Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 11:05 PM

2 Why use open practices and resources?

2.1 Introduction

This section of the course focuses on the reasons why you should use open educational resources (OERs) or develop ‘open’ practices within your context. You’ll take a closer look at what the ‘open’ aspect of open licensing means and how this impacts on finding and attributing openly licensed materials. You’ll also look at why you might use open educational practices (OEPs) and openly license your own material. This section closes with a look at digital literacy within the context of open educational practices (OEPs) and open educational resources (OERs).

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course you should be able to:

- understand some of the reasons why you might use open educational resources (OERs) for teaching and learning

- explore reasons why you might want to openly license your own material and what the challenges might be

- understand the importance of digital literacy in relation to openness

- explore the meaning of ‘open’ in open licensing in more detail.

2.2 The meaning of ‘open’ in open licensing

Before looking at some of the reasons you might want to use open educational resources (OERs) or adopt more ‘open’ practices, let’s pause briefly and take another closer look at the concept of ‘open’ within the context of (re)using OER. Copyright is primarily concerned with what you cannot do with material and restrictions on its use, whereas an open licence offers the possibility of reuse and remixing without having to seek the creator’s permission or needing to pay a fee for using the material.

Section 1 of the course revealed the variety of characteristics usually associated with ‘openness’ and how people define ‘open’ in different ways. Moreover, in addition to the diversity of contexts that could be described as ‘open’ there are not just open or closed practices, but many different shades of open behaviours or practice: what is described as a ‘continuum of openness’.

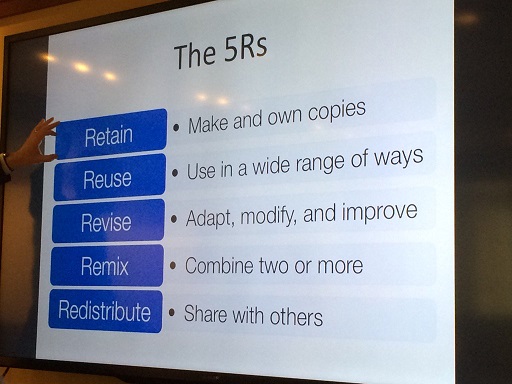

Section 1.3 introduced one definition that is commonly referred to when exploring the idea of ‘openness’ within the context of the use and creation of OER: the ‘5 Rs’ that David Wiley, a well-known advocate of open education, has developed (see Figure 2.1). The 5 Rs highlight the benefits and freedoms, rather than restrictions in place, on a resource with an open licence:

- Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content.

- Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g. in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video).

- Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g. translate the content into another language).

- Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other open content to create something new (e.g. incorporate the content into a mashup).

- Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g. give a copy of the content to a friend).

According to Wiley and this ‘rights’-based framework for understanding what an open licence enables you to do, if a resource fulfils all these criteria and therefore is explicit in giving you the ‘right’ to remix, retain, reuse, revise and redistribute a resource, then it can be described as an open educational resource (OER). By and large, open licences are used to convey relevant information associated with the 5Rs: this is because open licences such as Creative Commons act as a shorthand to giving permission for reuse, are widely used and easily understood.

As can be inferred from some of the Rs listed above, openness in this context also involves changes to the way you might approach or create material, or collaborate with others. For example, with an OER you are able to circulate or use copies of material without seeking the author’s permission to do so. You can also develop new material based on existing open content under the permissions granted by the original author. In both instances, because an OER should clearly state the reuse criteria, you can save time and money, as you do not need to wait for author permission to reuse a resource and you don’t need to spend time creating your own resource from scratch when someone else has already created something you can reuse or modify for your own purposes.

Creating new resources with OER might enable collaborative experimentation with colleagues, highlight the benefit of sharing resources and good practice, enable iterative improvement to resources, or even highlight social justice by opening up new opportunities for those not currently engaged in, or distanced from, formal education. One example of using open resources to engage with the wider community is Strathclyde University’s widening participation strategy, which ‘aims to remove barriers for under-represented groups to get to university’. More on how this was developed is discussed on the OEPS hub.

However, it's not just about your ‘right’ to do certain things with material that is openly licensed. Implicit in the idea of the 5Rs and in order for the ‘right’ to remix, reuse, redistribute, revise and retain to be possible, you also need to enable others to do the same (so they have the same ‘rights’ as you) by sharing back your remixed material or original content (in other words, facilitating the ‘virtuous circle’ noted earlier in Section 1.4: The practice of open educational resources).

