Unit 4: Report and respond

| Site: | OpenLearn Create |

| Course: | Implementing Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector |

| Book: | Unit 4: Report and respond |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 25 November 2025, 3:11 PM |

Table of contents

- Introduction

- 4.1 What is the difference between SEAH and SGBV?

- 4.2 Barriers to reporting

- 4.3 Disclosure & reporting

- 4.4 Whistleblowing and a ‘survivor-centred approach’

- 4.5 Adopting a ‘survivor-centred approach’

- 4.6 Duty of care and the importance of safeguarding staff

- 4.7 Unit 4 Knowledge check

- 4.8 Review of Unit 4

Introduction

In Unit 3 you developed your understanding of power and how the misuse of power can cause harm and be hugely detrimental to someone’s physical, emotional and sexual wellbeing.

You then refreshed your understanding of how to undertake risk assessments and what safeguarding measures to put in place to mitigate against this harm. We also looked at this in the context of implementing safeguarding in the programmes that are working with people with disabilities.

In this unit we explore how to implement reporting and responding to safeguarding measures when working on programmes with a focus on sexual and gender-based violence. We look at how beliefs about gender can operate as barriers, preventing people from reporting SEAH and accessing support for safeguarding concerns. We also identify barriers to reporting, share how to create accessible and responsive reporting mechanisms, and ensure support services are accessible.

4.1 What is the difference between SEAH and SGBV?

Are you clear about the different terminology?

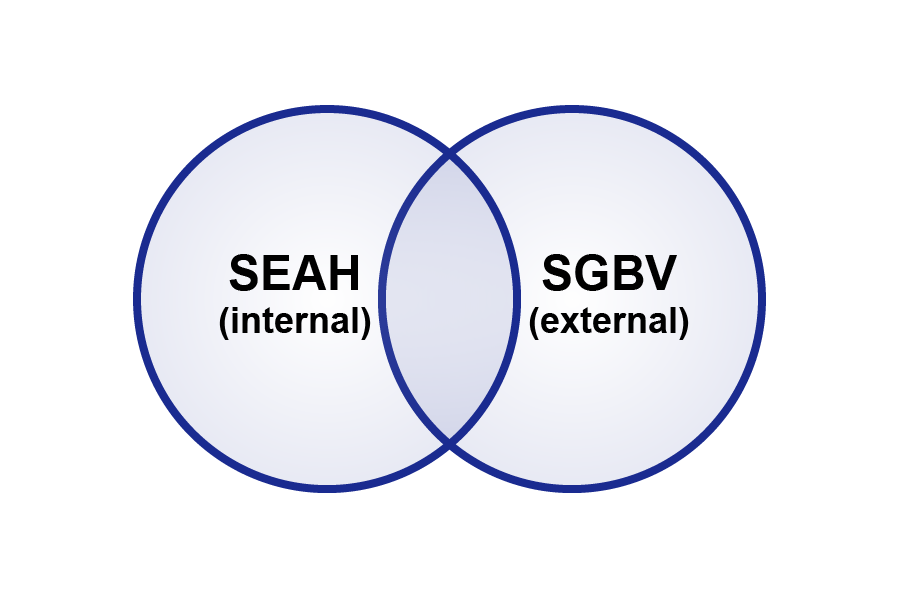

Sexual Exploitation, Abuse and Harassment (known as SEAH) is sexual misconduct committed by staff in your organisation and associated personnel (i.e., volunteers, board members, partners, advisors, etc.) against others (such as fellow staff, associated personnel, volunteers, beneficiaries and communities).

Sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment is known as SEAH. Protecting people from SEAH is an organisational duty of care to staff and associated personnel inside an organisation through policies, procedures and practices based on international safeguarding standards, donor requirements and national laws. It is not a ‘programme’ in the strict sense of the word, even though it does require resources, personnel and leadership commitment.

Sexual and Gender-based violence (SGBV) is harm perpetrated by individuals external to the organisation. Obviously, there can be a cross-over as shown in the diagram above. However, the concerns when reported may be dealt with differently as it depends on the context.

SEAH and SGBV concerns all come under the wider umbrella of ‘safeguarding’, which is about protecting people from all forms of sexual harm, including men and women, boys and girls. However, the implementation of safeguarding measures may be affected by the gender roles that men and boys and women and girls are perceived to possess in the society in which we work, as well as the assumptions and biases (conscious and unconscious) that we may have as aid workers. Assigning gender roles to women and girls, men and boys may be barriers to reporting SEAH.

