Exploring languages and cultures

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 16 February 2026, 10:15 AM

Exploring languages and cultures

Introduction

Learning a language requires an understanding the cultures of its speakers. This free course, Exploring languages and cultures, explores the multiple relationships between languages and cultures. You will learn about the benefits and challenges of meeting people from different cultures, what it means to be plurilingual and pluricultural, and the ways in which language and human communities shape each other. You also will look at the role of intercultural competence at the workplace, reflect on the use of English as lingua franca in international contexts, and get a flavour of the skills involved in language-related professions such as translation and interpreting.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course L161 Exploring languages and cultures.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course you should be able to:

explain what intercultural encounters are and how people can learn from them

discuss how the use of English as a lingua franca is perceived by native and non-native English speakers

illustrate how different groups of people (e.g. professions) develop their own languages and cultures

describe the role of intercultural competence in a business environment

outline the skills and contexts involved in translating and interpreting professions.

1 Intercultural encounters

An intercultural encounter takes place when you become aware that you are interacting with a member of a different community whose ways of thinking are quite distinct from your own. These experiences often occur when you go abroad, but they can take place in any society that has many different cultural groups, such as the UK, for example. During an intercultural encounter, you become aware that you and the other person are operating according to different sets of beliefs and values. This may mean that you are acting in ways that are unfamiliar to each other, which can provoke a sense of unease in one or both participants. But such encounters can offer significant learning opportunities, provided that you use them to think about your own expectations, and to explore the cultural assumptions that appear to be shaping your behaviour and that of the other person (your interlocutor). Reflection of this kind is one of the main ways in which you can acquire what is known as intercultural competence.

In this section you will look at two different encounters and will begin to think about examples drawn from your own experience.

1.1 An encounter in a shop

In the BBC Bakeation series, two celebrity bikers with a passion for travel and cooking, known as the Hairy Bikers, visited several European countries to discover their baking traditions. Hairy Biker Dave studied French at school and worked in Luxembourg for a few months. In the following video he puts his French to the test to buy saucisson lyonnais (a type of sausage).

Activity 1

Watch the video and write your answers to the questions in the boxes below.

Transcript: Dave tries out his French

1 How does the shopkeeper respond to Dave’s efforts to address her in French?

Answer

The shopkeeper consistently replies to Dave in English.

2 Why do you think the shopkeeper answers the way she does, despite the fact that Dave addresses her in French?

Answer

We can only speculate why people like the shopkeeper respond in their own language, but such behaviour is very common. If you are making great efforts to address people in their own language, it can be frustrating to be denied the opportunity of engaging in a two-way conversation in the target language. Here the shopkeeper may be answering in English for a number of reasons:

- She may be trying to be helpful.

- She may be keen to practise her English.

- She may want to appear professional and good at English, able to address customers in their own language.

- She may prefer communication in English rather than in broken French. This does not necessarily imply a negative judgement on Dave’s linguistic ability. She may simply feel that the conversation will be smoother and easier if it is conducted in English.

3 Have you ever found yourself in a similar situation? If so, how did you feel?

Answer

If you have experienced such a situation you may have felt frustrated that the person didn’t respond in the same language, or annoyed about the implication that your use of the foreign language wasn’t very good. Conversely, perhaps you felt thankful that your use of language had obviously been understood.

1.2 A German dinner party

The next intercultural encounter features a British journalist, working in Germany, and his perceptions of a German dinner party.

Dinner parties are a very common type of social occasion and may generate intercultural encounters. The text you are about to read is a personal account of such an encounter. You will probably notice that the author uses two types of argument in his discussion of the experience. The first is argument by analogy, which involves comparing two things in order to highlight a perceived similarity. By its nature, an analogy offers a simplified view of an idea or process – an illustration, rather than a detailed analysis. The second is generalisation, which involves basing general propositions on the observation of particular details. Both are flawed forms of argumentation: analogies invariably break down, while generalisations often prove unsustainable in the face of further evidence. Neither is to be trusted when trying to make sense of other cultures.

Activity 2

Read the article and identify three generalisations and one argument by analogy made by the author.

Reading 1 Frugality rules at German dinner parties

This photograph shows a large saucepan of boiled potatoes.

There has been much talk in Germany about southern European nations being over-reliant on the country’s generosity but when it comes to entertaining, the Germans display quite an appetite for frugality.

When I first came to live in Berlin, I was invited to a dinner party, a media dinner party. A German director and his wife invited me over and I looked forward to it with great anticipation.

Usually dinner parties are not my cup of tea, as it were, but this would be a chance to see how Germans did these things. A correspondent from The Economist had also been invited.

And it was good, very enjoyable – though not nearly as grand a meal as I had anticipated.

The table was laid in the couple’s flat. We chatted a little, anticipation mounting.

And then his wife proudly produced the food – boiled potatoes, boiled green vegetables and ham, boiled ham.

Now I like boiled potatoes, boiled ham, boiled vegetables even.

But it is not what you would have expected in a similar British dinner.

That would have been a feast, produced to the dictates of Delia, Jamie or Heston and probably involving porcini and crème fraiche, the words the English upper-crust use for mushrooms and sour cream.

The point I am making is that the German idea of luxury is different from the British idea.

Germans really are frugal. They like boiled potatoes – and good for them, say I.

You might argue that this was Berlin and Berlin was, of course, partly in East Germany. So Berlin frugality has a different background. And it is true that East Berliners were mocked by ‘Wessies’ when the wall came down because they knew nothing about fancy food.

Just after the two halves of the city were reunited, a West German magazine [Titanic] had a cover story with a picture of an East German housewife. You could tell where she came from because of her awful East German perm. She is holding a cucumber and the caption says: ‘My first banana’.

The point is that bananas were such a luxury that East Germans could not even recognise one.

But the hosts at my dinner party were not ‘Ossies’ but ‘Wessies’, completely au fait with bananas and even, perhaps, porcini.

No, this was just German frugality. You come across it in lots of ways.

I go to a supermarket under a railway arch and it resembles a warehouse, goods stacked to the red-bricked roof with no sense of style or flashy salesmanship.

It is price that matters – even for fancy wines.

This is not a supermarket for poor people. There is wine there at 60 euros (£48/$76) a bottle. But you can bet your bottom euro that it will be cheaper than elsewhere. Even the rich watch the pennies.

Or think of Media Markt, the electronics retailer, which still refuses to take credit cards or even debit cards.

When I presented a card at the check-out, the assistant looked at me like I had offered to pay with a chicken or the use of my body for half an hour. Credit: nein danke.

So as you follow the debate over the euro, and over German resistance to extra spending in Greece, or extra spending in Brussels, bear this frugality in mind. It is seared into the German soul.

[…]

Much is made of the effects of the inflation of 1923, but to my mind that is overblown – a cliché almost.

Far more important are the effects of the World War II, which are less talked about, partly because German suffering became unmentionable because of guilt.

But it was a personal catastrophe for millions of people. Half the homes in Germany were uninhabitable, either destroyed or damaged.

So these are people who experienced great privation, and within living memory. American cigarettes became a currency as people scrabbled for food.

In this city of Berlin, for example, women – Trümmerfrauen (rubble women) – scrabbled through the streets, scavenging in the years after the war. That kind of experience has to inform your attitude to food and material goods.

