Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:26 PM

3 Using open educational resources

3.1 Introduction

This section of the course focuses on where you can find open resources, what factors might influence your choice, how to attribute a resource and the importance of how you remix to provide the best possible experience for learners.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course you should be able to:

- find relevant open resources suitable for your own context

- understand how to attribute a resource correctly

- have a better understanding of best practice for integrating open resources.

3.2 Where can I find OER?

Open educational resources (OER) can be found in many places, but it is not always immediately obvious where to find material that gives you explicit permission to reuse it or how to find the most relevant material for your context. Some of the more familiar places to find resources, such as Flickr, YouTube or Google, include filters so that you can show only openly licensed images or videos.

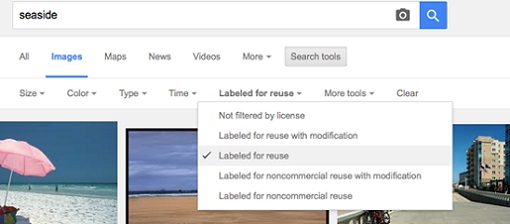

For example, when you are searching for an image on Google you can choose to see images with specific types of permissions for their reuse. To do this, once you have searched for a particular image, go to the ‘Search tools’ tab and choose ‘Labeled for reuse’ before selecting what type of licence you would like to see.

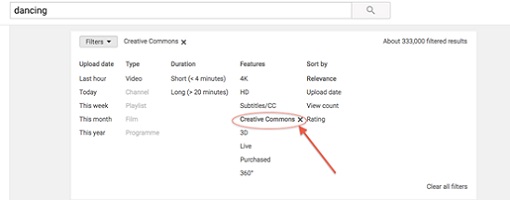

There are two ways to find openly licensed videos on YouTube. When searching for videos you can choose to add a range of different ‘filters’, and this includes ‘Creative Commons’ as a ‘Feature’ of the type of video you are seeking.

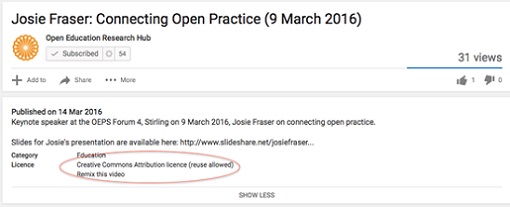

However, you can also see what kind of licence an individual video carries. As you can tell from the licensing information provided in Figure 3, this video is available for reuse can be edited and remixed on YouTube.

You can find more detailed instructions on how to find OER on Google and YouTube and other platforms in this presentation by the ROER4D project: ‘How and where to find OER’ or by looking at Glasgow Caledonian University’s guide to finding Creative Commons licensed images.

There are also specific repositories that only contain OER. Whilst JORUM, the UK-based repository for sharing OER across all sectors is no longer maintained, other collections are available, such as the College Development Network’s site. OpenCNX (formerly Connexions) is a repository of OER where learners and educators can share and remix materials. The OER Quality project has created and crowdsourced a list of repositories around the world, and members of their project have been involved in creating a map of repositories.

You could also explore searchable and curated spaces offered by OER Commons or the European Commission’s Open Education Europa portal.

Sometimes it can be difficult to find the resource you need for your own learning, or to help others. In the instance of OpenLearn, The Open University’s OER repository teams in Scotland and Wales have created themed ‘learning pathways’ to help learners navigate their way through materials, develop their interest in a particular area and build their confidence, whilst introducing them to higher education (HE) study. You can read more about how the Pathways programme was developed in Scotland and Wales. Helping learners navigate their way through materials is an important factor in enabling effective learning, and Section 3.5 on curation will look at this in more depth.

Activity 3A

Think of a situation where you need to use an image created by others. Use an appropriate site such as Flickr or the search tool on the OEPS hub etc. to find a relevant openly licensed image.

Write down in your reflective log a brief description of the situation, the resource’s URL, what licence it has and explain why the open licence works within your context and the purpose you intended to use it for.

3.3 Choosing a resource

The last section gave suggestions for how and where to find content. If you are facilitating learning, looking for inspiration, putting together a reading list, encouraging learners to engage in independent study, rewriting a course or simply looking for inspiration, these factors will influence your choice. You will also be thinking about the type of learners you have, their context and desired learning outcomes.

In addition to sites such as YouTube, that offer both openly licensed and non-openly licensed materials, some websites offer openly available materials that are not openly licensed. For example, the BBC-hosted website BBC Learning has lots of useful resources, and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) from providers such as FutureLearn or MITx provide whole courses that might be useful and which anyone can sign up to. As resources from these sites are not necessarily openly licensed, you will need to check before reusing them.