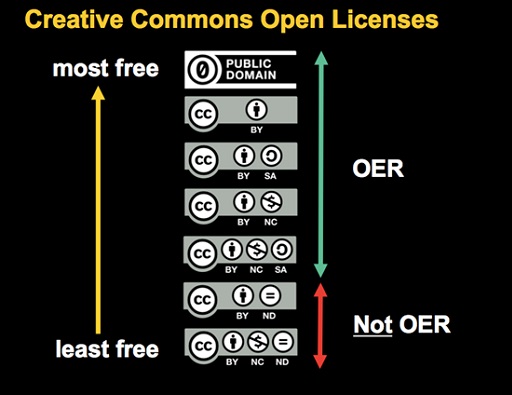

One component of this is the licence. As described in Section 1.5 there are different types of licences giving different types of permissions for reuse. These different licences can be understood as a ‘continuum of openness’, as some are more liberal in their reuse permissions than others. Figure 2.2 below shows licences placed along a scale of ‘least free’ to ‘most free’ and correspondingly ‘not OER’ to ‘OER’ (note ‘free’ is understood as ‘libre’ within this context, see Section 1.2 for further explanation.)

If you need reminding of the licence types, check out Creative Commons.

As you can see from Figure 2.2, there are some Creative Commons licensed resources that are not considered to be OER and are described as the ‘least free’ of the open licences (the CC-BY-ND and CC-BY-SA-NC licences). This is because these licences include ‘ND’ or the ‘no-derivatives’ instruction. In other words, when using the resource it can only be used ‘as is’ and not modified in any way. This prohibits any adjustment, changes or building on the resource, either so that it reflects better your own context(s) or to combine it with other OER or materials you have created. Therefore, the ND licence fails to fulfil the ‘revise’ and ‘remix’ criteria of Wiley’s 5Rs.

There are arguments for and against using different types of Creative Commons licences, in particular the NC or ‘non-commercial’ licence. In the instance of NC-licensed materials, some people argue that prohibiting commercial use of resources can stifle innovation. US educator and co-author of the open textbook Introductory Statistics, Barbara Illowsky, explains why their textbook is CC-BY:

I wanted to talk about commercial aspects... So one of the interesting comments we have, is how could you not put the NC on your licencse, how could you agree to a CC-BY because somebody else can take your work and make money. That’s true, but if we didn’t put that BY on there, there wouldn’t be other innovations. So, for example, another college... their bookstore wouldn’t be able to sell the book because they earn a profit on the hard copy of it. WebAssign... Collaborative Statistics was the first Open Ed Resource that they hooked up with to do a homework system with. Before they were working only with major publishers. But when I was starting to present at national conferences, and faculty said I love this book but I would never adopt it because I don’t want to go back to grading homework... The trade-off of a student spending $200 for a book that comes with a homework grading system, or me having to grade homework, they are going to buy the book.

So I approached WebAssign – it’s a fabulous company – but it does cost the students $25. So I tell the students, I recommend it but you don’t have to buy it. If you want to turn in the hard copy paper with your problems worked out to me you can, but I think that the WebAssign has a learning system that goes along with it, they have the videos integrated, they have the books integrated... if you get stuck on a homework problem, it takes you back to the book if you want [etc.]... So I think this is a valuable learning tool, not just making my life easier for grading … now I’ve only had two students who started out turning in a hard copy paper and they eventually ended up buying it. So that’s a company that is doing innovation, but if I had the NC license on it, they wouldn’t.

A more in-depth exploration of the NC licence is also available here.

Many national or international organisations that support the use of openly licensed materials argue for the use of the CC-BY licence; for example the Wellcome Trust, as this type of licence gives ‘much greater use – and therefore impact – of the research we fund and the content we produce.’

Later in the course you will look at developing your own resources and return to look at David Wiley’s 5Rs to help you understand what you need to do to enable others to easily find, use, remix and adapt resources you choose to share.

Activity 2A

This section has explored shades of openness within educational resources that are described as ‘open’ or OER. However, the idea of ‘open’ is also applicable to other contexts, including everyday practice.

Think about your own context and use your reflective log to write down:

- Examples of practices that could be considered ‘open’.

- Instances where it might not be appropriate to be open.

2.3 Why use open educational resources (OER)?

There are many reasons why people deliberately look for open resources when searching for materials. Resources with open licences can provide valuable and interesting additional or primary teaching materials, or the basis for a workshop or study group, at low- or no-cost. Within a variety of situations OER can provide content where there was none previously available or replace expensive proprietary material (for example textbooks, where cost savings can be an important motivating factor in OER adoption).

