Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:28 AM

3 Communication and cognitive issues

3.1 Introduction

Having worked through the course up to the end of Section 2, you should now have a general understanding of the motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s. You should also understand the impact that these symptoms can have on the quality of life of a person with Parkinson’s and how you can help them manage these symptoms. In this section we will look in detail at communication and cognitive problems, as these can have a significant impact on a person with Parkinson’s and those who care for them. You can consider your role and that of other professionals in managing these problems.

In this section, we will look at the following questions:

- What communication problems are caused by Parkinson’s?

- What is the impact of these problems and what assumptions could be made about people with communication difficulties?

- How can communication problems be managed?

- What cognitive problems are caused by Parkinson’s and how can you care for someone with cognitive problems?

This section begins with a short video of Joyce Quillietti, whose partner has Parkinson’s. She introduces the discussion of communication and cognitive issues by reflecting on how she and her family experience these issues.

Transcript

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

Learning outcomes

The purpose of Section 3 is to give you an understanding of the processes, procedures, methods, techniques and services used to manage communication and cognitive issues in Parkinson’s.

By the end of this section you should be able to identify and describe the following:

- the key communication and cognitive challenges of Parkinson’s

- the impact these challenges may have on the individual and those around them

- the range of techniques used to address common communication and cognitive challenges, and the appropriate situations in which to use them.

3.2 What communication problems are caused by Parkinson’s?

Exercise 3.1

We communicate with each other in lots of different ways. Think about all the different ways you communicate with your family, friends and colleagues and write your thoughts down in your reflection log.

When you think about all the different ways we communicate, can you guess what percentage of our face-to-face communication is done in the following ways?

- Talking

- Gesture and tone

- Body language

Answer

These figures come from the book Silent Messages: Implicit communication of emotions and attitudes by Albert Mehrabian. In this book, Mehrabian discusses how important certain aspects of face-to-face communication are in relation to one another. Most people are very surprised at the answers:

- talking: 7%

- tone: 38%

- body language: 55%.

People with Parkinson’s may find they have problems with different kinds of communication, including speech, facial expressions and writing. Many people will be surprised at how low the percentage of 7% is for talking. It is true that we need words to communicate, but words themselves can often have different meanings – it is the way in which we say these words that communicate what we really mean.

Speech

Many people with Parkinson’s have speech problems that may make everyday activities, such as talking to friends or using the phone, difficult. For example, their speech may be slurred, and their voice hoarse, unsteady or quieter than it used to be. People might find it hard to control how quickly they speak – this can make it difficult to start talking and may make their speech get faster. Some people with Parkinson’s also find that their voice can be monotone.

When we talk, our gesture and tone help us to convey meaning much more than words. We saw that Albert Mehrabian said 38% of our communication is tone. Think about how meaning can be misconstrued when you send an email or text. How often have you given the wrong impression through an email? Now consider the impact that this can have on someone with Parkinson’s who has speech difficulties.

These problems can make it hard when a person is talking to another or in a group situation. Taking turns to speak, following fast-changing topics or interrupting might be difficult, and so people with Parkinson’s may find themselves giving minimal responses or withdrawing from socialising altogether.

People with Parkinson’s can also experience slowness of thought (bradyphrenia). When you ask a person with Parkinson’s a question it can often take much longer for them to listen to what you said, think about their response and then articulate it than it does for people without Parkinson’s. This can become even more difficult when people are stressed or anxious.

Facial expressions and body language

Some people with Parkinson’s can have issues with facial expression because of difficulty controlling facial muscles. This is called hypomimia. Sometimes a person may make an expression that they didn’t plan to make. At other times they may find it difficult to smile or frown. This can make it hard for people with these symptoms to show how they feel about a situation or something being said.

Transcript

[Music playing]

You can download this resource and view it offline. It may be useful as part of a group activity.

Albert Mehrabian suggests that body language is 55% of our communication. All of us are experts in reading body language – we do it every day without even thinking about it. Most of us express how we feel by how we stand, the position of our head and if we look relaxed or not.

Body language can also be affected by Parkinson’s symptoms – this can include slowness of movement, stiffness and tremor. These symptoms can reduce body or hand gestures, and make head and neck movements more restricted. Starting movements can be hard and can become slower and clumsier.

Involuntary movements (also known as dyskinesia) can be a side effect of Parkinson’s medication. These can affect any part of the body, including the face and mouth. As a result, people with Parkinson’s may be unable to control their movements well enough to speak or to communicate.

Handwriting

Many people with Parkinson’s experience problems with handwriting. This can be caused by tremor, lack of coordination, stiffness and a difficulty controlling small movements.

People may find their handwriting becomes spidery or difficult to read, or becomes smaller as they write (this is known as micrographia).

