Unit 1: Leadership skills required for safeguarding

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Leadership in Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector |

| Book: | Unit 1: Leadership skills required for safeguarding |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 4 March 2026, 3:58 PM |

Table of contents

- Introduction

- 1.1 What’s this course about?

- 1.2 Meet the authors, educators and mentors

- 1.3 Learning on this course

- 1.4 Keeping safe on this course

- 1.5 What do you already know?

- 1.6 The issue of leadership in safeguarding

- 1.7 What do we know about effective leadership?

- 1.8 Leadership styles: the case for feminist leadership

- 1.9 Safeguarding leadership in action

- 1.10 Equality, diversity and inclusion – questioning stereotypes

- 1.11 How to build a team to improve organisational safeguarding

- 1.12 The role of supervision

- 1.13 Developing a safeguarding culture through creating safe spaces

- 1.14 Organisational stress and burnout

- 1.15 Wellbeing

- 1.16 Empathy

- 1.17 Unit 1 Knowledge check

- 1.18 Review of Unit 1

Introduction

Welcome to Leadership in Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector. This is the third course in a series of three safeguarding courses that were first offered on FutureLearn as Mass Open Online Courses (MOOCs). This is why some of the videos you’ll watch on this course refer to these courses as MOOCs.

These MOOCs have been adapted for learning on OpenLearn Create in order to be available for study at any time, in any place and at your pace – thereby providing great flexibility. The course consists of 8 hours of learning material, split into approximately 2 hours of learning per unit, plus time to view the recorded webinars.

Another difference is that on FutureLearn the courses were offered at set presentation times with facilitated forums. On OpenLearn Create the facilitated forums are not available because of the flexibility of start dates that are offered. But some the discussions and learning from those facilitated forums have been integrated into this OpenLearn Create course through activities and enhanced teaching content.

Course 1: Introduction to Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector and Course 2: Implementing Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector have already been hugely successful in engaging practitioners globally to improve their understanding, knowledge and skills.

1.1 What’s this course about?

![]()

Watch the video above where Jan Webb, Lead Academic, welcomes you to this course and gives you an overview of its content and approach. Please note that the live webinars referred to in this video were recorded and are available on this course.

This third course explores the importance of leadership in safeguarding, both within and across organisations working in the development and humanitarian sectors. It has been designed for learners who have a responsibility for shaping and delivering the vision and strategy of an organisation. This would include managers, senior managers, team leaders, Board members, and trustees in private, public or non-governmental organisations that work in the international or national aid sector.

It provides a mixture of theory, practical applications using case studies, and examples of good practice to support you to critically reflect on your role and responsibility as a leader.

Webinars

The learning material on the course is supported by three recorded webinars featuring a range of speakers in leadership positions.

Learning outcomes

This course has been developed for learners who are in managerial, leadership and governance positions in national and international organisations working with vulnerable communities.

On completion of the course, you will be able to:

- Improve personalised approaches to safeguarding and embed evidence-based and culturally sensitive ways of working.

- Critically reflect on personal leadership skills using different frameworks and tools to embed a safe organisational culture.

- Develop learning on good practice on safer reporting and responding in order to improve accountability.

- Implement good governance with a clear senior oversight of organisational safeguarding.

The outline of the course content is shown in the diagram below.

1.2 Meet the authors, educators and mentors

This course has been created by The Open University in partnership with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in the UK.

It draws on the experience and expertise of practitioners and academics in the international development sector.

Meet the authors and educators:

Aneeta Williams is an international human rights lawyer and expert in safeguarding children and vulnerable adults, gender and sexual violence, and human rights and IHL in the international aid sector.

Janet Webb is the Associate Head of School for Nursing and Health Professions at The Open University and has extensive experience of teaching and developing safeguarding and child protection courses.

Susan Fawssett is an Open University tutor and a seasoned development researcher. She works extensively with international development organisations to deliver training and author teaching materials.

Andy Rixon is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Health Wellbeing and Social Care at The Open University, specialising in children, young people, and families. Andy has a background as a social worker.

1.3 Learning on this course

How to get the best out of some of the features of this course

Throughout the course, you will come across links to external web pages that navigate you away from this course. It is recommended that you hold down the Ctrl button on your keyboard and click on the link with your mouse to open the web page in a new browser tab.

In this way, you can keep your course open in one tab and view the new content in a separate tab.