When you are choosing an open resource, quality might initially be a concern. MOOC platforms and curated content sites are often part of an organisation’s public engagement strategy, and institutions ensure that their courses are developed in accordance with defined quality criteria. Examples include The Open University’s OpenLearn, The University of Edinburgh’s OpenEd and The University of Nottingham’s U Now. These can be good places to start looking for open content. To help other users and provide feedback to the resource’s creator, some platforms enable you to ‘rate’ a resource or comment on it.

Yet what does ‘quality’ mean to you when you’re planning to adapt something to your own context? As David Wiley argues in his post ‘Stop saying “high quality”’, references to quality when discussing OER often ignore the critical point that:

‘…the core issue in determining the quality of any educational resource is the degree to which it supports learning.’

In other words, your choice of a resource will take into account the needs of the learners and relevance to the objectives of the activity, course or learning journey.

Activity 3B

Use your reflective log to list the most important factors for you in choosing an educational resource. What would you describe as a ‘quality’ resource? For example, do you look for resources that have been reviewed positively by others, explain ideas clearly or do you look for material with additional resources, such as a lesson plan or associated activities, etc?

3.4 Attributing a resource

In Section 3.2 you searched for openly licensed materials that you might want to incorporate or use in your everyday practice. You also identified the resource’s licence and what this means for how you can reuse the resource. The next stage is to look at how to attribute the resource when you are reusing it within your own context. This is good practice for two reasons: not only to ensure that you have appropriately accredited the authorship and licence of the original material, but also so that people using or reviewing the resource you have created are able to reuse the material in their own context.

A quick and easy way to remember what information you need to include when reusing resources is by remembering an acronym: TASL. This stands for Title, Author, Source, Licence. TASL tells you what you need to include to ensure that you are appropriately acknowledging the source of the OER that you are using.

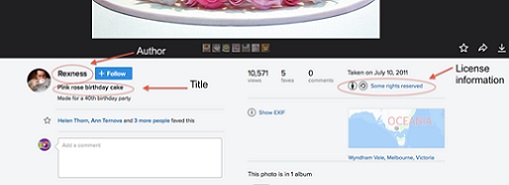

Let’s illustrate this with an example. If you follow this link to Flickr you can find the above picture of a cake, which was found using a Google search and filtering images for ‘labeled for reuse’ (see Section 3.2 for more on how to do this), and has been uploaded to Flickr by its creator. How will we correctly license this resource using TASL?

First, what is the resource’s title? In this instance it is labeled as ‘Pink rose birthday cake.’ So that others can see the origin of the resource we also need to provide the URL (https://www.flickr.com/ photos/ rexness/ 5920122416/ in/ gallery-123856341) of the page on Flickr where the image is hosted.

Who created the resource? The author or creator of the cake photo is Rexness. We can view Rexness’s Flickr profile by clicking on his name and clicking on the dropdown menu labeled ‘More’ on the right-hand side of the page and choosing ‘Profile’. This reveals further information about Rexness and we will use this URL as part of our attribution.

What is the source of the resource? In this instance the source of the image is the same as the URL we are using for the resource’s title.

What licence does the image have? To see an image’s licence information on Flickr, click on the ‘Some rights reserved’ text below the date the image was created. This reveals that the image ‘Pink rose birthday cake’ has been licensed CC BY-SA 2.0 by Rexness. We are also redirected to Creative Commons licence information automatically. This is the URL we need to include so that others can find out the correct licence information.

So what does the final attribution look like?

‘Pink rose birthday cake’ by Rexness is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

For further advice on attribution, consult the Creative Commons Wiki guidelines on best practice for attribution and Glasgow Caledonian University's guide to Reusing Content for more advice and examples.

When you decide to use an open resource that someone has provided, it is also good practice, where possible, to let the creator of the resource know how you have reused it (for example via the comments section on the relevant webpage etc.). In instances where the author has listed the licence but not explicitly linked to the relevant licence deed, you should provide an explicit link to the licence when reusing.

One issue for creators of OER is how to measure the impact of the resources they openly license: once ‘in the wild’ or freely available, it is extremely difficult to track how and in what contexts they are reused. You can read more about tracking the impact of resources in Section 4.6.

Activity 3C

Use the guidelines above and previous sections’ suggestions to help with the following activity.