To learn more about SEAN and SGBV, follow the links below:

4.2 Barriers to reporting

© Serhii Radachynskyi / 123RF

In Course 1: Introduction to Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector we explored barriers to reporting and how societal perceptions, myths and assumptions, and stigma and shame play a big part in preventing survivors of SEAH from reporting.

It is not uncommon for survivors to be blamed for suffering harm from SEAH.

For example, they may be accused of not taking appropriate precautions, exposing themselves to danger, or dressing in ways that encourages or invites SEAH. Where victim-blaming is prevalent, people may be more reluctant to report. Survivors may also internalise blame and feel that they do not deserve help or support.

© Ponomariova_Maria / iStock / Getty Images Plus

There are also negative consequences of reporting. Sometimes survivors may not want to report for fear that they would not be believed, particularly if the perpetrator is in a more powerful position or enjoys the support of leadership/management.

They may also worry that reporting may result in aid to their community being stopped, or that reporting will damage their chances of getting married in the future. The fear that the perpetrator would lose their job leading to impoverishment of their family may also deter reporting.

Other factors inhibiting reporting include fear of retaliation (by the perpetrator, families, employers or society) and limited trust in internal or external reporting systems.

|

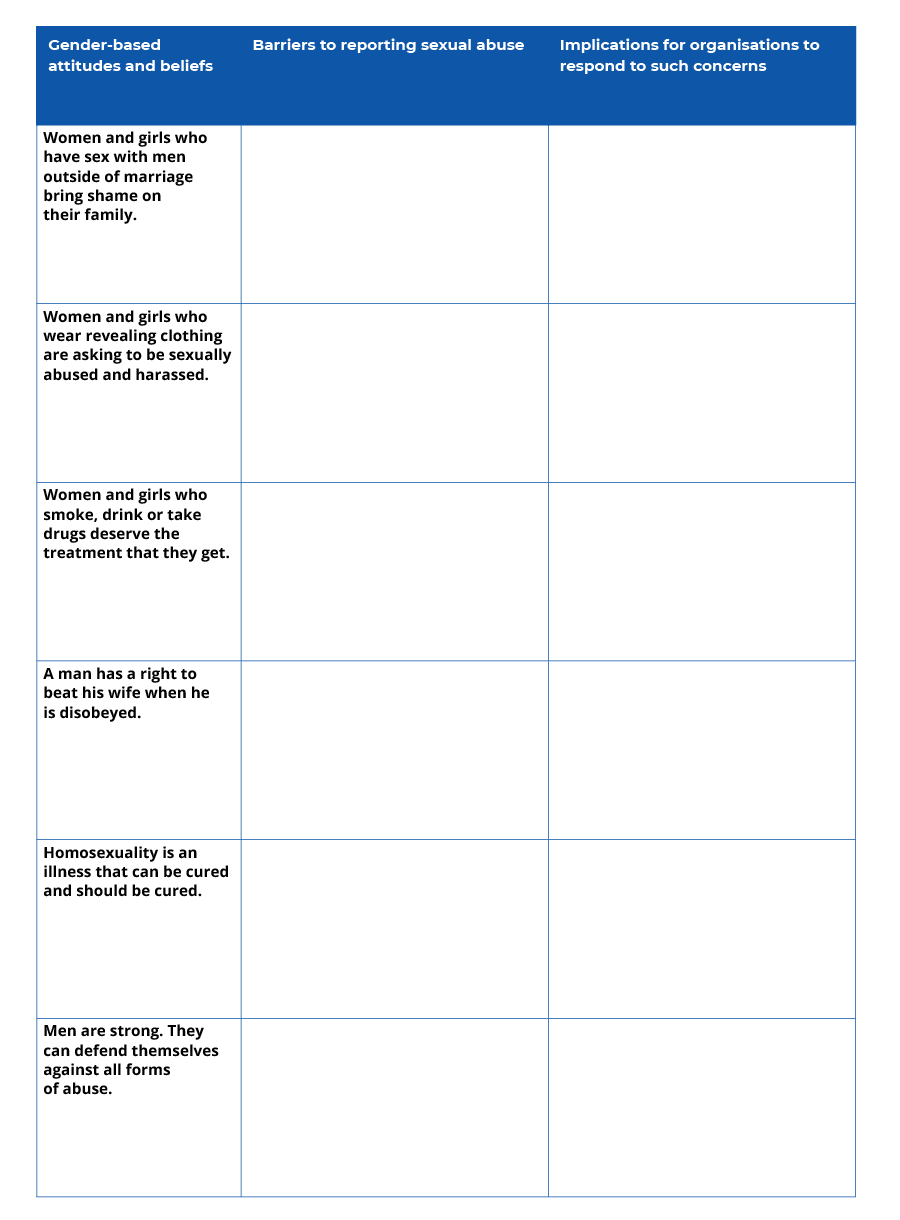

Activity 4.1 Discriminatory attitudes and beliefs Here we explore some of the barriers to reporting which naturally impact on the effectiveness of implementing organisational safeguarding measures. The table below shows a list of discriminatory gender attitudes and beliefs that it is not uncommon to encounter in different parts of the world. What do you think the implications of these beliefs might be for reporting safeguarding concerns in the context of organisational work or programming? Use the table below on discriminatory gender attitudes and beliefs and fill in the two missing columns. Here is a writable version of the template shown below. You can type into this PDF form and then save it and/or print it.

Here is a version of the template with some ideas in each of the columns to compare with your own. |

Barriers to reporting for men and boys

© stock_colors / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Whilst it is important to provide support and services, such as safe spaces, counselling services and medical care, specifically for women and children, it is equally important to make sure men, boys and people of non-binary genders (LBGTQI – lesbian, bisexual, gay, transgender, queer (or questioning) and intersex) are not overlooked and that their specific needs are catered for.

Disclosure of SEAH by men and boys may be perceived by society as a sign of weakness. They may fear shame, ridicule, further harm or not being believed and avoid reporting it.

|

Activity 4.2 Men, boys and sexual violence Read this article from the Refugee Law Project (2020) in Uganda, about an NGO that works with men and boys affected by sexual violence. It outlines some of the barriers to reporting and the experience of working with male survivors. In your learning journal reflect on some of the ways organisations could support men and boys to disclose safely and how they might respond. |

Barriers to reporting for LBGTQI people

