Disruption and design

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | The online educator: People and pedagogy |

| Book: | Disruption and design |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 February 2026, 10:27 AM |

Description

Myths, hype and reality in online education

Myths, hype and reality in online education

The fast-changing online education landscape is buzzing with hype about 'disruptive innovation' that will radically transform teaching and learning. What's being claimed? Which innovations will last? How do we know?

The fast-changing online education landscape is buzzing with hype about 'disruptive innovation' that will radically transform teaching and learning. What's being claimed? Which innovations will last? How do we know?

1.1 Who are the students?

Welcome to The Online Educator: people and pedagogy. I’m Dr Leigh-Anne Perryman – an academic with The Open University (OU). In the first three weeks of this course I’ll be drawing on my experience as an educator and a researcher as I introduce some of the hype around online education, some of the ways in which educators can navigate that hype, and strategies for designing engaging online learning experiences.

Over the coming weeks you’ll closely examine several myths connected with online education as the basis for making your own decisions about how to employ innovation in your teaching.

This week, you’ll start by investigating the notion that online education is a ‘disruptive’ solution to a broken education system. Then you’ll explore ways to create engaging and relevant learning experiences that make good use of innovative technologies and pedagogies to meet learners’ needs. You’ll be introduced to the use of personas in learning design and and look at the steps involved in designing a successful online learning experience.

In Week 2, you’ll discover ways to make innovative learning accessible to all and the relationship between accessibility and innovation. You’ll also consider the importance of inclusion in online education.

In Week 3, you’ll explore strategies to evaluate claims about the transformative impact of online education, such as those made in research reports. You’ll also investigate ways to reflect on your own teaching in order to assess the impact of educational innovation, including consideration of the ethical issues involved in researching online learning.

In Week 4 I’ll hand over to ed-tech celebrity and Open University emeritus professor, Professor Martin Weller. He’ll take you through a study of the benefits and complexities of constructing an online identity as an educator, and the importance of considering the wellbeing of everyone involved in online education.

First though, watch the video above and step into the future of education… It’s full of technological innovation. Teaching and learning have improved immeasurably. Everybody is included. Does this sound too good to be true?

The video was made by Educause – a nonprofit association whose mission is ‘advancing the strategic use of technology and data to further the promise of higher education’. It gives you a flavour of some of the claims that have been made about the online education of the future. In this case, they are claims that were being made when the video was released in 2017.

As you watch, consider the following:

- Have any of the predictions come true already?

- Do you believe the predictions being made will all come true? If so, why? If not, why not?

- Did the video creators miss anything out?

- Do you feel excited about any of the possibilities?

1.2 Studying this course

Leigh-Anne Perryman introduces the course authors

Martin Weller and I have been involved in educational technology for many years. We each bring our own diverse experiences and interests to this course.

I’m the Qualification Director for The Open University’s Masters in Online Teaching. I’ve been an educator for over 20 years and have taught in the arts and education disciplines, in both the further and higher education sectors. I began teaching online when online learning was still in its infancy. My research focuses on openness in education, and the ways in which open educational resources and practices can increase access to quality learning in the developing world. I’m particularly interested in women’s empowerment through open education, as well as the ethics of online research. I’ll be drawing on my teaching and research in Weeks 1, 2 and 3.

Martin Weller is Emeritus Professor of Educational Technology at The Open University. For many years he was Director of the OER Hub research team, leading a portfolio of projects examining the impact of open educational practices. Martin’s main research has been in open education and digital scholarship. He blogs about this at The Ed Techie, and has authored several books that are available under open licence. Martin will be drawing on his own experiences as a digital scholar and blogger in his exploration of online educator identity in Week 4.

You’ll meet both Martin and I as the course progresses, as well as the facilitator, who will respond to your comments and questions.

Introduction to OpenLearn Create

OpenLearn Create is an innovative leading open educational platform where individuals and organisations can publish their open content, open courses and resources. It is a Moodle platform and has tools for collaboration, reuse and remixing. OpenLearn Create sits alongside OpenLearn where the OU hosts specially designed open content, giving everyone the opportunity to browse, reuse and learn across a world of open learning.

While OpenLearn hosts only OU content, the projects, content, courses and resources within OpenLearn Create come from a range of providers, not only The Open University, giving you access to rich and varied content that you can study, reuse and remix.

OpenLearn Create FAQ

Statement of Participation

A Statement of Participation will be available upon successfully meeting all course requirements, including scoring at least 40% on each end-of-week quiz and 70% on the end-of-course test.