The course will also contain learning resources and tools that can be downloaded as you progress that will assist you in learning and implementing the process. You can easily find the tools and templates for each unit under the blue contents bar.

There is an opportunity to obtain a free Statement of Participation and Digital badge at the end of the course. You will need to read through every page of the course and score 80% or above in the quizzes to receive the badge and statement of participation.

|

Learning journal To enhance your learning, you are asked to keep a learning journal as you progress through this course. This way, you can make notes on:

Your learning journal is personal to you, and it should be useful to you. You may want to share parts of it with a friend or colleague. There are no rules for keeping a learning journal – some days you may write a great deal, and at other times only a little. However, you are advised to write notes in such a way that you can understand them later. This is because we see this course as a starting point for your professional development. There are lots of practical ideas for you to try and we hope you will keep practising the techniques that you learn. In this way, you will have a reference to the things you have learnt even when you are away from a computer. You can keep your journal in a format that appeals to you and is easy for you to maintain – it could be an ordinary paper notebook or on a desktop or mobile device. You may find My Learning Journal useful as a starter document (Word) to record your notes. |

1.4 Keeping safe on this course

The themes and content of this course can inevitably be disturbing to learners. It is important that you are prepared for this, particularly when you watch or listen to the audio and visual materials.

Remember:

- Safeguarding is an emotive topic, which may give rise to feelings such as shock, anger or sadness.

- It is important to manage your own feelings so that you are able to act appropriately, professionally and in the best interests of the survivor/victims(s).

- Studying a course such as this can bring up painful memories from our own past, and this is something you need to be aware of from the start. Should this be the case as you progress through the course, please ensure that you seek support from the resources and support available to you within your organisation or seek professional help (if available).

1.5 What do you already know?

We would like to capture your knowledge, expertise and experience before you start this course.

It’s important to us as the authoring team to capture what you already know, your motivation for doing this course and your confidence level when going into this course to ensure the content is appropriate to its intended learners.

This pre-course survey will only take about five minutes to complete. It’s also really important that you complete the course and provide your feedback in the post-course survey at the end of Unit 4, so that we can continually improve the course.

Your feedback will help the project team gauge if this course has made any difference to your knowledge, skills, practice or your confidence level, but please don’t worry – all responses are anonymised so we will not be able to know or identify individual respondents.

Thank you in advance!

1.6 The issue of leadership in safeguarding

The last two decades have seen many high-profile safeguarding scandals affecting aid agencies, where those in leadership positions have perpetrated sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment (SEAH) on beneficiaries and staff.

Numerous parliamentary, external and internal enquiries have followed, which have highlighted how leaders of these organisations publicly had to apologise and/or resign from their positions for their failing to prevent, report or respond appropriately to safeguarding concerns.

Reports on a number of failings by major charities (mainly in the Northern Hemisphere) have pointed to some of the main issues. These short extracts below, from UK-based organisations, illustrate just a few of them:

“The Inquiry also heard from one member of staff that ‘it was enormously challenging to win management time’ and that staff raised almost every criticism to our leaders directly and repeatedly and they were consistently ignored until there was a bottom line - for me, this is what it means ‘not to prioritise’ Safeguarding and PSEA.” (Oxfam Inquiry, Charity Commission Report, 2019, para 20)

Source: Statement of the Results of an Inquiry: Oxfam

“This case demonstrates the damage that can be done when a charity’s internal culture and leadership behaviours appear to be at odds with the high ideals of its mission…

While the Inquiry accepts that the charity’s leadership was motivated by what they saw as correcting inaccuracies and protecting the charity’s reputation, their actions at the time created the impression, both to those who had raised concerns and to the Charity Commission, that the charity was seeking to downplay the seriousness of the allegations and was not dealing responsibly and openly with the issues.” (Save the Children Inquiry, 2020, pp. 21-31)

Source: Statement of the Results of an Inquiry: The Save the Children Fund (Save the Children U)

While these events have generated a lot of activity in the sector and commitments to improve safeguarding processes and practices, more recent reports suggest that despite these efforts the issue remains a deeply entrenched one and more progress still needs to be made.