© ljubaphoto / iStock / Getty Images Plus

In many contexts, heterosexual relationships are considered the norm, with other kinds of relationship considered something ‘deviant’ or ‘unnatural’ to be treated or cured.

These kinds of views might not only deter survivors of same-sex abuse from reporting concerns, but also influence ideas about what kind of ‘support’ is available or appropriate.

Due to phobias and stigmas associated with being non-heterosexual, LGBTQI survivors of sexual violence face specific challenges when attempting to access support services.

Barriers faced by LGBTQI people in accessing help or support can be complex and include:

- Structural: Protection services for LGBTQI people are non-existent because their sexuality is illegal in many countries.

- Cultural: Services which may be available are not designed or delivered to be accessible to or inclusive of LGBTQI people.

- Individual: LGBTQI people’s perception of the support system, of their selves, of the abuse, and of their relationship with the perpetrator/s.

|

Activity 4.3 Sayed – A case Study Read this case study about Sayed, who is an expatriate staff member working for an international agency. Sayed is an expatriate staff member working for an international agency in Country X. This international agency works on SGBV programming focused on supporting women and girls. Sayed has a relationship with Jack, a male colleague from another organisation. Initially the relationship was very pleasant, however Jack started getting jealous, controlling and abusive. Jack threatens to inform Sayed’s family about his sexuality and Sayed fears deportation back to his home country where those like him will be imprisoned and probably tortured. Sayed contacts a local domestic violence service, which refuses to offer him support saying they don’t provide support to male victims. One evening Sayed could not stand it any longer: he calls Jack’s employer to complain following a physical attack by Jack. The employer feels very uncomfortable with this disclosure and does not want to intervene. The employer warns Sayed that he should not make up stories and waste organisational time. (© Adapted from Barriers faced by LGBT+ people in accessing non-LGBT+ domestic abuse support services) Having read the short case study, consider these two questions noting your responses in your learning journal:

|

4.3 Disclosure & reporting

How disclosures are handled is crucially important if safeguarding reporting is to be effective. This section is an opportunity to explore and discuss good practice.

Managing disclosure from adult survivors

![]()

Watch the video above, which is about managing disclosure of abuse from vulnerable adults.

The table below gives some top tips when managing disclosure from SEAH adult survivors, ensuring a survivor-centred approach.

Do remember that any sharing of information to other people should be done on a need-to-know basis and as far as possible with the informed consent of the survivor.

Here is a PDF version of the table above.

To learn more about managing gender-based violence, follow the link below:

Mandatory reporting

© infografx / 123RF

You will remember that the UNSG Bulletin on SEA and the IASC PSEA 6 Core Principles make it mandatory for staff and personnel to promote the code of conduct and to report SEAH ‘through established reporting mechanisms’ whether their concerns relate to the behaviour of staff from their own agency or from another.

