Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 11 March 2026, 2:22 AM

Communicable Diseases Module: 13. Introduction, Transmission and Tuberculosis Case Finding

Study Session 13 Introduction, Transmission and Tuberculosis Case Finding

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the major common diseases in Ethiopia and you are very likely to have come across this disease in your daily work as a health worker. In this study session, you will learn about the cause of TB, how important it is as a public health problem in the world, in Africa and in Ethiopia. You will also come to understand how TB is transmitted (spread) in the community. This study session will also help you to understand the approach adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) to tackle the problem of TB worldwide.

You will become aware of what you and other health workers can do, in line with the global plan, to reduce and eliminate the problem of TB in your community. You will also learn how to identify a suspected case of TB and how to confirm your suspicions by reaching a diagnosis. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of TB patients is essential if you are to help reduce the sufferings of patients and stop the spread of TB in your community.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 13

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

13.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 13.1, 13.2, 13.4 and 13.7)

13.2 Describe the burden of TB in the world, Africa and Ethiopia. (SAQs 13.2 and 13.3)

13.3 Describe the global approach to fight tuberculosis, known as the Global Stop TB Strategy. (SAQ 13.4)

13.4 Describe the mode of transmission of tuberculosis and identify the groups most at risk of TB infection. (SAQs 13.1 and 13.5)

13.5 Detect and confirm a case of TB based on clinical signs and screening of sputum specimens. (SAQs 13.6 and 13.7)

13.1 What is TB?

‘Pulmonary’ is the term given to anything affecting the lungs. ‘Extra-pulmonary’ means outside the lungs.

Tuberculosis is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis; another name for these bacteria is TB bacteria or tubercle bacilli. TB usually affects the lungs (80% of TB cases are of this type), hence the name pulmonary TB (PTB). When other organs of the body are affected, such as the bones, joints, lymph-nodes, gastro-intestinal tract, meninges (coverings of the brain), or the reproductive system, kidneys and bladder (also known as the genito-urinary tract), the disease is called extra-pulmonary TB (or EPTB).

You have probably come across people who suffer from TB. Do you know what the most common symptoms are?

If you have direct experience of TB patients, you will probably know the symptoms are: persistent cough, weight loss, chest pain, tiredness, difficulty in breathing, sometimes spitting up blood, and general symptoms like sweating and fever.

13.2 Global and regional burden of TB disease

TB is a major public health problem throughout the world. According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Report 2009, one-third of the world’s population is estimated to be infected with TB bacteria and at risk of developing the active form of the disease. In 2009, the annual incidence of TB (the number of new cases) across the world was about nine million people. The annual number of deaths due to TB was 1.7 million, including 195,000 patients infected with HIV. In developing countries, TB comprises 25% of all avoidable adult deaths. The disease affects both sexes equally and most TB cases are found among the age group 15–54 years. Since this group constitutes the majority of the working population, their deaths can be a major blow to the economy of any country.

Thirty percent (30%) of the estimated total TB cases in the world in 2008 occurred in Africa. Among African countries, South Africa has the highest estimated number of cases (0.38-0.57 million), followed by Nigeria (0.37-0.55 million), and Ethiopia is third with 0.24-0.36 million. Throughout the world, almost 30,000 cases of multidrug resistant-TB (MDR-TB), a form of TB that does not respond to the standard treatments using the drugs most commonly used against TB, were reported in 2008.

The main reasons for the increasing burden of TB globally include:

- Poverty.

- Neglect of the disease (inadequate case finding, diagnosis and cure).

- Collapse of the health system in countries experiencing severe economic crisis or civil unrest.

- Effect of the HIV pandemic.

TB is a disease of poverty because most cases occur among poor peoples of the world, often living in very poor conditions and hard-to-reach communities. Because of their circumstances, poor people do not have easy access to health care services, including diagnosis and treatment for TB. This is why your role as a Health Extension Practitioner is crucial, because you can bring TB diagnosis and treatment within reach of the rural community dwellers.