“Although aid organisations have taken many welcome steps to raise awareness and combat sexual exploitation and abuse, the changes have focused on strengthening weak practices and policy development rather than transforming the power dynamics and enabling culture that have been embedded in the aid sector.” (www.parliament.uk, 2021, para 20)

Source: Progress on tackling the sexual exploitation and abuse of aid beneficiaries

This course is an opportunity for those in leadership positions to think about how to transform those power dynamics and how a culture that allowed harmful practices was allowed to prevail in the first place.

|

Activity 1.1 Learning from the past From your knowledge of the sex scandals and reports of misconduct in aid agencies, what are the main failings in leadership that have been identified from the various inquiries? What lessons have been learnt or could be learnt for your own organisation? Record some notes in your learning journal |

![]()

Want to find out more?

For further examples, follow the links below:

1.7 What do we know about effective leadership?

The Global Evidence Review of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and Sexual Harassment (SEAH) in the Aid Sector (Feather et al., 2021) notes that research into effective leadership in the sector is sparse. However, there are studies into effective leadership which are helpful.

|

Activity 1.2 Learning from research Read the short section on leadership in the review (Section 3.4.2 of the linked article above) and identify all the key findings. A few examples are noted below: “…Factors which may contribute to effective leadership and organisational culture include managers’ awareness of SEAH, a speak-up culture and diversity in the workforce.” “… efforts to increase knowledge and raise awareness among senior leadership in the UN had led to widespread norm change among high-level UN officials against transactional sex involving peacekeepers.” “Visible leadership by senior management was found in several studies as being an essential aspect of effective approaches to safeguarding.” “It highlighted evidence of investments in prevention efforts, which were considered to be a result of strong leadership in this area. This included investments in training and community awareness raising as well as reporting mechanisms and actions to respond to reports. One of the interviewees cited in the research, described commitment by senior leadership as the main factor which had enabled action on SEA compared to other UN missions.” Now consider these questions:

|

![]()

Want to find out more?

For more resources on leadership in safeguarding, follow the links below:

- Bond: Developing and modelling a positive safeguarding culture: A tool for leaders

- The Global Evidence Review of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse and Sexual Harassment (SEAH) in the Aid Sector (Feather et al., 2021) contains research on a range of other relevant topics such as organisational culture which you will consider in the next unit.

1.8 Leadership styles: the case for feminist leadership

There are many leadership and management styles available for organisations to adopt, but which styles or skills have a particular resonance with effective leadership in relation to safeguarding?

Research stemming from the education sector (Strachen, 1999) has identified a number of features of leadership primarily associated with women leaders, which have come to be categorised as ‘feminist’.

Definitions of what constitutes a ‘feminist leadership style’ vary, but they share some fundamental points including:

- Cooperation instead of competition.

- A belief in shared leadership.

- An emphasis on the emotional and physical wellbeing of all staff.

- An emphasis on shared power.

- A recognition of the role of power.

This last point – the recognition of the role of power – is perhaps the most important, as it means that the focus is not just on the position of women but a whole range of ways in which power is relevant in the intersection of race, social class, gender, and sexual orientation. It is also the focus on power that makes this approach to leadership so relevant to safeguarding:

Implementing a ‘feminist’ leadership style is more than simply placing more women at the top (although this is a helpful step) as it is not a guaranteed indicator that an organisation has a particular leadership style. Both men and women leaders could perpetuate patriarchal structures if they benefit from positions of power and authority or feel they need to adopt the prevailing leadership culture to be accepted and retain their positions of power.

Equally while these principles may be a greater challenge for organisations where men have historically dominated the management hierarchy it is important to stress that Men are equally capable of deploying elements of a feminist leadership style – such as sharing power and challenging their own behaviour. Labelling this collection of leadership features as feminists is therefore not intended to be divisive by setting supposedly male and female approaches to leadership against each other, it is just acknowledging the perspective from which they have arisen.

You can see slightly different versions of the ‘top principles’ of feminist leadership in the readings below, which report on how some aid organisations (including those who had been the subject of the critical reports as we have already discussed) have been exploring this idea.

|

Activity 1.3 Feminist principles and safeguarding practice. Read these three short articles of feminist leadership principles and reflect of the questions that follow. How ActionAid implemented feminist leadership principles ActionAid: How we practise feminism at work

|

![]()

Want to find out more?

For another resource on different leadership styles, follow the link below:

1.9 Safeguarding leadership in action

![]()

Watch the video above, in which we hear the voices of those in leadership positions responding to this question: What leadership skills have you used to improve safeguarding in your organisation? Reflecting on the speakers in the video are there points that might be useful for you to develop further?