1.3 Myth: disruptive innovation can 'fix' education

‘Innovation’ – creating or trying something new – is a term that is frequently used in the rapidly changing field of educational technology. For an online educator, innovation might involve trying a new technology or teaching method. It might also involve applying an existing technology or teaching method to a new context.

Innovative online educators who want to enhance their teaching need to navigate some bold claims about online education’s transformative power as a force for good. Innovation in online teaching is often framed within an ‘education is broken’ narrative that has become widespread, especially in the US. Farrow (2015) notes that ‘analyses which emphasize a state of crisis in education are often accompanied by the idea of some sort of salvation through technology’ in the form of disruptive innovation.

The term ‘disruptive innovation’, coined by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen in 1995, has its roots in business administration. It has since been appropriated by educational technologists and commentators to represent the replacement of ‘stale’, traditional models of teaching and learning with more effective practices – an ‘educational apocalypse’ that will change teaching and learning forever.

MOOCs – ‘massive open online courses’ that are free to study, accessible to all, and typically attract large numbers of learners – were frequently the object of this type of discussion. Speaking at the 2012 Digital Life, Design conference Udacity’s founder Sebastian Thrun, recalled being ‘blown away’ by the mass engagement with open education made possible by the Khan Academy, suggesting that education could change the world.

A year later, in 2013, Clayton Christensen gave an interview at the Startup Grind global event and made a prediction that seems increasingly unlikely to come true - that by 2028 over half of universities would be bankrupt due to innovations in educational technology – a prospect he said he was excited about.

In 2023, the claim was repeated (with some scepticism) by Baroness Kidron in the UK Parliament:

For more than a decade, Silicon Valley, with its ecosystem of industry-financed NGOs, academics and think tanks, has promised that edtech would transform education, claiming that personalised learning would supercharge children’s achievements and learning data would empower teachers, and even that tech might in some places replace teachers or reach students who might otherwise not be taught (Hansard, 2023).

Many people have challenged the idea that education is ‘broken’, and that disruption is its salvation. Martin Weller voiced three reservations:

i) It’s just lazy – saying something is broken (or dead) avoids having to do any subtle analysis and appeals to a simplistic viewpoint.

ii) It frames technological change as a crisis and not an opportunity… a negative problem to be fixed.

iii) It’s suspicious – those who peddle the “education is broken” line usually have something to gain from its acceptance. Either they are directly selling a solution that will mend it… or they have individual prestige in being seen as someone who can at least see the means of fixing it.

The notion of disruptive innovation as a force for good has proved to be enduring in education. It underpins many of the claims that are made about developments in educational technology. However, the idea also has its detractors, including technology journalist Audrey Watters, who identifies it as a myth. Next, you’ll explore Watters’s views and consider whether online teaching really is education’s saviour.

© The Open University. © The Ed Techie (2012) Education In ‘Not Broken’ Shock, 5 December 2012. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

1.4 Will online teaching and learning be education's saviour?

A desert wasteland impacted by fire

© Gus This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/

Edtech journalist Audrey Watters has written much about the ‘myth’ of disruptive education and the narrative of an ‘education apocalypse’. In December 2017, she summarised the year’s edtech developments:

Some of the most oft-told tales in education in recent years have the following plot: the students all move from “brick-and-mortar” to “online.” It’s an inevitable move, or so the story goes.

Clayton Christensen and Michael Horn, for example, predicted in their 2008 book Disrupting Class that by 2019 half of all high school classes would be taught via the Internet. There was all that ink spilled circa 2010 that Khan Academy and “flipped learning” were going to “change the rules of education,” replacing in-class instruction with online videos watched as homework. And then there were MOOCs, of course, and all those predictions and all those promises about the end of college as we know it: “MOOCs make education borderless, gender-blind, race-blind, class-blind and bank account-blind” and similar fables.

It’s not simply that the predictions were wrong. (Although no, to be clear, we are not on track for half of high school classes to be online or for higher education to be replaced by Udacity, and no, MOOCs have not transformed higher ed into some magical meritocracy.)

Rather, it’s that the steady drumbeat of stories about the inevitability of online education has shaped the cultural imaginary. It has shaped the political imaginary. It has shaped the administrative imaginary – and that in turn has shaped how schools have built capacity (or much more likely outsourced capacity) and defined capacity altogether – notably in response to what’s been consistently framed as the challenge of access and the necessity of choice.

