Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 7:35 AM

TI-AIE: Early reading

What this unit is about

In this unit you will learn how to teach, support, plan for and assess early reading in your classroom. Reading is perhaps one of the most important and empowering skills your students will acquire. Your role in supporting and encouraging your students’ early reading is key to their future educational and life success.

Learning to read is not an innate developmental process. Rather, it involves regular practice over a period of time. Such practice may occur informally (at home or in the community) and formally (in school). There are many pathways to reading, some of which you will have taken yourself.

The fact that you are a teacher indicates that you are a skilled and confident reader who can read different types of texts for both information and enjoyment. In addition to reading texts in print, you may also read on a computer or a mobile phone screen. How did you learn this complex skill? In this unit you will reflect on the journey you have taken in becoming a reader, and on the journey that you are supporting your students through.

What you can learn in this unit

- How to plan early reading lessons that are engaging and enjoyable.

- How to identify behaviours that young students may exhibit during the early stages of learning to read.

- Ways of assessing and supporting early reading development.

Why this approach is important

Teaching early reading is much more than enabling children to recognise letters and words. It is about helping your students to make meaning from whole texts. This in turn improves their knowledge of language and their understanding of the world. Children who enjoy reading and become skilled and fluent readers tend to do well in all areas of school.

In order to ensure that all your students engage in and make progress with their reading, it is important that you:

- motivate and encourage them

- observe and assess them

- use the information that you gain from monitoring them to help you to plan the teaching and support that they need to develop this essential skill.

1 Beginning to read – ‘Who?’, ‘What?’, ‘Where?’, ‘Why?’

What do you remember about your early reading experiences? How do they compare to those described in the case study below?

Case Study 1: Memories of learning to read

In the following extracts, seven Indian teachers recall their early experiences of learning to read. As you read their recollections, make notes on who helped them to read, what they read, where they read and why they read.

- a.My mother told many traditional stories to amuse me and my sisters. Sometimes she wrote them out and illustrated them. She encouraged us to make our own picture books from recycled paper and cut-outs from magazines. I had a small collection of books that we made together.

- b.My grandfather was very strict. Every day he made me memorise five words from the dictionary. It was the only book in our home. Once, when he wouldn’t give me some money, I said to him ‘You are a miser!’ He was annoyed, but he also laughed. I had a large vocabulary, but I didn’t read any storybooks.

- c.When I was a child, my father used to read us a passage from the Vedas each evening. Then he would ask us to explain it. The passages were complex and difficult to understand. One day my elder sister secretly took the Vedas and read the next passage out to me. She explained its meaning very clearly so that I understood it. That evening my father was very pleased with me!

- d.My grandmother drew words on the ground with a stick and told me what they meant. These were the first words I read. Then my sister taught me to read from her school textbook. She did this because I was tall and appeared older than I was, and she worried that I would be teased if I went to school and could not read.

- e.In my home and village there were no reading materials. The first time I saw written words was when I went to school. My teacher was my inspiration. She told us lots of exciting stories while we sat on the floor and listened. I remember those stories to this day. She then wrote out the stories in big letters on chart paper so that everyone could see the words. Because I had already memorised the stories, I felt I could read them easily.

- f.My school teacher taught us to memorise poems. Over time these got longer and longer. It was fun to memorise a long poem! I would impress my parents by reciting poems to them. Sometimes they asked me recite a poem to visiting guests at home. I still can recite the Independence Day poem by Rabindranath Tagore. I love the way it starts: ‘When the mind is without fear/And the head is held high/Where knowledge is free…’. I didn’t read poems in books until I was much older.

- g.I did not enjoy reading until I was an adult. My school teacher only used the textbook in our classes. We read the lessons and did the exercises. The content was dull and far removed from my interests. The stories that I heard at home were much more exciting I liked staying up at night, listening to my uncles as they told stories from the Ramayana. When I was older, I liked going to the cinema. All films are stories, really.

Pause for thought What did your notes on these extracts reveal?

|

The above accounts show that learning to read is an interactive process that involves a range of people, sources of material and experiences. Do any of the practices and resources described feature in your classroom? Why or why not?

Activity 1: Your memories of learning to read

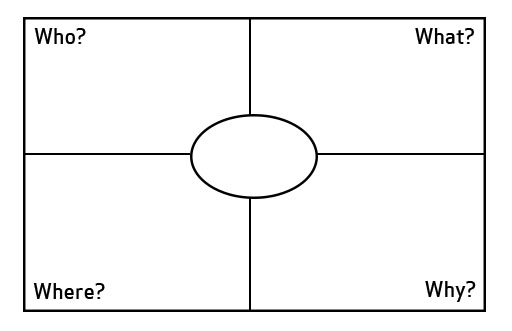

You will now reflect on your own memories of learning to read. Write your name in the centre of the chart in Figure 1 and complete the four other sections with your answers to the following questions:

- Who introduced you to reading?