OER can be utilised at short notice and do not require payment or permission for their use. Open materials can often be modified to suit your specific context, so you can create unique resources based on others’ expertise. Some OER are produced by well-known institutions or shared by educators who are experts in their subject. In addition, resources are often peer-reviewed by others online or during their production process, when OER are produced at scale (as in the instance of open textbooks, see OpenStax College for one example).

Whilst the outcomes of using OER are important motivators for their use, there are also potential impacts on educator practice. Some of the possible changes in practice are implicit in in this summary on reasons for using OER produced by Glasgow Caledonian University:

- ‘You can take existing resources and develop them in ways that suit your needs.

- You can develop high quality resources on your own or with a small team of staff.

- You can save time and duplication of effort.

- You can build on best practice by experts in your subject area.

- You can use resources which you may not have the software, equipment or facilities to create yourself.’

Research conducted by the OER Research Hub on the impact of OER found that educators are better able to accommodate diverse student needs and can be more experimental in their teaching approaches. They are not restricted to using specific resources and can develop their own materials from existing resources or find resources that they are not able to create themselves or which have interesting ways of conveying points. Open resources might provide inspiration and ideas when developing one’s own resources or expose one to different practices or approaches.

Using OER and engaging in more open practices can yield a range of institutional benefits. A JISC-funded study supplemental Good Intentions by McGill, Currier, Duncan and Douglas (2008) maps a range of stakeholder aims against different ‘sharing’ strategies, including an ‘open’ option. The open approach was described as having the potential to have ‘significant impact’ on nine out of a possible 15 ‘benefits for educational institutions’ (with ‘possible’ or ‘some’ impact possible in the remaining six areas):

- ‘Maintaining & building on institutional reputation globally

- Attracting new staff and students to institution – recruitment tool for students and prospective employer partners

- Increased transparency and quality of learning materials

- Shares expertise efficiently within institutions

- Encourages high-quality learning & teaching resources

- Supports modular course development

- Supports the altruistic notion that sharing knowledge is in line with academic traditions and a good thing to do

- Likely to encourage review of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment

- Enhancing connections with external stakeholders by making resources visible.’

‘Openness’ therefore has the potential to raise standards, increase engagement and widen participation. For example, OER Hub collaborative research revealed that 32 per cent of learners using The Open University’s OpenLearn platform felt that their use of OER on the site influenced their decision to register for their current course of study (N=934). Research by Wiley, Hilton III, Ellington & Hall (2012) revealed that implementing the use of open resources according to the ‘successful model’ they developed as part of their two-year research study, can offer institutions significant savings when compared with the use of proprietary materials.

Open and Public Domain resources enable you to reuse materials without asking permission as long as you attribute their source and the type of licence the resource carries. OER can also change your practice by enabling you to access and rework materials, experiment with them and tailor them to your needs.

However, there are also possible questions and concerns regarding OER use. OER Mythbusting by the OER Policy for Europe project addresses the main concerns, including the quality of resources, compatibility with the curriculum, sustainability and time.

Activity 2B

Read two of David Wiley’s blog posts, ‘Evolving “open pedagogy”’ and ‘The real threat of OER’, which look at unravelling open practice within the context of teaching and the reasons educators use OER, respectively. As David notes at the start of ‘Evolving…’ the key question to consider is:

‘What can I do in the context of open that I couldn’t do before?’

Now that you have read David’s posts, look back at your reflective log notes from earlier in the course, review your notes on how and why you share and what kinds of practices you consider to be ‘open’. Now consider the following questions:

- What does or could openness facilitate in the contexts you work in?

- How could you incorporate more open material or practices?

Write down your responses in your reflective log.

2.4 Why openly license my own materials?

The last section explored some of the reasons to seek out and utilise OER. However, in order to facilitate 'open' best practice it is also good to share material you have created too (and therefore complete the ‘virtuous circle’ mentioned in Section 1.4). After all, materials can’t really be called ‘open’ unless they are both shared and when they’re being created they are made as reuseable as possible (e.g. by providing creator information and details of how you would like them to be reused).