3.3 The impact of communication difficulties

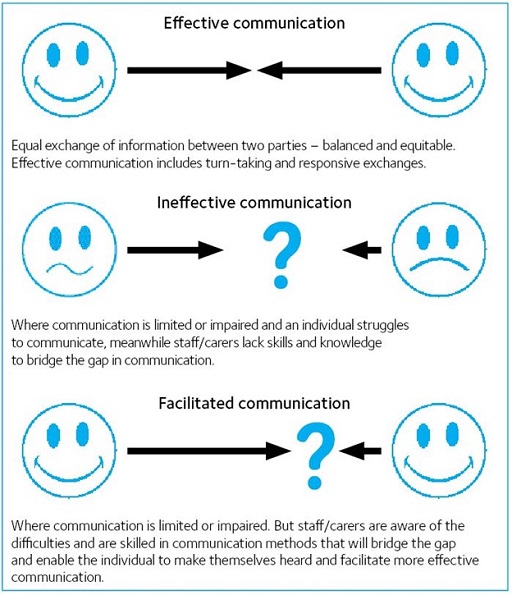

It is important to consider the impact of these symptoms and what assumptions are sometimes made about people with communication difficulties.

Difficulties with communication can be upsetting and frustrating for the person with Parkinson’s and for those around them. If you don’t understand the communication problems caused by Parkinson’s, it can often result in misunderstandings. Sometimes people may assume that those who experience these symptoms are being rude, or they are stupid or deaf. So make sure you don’t make these assumptions.

Think about what you have just read and the exercises you have completed. Now consider a person with Parkinson’s. Their speech may be slurred and quiet, and they may have slowness of thought. They may also have rigid facial muscles, which means they are unable to smile or show emotion on their face.

In an environment where people may not be able to do things by themselves, it can be incredibly upsetting and frustrating if a person is unable to communicate what they need. In your role you must give the person time to respond and try to take the lead in initiating conversation. Understand that although the person might not look or even sound like they are interested in you and what you have to say, this is not necessarily the case.

Exercise 3.2

If they don’t understand Parkinson’s, some assume that people living with the condition are stupid, deaf, rude or even drunk because of the challenges we have discussed. Can you think of a work situation where you have had difficulties in communicating with a person you were or are caring for? What assumptions did you make, what happened and what would you do differently now? Note down your thoughts in your reflection log.

3.4 Managing communication problems

There are a number of ways that communication problems can be managed, including the use of medication, speech and language therapy, and physiotherapy. Consider your role and that of other professionals in managing these.

Medication

Parkinson’s medication, such as levodopa, might help improve the volume and clarity of a person’s speech.

However, in some cases, Parkinson’s medication can contribute to speech problems. ‘On/off’ is a potential side effect of levodopa and some other Parkinson’s medication. ‘On’ means the person’s drugs are working and symptoms are well controlled, and ‘off’ is when there is suddenly no response to medication, and their symptoms become much more of a problem. Medication can also wear off slowly before the next dose.

As well as affecting movement, ‘on/off’ can affect speech and body language. For instance, a person’s voice may be louder and easier to understand when they are ‘on’, but be quiet and difficult to understand when they are ‘off’. This can be really frustrating for both the person with Parkinson’s and others around them.

Speech and language therapy

Speech and language therapists are healthcare professionals who can help with all aspects of communication, from facial expression and body language to speech and communication aids.

Speech and language therapy should be available to everyone living with Parkinson’s, so we suggest that you organise a referral for your client. The speech and language therapist may be able to suggest exercises and techniques to overcome some of the challenges that people with Parkinson’s are experiencing. They can also provide advice on alternative means of communication. These may include communication aids.

Physiotherapy

A physiotherapist will use physical treatments, including exercise, to help manage any stiffness in people’s joints and restore the strength in their muscles. This might help to improve people’s ability to move and make it easier to control their body language.

Action to take

Difficulties with communication can be upsetting and frustrating for the person with Parkinson’s and for those around them. But there are some basic things you might try to make life a little bit easier:

- Be patient and give the person affected time to talk. They may need extra time to talk and respond, so try not to interrupt them or walk away.

- Try not to talk for them, unless it’s absolutely necessary. Don’t insist they pronounce each word perfectly and avoid finishing their sentences.

- Take the lead in initiating conversation. Give people the opportunity to talk and encourage them to join in the conversation if it’s appropriate, but don’t pressure them to speak.

- Don’t ignore the person affected by asking someone else to speak for them.

- Remember that someone may not look or sound like they are interested in talking to you, but this may not be the case.

- Talk normally and don’t shout.

- Listen carefully.

- Vary the tone of your voice and relax. Stress can be heard in your voice.

- Use short sentences and stress key words. It will also help not to ask difficult questions or more than one question at a time.

- Make sure they can see and hear you.

- Be reassuring and help the person affected to relax if they are visibly stressed when trying to talk. For example, they might appreciate it if you hold their hand if they are having trouble speaking.

- If you didn’t understand what someone has said, ask them to repeat it - but louder or in another way. Try not to pretend you have understood if you haven’t.