Online education, we’re still told, will be education’s disruptor. Online education, we’re also still told, will be its saviour.

Discussion

Reflect on what you know about how online education was used during the Covid lockdowns and how it has been used since then.

- Has online education been education’s saviour?

- Does it offer more desirable choices?

- Which innovations will really disrupt education in a lasting and positive way?

- Can innovation benefit some, while disadvantaging others?

Use the discussion area to share your thoughts and experiences with your fellow learners.

© The Open University / Audrey Watters (CC-BY)

1.5 Different realities

One technology that is often described as a potential disruptor is virtual reality (VR). This ‘reality’ is computer generated and often experienced using a headset. It provides a three-dimensional environment that users can interact with – for example, they can move through a landscape, use tools, or talk to other people. Since the late twentieth century, people have been exploring its use in education.

VR can provide students with opportunities to experience things that would be difficult, dangerous or impossible in day-to-day reality. They might explore the inside of a volcano, watch landscapes change over time, or perfect an emergency response technique.

In 2007, the virtual world Second Life was hailed as offering exceptional educational opportunities for learners to collaborate and interact, with the potential to fundamentally transform online learning. However, despite the initial hype and a flurry of institutions setting up virtual Second Life campuses, just a few years later commentators such as Carrie Marshall (2011), writing for TechRadar, were asking ‘whatever happened to Second Life?’.

Second Life provides an example of how a technology in use by wider society was appropriated and adopted by educators. It is also an example of a technology that was ahead of its time in terms of learners’ needs and skills. While the educational use of Second Life has greatly reduced since its heyday, virtual reality has had a lasting legacy. In 2021, it went through another period of hype, this time in the form of the Metaverse launched by the company that owns Facebook.

These days, VR is often considered together with augmented reality (AR). An AR application can be used on a phone or other device to overlay information on objects around us or on our surroundings. For example, it can overlay a reconstruction of an historic site on its surviving remnants, or it can bring up instructions on how to work a piece of machinery. Combinations of VR and AR are often referred to as extended reality (XR). Two examples of XR currently in use in education are:

Virtual field trips: The Open University uses Virtual Skiddaw to recreate the sights and sounds of a mountain in the north of England. Students are able to browse map overlays, make detailed observations of the geology, produce field sketches, examine rocks through a microscope, contrast texture and mineralogy, and describe structural features.

Safety training: In the USA, the Centre for Innovative Research in Cyberlearning is developing VR training that makes it possible for trainee construction workers to explore a hazardous environment and find out what happens if they fail to pay enough attention to safety. They experience realistic sights and sounds – and ‘haptic’ feedback recreates feelings of touch and motion.

The Open University’s Dr Rebecca Ferguson was active in researching the use of Second Life for educational purposes at the peak of interest in the platform. In the above video I interview her about the value of Second Life, the reasons for its decline in use, and about a recent resurgence of interest in virtual worlds. Note that Rebecca is sitting on the left, with a dragon on her shoulder. I’m on the right (with no pets).

As you watch, consider:

- Do you think VR, AR or XR have potential to transform online learning?

- Can you see any potential for their use in your own subject area?

1.6 Which innovation will last? (Poll)

The past ten years have seen fast-paced change in the field of online learning and the Covid lockdowns prompted many institutions to try online teaching for the first time. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of technological and pedagogical developments have been claimed as having the potential to change the shape of education as we know it.

Obviously, the impact of such developments will differ across educational sectors and subject areas. However, it’s possible that some have had a widespread effect that will guarantee them a place in the educational technology hall of fame.

This poll presents a small selection of technological and pedagogical innovations related to online learning, and asks you to vote on which you think will have the most enduring impact.

Which of the following innovations do you believe will have the most enduring impact on online education?

Put people first

Technology is often the main focus of discussions around online learning innovation. This can lead to learners' needs and preferences being overlooked. Using personas when designing learning can refocus attention onto people.

Technology is often the main focus of discussions around online learning innovation. This can lead to learners' needs and preferences being overlooked. Using personas when designing learning can refocus attention onto people.

1.7 Myth: technology is the most important aspect of online education

A network of technology and users

A network of technology and users

© From Pixabay. Covered under Creative Commons licence CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication

Many of the claims made regarding innovation in online learning focus on technology, rather than the people being taught, or the pedagogies being used by teachers. In a world of shiny new platforms, tools, apps, hardware and software it can be difficult to find out whether they are actually meeting the needs and accommodating the learning preferences of real people.