13.2.1 Tuberculosis burden in Ethiopia

According to the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health’s hospital data, tuberculosis is the leading cause of morbidity (sickness), the third cause of hospital admission, and the second cause of death in Ethiopia, after malaria.

Sputum is jelly-like mucus coughed up from the lungs. TB bacilli can be seen in sputum smeared thinly onto a glass microscope slide and stained with special dye.

Ethiopia ranks seventh among the 22 countries with high TB burden, and third only to South Africa and Nigeria in Africa, with an estimated incidence of all forms of TB at 378/100,000 in 2009. This means that among every 100,000 Ethiopians, 378 new cases of TB were estimated to have occurred in 2009. The estimated incidence of smear-positive (a form of TB in which TB bacteria are seen when a sputum smear is stained and examined under the microscope) is 163 per 100,000 population. If the population of Ethiopia is assumed to be 80,000,000, then 302,400 new cases of all forms of TB and 130,400 new smear-positive TB cases were expected to have occurred in the country in 2009. However, of the estimated figures, only 145,924 (48%) of all forms of TB cases and 44,593 (34%) of estimated new smear-positive TB cases were actually detected. This suggests that the number of TB cases detected in Ethiopia in 2009 is far below the expected numbers.

For all forms of TB the expected cases calculation is 80,000,000 divided by 100,000 = 800, then 800 x 378 = 302,400 cases. For smear-positive cases it is 80,000,000 divided by 100,000 = 800, then 800 x 163 = 130,400 cases.

The global target for TB control is to detect at least 70% of the smear-positive cases and cure at least 85% of the detected cases. If we do not detect TB cases as they occur in the communities, it means that people who are sick with active TB will continue to spread the disease among the healthy population and many people will continue to suffer and/or die in our communities.

As a Health Extension Practitioner, you have an important role to play in the community to prevent and control TB.

The HIV epidemic (which you will learn more about in Communicable Diseases, Part 3) has made the TB situation significantly worse by accelerating the progression of TB infection to active TB disease, thus increasing the number of new TB cases. Another challenge to TB control in Ethiopia is the emergence of MDR-TB, with 5,979 estimated cases in 2007.

13.3 Global strategy for the prevention and control of TB

In 1994, WHO launched their global strategy for the prevention and control of TB. The key feature of the strategy remains the Directly Observed Treatment, Short-course (DOTS), as the best approach to TB. DOTS has five key components:

- Sustained government political and financial commitment to TB control

- Access to quality-assured laboratories for the confirmation of persons suspected of having TB

- Uninterrupted supply of quality-assured drugs to treat TB

- Standardised treatment and care for all TB cases, including Directly Observed Treatment Short-course (DOTS)

- Setting up of a recording and reporting system through which the progress of patients and the overall performance of the TB control programme can be assessed. Box 13.1 outlines the records and forms that will be used to monitor the progress of your patients and how effectively TB is being controlled in your area.

Box 13.1 Record keeping and the TB patient

To help TB patients, you will need to know about different forms that need to be completed. For example, a TB lab register is used to record information on all patients investigated for TB; a sputum request form needs to be sent with the sputum samples that are sent for investigation. A TB unit register has to be completed for all patients where TB is detected, where the details of their treatment are recorded; there is also a TB referral/transfer form. Find out from where you work what these different forms looks like. Keeping them up-to-date is essential for checking the progress of patients and seeing how effective the control of TB in your area is proving.

Let us focus now on those components of the DOTS strategy that are carried out at the health facility and community levels. As you’ve just read, one of the most important components of the global strategy is the Directly Observed Treatment, Short-course, which means that a health worker or a treatment supporter (such an individual could be a family member, a religious or community leader) must support and watch the patient taking each dose of his/her treatment. DOTS is important to:

- Ensure that patients take the correct treatment regularly

- Detect when a patient misses a dose, find out why, and solve the problem

- Monitor and solve any problem that the patient may experience during treatment.

13.3.1 The Global STOP TB Strategy

The Global STOP TB Strategy was launched by WHO in 2006 to improve the achievements of the DOTS strategy (Figure 13.1). It comprises the following elements:

- Improve and scale-up DOTS so as to reach all patients, especially the poor.