- What did you read first?

- Where did you do this?

- Why did it happen?

Share your recollections with a colleague. What are the similarities and differences between your experiences of learning to read?

Do you draw on your early reading experiences in your classroom teaching? Why or why not?

Pause for thought Now look at the chart from the perspective of the students in your classroom. Instead of your own name in the middle of the chart, think about the students you teach.

|

Case Study 2: ‘Boxes on the Bus’

Mrs Lata, a Class I teacher in Indore, describes how she engaged her young students with a simple story called ‘Boxes on the Bus’ (see Resource 1).

The story is very simple: it’s about the different people who get on a bus, each of whom is carrying a box. Each box contains something different. Gradually the bus gets fuller and fuller until there is no room for anyone else.

Before telling the story, I thought of some items that the boxes could contain. I began by showing my students a big cardboard box that I had brought in from home. They were quite excited about it. I then recounted the story. Whenever I said the phrase ‘… and in the box was …’, I invited my students to join in. Among the items I included in the boxes were a button and a goat.

In each case, I asked a student to come to the front of the class and illustrate the item with an action. Labani curled her thumb and forefinger together to represent a button and Padmaj ‘walked’ four fingers up his arm to indicate a goat.

After I had told the story once, I retold it, pausing between each section so that my students could repeat it after me. I then told the story again, with my students reciting it while using actions at the same time.

Two days later, I paired up my students, combining the more confident ones with the less confident ones wherever possible, and asked them to retell the ‘Boxes on the Bus’ story to each other from memory.

Two students had missed the earlier lesson, so I selected pairs that could support them and explain what they had learnt, and placed the absent students with them in groups of three.

I then invited the whole class to help me cut out images from some colour magazines to match the content of the story, paste them onto the cardboard box that I had brought in and write words alongside to label them.

The following week, I found a picture book about a boat journey, which prompted me to think up an alternative version of the story – this time called ‘Boxes on the Boat’. For this version, I would ask my students to suggest what was in each box rather than telling them this myself.

Pause for thought Consider the following questions and discuss them with a colleague if possible:

Compare your ideas with ours. |

Students need to play an active part in early reading activities. The young students in Mrs Lata’s class were actively engaged in the ‘Boxes on the Bus’ story, because:

- they listened to the story together

- they used their voices and bodies by repeating the key phrase ‘… and in the box was …’, and by copying the actions invented by their classmates

- by decorating the box with pictures and labels, they were able to link the sounds within the familiar story to letters, words and phrases.

Students get great satisfaction from listening to an enjoyable story several times. It enables them to get to know the characters, anticipate what will happen next and retell the story themselves.

Activity 2: Locating resources to enhance a simple story

For this activity you will plan some early reading activities based on the ‘Boxes on the Bus’ story in Case Study 2, or an alternative story of your choice. Begin by looking around your classroom, school, home and community. What resources are available to enhance the telling of the story? Consider the following:

- suitable objects

- pictures

- people who can contribute

- materials to make things from.

Note down as many ideas as possible for enhancing the story using the resources you have identified. Here are some suggestions:

- Many stories may be illustrated by pictures or objects. For the ‘Boxes on the Bus’ story, you may have located boxes of different sizes, a toy bus, a poster image of a bus, and a number of small objects or magazine pictures to illustrate the items contained in each box.

- Did you think of any people who could contribute to the telling of the story? Does a family member of a student in the school drive a bus? If so, either they – or perhaps the student, if older – could be invited to talk about this.

- Together with your students, you could make a poster of words and pictures from the story.

- You could also organise a simple role play, with one student as the bus driver. Divide the class into two groups. Those in one group each carry a box with something inside it onto the bus. Those in the other group must guess what is in each box. Alternatively, you could make up a tune and get your students to sing the story.

Make a plan to try out your ideas and resources in your classroom. Bear in mind that several short activities over the course of a few days are more effective in reinforcing young students’ learning than one or two longer ones. Discuss your ideas with your colleagues and then implement your lesson plan.

Pause for thought

|

Storytelling – recounting stories from memory – is one way of introducing your students to reading. It familiarises them with the flow of stories and stimulates their interest in what happens next. You can assess what they learn by their responses to your questions about the story, and whether they can retell the story on their own, or with your support. Be sure to check the understanding of all your students and retell the story in different ways if you think they haven’t been able to follow it.

