone to complications associated with low birth weight and prematurity.

- Any presentation other than vertex after 34 weeks of gestation is considered as high risk to the mother and to her baby. Do not attempt to turn a malpresenting or malpositioned baby! Refer the mother for emergency obstetric care.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 8

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 8.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.1, 8.2 and 8.4)

Which of the following definitions are true and which are false? Write down the correct definition for any which you think are false.

A Fundus — the ‘rounded top’ and widest cavity of the uterus.

B Complete breech — where the legs are bent at both hips and knee joints and are folded underneath the baby.

C Frank breech — where the breech is so difficult to treat that you have to be very frank and open with the mother about the difficulties she will face in the birth.

D Footling breech — when one or both legs are extended so that the baby presents ‘foot first’.

E Hypoxia — the baby gets too much oxygen.

F Multiple pregnancy — when a mother has had many babies previously.

G Monozygotic twins — develop from a single fertilised ovum (the zygote). They can be different sexes but they share the same placenta.

H Dizygotic twins — develop from two zygotes. They have separate placentas, and can be of the same sex or different sexes.

Answer

A is true. The fundus is the ‘rounded top’ and widest cavity of the uterus.

B is true. Complete breech is where the legs are bent at both hips and knee joints and are folded underneath the baby.

C is false. A frank breech is the most common type of breech presentation and is when the baby’s legs point straight upwards (see Figure 8.4).

D is true. A footling breech is when one or both legs are extended so that the baby presents ‘foot first’.

E is false. Hypoxia is when the baby is deprived of oxygen and risks permanent brain damage or death.

F is false. Multiple pregnancy is when there is more than one fetus in the uterus.

G is false. Monozygotic twins develop from a single fertilised ovum (the zygote), and they are always the same sex, as well as sharing the same placenta.

H is true. Dizygotic twins develop from two zygotes, have separate placentas, and can be of the same or different sexes.

SAQ 8.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.1 and 8.2)

What are the main differences between normal and abnormal fetal presentations? Use the correct medical terms in bold in your explanation.

Answer

In a normal presentation, the vertex (the highest part of the fetal head) arrives first at the mother’s pelvic brim, with the occiput (the back of the baby’s skull) pointing towards the front of the mother’s pelvis (the pubic symphysis).

Abnormal presentations are when there is either a vertex malposition (the occiput of the fetal skull points towards the mother’s back instead towards of the pubic symphysis), or a malpresentation (when anything other than the vertex is presenting): e.g. breech presentation (buttocks first); face presentation (face first); brow presentation (forehead first); and shoulder presentation (transverse fetal).

SAQ 8.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.3 and 8.5)

- a.List the common complications of malpresentations or malposition of the fetus at full term.

- b.What action should you take if you identify that the fetus is presenting abnormally and labour has not yet begun?

- c.What should you not attempt to do?

Answer

- a.The common complications of malpresentation or malposition of the fetus at full term include: premature rupture of membranes, premature labour, prolonged/obstructed labour; ruptured uterus; postpartum haemorrhage; fetal and maternal distress which may lead to death.

- b.You should refer the mother to a higher health facility – she may need emergency obstetric care.

- c.You should not attempt to turn the baby by hand. This should only be attempted by a specially trained doctor or midwife and should only be done at a health facility.

SAQ 8.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.4 and 8.5)

A pregnant woman moves into your village who is already at 37 weeks gestation. You haven’t seen her before. She tells you that she gave birth to twins three years ago and wants to know if she is having twins again this time.

- a.How would you check this?

- b.If you diagnose twins, what would you do to reduce the risks during labour and delivery?

Answer

- a.How to check if this pregnancy is twins:

- Is the uterus larger than expected for the period of gestation?

- What is its shape – is it round (indicative of twins) or heart-shaped (as in a singleton pregnancy)?

- Can you feel more than one head?

- Can you hear two fetal heartbeats (two people listening at the same time) with at least 10 beats difference?

- If there is access to a higher health facility, and you are still not sure, try and get the woman to it for an ultrasound scan.

- b.How do you reduce the risks during delivery of twins:

- Be extra careful to check that the mother is not anaemic.

- Encourage her to rest and put her feet up to reduce the risk of increased blood pressure or swelling in her legs and feet.

- Be alert to the increased risk of pre-eclampsia.

- Expect her to go into labour before term, and be ready to get her to the health facility before she goes into labour, going with her if at all possible.

- Get in early touch with that health facility to warn them to expect a referral from you.

- Make sure that transport is ready to take her to a health facility when needed.