Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:28 AM

TI-AIE: Speaking and listening

What this unit is about

This unit focuses on how meaningful speaking and listening opportunities contribute to effective classroom teaching and learning.

You will plan and evaluate several activities to develop your students’ speaking and listening skills. You will also consider the ways in which listening in on your students can inform your assessment of their learning and the planning of your future lessons.

What you can learn in this unit

- The value of productive student talk in the classroom.

- How to use pictures as the basis of speaking and listening activities.

- How to use student talk as a means of evaluating their understanding and progress, so that you can modify your teaching plans accordingly.

Why this approach is important

Talking and listening are central to teaching and learning in all curriculum areas. Talk is also the foundation of literacy. Young children listen and speak well before they read or write. They learn that they can use speech to express their needs and wishes, find out about things, and engage in imaginative, exploratory play. Children need opportunities to listen to and speak about different topics in a range of contexts in order to develop their language skills, which will also enhance their school achievement.

1 Talking and learning

In traditional classrooms, talk is often dominated by the teacher. However, the students’ attitudes to learning – together with their learning gains – improve noticeably when, through their own talk, they are actively involved in the learning process.

Pause for thought

|

Learning involves adding to and gaining new perspectives on one’s existing knowledge, skills and experiences. Talk plays a key role in this process because it helps students to articulate their thoughts, reveal what is not clear to them, ask questions, explore new ideas and learn from their exchanges with their teacher and their classmates.

In this first activity, you will think about the value of talk for learning.

Activity 1: Talk for learning

Do this activity with a colleague if possible.

First, read Resource 1, ‘Talk for learning’. When you have finished, carefully re-read the following two excerpts:

- Even young students with limited literacy and numeracy skills can demonstrate higher order thinking skills if the task is designed to build on their prior experience and is enjoyable. For example, students can make predictions about a story, an animal or a shape from photos, drawings or real objects. Students can list suggestions and possible solutions about problems to a puppet or character in a role play.

Plan the lesson around what you want the students to learn and think about, as well as what type of talk you want students to develop.

Pause for thought Resource 1 suggests that students can make predictions about story, an animal or a shape from photos, drawings or real objects, and that students can make suggestions and possible solutions about problems to a puppet or a character in a role play.

Consider the questions: ‘What could happen next?’, ‘Have we seen this before?’, ‘What could this be?’ and ‘Why do you think that is?’

Now think back to your recent lessons. Can you identify any times when your students did exploratory talk? Which subjects or topics did this kind of talk relate to? |

Talk for learning is valuable for students of all ages. The more opportunities that students are given to talk in a purposeful way, the more skilful they will become in talking and listening thoughtfully.

2 Using pictures as a prompt for student talk

Read Case Study 1, which describes how a Class I teacher uses pictures to encourage her students to talk about what they know.

Case Study 1: Using pictures to stimulate classroom talk

Ms Priyanka is a Class I teacher in a rural school in Uttar Pradesh. Here she talks of how she employs images of familiar scenes as prompts for classroom talk.

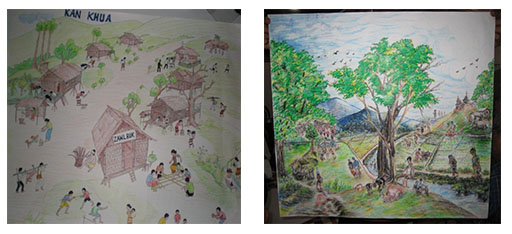

I use pictures [see Figure 1] to encourage my students to talk. The pictures, by local artists, are printed on large sheets of durable paper and coated in plastic. The title of the first picture is ‘My Village’ and the title of the second one is ‘Agriculture’.

First I put the pictures up on the wall. I don’t mention them, but let my students notice and examine them in their own time. Over the next day or two I observe my students talking to one another about the pictures and discussing the details in them.

I then organise a 20-minute session to discuss the two pictures with a group of students each day. Sometimes I take the group outside to do this. I set the rest of the class other quiet work to do at the same time.

