Resource 4: Child labour in Africa

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

What is child labour?

Child labour: all forms of work by children under the age laid down in the International Labour Organisation (ILO) standards (normally 15 years or the age of completion of compulsory schooling subject to some exceptions).

Worst forms of child labour: slavery, debt bondage, prostitution, pornography, forced recruitment of children for use in armed conflict, use of children in drug trafficking and other illicit activities, and all other work likely to be harmful or hazardous to the health, safety or morals of girls and boys under 18 years of age.

What is the situation of child labourers?

The ILO has recently estimated that some 246 million children aged 5–17 years are engaged in child labour around the world. Of these, some 179 million are caught in the worst forms of child labour.

Roughly 2.5 million children are economically active in the developed economies, 2.4 million in the transition countries, 127.3 million in Asia and the Pacific, 17.4 million in Latin America and the Caribbean, 48 million in Sub-Saharan Africa and 13.4 million in the Middle East and North Africa.

Workers under 18 face particular hazards. For example, in the US, the rate of injury per hour worked appears to be nearly twice as high for children and adolescents as adults.

Similarly, a survey of 13 to 17 year olds in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden in 1998–99 revealed injury rates ranging from 3 to 19% of children working before or after school. In the developing countries, an ILO study found average rates of injury and illness per 100 children ranging from a low of 12% in agriculture (for boys) to a high of 35% (for girls) in the construction sector.

Africa has the greatest incidence of economically active children: 41% of children in the continent are at work.

On average, more than 30% of African children between 10 and 14 are agricultural workers.

In Rwanda, there are an estimated 400,000 child workers. Of these, 120,000 are thought to be involved in the worst forms of child labour and 60,000 are child domestic workers.

A recent survey by the Ministry of Public Service and Labour in Rwanda of children involved in prostitution in several large Rwandan cities found that 40% of child prostitutes had lost both of their parents, 94% lived in extreme poverty and 41% had never been to school.

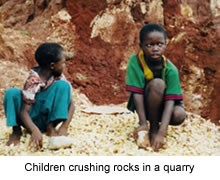

In Tanzania, some 4,600 children are estimated to be working in small-scale mining.

In Tanzania, children as young as eight years old dig 30 metres underground in mines for eight hours a day, without proper lighting and ventilation – constantly in danger of injury or death from cave-ins.

The Government of Kenya has recently reported that 1.9 million children between the ages of 5–17, are working children. Only 3.2% of these children have attained a secondary school education and 12.7% have no formal schooling at all.

During the peak coffee picking season in Kenya, it has been estimated that up to 30% of the pickers are younger than 15.

According to the Government of Zambia, there are some 595,000 child workers in Zambia. Of these, 58% are 14 or younger and, thus, ineligible for any form of employment under the Employment of Young Persons Act.

It has been estimated that as many as 5 million children in Zimbabwe between the ages of 5 and 17 years are being forced to work in Zimbabwe.

An International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) survey of children working in small scale mines in Madagascar showed that more than half (58%) were aged 12 or under, only a third had opportunities to learn skills and half came from families that were in a precarious economic situation with difficult living conditions.

Some 120,000 children under the age of 18 are thought to have been coerced into taking up arms as child soldiers, or becoming military porters, messengers, cooks or sex slaves in Africa.

Between 10,000 and 15,000 children from Mali are working on plantations in Côte d'Ivoire. Many of them are victims of child trafficking.

It is estimated that 50,000 children are working as domestics in Morocco.

In West Africa, an estimated 35,000 children are in commercial sexual exploitation.

Adapted from: Cornell University, Website

Reducing Child Labour in Tanzania through Education

In rural Tanzania, one out of three children between the ages of 10 and 14 work outside the family. They labor as farm workers, miners, domestic servants, and prostitutes, often under abusive and exploitive conditions.

Detrimental Working Conditions

Commercial agriculture in Tanzania employs large numbers of these youngsters. They provide much of the manual and machine-based labour on tobacco, coffee, tea, sugarcane, and sisal plantations. For example, in one area of the coastal region, 30 percent of the sisal plantation workers are children aged 12 to 14. They labour up to 11 hours per day with no specific rest periods, six days a week. Their wages are half that of adults, while nourishment and lodging are inadequate. Only half have completed primary school. Some plantations require as much as 14-, 16-, or even 17-hour work days. Mines and quarries also employ large numbers of youth who spend most of their days toiling above or below ground in very hazardous conditions. They risk injury from dust inhalation, blasting, mine collapse, flooding, as well as illness from silicosis.

Young girls are often lured away from their rural families with schemes that promise lucrative employment in towns and cities, only to be exploited as underpaid domestic servants that work as many as 16 or 18 hours per day. Domestic servitude in urban areas also make for an easy transition to child prostitution, which is a growing industry in Tanzania. As much as 25 percent of child prostitutes are former domestic servants.

Why Such Widespread Child Labor?

Poverty is one obvious reason for such widespread child labor in Tanzania. Over 50 percent of Tanzania's 36 million people live in extreme poverty, surviving on less than one US dollar per day. Many parents feel their survival is dependent on sending their children to work. Fortunately, income generation loan programs, also known as micro-credit disbursements, have had some success in giving families an economic boost.

Meanwhile, Tanzania's education system has drastically declined over the last 20 years due to funding cuts and teacher shortages. Currently, either no education is available or it is of such poor quality that it makes little sense for parents to send their children to school. Close to half the children are not enrolled, while the majority of those enrolled also work and are in constant danger of dropping out. If high quality education were made available, many more children would attend and fewer would enter the labor force. Education plays a critical role in combating child labor.

An Innovative Educational Strategy

To address this need for high-quality basic education, Education Development Center (EDC) and its partner, Research Triangle Institute (RTI), are key players in a program called Time-Bound Program on Eliminating Child Labor in Tanzania, which is funded by the US Department of Labor. EDC and RTI are establishing community learning centers in the 11 Tanzanian districts that have the highest incidence of child labor. 200 Interactive Radio Instruction (IRI) lessons for each of the first four grades will be developed in these centers. IRI is an innovative methodology that uses radio broadcasts that summon the participation of groups of listening students while their activities are facilitated by onsite teachers. The IRI curricula will include Swahili, mathematics, English, science, social studies, essential life skills, and navigating Tanzania's job market. International Labor Organization (ILO) and other NGOs are also identifying children who work, negotiating with employers, and bringing them to the community learning centers for their participation. When children complete the fourth grade, they will be assisted to integrate back into the formal school system or into a vocational program to prepare them for more stable, less dangerous work in the years ahead.

Adapted from: International Educational Systems, News, Website

Resource 3: My timeline