Here are a few suggestions on what mechanisms should be in place to help make mandatory reporting effective:

- Staff need to be informed when to report, to whom to report to and how. It is good practice that safeguarding concerns should be reported directly to the organisational in-country or programme-level Safeguarding Focal Points and/or Safeguarding Leads and/or a Designated Safeguarding Board Member, all of whom should be trained and skilled to manage reports that come in.

- Internal reporting mechanisms must be safe, confidential and accessible.

- Reporting must be done in a timely manner, since any delay could result in greater harm.

- Organisations should take a survivor-centred approach when managing reports.

- Even anonymous reports should be taken seriously, and initial inquiries made.

Following donor commitment and grantee requirements emanating from the Safeguarding Summit held in London in 2018, international organisations have also included a ‘zero tolerance towards SEAH’ commitment in their policies and procedures.

This means that organisations will challenge inappropriate behaviour when it occurs and will take appropriate and timely action when concerns are brought to their attention. It also means continually improving processes and practices to keep staff, volunteers and beneficiaries safe from harm.

|

Does your organisation have a mandatory reporting and/or zero tolerance policy? Do you think it has had any impact? |

Reporting SEAH to authorities

In some countries it is mandatory for professionals, such as doctors and teachers, to disclose serious safeguarding concerns to authorities about children who may be affected. Such authorities may include law enforcement or social services (where they exist).

The rules relating to mandatory reporting regarding adults may be more relaxed, unless they are classified as ‘vulnerable adults’. Professionals must report or face criminal sanctions, such as fines and/or imprisonment.

However, in some countries, mandatory reporting is hugely detrimental to survivors of SEAH, since they could be criminally prosecuted themselves. For example, in jurisdictions where a female is found to be alone with a man who is not her father or husband, this can amount to a criminal act, even if that female was coerced or forced into that position.

In many contexts, authorities may not be equipped to question survivors or victims in a sensitive way or think about survivor-centred approaches. Sometimes they may be corrupt, disinterested or biased towards the perpetrator because of myths and assumptions about female or male survivors in that society.

Therefore, it is very important to assess the risk of reporting to authorities and ensure that survivors are not re-traumatised or even criminally prosecuted for harm they have already suffered.

|

Activity 4.4 Reporting SEAH - poll Reflect on the three following questions and respond using the poll (all responses are anonymous). Reporting SEAH to authoritiesDo authorities handle SEAH reports well?Do authorities support survivors of SEAH well? |

4.4 Whistleblowing and a ‘survivor-centred approach’

Whistleblowers are an important source of reporting, and this section will consider how agencies should ensure they are protected. Once we have received a report it is important that our responses are survivor centred.

The whistleblower

© danijelala / Getty Images

It is often the case that those who report safeguarding concerns are not survivors or victims, but ‘whistleblowers’.

A whistleblower is a person, usually an employee, who discloses information or activity within an organisation that they believe to be illegal, illicit, unsafe, or an abuse of power or resources.

Whistleblowers can choose to disclose information or make allegations either internally or externally to the organisation. Indeed, the reason that safeguarding has risen high on the international aid sector’s agenda is largely due to whistleblowers who exposed sexual exploitation, abuse and sexual harassment within international organisations that they used to work for.

You have already seen how there may be a number of things that might inhibit people from reporting safeguarding concerns. For example, they may be afraid of stigma or reprisals. They might assume that they won’t be believed or that action will not be taken, or that reporting might make the problem worse.

It is important to identify and understand the barriers that might prevent whistleblowers from reporting safeguarding concerns and think about how your organisation might better enable them. It is important to make sure that whistleblowers know that they will be supported and protected.

Protecting the whistleblower

When thinking about your organisation and how it can support and protect whistleblowers, the following points are important:

- Your organisation must have a whistleblowing policy in place which guarantees that whistleblowers will be supported and protected and that they are clear about how their complaint will be handled.

- Whistleblowers have a right to anonymity if requested and to receive feedback on their complaint at an appropriate point.

- Mandatory training on whistleblowing should be provided to all staff, especially for new staff, volunteers, and consultants when they join an organisation, ideally as part of the induction process.

- Reporting procedures should be known and accessible to all staff. People should be informed of their right to be safeguarded from harm and made aware of how to report safeguarding concerns and to who.

- Staff must be confident that the system will protect and support them. Consultation with staff on reporting procedures is important here. When done effectively, consultation can help build confidence in the safeguarding process and enable reporting.