Way back in 2014 (pp. 42-50), in a keynote conference speech Engaging flexible learning, Audrey Watters voiced concern about the imbalance between technology, pedagogy and people in discussions around educational innovation, noting ‘we do spend an inordinate amount of time in education and in education technology talking about things other than learning’.

Watters acknowledged that ‘we now find ourselves in an era of remarkable potential for education’, when ‘it’s a great time to be a learner thanks in no small part to new technologies’ which ‘offer us exciting opportunities for learning new things in new ways with new people’. However, she also observed that ‘much of this exuberance for learning [is] happening in informal settings, not in formal educational institutions’. The flexibility available to people learning informally, who take control of their own learning of topics that interest them, is not available to them in formal learning settings, she argued. One reason for this is that so often technology is the driver for innovation in education; not the people, not the pedagogy.

Watters proposed that the cause is ‘technology solutionism’ – ‘the growing power of the tech industry’, and an emphasis on education ‘as a market, as an ideology, as something to automate, something to “fix’’’.

She ended her keynote:

Learning – human learning – isn’t an algorithm. The problems we face surrounding education cannot be solved simply by technology…. Education is a human endeavor – profoundly human. We cannot, we should not automate these processes with teaching machines. Because we are tasked with teaching people after all.

In the steps that follow, you’ll look at one way for online educators to ensure that people, their learners, are at the centre of online teaching – the use of personas in learning design.

© The Open University

1.8 Personas: helping educators meet learners' needs

Understanding the learners behind the screens

Designing online learning activities can feel quite daunting. There’s a wide range of resources, technologies and pedagogies available and it’s often difficult to decide which of them will benefit your learners. The practice of learning design can help online educators to incorporate new ideas in a way that is suited to their learners’ needs.

Learning design has been defined by Mor and Craft (2012) as ‘the act of devising new practices, plans of activity, resources and tools aimed at achieving particular educational aims in a given situation’. Learning design:

- provides a means of guiding the creation of activities that learners will undertake

- prompts educators to think about what they want learners to achieve while studying

- helps educators provide the context that will enable learners to achieve those outcomes

- encourages educators to take into account the diversity of those learners

- provides ways of explaining these activities so that they can be shared with other educators.

The use of personas

Using personas is an effective, non-technological, way of putting people at the centre of your teaching. Personas are used across several fields and have been used in software development and marketing for decades. The use of personas in learning design is more recent.

In education, a persona is a fictional yet realistic description of a potential learner. A persona summarises that learner’s background, geographical location, employment status, educational qualifications, personal characteristics that are relevant to their learning, abilities, experience, preferences, and motivations for study. It also outlines the challenges they face – for example, they may have caring responsiblities which mean they can only study at certain times.

Although fictional, personas can draw on your experience of real learners. Once created, they will have value both in planning new teaching and learning activities and resources, and in checking whether existing resources and learning activities will meet learners’ needs. The real value of personas, though, is during the design stage, before anyone has signed up for your course. Once a course has started you will be able to survey the actual students studying that course and then adapt teaching and learning activities as needed.

A persona is not intended to be a ‘typical’ student, but rather a non-typical student with particular characteristics that might exclude them from learning. While personas don’t cover all possible learner types, they are a prompt for thinking about the many ways in which differences between learners can be accommodated. There are no set rules about how many personas should be created. However, as an indication, we created eight personas for this course, because we knew that it was likely to attract a large and diverse group of learners.

In the next step you’ll be guided through the process of creating a persona.

© The Open University

1.9 Personas: what should they cover?

Cooper (1999) suggests personas are most effective in informing learning design if they ‘become a real person’. They should:

- Be specific: ‘The more specific we make our personas, the more effective they are as design tools’.

- Give the persona a name, ‘as without one they will never be a concrete individual in anyone’s mind’.

- Put faces to the names, to give each persona an image.

- Be precise rather than accurate.

When designing a learning activity it’s important to create several different personas to represent typical learners in your setting.

The above video takes you through the creation of a persona – Miray – devised to inform the design of a Masters-level MOOC on modern art. As you watch, consider:

- How might aspects of Miray’s persona influence the MOOC’s design?

- Might any of Miray’s characteristics be difficult to accommodate, or conflict with the needs of other learners?

- What do you think is the value of creating a persona, over just trying to design learning activities featuring a range of teaching methods and resources?