You can watch Andrew Azzopardi talking in more detail about leadership in the first of the course webinars in Unit 2.

1.10 Equality, diversity and inclusion – questioning stereotypes

“At its core, SEAH is borne out of power imbalances. These power imbalances are caused by deeply entrenched systemic issues such as racism, sexism, colonialism, xenophobia, homophobia, and religious hatred, among others. Compliance measures to address SEAH are done in vain if they don’t simultaneously address these systemic issues.”

Source: InterAction CEO PSHEA pledge: 3-year update (2021)

Enhancing equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in an organisation does require challenging stereotypes and ensuring that people who represent different race, age, gender, sexuality and disability categories are represented in (senior) management with decision-making authority.

In New Study On Women In Leadership (Brower 2021), the author makes the point that the use of language is powerful in reinforcing attitudes and prejudices. Language we use may not be explicitly offensive but rather insidious and normalised. It is the role of leaders to consider how this works in an organisation and take the lead in giving the message that certain terminology is not acceptable. While this is true of all organisations it is particularly pertinent when we are thinking about safeguarding where gender is a fundamental dynamic in sexual abuse and harassment.

It is also worth challenging ourselves about whether we are allowing assumptions about leadership to work in favour of men. For example, it has been questioned by some whether ‘confidence’ – a trait more often observed in men – is more highly valued in recruitment and promotion, assuming (mistakenly) that it equates to ‘competence’ (Chamorro-Premuzic, 2013). As with other issues, such biases may be unconscious, which makes it particularly important that all our attitudes are held up for critical scrutiny.

While we have focused on gender here, this of course not the only issue in terms of representation in organisational hierarchies. You may remember from the learning surrounding the Global evidence review in that racial balance was also cited as important in relation to safeguarding:

“A number of sources highlight promoting diversity among leadership as an effective approach to addressing SEAH. The evidence identified placed a particular emphasis on the importance of gender and racial balance among senior leadership.” (Feather et al, 2021)

|

Activity 1.4 Women in leadership Now read Tracy Brower’s article New Study On Women In Leadership which highlights some of these stereotypes regarding appointing women in management and consider the question below:

|

There are many other power imbalances that would be at least in part addressed by issues of representation such as the numbers of international staff from the global south at senior levels. The importance of EDI in developing an organisational safeguarding culture and other barriers to achieving it such as racism will be a topic in Unit 2.

1.11 How to build a team to improve organisational safeguarding

Part of a being a good leader is to support your staff in finding the space in which they can grow, develop. and be appreciated for what they do.

To do so, team leaders should know about how teams grow to be functional, where trust and respect are foundational stones to this. One model of team development was proposed by Tuckman (1965) who argued that teams will go through various stages – ‘forming’, ‘storming’, ‘norming’, ‘performing’ and ‘adjourning’.

|

Activity 1.5 How to build a team Watch the video above on team development which explains these stages and the different roles that a leader can play at each of the stages and then respond to the following questions in your learning journal:

|

1.12 The role of supervision

Supervision is widely recognised as an important tool to support good professional practice across many sectors and may be a key element in helping to ensure good safeguarding practice in aid-related organisations.

It is an opportunity for a supervisor and supervisee to reflect on issues and challenges encountered in practice. It requires an environment in which staff can speak freely about the difficulties they have experienced and receive emotional support from their supervisor. While the topics discussed can be wide ranging, the practice of supervision is ideal to focus on safeguarding experiences in order to provide support and to also advance good practice.

In a supervisory relationship there are issues of both quantity and quality. Ideally, it needs to be a regular commitment and protected time. This can be difficult in demanding environments but cues on the importance of ensuring that supervision time is protected should be led from the top.

Secondly, supervision needs to be more than identifying more work or ‘checking in’. It is an opportunity to talk though issues, problems and uncertainties, and a place where safeguarding can always be on the agenda. To achieve this does require a level of skill for managers in being able to create an environment of trust – a safe space – in which the supervisee feels listened to, particularly if they have difficult experiences to share.

