1 How do antibiotics work?

1.1 Selective toxicity

Drugs should demonstrate ‘selective toxicity’; that is, they target the disease-causing organism while causing no or minimal harm to the patient. This principle, proposed by Paul Erlich in 1900, is still firmly entrenched in medical and veterinary research and practice today (Valent et al., 2016).

Underpinning selective toxicity are the differences between bacterial pathogens and human or animal cells. It is these differences that antibiotics (and other drugs) exploit to exert their specific effects.

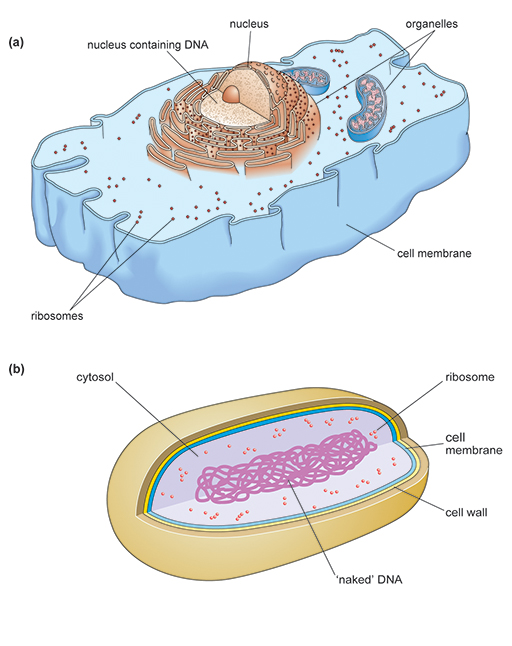

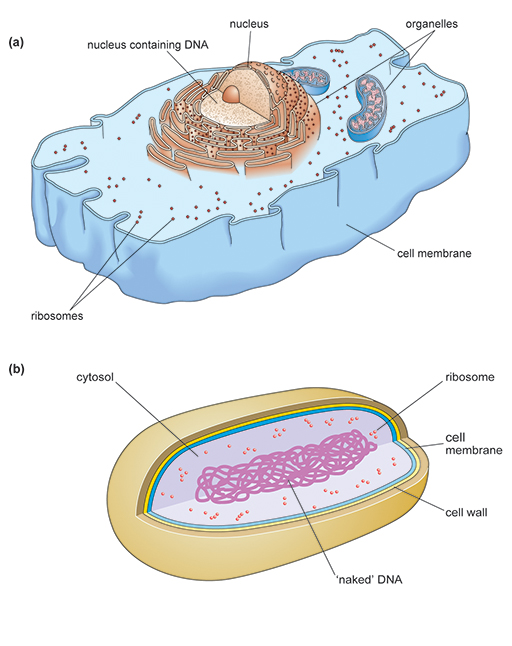

There are two distinct types of cell. Bacteria are prokaryotes while human and animal cells are eukaryotes. Figure 1 below shows the basic structures of each type of cell.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of a typical (a) eukaryotic animal cell and (b) prokaryotic bacterial cell (not drawn to scale).

Show description|Hide descriptionPart (a) is a simplified 3D diagram of a eukaryotic animal cell. The cell is bounded by a thin, flexible cell membrane. Inside is the nucleus, which is also membrane-bound and contains the DNA. Also present are membrane-bound components called organelles, and many tiny structures called ribosomes. The fluid interior of the cell is called the cytosol. The ribosomes are either free in the cytosol or attached to the outside of membranous sacs. Part (b) is a simplified 3D diagram of a prokaryotic bacterial cell. A thick cell wall surrounds the cell membrane. There is no nucleus nor are there any interior membranes; the ‘naked’ DNA and all the ribosomes are free in the cytosol.

Although there are similarities between the two cell types, eukaryotic cells are structurally much more complex. Prokaryotes and eukaryotes carry out the same essential processes necessary for survival, such as making new proteins, metabolism and reproduction, but these processes are not identical. For example, different proteins might be produced or different enzymes used to drive key chemical reactions.

Antibiotics are selectively toxic because they target structural features or cellular processes in the bacterial pathogen that are different or lacking in the host’s cells.