On top of that, Germans do not actually earn very much compared to those in other European countries – less than in France and Spain and about two-thirds what a comparable British worker has.

And the German wage has barely risen over the past decade. They are frugal because they hold back on pay.

Accordingly, Germans hold their wallets tight to themselves.

Frugal at the dinner table. Frugal too, in the finance ministry.

Note: Delia (Smith) is a TV cook and cookery writer in the UK, and Jamie (Oliver) and Heston (Blumenthal) are ‘celebrity chefs’. Titanic was a satirical magazine, so the cover photo described was obviously a joke. Far from not being able to recognise bananas, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, East Germans used to buy large quantities of bananas in the West to take home.

Answer

Argument by analogy: ‘Frugal at the dinner table. Frugal too, in the finance ministry.’

Generalisations include:

- Germans are frugal.

- British dinner parties are feasts, cooked to the dictates of celebrity chefs.

- The German idea of luxury is different from the British one.

- Germans like boiled potatoes.

- Germans hold on tightly to their wallets.

Activity 3

Read the article again, and answer the following questions.

1 How many dinner parties does the author of this article report on?

Answer

The article seems to be based on only one dinner party.

2 What trait does the author attribute to Germans in general, on the basis of his experience?

Answer

The author generalises that Germans are frugal.

3 What cultural difference between Britain and Germany does he write about, on the basis of this dinner party?

Answer

The author asserts that ‘the German idea of luxury is different from the British idea’.

4 Which historical event does the author suggest contributed to the perceived German frugality?

Answer

He attributes this difference to the widespread poverty and hardship that followed the Second World War.

5 What three examples does the author use to support his conclusions about German frugality?

Answer

The author uses four examples:

- the fact that his local supermarket resembles a warehouse, and puts low prices before ‘flashy’ sales techniques

- the insistence of the Media Markt electronics chain on payment in cash

- the fact that German wages are low.

Activity 4

Think about the following questions, which are designed to help you evaluate the arguments presented in this article.

1 The author concludes his article by drawing an analogy between German culinary preferences and economic practices: ‘Frugal at the dinner table. Frugal too, in the finance ministry’. How robust, in your view, is this analogy?

Discussion

As you saw in the introduction to this activity, analogies always break down. The analogy between German culinary preferences and economic practices does not seem strong. In a country as large and as varied as Germany, food preferences and specialities are often regional and frequently reflect traditions that have been established over centuries. Economic policy is more likely to be a complex and conscious response to the perceived needs of the present moment, which takes into account Germany’s wider responsibility as the leading economic power in the eurozone. The author is basing his observation on just one dinner party, which is a very small sample, and the menu choice could have been down to the hosts’ preferences as an individual couple.

2 Discuss the following statement on the basis of your own experience and supporting your comments with evidence:

‘a similar British dinner … would have been a feast, produced to the dictates of Delia, Jamie or Heston and probably involving porcini and crème fraiche …’

Discussion

The author’s statement refers to three TV personalities, Delia Smith, Jamie Oliver and Heston Blumenthal, each of whom has a distinctly different approach to culinary matters. It is doubtful whether the average British household has the expertise, or the equipment, to cook in Blumenthal’s highly technical way. His mention of porcini and crème fraiche, which are arguably ‘foreign’, fashionable ingredients, coupled with the TV cook name-dropping, implies that the author’s idea of a British dinner party seems much more trend-oriented than the German soirée he attended, and he explicitly contrasts his idea of a British dinner ‘feast’ with the German frugal fare. It could be argued that he is generalising though with both ‘national’ examples, and that the author’s experience of dining out seems restricted to a relatively small segment of the population, both socially and regionally.

1.3 Reflecting on cultural differences

In intercultural encounters we often come across behaviours that would seem odd in our own culture, but there is often a valid reason for such behaviours. It is therefore always worth taking a moment to consider alternative explanations and to remember that, even with an open mind, our own interpretations can be mistaken.

Activity 5

Think of three possible explanations for the frugality of the meal offered to the author by his German hosts.

Discussion

Here are some possible explanations. You may have thought of others.

- The person preparing the meal had limited culinary skills.

- Dietary restrictions meant that the host couple were unable to eat rich or elaborate food.

- The hosts had heard stereotypes about British cooking and thought that their guests would prefer simple fare.

- The hosts had had a busy day and did not have time to shop or cook.

- The hosts did not think the occasion was particularly special.

- His hosts wanted him to try a traditional German meal.

Activity 6

The best way to avoid unhelpful cultural generalisations is to find ways of checking whether your assumptions are correct. Think of three ways in which the author of ‘Frugality rules at German dinner parties’ might have tried to verify his assumptions about ‘German frugality’ before writing this article, without offending his hosts.

Discussion

To check his proposed explanations, the author could have:

- tried to attend other dinner parties

- asked his fellow dinner guest for his or her opinion of the meal they had eaten

- made inquiries at his local supermarket, about the reasons for its layout

- undertaken an experiment: e.g. given frugal or sumptuous dinners to German guests and canvassed their reactions

- surveyed a broad range of German acquaintances about their attitudes to food and finances, rather than generalising on such limited evidence.

1.4 Interview with Professor Byram

You will now listen to an interview with Professor Mike Byram, who has been very influential in the area of intercultural communicative competence in Europe. Working in collaboration with other scholars, as part of a project funded by the Council of Europe, he developed the concept of intercultural encounters.

A head and shoulders photograph of Mike Byram, smiling and wearing glasses, a trimmed grey beard and a suit and tie.

Activity 7

Listen to ‘Interview with Mike Byram’. As you listen, think about the following question and write your answer in the box:

How does Mike Byram define an intercultural encounter?

Transcript: Interview with Mike Byram

Answer

Byram defines an intercultural encounter as a situation in which someone interacts with a person from another social group and where group identity plays a prominent role. This means that different behavioural norms and different sets of values and beliefs are apparent and may be the source of some unease.

Activity 8

a.

Someone from the north-east of England has a meeting with someone from the south.

b.

Two people of different professions interact with each other.

c.

An Argentinian footballer is sent off by an English referee.

d.

A Protestant teacher educator visits trainees in a Catholic school.

e.

An exchange student from China visits the nightclubs of Newcastle upon Tyne.

f.

A British academic visits the USA.

g.

A singer from the USA is interviewed by a reporter from the north of England.

h.

A Romanian visitor spends the night as a guest of the Queen at Buckingham Palace.

The correct answers are a, b, d and f.

Activity 9

In the interview Mike Byram gives four examples of intercultural encounters, each of them illustrating a particular type of difference. The first one he mentions is a British academic visiting the USA. In this case, his example illustrates national differences. What other kinds of differences do the remaining examples illustrate? Use one word to describe each.

1 Someone from the north-east of England has a meeting with someone from the south.

Answer

Regional

2 Two people of different professions interact with each other.

Answer

Professional

3 A Protestant teacher educator visits trainees in a Catholic school.

Answer

Religious

1.5 What about you?

As you have seen, a culture may seem unfamiliar to you for a variety of reasons. Nation and language may be the most visible sources of cultural differences, but there are many more such as religion, gender, profession, or age. Some of these are very obvious, whereas others are more subtle but no less meaningful.