- Address the problems of TB/HIV, drug resistant TB and other challenges.

- Contribute to health system strengthening by collaborating with other health programmes and general services, for example, in mobilising the necessary resources to make the health system work.

- Involve all public and private care-providers to increase case finding and ensure adherence to the International Standards for TB Care.

- Engage people with TB and affected communities to demand, and contribute to, effective care. This will involve scaling-up of TB control at community level by creating community awareness and mobilising local authorities and community members for action.

- Enable and promote research for the development of new drugs, diagnostic tools and vaccines.

The things that you can do in line with the Global STOP TB Strategy to reduce the problem of TB in your community, include educating the community members about TB, identifying community members with TB symptoms, making sure people know their HIV status, encouraging community members, active and ex-TB patients to participate in TB control activities, and finally persuading private health practitioners, including traditional healers to participate in TB control activities.

13.4 How is TB transmitted?

When an adult with infectious TB coughs, sneezes, sings or talks, the TB bacteria may be expelled into the air in the form of small particles called droplet nuclei, which cannot be seen except through a microscope. Transmission occurs when a person in close contact inhales (breathes in) the droplet nuclei.

Figure 13.2 shows an infectious TB patient expelling a large amount of droplet nuclei after coughing, and those nuclei being inhaled by a nearby person. If an infectious adult spits indiscriminately, the sputum containing bacteria dries and wind can carry the droplet nuclei into the air, so anyone can inhale them.

In addition, consumption of raw milk containing Mycobacterium bovi (TB bacteria found in domestic animals such as cows, goats and lambs) may also cause TB in humans, though nowadays it is much less frequent because of boiling milk or pasteurisation (the processing of removing germs from milk).

The contact person does not usually develop active TB immediately. In some cases, the person’s immunity is able to remove the bacteria and he/she does not develop TB infection. In other cases, the person develops an immune response that controls the bacteria by ‘walling it off’ inside the body. This causes the bacteria to become inactive. The person does not develop active TB or become ill at the time, but is said to have latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). Up to one-third of the world’s population is thought to be infected with latent TB.

A person with latent TB infection is well and cannot spread infection to others, whereas a person with active TB is sick and can transmit the disease.

If the immunity of a person with LTBI is weakened, the body is no longer able to contain the TB bacteria, which then grow rapidly and the person becomes sick with symptoms and signs of TB. The person is then said to have active TB. This process of progression from LTBI to active TB is called reactivation. The greatest risk for developing active TB is within the first two years following the initial infection.

13.4.1 Who is at risk from tuberculosis?

In a country like Ethiopia, with a very high number of TB cases, certain factors increase a person’s risk of developing active TB, either on first exposure or when a latent TB infection overcomes the body’s immunity to become active. These risk factors include:

- Poverty, causing poor living conditions and diet

- Prolonged close contact with someone with active TB

- Extreme age (the very young or old age groups), when the effectiveness of the immunity is lowered

- Malnutrition, which prevents the immune system from working properly

- Inaccessible health care, making it harder to diagnose and treat TB

- Living or working in a place or facilities such as a prison or a refugee camp, where there is overcrowding, poor ventilation, or unsanitary conditions

- Healthcare workers such as yourself, with increased chances of exposure to TB

- Lowered immunity factors, like HIV/AIDS or diabetes, drug treatments for cancer, and certain arthritis medications, will decrease the ability of the body’s defence mechanisms to keep the TB in check; this increases the chances of active TB developing.

13.4.2 Natural history of tuberculosis

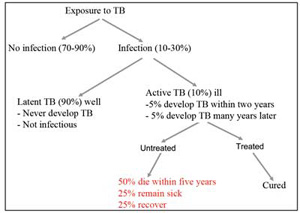

Look at Figure 13.3 which illustrates the different outcomes of a person exposed to TB infection. You can see that exposure to TB does not lead to infection of the contact in 70–90% of cases. For those 10–30% of individuals that do become infected with M. tuberculosis, in about 90% of them, the body’s immunity either kills the bacteria, or perhaps more often, keeps them suppressed (inactive), causing LTBI. (In HIV infected persons, TB infection progresses to disease more rapidly due to the weakening of their immunity.) In healthy individuals, only about 10% of infected persons develop active disease and become ill.