Another way to support your students’ in developing early reading skills is through reading books aloud to them.

2 Reading aloud to your students

By reading books aloud and following the words on the page with your finger as you do so, you will help your students to understand that print carries meaning. They will learn how to hold a book and turn the pages, and how texts are sequenced from beginning to end, left to right and top to bottom.

As you model good reading practices, your students will copy you. They will try to ‘read’ books independently, sometimes recalling the words of a story from memory, using the pictures as prompts and sometimes making up the story themselves, drawing on their experience and imagination. These are all encouraging signs that they are developing reading practices, so be sure to notice and encourage them as they do so.

Case Study 3: A reading role model

Ms Saroj is an elementary teacher in Bihar. Here she describes how she tries to be a reading role model for her young students.

Whether it’s a poem or short story, I read aloud to my students every day. I open the book very deliberately, turn the pages carefully, select a poem or story, and read it with expression, following the text with my finger and showing my students the accompanying illustrations. I often read the same poem or story more than once on different occasions.

Since I have been doing this, I notice that my young students have started to handle books more carefully, holding them the right way up, turning the pages one by one, looking at the pictures attentively and, sometimes, moving their fingers under the words. By observing them in turn – noting which of them is looking at the pictures, pretending to read, attempting to read or reading most or all of the words – I can monitor their individual progress in developing this skill.

Activity 3: Reading aloud to your students

Using Case Study 3 and Resource 2 for reference, plan, implement and evaluate your own reading aloud session with your students. Discuss your ideas and reflections with a colleague if possible.

The next section describes some of the strategies that young students use in their early reading.

3 Pathways to reading

Young students learn to read in different ways:

- Listening to stories and repeating the language they hear. In so doing, they internalise and read ‘chunks’ of language – that is to say, expressions, phrases and sentences.

- Reading each letter and word in turn, knowing exactly what words are composed of and what each word means.

- Using pictures to help them read and understand the words on the page.

Most students in fact employ a mixture all of these strategies.

Case Study 4: Ms Daima’s students’ reading strategies

Ms Daima, a Class I teacher in Madhya Pradesh, describes some of her young students’ reading strategies.

Nabhi was an enthusiastic and dramatic storyteller. She regularly told stories to her classmates. Some of them were recounted from memory, while others were invented then and there. She listened very carefully when I told a story to the class, repeating the key words and phrases as I did so. When Nabhi read aloud on her own, she made some mistakes, such as saying ‘horse’ instead of ‘donkey’, but her word substitutions always made sense. I decided to encourage Nabhi to read some simple reading books to improve her word recognition. I gave her a book about colours. Nabhi looked at the cover of the book, turned the pages quickly, and said excitedly ‘This is a book about the colours! It’s all about where you can see red things, yellow things, blue things – on the car, in the street, in the house, in the flowers. I can read this!’. Gently I encouraged Nabhi to read each word.

Bachan was keen to be accurate in his reading. He would sound out the letters of each word slowly and correctly. When he came to a word he did not know, Bachan would stop reading. As he struggled, he would lose the meaning of the text and become discouraged. I decided to encourage him to listen to my stories and retell them in his own words. I also invited him to read aloud along with me and other students, and urged him not to worry if he made small mistakes.

Pramila enjoyed listening to the stories that I read aloud in class. I often noticed her reading the same storybooks aloud afterwards. One day, when she was absorbed in a book containing pictures and simple sentences, I asked her if she could read a page to me. She recounted the story accurately but did not look at the text or point to any of the words on the page. I praised her, covered up the pictures and asked her to tell me the story again. With no pictures to guide her, this time she struggled. When I uncovered the pictures, however, she was able to continue. She had memorised the story but was still learning to read. I read along with her, pointing to each word at the same time so that she would begin to associate the text with the story that she knew so well.

In the case study, Ms Daima noticed that her students used distinct strategies to learn to read and took steps to support each of them further.

Pause for thought

|

There is no single pathway to reading. Teachers should therefore encourage their students to try different ways of mastering and practising this complex skill.

Resource 3 provides more ideas on how to monitor and give feedback to your students effectively. Giving encouraging feedback to your students can support them in developing their early reading.

Activity 4: Observing reading in your classroom

In order to be able to offer your students appropriate support, it is important to establish what kinds of reading strategies they use. A table can be a useful way of noting this information. This information will then enable you to plan how best to support their reading development. A sample is provided below in Table 1.