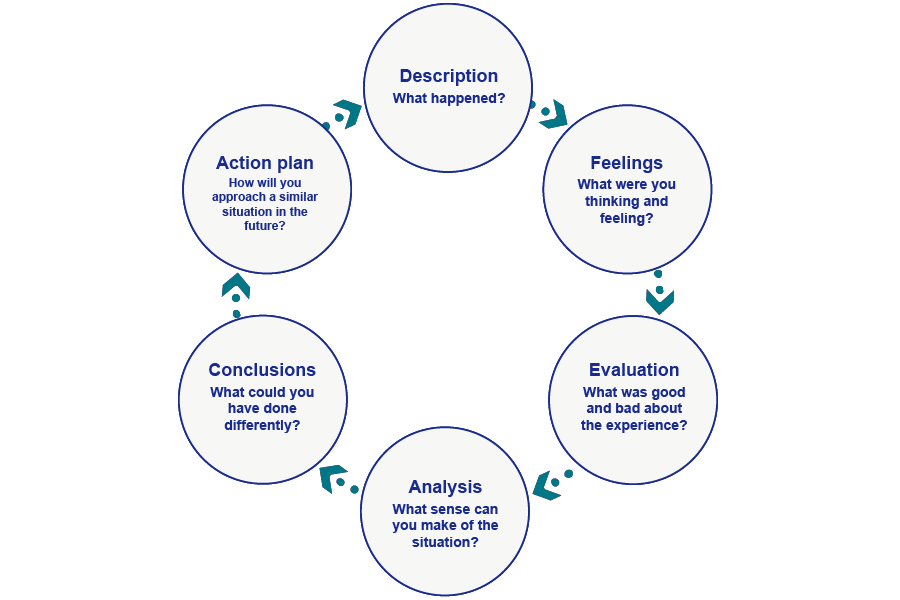

Using a reflective cycle is widely promoted as a theory to underpin the practice of supervision. This means reviewing, in a structured way, what has happened in order to derive learning that can be used to improve practice in the future. The model illustrated below (Gibbs, 1988) also includes a recognition of the impact of how people feel, given that work in the sector in general and safeguarding issues in particular, can bring up many powerful emotions.

There can be benefits from extending reflective supervision beyond the one-to-one meeting in environments where a team of people are working together. Managers can use other reflective tools like the use of a critical incident analysis to promote learning.

In a critical incident analysis, one person can present a problematic or challenging scenario they have recently encountered – for example, how they responded to a safeguarding report – and the group can help identify learning from the incident that will benefit everyone, such as the changes needed to practices or policies, and training or development needs.

This more collaborative approach is designed to enable the sharing of power where solutions and new knowledge can be jointly created.

As well as contributing to a safe working environment, supervision can also make an important contribution to staff wellbeing – the subject of a later section of this course.

|

Activity 1.6 Supervision Consider the following questions:

|

1.13 Developing a safeguarding culture through creating safe spaces

![]()

Watch the video above, in which you hear from leaders describing how they try to create safe spaces to both enable supervision and encourage staff to feel able to speak up about their concerns.

1.14 Organisational stress and burnout

“The Duty of Care is fundamental. How do we expect to care for affected populations if we’re not taking care of our own?” IVCA / CHS alliance, 2021 p7

In her article on burnout, Huffington describes the phenomena as a ‘workplace crisis’, now with its own definition from the World Health Organisation:

“A syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three key factors: feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and reduced professional efficacy.” Huffington (2019)

This article is not specifically focused on the international aid sector and research suggests that burnout rates in the sector may be two to three times higher than the general population. While this may not sound surprising, given the challenging nature of much of the work in the sector, what might be more surprising is the extent to which organisational factors contribute to this burnout.

|

Activity 1.7 Stress and the role of organisations Listen to the following audio which is part of an interview with Dr Liza Jachens who has researched this topic and consider the relevance of her conclusions to your organisation. Note any ideas in your learning journal. Listen to the second part of the audio, in which Dr Jachens also talks briefly about how organisations might respond to issues of mental health in their workforce, for example, being proactive not just reactive and challenging stigma. |

1.15 Wellbeing

In the research discussed in the previous section (Jachens 2019), the biggest contribution to stress is identified not as ‘operational stressors’ that are associated with the trauma of the direct work, but ‘organisational stressors’ deriving from other factors, such as the management and organisation of work, dealing with rapid change, conflict and bullying.

This aspect of stress is therefore amenable to intervention and change and so is very much within the remit of organisational leaders to address. In relation to safeguarding, elements of burnout listed in the definitions in the previous Section, such as mental distance and feelings of cynicism, run the risk of workers adopting unhealthy coping mechanisms or being less likely to engage in the challenging work of dealing with SEAH.