Without treatment, 50% of patients with pulmonary TB will die within five years, but most deaths are within two years; 25% will remain sick with chronic, infectious TB which can be spread to the community. Another 25% will spontaneously recover and be healthy, due to their strong immune defences, but they could become sick again at any time if the TB bacteria are latent.

13.4.3 What is the difference between TB infection and TB disease?

As you’ve just learnt, in a TB infection, an individual has no signs and symptoms of TB disease, whereas in pulmonary TB disease, signs and symptoms are evident. There are other differences between TB infections and pulmonary TB disease and these are summarised in Table 13.1.

| Descriptions | TB infection | TB disease (in the lungs) |

|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis in the body | Yes | Yes |

| Symptoms | No | Yes |

| Chest X-ray | Normal | Abnormal |

| Sputum smears | Negative | Usually positive |

| Culture* | Negative | Positive |

| Infectious to others? | No | Yes |

| A case of TB | No | Yes |

*TB bacteria isolated from the patient are grown in a culture medium in the laboratory, so they can be identified.

13.5 Case finding

Now it’s important you learn about how to identify a person with suspected TB and confirm a TB case in the community and at a health facility.

Detection of the most infectious cases of tuberculosis (sputum smear-positive pulmonary cases) is a critical step in the control of TB in the community where you are working. The process of determining a TB case is known as case finding. The objective of case finding is to identify the source of infection in the community, that is, individuals who are discharging large numbers of TB bacteria, so that they can receive prompt treatment, which in turn will cut the chain of transmission (stop the spread) and therefore lower the prevalence and mortality of TB.

The identification of people with suspected TB (or TB suspects) is the first step in case finding. The second step involves the laboratory investigation of the TB suspect’s sputum samples to confirm those who have active TB. This process is called TB screening. When selecting people for TB screening you should always be aware that certain individuals are at high risk of becoming infected and developing tuberculosis, in particular, contacts of those who are in prison, drug abusers, diabetic patients and People Living with HIV (PLHIV). You should educate the general public about the need for these high risk groups to be screened for TB regularly to reduce the burden of TB in the community. It is your responsibility to identify people in such groups at all times and to regularly refer them for sputum examination. It is also important to ask all household contacts of smear-positive TB patients whether they have been coughing and for how long they have been doing so. All children under the age of five years, anyone who is HIV-positive and any TB suspects among them in the family, or in prison should also be screened for TB.

13.5.1 How to identify a person with suspected TB

First, remember that you need to inform the general public about the signs and symptoms of TB and to tell them about where TB screening can be done.

How to suspect pulmonary TB

You can identify a TB suspect with pulmonary TB by asking two simple questions:

Remember that any person with a persistent cough of two or more weeks is a TB suspect and should be screened for TB.

- Do you have a persistent cough?

- How long have you had the cough?

You may also come in contact with persons who have extra-pulmonary TB, in which case you can use Table 13.2 as a guide on how to proceed. What is important for you to appreciate is that while a patient with EPTB is likely to have general symptoms such as weight loss, fever, night sweats, their specific symptoms will depend on which organ has been affected by the TB bacteria.

![]() Any person suspected of extra pulmonary TB should be referred to a medical doctor or clinician for diagnosis. If the patient is also coughing, sputum must be examined.