I list a number of questions in advance. Some questions are intended to elicit simple descriptions, while others are intended to prompt more exploratory talk, in the form of reasoning, predicting and relating things to the students’ own experience. Here are some examples of each type.

- What is this a picture of?

- Can you describe what you see in the picture?

- What are the people doing?

- Have you ever played these games? Can you explain how to play them?

- Have you ever helped your family in the jum fields?

- What is your favourite food from the fields? How do you prepare that food?

- What part of the picture do you like best? Why exactly?

I listen to each student carefully without correcting or interrupting them. I insist that the other students listen carefully too. By encouraging my students to talk about what they see and know, I learn a lot about them. This helps me to assess their ability and consider ways of supporting or extending them further.

A few of my students are too shy to speak, but they are clearly listening to their classmates. I try to ask them simple questions that allow them to respond with a single word, a nod or a shake of their head to indicate that they understand me.

I always attempt to give my students good models of speaking and listening. I talk clearly, make eye contact with those who respond and ask further questions to indicate my interest in their answers.

Pause for thought

|

Your students will probably be from diverse social, cultural and linguistic backgrounds. The speaking and listening activities that you incorporate into your classroom should draw on the varied knowledge that your students bring to school. This is particularly true for students whose home language is different from the school language. Notice how the picture prompts used in Case Study 1 would have been familiar scenes to all of Ms Priyanka’s students. Be aware that students who are silent may still be participating by listening, thinking and learning.

In the following activity you will use pictures to encourage speaking and listening among your students.

Activity 2: A picture-based group discussion

You can use any pictures from your textbook or from other sources in your school or community for this activity.

Using Case Study 1 for ideas, plan a lesson in which you use a picture or a series of pictures to encourage your students to talk about what they see or imagine to be happening, relating it to their knowledge and experience.

Before you plan the lesson, do the following:

- Think about how you will organise the activity. Consider whether it will involve pairs, small groups or the whole class, and whether it will take place indoors or outdoors.

- Brainstorm with a colleague the types of questions you could ask your students.

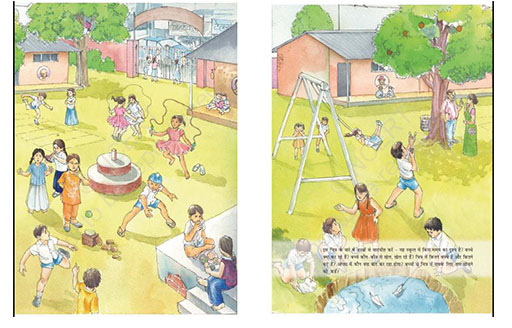

The following questions are based on the pictures in Figure 2. You will need to devise other questions depending on the images you use and the age of the class you are teaching:

- Description questions:

- What do you think is happening in this picture?

- What are the children doing?

- How many girls are there? How many boys? How many adults?

- What colours can you see?

- Reasoning questions:

- Point to some of the adults and ask, ‘Who do you think they are, and what are they saying to each other?’

- Point to some of the children and ask, ‘

- What do you think they are saying?’

- What is the weather or the season? How do you know?

- What time of day do you think it is? Why?

- Is it quiet or noisy? How can you tell?

- Do you think the boy who is eating can see the girls skipping from where he is sitting?

- Are the children sad or happy? How can you tell?

- Why do the girls and boys play different games?

- Does the girl like the loud noise in her ear?

- Prediction questions:

- What will happen when the boy shoots his sling shot?

- Will the boy catch the ball?

- What do you think will happen next?

- Relating the picture to the students’ own experience:

- Does your school compound look like this?

- Do you play these games?

- What games do you like to play?

- What would you like to do if you were in the playground?

Pause for thought Once you have undertaken this activity with your class, answer these questions:

|

Read Resource 2, ‘Using questioning to promote thinking’, to learn more about using questions in your teaching plans and activities.