- Your organisation must demonstrate that it is willing and able to take swift and appropriate action.

- Whistleblowers must be confident that their concerns will be handled confidentiality and that they will be protected from reprisals or any harm.

|

Activity 4.5 Checklist on whistleblower protection You might find the template below useful for exploring your organisation’s whistleblowing policies and procedures. Once you have identified any areas for improvement think about how you might effectively address them. You may need to discuss this with others in your organisation.

|

For further reading please visit: Whistleblower protection guidance | Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub (safeguardingsupporthub.org)

4.5 Adopting a ‘survivor-centred approach’

© Christian Horz / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Mandatory reporting does have its challenges.

For example, how should aid workers balance their duty to report to a Safeguarding Lead if the survivor refuses? Or how does the organisation investigate a safeguarding concern under its ‘zero tolerance’ policy if the survivor wants to stay anonymous? Or if the misconduct committed is a criminal act, such as rape, and the organisation has a legal duty to report the matter to law enforcement, but the survivor refuses?

A ‘survivor-centred approach’ means the rights, needs and wishes of the survivor (or victims) are prioritised. For example, the survivor has a right to:

- Be treated with dignity and respect instead of being exposed to victim-blaming attitudes.

- Choose the course of action in dealing with the violence instead of feeling powerless.

- Privacy and confidentiality instead of exposure.

- Non-discrimination instead of discrimination based on gender, age, race/ethnicity, ability, sexual orientation, HIV status or any other characteristic.

- Receive comprehensive information to help them make their own decision instead of being told what to do.

Note: A “survivor-centred approach” is not a “survivor-led approach”. The organisational duty of care goes beyond the survivor as organisations must take into consideration the risk of the Subject of Concern committing misconduct again if they continue to stay employed or associated with the organisation.

This approach helps to promote the survivor’s recovery and their ability to identify and express their needs and wishes, as well as to reinforce their capacity to make decisions about possible interventions (UNICEF, 2010). Organisations must have the resources and tools they need to ensure that such an approach is implemented (Source: UN Women, Survivor-centred approach).

When implementing safeguarding measures, we should ask ourselves this question: ‘Will this action be in the best interest of the survivor and other potential survivors or victims?’ Therefore, it is important for organisations to carry out a risk assessment when discharging their duty of care when safeguarding known survivors, as well as other potential victims, from being harmed. Organisations should carry out an impartial investigation into the alleged misconduct to address the misconduct and eliminate any further risk.

|

Activity 4.6 Applying a survivor-centred approach What is your understanding of a survivor-centred approach? How would you exercise this approach if the survivor was a child or a person with disability? |

|

Activity 4.7 A SEAH scenario Apply what you have learnt so far to the SEAH scenario below. How would you as the Safeguarding Lead react in this situation? Make some notes in your learning journal. You are the Safeguarding Lead for your organisation. You are informed that Tasmin was seriously sexually harassed by another member of staff who has since gone on long-term leave. Tasmin wishes to go to the police so that justice will be served. The Country Director, however, informs you that in this country there is a high risk that the alleged perpetrator will be violently attacked and even killed while in custody, as suspected sex offenders are known to be assaulted by police and other inmates in prison. (© Adapted from Global Interagency Security Forum, Scenarios for Senior Leadership) |

Balancing the duty of care

![]()

Hasan, a Human Resources Manager based in Amman, has a question about balancing the duty of care.

Watch the video above to learn more about Hasan’s question and the response he is given.

Mapping of referral services

© Rawpixelimages / Dreamstime.com

Part of a survivor-centred approach is to provide survivors with information that is supportive and easily understood so that they can make informed decisions.

Organisations should map services to manage how they could respond to safeguarding concerns. It is worth being particularly attentive to medical services who provide sexual, reproductive health and psychosocial support services, and to women’s groups who provide safe spaces and/or refuges.

You will also need to consider whether these services have trained personnel to support survivors who are referred to them. Are they accessible for people with disabilities, and might any fees be incurred? This analysis will help you think about who is and who is not able to access each service. You should also consider how local ideas and beliefs about gender might influence access.