Activity 10

Think about two specific intercultural encounters involving yourself and a person from a context that is different from your own. (They could, for example, be from a different country or different region or differ in terms of occupation, age, sexual orientation or religion.) The encounters should have been significant or unusual, for some reason. One of them should have been unsuccessful or challenging, and the other one successful.

Describe each of them in 100–125 words, explaining what made it significant or unusual and why you think it was successful or unsuccessful. Record your answers in the box below.

Answer

Here are two examples drawn from the experiences of one of the authors of this course as an amateur musician.

An unsuccessful encounter

Some years ago I joined a weekly folk music group in north-east England. Being Spanish, I was hoping to make some English friends and learn some English folk music. Unfortunately, the director insisted on talking to me as though I could barely understand English, perhaps because I had to keep translating guitar chord names from ‘C–D–E’ to ‘do–re–mi’. Despite my best efforts to demonstrate that I was able to give perfectly articulate responses, he would simply fail to notice that I could actually speak English. To make matters worse, other group members did pretty much the same and I never understood why. After a couple of months I just left and found myself a local singing group, where I was finally allowed to hold a normal conversation.

A successful encounter

At the end of a dinner party at home, a few of us started to play the Paraguayan harp. One of my colleagues, who was Korean, fell in love with the instrument and asked me to teach her how to play it. We met every week until I taught her all I knew, which was not much. Eventually she decided that Latin-American music was too alien to her and she switched to the clàrsach (Celtic harp). By then we had become very close friends, so much so that I asked her to be my daughter’s godmother. We visit each other regularly and often end up comparing our experiences as foreign residents in the UK. She is now a proficient harpist; I am not.

The two examples provided above show that not all intercultural encounters necessarily revolve around nationality (British meets Spanish; Spanish meets Korean) as the main source of cultural differences, and show that other aspects of culture are important too.

In the first example, differences in musical traditions and practices were probably just as important as, if not more important than, national or linguistic differences. Once the Spanish musician moved from an instrumental folk group to a singing group in the same town, she no longer experienced communication problems despite the fact that in both cases all the other group members were British. Perhaps something about her behaviour did not meet the unwritten rules for interacting with others in instrumental folk groups, whereas the same behaviour was regarded as normal in a singing group. Another explanation could be that she was more assertive or proficient as a singer than as a folk guitarist, and this competence made the other singers perceive her as more linguistically competent too.

In the second example the encounter may have been successful because the two participants shared an interest in harp music and the relationship developed around one person helping the other.

2 Using a lingua franca

People have been on the move throughout history. In the process, they have encountered other people from different cultures who speak different languages. In order to work with them, to trade with them and, in some cases, to govern them, a language was needed that both sides could communicate in. From repeated encounters between peoples, new forms of language emerged. This course looks at the languages which developed and grew at the meeting points between cultures and peoples.

In this section you look at the history and meanings of the term lingua franca and discover how the use of English as a lingua franca is perceived by native and non-native English speakers working together on an international project.

2.1 The term ‘lingua franca’

The first use of the term ‘lingua franca’ was recorded in 1553. The term franca (literally ‘Frankish’) was at one time used to referred to western Europeans, and lingua franca (meaning ‘language of the Franks or western Europeans’) was an Italian expression for the language that came to be used for communication purposes between traders in the Mediterranean area. Since then, the meaning of the term has evolved.

Activity 11

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) gives the following meanings for the term ‘lingua franca’:

- A pidgin language drawing its lexicon mainly from the southern Romance languages and formerly used as a trading language, first in the eastern Mediterranean and later throughout much of northern Africa and the Middle East. Frequently with capital initials. Now historical.

- Any language that is used by speakers of different languages as a common medium of communication; a common language.

- In early use sometimes specifically denoting a mixed language that fulfils this role.

- In figurative contexts: a generally understood or commonly used standard, system, or means of non-verbal communication.

The OED also gives a list of examples for each of these uses. Indicate which of the meanings 1 to 4 above each of the examples below illustrates:

a.

1

b.

2

c.

3

d.

4

The correct answer is b.

a.

1

b.

2

c.

3

d.

4

The correct answer is c.

a.

1

b.

2

c.

3

d.

4

The correct answer is d.

a.

1

b.

2

c.

3

d.

4

The correct answer is a.

Activity 12

Now look at these further examples, where the term is used in the plural form. Why do you think the three plurals are different?

- These [native American languages] the missionaries have converted into Lingua Francas.

(1857, Encycl. Brit. XIII. 195/1, cited in Oxford University Press, 2013a)

- A very complex infrastructure of scores of vernacular languages as well as a number of regional lingue franche.

(1971, J. Spencer Eng. Lang. W. Afr. 31, cited in Oxford University Press, 2013a)

- Tribalism, linguae francae and the emerging states

(Samarin, 1961).

Discussion

In these cases different writers have assigned different plural forms to the term ‘lingua franca’ depending on their understanding of which language the term ‘belongs to’ – although given the mixed origins of the original Lingua Franca this is not an easy thing to decide! In the first example, ‘Lingua Francas’, the author is treating the term as English, with a plural ‘-s’ added to the second element. In the second example, ‘lingue franche’, the author is treating the term as Italian, changing the endings of both elements in accordance with Italian grammatical and spelling rules. In the third example the author is treating the term as Latin, this time changing the endings of both elements in accordance with Latin grammatical and spelling rules.

2.2 English as a lingua franca

We now turn to the most successful lingua franca the world has ever seen, certainly in terms of the number of speakers – English.

In the next activity, you will listen to various people who have been working together on a project. Only one of them is a native speaker of English, yet they have used English as their lingua franca throughout the project. In this sense, they are like thousands of project teams throughout the world who, at any one moment, are communicating in English in fields such as science and business.

Activity 13

Listen to Teija, Nadia and Jim talk about their experiences of working together in English. Jim is the only native speaker of the language in the group.

As you listen, make notes about the advantages and disadvantages of using English as a lingua franca from the perspectives of the non-native and native speakers on their project. Type your notes into the appropriate spaces below.

Transcript: Magicc

1

Advantages of using English as a lingua franca on the project:

(a) from the non-native speaker perspective

(b) from the native speaker perspective

2

Disadvantages of using English as a lingua franca on the project:

(a) from the non-native speaker perspective

(b) from the native speaker perspective

Answer

Given that some sort of shared language needs to be used by the participants in this project, the central advantage of English as a lingua franca, from the non-native speaker perspective, is that it is the language of the domains they are discussing. There are, however, three disadvantages mentioned from a non-native viewpoint, disadvantages that could be applicable to any language in which a speaker does not have native-like fluency: it can be tiring, requiring high concentration levels when speaking and listening; there may be a sense of reduced personality in that it is difficult to do justice to one’s ideas or use humour in the same way in a second language; finally, it is time-consuming.

From the native speaker perspective, the principal advantage is that of working in one’s own first language. Nevertheless, there may also be disadvantages: as for the non-native speakers, it may be tiring, due to the high level of concentration required when listening to non-native speakers, and Jim also mentions his feeling of inadequacy and being overawed by others’ linguistic abilities.

The discussion seems to portray the use of English in a rather negative light. Although its practical advantages are acknowledged in passing, the psychological difficulties of operating in a lingua franca are emphasised, along with the physical strain of maintaining the concentration levels required for successful interaction. The next part of the discussion strikes a more upbeat tone.