In the next activity, you will use pictures to encourage your students to make up and tell stories in the classroom.

Activity 3: A story from pictures

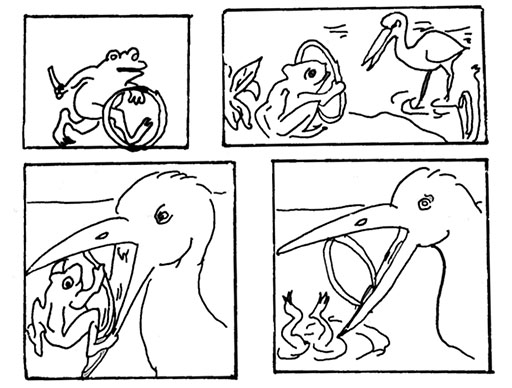

Look at the four pictures in Figure 3. Make up a story that relates to the pictures. It can be as short or as long as you like, and can include dialogue.

Tell your story to a colleague. What did they think of it?

Now try a picture-based storytelling activity with your students. You can use any series of pictures for this purpose – from a book, magazine or newspaper, or drawn by yourself, a friend or a colleague.

Begin by modelling the activity by telling your own short story about the picture sequence in Figure 3. Then arrange your students in pairs or groups and invite them to make up a different story using the same picture prompts. Pair or group students with the same home language together so that they can prepare to tell the story in that language. Encourage them to use different voices and gestures if possible.

When everyone is ready, ask your students to tell their story to another pair or group, or to the whole class. Allow time to discuss the ways the home language stories could be translated into the school language too.

Pause for thought

|

3 Using student talk to inform your teaching

Students often talk about their learning. Now try Activity 4.

Activity 4: Listening in on your students’ talk

To understand the potential of student talk as a learning resource, try to discreetly listen in on a conversation your students are having. Do this more than once if you can.

See if you can overhear your students doing some of the following:

- paying attention to something

- thinking about it carefully

- exchanging observations

- organising their observations and experiences in a systematic way

- challenging one another’s observations and experiences

- arguing on the basis of observation and experience

- making a prediction

- recalling an earlier observation or experience

- imagining someone else’s experience or feelings

- recounting their own feelings or experiences.

Pause for thought

|

As a teacher, it is important to be a good listener. Very often you can incorporate elements of what you hear your students say into your future lesson plans.

Now read the two examples in Case Study 2. As you read, think about how the teachers use what they hear to inform their teaching. When you have finished, find another opportunity to listen in on your students. What aspects of their talk might inform your future classroom activities?

Case Study 2: Building on students’ talk

Ms Bhumi is a Class II teacher in Madhya Pradesh.

I was eating lunch outside when I heard raised voices. I decided not to intervene, but to listen closely. Four students were arguing about a poem I had read to them that morning. While I had been reading the poem, the class had listened quietly. I therefore assumed everyone had understood it. But as I listened to my students arguing, I realised most of them had misunderstood it completely. I learnt this by overhearing their different interpretations of the meaning of some of the key words in the poem.

I decided to revisit the poem with them the next day and explore their understanding of it again. This incident taught me that when we had other text-based lessons, I needed to allow more time to check whether any vocabulary was unfamiliar and explain it carefully if that was the case. I have done this regularly since then and have noticed the benefits already.

Mrs Saroj is a Class V teacher in Bihar.

I used to specify very precisely the points I expected my students to make in their writing assignments. This made their texts very similar.

One morning before class, I heard several students talking together. During those few minutes, they discussed a surprising variety of topics, explaining, questioning, arguing and predicting as they did so. They had so many interesting ideas.

As a result of overhearing them, I realised that if I gave my students opportunities to draw on their spoken language resources, experiences and interests in this way, they would write much more creatively and meaningfully.

Now I organise my students into groups of four or five and give them a topic to discuss before inviting them to do an individual writing assignment. So far, the topics they have talked and written about have included the tea stall outside the school, a local celebration, a recent sports event, and the trees in the neighbourhood. Sometimes I send my students out into the school compound to observe things, discuss them with one another and then write about them.