|

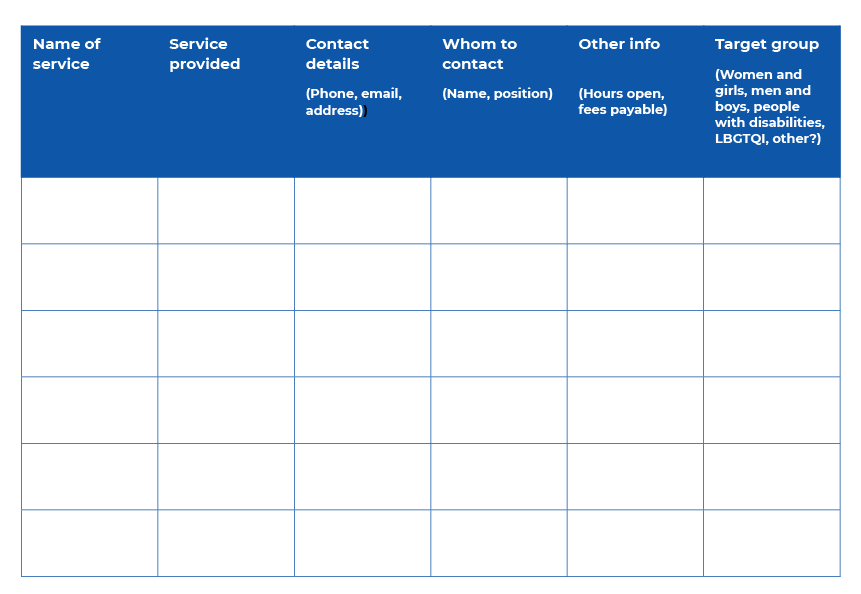

Activity 4.8 Mapping of referral services Use the table below to map out support services available to survivors of SEAH in the area you or your organisation work. Consider each service and the potential barriers there might be to accessing these services for different kinds of people. Include not just services provided by your own organisation, but also those provided by others operating in the same area. Remember that it is really important that this list of referral services is updated regularly and is easy for the staff and the people you serve to access quickly. Here is a writable version of the blank template shown below. You can type into this PDF form and then save it and/or print it. Expand it to list as many services as you are aware of – you could check with colleagues if there are any services other than those you have identified. As you undertake the activity think about what the challenges might be to accessing services and how they might be overcome.

(© Adapted from IASC PSEA Mapping Tool for GBV services) |

Mapping legal requirements

It is equally important to ensure you are aware of the legal requirements in the environment in which you work.

After all, ignorance of the law is not a valid defence, and part of exercising our duty of care is ensuring that staff and programmes are up to date on the key legal requirements.

Are you confident in the answers to the following questions? If not, then explore with your colleagues what the legal situation is:

- What are the legal definitions and understanding of sexual assault or rape in the country you work in?

- How does a survivor file a complaint and where can this be made?

- Is there a time limit for sexual assault crimes to be reported?

- Are there trained legal and other professionals to deal with sexual assault/rape?

- Does the law protect the identity and dignity of the survivor?

- Could a prosecution go ahead even when the survivor withdraws from the process?