As you observe your students in turn, insert their name under the reading strategies that apply to them. You might find it helpful to practise first by assessing Nabhi, Bachan and Pramila’s reading strategies as described in Case Study 4 above. Be sure that you complete the table for all those in your class over time.

| Guesses | Memorises | Uses pictures to predict | Predicts using first letter of a word | Reads each individual word | Reads chunks of text | Points to each word | Moves finger under sentences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Do some of your students use a mix of strategies?

Have you observed any other strategies that your students use? If so, add these to your table.

Identify those students who use similar strategies and group them accordingly. Plan your lessons so that you can respond to their different needs over time. Some students may need individual support from you.

With others you may be able to work in small groups. Consider pairing readers who use different strategies to see if they can learn from each other.

Use copies of the table to develop records of the reading progress of your young students over the school year.

You may also find it helpful to read the key resource ‘Assessing progress and performance’.

Video: Assessing progress and performance |

4 Summary

Teaching early reading should be an interactive, engaging and enjoyable process. Whether it involves storytelling or reading aloud, it should provide children with opportunities to repeat phrases, use actions, guess what is going to happen next, recall the story later, and do related drama or art activities.

With young students, a short reading session each day is more effective than longer, more infrequent sessions. When students see models of reading and regularly handle books, they will attempt to read themselves.

There are many pathways to becoming a reader. Through enjoyable activities, practice and support over time, your students can become fluent, confident readers, thereby gaining a sound foundation for their future learning.

Resources

Resource 1: ‘Boxes on the Bus’

The bus stopped at the station. An old man got on the bus. He was carrying a brown box, and in the box was … [a hat]. Then a mother and her baby got on the bus. She was carrying a tiny white box, and in the box was … [a bracelet]. Next, a woodcutter got on the bus. He was carrying a very long wooden box and in the box was ... [an axe]. Then a cook got on the bus. She was carrying a flat, round box, and in the box was … [a roti].

Continue the story for as long as you like. When the bus gets too crowded, the driver says, ‘I can’t take any more people or boxes! Doors closing! Beep beep!’

You can add to the complexity of the story by describing the shape, colour and material that the boxes are made of, as above, and make their contents more challenging by adding descriptive words or referring to plural or non-countable items (for example, ‘He was carrying a heavy metal box and in the box was a pair of old leather shoes/some flour/three fat chickens’), or to noises coming from the boxes (such as ‘She was carrying a very small box and in the box was a squeaking sound’). The story can also introduce students to different occupations and the tools people use in their jobs.

As the list of boxes and their contents gets longer, the story thus becomes a memory game.

Resource 2: Reading aloud session plan

Preparation

- Choose a simple story to read aloud. The book will need to be big enough for all your students to see the words and pictures.

- Make sure you are familiar with the story in advance.

- Practise reading it with expression to a colleague at school or to your family at home, holding the book so that students can see it at the same time as you are reading it.

- Note any unfamiliar words or concepts, bearing in mind that some students will be less confident in the school language.

Before reading the story

- Gather your students around you so that they can see the book clearly.

- Talk to your students about something they might have experienced that is related to the theme of the story.

- If there are key words in the story that your students may not know, introduce these and talk about their meaning. This is particularly important for students whose home language is different from the school language.

- Introduce the book by showing your students the cover. Point to and read out the title. Talk about the picture on the cover and ask your students if they can guess what the story is about.

Reading the story

- Read the text in an expressive way, using different voices for each character.

- Move your finger under the words of the sentences as you read them.

- Ask your students to describe what is happening in the accompanying pictures:

- ‘What do you see in the picture?’

- ‘What do you think is happening?’

- Where appropriate, before turning to the next page, invite your students to predict what is

- What will happen next, I wonder?’

- ’What do you think will he say now?’

Talk about the story. Ask your students questions such as:

- Which part did you like best?’

- ‘Who was your favourite character? Why?’

With young students, do not expect detailed answers. Let the discussion be enjoyable as you model the process and pleasure of reading. Don’t forget to express your own opinions too!

Opportunities for assessment

- How did your students respond to the story that you read to them?

- Did some of them appear not to be following it? If so, why might that have been?

- Did any of them use any of the key words or expressions in it afterwards?

- Did you notice any students picking up the book later and looking at it independently, copying your reading behaviour?

Resource 3: Monitoring and giving feedback

Improving students’ performance involves constantly monitoring and responding to them, so that they know what is expected of them and they get feedback after completing tasks. They can improve their performance through your constructive feedback.

Monitoring

Effective teachers monitor their students most of the time. Generally, most teachers monitor their students’ work by listening and observing what they do in class. Monitoring students’ progress is critical because it helps them to:

- achieve higher grades

- be more aware of their performance and more responsible for their learning

- improve their learning

- predict achievement on state and local standardised tests.