There are many reasons for sharing materials. By releasing material on an open licence you might increase the visibility and reputation of your work, find new audiences and networks, or receive increased feedback on what you are doing. Often people are altruistically motivated and become involved in different open practices such as openly licensing their own materials and sharing their resources in order to ‘open up’ or increase participation or widen access to otherwise closed environments and information. By widening access to information, knowledge can be shared more effectively, particularly with people who might otherwise be unable to access materials (e.g. for reasons such as cost or geography).

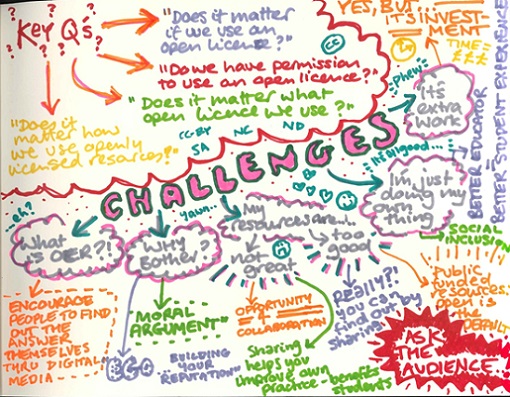

When thinking about whether or not to openly license your work, you might have some reservations. For example:

- Do I have the skills or knowledge to license my material?

- If I blog about my research might someone steal my ideas?

- Are my resources good enough?

- What will my colleagues and students think?

- Am I allowed to release my teaching materials on an open licence?

- Do I have the technical and digital skills to create OER?

The sketch note above (which was produced as part of a visual recording of Josie Fraser’s keynote at OEPS Forum 4) shows the results of an ‘ask the audience’ exercise. Josie asked the audience to respond to commonly heard reasons educators give for not using or sharing materials in the open.

Activity 2C

Some of the challenges noted above may resonate with you, or you may have heard of some from colleagues. Pause for a moment and write down any thoughts or responses to these, or note down any questions you’ve heard that are not on the list or in the sketch note above, in your reflective log.

Whilst using or incorporating OER into your own practice might not always be visible or impact on others in an obvious way, becoming more open in your practice and sharing your material or resources openly may lead to unanticipated changes to your current practice. You might develop different working strategies, take a different approach to designing the materials themselves or collaborate differently with colleagues if you choose to co-develop openly licensed materials. Letting colleagues and students know that you are using an open resource and explaining what it means can also raise awareness and open up discussions around ‘open’.

Your own, your institution and/or organisation’s approaches to sharing and openness will also have an impact on how you move toward more open ways of practice. Experimenting with releasing images you have created in your own time (for example, holiday photos) openly on Flickr is a great place to start. Depending on your institution’s approach and view of open practices, openly licensing your course materials or resources created in work time might be a more complex matter, particularly in relation to intellectual property and ownership of the resource. To resolve copyright issues, some Scottish Universities, including the University of Edinburgh and Glasgow Caledonian University, have introduced policies to encourage their students and educators to release material in the open.

Activity 2D

Reflect on your own institution or organisation and using your reflective log, write down your responses to the following questions:

- Would it be appropriate to share outputs or resources you have created on an open licence?

- In what ways, if any, does your institution or organisation support the use and creation of open resources?

- Is there a specific person or team you can ask for assistance? If so, note down their name(s) and details. If you are not sure whether there is any support available to you, you may want to check with colleagues or if you work in a college or university, with library staff.

- Does your institution or the organisation you work for have a policy on OER and/or OEP?

2.5 Digital literacies

Changes in how information is shared, whilst dependent on who has control of the mode and means of dissemination, can enable increased access to information. The development of the Internet, in tandem with increased access to, and development of, technology to access the web, has enabled people to find, share and exchange information beyond national boundaries. For example, European Commission research in early 2016 revealed that ‘95% of 16–24 year olds in the EU are regular Internet users’. With access to technology and the knowledge of where to find resources, open education has made materials more accessible and can potentially widen access and participation.

Yet could these ‘95% of "regular Internet users" ’ be described as digitally literate? In other words, do people have the confidence and knowledge to find, appraise and use the resources they find online? Although students and learners may be using the Internet, their levels of digital literacy are likely to differ. Subsequently, this may affect their ability to engage with the increasing amount of educational material that is now available and accessible online, and which can be accessed, reused and studied in both informal and formal contexts by people who may be studying or facilitating learning or just simply interested in finding out more about a particular topic. JISC’s (formerly the Joint Information Systems Committee) ‘quick guide’ ‘Developing students’ digital literacy’ provides a good overview of ‘next steps’ for thinking about developing learners’ digital literacies and the reasons why this is an important consideration. JISC also provides top tips for different groups of users and a wide range of resources to help understand and develop digital skills across institutions and organisations.