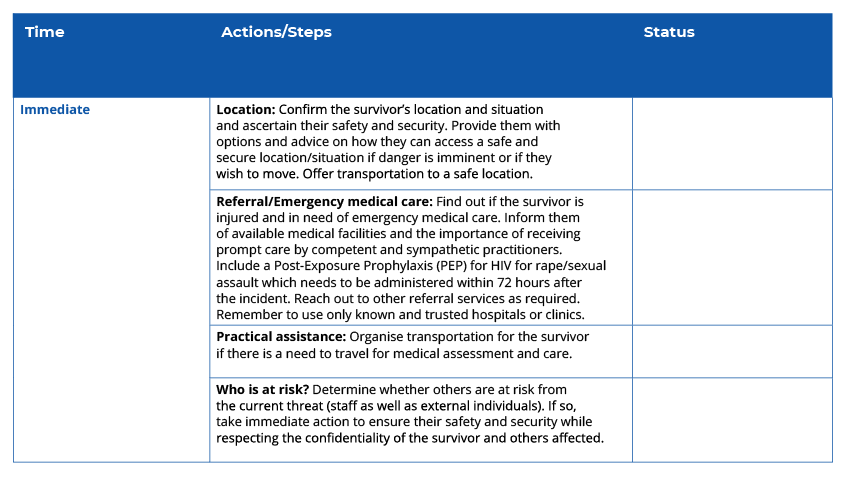

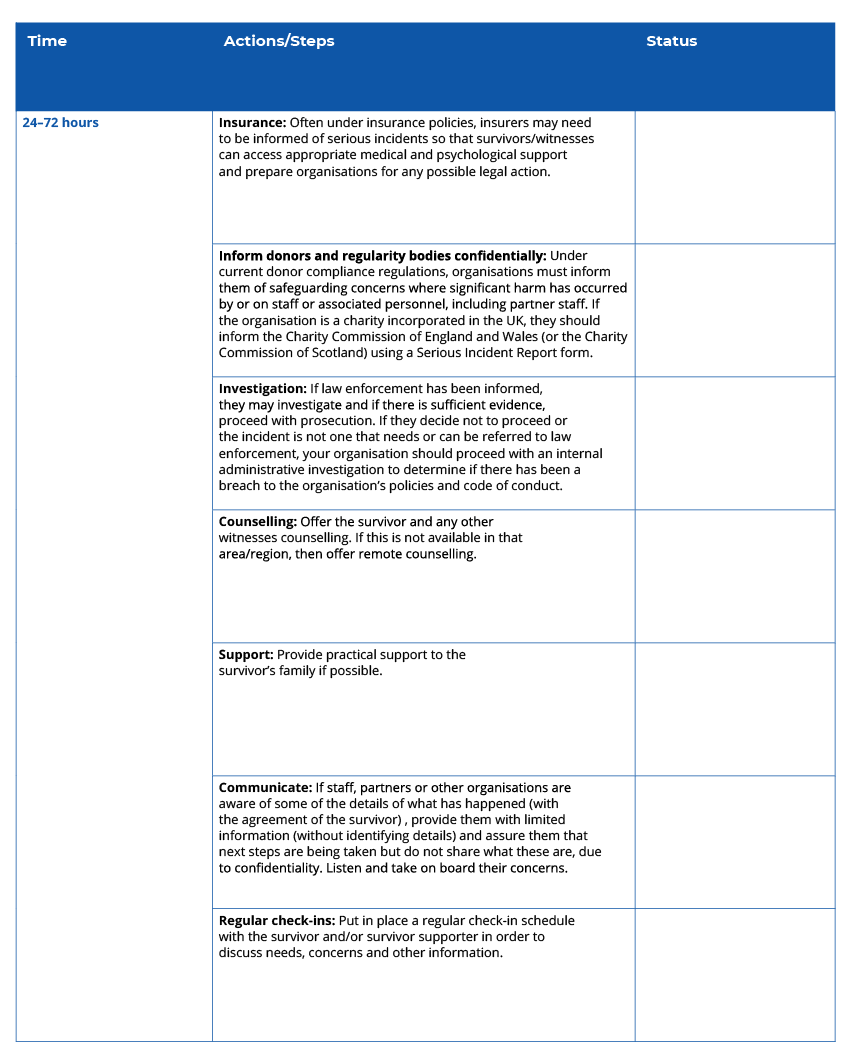

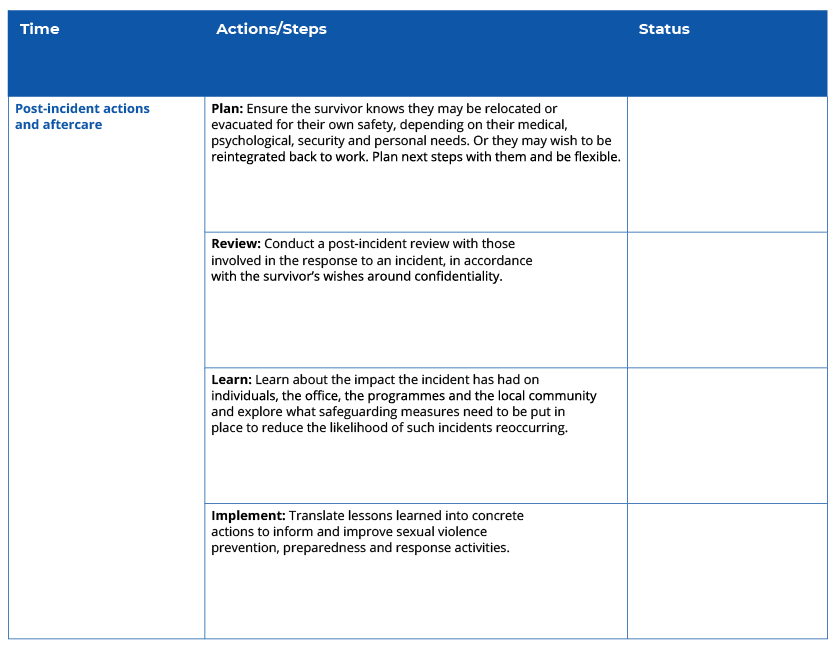

Response checklist

© baona / iStock / Getty Images Plus

It may be helpful to have a response checklist to support you in your role if you are the Safeguarding Lead or Focal Point and you have to manage safeguarding concerns which are reported to you.