Activity 14

As you listen to the next conversation, make notes on the liberating and constraining aspects of speaking English as a lingua franca. Then type your answer into the box below.

Transcript: Magicc Project

[interposing voices and laughter]

[laughter]

Answer

Jim talks of how English is no longer the property of British or American native speakers but is being exploited by a variety of different groups and nations. Teija follows this up by mentioning how being able to draw upon the resources of English while also having a first language which others do not understand is a form of liberation. Her words are reminiscent of a vision expressed by Robert Phillipson, a British linguist who sees English as an ‘additive’ resource which speakers can exploit for particular purposes without suffering a ‘subtractive’ effect on their own language (Phillipson, 2009).

However, the drawback of this notion of English as an additive resource is expressed by Nadia who resents the fact that she cannot communicate effectively in her native tongue about her scientific field of expertise. This is because English is the default language of science. If particular fields are predominantly discussed and written about in English, the danger of speakers of other languages experiencing what Phillipson describes as ‘dispossession’ seems to be very real. Jim’s anecdote about the Austrian woman confirms this danger. She suddenly had the sensation of being linguistically dispossessed because exposure to Dutch and English at different stages in her life left her feeling that she had mastery of none of her languages, not even her first language, German.

3 Languages, cultures and communities

Language reflects the groups we belong to. Traces of our class, age, gender, background, profession and pastimes can often be found in the language that we use. As a result, language plays a central role in the identities that we project to the world. In this section you will look at the functions and characteristics of slang and jargon used in different group cultures and subcultures. Every profession also has its own terminology, and you will explore the subtle boundaries between terminology and jargon. The academic world is another context where the appropriate use of language is paramount, and the final part of this section looks at some of the features of academic style.

3.1 Language communities

As well as exploring the relationship between language and the broad categories that people belong to, such as class and age, sociolinguists have in recent years tried to capture the complexity and dynamism of people’s social lives. This has involved investigating the smaller social units they move between, and how their language and behaviour shapes and is shaped by these units. These smaller units have been categorised in various ways. One such category is the ‘community of practice’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991). As the name suggests, such a group comes together around a mutual endeavour of some sort. So, a book club or a church choir can each be described as a community of practice. These smaller groupings can easily form, change and disappear.

Activity 15

Below is a list of leisure activities. In taking up these activities, people often join like-minded individuals and form their own small social communities (clubs). Look at the list and try to decide the gender, age and socioeconomic class of people who you would expect to do these activities, then do the same with two further activities you have come up with yourself. In the box below each activity give a short profile of the most likely type of participant. The first example has been completed for you.

As with any generalising activity, there is the danger of oversimplification. However, it should become clear that the broader social categories of age, gender and socioeconomic class have some influence on the kinds of pastimes people gravitate towards.

Playing squash

Singing in a choir

Ballet dancing

Being part of a book club

Playing football

Doing yoga

Boxing

Other activity 1

Other activity 2

Answer

There are no correct answers to this activity, as this is based on your own perceptions. Below are the responses of one British person living in the UK. Compare them and see where yours are similar or different.

| Activity type | Likely group age, gender, class |

|---|---|

| Playing squash | Young to middle-aged, both sexes but mostly male, middle class |

| Playing bingo | Middle-aged and older people, predominantly female and working class |

| Keeping an allotment | Was traditionally working class but more middle-class people are taking it up; used to be mostly male but that is changing |

| Singing in a choir | Depends on the type of choir: cathedral choirs are often middle class, of all ages, including boy choristers; male voice choirs are typically middle-aged men; gospel choirs are often made up of people of African-Caribbean descent |

| Ballet dancing | Young, female and usually middle class |

| Being part of a book club | Middle class, mostly female |

| Playing football | Was almost exclusively male and working class; now, more females are taking up the game |

| Playing bridge | Middle class and middle-aged; not sure about balance of sexes |

| Doing yoga | Middle class and predominantly female |

| Racing pigeons | Working class, male, generally of the older generation |

| Lawn bowling | Middle-aged and older people, both sexes, working class |

| Boxing | Traditionally, working class and male; however, it has been taken up by more females in recent years, as indicated by the introduction of women’s boxing competitions at the London 2012 Olympics. |

Doing this exercise should highlight how much the smaller communities of practice that people choose to join are, to some degree at least, influenced by their class, age and gender. The fact that some of the activities listed (such as lawn bowling, bridge and bingo) are not international in scope shows that the nation people belong to also influences or limits their choices.

Furthermore, the typical profiles of members might be different depending on the particular context. There are, for instance, various types of choir. A typical church choir may bring to mind white, middle-class and middle-aged singers. However, you only have to think of gospel or Welsh male-voice choirs to dispel the notion that all choir members fit this profile. Remember also that communities of practice are never static and as a result, the profile of a ‘typical’ member is always evolving. For instance, in a growing number of countries, football is no longer the all-male preserve that it once was.

Of course, people can ignore social conventions when deciding which clubs and groups to join. It simply takes more courage to do so. Think for example of the film Billy Elliot (2000), where a working-class boy challenges the norms and expectations of his community in order to become a ballet dancer.

Although there may not be many explicit rules, there are often particular norms of behaviour and, indeed, ways of talking which people need to learn to become part of a community of practice.

Activity 16

Here is a letter written to an archery magazine. As you read it, think about the following questions and make notes in the box below the letter.

- How much of it can you understand?

- Are there words used which you either don’t know or which have different meanings to their everyday ones?

- Why do you think these specialised meanings exist?

Reading 2 ‘Thin’ not always best

I am writing in response to a letter in the spring issue headed Time for change?

I just wanted to say that from personal experience that thinner arrows in fact do more damage to bosses than fatter arrows. During the indoor season I shot both fat arrows (Easton Fatboys) and thin arrows (Easton ACCs) both with a 51 lbs recurve and found that the thinner arrows went through the boss quicker than the fat arrows. Both sets were shot at identical new straw bosses and I found that after shooting two to three Portsmouth rounds the thin arrows were going through the boss, where as it took six to seven Portsmouth rounds before the fat arrows went through.

I have also witnessed similar results under similar conditions by an archer shooting only 28 lbs with both fat and thin arrows. The main reason for this is due to the arrow speed as the fat arrows travel more slowly and will stop more quickly. So if there was to be a change to the line cutter rule to encourage the use of thinner arrows it would, in fact, increase the damage to those expensive bosses.

David Cousins, Lizard Peninsula Bowmen

Discussion

Even if you do not know the language of archery, you might well be able to grasp the general issue which the writer is discussing: the relative merits of using fatter or thinner arrows in terms of the damage they do to the ‘boss’. The meaning of ‘boss’ is not obvious for someone who knows nothing about archery, but the context suggests that it may be the target or a part of it. However, there are sections of the letter that are puzzling to non-archers. What does the ‘51 lbs recurve’ refer to? Does the mention of ‘28 lbs’ also refer to this recurve? What is ‘the line cutter rule’? What are ‘Portsmouth rounds’?

Obviously, some specialist language is needed in order to talk about the particular equipment that is used in archery and the rules of the sport. Archers need to be familiar with the terms of archery, much as a car mechanic has to be familiar with the different parts of an engine and what they are called. However, this practical explanation is only half the story. The use of these terms communicates to the readership of the archery magazine that the writer is part of their community, that he belongs.