Any person suspected of extra pulmonary TB should be referred to a medical doctor or clinician for diagnosis. If the patient is also coughing, sputum must be examined.

| Organ affected | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Vertebral spine | Back pain, swelling on spine |

| Bone | Long-lasting bone infection |

| Joints | Painful joint swelling, usually affecting one joint |

| Kidney and urinary tract | Painful urination, blood in urine, frequent urination, lower back pain |

| Upper respiratory tract (larynx) | Hoarseness of voice, pain on swallowing |

| Pleural membrane of lungs | Chest pain, difficulty in breathing, fever |

| Meninges of the brain (meningitis) | Headache, fever, neck stiffness, vomiting, irritability, convulsions |

| Lymph node | Swelling of the node, draining pus. Long-lasting ulcer despite antibiotic treatment, draining pus |

How to suspect TB in children

What about diagnosis of TB in children? This is often quite difficult because sputum is not so easy to obtain. What is more, the symptoms are not as clear cut as in adults. They include:

- Low grade fever not responding to malaria treatment

- Night sweats

- Persistent cough for three weeks or more

- Loss of weight, loss of appetite

- Failure to thrive

- Lymph node swellings

Any child suspected of having TB should be referred to a Medical Officer/Clinician for diagnosis. The tuberculin test is a skin test to see if there is a reaction to extracts of TB bacteria.

Any child suspected of having TB should be referred to a Medical Officer/Clinician for diagnosis. The tuberculin test is a skin test to see if there is a reaction to extracts of TB bacteria. - Joint or bone swellings

- Deformity of the spine

- Listlessness

- Neck stiffness, headache, vomiting (TB meningitis).

Diagnosis in children rests largely on the results of clinical history, family contact history, X-ray examination and tuberculin test. A medical officer experienced in TB should make the decision whether to treat or not to treat.

13.5.2 Case finding through confirmation of a TB suspect by sputum examination

The purpose of sputum examination is to determine whether TB bacteria are present. You will need to collect three sputum samples (also called specimens) from each person with suspected TB for this purpose, as follows:

- First, explain to the TB suspect the reason for sputum examination and ask for his/her cooperation

- Then explain that examining sputum under a microscope is the best way to determine the presence of TB bacteria in the lungs

- Collect three sputum specimens from the TB suspect and write his or her name on the specimen containers (a small plastic bottle with a lid to prevent the spilling of the specimen while being transported to the laboratory).

How to collect sputum samples

You need three sputum containers on which the name of the suspect is to be written. Do not write the person’s name on the lid as this can cause confusion in the laboratory. Before you begin, explain to the person what collecting a specimen involves, and where possible guide him/her through the process. Begin by giving the person the container, then:

- Ask the person to open the lid and, holding the container like a glass of water, to take a deep breath and then cough out sputum (not saliva) into the container, without allowing sputum to spill on the edge or side of the container.

- Ask the person to put the lid on the container tightly.

- This first sample is collected ‘on the spot’. Keep the specimen in a safe place away from children, heat or sunlight. Heat or sunlight can kill the TB bacteria in the specimens (Figure 13.4).

- Give the person another labelled container to take home and collect a specimen immediately after waking up the next morning.

- Explain to the person that before collecting this second specimen, he or she should rinse their mouth with water so that food or any other particles do not contaminate the specimen. This second specimen is the ‘early morning specimen’. It is important to tell TB suspects to bring this second specimen with them when they come back to you the following day.

- When the person comes back with their ‘early morning’ specimen the following day, take the third specimen ‘on the spot’.

Box 13.2 summarises the key action points involved in collecting sputum for TB case finding.

Box 13.2 Important points to remember about sputum collection

- Use three containers labelled with the person’s name; do not write the name on the lids.

- Collect specimens in an open area or a well ventilated room

- Check that the lid is tightly closed after the specimen is collected

- Wash your hands with soap and water after handling the container

- Ensure that three specimens are collected and kept safely before sending them to the laboratory

- Send the specimens with a request form to the nearest laboratory for examination.

- Tell the TB suspect when to come back for the laboratory result

- If the sputum is positive and the person does not come back to hear the result, then trace him or her as soon as possible, and explain the outcome and refer them for treatment. Treatment needs to be started immediately to prevent the spread of TB.

Summary of Study Session 13

- Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as TB bacteria.

- Pulmonary TB affecting the lungs is the commonest type of TB; extra-pulmonary TB arises when TB affects other organs of the body.

- TB is a major health problem in Ethiopia and around the world. The Global STOP TB strategy, including DOTS (directly observed treatment, short-course) is designed to reduce the level of TB infections and transmission.