- Try to avoid speaking above noise, such as a TV or radio, and try not to be too far away, for example, in another room when talking.

- Try not to make a person with Parkinson’s talk while doing another activity, such as walking. It can be difficult for some people to multi-task.

3.5 Communication in Parkinson’s – case study

Case Study 3.1 Geoff and Pat

We have considered the communication problems that can be caused by Parkinson’s, as well as their impact and how to manage them. Now we will look at the real experiences of Geoff and Pat.

Geoff, who is 73 and was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2016, and his wife Pat, share their experience of communication difficulties before Geoff got help.

Geoff says:

I put almost everything I could no longer manage down to Parkinson’s and hence it needed no action on my part. I could not ‘help’ it and others should adapt to compensate.

Any criticism or request for change was rejected. If Pat could not hear me, it was her problem not mine. I had begun to avoid situations when I would need to speak, and I stopped answering the phone and zoned out of family social activities,for example chatting over meals and with friends, and reading to my grandson. I’d lost my confidence and willingness to engage with others.

I did not realise how my quiet voice and lack of responses in conversations was affecting my relationships,with family, friends and colleagues.

I felt bad about myself, anxious, negative and introverted. I didn’t smile or laugh as much as I used to. Life wasn’t fun any more.

Pat says:

Geoff’s voice had become much quieter and had less expression. He had stopped opening conversations and when asked a question would reply with very limited answers.

In the car he had stopped chatting to me. In the evenings he would sit, not communicating at all, or doze off to sleep. This did start to impact our previously busy social life. Friends reduced contact with us and invitations were not extended. I began to overcompensate and talk more and more as he became more silent.

Geoff recognised his voice had become quieter, but I think he had put this down to my own hearing loss. Despite my hearing aids, he assumed it was my imagination when I said I couldn’t hear him.

Family and friends all shared with Geoff that his voice had become too quiet for normal conversation.

Thinking quickly, formulating answers on the spot, and responding to random questions was something Geoff found difficult. I would speak for him or move conversations along by intervening.

The old Geoff had gone. There was no laughter in his voice, and he no longer made jokes.

Exercise 3.3

Please note down your answers to the following questions in your reflection log:

- What communication and other Parkinson’s challenges are Geoff and Pat living with?

- What health and social care professionals may be able to help?

- What could you do to help?

Answer

- What issues and challenges are Geoff and Pat living with?

- denial

- side effects of medication

- anxiety

- frustration

- isolation

- loss of senses of humour

- loss of friends

- changes to Sheila’s lifestyle

- difficulties with communication – slow to get words out, flat facial expression, flat tone of voice, embarrassment at not being understood.

- What or who could have helped?

- speech and language therapist

- Parkinson’s nurse or GP to help with anxiety and review drugs

- signpost to Parkinson’s local group

- mental health professional (such as a counsellor or community psychiatric nurse).

- What could you have done to help?

- refer Geoff to a speech and language therapist

- recommend the LSVT LOUD speech treatment

- make sure medication is taken on time

- allow plenty of time for Geoff to answer questions

- ask only one question at a time

- reassure Geoff that it’s OK to take a while to answer

- don’t decide what Geoff wants, wait until he can tell you

- encourage Pat to not answer for Geoff or interrupt him

- encourage Pat to explain Geoff’s condition to their friends

- encourage Geoff and Pat to think about joining smaller social gatherings and possibly a Parkinson’s UK local group – depending on your job role you may need to highlight this as an option, because people may not know about Parkinson’s UK local groups.

Since receiving speech therapy, Geoff's voice has got louder and his confidence has returned. He says that "life is fun again."

You can read Geoff and Pat’s full story at https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/ information-and-support/ your-magazine/ stories/ our-experiences-lee-silverman-voice-treatment

3.6 Cognitive problems and their management

We will now look at what cognitive problems are caused by Parkinson’s and how to care for someone with cognitive problems.

Cognitive problems are difficulties with thinking and memory. Many people with Parkinson’s will experience cognitive difficulties as a result of their Parkinson’s or as a side effect of their Parkinson’s medication. This means that some of their thinking processes and functions will be lost or become much slower. They may also experience changes in mood and motivation. These difficulties can be upsetting for the person with Parkinson’s, their family and their carer.

We will now explore some of the more common cognitive problems associated with Parkinson’s and helpful hints on what you can do to help those experiencing them.

3.7 Depression

It can be common for people with Parkinson’s to experience depression. Symptoms can feel overwhelming, but with the right help, support and treatment, individuals can manage depression and enjoy a good quality of life.

Depression is usually diagnosed when you have feelings of extreme sadness or a sense of emotional ‘emptiness’ for a long time. It’s more than temporary feelings of sadness, unhappiness or frustration.

Other symptoms of depression may include difficulties concentrating, low energy and tiredness, trouble sleeping or excessive sleeping, a loss of appetite and decreased interest in sex. In severe cases, some people may have thoughts of death, suicidal ideas and thoughts of self-harm.