3.2 Slang

'Slang’ and ‘jargon’ are terms often used interchangeably because they are both sociolects. In other words, they are both varieties of language used by a particular social group or class. However, while jargon (written or spoken) tends to be terminology associated with certain professions or social activities, slang is more commonly associated with the spoken language, and with social groups whose values and practices differ from, and sometimes antagonise, those of the majority or dominant group in their society. The values, beliefs and practices of such minority/non-dominant groups are sometimes referred to as ‘subcultures’.

In this section you will look at slang from a number of different languages in order to work out what they have in common, especially in terms of their role in relation to the corresponding mainstream cultures.

3.2.1 Cockney rhyming slang

A key social function of the language of a group is that it serves to include some and exclude others. In some cases this constitutes a form of language code which is consciously used so that outsiders do not understand. A famous example of this is Cockney rhyming slang from the East End of London. A Cockney is someone ‘born within the sound of Bow Bells’ – that is, within earshot of the bells of the church of St Mary-le-Bow, Cheapside – but the term ‘Cockney’ is often used more broadly to describe working-class Londoners and their speech.

Rhyming slang probably originated in the first half of the nineteenth century. It works by substituting the word that is meant (e.g. ‘look’) with a common phrase that rhymes with it (e.g. ‘butcher’s hook’). The rhyming word in the new phrase is then omitted (e.g. the word ‘hook’, so ‘look’ becomes ‘butcher’s’: ‘Have a butcher’s at this!’). So, to take another example, if you want to say ‘tie’ in rhyming slang it would be ‘Peckham’ (the full phrase would be ‘Peckham Rye’ – referring to another area of London – with the ‘Rye’ omitted.). It is worth noting here that this only makes sense if you know the geography of the local area.

This is a photo of a Pearly King and a Pearly Queen showing a man and woman whose jackets and hats are decorated with thousands of shiny mother-of-pearl buttons.

Activity 17

Below is some Cockney rhyming slang. See if you can guess the missing elements and type them into the spaces below. The first two have been done for you.

1. Hampstead (Heath) = teeth

2. apples (and pears) = stairs

3. trouble (____ ____) = wife

Answer

trouble (and strife) = wife

4. loaf (____ ____) = head

Answer

loaf (of bread) = head

5. rabbit (____ ____) = talk

Answer

rabbit (and pork) = talk

6. porky (____) = lie

Answer

porky (pie) = lie

7. plates (____ ____) = feet

Answer

plates (of meat) = feet

8. dog (____ ____) = phone

Answer

dog (and bone) = phone

Cockney rhyming slang has spread beyond its geographical origins. It is always evolving and often incorporates contemporary cultural allusions. To take just one example, a lower second-class university degree (2:2) can be referred to as a ‘Desmond’, after the famous South African cleric, Desmond Tutu. Speakers are free to make up their own and often do.

3.2.2 Polari, argot and Lunfardo

You will now listen to three audio clips in which members of the Open University’s Department of Languages talk about slang used in three different cultures: English Polari, Argentinian Lunfardo and French argot.

As you listen, it is worth bearing in mind that the origins of particular varieties of language are never easy to date with any precision, especially as they often evolve from the language environment around them.

Activity 18

Listen to the following audios and try to identify the main similarities and differences between these three sociolects. As you listen you may find it helpful to focus on the following aspects:

- how they originated: who spoke them and why

- how words and expressions are formed

- attitudes of mainstream society/culture towards their use

- present usage.

Transcript: Polari

Transcript: Lunfardo

Transcript: Argot

1 What similarities were you able to identify between Polari, Lunfardo and argot? Make a note of them in the box below.

Answer

- All three evolved, in part, as a secret code for speakers to use as a means of excluding the wider society from their communications. Inevitably, this exclusive function also generated an inclusive one, building a sense of group identity and belonging among users of a particular slang.

- They were (or are) primarily used by marginalised communities, and also often (but not always) related to criminal or covert activity.

- They were (or are) not languages as such because they did not evolve their own syntax. They have, however, forged distinct lexicons.

- Words were (or are) imported from other languages, common words were given new meanings and existing words were transformed by, for example, truncating them and changing the order of the sounds and syllables.

- Initially, mainstream society was either unaware of these slang varieties or regarded them with disdain, reflecting the low regard with which speakers of these varieities were held in the wider community.

- Attitudes towards these slang varieties have changed, in part, because they have featured in the arts and media. One of the indicators of the greater acceptance and even embracing of these varieties is that some of the words have entered common usage. This wider exposure undermined one of the main functions of these varieties, to allow speakers to communicate covertly.

2 What differences did you identify between Polari, Lunfardo and argot? Make a note of them in this box.

Answer

- There are clear differences in the specifics of the three slang varieties – they originated in different places and among different sections of society. Unsurprisingly, they drew their lexicon from different languages.

- The main generalisable difference between them seems to lie in their relative vitality. Polari, for example, has now become an interesting footnote in linguistic history in contrast to argot which continues to evolve. A slang variety’s robustness seems to be related to the degree to which sections of the community that use that variety continue to feel suppressed. So, in the UK, generally more liberal attitudes towards the gay community and a radically altered legal status may have contributed to Polari’s demise. On the other hand, the immigrant communities in the suburbs of French cities still largely feel excluded from the mainstream, which is one reason why French argot continues to evolve.

3.2.3 The purpose of slang

Tom McArthur is the author of numerous works on the English language, including the Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language, from which the following extract is taken.

Reading 3 Why people use slang

The aim of using slang is seldom the exchange of information. More often, slang serves social purposes: to identify members of a group, to change the level of discourse in the direction of informality, to oppose established authority. Sharing and maintaining a constantly changing slang vocabulary aids group solidarity and serves to include and exclude members. Slang is the linguistic equivalent of fashion and serves much the same purpose. Like stylish clothing and modes of popular entertainment, effective slang must be new, appealing, and able to gain acceptance in a group quickly. Nothing is more damaging to status in the group than using old slang. Counterculture or counter-establishment groups often find a common vocabulary unknown outside the group a useful way to keep information secret or mysterious. Slang is typically cultivated among people in society who have little real political power (like adolescents, college students, and enlisted personnel in the military) or who have reason to hide from people in authority what they know or do (like gamblers, drug addicts, and prisoners).

Activity 19

Does McArthur’s account add anything about the forms and functions of slang which are not mentioned by the previous three speakers discussing Polari, Lunfardo and argot?

Answer

McArthur’s account discusses fashion, which was not mentioned by the three speakers you listened to in Activity 18. For a slang to retain its vitality and social purchase, it needs to be continuously evolving. This is true of all language but particularly so of countercultural slangs.

The jargons associated with certain professions and activities, like the varieties of slang featured so far in this section, serve to reinforce a sense of group identity. In the next activity you will listen to an interview in which Nigel White, who teaches intercultural communication skills, discusses his first career, in the City of London’s financial district.

A head and shoulders photograph of Nigel White, smiling and wearing glasses, a trimmed grey beard and an open-necked blue shirt.

Activity 20

Listen to the interview with Nigel White, then answer the questions that follow.

Transcript: Broker culture

1 Write a few words about how Nigel White characterises the language of:

- city brokers

- pharmaceutical workers

- website developers.

