Resource 2: Asking questions about feelings

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

You need to be sensitive when asking questions about feelings. Children might not always want to talk about their feelings in public. You need to ask the kinds of questions that allow children to give answers they feel comfortable with.

One way to do this is to ask questions to the whole class instead of to individuals. Ask questions such as: ‘Who likes …’ and ‘Who doesn’t like …’ with pupils putting up their hands. If they see that they are part of a group, the children will feel less embarrassed about revealing their feelings.

You can do the same by brainstorming different questions. For example, ask: ‘What makes you scared?’ and then write all the pupils’ ideas down on the board very quickly. This way, you won’t make the individuals feel too exposed.

If you want them to talk more intimately about their feelings, organise them into pairs and groups to do similar exercises. They will probably find it easier to speak in a small group.

You can also use stories to explore sensitive ideas – this helps pupils to talk more freely as they do not feel they are talking about their own experiences.

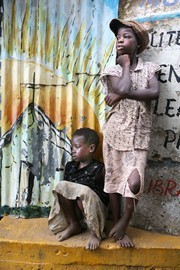

You can make up your own stories to share with your pupils. Or you could use the story of Kenyan street children below to stimulate discussion. Either copy the sheet – one for each group – or read from your copy to the whole class.

After they have heard the story taken from World Street Children News, ask them how they feel about the children’s lives. Are they similar or different to their own lives? How would they feel about living like that? What would they like and dislike about this kind of life?

World Street Children News: Kenya Streetkid news

Adapted from: BBC World, Website

Adapted from: Irin News, Website

There are 250,000–300,000 children living and working on the street across the country with more than 60,000 of them in Nairobi. Shanty towns like Kibera and Korogocho are home for some of these children.

‘I lost my parents three years ago and since then I have been living in the streets without shelter and assurance of having food every day. Nobody cares about me; whether I live or not,’ said William Githira, 15, who lives in the streets of the Kenyan capital. ‘People don’t want to look at me. I’m trash. I don’t want to live in the streets, but I have nobody. My uncle beat me hard when I lived there, and so I ran. Living in the street is the only way to survive,’ he added.

In the past decade, the number of street children has increased in many African countries due to deepening poverty. The situation described by William is not uncommon in big cities like Nairobi and elsewhere in the developing world.

As half of the total population of Kenya is under 18, the living conditions of street children are one of the greatest challenges facing the government of President Mwai Kibaki. Experts estimate that there are 250,000–300,000 children living and working on the streets, with more than 60,000 of them in Nairobi. Kisumu, on Lake Victoria, and Mombasa, on the coast, also have large populations of street children.

Street children face endless cruelties. Their rights have been violated many times by the adults who were supposed to protect them.

In many cases, these children are subject to sexual exploitation in return for food or clothes. Often, police detain and beat them without reason.

‘Kenya is a mess! The conditions for street children are terrible,’ said Miriam Ndegwa, programme associate of Youth Alive Kenya.

Geoffrey, 23, described his experience in a police station: ‘I was sleeping one night in the street when the police came and took me to the police station. I did nothing wrong. In the police station I was beaten to confess a crime I did not do. [The police officer] wouldn’t stop until I agreed to what he said. He beat me everywhere with his cane.’

The scavengers or ‘chokora’

Nairobi’s street children are easily recognised with their trademark sacks slung over their backs, searching through dustbins. They are branded ‘chokora’ or scavengers.

In order to survive on the streets, young people often beg, carry luggage, or clean business premises and vehicles. Others earn some money by collecting waste paper, bottles and metals for recycling.

The children sometimes assist the city council cleaners in sweeping and collecting garbage.

Eddy Omondy, a 15-year-old orphan who has been living in the streets for four years, told IRIN that he used to collect garbage, and help load and unload market goods, earning him up to 80 KSH (US $1) a day.

Some earn their money in less honest ways; pick-pocketing or violent robbery.

Adapted from: Street Kids News, Website

Resource 1: Similarities and differences