It will also help you as a teacher to decide:

- when to ask a question or give a prompt

- when to praise

- whether to challenge

- how to include different groups of students in a task

- what to do about mistakes.

Students improve most when they are given clear and prompt feedback on their progress. Using monitoring will enable you to give regular feedback, letting your students know how they are doing and what else they need to do to advance their learning.

One of the challenges you will face is helping students to set their own learning targets, also known as self-monitoring. Students, especially struggling ones, are not used to having ownership of their own learning. But you can help any student to set their own targets or goals for a project, plan out their work and set deadlines, and self- monitor their progress. Practising the process and mastering the skill of self-monitoring will serve them well in school and throughout their lives.

Listening to and observing students

Most of the time, listening to and observing students is done naturally by teachers; it is a simple monitoring tool. For example, you may:

- listen to your students reading aloud

- listen to discussions in pair or groupwork

- observe students using resources outdoors or in the classroom

- observe the body language of groups as they work.

Make sure that the observations you collect are true evidence of student learning or progress. Only document what you can see, hear, justify or count.

As students work, move around the classroom in order to make brief observation notes. You can use a class list to record which students need more help, and also to note any emerging misunderstandings. You can use these observations and notes to give feedback to the whole class or prompt and encourage groups or individuals.

Giving feedback

Feedback is information that you give to a student about how they have performed in relation to a stated goal or expected outcome. Effective feedback provides the student with:

- information about what happened

- an evaluation of how well the action or task was performed

- guidance as to how their performance can be improved.

When you give feedback to each student, it should help them to know:

- what they can actually do

- what they cannot do yet

- how their work compares with that of others

- how they can improve.

It is important to remember that effective feedback helps students. You do not want to inhibit learning because your feedback is unclear or unfair. Effective feedback is:

- focused on the task being undertaken and the learning that the student needs to do

- clear and honest, telling the student what is good about their learning as well as what requires improvement

- actionable, telling the student to do something that they are able to do

- given in appropriate language that the student can understand

- given at the right time – if it’s given too soon, the student will think ‘I was just going to do that!’; too late, and the student’s focus will have moved elsewhere and they will not want to go back and do what is asked.

Whether feedback is spoken or written in the students’ workbooks, it becomes more effective if it follows the guidelines given below.

Using praise and positive language

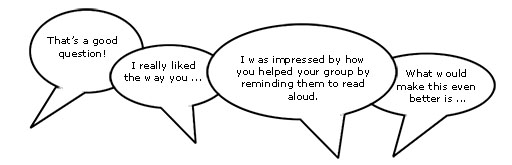

When we are praised and encouraged, we generally feel a great deal better than when we are criticised or corrected. Reinforcement and positive language is motivating for the whole class and for individuals of all ages. Remember that praise must be specific and targeted on the work done rather than about the student themselves, otherwise it will not help the student progress. ‘Well done’ is non-specific, so it is better to say one of the following:

Using prompting as well as correction

The dialogue that you have with your students helps their learning. If you tell them that an answer is incorrect and finish the dialogue there, you miss the opportunity to help them to keep thinking and trying for themselves. If you give students a hint or ask them a further question, you prompt them to think more deeply and encourage them to find answers and take responsibility for their own learning. For example, you can encourage a better answer or prompt a different angle on a problem by saying such things as:

It may be appropriate to encourage other students to help each other. You can do this by opening your questions to the rest of the class with such comments as:

Correcting students with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ might be appropriate to tasks such as spelling or number practice, but even here you can prompt students to look for emerging patterns in their answers, make connections with similar answers or open a discussion about why a certain answer is incorrect.

Self-correction and peer correction is effective and you can encourage this by asking students to check their own and each other’s work while doing tasks or assignments in pairs. It is best to focus on one aspect to correct at a time so that there is not too much confusing information.

Additional resources

- Annual Status of Education Report 2012, published by ASER Centre: http://www.asercentre.org/ education/ India/ status/ p/ 143.html

- Room to Read, India: http://www.roomtoread.org/ Page.aspx?pid=304

- A useful site for explaining what reading involves: http://www.readingrockets.org/ article/ 352

- Traditional Indian stories: http://www.indiaparenting.com/ stories/ index.shtml#77

- Knowledge, behaviours and activities for early readers: http://www.siue.edu/ education/ readready/ 1_Literacy/ 1_SubPages/ 1_ld_emergent.htm

- Resources to improve students’ reading and writing in school: http://fdf.readingrecovery.org/ resources

- Phonemic awareness activities: http://teams.lacoe.edu/ documentation/ classrooms/ patti/ k-1/ activities/ phonemic.html

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.