Answer

Nigel White characterises the language of city brokers as obscene and aggressive; pharmaceutical workers as far more polite and website developers as ‘different’ in terms of language, tone and speed.

Nigel doesn’t explicitly state how website developers’ language is different in tone and speed, but one would guess that the nature of the job would allow more time for reflection than a city broker’s would, suggesting that the tone and speed are more gentle.

2 The descriptions of Polari, Lunfardo and argot that you heard in Activity 18 focused on their respective origins. What does Nigel White focus on in his description of the language of the different sectors he mentions?

Answer

Nigel’s focus is not on the words used by his fellow workers in the City, with the exception of the swearwords he alludes to. When describing the brokers’ language and that of the other sectors he mentions, he concentrates on their communicative style rather than the specific words they use. This indicates that adopting a group’s mode of communication involves more than merely learning its specialist vocabulary.

This is a photograph of a City trader, on the phone, gesturing dramatically.

In the next part of this section you will look more closely at how language is used in the workplace and at what point specialist terminology becomes jargon.

3.3 Language and profession

The reasons for using words that outsiders may not understand are not necessarily related to a need to keep people in the dark or to assert group identity. In most areas of human activity, the use of specialist vocabulary may be needed in order to refer to specific concepts that everyday language would not be able to express as concisely or accurately. Many professions have developed their own specialist terminology. The glossary that accompanies this course, for example, aims to help you to develop the terminology required in order to talk about linguistic and cultural matters in a more precise way. A professional with good communication skills is aware of the appropriate register to use with each target audience, and adjusts the amount of specialist terminology accordingly.

3.3.1 Same term, different meanings

In the next activity you will watch a video featuring Jan Grothusen, chief executive of an engineering company called Guidance, in which he talks about the potential pitfalls of using particular specialist terms with a member of a different profession.

Activity 21

Watch the video and then complete the drag-and-drop activity that follows.

Transcript: Specialist terminology and jargon

Taking into account what Jan says and your own understanding of the term, match each meaning of the word ‘target’ to the person who would be most likely to use the word with that meaning.

An object that you locate and track

Jan Grothusen

An object that you shoot at

Jan’s customer, who has a military background

A goal

A lay person, using everyday language

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 3 items in each list.

An object that you locate and track

An object that you shoot at

A goal

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.A lay person, using everyday language

b.Jan’s customer, who has a military background

c.Jan Grothusen

- 1 = c,

- 2 = b,

- 3 = a

Discussion

In its everyday sense, ‘target’ is used metaphorically rather than literally.

As you can see, the connotations of the word ‘target’ are completely different in engineering, military and business contexts. In many instances words which have an everyday meaning also have a specialist meaning in other contexts.

3.3.2 Adapting to your audience

When specialists talk about their field they may tend to use technical language that can only be understood by other specialists. Being aware of your audience’s background and adapting your language accordingly is an important communication skill.

Activity 22

This is a photograph showing a CyScan navigating device on a ship. An oilrig is visible in the background.

Now listen to another Guidance employee, Łukasz Gawryluk, describing the function of one of the company’s products, CyScan, and answer the questions below.

Transcript: CyScan (Part 1)

a.

Lay people with an interest in the company’s activities.

b.

Potential buyers of the product in question.

c.

Engineers who design similar products.

The correct answer is b.

Discussion

The description is probably too technical for people who are not familiar at all with navigation systems. A potential buyer is likely to have a need for such a product and therefore be familiar with the ways in which oil rigs, vessels and ‘DP systems’ relate to each other. An explanation aimed at an engineer would probably contain even more detailed technical specifications.

2 Based on Łukasz’s description of the product, what questions would you ask in order to fully understand what it is used for?

Answer

Here are some questions you could ask about CyScan, though you may have thought of different ones.

- What is its main purpose?

- Where does it measure the range and bearing from?

- What are DP systems?

Note:

A DP (dynamic positioning) system is a computer-controlled means of maintaining a vessel’s position. You might also want to clarify particular terminology in order to check your understanding, e.g. does ‘bearing’ mean direction in this case? Does ‘data string’ mean information?

Activity 23

Listen again to Łukasz and answer the question below.

Transcript: CyScan (Part 2)

a.

Lay people with an interest in the company’s activities.

b.

Potential buyers of the product in question.

c.

Engineers who design similar products.

The correct answer is a.

Discussion

The function of the product is now clearer: it ensures that vessels do not collide with the oil rig. The first explanation shows that terminology is only one challenge for the non-specialist. Technical descriptions often presuppose knowledge which a member of the public does not possess.

3.3.3 Jargon

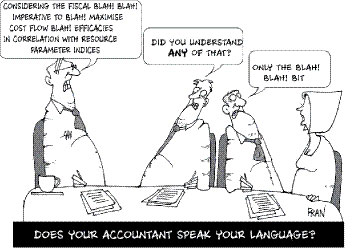

Every profession has its own terminology, but it is only meant to be used with people who are able to understand it. The use of jargon can be frustrating for those on the outside. Yet, the impulse to have an in-group way of communicating is obviously a strong one, which is why business jargon is always being developed and copied, despite being mocked or despised.

This is a cartoon featuring four people sitting at a table. One is making a long speech, including the words, ‘Considering the fiscal blah blah blah.’ One of the others is asking the person sitting next to him, ‘Did you understand any of that?’ to which the other is replying, ‘Only the blah! blah! bit’. The cartoon is captioned: ‘Does your accountant speak your language?’

Activity 24

In this activity you consider some examples of twenty-first-century ‘business-speak’.

1 The following expressions are often used in the world of commerce and finance. Match the terms to their definitions.

Test it

Run this up the flagpole

The value of something that will be lost by taking an alternative action

Opportunity cost

In future

Going forward

Look in detail

Drill down

Gradually reduce the cost of an asset in the company’s accounts

Amortise

The point at which sales equals costs

Break even

Measure of number of people who visit a venue or retail outlet

Footfall

Clearly a good idea

No-brainer

Talk about something in private

Take this offline

A cut in the market value of an asset, usually enforced by an external authority

Haircut

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 10 items in each list.

Test it

The value of something that will be lost by taking an alternative action

In future

Look in detail

Gradually reduce the cost of an asset in the company’s accounts

The point at which sales equals costs

Measure of number of people who visit a venue or retail outlet

Clearly a good idea

Talk about something in private

A cut in the market value of an asset, usually enforced by an external authority

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Haircut

b.Amortise

c.Opportunity cost

d.Drill down

e.Footfall

f.Take this offline

g.Break even

h.Going forward

i.No-brainer

j.Run this up the flagpole

- 1 = j,

- 2 = c,

- 3 = h,

- 4 = d,

- 5 = b,

- 6 = g,

- 7 = e,

- 8 = i,

- 9 = f,

- 10 = a

2 Which of these terms would you regard as legitimate business vocabulary and which do you think are unnecessary jargon? What is your rationale for deciding which are legitimate and which are unnecessary?

Answer

There is no correct answer to these questions: one person’s jargon is another’s useful specialised vocabulary. However, it is true to say that many people get irritated by business-speak phrases such as ‘going forward’ and ‘drill down’ because they do not add any meaning to their ‘everyday’ alternatives. On the other hand, take ‘amortise’ or ‘break even’; each succinctly expresses a precise meaning that takes a number of words to convey in non-specialist language and so might more easily be regarded as legitimate. Nevertheless, despite the annoyance that some language can cause, it is worth remembering that people have a natural tendency to create ‘insider’ terms when they come together with members of their family, social group or fellow professionals. This is a means of conveying membership of a particular network of people and, thus, takes us back to the important role of language in the projection of identity.