Some symptoms of depression, such as fatigue, are also common symptoms of Parkinson's. It is important to understand the cause of the symptom – is it a symptom of Parkinson's in its own right, or is it a symptom of depression?

‘I’d been a social butterfly. I was very outgoing. Now I didn’t want to go out at all. These feelings were totally alien to me.’

Causes of depression in Parkinson’s

Depression can have a number of contributory factors, one of which is neurobiological with the chemical changes occurring in the brain. However we also need to consider significant psychological and social factors as well, such as changes in identity, grieving process along with changes in relationships and expectations of the future.

Some people may be more prone to depression at times when their Parkinson’s symptoms suddenly worsen or new problems emerge, perhaps as a drug begins to become less effective. Sometimes stressful life changes such as having to stop driving or give up a much-loved hobby, may result in a period of depression.

If you notice any of these changes in a person with Parkinson’s, you may wish to suggest a medical review. It is very important to make sure that Parkinson’s symptoms are as well controlled as possible.

Other causes of depression-like symptoms

Whether a person has Parkinson’s or not, depression could also be related to other physical conditions, such as thyroid problems, nutritional deficiencies (such as low vitamin B12 and folate levels) or anaemia.

Some people may be under-medicated for the physical symptoms of Parkinson’s – or depression could be a side effect of other drugs.

Treating depression

'Medication, such as antidepressants, can help treat moderate to severe depression within Parkinson's. They can be prescribed alone or alongside a course of talking therapy. The prescriber will need to take a full medical history, including symptoms of Parkinson's and current Parkinson's medication, to ensure that the antidepressant is not contra-indicated.

Not a lot is known about treating depression in Parkinson’s, but there are some things people can try. The treatment of depression has to be tailored to each person with Parkinson’s, because some medications for depression have the potential to make symptoms of Parkinson’s worse. Treatments should be introduced step by step, starting with the simplest measures.

It is very important to first make sure that a person’s Parkinson’s symptoms are as well controlled as possible. This may mean making changes to their medication regime.

Other recommendations for the treatment of depression include complementary therapies, regular sleeping times, gentle exercise, counselling.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK complementary therapies information.

Sometimes you may recognise the symptoms of depression more clearly than the person themselves. If this is the case, share your concerns with your manager or recommend an appointment with their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK information sheet on depression.

Actions to take

- Be aware of changes in emotions and any link with communication problems.

- Report any changes in mood to your manager and organise an appointment with the person’s specialist or Parkinson’s nurse. The person may need a change in drug treatment, but if they are regularly unhappy or negative, they may need further treatment.

- Encourage people to take part in activities and ensure that you take time to talk to them as much as you can.

- Remember the treatment of depression has to be tailored to each person with Parkinson’s. Medication for depression may be difficult to combine with their other drug treatment.

3.8 Anxiety

Some people with Parkinson’s experience feelings of anxiety. These can be intense, especially if their physical symptoms aren’t under control.

Anxiety is a feeling that everyone feels from time to time. It is a natural reaction to a dangerous or threatening situation. It disappears when the situation changes, if we get used to the situation, or if we leave the situation. But some people become anxious for long periods of time.

Symptoms of anxiety include worrying too much, difficulties concentrating or feeling tense. Some people may experience physical symptoms too, including sweating, dizziness, heart palpitations and nausea.

Severe anxiety can sometimes interfere with day-to-day life. At this point, anxiety is no longer a ‘normal’ reaction and may be considered as a mental health issue. A person with severe anxiety may also have symptoms of depression. Treating the depression can sometimes clear up the anxiety symptoms and vice versa.

Because anxiety can have physical symptoms, it may be difficult for people to tell the difference between symptoms of anxiety and the symptoms of Parkinson’s. Some people with Parkinson’s have anxiety related to the ‘on/off’ state of their motor symptoms. When ‘off’ and less able to move well, they may develop significant anxiety symptoms. When a person takes their medication, their symptoms may improve.

Physical symptoms

When anxiety is related to their physical symptoms, whether that’s a fear of falling or freezing, or being unable to communicate, people may develop panic attacks. This is something that many people find very difficult to manage.

Some people may find that when their physical symptoms are better controlled by medication, their anxiety improves. So it is important that the physical symptoms are managed effectively. If you think your client needs a review of their medication, make an appointment (or suggest that they should make an appointment) with their specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

When their drugs are wearing off, people with Parkinson’s might feel anxious, depressed or hopeless. After they’ve taken their medication, their mood may lift again.

Look for patterns in their anxiety episodes.

It is important to be able to recognise the symptoms of anxiety, so that they can be treated appropriately.

Treating anxiety

In the majority of cases, anxiety can be treated. For mild and occasional anxiety, identifying and avoiding triggers of anxious episodes and avoiding stimulants (tea, coffee and alcohol), especially late in the evening, can help. Where appropriate, exercise can also help to combat stress and relieve anxiety.