© The Open University (Assets Used: © PhotoDisc)

1.10 Persona creation in practice

Venetian mask disguise

Venetian mask disguise

© From Dreamstime. Covered under Creative Commons licence CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication

Imagine you’re planning to design a free online course such as this one, focused on developing skills in being an online educator. You want to attract learners from across the globe and you want it to be appealing and relevant to as many people as possible. You are pitching the course at Masters level in the knowledge that many education professionals, or aspiring educators, will have existing undergraduate, and maybe postgraduate qualifications.

- Use the personas template available via the link at the bottom of this page as the basis for creating one persona, representing a potential learner for your course. Give the persona a name and add some information about them.

- Now share your persona with your peers. Note just one way in which the design of your course might accommodate the needs, background or characteristics of your persona.

- Finally, comment on someone else’s persona, again suggesting a way in which the course design might accommodate their needs, background or other characteristics.

© The Open University

From people to pedagogy

Having defined personas for a course, the next step is to consider which teaching approach will best meet the needs of the people represented by those personas, helping them to achieve their learning outcomes.

Having defined personas for a course, the next step is to consider which teaching approach will best meet the needs of the people represented by those personas, helping them to achieve their learning outcomes.

1.11 Myth: focus on the technology and the pedagogy will follow

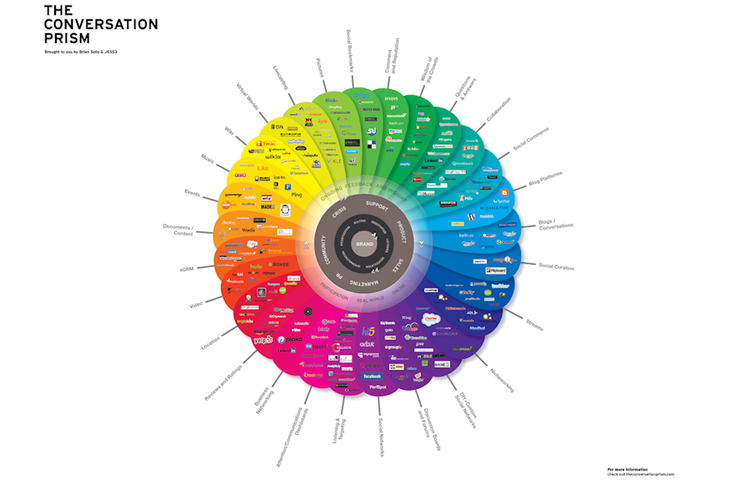

The conversation prism (long description and link to a larger version appears at the bottom of the page)

The range of technologies available to online educators is staggering. Statistics from late 2022 show that 3.5 million apps were available to Android users, and 1.6 million to Apple users. The Centre for Learning and Performance Technologies lists 100 ‘top tools’ for learning in 2023, based on a survey of 2022 learning professionals. Similar lists of ‘top tools’ are widespread. Both of these links take you to current figures.

More often than not, lists of ‘top tools’ are based on the numbers of people using these tools, rather than on an assessment of their effectiveness. In addition, discussion of pedagogies that would work with the tools, and of the tools’ relevance to specific types of learning outcome, or to learner needs and preferences, is usually absent. In 2008 Gráinne Conole commented in her article New Schemas for Mapping Pedagogies and Technologies: ‘I have a fear that because the technologies are so exciting and beguiling that we are seeing a technologically deterministic drive, rather than one based on sound pedagogies’.

The same issue was still apparent in 2024. Encouraged by the popularity of the ChatGPT tool, which uses artificial intelligence (AI) to generate convincing text, many educational institutions promised to add AI to their teaching. The focus was on the tool, rather than on how it could be used effectively, or on its benefits to the learner.

By now, you will have some idea about why technology receives more attention than pedagogy or people. You’ve already encountered what Audrey Watters terms ‘the Silicon Valley narrative’ – that education is ‘broken’ and technology will ‘fix it’ (at a price). Promoting new ‘fix education’ technologies is profitable. Evaluating those technologies’ effectiveness, and promoting new pedagogies and their use with learners, is less so.

In the final section of Week 1 you’ll consider how educators might shift focus away from technology and pay more attention to pedagogy.

© The Open University

Larger version of the infographic:

Long description

"A circular infographic titled 'The Conversation Prism,' designed by Brian Solis and JESS3, maps the social media landscape by categorizing various platforms and services. The chart has a multi-layered radial design with a gradient color scheme that differentiates distinct segments of social media.