Digitisation can reduce individual transaction costs and enable information to be shared easily between interested parties, for example, paywalled research articles or downloaded materials are often shared, in spite of restrictions such as publisher agreements or the mechanism for sharing the material in the first place, e.g. virtual learning environments (VLEs). The possibility for learning outside an institution is potentially increased if one knows where to find materials and resources. There are even examples of people crafting their own curricula through OER and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs).

The channels by which students can find information have also increased. In addition to asking fellow students or their teacher, going to the library or using a hard copy encyclopedia or printed resources to find out information, learners today use search engines, most likely Google, or Wikipedia to find out more about a topic. Research by Head & Eisenberg (2010) conducted with US college students revealed ‘over half of the survey respondents (52 per cent) were frequent Wikipedia users [during their course] – even if an instructor advised against it’, with a further 22 per cent reporting using the open, crowdsourced encyclopedia ‘occasionally’.

The availability of information and learning resources can be seen as a challenge to, or conversely, an opportunity for, formal learning. After all, the two are not mutually exclusive. What if educators were to incorporate and use online platforms and materials into their lessons, or to encourage students to critically assess material on (rather than ban the use of) platforms such as Wikipedia, share and develop ideas online and utilise YouTube, Twitter and other platforms? Rather than prohibiting the use of resources such as Wikipedia, there is arguably the opportunity to develop learners’ digital literacy skills as part of embracing openness in education.

For an example of how an educator helped to develop learners’ digital literacy skills read how Natalie Lafferty, Head of the Centre for Technology and Innovation in Learning at Dundee University enabled students to become co-creators of OER.

Activity 2E

Think about the learners you work with.

- What level of familiarity with technology do they have?

- What kinds of digital skills do they have?

- How could what you do in the classroom, at a workshop or elsewhere help recognise and develop the skills your students have?

Write down your thoughts and strategies in your reflective log. You might also want to consider sharing ideas and any strategies that you’ve found effective on the OEPS Forum.

Now try the Section 2 quiz to consolidate your knowledge and understanding from this section. Completing the quizzes is part of gaining the statement of participation and/or the digital badge, as explained in the Course and badge information.

2.6 If you want to know more ...

Each If you want to know more ... section of the course thematically presents additional material and resources on the topics for that section of the course.

The ‘open’ in open licensing

If you’re interested in exploring the ‘continuum of openness’ and what this means in practical terms, read Hilton III, Wiley, Stein & Johnson’s The Four R’s of Openness and ALMS Analysis: Frameworks for Open Educational Resources.

Benefits and challenges of open educational resources

If you’re interested in taking a closer look at the wide range of reasons for using OER or engaging in OEP, there is a range of research available, including the UKOER Synthesis & Evaluation report, which has a section on motivations. This section of the report explores the idea that reasons for engaging in OEP/OER can be categorised by stakeholder group. The OER Impact Study: Research Report by Liz Masterman and Joanna Wild looks at reasons for using OER within the UK’s HE sector.

Take a closer look at some of the benefits and challenges of OER in this series of posts:

- ‘Benefits and challenges of OER for higher education institutions’ (Cheryl Hodgkinson-Williams).

- ‘The financial benefits of OER’ (Rob Farrow).

- Watch ‘Open education matters: why is it important to share content?’

- The OER Research Hub has researched some of the challenges for people using OER. Read their 2013–2014 report.

If you’re interested in the potential issues with regard to sharing openly licensed resources, these posts might be of interest:

OER policies

Leeds University’s OER policy (which has been used as a basis for, or reviewed, by other institutions such as Glasgow Caledonian University and the University of Edinburgh as part of their own development of an OER policy) and The Open University (UK)’s open educational media operating policy are useful to review.

Digital literacy

Read ‘Focus on data literacies and ICT proficiency: the importance of digital capabilities’, which highlights the need for ‘training and support’ in preventing incidents such as that which occurred in September 2015, when a London clinic accidentally released via email personal information of HIV positive patients and other patients visiting an HIV drop-in facility.

In ‘The death of the digital native: four provocations from Digifest speaker, Donna Lanclos’, the author begins her provocations by arguing that it’s a ‘dangerous assumption’ to consider learners inherently digitally savvy.

If you are interested in improving your digital literacy skills, you can participate in the badged OpenLearn course Succeeding in a digital world.

Now go to Section 3 of the course.