3.3.4 Features of technical language

Specialist vocabulary is not the only feature of language relating to a particular profession. Other areas of the language, such as its grammatical structures, can be affected by what it is used for and who the audience or readership is, and these are the areas on which you now focus.

Activity 25

Below are two descriptions of what a weather station does. Read them and decide:

1 (without counting) which description is longer in terms of the number of words used

2 which you think is the original description as found in an online encyclopedia (Wikipedia, n.d.).

| Version 1 | Version 2 |

|---|---|

| A weather station is a facility, either on land or sea, with instruments and equipment for observing atmospheric conditions to provide information for weather forecasts and to study the weather and climate. The measurements taken include temperature, barometric pressure, humidity, wind speed, wind direction, and precipitation amounts. Wind measurements are taken as free of other obstructions as possible, while temperature and humidity measurements are kept free from direct solar radiation, or insolation. Manual observations are taken at least once daily, while automated observations are taken at least once an hour. Weather conditions out at sea are taken by ships and buoys, which measure slightly different meteorological quantities such as sea surface, wave height, and wave period. Drifting weather buoys outnumber their moored versions by a significant amount. | A weather station is a place, on land or sea, which has equipment used by scientists to look at atmospheric conditions. This enables them to compile weather forecasts and to study the weather and climate in general. They measure things like how hot it is, how humid it is, how strong the wind is, where it is coming from and how much it rains. They have to make sure that nothing obstructs their equipment when measuring the wind and that no direct solar radiation (insolation) affects their temperature and humidity measurements. They make manual observations at least once a day, while automated ones are taken at least once an hour. Ships and buoys measure weather conditions out at sea and they quantify slightly different things, such as the temperature of the sea surface, how high waves are and how long the waves last. There are far more drifting buoys than there are moored ones. |

Answer

1 Version 2 has more words: 154 as opposed to 127.

2 Version 1 is the original text. It is taken from an entry entitled ‘weather station’ in Wikipedia (n.d.)

Activity 26

Look again at the two descriptions of a weather station and what it does, but focus specifically on the grammatical structures used and decide why one passage contains more words than the other, despite communicating the same volume of information. Make brief notes in the box below.

Answer

Primarily, the second version is longer because it contains more verbs. So, for example, it talks of ‘how much it rains’ (4 words) rather than ‘precipitation amounts’ (2 words). Another way to put this is that the first version is shorter because it contains more nouns (both ‘precipitation’ and ‘amounts’ are nouns).

Measuring the weather involves action on many levels, from the weather itself to the people and instruments doing the measuring. Yet, in Version 1 (above) many of these actions are described grammatically in terms of nouns instead of verbs. This process of turning verbs, adjectives and adverbs, such as ‘how hard the wind blows’ into a noun, ‘wind velocity’, is called nominalisation and is a common feature of scientific and academic writing.

It is noticeable in the original text (Version 1) that when verbs are used they often take a passive construction, for example ‘wind measurements are taken’ rather than ‘people take wind measurements’. You may well have heard it explained that such a construction emphasises the processes (taking measurements) rather than the agents (people). In a sense, when describing how a weather station works it doesn’t matter who takes the measurements. Such a focus also holds true in academic writing in areas of study beyond science (although styles do vary according to the discipline). Concepts and ideas are at the forefront of much academic writing (more so than the people who created them), so passive constructions are used more often than they would be in everyday communication, where the focus is usually on what people say and do.

3.3.5 Rewriting specialist phrases

In this section you will apply some of the features that you have just observed in order to practise basic report-writing techniques.

Activity 27

Imagine that you are working with data obtained from a weather station. You have the following measurements for a particular period:

- Precipitation: 15 mm

- Wind velocity: 20 km/h

- Temperature: 20 °C

1 Write three simple sentences to describe these results, using the verb ‘to be’.

Discussion

- The precipitation was 15 mm.

- The wind velocity was 20 km/h.

- The temperature was 20 °C.

2 Now rewrite the sentences using a verb other than ‘to be’.

Discussion

This is a more difficult exercise. With the first sentence, the verb ‘to rain’ cannot be used with a quantity without sounding strange. You could write something like ‘15 mm of rain fell’, turning the rain into an agent, the thing that does the action.

The second sentence could be reworded as ‘The wind blew at 20 km/h’. Again, the wind is made into a grammatical agent here.

Finally, you might write something like, ‘The temperature stood at 20 °C’.

These transformed sentences describing data sound odd precisely because they turn the weather into something animate rather than an object of study, which is at odds with the scientific context. However, in everyday conversation or in literature, we often describe the weather as if it had a will and character of its own, e.g. ‘The wind was howling through the trees’. The field of science is interested in the effect of one process on another, which requires language to depersonalise such processes by turning them into nouns.

So, particular professions not only use words and phrases that are specific to them but can also assume a particular style of communicating which, in part, is shaped by the purposes for which they use the language. This is one of the challenges that you face when entering the world of academic study. Not only do you have to learn new words and their meanings, but you also have to adopt a new way of communicating.

4 Intercultural competence at work

This section concentrates on issues arising from doing business in different languages and cultures. You will focus on a company called Guidance, a couple of whose employees you met in Section 3. Guidance has a multicultural workforce and operates in diverse markets.

4.1 Introducing Guidance

Guidance is experienced in managing the challenges of working in a multilingual and multicultural environment.

Activity 28

Watch this video in which the Guidance company is introduced by group CEO Jan Grothusen. Select any statements that apply to the company from the list below.

Transcript: Guidance (Part 1)

[cuts to colleagues talking]

a.

the oil industry

b.

the government

c.

ship builders

d.

the food processing sector

The correct answers are a, c and d.

a.

it exports goods to customers overseas

b.

it is based in a multicultural city

c.

it has an office overseas

d.

it imports goods from customers overseas

The correct answers are a, b and c.

a.

it uses recruitment agencies abroad

b.

it has close links with the university sector

c.

it recruits locally

d.

foreign employees recommend contacts and friends

The correct answers are b, c and d.

4.2 Benefits and challenges

You will now hear what the staff have to say about the benefits and challenges of working in a multicultural and multilingual company. You’ll have seen the first part of the video in Activity 28, but this is an extended version, and lasts about 15 minutes.

Activity 29

Watch the next video about Guidance and answer the three questions below by making notes in the boxes.

Transcript: Guidance (Part 2)

[cuts to colleagues talking]

[cuts to colleagues talking]

[cuts to James Grimshaw speaking on the phone]

[cuts to Alessandra Bunel speaking Portuguese on the phone]

[cuts to Portuguese class]

[cuts to Peter Paxton speaking Portuguese on the phone]

[cuts to Peter Paxton speaking Portuguese on the phone]

[cuts to Łukasz Gawryluk speaking Polish]

[cuts to Jan Grothusen speaking German on the phone]

[cuts to Alessandra Bunel speaking Portuguese on the phone]

[cuts to Portuguese class]

1 What benefits of working in a multicultural and multilingual environment do the Guidance staff list?

Answer

Guidance’s staff list the following benefits:

- it encourages ‘multicultural understanding’

- it is interesting to work with people from different backgrounds

- it allows an appreciation of other languages and cultures

- it facilitates the establishment of a rapport with clients in different countries

- it makes it easier to empathise with people from different cultures and see things from a different point of view

- it means that language skills and multicultural experience are prized by employers.