Complementary therapies, changes to Parkinson’s medication, counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy and medication for anxiety may also be helpful.

Anxiety can be a very difficult problem to live with and it may make it more difficult for someone to take part in normal day-to-day activities, such as going out or socialising.

Encourage the person with Parkinson’s to talk about their anxiety with you, as this may help you to understand how they are feeling. Knowing what they are going through may help you to be more patient in helping someone to manage their anxiety.

If you notice that the symptoms of anxiety are having a big effect on the quality of life of someone with Parkinson’s, report it to your manager or suggest that they see their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse. They may be referred to a mental health specialist who can recommend treatment.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK information sheet on anxiety.

Actions to take

- For mild anxiety it may be helpful to encourage the person to avoid stimulants such as caffeine and alcohol.

- Help the person to identify what triggers an anxious episode.

- Make sure that the person you are caring for has had a medical review to ensure their Parkinson’s medication is as effective as it can be.

- Some people find that relaxation exercises, such as yoga or massage, can be helpful in relieving symptoms of anxiety.

3.9 Mild memory problems

Some people with Parkinson’s experience mild memory problems (or mild cognitive impairment). This is when a person has problems recalling things, finding words and making decisions. People often experience this in the earlier stages of Parkinson’s. They may have problems with planning, multitasking, moving quickly from one activity to another or doing tasks in a particular order.

Problems with attention and concentration can make daily tasks, such as reading a newspaper article from start to finish, more difficult. People may also experience slow thought processes, so it could take longer to make decisions or respond in conversations.

If a person has had surgery for Parkinson’s, such as deep brain stimulation, they might have some specific problems with talking, concentration and complex thinking. However, some people who’ve had surgery have found that it improves their memory.

While many people can experience mild memory problems, this does not necessarily indicate a more serious problem such as dementia. It is vital that a person’s condition is reviewed by a specialist because sometimes it may seem like they are experiencing dementia symptoms, but they may actually have mild memory problems or other communication difficulties.

What are the causes?

We still don’t fully understand why thinking and memory problems occur. However, they could be caused by problems in the brain pathways that pass messages from one part of the brain to another.

Reasons other than Parkinson’s include anxiety and depression, sleep problems and an unhealthy diet.

Treating mild cognitive impairment

Some Parkinson’s medications, particularly levodopa, can improve thinking and concentration. But other Parkinson’s drugs, such as anticholinergic drugs and dopamine agonists, may have a negative impact on thinking, particularly in older people with more serious thinking and memory problems. We will look at these drugs in more detail in Section 4.

A person with Parkinson’s should see their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse about any memory or thinking problems as there may be medication that can help. They may also be referred to a psychologist.

Actions to be taken

If you think that thinking and memory problems are starting to affect a person’s daily life, there are techniques you can use to help them, including the following:

- Visual prompts: Calendars, clocks, noticeboards and notices around the home can help jog people’s memory and provide helpful reminders.

- Routine and organisation: Try to avoid change in their daily routine.

- Memory aids: A lot of people find medication dispensers useful to help remind them when to take their medication.

- Verbal strategies: Keep explanations clear and simple. You could also write messages down as well as talking to a person face to face.

- Maintain independence: Encourage people to stay as active as possible.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK information sheet on mild memory problems.

3.10 Parkinson’s dementia

So far in this section we have looked at a variety of cognitive problems in Parkinson’s, of which dementia is one. This is a complex symptom that we will explore in detail, including Parkinson’s dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies, their symptoms, causes and treatment, and information to support management of these symptoms.

Dementia symptoms are caused by a significant loss of brain function. There are different forms of the condition and each person will experience dementia in their own way.

Some people will develop dementia after living with Parkinson’s for some time. When someone has Parkinson’s motor symptoms for at least a year before experiencing dementia, this is known as Parkinson’s dementia.

Symptoms of Parkinson’s dementia

Symptoms can include forgetfulness, slow thought processes and difficulty concentrating. This can make communication hard, and finding words and names or following conversations can be a problem.

Some people find it increasingly difficult to make decisions, plan activities and solve problems. This can make everyday activities such as dressing, cooking or cleaning increasingly hard.

People can also experience changes in their appetite, energy levels and sleeping patterns. They may find themselves sleeping more during the day, or becoming less engaged with what’s going on around them. A lack of motivation or interest in things they previously enjoyed can also be a symptom.

Problems such as anxiety, depression or irritability can become an issue because of dementia. Some people may also find it difficult to control their emotions and experience sudden outbursts of anger or distress, although these problems are not common.

Some people with Parkinson’s dementia might also develop visual hallucinations and delusions.

Some of the symptoms of Parkinson’s dementia are similar to those caused by other health issues. For example, mental health issues such as depression can mimic dementia.

‘I moved in with Mummy in 2019. There was a concern for me. Mummy was burning food. There were signs that she needed more help.’