In the final activity, you will try out a group activity that incorporates talk and writing. You may find the key resource ‘Using groupwork’ useful.

Activity 5: Using group talk to prepare for writing

Using the case study of Mrs Saroj as a guide, prepare a lesson in which you invite your students to discuss a topic before they write about it individually.

- Divide your class into groups of four, five or six.

- Give each group a topic to discuss. This will depend on your students’ age and interests. You could give a photograph or newspaper clipping to each group for inspiration.

- Model with two or three students how you would like them to talk together, demonstrating how to ask helpful exploratory questions and listen respectfully to their classmates’ answers.

- Go around the class, assisting the groups if required. Use this as an opportunity to observe your students’ behaviour, their mastery of language and their understanding of the topic in question.

- After the discussion session, ask your students to write a short essay on the topic they discussed together.

- On occasion, you might wish to distribute your student’s essays among the other members of the group for interest.

- Finally, let your evaluation of your students’ writing inform the planning of your subsequent lessons.

Summary

This unit has provided you with some ideas for creating opportunities for your students to speak and listen to one another to support their classroom learning. It has shown how valuable student discussions can be in providing you with insights into their understanding and progress, in terms of both subject matter and language skills. Such information can contribute to both your classroom practice and your lesson planning. By listening to your students talk, you can plan lessons around what you want them to learn and think about in order to enhance their achievement.

Resources

Resource 1: Talk for learning

Why talk for learning is important

Talk is a part of human development that helps us to think, learn and make sense of the world. People use language as a tool for developing reasoning, knowledge and understanding. Therefore, encouraging students to talk as part of their learning experiences will mean that their educational progress is enhanced. Talking about the ideas being learnt means that:

- those ideas are explored

- reasoning is developed and organised

- as such, students learn more.

In a classroom there are different ways to use student talk, ranging from rote repetition to higher-order discussions.

Traditionally, teacher talk was dominant and was more valued than students’ talk or knowledge. However, using talk for learning involves planning lessons so that students can talk more and learn more in a way that makes connections with their prior experience. It is much more than a question and answer session between the teacher and their students, in that the students’ own language, ideas, reasoning and interests are given more time. Most of us want to talk to someone about a difficult issue or in order to find out something, and teachers can build on this instinct with well-planned activities.

Planning talk for learning activities in the classroom

Planning talking activities is not just for literacy and vocabulary lessons; it is also part of planning mathematics and science work and other topics. It can be planned into whole class, pair or groupwork, outdoor activities, role play-based activities, writing, reading, practical investigations, and creative work.

Even young students with limited literacy and numeracy skills can demonstrate higher-order thinking skills if the task is designed to build on their prior experience and is enjoyable. For example, students can make predictions about a story, an animal or a shape from photos, drawings or real objects. Students can list suggestions and possible solutions about problems to a puppet or character in a role play.

Plan the lesson around what you want the students to learn and think about, as well as what type of talk you want students to develop. Some types of talk are exploratory, for example: ‘What could happen next?’, ‘Have we seen this before?’, ‘What could this be?’ or ‘Why do you think that is?’ Other types of talk are more analytical, for example weighing up ideas, evidence or suggestions.

Try to make it interesting, enjoyable and possible for all students to participate in dialogue. Students need to be comfortable and feel safe in expressing views and exploring ideas without fear of ridicule or being made to feel they are getting it wrong.

Building on students’ talk

Talk for learning gives teachers opportunities to:

- listen to what students say

- appreciate and build on students’ ideas

- encourage the students to take it further.

Not all responses have to be written or formally assessed, because developing ideas through talk is a valuable part of learning. You should use their experiences and ideas as much as possible to make their learning feel relevant. The best student talk is exploratory, which means that the students explore and challenge one another’s ideas so that they can become confident about their responses. Groups talking together should be encouraged not to just accept an answer, whoever gives it. You can model challenging thinking in a whole class setting through your use of probing questions like ‘Why?’, ‘How did you decide that?’ or ‘Can you see any problems with that solution?’ You can walk around the classroom listening to groups of students and extending their thinking by asking such questions.