The report Leading Well (IVCA / CHS alliance, 2021) has explicitly considered this issue and in its summary the report identifies ten key practices for leaders in relation to wellbeing:

- Modelling self-care.

- Openly discussing mental health with staff.

- Recognising the contributions of others.

- Challenging inappropriate behaviour.

- Using their position responsibly and fairly.

- Actively listening to different perspectives.

- Communicating consistently and with authenticity.

- Prioritising the workload.

- Giving people space to do their jobs.

- Cultivating caring, compassionate organisational cultures.

The second part of Leading Well contains the more detailed views and reflections of organisational leaders in the field on the challenges and potential ways forward in creating a supportive workplace culture focused on wellbeing.

|

Activity 1.8 Wellbeing and stress Read Leading Well Part 2 and the conclusion, and then consider the following questions using your learning journal. :

|

1.16 Empathy

Another key word associated with the leadership style being explored here is ‘empathy’ and its potential contribution to improving the safety and wellbeing of beneficiaries by improving the safety and wellbeing of staff.

Workers in the development sector may witness many traumatic things and the safeguarding issues we are focusing on here can certainly be extremely difficult and emotional. Abuse of children or sexual aggression to adults is always disturbing and, in some cases, will be truly shocking. This is perhaps amplified by the fact that harm has been perpetrated by representatives if not colleagues in the agency they represent. What responses do such workers deserve? What support do they get?

In fact, the value of empathy in management and leadership is being highlighted in the wider organisational and business world. The following article concludes that:

“Empathy contributes to positive relationships and organizational cultures, and it also drives results. Empathy may not be a brand-new skill, but it has a new level of importance, and the fresh research makes it especially clear how empathy is the leadership competency to develop and demonstrate now and in the future of work.”

Read (or listen to) the whole of this brief article Empathy is the most important leadership skill according to research.

|

Why is an emphasis on empathy particularly congruent with leaders working to enable a safeguarding culture in their organisations? |

1.17 Unit 1 Knowledge check

The end-of-unit knowledge check is a great way to check your understanding of what you have learnt.

There are five questions, and you can have up to 3 attempts at each question depending on the question type. The quizzes at the end of each unit count towards achieving your Digital Badge for the course. You must score at least 80% in each quiz to achieve the Statement of Participation and Digital Badge.

1.18 Review of Unit 1

This unit has explored the nature of leadership and some of the ways in which those at the top of their organisations can think about elements and styles of leadership that might further enhance safeguarding.

We have explored in particular the importance of considering issues of power and the broader wellbeing of staff. This will continue into the next unit where you will look in more detail at the importance of organisational cultures.

|

From any of the readings, discussions or videos in this unit, try and identify three things that you might take away from unit 1 of the course in relation to leadership. |

Now go to Unit 2: The importance of a safe organisational culture.

References

Brower, T. (2021) New study on Women in leadership: Good News, Bad News and The Way Forward [Online]. Available at Forbes.

Brower, T. (2021) Empathy Is the most important leadership skill according to research [Online]. Available at Forbes.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2013) Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? [Online]. Available at Harvard Business Review.

Charity Commission for England and Wales (2020) Statement of the Results of an Inquiry: The Save the Children Fund [Online]. Available at Gov.uk.

Charity Commission for England and Wales (2019) Statement of the Results of an Inquiry: Oxfam [Online]. Available at Gov.uk.

CHS Alliance/ICVA (2021) Leading Well: Aid leader perspectives on staff wellbeing and organisational culture [Online]. Available at CHS Alliance/Leading Well.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods, Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic, Oxford.

Feather, J., Martin, R., and Neville, S. (2021) Global Evidence Review of SEAH in the Aid Sector [Online]. Available at RSH Resource & Support Hub.

Huffington, A. (2019) Burnout is Now Officially a Workplace Crisis [Online]. Available at Thrive Global.

Jachens, L. (2019) Humanitarian Aid Workers’ Mental Health and Duty of Care, Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(4), pp. 650–655.

Strachan, J. (1999) Feminist Educational Leadership in a New Zealand Neo-Liberal Context, Journal of Educational Administration, 37(2), pp. 121–138.

Tuckman, B. (1965) Developmental sequence in small groups, Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), pp 384–399.