Below are examples of a response checklist – split into four time periods. Remember you will need to obtain the survivor’s informed consent before taking some of the steps mentioned.

Here is a writable version of the response checklist. You can type into this PDF form and then save it and/or print it.

(© Adapted from GISF’s Sexual Violence Response Checklist (Tool 4))

4.6 Duty of care and the importance of safeguarding staff

© natasaadzic / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Organisations have a duty of care to prevent and respond to incidents of safeguarding concerns, including SEAH, against their staff.

Sexual or other forms of misconduct on staff and organisational representatives in the course of their work is a growing concern for organisations, and they need to be prepared for disclosures and how to manage them. If not managed well, disclosures of safeguarding concerns can be hugely distressing to survivors and create long-term problems for them.

When exercising an organisational duty of care, organisations should think about the following:

- Are there prevention measures, policies, and procedures in place to address different forms of safeguarding concerns?

- Are staff members in various roles appropriately trained? Are those expected to interact with survivors comfortable doing so?

- Does the organisational culture support staff in reporting incidents of sexual violence?

- Is the organisation conducting transparent, professional, and impartial investigative or inquiry processes?

- Do staff members at all levels of the organisation understand their rights and obligations to the creation and maintenance of a safe and healthy workplace and living environment (often known as a ‘safeguarding culture’)?

These questions are taken from Duty of Care: Protection of Humanitarian Aid Workers from Sexual Violence. If you want to learn more about duty of care download and read the rest of this report.

Example of good practice

The Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance (WHPCA) is a membership organisation based in the UK with 350 members in 100 countries. It supports organisations such as BSMMU in Dhaka in Bangladesh, which provides palliative care to older and disabled clients in their homes.

Providing palliative care in a client’s home is a relatively new concept in Bangladesh, and it is becoming increasingly popular with young women, who view this as a noble profession, as it falls in line with their cultural values of respecting and caring for older people.

![]()

Watch the video above, in which Lailatul, the head nurse at a medical hospital in Dhaka, explains the importance of safeguarding her staff (the palliative care assistants) by implementing the ‘two-adult rule’ when they travel long distances and/or work alone.

![]()

To learn more, you can follow up with these readings:

4.7 Unit 4 Knowledge check

The end-of-unit knowledge check is a great way to check your understanding of what you have learnt.

There are five questions, and you can have up to 3 attempts at each question depending on the question type. The quizzes at the end of each unit count towards achieving your Digital Badge for the course. You must score at least 80% in each quiz to achieve the Statement of Participation and Digital Badge.

4.8 Review of Unit 4

© Feodora Chiosea / iStock / Getty Images Plus

In this unit we have looked at the links between safeguarding against SEAH and SGBV.

We focused on the importance of thinking through how to report on and respond to safeguarding concerns when they are reported by different survivors – whether they are women and girls, men and boys, or people who are LBGTQI.

We discussed the various barriers to reporting for each of the different categories of survivors, the importance of understanding the national legal context, and how we can support individuals to disclose SEAH concerns.

We also discussed a survivor-centred approach from a gendered perspective and how to map available services and support survivors to access these services within the local context.

Finally, we looked at how organisations should also exercise their duty of care to safeguard their own staff and associated personnel from SEAH.

|

Learning journal Before you move on to Unit 5, reflect on your own learning so far. Consider the following questions and respond to the questions in your learning journal:

|

Now go to Unit 5: Improving accountability in safeguarding.

References

Connell, R. W. (1995) Masculinities, Los Angeles, University of California Press.

Dolan, C. (2002) ‘Collapsing masculinities and weak states – a case study of northern Uganda’ in Cleaver, F. (ed.), Masculinities matter! Men, gender and development, London, Zed Books.

Feder, G. and Howarth, E. (2014) ‘The epidemiology of gender-based violence’, ABC of domestic and sexual violence, Chichester, John Wiley.

Global Interagency Security Forum (2017) Duty of Care: Protection of Humanitarian Aid Workers from Sexual Violence, Online. Available at GISF (Accessed 8 September 2021).

Gough, B., Robertson, S., and Robinson, M. (2016) ‘Men, ‘masculinity’ and mental health: critical reflections’, Handbook on Gender and Health, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing. Also available online at Edgar online (Accessed 07 June 2021).

RLP (2020) The Loud Silence: The plight of refugee male survivors of conflict-related sexual violence, Online. Available at onendavid.com (Accessed 7 September 2021).

UN WOMEN (n.d.) Ending violence against women, Online. Available at UN Women(Accessed 8 September 2021).