Side effects from medication or medical problems, such as an infection, may be the cause of symptoms similar to dementia, such as memory problems. Things like constipation and dehydration can also cause confusion. Symptoms caused by medication or infections can be treated effectively.

What are the causes?

We still don’t fully understand why some people with Parkinson’s get dementia and it isn’t entirely possible to predict who it will affect. But there are factors that put someone more at risk.

A person is more likely to develop dementia if they’re 65 or over, and their risk increases as they get older. A family history of dementia also increases risk.

They’re at a greater risk of Parkinson's dementia if they were diagnosed with Parkinson’s in later life, or have been living with the condition for many years.

If someone with Parkinson’s is experiencing hallucinations or delusions early on in their condition, this also suggests an increased risk of developing dementia.

If someone has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s later in life, has had Parkinson’s for a long period of time or has a family member with dementia, this can increase their risk of developing dementia.

Treating dementia

As with Parkinson’s, the symptoms of dementia can’t be cured, but they can be treated. This may be done by reviewing a person’s current medication and using dementia medications.

Medication can be helpful, but it’s also useful for people to get support from a wide range of healthcare professionals. Physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dietitians and speech and language therapists can help the person with dementia and those supporting them. You may be one of these healthcare professionals or you may be able to suggest a referral to one.

Helping with communication

The following information has been provided by the Alzheimer’s Society. You can find this and more helpful advice on the Alzheimer’s Society website.

Difficulties with communication can be upsetting and frustrating for the person with dementia and for those around them. But there are some basic things you can do to make life a little bit easier:

- Listen carefully to what a person with dementia says.

- Make sure you have their full attention before you speak.

- Pay attention to body language.

- Speak clearly.

- Consider whether any other factors are affecting their communication.

- Use physical contact to reassure the person.

- Show respect and keep in mind they have the same feelings and needs as they had before developing dementia.

Listening skills

- When communicating with a person with dementia, try to listen carefully to what they are saying, and give them plenty of encouragement.

- If a person with dementia has difficulty finding the right word or finishing a sentence, ask them to explain in a different way. Listen out for clues.

- If you find their speech hard to understand, use what you know about them to interpret what they might be trying to say. But always check back with them to see if you are right − it’s infuriating to have your sentence finished incorrectly by someone else.

- If someone is feeling sad, let them express their feelings without trying to ‘jolly them along’. Sometimes the best thing to do is to just listen, and show that you care.

Attracting the person’s attention

- Try to catch and hold their attention before you start to communicate.

- Make sure they can see you clearly.

- Make eye contact. This will help them focus on you.

- Try to minimise competing noises, such as the radio, TV or other people’s conversation.

Using body language

- Someone with dementia will read your body language. Agitated movements or a tense facial expression may upset them, and can make communication more difficult.

- Be calm and still while you communicate. This shows that you are giving them your full attention, and that you have time for them.

- Never stand over someone to communicate – it can feel intimidating. Instead, drop below their eye level. This will help them feel more in control of the situation.

- Standing too close to someone can also feel intimidating, so always respect their personal space.

- If someone is struggling to speak, pick up cues from their body language. The expression on their face and the way they hold themselves and move about can give you clear signals about how they are feeling.

Speaking clearly

- As the dementia progresses, people will become less able to start a conversation, so you may have to start taking the initiative.

- Speak clearly and calmly. Avoid speaking sharply or raising your voice, as this may distress them even if they can’t follow the sense of your words.

- Use simple, short sentences.

- Processing information will take someone longer than it used to, so allow enough time. If you try to hurry them, they may feel pressured.

- People with dementia can become frustrated if they can’t find the answer to questions, and they may respond with irritation or even aggression. If you have to, ask questions one at a time, and phrase them in a way that allows for a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

- Try not to ask the person to make complicated decisions. Too many choices can be confusing and frustrating.

- If the person doesn’t understand what you are saying, try getting the message across in a different way rather than simply repeating the same thing.

- Humour can help to bring you closer together, and is a great pressure valve. Try to laugh together about misunderstandings and mistakes − it can help.

Whose reality?

- As dementia progresses, fact and fantasy can become confused. If someone says something that you know is not true, try to find ways around the situation rather than responding with a flat contradiction.

- Always avoid making the person with dementia feel foolish in front of other people.

Physical contact

- Communicate your care by the tone of your voice and the touch of your hand.

- Don’t underestimate the reassurance you can give by holding or patting their hand, if it feels right.

Show respect

- Make sure no one speaks down to the person with dementia or treats them like a child, even if they don’t seem to understand what people say. No one likes being patronised.

- Try to include a person with dementia in conversations with others. You may find this easier if you adapt the way you say things slightly. Being included in social groups can help a person with dementia to keep their sense of identity. It also helps to protect them from feeling excluded or isolated.

- If you are getting little response from someone with dementia, it can be very tempting to speak about them as if they weren’t there. But disregarding them in this way can make them feel very cut off, frustrated and sad.