At the center of the diagram, a core circle represents the 'Brand,' surrounded by four key focus areas: 'Marketing,' 'Community,' 'Support,' and 'Product.' Encircling these areas, an intermediate ring highlights aspects of engagement, including 'Participation,' 'Real World,' 'Listening,' 'Ongoing Feedback & Insight,' and 'Crisis Management.'

Radiating outward, the outermost ring contains individual social media categories, each represented by a petal-like segment filled with platform logos. Some of these categories include:

- Social Networking (Purple & Blue): Platforms like Facebook, LinkedIn, and MySpace.

- Microblogging (Blue): Includes Twitter and Tumblr.

- Blogs & Conversations (Blue-Green): Platforms such as WordPress and Blogger.

- Social Curation (Blue-Green): Pinterest, StumbleUpon, and Flipboard.

- Collaboration (Green): Services like Google Docs and Wikis.

- Reviews & Ratings (Red-Orange): Yelp and TripAdvisor.

- Video (Orange): YouTube, Vimeo, and Brightcove.

- Location-Based Services (Pink-Red): Foursquare, Yelp, and Plancast.

Each category groups relevant platforms, emphasizing their role in digital communication, networking, and brand interaction. The infographic provides a comprehensive overview of how brands and users engage across different social media ecosystems."

1.12 Finding out about innovative pedagogies

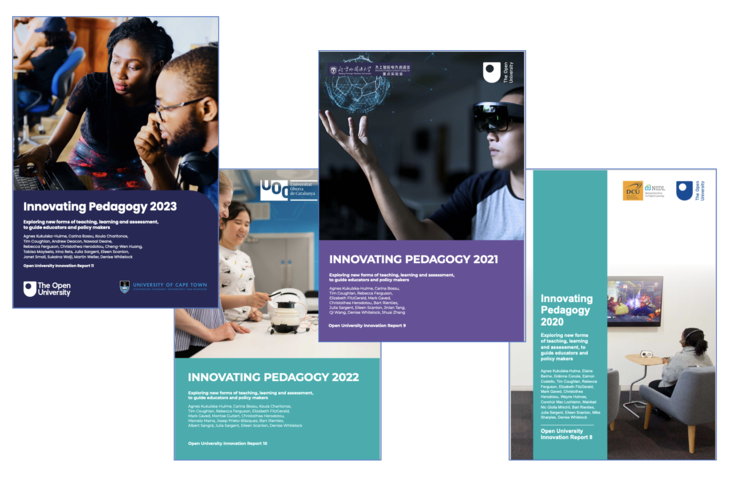

One of the ways to find out about the latest trends in pedagogy is by reading The Open University’s annual Innovating Pedagogy reports. They’re free to download and an assessment is provided for each pedagogy regarding its potential impact, and the timescale in which this is likely to be achieved.

The 2023 Innovating Pedagogy report has sections on:

- Pedagogies using AI tools: Using AI tools such as ChatGPT to support teaching and learning

- Metaverse for education: Educational opportunities through fully immersive 3D environments

- Multimodal pedagogy: Enhancing learning by diversifying communication and representation

- Seeing yourself in the curriculum: Pedagogies enabling students to see themselves in the curriculum

- Pedagogy of care in digitally mediated settings: Prioritising the wellbeing and development of students

- Podcasts as pedagogy: Embedding podcasts in teaching and learning practices

- Challenge-based learning: Rising to challenges to benefit individuals and societies

- Entrepreneurial education: Students as change agents in society

- Relational pedagogies: Working relationally in and across disciplinary and professional boundaries

- Entangled pedagogies of learning spaces: Connecting technology, pedagogy and all elements of a learning context.

What are your experiences, if any, of applying cutting-edge pedagogies in your own subject area? Do you have a favourite source of information about new teaching methods? What are your predictions for pedagogies that are likely to have a lasting impact in the next five years?

Use the discussion area to share your thoughts with your fellow learners.