In Section 3.2 you looked at finding resources you might want to incorporate into your own practice and considered whether the way they were licensed was most appropriate for your own context. Use the acronym TASL to help attribute the resource that you found earlier, or choose a different one if you’d prefer. Write down the attribution and licence information in your reflective log.

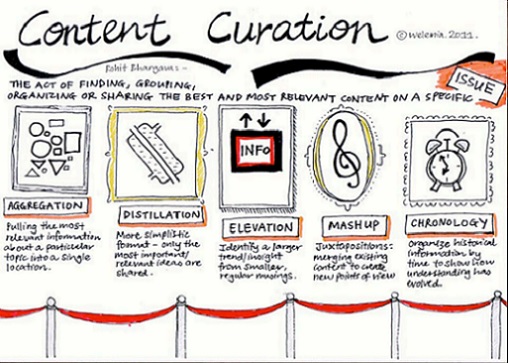

3.5 Curating OER

The notion of the teacher or facilitator as curator is helpful when working with open and online resources (Siemens, 2007) and reflects the possibility of education moving away from the ‘transmission’ of knowledge from teacher to learner, to a more constructivist approach which acknowledges the value of education created by the learner. Earlier in this section of the course we focused on one aspect of the curation process: choosing OER and what factors are important to you when selecting resources.

When using OER it is important to consider how you will integrate material into the learning process, particularly if you are blending together material that has been used in different situations (e.g. online or face-to-face). You will need a clear structure with guidance on outcomes, sequencing and, (where appropriate), you might want to consider including opportunities to collaborate with fellow learners. For example, providing your learners with a set of URLs to useful resources, however relevant and interesting, will not necessarily give sufficient context or information on why the learner should read further. You might want to consider introducing peer support (again, where appropriate), and study groups might be one option for bringing people together to discuss course materials.

Even if your learners are confident and have advanced digital literacy skills, without the OER being integrated into a broader framework or by providing support to navigate materials, it might be difficult to follow and engage with the content as a whole. Ensuring that any open resources you choose to utilise are smoothly mixed together is an important element of good open educational practice. In addition, you might want to encourage students to create OER as part of their studies (see Section 2.5) or work with students to rewrite course material or textbooks. As Natalie Lafferty of Dundee University noted in an interview published in February 2016, if you plan to incorporate learning activities that involve students in creating digital assets, it’s important to ensure that there is appropriate advice, information and support to get started. The next section of the course will take a closer look at curation as ‘remix.’

Activity 3D

Take a few minutes to review your reflective log. In light of what you’ve learnt so far in the course, consider if you want to develop the ideas you’ve noted for developing your practice any further. If so, add your new ideas and thoughts, as appropriate.

Now try the Section 3 quiz to consolidate your knowledge and understanding from this section. Completing the quizzes is part of gaining the statement of participation and/or the digital badge, as explained in the Course and badge information.

3.6 If you want to know more ...

Each If you want to know more … section of the course thematically presents additional material and resources on the topics for that section of the course.

Understanding open practices and open educational resources

The DigiLit project at Leicester City Council in the UK has produced a series of guides to help educators, particularly those teaching in the compulsory education sector, to understand and use OER. These include G1 Open Education and the Schools Sector and G2 Understanding Open Licensing for more information on open licensing and what OER is.

If you’d like to spend a bit more time looking at Creative Commons licensing and how to use them, you can participate in a free open online course at Peer 2 Peer University (P2PU) called Get CC Savvy. P2PU also run courses called Open Detective and Intro to Openness in Education that will help you understand different types of openly licensed material.

If you’re interested in looking in more detail at different licence types (including those for open source software), it’s worth looking at this comparison of free and open-source software licences or reading more about open source licensing.

To find out more about connectivism, read George Siemen’s ‘Connectivism – a learning theory for the digital age’ (2005) or watch ‘10 minute lecture – George Siemens – curational teaching’.

Using open educational resources

Here are some more ideas for where to look for openly licensed resources:

- JiSC’s Digital Media Guide, ‘Finding video, audio and images online’.

- An Open Education Working Group blog post ‘Illustrating open education’ (by Marieke Guy) has a useful list of places to look for openly licensed content.

- You can search for OER by subject or look at specific subject repositories. The Royal Geographical Society highlights a number of sources for OER in geography, for example.

- Read more about how the OER Assistant is helping educators find OER according to learning objectives.

There are some useful guides to developing online teaching and learning available, including:

- ORBIT: The Open Resource Bank for Interactive Teaching.

- University of Leicester’s ‘Writing and structuring online learning materials’.

Now go to Section 4 of the course.