Other causes of communication difficulty

It is important to bear in mind that communication can be affected by other factors in addition to dementia, for example:

- Pain, discomfort, illness or the side effects of medication. If you suspect this might be happening, report it to your manager.

- Problems with sight, hearing or ill-fitting dentures. Make sure the person’s glasses are the correct prescription, that their hearing aids are working properly and that their dentures fit well and are comfortable.

- Parkinson’s symptoms can cause difficulties with communication.

3.11 Dementia with Lewy bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies is diagnosed when someone has the symptoms of dementia first and then develops Parkinson’s-like symptoms. In some cases of dementia with Lewy bodies, no motor symptoms may develop at all.

Symptoms of dementia with Lewy bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies affects a person’s memory, language, concentration and attention. It also affects their ability to recognise faces, carry out simple actions and their ability to reason. It tends to progress at a faster rate than Parkinson’s and may not respond well to Parkinson’s medications.

People with this form of dementia commonly experience visual hallucinations, which can be quite vivid. This can happen early on in the condition. They might also experience difficulty in judging distances and movements, which can cause them to fall over for no apparent reason.

The condition can also cause someone to experience episodes of confusion, which can change a lot from hour to hour or over weeks or months.

Some people may also develop Parkinson’s-type symptoms, such as slowness of movement, stiffness and tremor. In some cases, a person’s heart rate and blood pressure can also be affected.

‘'I'm also honest with Heather - if she tells me something that I've forgotten, I'll just say, "If you told me, I don't remember.’

What are the causes?

Lewy bodies are tiny protein deposits that develop inside some nerve cells in the brain, causing these cells to die. The loss of these cells causes dementia. It’s not yet understood why Lewy bodies occur in the brain and how they cause this damage.

Dementia with Lewy bodies shares similarities with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s dementia, although it is usually more aggressive than Parkinson’s dementia. It is progressive, so the symptoms will get worse over time.

Treating dementia with Lewy bodies

There isn’t a cure or specific treatment for dementia with Lewy bodies at the moment, but there are medications that some people may find effective. These may include dementia medications and Parkinson’s medications.

Some people may respond well to Parkinson’s medication, especially if they have Parkinson’s-like symptoms such as stiffness or rigidity. However, some side effects of these drugs can make the symptoms of dementia worse, especially confusion.

Using medication to treat dementia can be helpful. But it’s also useful for people to get treatment from a wide range of healthcare professionals, such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dietitians and speech and language therapists. They can help the person with dementia and those supporting them.

3.12 Caring for someone with Parkinson’s dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies

Practical advice

If you are caring for someone with any form of dementia, there are some practical things you can do that can help reduce their agitation or confusion and make life a bit easier:

- Keep to a daily routine as much as you can to help them remember when certain things like mealtimes will happen.

- Try to use familiar objects and phrases.

- Avoid unfamiliar environments – these can be quite stressful.

- Encourage someone with dementia to keep engaging and interacting with people. Hobbies are also a great way to keep memory and thinking as active as possible.

Find out more in the Parkinson’s UK dementia with Lewy bodies information sheet and the Parkinson’s dementia information sheet

3.13 Hallucinations and delusions

Some people with Parkinson’s have hallucinations, where they see, hear, feel or smell things that aren’t there. Some may have delusions, which are unusual thoughts, beliefs or worries that aren’t based on reality. These can include feelings of paranoia, jealousy or extravagance.

Side effects from Parkinson’s medication, the long-term use of this medication and other medical problems, such as infections, may be the cause of these cognitive problems.

Keep this in mind because it is important to not always assume that a person’s condition is simply getting worse. Symptoms caused by medication or infections can be treated effectively.

Advice should be sought from a specialist or Parkinson’s nurse.

Research shows that experiencing hallucinations or delusions can have a big effect on the quality of life of people with Parkinson’s. Research also shows that hallucinations and delusions often happen when someone with Parkinson’s has problems with memory or thinking, dementia, depression, sleep problems or very strong Parkinson’s movement symptoms.

Hallucinations can affect both younger and older people in the earlier stages of the condition, but are more common in people who have had Parkinson’s for a long time. They can be a side effect of Parkinson’s medication, but not everyone who takes Parkinson’s drugs will experience hallucinations. It depends on the exact type of medication, the dose and the person taking them. Sometimes, the higher the dose of medication, the more chance there is of experiencing hallucinations.

What is a hallucination?

A hallucination is when a person sees, hears, feels, smells or even tastes something that doesn’t exist. Hallucinations can affect all of the senses, not just sight.

If your client has hallucinations they may find them quite frightening. Some people will be aware that they are hallucinating, but some won’t be. How hallucinations affect someone will depend on how bad their experiences are, how other people around them respond and whether they have other mental health issues.

‘My hallucinations always featured people, and random people at that, so it was quite terrifying’

What are illusions?