Your students will be encouraged if their talk, ideas and experiences are valued and appreciated. Praise your students for their behaviour when talking, listening carefully, questioning one another, and learning not to interrupt. Be aware of members of the class who are marginalised and think about how you can ensure that they are included. It may take some time to establish ways of working that allow all students to participate fully.

Encourage students to ask questions themselves

Develop a climate in your classroom where good challenging questions are asked and where students’ ideas are respected and praised. Students will not ask questions if they are afraid of how they will be received or if they think their ideas are not valued. Inviting students to ask the questions encourages them to show curiosity, asks them to think in a different way about their learning and helps you to understand their point of view.

You could plan some regular group or pair work, or perhaps a ‘student question time’ so that students can raise queries or ask for clarification. You could:

- entitle a section of your lesson ‘Hands up if you have a question’

- put a student in the hot-seat and encourage the other students to question that student as if they were a character, e.g. Pythagoras or Mirabai

- play a ‘Tell Me More’ game in pairs or small groups

- give students a question grid with who/what/where/when/why questions to practise basic enquiry

- give the students some data (such as the data available from the World Data Bank, e.g. the percentage of children in full-time education or exclusive breastfeeding rates for different countries), and ask them to think of questions you could ask about this data

- design a question wall listing the students’ questions of the week.

You may be pleasantly surprised at the level of interest and thinking that you see when students are freer to ask and answer questions that come from them. As students learn how to communicate more clearly and accurately, they not only increase their oral and written vocabulary, but they also develop new knowledge and skills.

Resource 2: Using questioning to promote thinking

Teachers question their students all the time; questions mean that teachers can help their students to learn, and learn more. On average, a teacher spends one-third of their time questioning students in one study (Hastings, 2003). Of the questions posed, 60 per cent recalled facts and 20 per cent were procedural (Hattie, 2012), with most answers being either right or wrong. But does simply asking questions that are either right or wrong promote learning?

There are many different types of questions that students can be asked. The responses and outcomes that the teacher wants dictates the type of question that the teacher should utilise. Teachers generally ask students questions in order to:

- guide students toward understanding when a new topic or material is introduced

- push students to do a greater share of their thinking

- remediate an error

- stretch students

- check for understanding.

Questioning is generally used to find out what students know, so it is important in assessing their progress. Questions can also be used to inspire, extend students’ thinking skills and develop enquiring minds. They can be divided into two broad categories:

- Lower-order questions, which involve the recall of facts and knowledge previously taught, often involving closed questions (a yes or no answer).

- Higher-order questions, which require more thinking. They may ask the students to put together information previously learnt to form an answer or to support an argument in a logical manner. Higher-order questions are often more open-ended.

Open-ended questions encourage students to think beyond textbook-based, literal answers, thus eliciting a range of responses. They also help the teacher to assess the students’ understanding of content.

Encouraging students to respond

Many teachers allow less than one second before requiring a response to a question and therefore often answer the question themselves or rephrase the question (Hastings, 2003). The students only have time to react – they do not have time to think! If you wait for a few seconds before expecting answers, the students will have time to think. This has a positive effect on students’ achievement. By waiting after posing a question, there is an increase in:

- the length of students’ responses

- the number of students offering responses

- the frequency of students’ questions

- the number of responses from less capable students

- positive interactions between students.

Your response matters

The more positively you receive all answers that are given, the more students will continue to think and try. There are many ways to ensure that wrong answers and misconceptions are corrected, and if one student has the wrong idea, you can be sure that many more have as well. You could try the following:

- Pick out the parts of the answers that are correct and ask the student in a supportive way to think a bit more about their answer. This encourages more active participation and helps your students to learn from their mistakes. The following comment shows how you might respond to an incorrect answer in a supportive way: ‘You were right about evaporation forming clouds, but I think we need to explore a bit more about what you said about rain. Can anyone else offer some ideas?’