2 What are the differences in cultural working norms that the staff identify?

Answer

Guidance’s staff list the following cultural differences they have encountered:

- that the business culture in the UK is less formal and more flexible than in other countries

- they can use their bosses’ and colleagues’ first names

- that the UK working day starts and ends later than in other countries, but allows for flexible working

- that business meetings in the UK are rarely held over lunch or dinner, and that people in the UK tend not to talk about work outside their set working hours

- different rules with regard to interrupting in meetings

- different cultural practices around the giving and receiving of business cards.

3 What are the company and its staff doing to meet the challenges of doing business internationally?

Answer

Guidance uses ‘service partners’ in the regions where they do business, who understand the cultures and traditions of their clients there and can maintain a positive relationship with them. For cultural, linguistic and networking reasons they have appointed a Brazilian business development manager to tap the market in Brazil. They are sponsoring Portuguese language classes for those employees who will be involved in doing business with Brazil. This has taught them a lot about Brazil and is an important factor in building rapport with Brazilian clients.

4.2.1 A multicultural workforce

In the next activity you listen again to Sharda Bhalsod, a Guidance employee, talking about the advantages of working with colleagues from different backgrounds.

Activity 30

Look at this extract from the video you watched in Activity 29, in which Sharda Bhalsod gives her views about working in a multicultural setting. Then answer the questions below.

Transcript: Guidance (Part 3)

1. What two reasons explain why Guidance has such a multicultural workforce?

Answer

- It is based in Leicester, which is a multicultural city.

- It recruits its staff internationally.

2. What example does Sharda Bhalsod give when she says that Guidance respects individuals?

Answer

In this particular extract, she refers mostly to the company culture that encourages the celebration of different religious and cultural festivals such as Eid, Diwali, and Polish and Chinese New Year celebrations.

4.3 Doing business in different languages

Having a multilingual workforce and doing business around the world has benefits and also poses challenges. You will now begin to explore the issues arising from the use of different languages in such an environment, through the experiences of some of the people you have met in this section. Section 5 will take the subject of multilingual communication further, as you go on to consider the role of the professional translator and interpreter.

4.3.1 Using interpreters

When doing business with international partners, the lack of a shared language can be an issue. Both of the speakers in the next two videos use the term translation as they describe interpreting jobs. These two skills are often confused, and you will learn more about each of them in Activities 31 and 32.

Activity 31

In this video, Declan O’Dea, sales manager at Guidance’s international marine department, discusses the advantages and disadvantages of using plurilingual staff as interpreters to facilitate communication in international business situations.

Watch the video and complete the sentences below.

Transcript: Interpreting (Part 1)

1. The advantage of using an interpreter is that …

Answer

It enables people to understand what their interlocutor is saying.

2. The disadvantage of this approach is that …

Answer

You rely on somebody else to deliver your sales message and so you lose control of the situation.

3. One way to get around this problem is to make sure you have …

Answer

A basic knowledge of the other language, so that you can at least figure out the gist of what is being said.

Activity 32

You will now watch another account of an experience involving language mediation, this time from the perspective of the person doing the interpreting. Alessandra Bunel is a business development manager who occasionally also acts as an ad-hoc interpreter. Watch the video and answer the question below.

Transcript: Interpreting (Part 2)

In what way do the challenges described by Alessandra Bunel differ from those mentioned by Declan O’Dea in the previous step?

Answer

While Declan O’Dea considered the potential impact of mediation on sales, Alessandra Bunel’s concerns are principally related to safety. She also mentions the added difficulty resulting from the Brazilians’ habit of talking at the same time as each other.

4.3.2 Using a shared language

At the time of writing, English is the default language of international communication, especially in the field of business. When communicating with people with different first languages, native speakers of English need to bear certain considerations in mind.

Activity 33

You will now listen to Nigel White, who you first encountered in Activity 20, when he described his experiences of working as a broker in the City of London. He now specialises in intercultural training for a company called Canning. In this interview, he talks about the responsibilities that speakers have when operating internationally. Listen to the audio clip and answer the questions below.

Transcript: Communication in the business world

Decide if the following statements are true or false.

Nigel recommends that ...

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Discussion

Nigel says that native speakers shouldn’t avoid ‘all colour’ but need to be aware of idiomatic language which non-native speakers might find difficult.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Discussion

This has the added advantage of allowing more thinking time for the non-native speaker interlocutor.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Discussion

This is something he mentions. However, it needs to be remembered that not all non-native speaker mistakes come from first-language interference.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Discussion

Although there is the danger this might get a bit irritating, it is important for smooth communication.

4.4 Doing business in different cultures

So far, the issues that have been discussed in this course have focused primarily on the use of different languages in a business context. However, doing business in international settings is not only about linguistic differences and closing language gaps: cultural differences, something already alluded to by some of the staff at Guidance, can raise just as many issues and are often more difficult to identify and understand.

Activity 34

Watch this video, which is an extract from the one you saw in Activity 29, and features four Guidance staff talking about the differences in cultural expectations and behaviour between the UK and other countries they have worked in. Then answer the questions below.

Transcript: Cultural expectations

List the examples of countries and behaviours that they mention, dividing their observations into the following areas.

1. Attitudes to time:

Answer

- In Poland, the working day starts and finishes earlier.

- People have longer working hours in China, and may hold business meetings over lunch or dinner.

2. Attitudes to hierarchy:

Answer

Poland, Pakistan and Italy are more formal than the UK. More formal forms of address for colleagues and bosses are used in all three countries.

3. Attitudes to turn-taking at meetings:

Answer

In Italy it is more acceptable to interrupt each other than in the UK.

4. Attitudes to mixing business and personal life:

Answer

In China it is more common to discuss business outside working hours and to have business meetings over dinner or lunch.

The Guidance employees’ responses show that attitudes and behaviour in different cultures are not always straightforward or predictable. For example, although Italian workplaces are more formal than in the UK in some ways, people are more likely to interrupt each other in meetings.

Remember that supposed characteristics of national behaviour are not absolute and that generalisations of this sort are always potentially risky.

4.4.1 Managing diversity

Diversity is an asset but, as you have just seen in Activity 34, people’s understanding of what constitutes acceptable behaviour at work can differ from one culture to another. So how can staff from different cultures learn to work together?

Activity 35

In this next audio clip, Nigel White discusses recognising differences in any working relationship. He talks specifically from the perspective of someone helping to facilitate a merger between two companies from very different cultural backgrounds. Listen to the audio and complete the task below.

Transcript: Recognising differences

Summarise Nigel White’s key message in one sentence.

Answer

Here is one possible answer:

Recognise differences but try to accommodate to them.

In this section, through the example of Guidance Navigation, you have seen how a company can learn to work in a multicultural and multilingual environment, and how this benefits the organisation in terms of its flexibility and potential to innovate. However, it also means that employees have to learn to accommodate different behaviours and adapt their approaches and language use accordingly.

5 Translation and interpreting