Illusions happen when people see things in a different way from how they look in real life. For example, a coat hanging on a door might look like a person.

What are delusions?

While illusions and hallucinations are seeing, hearing, feeling and tasting things that don’t exist, delusions are thoughts or beliefs that aren’t based on reality. Even though they’re irrational, the person experiencing them may be convinced they’re true. This can be one of the most difficult symptoms to come to terms with, especially if they have delusions about their carer or someone close to them.

Delusions can include paranoia, jealousy or extravagance (believing you have special powers). They could make your client suspicious or mistrust others, anxious or irritable. Some people with Parkinson’s experience a mixture of hallucinations, illusions and delusions.

Treating hallucinations and delusions

If a person with Parkinson’s experiences hallucinations or delusions, it is important that medical advice is sought from their GP, specialist or Parkinson’s nurse. There may be other causes for these symptoms that may be treated effectively, such as fever from a chest or bladder infection.

Actions to take

- If the person is in an unfamiliar place (such as respite), try to make them feel as comfortable as possible. It may help to have familiar objects around them, such as family photographs.

- Encourage the person to keep engaging and interacting with other people.

- Take care with communication. Use familiar phrases, speak clearly, listen well and give the person time to respond to you.

- If the person does have an infection, it must be treated early with antibiotics.

- The person’s specialist or Parkinson’s nurse can change their drug treatment to make symptoms better. Some people will be taking medication (anticholinesterases) for dementia.

- Many people won’t tell you when hallucinations or delusions happen, so ask if you suspect they are experiencing these symptoms. Again, their specialist or Parkinson’s nurse may be able to adjust medication to ease symptoms.

- Where appropriate, a mental health referral may be required.

3.14 Exercise

Exercise 3.4

We have explored the cognitive difficulties that can result from Parkinson’s and how we can manage them. Think of a time when you were caring for a person with cognitive difficulties and use your reflection log to answer the following questions.

- What symptoms did the person have?

- What challenges did this give you as a carer?

- How did you manage these challenges?

- Was that successful?

- From what you have learned so far on the course, would you do anything differently now?

3.15 Summary

We have now looked in detail at the communication difficulties people with Parkinson’s could have, the impact of these and how they can be managed. We have also looked at the cognitive problems caused by Parkinson’s and how to care for people with these. Hopefully you have considered how this information can help you improve your practice and increase, where appropriate, the involvement of other health and social care professionals.

Now try the Section 3 quiz.

This is the third of the four section quizzes. As in the previous sections, you will need to try all the questions and complete the quiz if you wish to gain a digital badge. Working through the quiz is a valuable way of reinforcing what you’ve learned in this section. As you try the questions you will probably want to look back and review parts of the text and the activities that you’ve undertaken and recorded in your reflection log.

Personal reflection

At the end of each section you will be given time to reflect on the learning you have just completed and what that means for your practice. The following questions may help your reflection process.

Remember this is your view of your learning, not a test. No one else will look at what you have written. You can write as much or as little as you want.

Use your reflection log to answer the following questions.

- What did I find helpful about the section? Why?

- What did I find unhelpful or difficult? Why?

- What are the three main learning points for me from Section 3?

- How will these help me in my practice?

- What changes will I make to my practice from my learning in Section 3?

- What further reading or research do I want to do before the next section?

If you have the opportunity to be part of a study group, you may want to share some of your reflections with your colleagues.

Now that you’ve completed this section of the course, please move on to Section 4.

Glossary

- bradyphrenia

- Slowness of thought.

- deep brain stimulation

- A form of surgery that is used to treat some of the symptoms of Parkinson's.

- delusions

- When a person has thoughts and beliefs that aren’t based on reality.

- dyskinesia

- Involuntary movements, often a side effect of taking Parkinson’s medication for a long period of time.

- freezing

- A symptom of Parkinson’s where someone will stop suddenly while walking or when starting a movement.

- hallucinations

- When a person sees, hears, feels, smells or even tastes something that doesn’t exist.

- hypomimia

- The loss of facial expression caused by difficulty controlling facial muscles.

- Lewy bodies

- Protein deposits that develop inside some nerve cells in the brain, causing the cells to die. This loss leads to dementia with Lewy bodies.

- motor symptoms

- Symptoms that interrupt the ability to complete learned sequences of movements.

- non-motor symptoms

- Symptoms associated with Parkinson’s that aren’t associated with movement difficulties.

- ‘on/off’

- If a person's symptoms are well controlled, this is known as the 'on' period, which means that medication is working well. When symptoms return, this is known as the 'off' period. This might mean that a person who is out for a walk would suddenly be unable to continue walking, or when seated would feel unable to get up to answer the door. 'Off' periods usually come on gradually, but occasionally can be more sudden. When they come on suddenly, some people have compared this 'on/off' effect to that of a light switch being turned on and off.

- wearing off

- This is where a Parkinson’s drug becomes less effective before it is time for a person’s next dose. This may cause them to go ‘off’.