© The Open University

1.13 Selecting pedagogies and technologies

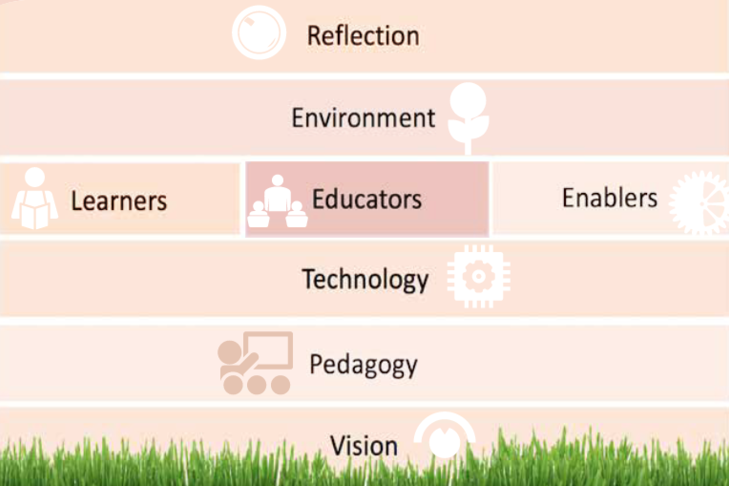

Supporting the use of pedagogy and technology © Commonwealth of Learning

Education using online tools offers opportunities for connecting learners and learning experiences, exploring the world, accessing new reference sources, personalising interactions, and sharing work outside the classroom. However, innovations that are led by technology often have little to offer learners other than the excitement of using a new tool. At the same time, as the Covid lockdowns made obvious, taking a pedagogy designed for one situtation (a classroom) and using it unchanged in a very different situation (a technology-enabled online class) often fails. Technology, pedagogy and context are entangled (Fawns, 2022) and all need to be taken into account when planning.

The image above is based on work that investigated which elements are associated with an successful innovation in technology-enhanced learning (Scanlon et al, 2013). A vision of the future provides a strong basis, followed by thoughtful consideration of both pedagogy and technology. Different groups of people, and the educational environment, can either support or obstruct change (Ferguson, 2019).

Successful online education is motivated by a vision of what is to be achieved. This might be a change in how learners feel, for example ‘In a year’s time, all our learners will be confident about presenting work to an audience’. It might be a change in how learners behave: ‘Next year, students will be aware of and use effective study techniques’. Or it might be a change in cognition: ‘All pupils in Year 5 will know what the scientific method is and be able to apply it to their own inquiries’. In each case, the vision is about learners and learning.

The next step is to put the building blocks of technology and pedagogy in place. Which approaches and tools will be most effective in achieving that vision? Even for an online educator, the tools will not necessarily be digital – sometimes paper and pencil or face-to-face discussion may be all that is needed. Multiple types of pedagogy are possible online – some examples are given in the table below.

| Learning method | Activity |

|---|---|

| Assessing | Engage in online peer review |

| Browsing | Use search engines to find resources |

| Collaborative | Work together on shared Google doc |

| Conversational | Discuss issues in a forum |

| Delivered | Listen to podcast or watch video |

| Inquiry driven | Use digital tools to collect and analyse data |

| Performative | Blog about their learning |

| Reflective | Review portfolios of activities |

Table 1. Learning methods and technology-based examples (based on work by Sharples, 2019)

A successful online experience requires engagement from different groups. At the most basic level, it’s important to make sure that both learners and educators have the skills necessary to access and use the required technology. Support staff can help by installing or upgrading hardware and software, and providing training where necessary. Managers develop policies that can support (or block) online learning initiatives, as well as approving expenditure on equipment and infrastructure. Some attention to the environment is also important, to ensure that equipment is available, updated and fully charged.

A final stage of implementation is reflection. Did the online learning experience achieve the desired effect? Is there a need to modify the experience in future, or your original vision? Were the technology and pedagogy good choices, was everybody well prepared, and was the environment set up to support learners? Pausing for thought can lead to developments and improvements, so that the initiatives that persist are the ones that have been shown to support learning.

© The Open University

1.14 Week 1 summary

You’ve now reached the end of Week 1 – this is a good point for you to stop and reflect on the topics covered so far.

The early discussion of the myth that education is ‘broken’ and technology is its disruptive saviour that was covered in the first part of Week 1 sets the tone for the rest of the course. It is a narrative that we will unpick and reassemble in each of the weeks ahead, while also considering other myths related to online education.

Looking ahead, Week 2 explores ways of making disruptive innovations both accessible and inclusive. You’ll be introduced to some strategies that should help you ensure that disabled learners are enabled to participate equally in online learning opportunities. As such, Week 2 covers a vitally important aspect of being an online educator – ensuring that innovation in education does not deny the transformative power of education to people who may already be facing other barriers to participation in society. As authors of this course, we are particularly keen that you take away the skills and awareness developed in Week 2, and are able to apply it in your own teaching.

Week 3 builds on the theme of ‘disruptive innovation’ in a different way and also extends your study of learning design. You’ll investigate strategies for evaluating the claims made about educational technologies. These strategies will help you to navigate the huge array of technology products and teaching approaches competing for your attention and can be employed within the learning design process.