- Transmission of TB occurs mainly by inhalation of infectious droplets produced when an untreated person with TB coughs, sneezes, sings or talks.

- Identification of the most infectious cases of tuberculosis (sputum smear-positive pulmonary TB cases) by screening sputum smears is crucial to TB control.

- Three sputum specimens are sent in labelled containers to the laboratory for sputum examination. Tell the TB suspect when to come back for the result.

- If a person who is smear-positive fails to come back for the report, locate and inform him or her about their TB status as soon as possible. Treatment needs to be started immediately to prevent the spread of TB.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 13

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 13.1 (tests Learning Outcome 13.1)

In lay person’s language, how would you describe TB and its symptoms to a person who comes to your Health Post? Explain why it is important to follow the treatment exactly.

Answer

In language a lay person could understand, you would say first that TB is an infectious disease caused by TB bacteria (germs). It is a disease that normally affects the lungs, though it can infect other parts of the body too. The symptoms of TB are a persistent cough, weight loss, chest pain, tiredness, difficulty breathing, sweating, fever and sometimes the spitting up of blood. When someone with TB coughs or sneezes they breathe out droplets that contain the bacteria. If these droplets are breathed in by a healthy person, they could also become infected with TB.

Most people infected with TB bacteria do not go on to develop TB. Instead the bacteria remain ‘asleep’ in their bodies, and in some cases they may even clear the bacteria completely. However, those who do develop an active infection will die in a few years if not treated. The treatment of TB takes many months and it is important that those undergoing treatment follow the treatment exactly. This ensures a good outcome and also prevents the development of drug-resistant strains of TB which are more difficult to cure.

Tell the person that if he or she suspects they or someone in their community may be infected, then please seek medical treatment at the nearest health facility. Children and those with other conditions, such as HIV, are very susceptible to TB infection.

SAQ 13.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.1 and 13.2)

What are the global targets for TB case finding and treatment?

Answer

The global targets for TB case finding and treatment are to detect at least 70% of the smear-positive cases and cure at least 85% of the detected cases.

SAQ 13.3 (tests Learning Outcome 13.2)

If the population of a woreda in Tigray is 200,000 people, what is the estimated number of new smear-positive TB cases? (Remember in Ethiopia as a whole, the estimated number of new smear-positive TB cases is 163/100,000 annually.)

Answer

326 new smear-positive TB cases are expected in 200,000 people. (Remember that in Ethiopia as a whole, in 100,000 people a total of 163 new smear-positive cases are expected every year. Therefore, in 200,000 people you would expect 2 × 163 = 326 cases).

SAQ 13.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.1 and 13.3)

What are the components of the Global STOP TB Strategy?

Answer

The main features of the Global STOP-TB Strategy are practising and scaling-up DOTS, addressing MDR-TB and TB/HIV co-infections, supporting the strengthening of the health system, and engagement with stakeholders such as public and private care-providers and the affected communities to raise detection, treatment and adherence to high standards. In addition, the strategy enables and promotes research into new drugs, diagnostic tools and vaccines.

SAQ 13.5 (tests Learning Outcome 13.4)

How is TB spread?

Answer

When an infectious adult coughs, sneezes, sings or talks, the tubercle bacteria may be expelled into the air in the form of droplet nuclei. Transmission of the TB bacteria occurs when a person in close contact inhales (breathes in) the droplet nuclei.

SAQ 13.6 (tests Learning Outcome 13.5)

How does a health worker identify TB suspects from among all the persons in the community, or those visiting a health facility?

Answer

Case finding strategies in these circumstances are intensified TB-screening in high-risk groups and screening of people who have been in close contact with them.

SAQ 13.7 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.1 and 13.5)

A person with smear-positive pulmonary TB lives with family members in your community. Whom among the family members are you going to screen for TB by sending sputum specimens to the laboratory?

Answer

The following people should be screened for TB in the family of someone with active TB:

- Children less than five years old

- Anyone who is HIV-positive

- All family members (children older than five years and adult) who have any symptoms of TB.