- Write on the blackboard all the answers that the students give, and then ask the students to think about them all. What answers do they think are right? What might have led to another answer being given? This gives you an opportunity to understand the way that your students are thinking and also gives your students an unthreatening way to correct any misconceptions that they may have.

Value all responses by listening carefully and asking the student to explain further. If you ask for further explanation for all answers, right or wrong, students will often correct any mistakes for themselves, you will develop a thinking classroom and you will really knowwhat learning your students have done and how to proceed. If wrong answers result in humiliation or punishment, then your students will stop trying for fear of further embarrassment or ridicule.

Improving the quality of responses

It is important that you try to adopt a sequence of questioning that doesn’t end with the right answer. Right answers should be rewarded with follow-up questions that extend the knowledge and provide students with an opportunity to engage with the teacher. You can do this by asking for:

- a how or a why

- another way to answer

- a better word

- evidence to substantiate an answer

- integration of a related skill

- application of the same skill or logic in a new setting.

Helping students to think more deeply about (and therefore improve the quality of) their answer is a crucial part of your role. The following skills will help students achieve more:

- Prompting requires appropriate hints to be given – ones that help students develop and improve their answers. You might first choose to say what is right in the answer and then offer information, further questions and other clues. (‘So what would happen if you added a weight to the end of your paper aeroplane?’)

- Probing is about trying to find out more, helping students to clarify what they are trying to say to improve a disorganised answer or one that is partly right. (‘So what more can you tell me about how this fits together?’)

- Refocusing is about building on correct answers to link students’ knowledge to the knowledge that they have previously learnt. This broadens their understanding. (‘What you have said is correct, but how does it link with what we were looking at last week in our local environment topic?’)

- Sequencing questions means asking questions in an order designed to extend thinking. Questions should lead students to summarise, compare, explain or analyse. Prepare questions that stretch students, but do not challenge them so far that they lose the meaning of the questions. (‘Explain how you overcame your earlier problem. What difference did that make? What do you think you need to tackle next?’)

- Listening enables you to not just look for the answer you are expecting, but to alert you to unusual or innovative answers that you may not have expected. It also shows that you value the students’ thinking and therefore they are more likely to give thoughtful responses. Such answers could highlight misconceptions that need correcting, or they may show a new approach that you had not considered. (‘I hadn’t thought of that. Tell me more about why you think that way.’)

As a teacher, you need to ask questions that inspire and challenge if you are to generate interesting and inventive answers from your students. You need to give them time to think and you will be amazed how much your students know and how well you can help them progress their learning.

Remember, questioning is not about what the teacher knows, but about what the students know. It is important to remember that you should never answer your own questions! After all, if the students know you will give them the answers after a few seconds of silence, what is their incentive to answer?

Additional resources

- A selection of multilingual activities: http://mlenetwork.org/ content/ activities-early-grades-mother-tongue-l1-based-multilingual-education-programs

- The Rishi Valley rural education programme has published a number of different resources, some of which include pictures, poems in state and local languages: http://rishivalley.org/ publications/ list_of_titles.htm

- Some stories from Rishi Valley told in Hindi with downloadable written version and worksheets: http://rishivalley.org/ rvite/ Stories%20with%20Worksheets.htm

- Articles from Rishi Valley in Hindi and English about teaching Hindi to children: http://rishivalley.org/ rvite/ articles_teaching_hindi_children.htm

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Figure 1: left, ‘My Village’ and right, ‘Agriculture’, © local artists – unidentified.

Figure 2: NCERT, Rimjhim, Hindi, Class 1, Chapter 2: http://ncert.nic.in/ NCERTS/ textbook/ textbook.htm?ahhn1=2-23.

Figure 3: Credit: Vidya Bhawan Education Resource Centre, Udaipur.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.