Week 3 also introduces the process of evaluating your own (and others’) online teaching – an important stage of the learning design process. You’ll explore how to write effective research questions that will provide a focus for such evaluations and investigate some of the ethical considerations involved in online research.

Finally, Week 4 shifts focus from the learner to you, the educator. Prominent edtech blogger and academic Professor Martin Weller will guide you through an exploration of how educators can control and develop their online identity, and support wellbeing online. Having an online presence can allow you to contribute to the global conversation about educational innovation, allowing you to share your knowledge and experiences with others. This, in turn, can be a powerful means of shattering some of the myths you’ll encounter in this course.

In some ways being an online educator is parallel to going on an expedition (hence the photo above). It requires considerable advance planning and detailed research to choose the best tools for the job. This, in turn, will involve assessing competing claims about the quality and effectiveness of those tools. Also, it’s important to keep relevant skills up-to-date for the benefit of all involved. Hopefully, studying this course will contribute to all of these areas.

References

Conole, G (2008) New Schemes for Mapping Pedagagoies and Technologies, Adiadne Issue 56. Available at http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/56/conole/ (Accessed 13 December 2023)

Cooper, A. (1999) The Inmates are Running the Asylum - Why High-Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity, SAMS publishing.

Educateuse. (2025). Our Mission. Available at https://www.educause.edu/about/mission-and-organization (Accessed 06 February 2025).

Farrow, R. (2015) ‘Open education and critical pedagogy’, Learning, Media and Technology, vol. 42, no. 2 [online]. Available at https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1113991

Fawns, T. (2022) ‘An entangled pedagogy: Looking beyond the pedagogy - technology dichotomy’, Postdigital Science and Education, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 711-728.

Ferguson, R. (2019) Pedagogical Innovations for Technology-Enabled Learning. Commonwealth of Learning, Burnaby, Canada.

Kukulska-Hulme, A., Bossu, C., Charitonos, K., Coughlan, T., Deacon, A., Deane, N., Ferguson, R., Herodotou, C., Huang, C-W., Mayisela, T., Rets, I., Sargent, J., Scanlon, E., Small, J., Walji, S., Weller, M., & Whitelock, D. (2023). Innovating Pedagogy 2023: Open University Innovation Report 11. Milton Keynes: The Open University. https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/innovating/ (Accessed: 22/01/2025)

Hansard (2023) Grand Committee: Educational Technology 23 November 4pm [online]. Available at https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2023-11-23/debates/507ffa6e-c43d-45bc-aa0e-77d9197c6068/GrandCommittee (Accessed 13 December 2023)

Marshall, C. (2011) Whatever happened to Second Life? Available at https://www.techradar.com/news/internet/whatever-happened-to-second-life-1030314

Scanlon, E., Sharples, M., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Fleck, J., Cooban, C. and Ferguson, R. (2013) Beyond Prototypes. TEL Research Programme, London.

Sharples, M. (2019) Practical Pedagogy: 40 New Ways To Teach and Learn. London: Routledge.

Mor, Y. and Craft, B. (2012) ‘Learning design: reflections on a snapshot of the current landscape’, Research in Learning Technology, vol. 20. DOI: 10.3402/rlt.v20i0.19196

Acknowledgments

Myths, hype and reality in online education Case study: Second Life

Applying accessibility guidelines to online teaching Introduction to accessibility guidelines

PhotoDisc/Getty Images

Linden Labs

Courtesy of Tate Digital © Tate, London, 2018

Copyright © [2015] World Wide Web Consortium, (MIT, ERCIM, Keio, Beihang). https://www.w3.org/copyright/document-license-2015/

Developing a Research Question

Laurier Library This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Myths, hype and reality in online education: The students of the future

Educause, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Online research ethics Ethics and the ‘murky’ public/private distinction online

Second Life © Linden Research, Inc. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Who am I online? Visitors & Residents video

Visitors and Residents by jiscnetskills, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

1.15 Assess your understanding of Week 1

This quiz is designed to assess your understanding of some of the topics covered in Week 1. You have unlimited attempts to complete it.

Quiz rules

- Quizzes do not count towards your course score, they are just to help you learn

- You may take as many attempts as you wish to answer each question

- To receive a statement of participation at the end of this course, you must achieve a minimum score of 40 on this quiz.

- You can skip questions and come back to them later if you wish